Summary

Spatially and functionally distinct domains of heterochromatin and euchromatin play important roles in maintenance of chromosome stability and regulation of gene expression, but a comprehensive knowledge of their composition is lacking. Here we develop a strategy for isolation of native Schizosaccharomyces pombe heterochromatin and euchromatin fragments and analyze their composition using quantitative mass spectrometry. The shared and euchromatin-specific proteomes contain proteins involved in DNA and chromatin metabolism, and transcription, respectively. The heterochromatin-specific proteome includes all proteins with known roles in heterochromatin formation and, in addition, is enriched for subsets of nucleoporins and inner nuclear membrane (INM) proteins, which associate with different chromatin domains. While the INM proteins are required for the integrity of the nucleolus, containing ribosomal DNA repeats, the nucleoporins are required for aggregation of heterochromatic foci and epigenetic inheritance. The results provide a comprehensive picture of heterochromatin-associated proteins and suggest a role for specific nucleoporins in heterochromatin function.

Graphical Abstract

eTOC Blurb

Iglesias et al. describe a strategy for identification of proteins associated with native heterochromatin and euchromatin DNA domains. In addition to previously identified proteins, the heterochromatin-specific proteome contains inner nuclear membrane proteins and a specific subset of nucleoporins, some of which function in epigenetic inheritance and clustering together of distal heterochromatic regions.

Introduction

Eukaryotic chromosomes are organized into structurally and functionally distinct domains called heterochromatin and euchromatin, which represent transcriptionally silent and active genomic regions, respectively (Allshire and Madhani, 2018, Heitz, 1928). Heterochromatin is composed of gene poor, repetitive DNA sequences, and transposons, and plays a critical role in maintenance of genome stability. Heterochromatic DNA domains in organisms ranging from fission yeast to human are packaged with nucleosomes that contain hypoacetylated histones and histone H3 lysine 9 di- and trimethylation (H3K9me2 and H3K9me3, respectively). Another nearly invariant feature of heterochromatic domains is their localization to the nuclear periphery as bodies or foci (Towbin et al., 2013, Mekhail and Moazed, 2010). Genetic and biochemical studies have identified many of the key components required for heterochromatin formation but a comprehensive knowledge of heterochromatin composition, and in particular how these domains form foci and are localized to the nuclear periphery is lacking.

In the fission yeast S. pombe, pericentromeric DNA repeats, subtelomeric DNA regions, and the mating type (mat) locus are assembled into heterochromatin (Wang et al., 2016). The establishment of heterochromatin at these regions involves recruitment of the histone H3K9 methyltransferase Clr4 (Suv39h) by RNAi-dependent and RNAi-independent pathways (Holoch and Moazed, 2015a). H3K9 methylation then leads to recruitment of Swi6 and Chp2, homologs of metazoan HP1 proteins, which are required for recruitment of downstream factors and heterochromatin formation (Lachner et al., 2001, Bannister et al., 2001, Nakayama et al., 2001, Rougemaille et al., 2012, Hayashi et al., 2012, Yamada et al., 2005, Motamedi et al., 2008). At the cytological level, the assembly of functional heterochromatin correlates with the formation of a limited number of bodies or foci, in which heterochromatic DNA domains and proteins coalesce and localize to the nuclear periphery (Akhtar and Gasser, 2007, Mekhail and Moazed, 2010). Interactions with components of the nuclear periphery such as lamins and inner nuclear membrane (INM) proteins have been suggested to be critical for peripheral localization (Mekhail and Moazed, 2010, Akhtar and Gasser, 2007). While several INM proteins are conserved from yeast to human, lamin proteins are absent in yeast, suggesting that proteins other than lamins may be critical for localization of heterochromatic domains to the nuclear periphery.

We developed a strategy for the isolation of fragmented, but otherwise native, heterochromatic and euchromatic DNA domains and analyzed their composition using quantitative mass spectrometry. We show that Swi6, which binds specifically to heterochromatic domains containing H3K9me (Nakayama et al., 2001, Bannister et al., 2001), and Bdf1 and Bdf2, bromodomain proteins, which bind to acetylated histones in euchromatin (Garabedian et al., 2012), can be used to isolate native heterochromatin and euchromatin, respectively. The Swi6-associated heterochromatin proteome contains nearly all of the proteins that have been previously identified with roles in heterochromatin formation in S. pombe, while the Bdf1- and Bdf2-associated proteomes bear signatures of transcriptionally active euchromatin, but also contain factors that overlap with the heterochromatin proteome, suggesting that specific as well as common proteins are associated with each type of chromatin domain. In addition, several nuclear pore complex (NPC) subunits and inner nuclear membrane (INM) protein are specifically enriched in Swi6 heterochromatin, and here we explore the roles of these proteins in epigenetic inheritance and subnuclear organization of H3K9me-associated chromatin.

