Abstract

The use of personal protective equipment (PPE) has skyrocketed, as providers don masks, glasses, and gowns to protect their eyes, noses, and mouths from COVID-19. Yet these same facial features express human individuality, and are crucial to nonverbal communication. Isolated ICU patients may develop “post intensive-care syndrome,” which mimics PTSD with sometimes debilitating consequences. While far from a complete solution, PPE Portraits (disposable portrait picture stickers - 4" × 5") have the potential to humanize care. Preparing for a larger effectiveness evaluation on patient and provider experience, we collected initial qualitative implementation insights during Spring 2020’s chaotic surge preparation. Front-line providers reported more comfort with patient interactions while wearing PPE Portraits: “It makes it feel less like a disaster zone [for the patient].” A brief pilot showed signs of significant adoption: a participating physician requested PPE Portraits at their clinic, shift nurses had taken PPE Portraits with them to inpatient services, and masked medical assistant team-members requested PPE Portraits to wear over scrubs. We believe PPE Portraits may support patient care and health, and even potentially healthcare team function and provider wellness. While we await data on these effects, we hope hospitals can use our findings to speed their own implementation testing.

The use of personal protective equipment (PPE) has skyrocketed during the COVID-19 crisis, as providers don masks, glasses, and gowns to protect their eyes, noses, and mouths. Yet these same facial features express human individuality, and are crucial to nonverbal communication. Even in a crisis, human connection is at the core of medical care,1 and PPE, while necessary, can interrupt that connection.2

Especially for COVID-19 patients needing ICU care, some worry that a lack of human connection can have adverse effects beyond simple satisfaction or patient experience measures. Studies have shown that isolated ICU patients may develop “post intensive-care syndrome,” which mimics PTSD with sometimes debilitating consequences. A 2010 systematic review of patients placed in contact isolation for infection control showed adverse impacts of isolation on mental well-being, satisfaction, and several measures of patient safety.3 Conversely, provider warmth and compassion have been positively associated with physiological health biomarkers, and researchers have called for testing interventions to promote perceptions of kindness.4

Healthcare workers across the USA intent on humanizing the COVID-19 experience have innovated alternative communication methods to bridge the gap between PPE-covered provider and patient. At Parkland Hospital, providers created handouts with photos, names, and reassuring text (“Dear Friend…you are in the hands of people who care about your health”). Stanford Hospital, among many others, is implementing virtual rounding, which allows providers to meet “face-to-face” with hospitalized patients over secure video prior to in-person physical exams during which their features will be necessarily obscured.

