Abstract

Purpose

Exposure to end-of-life and chronic illness on a daily basis may put palliative healthcare professionals’ well-being at risk. Resilience may represent a protective factor against stressful and demanding challenges. Therefore, the aim is to systematically review the quantitative studies on resilience in healthcare professionals providing palliative care to adult patients.

Methods

A literature search on PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science and PsycINFO databases was performed. The review process has followed the international PRISMA statement guidelines.

Results

At the initial search, a total of 381 records were identified. Twelve articles were assessed for eligibility and, finally, 6 studies met all the inclusion criteria. Of these, four researches were observational and two interventional pilot studies. From the systematic synthesis, palliative care providers’ resilience revealed to be related to other psychological constructs, including secondary traumatic stress, vicarious posttraumatic growth, death anxiety, burnout, compassion satisfaction, hope and perspective taking.

Conclusions

The current systematic review reported informative data leading to consider resilience as a process modulator and facilitator among palliative care professionals. A model on palliative healthcare providers’ experience and the role of resilience was proposed. Further studies may lead to its validation and implementation in assessment and intervention contributing to foster palliative healthcare professionals’ well-being.

Keywords: Resilience, Palliative care, Burnout, End-of-life, Chronicity, Healthcare professionals

Introduction

The concept of resilience has significantly changed over the past two decades [1]. To date, there is no accepted universal definition. Originally, it was conceptualized as a trait, thus as a stable attribute determined by personality [2–5]. More recently, resilience has been considered as a result of multiple factors protecting individuals from the negative effects of stress and adversity [6]. This approach includes internal factors such as (epi)genetics, personal traits or beliefs [7–9] and external and environmental factors like social, material or energy resources [10]. Finally, resilience has been intended as a contextual and dynamic process of adaptation, considering temporal aspects like pre-adversity functioning and trajectories of post-adversity adjustment [11, 12].

As a result, over the years, researchers have approached the study of resilience from different perspectives. Aburn et al. [13] conducted an integrative review examining how resilience is defined in empirical research. According to the authors, resilience describes and explains the complexity of the responses—given by a person or a group—to traumatic and challenging circumstances [13]. However, further definitions were provided. On the one hand, several authors considered resilience as a process of overcoming adversity and rising above in front of crisis and trauma [14–17]. On the other hand, resilience was explained too as the ability to adjust or successfully adapt to challenging situations [18–20]. Moreover, some researchers referred to resilience as the result of personal strength originating from previous experiences and social support throughout a demanding and a stressful period [19, 21–24]. In addition, others considered good mental health as a ‘proxy’ for resilience [16, 25, 26]. Based on this definition, a resilient individual may present a stable trajectory of healthy functioning after adverse or traumatic events. Finally, resilience was described as the ability to ‘bounce back’ too. In other words, resilient individuals or groups may be able to recover from traumatic or difficult events jumping back to a baseline condition of health or well-being [27].

In a broad sense, resilience is therefore intended as the individual and group positive responses to adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats or any significant source of stress [28].

Research on resilience has focused on a variety of study populations and disciplinary areas so far, including healthcare settings [13]. Since health care may represent a stressful and demanding challenge, resilience has been recently recognised as a potential resource for healthcare professionals. Indeed, in a recent review, a strong correlation between resilience, high persistence, high-self-directedness and low avoidance of challenges was identified suggesting that resilience may represent a protective factor in terms of maintaining an adaptable and effective workforce [29]. Moreover, diverse studies considering healthcare professionals identified resilience as a positive attitude towards patient population, as well as a competence to be developed or strengthened [30–33]. Resilience was described as a personal resource, leading to positive adaptation [29] and a protecting factor against burnout [34]. Studies on healthcare professionals working in critical care units were conducted too, showing the mediating role of resilience between burnout conditions and health-related quality of life, buffering the impact of negative outcomes of work-related stress [35, 36].

Resilience may play an important role for palliative healthcare professionals, too. Working in such settings can put healthcare professionals’ well-being at risk, since exposure to death and dying, and legal and bioethical issues, as well as caring for patients with serious illness on a daily basis, may represent a challenge and a source of moral distress [37, 38], burnout [39] and impoverishment of professional quality of life [40].

Recently, a qualitative systematic review on palliative care nursing has been conducted [41]. However, as far as our knowledge, an overview of the quantitative studies on resilience in healthcare professionals providing palliative care and dealing with end-of-life among adult patients still lacks. Thus, the aim of the current research is to systematically review the studies concerning this issue.