Results

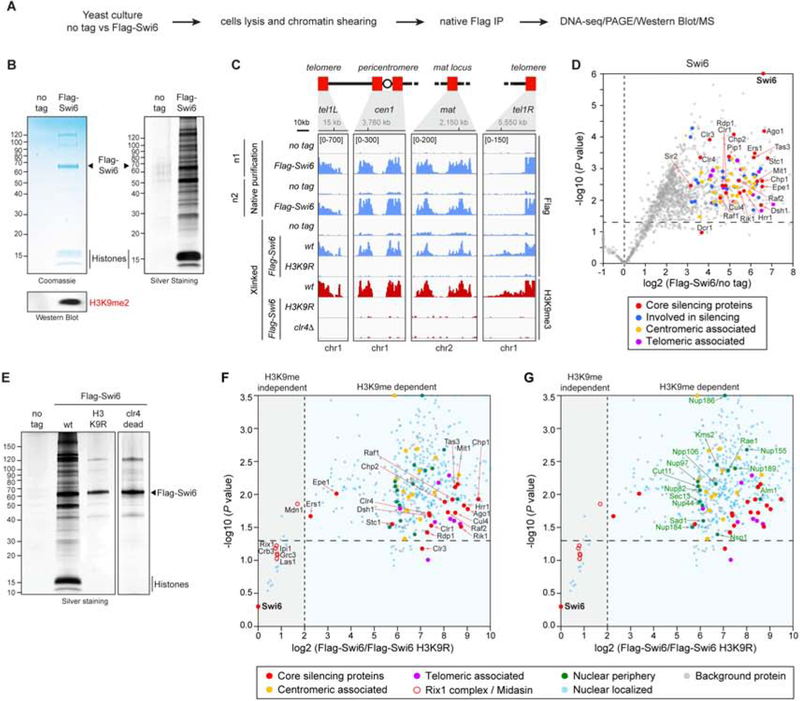

A strategy for isolation of native chromatin domains

To gain insight into the composition of heterochromatin, we tested whether heterochromatic DNA fragments could be purified through their specific association with nucleosome binding proteins. Swi6 and Chp2 are the fission yeast HP1 homologs that exclusively associate with nucleosomes containing H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 in heterochromatic DNA domains (Sadaie et al., 2008, Jih et al., 2017, Nakayama et al., 2001). Because Swi6 is approximately 20-fold more abundant than Chp2 (Sadaie et al., 2008), we constructed S. pombe cells that express a fully functional endogenous Flag-Swi6 protein to perform these studies. To generate an extract that contains soluble native chromatin fragments, we sheared DNA during cell lysis with glass beads or by subsequent sonication in a buffer with physiological ionic strength, and used the soluble fraction for a one-step Flag immunoprecipitation (Figure 1A, see Experimental Procedures for details). In contrast to the more stringent two-step tandem affinity purification we used previously (Motamedi et al., 2008), this strategy should allow the isolation and identification of more labile interactions. Gel analysis of immunoprecipitations showed the expected 65 kDa band for Flag-Swi6 was specifically enriched in anti-Flag antibody immunoprecipitations from Flag-Swi6 but not the control extracts (Figure 1B). In addition to several other weakly staining bands, the Flag-Swi6 immunoprecipitates also specifically contained proteins in the size range of the core histones and were enriched for H3K9me (Figure 1B). To test whether Flag-Swi6 remained faithfully associated with heterochromatic DNA domains during cells lysis and purification, we extracted DNA from the immunoprecipitated material and used it for library construction and high throughput sequencing (native ChIP-seq, nChIP-seq). The Flag-Swi6 nChIP-seq localization patterns, from 2 independent purifications, closely mirrored Flag-Swi6 localization performed with standard crosslinked chromatin under stringent washing conditions and overlapped regions of histone H3K9me3 (Figure 1C, Figure S1A). Swi6 therefore remains specifically associated with its targeted heterochromatic DNA domains during our cell lysis and immune-purification process.

Figure 1. A strategy for isolation of native chromatin domains.

