The carnage continued. “Trauma Alert. Police drop off. GSW. ETA now.” It was the fourth overhead page in the last 2 hours. One gunshot (GSW) victim was already on the operating room table for repair of a major vascular injury; another was being wheeled upstairs for an urgent thoracotomy after being shot in the chest. The next had arrived pulseless, unable to be resuscitated in the trauma bay. Now the fourth. More surgeons came in from home. This was a Sunday afternoon. All nonessential businesses were closed, and Philadelphia County remained under a “Stay At Home” order. But the trauma alert pages did not stop.

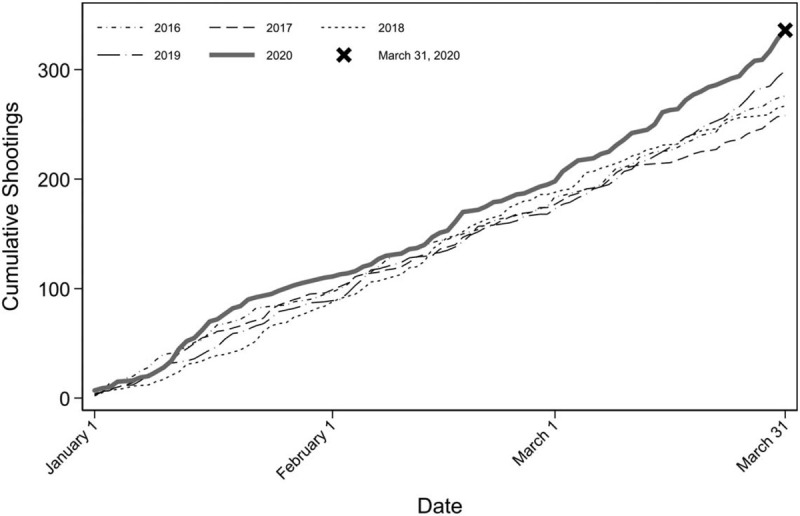

In recent weeks, there has been near-constant—and appropriate—focus on the toll of the SARS-CoV-2 in the United States and abroad. As of this writing, there are nearly 450,000 confirmed cases and >14,000 deaths in the United States, with confirmed cases surpassing 1.5 million worldwide.1 But other diseases, like firearm injuries, continue unabated. At best, interpersonal violence is taking place at baseline rates; at worst, violence is escalating. And it feels that way to all of us working in urban trauma centers. Recent data support this observation. In Philadelphia, there were 141 shootings in March, making it Philadelphia's worst March for gun violence in 5 years. During the first 10 days alone of Philadelphia's “Stay At Home” order, there were 52 shooting victims in the city (Fig. 1).2

FIGURE 1.

Philadelphia Shootings, 2016–2020.

The basis for this uptick is unclear. It is hard to say at this point whether the phenomenon we have seen represents a significant increase or random variation—only time will tell—but orders to stay at home are certainly not reducing gun violence. As we have seen from early data, COVID-19 affects racial and socioeconomic groups differently, likely due in part to the fact that many cannot afford to stay home.3,4 The inability of society's most disadvantaged groups to abide by a “Stay At Home” order, combined with the heightened stress of the pandemic, may in part explain the current increase in interpersonal violence.

Whatever the reason, the timing of the increase in violence we have seen gives us pause. At the same time that we are experiencing an uptick in gun violence, our hospitals and trauma centers are grappling with a pandemic the likes of which has not been seen in more than a century. It is not clear whether this escalation in violence will persist; however, it comes at a time of limited resources, when any violence puts an unnecessary strain on the hospital system.5 Critical resources necessary to care for these victims of firearm violence, such as personal protective equipment (PPE), intensive care beds, blood products, and even hospital staff, are all perilously depleted.

In light of the recent increase in violence, a surge in gun sales, driven by public panic and unfounded fears that guns would soon be in short supply, is particularly troubling. Gun shops with long lines are a common observance in our communities. Initially determined to be non-“life-sustaining businesses," such stores were briefly ordered to close, but have subsequently been added to the Pennsylvania essential services list and re-opened quickly.5 Across the United States, >1 million more background checks were performed in March 2020 than in March 2019, with the research firm Small Arms Analytics & Forecasting (SAAF) estimating a 91% increase in handgun sales between the same 2 months.6 An increasing number of guns in circulation at a time of high stress will have unintended consequences. There is concern over the effect that “Stay At Home” orders may have on domestic violence; indeed, the risk of death among victims of domestic abuse is increased 5-fold with a gun in the home.7

Steps to mitigate violence, or at a minimum adequately prepare for its toll during the COVID-19 pandemic, should be taken. The first step is recognition that the problem of interpersonal violence is persisting and potentially worsening. With around-the-clock news coverage and inbox saturation regarding COVID-19, it may be easy to lose track of the “usual” patients. We might have hypothesized a month ago that “Stay At Home” orders would reduce firearm violence, but we have seen the opposite in our community and remain concerned about the potential for increases in the volume of intimate partner violence and child abuse victims that we see. Patients will continue to require our attention and resources.

