Background: Some patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) progress rapidly to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), septic shock, and multiple organ failure (1). Some experts attribute this sequence of events to a large increase in cytokines (cytokine storm) caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) or a secondary infection by another organism.

Objective: To report cytokine levels in multiple body fluids from a patient with COVID-19 and ARDS, septic shock, and multiple organ failure.

Case Report: On 20 January 2020, a 66-year-old man who had been exposed to a patient with COVID-19 developed cough and fever and treated himself at home. On 2 February, his cough and fever gradually worsened, his body temperature reached 38.7 °C, and he developed diarrhea and vomiting. He was treated at a local hospital, where his medical history included vitiligo, gastric ulcer, coronary heart disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He developed dyspnea 2 days later, and COVID-19 was diagnosed by a throat swab that was tested for nucleic acid. He received the antiviral drug abidol and supportive care. When his dyspnea worsened, he was transferred to the intensive care unit for noninvasive mechanical ventilation. On 11 February, mechanical ventilation was started because of a progressive decrease in blood oxygen saturation, a blood lactate level of 4 mmol/L, and a PaO2–FiO2 ratio of 186 mm Hg.

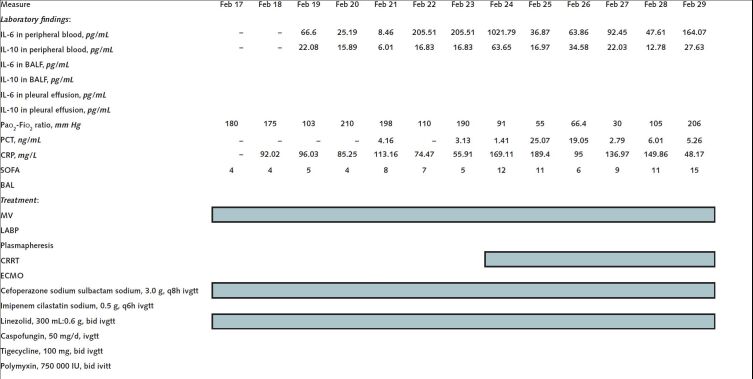

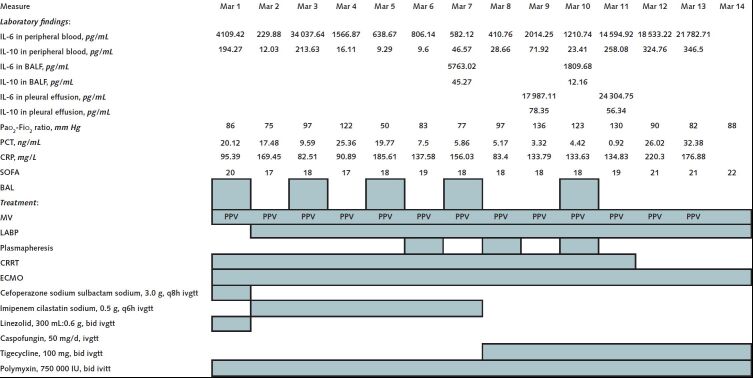

On 17 February, the patient was transferred to the Severe COVID-19 Intensive Treatment Center of Heilongjiang Province. His COVID-19 status was confirmed as a critical type, according to guidelines from the National Health Commission (trial version 7). We treated him with antiviral drugs, immunoglobulin infusions, lung-protective ventilation, and lung recruitment and prone position ventilation. In addition, we started measuring levels of the cytokines IL-6 and IL-10 in his blood daily and in his bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and pleural fluid intermittently, and we found high levels (Figure). On 23 February, we started continuous renal replacement therapy with an Oxiris filter (Baxter International), which is designed to adsorb uremic toxins, endotoxin, and cytokines. Computed tomography on 24 February showed worsening of pulmonary inflammation. On 1 March, we started extracorporeal membrane oxygenation because we could not maintain the patient's oxygenation with intermittent prone position ventilation. On 2 March, the patient developed septic shock and cardiac insufficiency, and we introduced an intra-aortic balloon pump. On 6 March, every-other-day plasmapheresis was started in another attempt to decrease his cytokine levels. Computed tomography on 9 March showed that the patient's lung consolidation had worsened. Unfortunately, the patient died on 14 March.