A, Outline of the strategy. B, Representative coomassie- (left) and silver-stained (right) SDS polyacrylamide gels showing proteins recovered by purification of 3×Flag-Swi6. Bottom, western blot showing that histones containing the heterochromatin mark, H3K9me2, were recovered using Flag-Swi6 nChIP. Molecular weight markers in kilodalton are shown on the left. C, Flag (blue) and H3K9me3 (red) ChIP-seq showing that Flag-Swi6 efficiently pulled-down every heterochromatin domain during native purifications. Native purification ChIP-seq (top four rows) and conventional ChIP-seq (Xlinked, crosslinked, bottom six rows) are shown. Reads mapped to different heterochromatin regions in the indicated genotypes are presented as reads per million (number in bracket in the first row of each ChIP-seq data). Top, chromosome coordinates. D, Volcano plot displaying the TMT-based quantitative MS result of Flag-Swi6 nChIPs. The plot shows log2 ratios of averaged peptide MS intensities between Flag-Swi6 and reference (no tag) eluate samples (x axis) plotted against the negative log10 P values (y axis) calculated across the triplicate datasets (one-tailed Student’s t test, n = 3 biological replicates). Note maximum upper values were set for the x and y axis to accommodate all detected proteins in the plot. A dashed horizontal black line marks the P value = 0.05. Major Flag-Swi6 pulled-down protein groups relevant for this study are color coded as indicated and selected protein names are denoted. The full dataset of specific co-precipitating proteins is given in Table S1. E, Silver-stained SDS polyacrylamide gels showing proteins recovered by purification of Flag-Swi6 in the indicated mutant backgrounds. F, Volcano plot displaying the label-free MS result of Flag-Swi6 nChIPs plotted as in (D) against the reference (Flag-Swi6 nChIP in a H3K9R mutant background). Dashed black lines mark the P value = 0.05 (horizontal) and an enrichment of 4-fold compared to the reference (vertical). Major Flag-Swi6 pulled-down protein groups relevant for this study are color coded as indicated, and selected protein names are denoted. Note maximum upper values were set of the x and y axis to accommodate all detected proteins in the plot. n = 3 biological replicates. The full data set of specific co-precipitating proteins is given in Table S2. G, same as (F) but showing the nuclear periphery proteins pulled-down in Flag-Swi6 nChIPs. See also Figure S1.

Quantitative mass spectrometry analysis of Swi6 heterochromatin

We next performed immunoprecipitations from no tag control and Flag-Swi6 cells in triplicates and analyzed the samples by isobaric tandem mass tag-based quantitative mass spectrometry (TMT-MS)(Navarrete-Perea et al., 2018). We plotted the proteins that were enriched in Flag-Swi6 over no tag pulldowns versus p values calculated based on relative enrichment (Figure 1D, see color code). Together with many general chromatin proteins, nearly all of the previously identified heterochromatin-associated factors were highly enriched in the Flag-Swi6 pulldowns (Figure 1D, denoted by red circles). In addition, components of the centromere/kinetochore and telomeres (Pidoux and Allshire, 2004, Nandakumar and Cech, 2013), which are associated with DNA domains that abut heterochromatin, were greatly enriched in the Flag-Swi6 pulldown (Figure 1D, yellow and purple circles, respectively). Native Swi6 pulldowns can therefore be used to identify heterochromatic chromosome fragments and their associated proteins.

Swi6 purifications may contain heterochromatin-associated factors that require H3K9me for their association with Swi6 as well as factors that interact with Swi6 directly independently of H3K9me. To test this hypothesis, we performed Flag-Swi6 purifications from cells in which all three copies of genes encoding histone H3 carried lysine to arginine substitutions at position 9 (H3K9R) or expressed a catalytically dead Clr4 enzyme (Figure 1E). As expected, H3K9R substitutions abolished the association of Swi6 with heterochromatic domains to the background level observed in clr4Δ cells (Figure 1C). Furthermore, silver staining showed that the association of most proteins with Flag-Swi6 depended on H3K9me (Figure 1E). Consistently, MS analysis indicated that the association of centromeric and telomeric proteins, RITS subunits (Chp1, Ago1, Tas3), RNA-dependent RNA polymerase complex subunits (Rdp1, Hrr1), other RNAi proteins (Ers1, Dsh1, Stc1), CLRC subunits (Clr4, Raf1, Raf2, Rik1, Cul4), SHREC subunits (Clr1, Clr3, Mit1), the putative histone demethylase Epe1, and the other HP1 protein, Chp2, with Flag-Swi6 was H3K9me-dependent (Figure 1F; Figure S1B). In contrast, subunits of the Rix1 complex, an RNA processing complex localized to heterochromatin and previously shown to interact with Swi6 (Figure S1C)(Kitano et al., 2011), associated with Flag-Swi6 in an H3K9me-independent manner, suggesting that this complex binds to Swi6 directly (Figure 1F; Figure S1B). The identification of many previously identified silencing factors and proteins associated with heterochromatin or chromatin domains that border it validates native Swi6 immunoprecipitation as a strategy for the isolation and proteomic analysis of heterochromatic DNA fragments.

