Abstract

Background:

Long-term treatments of herpes simplex with drugs such as acyclovir, the side effects to such drugs including limited usage during the lactation period, and concerns for the emergence of drug-resistant strains have given rise to a need for new medications with fewer complications. Nowadays, there is an increasing usage of herbal medicines throughout the world due to their higher effectiveness and safety. The present study aims to assess the effects of hydroalcoholic cinnamon extract on herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) in culture with vero cells.

Materials and Methods:

In this in vitro study Hydroalcoholic extract of cinnamon was extracted through percolation. To assess cell survival rates, the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay was employed, and the tissue culture infective dose 50 assay was used to quantify the virus. Effects of the extract were evaluated in three stages, including before, during, and after viral inoculation into the culture medium. Two-way ANOVA and Post hoc analysis the test was performed in 1, 0.5, and 0.25 mg/ml concentrations of cinnamon extract in every stage (P < 0.05).

Results:

Over 50% of the cells survived in the 0.25 mg/ml extract concentration. Results of our viral quantification showed a viral load of 105. The cinnamon extract was able to reduce the viral titer in all concentrations under study.

Conclusion:

Hydroalcoholic extract of cinnamon was effective in reducing the viral titer of HSV-1. This effect could have been caused by prevention of viral attachment to cells; however, further research is required to determine the exact mechanisms at play.

Key Words: Antiviral agents, cinnamomum zeylanicum, herpes virus 1

INTRODUCTION

Infections caused by herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) are among the most common types of infection in human populations, and production of antibodies cannot eliminate the virus.[1] Thus, the virus stays hidden in the sensory ganglia of the host, and the individual becomes a lifelong carrier.[2] Considering the intracellular replication of viruses, a proper antiviral compound should differentiate between the activities of the virus and the host with high specificity to minimize the damages to host cells. Vidarabine, iododeoxyuridine, and acyclovir are a few examples of drugs that prevent viral DNA synthesis.[3,4]

In this regard, acyclovir is usually the drug of choice for treatment of damages caused by HSV-1; this drug can only shorten the disease duration by preventing virus replication.[5,6] Lately, there has been an increasing interest in replacement of chemical drugs with herbal medicine due to drug resistance and the side-effects of chemical medications, especially the limitations on their use during the lactation period.[7,8] Of course, use of herbal medicines dates back to some years ago; the effect of various extracts was studied on HSV-1, including cinnamon.[9,10,11,12,13] In their overview in 2009, Reichling et al. studied the effects of essential oils extracted from different aromatic plants on HSV-1; they concluded that the essential oil of cinnamon can influence enveloped viruses based on a study on HSV-2.[14,15]

On the other hand, Benencia and Courrèges demonstrated that treatment with eugenol, a component of the bark of cinnamon, could significantly delay the corneal infection caused by HSV-1 in infected mice.[16] In Ooi et al.'s study in 2006 on the Chinese herbal medicine – cinnamomum cassia (Chinese cinnamon), it was reported that the oil extracted from one class of this species would contain 60% cinnamaldehyde; this research was the first one to firmly attribute the antimicrobial effects of this type of cinnamon to the cinnamaldehyde compound.[17] In 2012, Ojagh et al. announced that the bark of cinnamon contains 21 chemical compounds, which comprise 60.41% cinnamaldehyde and 3.19% eugenol and have an antibacterial effect on 5 types of food spoilage bacteria.[18]

Meanwhile, in a systematic review on the antibacterial, antifungal, antiparasitic, and antiadenoviral effects of cinnamon in vivo and in vitro, many benefits were attributed to cinnamon, including anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial effects, wound healing, and reduction of cardiovascular diseases and colon cancer.[19] Furthermore, Fani and Kohanteb recommended the use of cinnamon oil in toothpaste, mouthwash, chewing gum, or food preservatives to inhibit the growth of bacteria, fungi, and yeast cells.[20]

An overview of existing literature in the field reveals a scarcity of studies discussing the influence of cinnamon extract on HSV-1. Therefore, the authors decided to design the current study aiming to assess the in vitro effects of hydroalcoholic cinnamon extract on HSV-1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this experimental in vitro study, a sample of HSV-1 was acquired from the Virology Department of the Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. The virus is obtained from the canker sores of patients; the presence of the virus was confirmed by culture, polymerase chain reaction, and neutralization using guinea pig anti-HSV-1 serum (NIH, USA) and monoclonal (D and G) anti-HSV-1 antibodies. Virus titration was determined by quantal assay (tissue culture infective dose [TCID50]). TCID was calculated by Karber method.[21] Viral source was kept in the freezer at −70°C. In this research, vero cells were grown in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 IU/ml of penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. The vero cells had a concentration of 104 cells/ml.