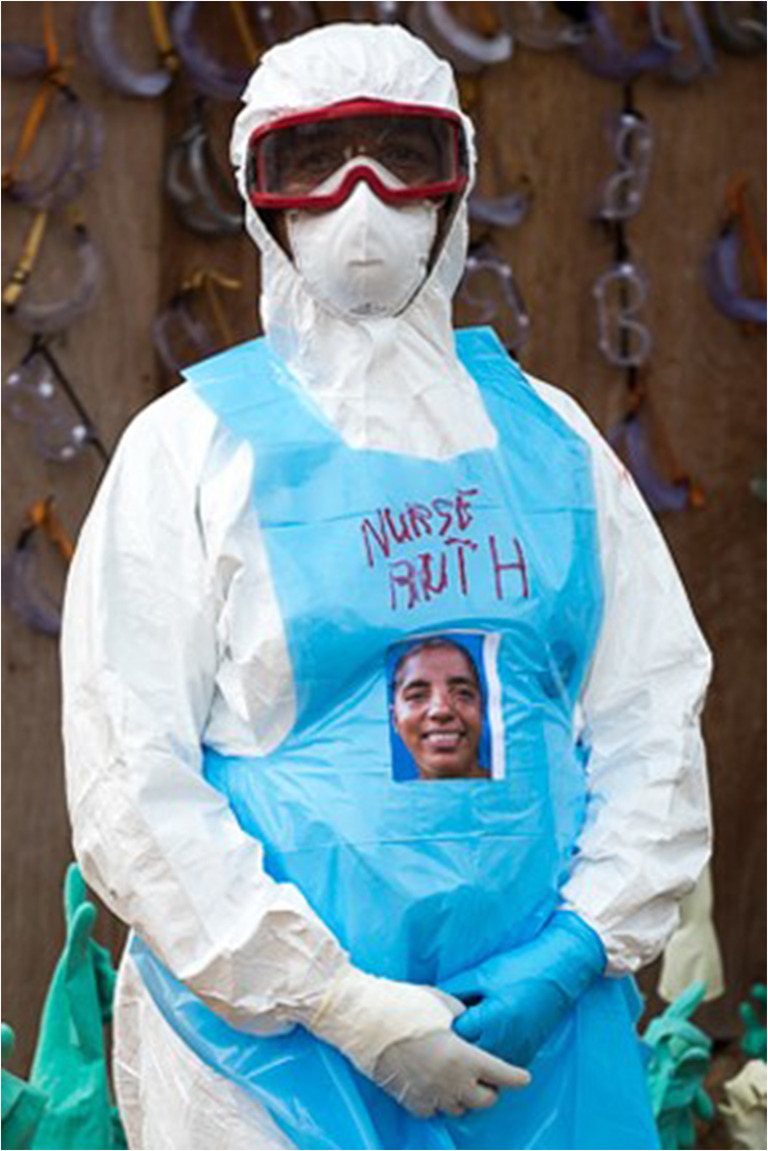

While far from a complete solution, PPE Portraits also have the potential to help humanize care in difficult times. They are simply disposable provider portrait picture stickers (4" × 5") affixed to PPE where patients can see them. Anecdotal pilot data captured during treatment of Ebola showed that PPE Portraits helped patients feel more connected to their caregivers, and helped healthcare workers feel more like a team and connected to one another, though this has yet to be rigorously studied (Figs. 1).5

Figure 1.

PPE Portrait Project “Nurse Ruth” (Ruth Haddad Johnson, RN) during the Ebola crisis, photo credit Mary Beth Heffernan.

In partnership with the designer of the original PPE Portrait Project in Africa, Mary Beth Heffernan, Stanford Express Care is piloting PPE Portraits for the newly created drive-thru COVID-19 testing.6 Similarly, the inpatient palliative care team at UMass Memorial Medical Center has begun using PPE Portraits in caring for seriously ill patients in the hospital, regardless of infection status.

In preparation for a larger evaluation of the effectiveness of PPE Portraits on patient and provider experience, we collected initial qualitative data on implementation barriers and facilitators during the chaotic surge preparation activities of March and April 2020. We share practical lessons for implementing similar programs for others to use.

Front-line providers reported more comfort with patient interactions while wearing PPE Portraits: “It makes it feel less like a disaster zone [for the patient].” Just a 2-day pilot showed signs of significant adoption: a participating physician requested PPE Portraits at a new COVID-19 clinic, shift nurses had taken PPE Portraits with them to inpatient services, and masked medical assistant team-members were requesting PPE Portraits to wear over scrubs.

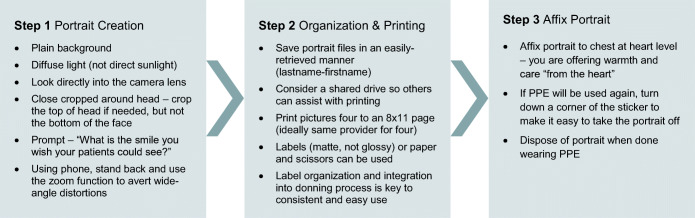

Using the process in Figure 2, we took smartphone portraits, electronically pasted four portraits on an 8" × 11" template, and printed. We also developed workarounds and contingencies. After running out of stickers during high volume, we printed extra copies to have some on reserve. Since full color portraits use large amounts of ink, we kept a close eye on printer supplies. We also tested printing PPE Portraits on nonsticker paper in case sticker supplies dwindled, and we explored the idea of affixing these pictures on PPE with masking tape.

Figure 2.

PPE Portraits—process.

PPE Portraits are a simple intervention with the potential to improve COVID-19 care. Of course, in our April 2020 US context, needed PPE itself is not always available, let alone the clinician or administrator time needed to take and print portrait photos to stick on full PPE. Preparing PPE Portraits or other humanizing approaches in anticipation of surges would have been much preferred. Still we believe PPE Portraits may support patient care and health, and even potentially healthcare team function and provider wellness. While we await data on these effects, we hope hospitals can use our findings to speed their own implementation testing.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge and thank providers and staff in Stanford Express Care—particularly Maja K. Artandi MD, Linda Barman MD, Heather Filipowizc MS RD—and to thank Timothy Seay-Morrison EdD and Megan Mahoney MD for their support and interest in this quality improvement project.

Compliance with Ethical Standards. This project recieved a quality improvement exemption from Stanford IRB (protocol # 55708)

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Zulman DM, Haverfield MC, Shaw JG, et al. Practices to Foster Physician Presence and Connection with Patients in the Clinical Encounter. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323:70–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.19003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pallister-Wilkins P. Personal Protective Equipment in the humanitarian governance of Ebola: between individual patient care and global biosecurity. Third World Q. 2016;37:507–523. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2015.1116935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abad C, Fearday A, Safdar N. Adverse effects of isolation in hospitalised patients: A systematic review. J Hosp Infect. 2010;76:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trzeciak S, Roberts BW, Mazzarelli AJ. Compassionomics: Hypothesis and experimental approach. Med Hypotheses. 2017;107:92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2017.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Integration of the Humanities and Arts with Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine in Higher Education. National Academies Press; 2018. 10.17226/24988 [PubMed]

- 6.Thomas SC, Carmichael H, Vilendrer S, Artandi M. Integrating telemedicine triage and drive-through testing for COVID-19 rapid response (Stanford, 3/18). Heal Manag Policy Innov. 2020.