Methods

A systematic review of the literature on resilience in healthcare professionals providing palliative care to adult patients was carried out. A prior search on registered and/or work in progress studies on this topic through the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) was conducted. The register provided no similar results. Thus, the systematic review protocol was recorded (ref. CRD42019126648).

The current research is part of a broader project called WeDistress HELL Project (WEllness and DISTRESS in HEalth care professionals dealing with end of Life and bioethicaL issues) approved by Ethical Committee of ICS Maugeri - Institute of Pavia (June 2018, Protocol No. 2211CE). PRISMA statement guidelines were followed [42].

Search strategy and data extraction

The primary search of literature was conducted on four public databases: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science and PsycINFO. Relevant articles were identified on 1 February 2019 by querying the following string: (resilience) AND (‘palliative care’), (resilience) AND (‘end of life’ OR ‘end-of-life’). A reference management and bibliography-creating software (EndNote Web) were included in the review process.

As for the data extraction, the eligibility of each record was independently assessed by the reviewers. Progressive exclusion was conducted starting from the title, then the abstract and finally the full text. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were discussed and accepted after full consensus.

Eligibility criteria

Researches to February 2019 concerning healthcare providers’ resilience related to adult palliative care were included. No date range restriction was considered. Studies focusing on patients and/or family/caregivers and/or healthcare professionals providing only paediatric palliative care were not considered. Limitations to document type were adopted: grey literature, editorials, case studies and theoretical and discussion papers, as well as reviews, were not taken in account. Only English research articles published on peer-reviewed journals were included. As for the methodology, only articles providing quantitative data were considered eligible to the current review.

Results

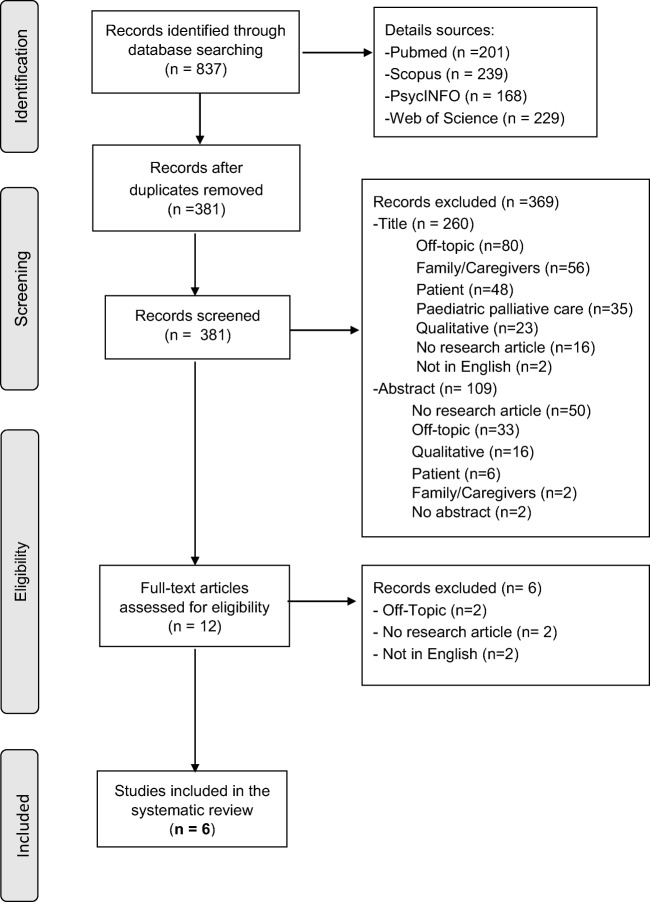

The database searches resulted in 837 titles. After removal of duplicates (n = 456), a total of 381 records were identified. Twelve articles were assessed for eligibility (369 studies excluded) and, finally, 6 studies met all the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of records identified, screened and included in the systematic review, according to PRISMA reporting guidelines