After procuring a wood sample from a cinnamon tree, it was evaluated in terms of type and species in the laboratory of traditional medicine at the School of Pharmacy, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences; the sample was then registered under the code no. PM983 (voucher number) and the scientific name “Cinnamomumverum J. Presllauracese.” Using the cinnamon powder, the plant's hydroalcoholic extract was prepared in the medicinal chemistry laboratory of the Pharmacology Department at the Shiraz University of Medical Sciences through percolation (extraction under pressure). To dilute the hydroalcoholic extract, we used DMEM containing antibiotics. As there was the possibility of the extract being contaminated, 0.22 μm filters were used for sterilization purposes. The cinnamon extract was then kept in sterile glasses at 4°C to be used for testing.

The 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay was used to determine the cytotoxicity threshold of the extract. The cells were cultured in 96-well plates for 24 h. Then, the DMEM medium was removed and replaced with another DMEM containing different concentrations of the cinnamon extract (10, 5, 2.5, 1.25, 0.6, and 0.3 mg/ml); the cells were then incubated for 48 h at 37°C. After that, 5 mg/ml MTT solution and 5 μL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (1X) were added to each well, and after 2 h of incubation at 37°C, 50 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide was added to every well so that the formazan crystals formed due to reaction between MTT and the mitochondrial enzymes of living cells would dissolve; immediately after that, the solution's optical density (OD) was measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay microplate reader in the wavelength range of 410–630 nm. The well that in the highest concentration of the extract had a similar OD to that of the cell control well was considered the cytotoxicity threshold.[22]

In the next phase, after the vero cells were grown for 48 h at 37°C in an incubator containing 5% Co2, the DMEM medium was removed and washed twice with PBS. Then, 3 experimental groups were designed for different stages as follows: (1) Inoculation of the cinnamon extract 2 h before inoculation of HSV-1 into the cell culture medium: in this stage, 100 μL of the medium containing various cinnamon extract concentrations (1, 0.5, and 0.25 mg/ml) was added, and after 2 h, the medium containing different concentrations was evacuated and washed twice with PBS; next, 100 μL of the viral medium was added (multiplicity of infection [MOI] = 0.1). (2) Simultaneous inoculation of both the cinnamon extract and the virus into the cell culture medium: in this stage, 100 μL of the medium containing the virus (MOI = 0.1) was mixed with 100 μL of different concentrations of the extract (1, 0.5, and 0.25) and kept at 4°C for an hour; the mixtures were then added to the culture medium. (3) Inoculation of the cinnamon extract 2 h after inoculation of the virus into the cell culture medium: in this stage, the medium containing virus was added and then evacuated after 2 h, cells were washed twice with PBS, and finally, 100 μL of different concentrations of the extract (1, 0.5, and 0.25) was added.

In each stage, the plates were kept in an incubator containing 5% CO2for 48–72 h at 37°C and evaluated daily in terms of cytopathic effect (CPE) using an optical microscope. Then, the medium was removed from the cells to determine the viral titer (TCID50).

All testing stages were repeated three times to reduce statistical errors, and the averages were recorded as the final results. Note that a virus control group (containing cells + culture medium + TCID50) and a cell control group (containing cells + culture medium) existed in all three stages previously described.

SPSS statistics 16.0 for windows, SPSS Inc, (Chicago, IL, USA) was used for the purposes of data analysis. Significance level was set at P < 0.05 in all cases. To compare the effects of different concentrations, as well as the different stages of extract inoculation, we made use of the two-way ANOVA and Post hoc analysis (Duncan, Tukey).

RESULTS

Results of the MTT assay revealed that the cinnamon extract had a viral cell survival rate of over 50%, starting from the 1 mg/ml concentration approximately, and an OD close to that of the control group; in this study, concentrations of the stock solution was 1 mg/ml. A viral load of 105 was obtained in this study for the herpes virus cultured in vero cells.

Using the TCID50 assay to assess viral titer in the 3 aforementioned stages, the following results were acquired:

Two hours prior of viral inoculation

The cinnamon extract was able to reduce viral titer in all concentrations. Averagely speaking, the experimental groups had lower viral titers than the control group, which had a titer equaling Log105.166. Moreover, statistically significant differences existed between different concentrations (P < 0.05); in this regard, viral titer increased for any decrease in the extract concentration.

Simultaneous to viral inoculation

In this stage, the cinnamon extract could cause a significant reduction in viral titer in all concentrations. Even though viral titer was dependent on the extract concentration (inverse relationship), there were no statistically significant differences between different concentrations of the cinnamon extract.

