Sir,

The description of a novel human coronavirus initially referred to as the Wuhan coronavirus (CoV), currently designated as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-CoV-2 as per the latest International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) classification1 is probably the most recent human pneumonia virus with high outbreak potential. This novel virus was initially identified through next-generation sequencing (NGS) and suggested to have a possible zoonotic origin2. Till date, detailed morphology and ultrastructure of this virus remains incompletely understood.

In India, the first laboratory-confirmed infection by SARS-CoV-2 was reported on January 30, 2020 (unpublished data). The throat swab from this case was kept in commercially available transport medium (HiViral™ Transport Medium, HiMedia, Mumbai). A 500 μl aliquot from this specimen that had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was centrifuged to remove the debris. The supernatant was removed, fixed at a final concentration of one per cent glutaraldehyde and adsorbed onto a carbon-coated 200 mesh copper grid. Negative staining was done with sodium phosphotungstic acid as described earlier3. The grid was examined under 100 kV accelerating voltage in a transmission electron microscope (TEM) Tecnai 12 BioTwin™ (FEI Company, The Netherlands). Imaging was done using a low-dose mode and images were captured using a side-mounted 2k × 2k CCD camera (Megaview III, Olympus, Japan).

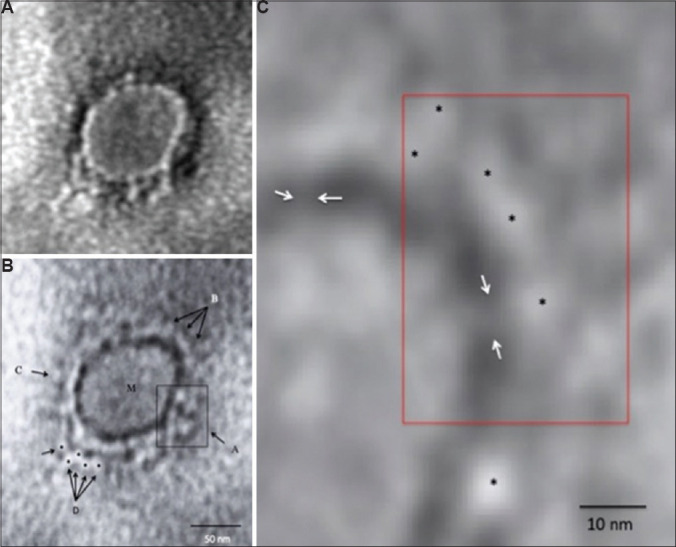

A total of seven negative-stained virus particles having morphodiagnostic features of a coronavirus-like particle could be imaged in the fields scanned. These included the round shape of the virus with an average size of 70-80 nm and a cobbled surface structure having envelope projections that averaged 15±2 nm in size. One particular virus particle was very well preserved, showing very typical morphodiagnostic features of coronaviruses4. This particle was 75 nm in size and showed patchy stain pooling on the surface and a distinct envelope projection ending in round 'peplomeric' structures (Figure A). We used a mild defocussing of the projector lens away from the conventional Fresnel focus in an attempt to image the finer details of the envelope projections. All focusing operations were carried out using a Fourier fast focus transform under the TIA imaging software (FEI Company, The Netherlands). The defocussed image under low-beam current conditions prominently brought out the finer morphology of the SARS-CoV-2 virus surface projection as typical of a coronavirus (Figure B). We further increased the magnification under low-dose image capture and generated a pixel-corrected image of the projection to image single glycoprotein organization. The image revealed the presence of stalk-like projections ending in round peplomeric structures typical of a coronavirus particle (Figure C).

Figure.

Transmission electron microscopy imaging of COVID-19. (A) A representative negative-stained COVID-19 particle showing morphodiagnostic features of family Coronaviridae. (B) Defocussed image of the same particle resolving the virus envelope glycoprotein morphology in finer details. The boxed area A shows a tetramer-like aggregate of four distinct peplomers, arrows shown by B show a more orthodox morphology of coronavirus surface projections. M indicates the matrix of the virus particle. C shows a distinct 'peplomer head' with negative stain silhouette. The area D is interesting as possible linear projections could be imaged. Five distinct peplomers could be imaged as shown by the arrows. (C) A highly magnified processed image for pixel corrections shows a distinct evidence of direct 'stalk' connecting the peplomer to the virion surface. The peplomers are shown with asterisk and the stalk with an arrow. Magnification bars are built into the micrographs.

Interestingly, the envelope fringe of the SARS-CoV-2 virus particle imaged by us showed an interesting feature when compared to the classic description of human coronaviruses5. This included a relatively shorter size and a possible multi-aggregate of the peplomers (Figure B). This morphological variation could be due to a fixation artefact in clinical material. Imaging the cell culture-derived virus will resolve this point effectively. The limited imaging of a few virus particles has an intrinsic imaging limitation.

Further, imaging thin sections from infected cells by conventional and cryo-ultramicrotomy methods, like that of Tokyasu6, will further provide more detailed information on the macromolecular assembly and organization of SARS-CoV-2. The use of single-particle reconstruction of the purified virus using CryoEM will also give high-resolution organizational details of the mature virion and complete surface glycoprotein organization. A recent cryoEM study imaging the purified envelope spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 has reconstructed three-dimensional images at 3.2 Å resolution7. While a series of informal reports are available on electron microscopy of the SARS-CoV-2 from Hong Kong University researchers8, no detailed studies on ultrastructural cytopathology are available till date.

In summary, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report from India detecting the SARS-CoV-2 virus using TEM directly in a throat swab specimen confirmed by PCR. Although TEM imaging was limited by particle load in the specimen, we could still detect morphologically identifiable intact particles in stored clinical sample without initial fixation. Imaging other specimens such as stool and use of immunoelectron microscopy techniques can improve the detection frequency of virus in direct clinical material. This finding emphasizes the merit of the use of conventional negative-stained TEM imaging in clinical samples along with other diagnostic tests in parallel, especially in situ ations identifying aetiologic agents9.

Acknowledgment

Authors thank all members of the ICMR-NIV National Influenza Center Team.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Gorbalenya AE, Baker SC, Baric RS, de Groot RJ, Drosten C, Gulyaeva AA, et al. The species severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat Microbiol. 2020. https://doiorg/101038/s41564-020-0695-z . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brenner S, Horne RW. A negative staining method for high resolution electron microscopy of viruses. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1959;34:103–10. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(59)90237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldsmith CS, Ksiazek TG, Rollin PE, Comer JA, Nicholson WL, Peret TC, et al. Cell culture and electron microscopy for identifying viruses in diseases of unknown cause. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:886–91. doi: 10.3201/eid1906.130173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madeley CR, Field AM. In: Virus morphology. 2nd ed. Field AME, editor. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griffiths G, McDowall A, Back R, Dubochet J. On the preparation of cryosections for immunocytochemistry. J Ultrastruct Res. 1984;89:65–78. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(84)80024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wrapp D, Wang N, Corbett KS, Goldsmith JA, Hsieh CL, Abiona O, et al. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 2020 doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507. pii: eabb2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.HKUMed on COVID-19. Latest updates from the faculty. [accessed on February 28, 2020]. Available from: https://wwwmedhkuhk/en/The-Latest-from-HKUMed-on-COVID-19 .

- 9.Hazelton PR, Gelderblom HR. Electron microscopy for rapid diagnosis of infectious agents in emergent situations. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:294–303. doi: 10.3201/eid0903.020327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]