For each article included in the systematic review, different kinds of information were extracted, including country, study design, participants and measures as well as main results (Table 1). Each country was listed with the corresponding Human Development Index (HDI), which is a summary measure of average achievement in three key dimensions of human development: ‘long and healthy life’ (life expectance at birth), ‘knowledge’ (expected years of schooling and mean years of schooling) and ‘a decent standard of living’ (Gross National Income per capita) [43]. Three researches were conducted in the USA [44–46] and three in Europe (Spain, Poland and the UK) [47–49]. As for the design, two studies were cross-sectional and correlational [44, 47], two were interventional pilot studies [45, 46], one was a correlational study [49] and one conducted a tool development and validation [48]. Finally, as regards the participants, all studies included nurses. Of these, two included also physicians [45, 46] and three other healthcare professions, such as social workers, counsellors, consultants, mental health workers and occupational therapists [45, 46, 48]. All studies included healthcare professionals providing exclusively adult palliative care, with the exception of one study involving paediatric palliative care providers also [44].

Table 1.

Articles included in the systematic review

| Author (year) | Country (HDI*, ranking) | Study design | Subjects (N°, mean age ± SD, age range) | Measures | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edo-Gual et al. (2015) [47] | Spain (0.891, 26) | Cross-sectional and correlational study | Nursing students (N = 760, 22–44 ± 5.24) |

Collett-Lester Fear of Death Scale (CLFDS) Death anxiety Inventory-Revised (DAI-R) Brief Resilient Coping Scale (BRCS) Trait Meta-Mood Scale (TMMS-24) Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) |

Death anxiety showed a negative significant correlation with resilience (r = − 0.22; p < .01). Through stepwise multiple linear regression analysis, attention to feelings, resilience and self-esteem are significant predictors (R2adj = 0.15). |

| Klein et al. (2017) [46] | USA (0.924, 13) | Exploratory, pre-post, interventional pilot study | Nurses, physicians and counsellors/social workers (N = 17, > 20) |

A copyrighted resiliency development program Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL5) |

At 6 months following the completion of the educational program, only 8 participants completed all surveys. Post-intervention data showed an increase of compassion satisfaction (CS; 1.12, p = 0.67), a decrease of burnout (BO; − 0.63, p = 0.50) and a minimal change in secondary traumatic stress (STS; − 0.13, p = 0.96). |

| Oginska-Bulik (2018) [49] | Poland (0.865, 33) | Correlational study | Nurses (N = 72, 46.01 ± 10.69, 22–72) |

Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale (STSS) Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) Resiliency Assessment Scale (SPP-25) |

Results showed a negative relationship between resilience and secondary traumatic stress (STS; r = − 0.36, p < 0.01) and a positive relationship with vicarious posttraumatic growth (VPTG; r = 0.50, p < 0.001). Regression analysis showed resilience to be a predictive factor of STS and VPTG. STS and VPTG correlated negatively (r = − 0.27, p < 0.05) |

| Mehta et al. (2016) [45] | USA (0.924, 13) | Interventional pilot study | Physicians, nurses practitioners, nurses and social workers (N = 16, 44 ± 8.1) |

Relaxation Response Resiliency Program for Palliative care Clinicians (3RP-PCC) Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) Positive and Negative Affects Schedule (PANAS) Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R) Brief Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) General Self-Efficacy scale (GSE) |

Following the 3RP-PCC intervention, participants showed significant reduction in perceived stress (z = − 2.17, p = 0.03; d = 0.65) and increase in perspective taking (z = − 1.66, p = 0.10; d = 0.67). |

| Pangallo et al. (2016) [48] | United Kingdom (0.922, 14) | Tool development and validation | Nurses, consultants, social workers, mental health workers, occupational therapists (N = 284, 45.53 ± 9.35, 18–54) |

Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire (MO AQ) Single-Item Measures of Personality (SIMP) Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-10) Ego-Resiliency-89 scale (ER-89) Psychological Capital (PsyCap) Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) World Health Organization Well-Being Index (WHO-5) |

Situation Judgement Test (SJT) provided acceptable test-retest scores (0.71, p = <0.001) and high internal consistency (α = 0.91). It was positively correlated with resilience self-report measures: PsyCap (r = 0.51, p < 0.001); CD-10 (r = 0.35, p < 0.001); BRS (r = 0.34, p < 0.001) and ER-89 (r = 0.37, p < 0.001). |

| Rushton et al. (2015) [44] | USA (0.924, 13) | Cross-sectional survey | Nurses (N = 114, 32, 22–67) |

Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) Moral Distress Scale (MDS) Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) Meaning Scale State Hope Scale |

Resilience revealed to be a protective factor against emotional exhaustion (r = − 0.31, p < 0.01) contributing to personal accomplishment (r = 0.59, p < 0.01). Higher scores of resilience were associated with high level of hope (r = 0.51, p < 0.01) and low level of stress (r = − 0.44, p < 0.01) |

*Human Development Index (HDI): a composite index measuring average achievement in three basic dimensions of human development: a long healthy life, knowledge and a decent standard of living

The quantitative data provided in the six studies described the relationship between palliative care professionals’ resilience and other constructs such as the following: secondary traumatic stress, vicarious posttraumatic growth, death anxiety, burnout, compassion satisfaction, hope and perspective taking.