In addition to known silencing proteins, Flag-Swi6 pulldowns contained other chromatin proteins (Figure 1D–F; Table S1 and S2). The most notable among these were proteins associated with the nuclear periphery, including subunits of the NPC and nuclear envelope proteins (Figure 1G; Table S1 and S2). The latter included the SUN domain protein Sad1 and the KASH domain protein Kms2, which connect the inner and outer nuclear membranes and are required for insertion of the spindle pole body (SBP) into the nuclear envelop (King et al., 2008). The NPC proteins associated with Flag-Swi6 included the inner nuclear membrane protein Cut11/NDC1 and the Npp106/Nic96 subcomplex (Figure 1G). Except for Nup40, which was not retrieved in our purification, every subunit of the Npp106/Nic96 inner ring subcomplex (Nup97, Npp106, Nup155, Nup184, Nup186), which interacts with Cut11 and mediates NPC assembly (Knockenhauer and Schwartz, 2016), was associated with Flag-Swi6 in an H3K9me-dependent manner (Figure 1G; Figure S1D). In addition, two inner channel phenylalanine/Glycine (FG) nucleoporins (Nsp1 and Nup44) and Nup82, a cytoplasmic nucleoporin that associates with the FG nucleoporins (Knockenhauer and Schwartz, 2016), were enriched in the Flag-Swi6 purifications (Figure 1G; Figure S1D). These findings identify the nuclear envelope and a specific subset of nucleoporins as Swi6- and heterochromatin-associated factors.

We also used nChIP and mass spectrometry to analyze heterochromatin composition in the fission yeast S. japonicus, which diverged from S. pombe approximately 30 million years ago (Rhind et al., 2011). The results showed that the S. japonicus heterochromatin proteome contains nearly the same specific sets of proteins as the S. pombe heterochromatin proteome, providing further evidence for the robustness and reproducibility of our approach (Figure S1E–G).