Two hours after viral inoculation

This stage as well showed that the cinnamon extract had reduced titer of the herpes virus in all concentrations compared to the control group with a viral titer of Log105.166. Significant differences were observed between different extract concentrations (P < 0.05).

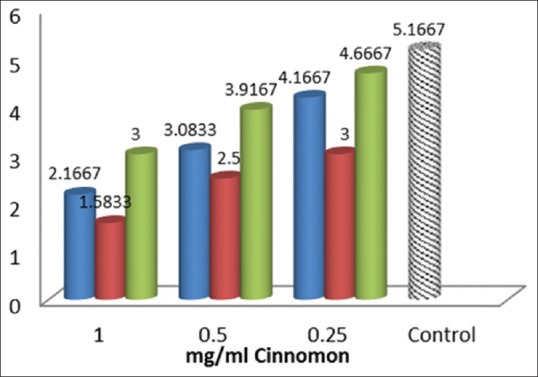

Figure 1 showed the viral titer before, during, and after viral inoculation into culture medium in different cinnamon extract concentrations.

Figure 1.

Comparison of viral titer before, during, and after viral inoculation into culture medium in different cinnamon extracts concentrations.  Mean viral titer by adding the cinnamon extract before inoculation of the virus.

Mean viral titer by adding the cinnamon extract before inoculation of the virus.  Mean viral titer by adding the cinnamon extract simultaneous to viral inoculation.

Mean viral titer by adding the cinnamon extract simultaneous to viral inoculation.  Mean viral titer by adding the cinnamon extract after viral inoculation.

Mean viral titer by adding the cinnamon extract after viral inoculation.

Our statistical tests revealed statistically significant differences between the 3 testing stages (P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

Discovering new drugs for treatment of herpes infections is important due to the existence of viral resistance in some HSVs. Although acyclovir is the drug of choice in treatment of wounds caused by herpes simplex, it can only provide its maximum antiviral effects within the initial 72 h after appearance of clinical symptoms. Acyclovir's topical cream is only effective when applied at the beginning of the latency period and appearance of signs. Moreover, the existing side effects to the drug has steered the general interest toward new medications with fewer complications. Meanwhile, due to their effectiveness and safety, herbal medicines have been a special point of focus in this regard.[13] Although effects of many plants have been specifically assessed on HSV type 1, our review of literature did not show any studies discussing the influence of hydroalcoholic cinnamon extract on this virus. In this regard, our research demonstrated the effectiveness of this extract in reducing the titer of HSV-1 in the culture medium.

The hydroalcoholic extract of cinnamon caused a significant decrease in viral titer of HSV-1 in the cell culture medium. In 2009, Monavari et al. studied the antiviral effect of licorice extract on herpes virus; however, they did not specify the type of licorice extract used in their study;[23] moreover, Ghaemi et al. evaluated the effect of the alcoholic extract of Echinacea purpurea (aerial part) on HSV-1 in 2007.[24] The present study used a hydroalcoholic extract; therefore, we were able to assess the effects of all cinnamon compounds soluble in either water or alcohol.

Similar to the study by Zehtabian and Shahrabadi (2008) on the antiviral effect of marjoram extract on herpes virus, we employed percolation to obtain the cinnamon extract.[25] The current study used the MTT assay to determine the non-cytotoxic concentrations of the extract; meanwhile, previous studies had used methods such as the Trypan blue exclusion test and vital staining with neutral red for this purpose.[13,23,25]

Some studies have evaluated the antiviral effects of plant extracts at different points in time because the first viral polypeptides or alpha polypeptides involved in reduction of cell protein synthesis appear in different intervals.[25] Some other studies were conducted in two stages – before and after viral inoculation;[12] however, since the objective of the research team in this study was to specify the effect of cinnamon based on time of viral inoculation, we designed our tests for three stages, including before, during, and after inoculation of herpes virus into the cell culture medium. Motamedifar et al. as well studied the effect of olive leaf extract in three stages – before, during, and 1 h after viral inoculation.[12]

In the studies on botany extracts of marjoram and the aerial part of Echinacea purpurea,[24,25] antiviral effects were witnessed in the pre-infection (cell contamination) stage, which is consistent with the findings of this research.

Since the present study as well shows a significant reducing effect on viral titer in all stages, especially the simultaneous inoculation stage, hydroalcoholic cinnamon extract might have similar inhibiting effects on attachment of HSV-1 onto host cells. Furthermore, this effect of cinnamon extract could have been caused by blocking the viral surface ligands responsible for attachment to cell surface receptors; another explanation would be the effect of the extract on the outermost layer of the virus and changes in the viral envelope layer, which would prevent viral attachment and thereby contamination of cells. Further research is required to determine the exact mechanisms involved in this particular effect.