Resilience, death anxiety and traumatic experiences

Edo-Gual et al. [47] showed that death anxiety was negatively correlated with resilience (r = − 0.22, p < 0.1). Moreover, a stepwise multiple linear regression analysis indicated that resilience and attention to feelings and self-esteem were significant predictors of death anxiety (R2adj = 0.15, p < 0.01). This suggested that social and emotional competencies associated with positive coping may modulate fear of death.

Moreover, resilience revealed to be negatively correlated with secondary traumatic stress (r = − 0.36, p < 0.01) and openness to new experiences and sense of humour resulted as the main predictive resilience factor of secondary traumatic stress symptoms, including intrusion (ß = − 0.47, R2 = 0.09), avoidance (ß = − 0.35, R2 = 0.25) and arousal (ß = − 0.41, R2 = 0.22) [49]. In addition, after completion of a resiliency development program, secondary traumatic stress scores minimally changed (− 0.13, p = 0.96) [46].

Nevertheless, experiencing secondary traumatic stress may lead to positive changes, to the so-called vicarious posttraumatic growth. Indeed, Oginska-Bulik et al. [49] showed that resilience was positively correlated with vicarious posttraumatic growth (r = 0.50, p < 0.001) and regression analysis showed two resilience factors (i.e. openness to new experiences and sense of humour, ß = − 0.46, p < 0.01; personal competencies and tolerance of negative emotions, ß = 0.34, p < 0.05) to be significant predictors of vicarious posttraumatic growth.

Resilience, stress and burnout

According to Rushton et al. [44], resilience may help individuals to reduce burnout: resilience is revealed to be a protective factor against emotional exhaustion (r = − 0.31, p < 0.01) contributing to personal accomplishment (r = 0.59, p < 0.01). Moreover, higher scores of resilience were associated to low levels of perceived stress (r = − 0.44, p < 0.01) and with high levels of hope (r = 0.51, p < 0.01).

Resilience in assessment and interventions

Pangallo et al. [48] developed and validated within palliative care context the Situational Judgement Test (SJT). The tool aimed to measure behaviours associated with resilience among palliative care providers. Results provided acceptable test-retest scores (0.71, p < 0.001) and high internal consistency (α = 0.91). Situational judgement was positively correlated with self-report measures of resilience.

Two interventional studies were included in the systematic synthesis [45, 46]. Klein et al. [46] proposed a copyrighted resiliency development program. At 6 months following the completion, post-intervention data were collected. Resilience influenced the change in the survey scores, increasing compassion satisfaction (1.12, p = 0.67) and decreasing burnout (− 0.63, p = 0.50). Some limits of the studies, as described by the researchers too, are the small sample size, being pilots and the absence of a control group. Mehta et al. [45] implemented the Relaxation Response Resiliency Program for Palliative care Clinicians (3RP-PCC). Following the intervention, participants showed significant reduction in perceived stress (z = − 2.17, p = 0.03; d = 0.65) and increase in perspective taking (z = − 1.66, p = 0.10; d = 0.67).

Discussion

The studies included in the systematic synthesis reported informative quantitative data concerning palliative care professionals’ resilience. Three researches showed resilience to be significantly correlated to different constructs, including death anxiety, secondary traumatic stress, vicarious posttraumatic growth, burnout, stress, attention to feelings, self-esteem and hope [44, 45, 49]; two studies proposed specific interventions on resilience reporting informative changes in burnout, secondary traumatic stress, stress, compassion satisfaction and perspective taking [45, 46]; and one study conducted the development and validation of a test measuring resilience in palliative care workers [48].

Palliative care professionals are exposed to death and dying on a daily basis. Their attitude toward death may influence their well-being as well as the quality of care they offer to terminally ill patients and their families [50]. Edo-Gual et al. [47] showed that higher scores on resilience indicated lower levels of death anxiety. As a result, fostering resilience among palliative care professionals may help them to manage experiences of loss and grieve exposure. Moreover, the contact with such touching experiences potentially represents an opportunity to grow as individuals.