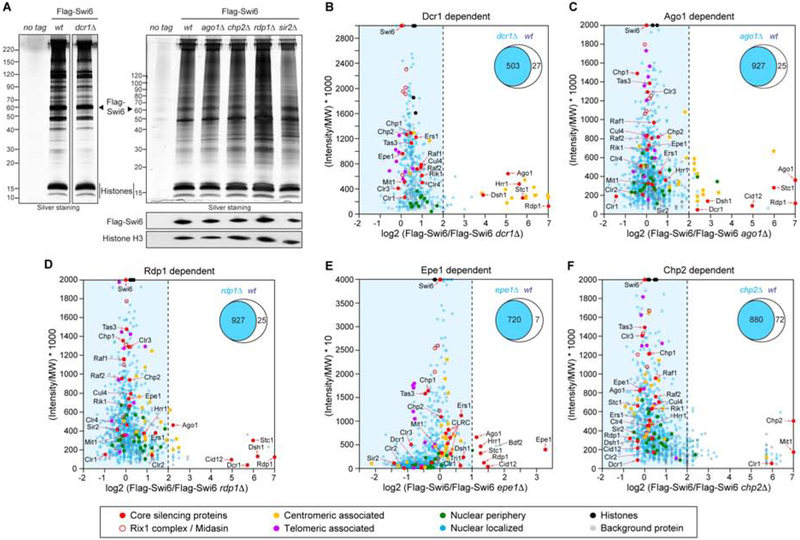

In an attempt to identify proteins specifically associated with different heterochromatic regions, we purified Flag-Swi6 from cells with mutations that disrupt heterochromatin formation at different chromosomal locations (Figure 2A; Figure S2). ChIP-seq analysis of H3K9me3 and Flag-Swi6 verified the expected loss of heterochromatin at pericentromeric DNA repeats in cells lacking the ribonuclease Dicer (dcr1Δ) (Volpe et al., 2002), reduced heterochromatin formation at telomeric DNA regions in cells that lacked both Dcr1 and the telomere-binding protein Taz1 (dcr1Δtaz1Δ)(Kanoh et al., 2005), and intact heterochromatin in both mutant backgrounds at the mating type (mat) locus (Figure S2A). Swi6 nChIP-MS analysis in dcr1Δ cells revealed a specific loss of proteins associated with the core centromere (yellow filled circles), the RNAi proteins Ago1, Rdp1, Hrr1, and Dsh1 as well as the adaptor protein Stc1, which links RNAi to the CLRC methyltransferase complex (Figure 2B; Figure S2B, S2E, Table S2) (Bayne et al., 2010). In contrast, the association of many other heterochromatin proteins that can associate with H3K9me domains independent of siRNAs (Sadaie et al., 2004, Debeauchamp et al., 2008), such as Chp1, Chp2, Tas3, and subunits of the CLRC and SHREC complexes was reduced but not eliminated in dcr1Δ cells (Figure 2B; Figure S2B, S2E–F, Table S2). The subsequent deletion of taz1+ in dcr1Δ cells (dcr1Δtaz1Δ), resulted in further reduced association of CLRC subunits, as well as reduced association of Rap1 and to a lesser extent other telomeric proteins (Poz1, Tpz1) with Flag-Swi6-associated chromatin (Figure S2C, S2E–F, Table S2). However, the association of Cut11 and the Npp106 subcomplex with Swi6 was only weakly reduced in dcr1Δ and dcr1Δtaz1Δ mutant cells (Figure 2B–F, green circles; Figure S2EG, Table S2), suggesting that heterochromatin remained associated with Cut11/Npp106 regardless of the mechanism of establishment. Similarly to dcr1Δ cells, the association of both centromeric proteins and RNAi factors with Flag-Swi6 was greatly reduced in ago1Δ and rdp1Δ cells (Figure 2C and D, Table S2). Notably, as expected from its siRNA-dependent association with Tas3 and chromatin (Holoch and Moazed, 2015b), the association of Ago1 with heterochromatin was greatly reduced in dcr1Δ cells, but the extent of the reduction was much smaller in rdp1Δ compared to dcr1Δ cells (Figure 2C, D, Table S2). This observation is consistent with previous detection of Rdp1-independent Dcr1-produced siRNAs (Halic and Moazed, 2010), and highlights the sensitivity of our native chromatin analysis relative to crosslink-based ChIP approaches. Additionally, consistent with the role of Epe1 in transcription-dependent localization of RNAi to pericentromeric DNA repeats (Zofall and Grewal, 2006), the association of Ago1, Stc1, and subunits of the RDRC complex with Flag-Swi6 heterochromatin was partially Epe1-dependent (Figure 2F, Table S2).

Figure 2. Identification of proteins specifically associated with different types of heterochromatin.

A, Representative silver-stained SDS polyacrylamide gels showing proteins recovered by purification of Flag-Swi6 in wild-type (wt) and dcr1Δ cells. B-F, label-free MS (B-E) and TMT-based quantitative MS (F) experiments plotted by relative protein abundance (total peptide intensity divided by molecular weight [MW] multiplied by a 1000 (B-E) or 10 (F)) on the x axis and log2 ratio (intensity of peptides originating from the Flag-Swi6 versus Flag-Swi6 mutant background IP) on the y axis. Note maximum upper values were set on the x and y axis to accommodate all detected proteins in the plot. A dashed vertical line marks a fold enrichment = 4 (B-E) or 2 (F) compared to the reference. Venn diagrams (top right) denote the number of proteins common (blue) or enriched (white) in the Flag-Swi6 wt versus mutant background IP, left or right of the dashed vertical line, respectively. Major Flag-Swi6 pulled-down protein groups relevant for this study are color coded as indicated, and selected protein names are denoted. n = 1 (C-E) or 3 (B, F) biological replicates. The full data set of specific co-precipitating proteins is given in Table S2. See also Figure S2.

Previous studies suggest that the main contribution of the less abundant fission yeast HP1 protein, Chp2, to heterochromatic silencing involves recruitment of the Clr3 histone deacetylase (HDAC) complex, SHREC, which also contains Clr1, Clr2, and Mit1 (Motamedi et al., 2008). Analysis of the heterochromatin proteome in chp2Δ cells showed that only the association of the Mit1 and Clr1 subunits of SHREC, but not Clr2 and Clr3, with Flag-Swi6 heterochromatin was Chp2-dependent, suggesting the presence of a Chp2-dependent subcomplex that contains Clr1 and Mit1 but not the remaining subunits of the SHREC complex (Figure 2E, Table S2). This is consistent with previous findings showing that Clr1, Clr2, and Clr3, but not Mit1 or Chp2, are required for heterochromatin-dependent silencing at the mating type locus (Motamedi et al., 2008), and with the proposed Mit1/Chp2-independent recruitment of Clr3 to chromatin (Job et al., 2016). Finally, deletion of sir2+, which is required for efficient heterochromatin spreading (Shankaranarayana et al., 2003), did not affect the association of heterochromatin proteins with Flag-Swi6 (Figure S2D, Table S2).

