Surgeons are finding themselves in uncharted territory; our bandwidth has been increased. With clinics and elective surgeries cancelled, in-hospital service responsibilities at an all-time low, and educational responsibilities abbreviated, there is a lack of the usual stimuli for the “urgency addiction” that drives many of our lives. Surgeons with seniority are fulfilling disaster management roles at the institution, regional, and national levels. Those of us, perhaps the less seasoned surgeons, who are not part of the higher-level protocol and policy development process, are searching for ways to contribute to the greater good of the COVID-19 response efforts. We propose a call to action for these surgeons to operate outside the box, without a blade, and assist in the role of palliative care physicians.

As our responsibilities caring for surgical patients has temporarily lightened, the patient load for specialty palliative care services has skyrocketed.1 With in-hospital visitor restrictions, communication between families and medical teams caring for critically ill patients has become increasingly challenging. The overall provider workforce has been minimized to reduce exposure, and as such, the remaining frontline stakeholders are focused on clinical care tasks at hand. Concomitantly, the specialty palliative care groups have the added burden of COVID-specific needs in the ED, acute care floors, and intensive care units (ICU). As a consequence, surgical patients’ palliative care needs are not being met in an adequate or timely fashion. However, surgeons can step forward to help address this growing problem.

Each surgical group and institution would benefit immensely from having a surgical palliative care champion (SPCC). In the current crisis, the SPCC will function as the liaison between surgeons and palliative care physicians. They will advise their surgical colleagues on the changing policies with regards to institutional resuscitation policies, informed assent processes, and determining durable power of attorney for hospitalized patients without a surrogate decision-maker.2 In preparation for reallocation of surgeons to care for the critically ill, the SPCC becomes the go-to surgeon for support in conducting goals of care conversations and end-of-life symptom management.3 The SPCC will serve in the just-in-time educator role for other surgeons and may also be able to educate and prepare their group in advance if they practice in an area of the country that is afforded the luxury of time. Lastly, the SPCC will have their finger on the pulse of the ethical climate of the institution and provide updates to their group on the regional and national shifts in triaging practices and allocation of scarce resources as the crisis escalates.4

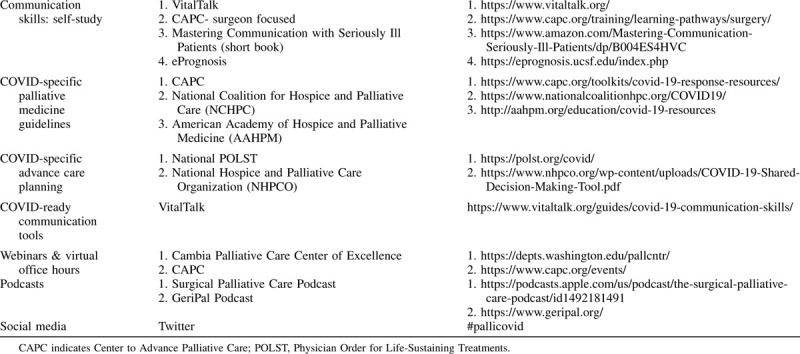

The first step is to establish the dedicated SPCC. From this point, much of the work can be done remotely, keeping in line with physical distancing and stay-at-home mandates. Well-established resources for self-improvement in communication skills are available online free of charge (Table 1). In the crisis setting, there is ample opportunity to perfect these skills and develop an optimal routine. The Center to Advancing Palliative Care (CAPC) has developed an extensive COVID-specific toolkit including and not limited to goals of care conversation scripts, telemedicine utilization guidance, symptom management recipes, and billing for virtual visits. Distribution of scripts and recipes to surgeons on the frontlines (including residents) will help ease the anxiety of practicing outside of their usual realm. The SPCC will stay updated on the changing landscape by joining virtual palliative care specialty meetings at the institution and national levels. Palliative care practitioners are a wonderfully welcoming group, and incredibly supportive of surgeons joining their cause.

TABLE 1.

Palliative Medicine Resources for SPCCs

Surgical palliative care has been a growing field in recent years. According to the American Board of Surgery, there are 80 surgeons board certified in Hospice and Palliative Medicine (HPM). However, there is increasing interest among young surgeons to obtain advanced communication skills training and serve as a SPCC for their group, without completing a formal HPM fellowship. Furthermore, medical students and residents are expected to be trained in skills such as organizing family meetings, navigating goals of care discussions, and end-of-life care as integral components of high-quality surgical care. There is an opportunity looming within the context of the COVID-19 crisis for surgeons with an interest in palliative care to step into this role, join the surgical palliative care community, and potentially foster a whole new career path.

With the SARS-CoV2 outbreak in Seattle, we identified unmet palliative care needs in our surgical population early in the COVID-19 pandemic. In response to this, we created a surgical palliative care service that is dedicated to caring for surgical patients. Our goals were to prioritize meeting surgical patients’ needs, reduce unwanted aggressive end of life treatments in light of limited resources, and offload the specialty palliative care team. The team consists of 1 attending surgeon and 1 nurse coordinator who is embedded in the Trauma/Surgical ICU. All family meetings are conducted virtually, and a medical scribe documents the conversations. Nights and weekend call coverage is provided by the specialty palliative care team. Importantly, for non-COVID older adults expected to survive to hospital discharge, goals of care conversations include COVID-specific advance care planning. Some older adults with underlying comorbidities are electing to avoid hospitalization and remain at home with family providing comfort-focused treatments in the case they develop COVID-19. A new Physician Order for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) form reflecting these wishes is sent with the patient on hospital discharge. Feedback from families, intensivists, surgeons, nurses, and our palliative care colleagues has been overwhelmingly positive.

The need for palliative medicine has grown exponentially in the last few weeks. Surgeons can help meet the demand, and in doing so, greatly benefit themselves and their patients for the entirety of their careers. The foundation of Surgical Palliative Care is solid and the trail for surgeons to practice both surgery and palliative medicine is ready to be blazed.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fausto J, Hirano L, Lam D, et al. Creating a palliative care inpatient response plan for COVID19—the UW medicine experience [published online ahead of print March 20, 2020]. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curtis JR, Kross EK, Stapleton RD. The importance of addressing advance care planning and decisions about do-not-resuscitate orders during novel Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.You JJ, Fowler RA, Heyland DK. Just ask: discussing goals of care with patients in hospital with serious illness. CMAJ 2014; 186:425–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White DB, Katz MH, Luce JM, et al. Who should receive life support during a public health emergency? Using ethical principles to improve allocation decisions. Ann Intern Med 2009; 150:132–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]