Exposure to death and being constantly in contact with people who directly experienced trauma or suffering may lead healthcare professionals to develop secondary traumatic stress [51]. However, some positive changes resulting from secondary traumatic stress may occur in the individual’s psychological functioning, including self-perception, interpersonal relationship and philosophy of life [52]. This effect is known as vicarious posttraumatic growth. In this scenario, resilience represents an important protective factor against secondary trauma avoiding the development of secondary traumatic stress as well as promoting positive changes [49].

Absenteeism, increased medical errors, poor communication and teamwork are some of the negative effects of stress exposure among palliative care professionals [53]. High levels of stress may lead providers to experience burnout [44]. That includes emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and reduced personal accomplishment [54]. In particular, emotional exhaustion revealed to be the main predictor, as it is considered the first step in burnout [55]. Rushton et al. [44] showed a strong association among resilience, hope and burnout. In particular, resilience as well as hope supported the development of strategies aimed to reduce vulnerability to emotional exhaustion contributing to personal accomplishment. This suggested that both constructs may contribute to increase work satisfaction among healthcare professionals.

To date, little research has been conducted toward resilience assessment among palliative care professionals [48]. The validation of the Situational Judgement Test (SJT) represented an attempt to develop a specific questionnaire tailored to palliative care workers. The scale revealed to be a reliable and valid measure. As to the practical implications, its implementation in multidisciplinary teams and using a reflective learning approach may represent for the healthcare professional an opportunity to debrief about the emotional impact of job-related adversities and to reach peer support [48].

The interest on treatments aimed to promote providers’ wellness and resilience has increased, too [45]. The two interventional studies, included in this systematic review, were pilot, had a small sample size and involved no control group. Nevertheless, both reported informative data on resilience following the completion of an educational program [45, 46]. Mehta et al. [45] implemented a program based on the principles of cognitive behavioural therapy and positive psychology. In fact, the intervention aimed to evoke a relaxation response through breath awareness exercises, to reduce overall stress reactivity and to increase connection with others. The intervention led participants to a reduction in perceived stress and an increase in perspective taking. Klein et al. [46] proposed an intervention consisting of sessions aimed to educate participants about compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, vicarious trauma, self-care, resilience and quality of life completing self-assessments and participating to group discussions. Post-intervention data showed in all participants an increase of compassion satisfaction and a decrease of burnout. In summary, the two interventional studies suggest that resiliency development programs based on cognitive stimulation and/or social support may lead palliative care professionals to gain self-awareness fostering their well-being.