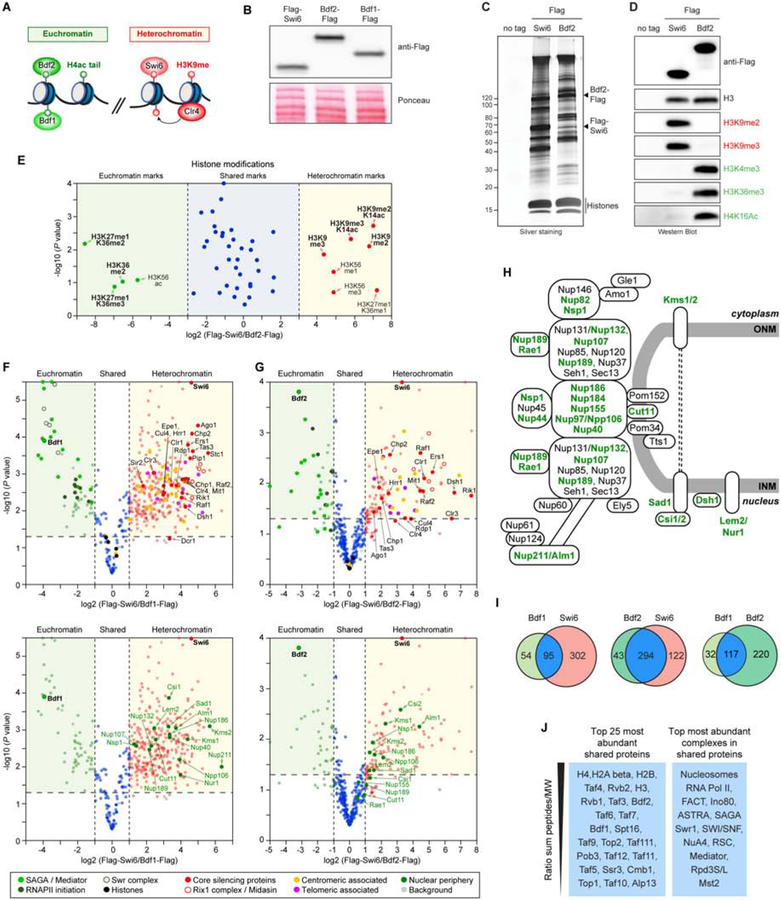

Heterochromatin versus euchromatin proteomes

To gain insight into heterochromatin- versus euchromatin-specific proteomes, we immunoprecipitated chromatin fragments bound to Bdf1 and Bdf2, highly conserved bromodomain proteins that associate with acetylated nucleosomes in transcriptionally active euchromatin (Matangkasombut and Buratowski, 2003, Garabedian et al., 2012, Durant and Pugh, 2007)(Figure 3A). As shown in Figure 3B, endogenously Flag-tagged Bdf1 and Bdf2 were expressed at similar levels as Flag-Swi6. Flag-Swi6 and Bdf2-Flag pulldowns were both associated with histones but otherwise co-precipitated subsets of proteins with distinct electrophoretic migration patterns (Figure 3C). Moreover, western blotting and MS showed that in contrast to Flag-Swi6, which was associated with H3K9me2 and H3K9me3, Bdf2-Flag was associated with histones bearing post-translational modifications of transcriptionally active euchromatin (H3K4me3, H3K36me3, and H4K16 acetylation)(Figure 3D, E; Figure S3A), demonstrating a high degree of specificity for our native chromatin isolation method. MS analysis of triplicate purifications of each Bdf1-Flag and Bdf2-Flag (either TMT-MS or label-free MS) and their comparison with Flag-Swi6 purifications identified domain-specific and shared proteins in each purification (Figure 3F, G; Figure S3B–E; Table S3). Notably, all of the known heterochromatin-associated proteins preferentially co-purified with Flag-Swi6 and were nearly absent in both Bdf1-Flag and Bdf2-Flag purifications (Figure 3F, G, top; Figure S3D, E). Similarly, Cut11 and subunits of the Npp106 subcomplex, as well as the inner nuclear basket nucleoporin, Nup211, preferentially associated with Flag-Swi6 but not Bdf1-Flag or Bdf2-Flag purifications (Figure 3F, G, bottom; Figure S3D, E). In addition to Cut11/Npp106, this comparison revealed that other nuclear membrane proteins, including Nur1, Lem2, Ksm1, Csi1, and Csi2, previously implicated in peripheral chromosome attachment (Mekhail et al., 2008, Barrales et al., 2016, Banday et al., 2016, Hou et al., 2013, Fernandez-Alvarez and Cooper, 2017, Costa et al., 2014), were also specifically enriched in the Flag-Swi6 proteome (Figure 3F, G, bottom, H). On the other hand, the main proteins enriched in Flag-Bdf1 and Bdf2-Flag were involved in transcription or its regulation. Subunits of the SAGA acetyltransferase complex and RNA polymerase II initiation factors were highly enriched in both Bdf1 and Bdf2 chromatin, but the SWR chromatin remodeling complex was preferentially associated with Bdf1 consistent with previous findings (Durant and Pugh, 2007)(Figure 3F, G, top). In addition to histones, a large number of other chromatin proteins were shared between Bdf1, Bdf2, and Swi6 