In managing this pandemic, centers should develop COVID-19-relevant protocols. With the strain on resources and uncertainty of COVID-19 status in patients that cannot be screened (eg, intubated patients or those with depressed mental status), our institution has dedicated part of the trauma bay for these patients. Rapid testing is used before transfer to the intensive care unit—if clinically appropriate—to triage patients to negative pressure rooms and COVID-19 dedicated units in an attempt to reduce exposures. N95 masks are now standard for all trauma resuscitations and aero-digestive procedures. Although presently we are fortunate enough to have adequate PPE at a time when shortages have become a national issue, conservation of equipment is imperative. We reuse items when appropriate, carefully plan procedures so as to limit entrances and exits from a patient's room, and limit the number of providers participating in procedures to the minimum possible. An increase in the volume of violence also increases the need for PPE use. Now is the time for national guidelines and best practices for trauma systems around the country in the context of a pandemic. We must keep our workforce healthy and able to care for all patients for the long haul.

Limited resources should be managed with care. Blood shortages, lack of PPE, and lack of beds and personnel should compel institutions to allocate selectively. Standardized guidelines based on an institution's supply are beneficial and need to be continuously updated. Although we are all inclined to continue to provide operative care to patients in need, we must be exceptionally prudent and operate on only those patients with life-threatening problems. Our health system has put in place a requirement that all nonemergent cases require “justification” from the attending surgeon as part of the scheduling process. We applaud this change and urge others to do the same. As this pandemic progresses, it may force us into the uncomfortable position of weighing maximum public health benefit against individual patient benefit. Difficult decisions may have to be made at the institution level regarding allocation of scarce resources like blood products, ventilators, and advanced therapies like extracorporeal membranous oxygenation.

Finally, physical distancing must be coupled with social support. Although distancing measures will undoubtedly mitigate the viral epidemic, we cannot allow it to exacerbate the violence epidemic. The fact that violence has persisted in Philadelphia despite orders to stay home may say something about the risk/benefit calculus in our trauma patients. Although many people are consumed by the fear of virus transmission, for some, this risk pales in comparison to the baseline risk of community violence and is superseded by the need to carry on with everyday activities for survival. Isolating and abandoning society's most vulnerable members will only trade one cause of mortality for another. Access to social services must be maintained. Economic and emotional stressors need to be minimized. We cannot lose sight of the fact that all gun injuries are preventable. Our country's social safety net is needed now more than ever.

The last month in our city has shown us that gun violence does not stay home. In this country, violence does not stop for anything, even in the face of a global pandemic. It is imperative that we stay focused and prepared, since the pages will continue overhead.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

REFERENCES

- 1. Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University. Coronavirus Resource Center [Internet]. [April 9, 2020]. Available from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2. City of Philadelphia. OpenDataPhilly: Shooting Victims [Internet]. [April 2, 2020]. Available from: https://www.opendataphilly.org/dataset/shooting-victims. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Talev M. Axios-Ipsos Coronavirus Index: Rich sheltered, poor shafted amid virus. Axios [Internet]. April 9, 2020. Available from: https://www.axios.com/axios-ipsos-coronavirus-index-rich-sheltered-poor-shafted-9e592100-b8e6-4dcd-aee0-a6516892874b.html. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eligon J, Burch ADS, Searcey D, Oppel Jr. RA. Black Americans Face Alarming Rates of Coronavirus Infection in Some States. The New York Times. April 7, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5. The Inquirer Editorial Board. When coronavirus and gun violence collide, it makes both more deadly. The Philadelphia Inquirer. March 26, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Druzin H. Gun Sales Skyrocket In March On Pandemic Fears. Guns & America [Internet]. April 1, 2020. Available from: https://gunsandamerica.org/story/20/04/01/gun-sales-skyrocket-in-march-on-pandemic-fears/. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell JC, Webster D, Koziol-McLain J, et al. Risk factors for femicide in abusive relationships: results from a multisite case control study. Am J Public Health 2003; 93:1089–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]