Resilience as a process modulator and facilitator

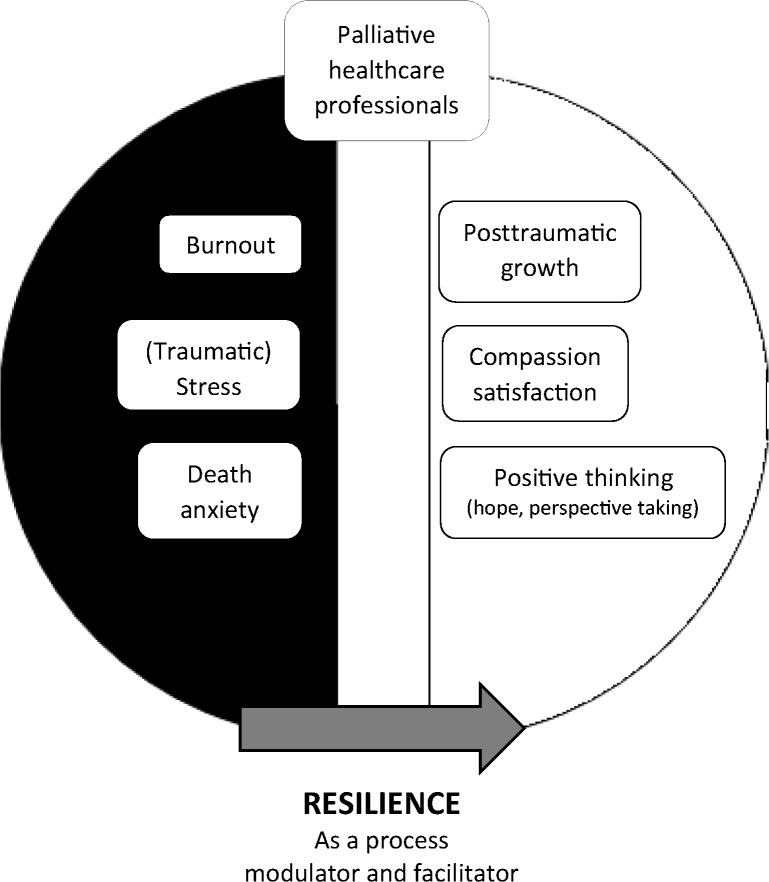

A recent qualitative systematic review focusing on resilience in palliative care inpatient nursing workforce identified exposure to death, stress and coping as informative subthemes [41]. According to the emerged results, resilience occurs when adversity and stressful experiences lead nurses to adapt through a meaning construction process. Therefore, the cognitive ability to give meaning and shape to stress appears to determine resilience development or maintenance. Similarly, in the current systematic review, resilience appeared to be an influencing construct in palliative care professionals’ well-being. In particular, it seems to modulate death anxiety, traumatic experiences, stress and burnout predicting vicarious posttraumatic growth, compassion satisfaction, hope and increased perspective taking. As a result, while in the model of Powel et al. [41] resilience may be seen as originating from adverse experiences and the result of abilities aimed to overcome challenging situations, in the present model we propose, resilience could be considered as a process modulator and facilitator that may help palliative care professionals to reach positive adaptation (Fig. 2). Summing up, both two models focus on healthcare professionals’ well-being within a context where end-of-life and chronicity reveal to be influencing aspects. Specifically, stressful experiences, trauma, exposure to death and growth appear to be common aspects included in the systematic synthesis. As for the differences, while Powel et al.’s [41] model adopted a qualitative approach and considered coping and meaning construction, the current research adopted a quantitative approach identifying burnout, compassion satisfaction and positive thinking (i.e. hope, perspective taking) as factors to be included in the data analysis. Thus, the two models may be integrated in order to orient future researches to develop a mixed-methods model explaining resilience in this population, as well as to promote resilience as a factor in support of palliative care professionals’ personal growth.

Fig. 2.

Palliative care providers’ experience and the role of resilience

Limitations and strengths

The current systematic review presents some limits. First, the included studies were exclusively conducted in the USA or in European countries. Thus, data on resilience in palliative care professionals belonging to other cultures (e.g. Asian or African) were not provided. Second, the interventional studies included in the analysis, as described by the researchers too, were pilot, had a small sample size and involved no control group.

However, it is noteworthy that the analysed data were recent, as the included studies range from 2015 to 2018. Moreover, to the best of the author’s knowledge, this is the first quantitative systematic review addressing resilience in healthcare professionals providing adult palliative care.

Future directions and clinical implications

The results allowed the authors to develop a model concerning the role of resilience in palliative care providers’ personal and professional growth. Further studies to validate this proposed framework should be conducted considering wider sample sizes and the presence of a control group. In addition, further correlational and regressional studies aimed to examine in depth the predictive role of resilience on positive constructs like self-esteem and attention to feelings [47], posttraumatic growth [49], compassion satisfaction [46] and hope [44] are recommended. Also, interventional studies on this topic should take into account specific cognitive and behavioural stimulation exercises [45], social support and educational sessions on themes connected to psychological well-being in work setting, as main strategies to enhance resilience [46].

Conclusion

Since resilience has no accepted universal definition, it remains a construct difficult to quantify. Nevertheless, the current systematic review reported informative data leading to consider resilience as a process modulator and facilitator among palliative care professionals. From the analysis of the included studies, particular attention on research concerning palliative care providers’ resilience should be taken into account, as working in contact with end-of-life and chronic illness on a daily basis may put their well-being at risk. The validation of the proposed model on the role of resilience may lead to its implementation in assessment and intervention contributing to foster palliative care professionals’ well-being.

Contributors

FZ completed the electronic search. FZ, MM and AG performed the screening. All authors read the included articles, took part in data synthesis, model conceptualization and draft writing.