proteomes, indicating that euchromatin and heterochromatin proteomes are not mutually exclusive (Figure 3I, J). In fact, the degree of overlap between Bdf1 and Bdf2 proteomes with each other and with the Swi6 proteome was similar (Figure 3I). Amongst the most notable proteins or complexes present in both heterochromatin and euchromatin proteomes were DNA topoisomerases I and II (Top1 and Top2), the origin recognition complex (ORC), RNA polymerase II (RNA Pol II) subunits, the cohesin complex (Rad21, Psc3), the Clr6-containing Rpd3 histone deacetylase complexes, and several chromatin remodeling complexes (Figure 3J). The presence of RNA Pol II in heterochromatin is consistent with its role in transcription of pericentromeric noncoding RNAs, which are required for RNAi-mediated heterochromatin formation.

Figure 3. Heterochromatin versus euchromatin proteomes.

A, Schematic of nucleosome-associated proteins used for isolation of native euchromatin (left) and heterochromatin (right) domains. B, Western blotting analysis showing that endogenous Flag-Swi6, Bdf1-Flag and Bdf2-Flag are expressed at similar levels. (C, D) Representative silver-stained SDS polyacrylamide gel (C) and western blot (D) showing that while Swi6 and Bdf1/2 pull-downs contained histones with heterochromatin- and euchromatin-associated modifications, respectively. E, Volcano plot displaying the MS analyses of the histone modification content in the immunoprecipitated chromatin fractions of Flag-Swi6 and Bdf2-Flag plotted as in (Figure 1D). n = 3 biological replicates. The full data set of specific histone modifications is given in Figure S3C. F, Volcano plot displaying the TMT-based quantitative MS result of Flag-Swi6 nChIPs plotted as in (Figure 1D) against Bdf1-Flag nChIPs. Dashed vertical lines mark a fold enrichment = 2 compared to the reference. The names of known heterochromatin proteins (top graph) and nuclear periphery proteins (bottom graph) are denoted. n = 3 biological replicates. The full dataset of specific co-precipitating proteins is presented in Table S3. G, same as (F) but showing the label-free MS analysis of protein content in the immunoprecipitated chromatin fractions of Flag-Swi6 versus Bdf2-Flag. n = 3 biological replicates. The full dataset of specific co-precipitating proteins is presented in Table S3. H, Diagram of known nuclear periphery proteins. Proteins in bold were present in the immunoprecipitated chromatin fraction by Flag-Swi6. I, Venn diagrams of full dataset from (F) and (G) showing the number of shared and specific proteins in the indicated immunoprecipitated chromatin fractions. J, Summary of the most abundant shared factors (left column) and complexes (right column) identified by MS in Flag-Swi6 IP versus Bdf1-Flag and Bdf2-Flag IPs. See also Figure S3.