Figure.

Laboratory findings and treatment in February 2020 and March 2020.

BAL = bronchoalveolar lavage; BALF = bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; CRP = C-reactive protein; CRRT = continuous renal replacement therapy; ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; IABP = intra-aortic balloon pump; ivgtt = intravenously guttae; MV = mechanical ventilation; PCT = procalcitonin; PPV = prone position ventilation; SOFA = Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Figure.

Continued

Discussion: The role of cytokine storm in patients with COVID-19 is uncertain. We measured levels of IL-6 and IL-10 during this patient's illness to see whether they could help us decide how to modify his treatment as the disease progressed. We found high and fluctuating levels of these cytokines in his peripheral blood, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, and pleural fluid. However, these levels correlated only inconsistently with the treatments we administered, even for plasmapheresis, which was intended to dilute circulating cytokines, and for a dialysis filter that was designed to adsorb cytokines (Figure). In addition, these cytokine levels correlated inconsistently with his clinical course, except that the levels increased dramatically in the last days before he died.

We suspect that this patient's immune system was partially suppressed due to his advanced age and multiple chronic conditions, which might have contributed to the virus's continued replication and the disease's progress. In addition, the time from symptom onset to confirmation of COVID-19 diagnosis was relatively long, the patient's hospital course was longer, and we wonder whether this long duration of viral replication contributed to the high cytokine levels we measured.

Other studies have reported that patients with COVID-19 have evidence of local damage, which includes diffuse alveolar injury with cellular fibrous mucus-like exudates (2). We measured IL-6 levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid that were higher than the corresponding serum levels. On one occasion (7 March), the IL-6 level was approximately 10 times higher. This difference is even more remarkable because the process of collecting bronchoalveolar fluid dilutes the specimen. In addition, the level of IL-6 in pleural effusion was higher than the corresponding serum levels on the 2 times we measured it. If these observations indicate a cytokine storm, we propose that the local storm may be worse than the systemic storm.

Interleukin-6 blockers have been used to treat cytokine storm in patients with other causes of cytokine storm (3), and tocilizumab has been suggested for immunotherapy for severe patients with extensive lung lesions and elevated IL-6 levels (3). As a result, we wonder whether tocilizumab would have affected the IL-6 levels we observed and whether it might have improved this patient's disease course, especially because others have reported that as COVID-19 progresses to its middle and late stages, the expression of inflammatory cytokines is related to the severity of the disease (4). On the basis of our experience, we encourage additional research to determine whether inflammatory cytokines in the lungs predict the clinical course of COVID-19 and whether these cytokines should be a target for intervention and treatment.

In summary, this case suggests an increased inflammatory response in the lung tissues of critically ill patients with COVID-19, and it suggests that future research should include examinations of local inflammation in the lungs.

Biography

* Drs. Wang, Kang, Gao, Ye, Lan, and Li contributed equally.

Financial Support: By the novel coronavirus pneumonia emergency treatment and diagnosis technology research project of Heilongjiang Provincial Science and Technology Department, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81571871, 81770276), and Nn10 program of Harbin Medical University Cancer Hospital.

Disclosures: Authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest. Forms can be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors/icmje/ConflictOfInterestForms.do?msNum=L20-0354.

Acknowledgment: The authors thank the staff of the Severe COVID-19 Intensive Treatment Center of Heilongjiang Province for their bravery and dedication.

Corresponding Author: Ming-Yan Zhao, MD, Department of Critical Care Medicine, the First Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, No. 23 Youzheng Street, Harbin 150001, Heilongjiang Province, China (e-mail, mingyan0927@126.com); or Kaijiang Yu, PhD, Department of Critical Care Medicine, the First Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, No. 23 Youzheng Street, Harbin 150001, Heilongjiang Province, China (e-mail, drkaijiang@163.com).

Footnotes

This article was published at Annals.org on 12 May 2020.

References

- 1. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507-513. [PMID: 32007143] doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y, et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:420-422. [PMID: 32085846] doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000043. Barrett DM, Teachey DT, Grupp SA. Toxicity management for patients receiving novel T-cell engaging therapies. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2014;26:43-9. [PMID: 24362408] doi:10.1097/MOP.0000000000000043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497-506. [PMID: 31986264] doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]