Funding information

This work was partially supported by ‘Ricerca Corrente’ funding scheme of the Ministry of Health, Italy.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned; externally peer-reviewed.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Chmitorz A, Kunzler A, Helmreich I, Tuscher O, Kalisch R, Kubiak T, et al. Intervention studies to foster resilience - a systematic review and proposal for a resilience framework in future intervention studies. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;59:78–100. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Block JH, Block J (1980) The role of ego-control and ego-resiliency in the organization of behavior. In: W A Collins (Ed) The Minnesota symposia on child psychology: development of cognition, affect, and social relations, Vol 13, pp 39–101

- 3.Connor KM, Davidson JR, Lee LC. Spirituality, resilience, and anger in survivors of violent trauma: a community survey. J Trauma Stress. 2003;16:487–494. doi: 10.1023/A:1025762512279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ong AD, Bergeman CS, Bisconti TL, Wallace KA. Psychological resilience, positive emotions, and successful adaptation to stress in later life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;91:730–749. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu T, Zhang D, Wang J. A meta-analysis of the trait resilience and mental health. Personal Individ Differ. 2015;76:18–27. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fletcher D, Sarkar M. Psychological resilience: a review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. Eur Psychol. 2013;18:12–23. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reivich K, Shatté A. The resilience factor: 7 essential skills for overcoming life’s inevitable obstacles. New York: Broadway Books; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Southwick SM, Litz BT, Charney D, Friedman MJ. Resilience and mental health: challenges across the lifespan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Southwick SM, Charney DS. Resilience: the science of mastering life’s greatest challenges. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hobfoll SE, Stevens NR, Zalta AK. Expanding the science of resilience: conserving resources in the aid of adaptation. Psychol Inq. 2015;26:174–180. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2015.1002377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonanno GA, Diminich ED. Annual research review: positive adjustment to adversity--trajectories of minimal-impact resilience and emergent resilience. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;54:378–401. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonanno GA, Romero SA, Klein SI. The temporal elements of psychological resilience: an integrative framework for the study of individuals, families, and communities. Psychol Inq. 2015;26:139–169. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aburn G, Gott M, Hoare K. What is resilience? An integrative review of the empirical literature. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72:980–1000. doi: 10.1111/jan.12888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) Depress Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonanno GA. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? Am Psychol. 2004;59(1):20–28. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kralik D, van Loon A, Visentin K. Resilience in the chronic illness experience. Educ Action Res. 2006;14(2):187–201. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ungar M. Resilience across cultures. Br J Soc Work. 2008;38:218–235. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Easterbrooks MA, Drisoll JR, Barlett JD. Resilience in infancy: relational approach. Res Hum Dev. 2008;5(3):139–152. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montepetit MA, Bergeman CS, Deoboeck PR, Tiberio SS, Boker SM. Resilience-as-process: negative affect, stress and coupled dynamical systems. Psychol Aging. 2010;25(3):631–640. doi: 10.1037/a0019268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wingo AP, Fani N, Bradley B, Ressler KJ. Psychological resilience and neurocognitive performance in a traumatized community sample. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27(8):768–774. doi: 10.1002/da.20675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dowrick C, Kokanovic R, Hegarty K, Griffith F, Gunn J. Resilience and depression: perspectives from primary care. Health (London) 2008;12(4):439–452. doi: 10.1177/1363459308094419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canvin K, Marttila A, Burstrom B, Whitehead M. Tales of the unexpected? Hidden resilience in poor households in Britain. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(2):238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Theron LC, Malindi MJ. Resilient street youth: a qualitative South African study. J Youth Stud. 2010;13(6):717–736. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janssen BM, Van Regenmortel T, Abma TA. Identifying sources of strength: resilience from the perspective older people receiving long-term community care. Eur J Ageing. 2011;8(3):145–156. doi: 10.1007/s10433-011-0190-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burns RA, Anstey KJ. The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): testing the invariance of a uni-dimensional resilience measure that is independent of positive and negative affect. Personal Individ Differ. 2010;48(5):527–531. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Southwick SM, Bonanno GA, Masten AS, Panter-Brick C, Yehuda R. Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: interdisciplinary perspectives. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2014;5(1):25338. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v5.25338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Edward KL, Welch A, Chater K. The phenomenon of resilience as described by adults who have experienced mental illness. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(3):587–595. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Psychological Association . The road to resilience: American Psychological Association. DC: Washington; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robertson HD, Elliott AM, Burton C, Iversen L, Murchie P, Porteous T, et al. Resilience of primary healthcare professionals: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66:e423–e433. doi: 10.3399/bjgp16X685261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jackson D, Firtko A, Edenborough M. Personal resilience as a strategy for surviving and thriving in the face of workplace adversity: a literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2007;60:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stevenson AD, Phillips CB, Anderson KJ. Resilience among doctors who work in challenging areas: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61:e404–e410. doi: 10.3399/bjgp11X583182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zwack J, Schweitzer J. If every fifth physician is affected by burnout, what about the other four? Resilience strategies of experienced physicians. Acad Med. 2013;88:382–389. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318281696b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooke GP, Doust JA, Steele MC. A survey of resilience, burnout, and tolerance of uncertainty in Australian general practice registrars. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keeton K, Fenner DE, Johnson TR, Hayward RA. Predictors of physician career satisfaction, work-life balance, and burnout. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:949–955. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000258299.45979.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arrogante O, Aparicio-Zaldivar E. Burnout and health among critical care professionals: the mediational role of resilience. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2017;42:110–115. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colville GA, Smith JG, Brierley J, Citron K, Nguru NM, Shaunak PD, Tam O, Perkins-Porras L. Coping with staff burnout and work-related posttraumatic stress in intensive care. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2017;18(7):e267–e273. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maffoni M, Argentero P, Giorgi I, Hynes J, Giardini A (2019) Healthcare professionals’ moral distress in adult palliative care: a systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Maffoni M, Argentero P, Giorgi I, Giardini A (2019) Healthcare professionals’ perceptions about the Italian law on advance directives. Nurs Ethics. 10.1177/0969733019878831 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Hynes J, Maffoni M, Argentero P, Giorgi I, Giardini A. Palliative medicine physicians: doomed to burn? BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2019;9:45–46. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2018-001731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Samson T, Shvartzman P. Association between level of exposure to death and dying and professional quality of life among palliative care workers. Palliat Support Care. 2018;16:442–451. doi: 10.1017/S1478951517000487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Powell MJ, Froggatt K, Giga S (2019) Resilience in inpatient palliative care nursing: a qualitative systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Human Development Report (2016) Human Development Index and its components. http:// hdr. undp. org/ en/composite/ HDI. Accessed 18 Mar 2019