On the other hand, in one study where the extract of 25 plants had an inhibiting effect on herpes simplex virus and reduced the CPE, the extract was stated to have had its best effect after viral adsorption onto cells.[26] Monavari et al.'s study as well reported the highest impact of licorice on HSV-1 within the 1st h following viral adsorption. These two studies provided inconsistent results with the results obtained in this study, which could be due to the different extract types or methods of extraction, aside from the differences in inhibition mechanisms.[23,25]

According to the statistical tests performed in this study, there were not any significant differences between different concentrations in the simultaneous inoculation stage. Therefore, viral titer is not concentration dependent in this stage. However, in the stages before and after viral inoculation, reduction of viral titer was dependent on concentration; in this regard, the highest significance was witnessed between 1 and 0.25 mg/ml concentrations (P < 0.05).

As can be observed in Figure 1, viral titer has a similar concentration-dependent decreasing pattern in all 3 stages. Furthermore, the amounts of reduction in virus titer are the same in the 0.25 mg/ml concentration in the simultaneous stage and the 0.5 mg/ml concentration in the pre-inoculation stage and the 1 mg/ml concentration in the post-inoculation stage (approximately Log102). In other words, a low concentration of the extract in the simultaneous stage has the same reducing effect on viral titer as a concentration twice as high in the previous stage and a concentration four times as high in the stage after viral inoculation. The highest decrease in viral titer, which equaled Log103.5, was witnessed in the highest tested concentration of the extract (1 mg/ml) in the simultaneous inoculation stage; the lowest decrease was observed in the lowest concentration in the post-inoculation stage, and it was different compared to the control group (Log103.5).

An analysis of this diagram reveals that using a higher concentration of cinnamon in the pre-inoculation stage would have an almost similar effect on viral titer as a lower concentration in the simultaneous inoculation stage. Moreover, although the extract can reduce the viral titer even after viral inoculation, it is only in the highest concentration that this effect is significant.

Now, since Ojagh et al. attributed strong antibacterial properties to cinnamaldehyde with a wide range of inhibiting effects against 5 types of bacteria,[18] and an evaluation stated that the phenolic compounds in essential oils, such as eugenol and cinnamic aldehyde in cinnamon, are the most common compounds with inhibiting effects;[19] it seems essential to research the influence of each cinnamon-derived compound on HSV-1. According to our study results, cinnamon extract is considered an effective medicine in the treatment of infections caused by HSV-1. Therefore, the compounds in this extract might be used in oral hygiene products such as mouthwash liquids, toothpastes, and gels. Cinnamon is an inexpensive and accessible herbal medicine with acceptable tissue adaptability used widely in food and health industries. However, the use of common systemic antiviral drugs is still recommended to people with weakened immune systems, severe and recurrent diseases, and cinnamon allergies. As a limitation, because of no plaque formation, it was not possible to measure the virus titer by counting the plaques. Hence, it is recommended to design and conduct in vivo studies on this substance as well as studies that apply other methods of measuring virus titer.

CONCLUSION

Hydroalcoholic extract of cinnamon can cause a significant reduction in the viral titer of herpes simplex type 1 in 3 stages: before, during, and after inoculation of herpes virus into the cell culture medium.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil

Conflicts of interest

The authors of this manuscript declare that they have no conflicts of interest, real or perceived, financial or non-financial in this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mortazavi H, Safi Y, Baharvand M, Rahmani S. Diagnostic features of common oral ulcerative lesions: An updated decision tree. Int J Dent. 2016:1–14. doi: 10.1155/2016/7278925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pan D, Flores O, Umbach JL, Pesola JM, Bentley P, Rosato PC, et al. Aneuron-specific host microRNA targets herpes simplex virus-1 ICP0 expression and promotes latency. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:446–56. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vashishtha AK, Kuchta RD. Effects of acyclovir, foscarnet, and ribonucleotides on herpes simplex virus-1 DNA polymerase: Mechanistic insights and a novel mechanism for preventing stable incorporation of ribonucleotides into DNA. Biochemistry. 2016;55:1168–77. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLaughlin MM, Sutton SH, Jensen AO, Esterly JS. Use of high-dose oral valacyclovir during an intravenous acyclovir shortage: A retrospective analysis of tolerability and drug shortage management. Infect Dis Ther. 2017;6:259–64. doi: 10.1007/s40121-017-0157-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arduino PG, Porter SR. Oral and perioral herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) infection: Review of its management. Oral Dis. 2006;12:254–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2006.01202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.An T, An J, Gao Y, Li G, Fang H, Song W. Photocatalytic degradation and mineralization mechanism and toxicity assessment of antivirus drug acyclovir: Experimental and theoretical studies. Appl Catal B Environ. 2015;164:279–87. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zinser E, Krawczyk A, Mühl-Zürbes P, Aufderhorst U, Draßner C, Stich L, et al. Anew promising candidate to overcome drug resistant herpes simplex virus infections. Antiviral Res. 2018;149:202–10. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Afshar B, Bibby DF, Piorkowska R, Ohemeng-Kumi N, Snoeck R, Andrei G, et al. AEuropean multi-centre External Quality Assessment (EQA) study on phenotypic and genotypic methods used for Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) drug resistance testing. J Clin Virol. 2017;96:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huynh T. Assessment of Traditional Chinese Herbal Medicine Plant Extracts' Potential to Inhibit Activity of Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1: University Honors College, Middle Tennessee State University. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Astani A, Navid MH, Schnitzler P. Attachment and penetration of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus are inhibited by melissa officinalis extract. Phytother Res. 2014;28:1547–52. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prince DJ. Effect of Chinese Knotweed Extract on HSV-1 Infection of Vero Cells. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Motamedifar M, Nekooeian A, Moatari A. The effect of hydroalcoholic extract of olive leaves against herpes simplex virus type 1. Iran J Med Sci. 2015;32:222–6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moradi MT, Rafieian-Kopaei M, Karimi A. A review study on the effect of Iranian herbal medicines against in vitro replication of herpes simplex virus. Avicenna J Phytomed. 2016;6:506–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reichling J, Schnitzler P, Suschke U, Saller R. Essential oils of aromatic plants with antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, and cytotoxic properties – An overview. Forsch Komplementmed. 2009;16:79–90. doi: 10.1159/000207196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bourne KZ, Bourne N, Reising SF, Stanberry LR. Plant products as topical microbicide candidates: Assessment of in vitro and in vivo activity against herpes simplex virus type 2. Antiviral Res. 1999;42:219–26. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(99)00020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benencia F, Courrèges MC. In vitro and in vivo activity of eugenol on human herpesvirus. Phytother Res. 2000;14:495–500. doi: 10.1002/1099-1573(200011)14:7<495::aid-ptr650>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ooi LS, Li Y, Kam SL, Wang H, Wong EY, Ooi VE. Antimicrobial activities of cinnamon oil and cinnamaldehyde from the Chinese medicinal herb Cinnamomum cassia blume. Am J Chin Med. 2006;34:511–22. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X06004041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ojagh SM, Rezaei M, Razavi SH, Hosseini SM. Investigation of antibacterial activity cinnamon bark essential oil (Cinnamomum zeylanicum) in vitro antibacterial activity against five food spoilage bacteria. J Food Sci Technol. 2012;9:67–76. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farahpour MR, Habibi M. Evaluation of the wound healing activity of an ethanolic extract of Ceylon cinnamon in mice. Vet Med. 2012;57:7–53. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fani MM, Kohanteb J. Inhibitory activity of Cinnamomum Zeylanicum and Eucalyptus Globulus Oils on Streptococcus Mutans, Staphylococcus Aureus, and Candida species isolated from patients with oral infections. J Dent Shiraz Univ Med Sci. 2011;11:14–22. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karber G. Beitrag zur kollectiven behandlung pharmacologischer reihenversuche. Arch Exp Path Pharmax. 1931;162:480–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buch K, Peters T, Nawroth T, Sänger M, Schmidberger H, Langguth P. Determination of cell survival after irradiation via clonogenic assay versus multiple MTT assay – A comparative study. Radiat Oncol. 2012;7:1. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monavari HR, Shamsi Shahrabadi M, Mortazkar P. The antiviral effects of Licorice extract on herpes simplex virus type A. J Med Plants. 2009;7:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghaemi A, Soleimanjahi H, Farshbaf Moghaddam M, Yazdani N, Zakidizaji H. Evaluation of antiviral activity of aerial part of Echinacea purpurea extract against herpes simplex virus type 1. Hakim. 2007;9:59–64. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zehtabian, Shahrabadi M. The antiviral effects of botany extract from marjoram on proliferation and replication herpes simplex virus type I. Sci J Ilam Med Univ. 2008;16:28–36. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monavari HR, Hamkar R, Nowrouzbabaie Z, Adibi L, Nowrouz M, Ziyaie A. The antiviral effects twenty-five different species of medicinal plants Iran. Iran J Med Microbiol. 2008;1:49–59. [Google Scholar]