- 44.Rushton CH, Batcheller J, Schroeder K, Donohue P. Burnout and resilience among nurses practicing in high-intensity settings. Am J Crit Care. 2015;24:412–420. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2015291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mehta DH, Perez GK, Traeger L, Park ER, Goldman RE, Haime V, et al. Building resiliency in a palliative care team: a pilot study. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2016;51:604–608. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klein CJ, Riggenbach-Hays JJ, Sollenberger LM, Harney DM, McGarvey JS. Quality of life and compassion satisfaction in clinicians: a pilot intervention study for reducing compassion fatigue. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35:882–888. doi: 10.1177/1049909117740848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Edo-Gual M, Monforte-Royo C, Aradilla-Herrero A, Tomas-Sabado J. Death attitudes and positive coping in Spanish nursing undergraduates: a cross-sectional and correlational study. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24:2429–2438. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pangallo A, Zibarras L, Patterson F. Measuring resilience in palliative care workers using the situational judgement test methodology. Med Educ. 2016;50:1131–1142. doi: 10.1111/medu.13072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oginska-Bulik N. Secondary traumatic stress and vicarious posttraumatic growth in nurses working in palliative care - the role of psychological resilience. Advances in Psychiatry and Neurology. 2018;27:196–210. [Google Scholar]

- 50.de Araújo MMT, da Silva MJP, Francisco MCPB. Nursing the dying: essential elements in the care of terminally ill patients. Int Nurs Rev. 2004;51:149–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2004.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bride BE, Robinson MM, Yegidis B, Figley CR. Development and validation of the secondary traumatic stress scale. Res Soc Work Pract. 2004;14:27–35. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Manning-Jones S, de Terte I, Stephens C. The relationship between vicarious posttraumatic growth and secondary traumatic stress among health professionals. J Loss Trauma. 2017;22:256–270. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kamal AH, Bull J, Kavalieratos D, Taylor DH, Jr, Downey W, Abernethy AP. Palliative care needs of patients with cancer living in the community. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7:382–388. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach burnout inventory manual. 4. Menlo Park: Mind Garden Inc; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cordes CL, Dougherty TW. A review and an integration of research on job burnout. Acad Manag Rev. 1993;18:621–656. [Google Scholar]