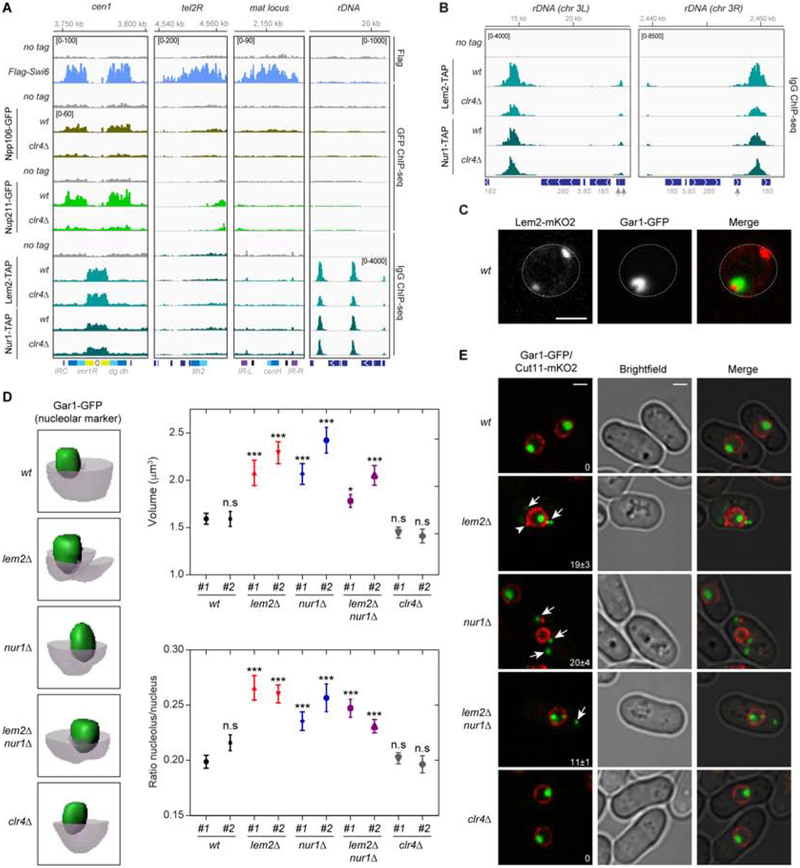

Interaction of nuclear membrane proteins with heterochromatic DNA domains

To determine the genome-wide localization of the nuclear periphery proteins specifically enriched in the Flag-Swi6 proteome (Figure 3H), we performed ChIP-seq experiments using endogenously tagged Npp106-GFP, Nup211-GFP, Lem2-TAP, and Nur1-TAP. Consistent with their co-purification with Swi6 chromatin, Npp106-GFP and Nup211-GFP displayed a similar, but weaker, pericentromeric localization pattern to that of Flag-Swi6 (Figure 4A). At telomeric DNA regions, the Npp106-GFP and Nup211-GFP ChIP-seq signals were only slightly above background, and Npp106-GFP, but not Nup211-GFP, weakly localized to the mat locus (Figure 4A). In contrast, consistent with previous results, Lem2-TAP and Nur1-TAP localized to the central core region of the centromere and the non-transcribed intergenic spacer region (IGS) of the rDNA repeats, but not to pericentromeric DNA repeats or other heterochromatic regions (Figure 4A, B)(Banday et al., 2016, Barrales et al., 2016). Consistent with the ChIP-seq results, we observed two Lem2-mKO2 fluorescent foci per nucleus, one of which co-localized with Gar1-GFP, which serves as a nucleolar marker (Figure 4C). Moreover, unlike Swi6, Npp106, or Nup211, the localization of Lem2 and Nur1 to target loci was largely Clr4-independent (Figure 1C; Figure 4A, B). The association of Lem2 and Nur1 with Flag-Swi6 chromatin is therefore likely to be indirect and mediated by chromatin fragments from regions that border heterochromatin and are expected to be present together with pericentromeric chromatin following DNA shearing.

Figure 4. Genome-wide localization of NPC and INM proteins and role for the Lem2 and Nur1 proteins in perinuclear anchoring.

A, ChIP-seq tracks showing the localization of the indicated proteins to representative heterochromatin domains. Reads are presented as reads per million (number in bracket). Top, chromosome coordinates. B, Same as in (A), but showing an expanded view of Lem2-TAP and Nur1-TAP ChIP-seq at rDNA regions. C, Representative images of live cells with Lem2-mKO2 and Gar1-GFP are shown. Dotted line indicates the nuclear periphery. Scale bar, 5 μm. D, Left, Representative 3D reconstructions of the nucleolus (green) and the nucleus (light gray). The nucleolus and nucleus were reconstructed based on the signals of the Gar1-GFP nucleolar marker and the Cut11-mKO2 nuclear membrane marker, respectively. Signal boundaries are shown with clipping planes for Cut11-mKO2. Right, top, the volume (μm3/y-axis) of the Gar1-GFP nucleolar domain plotted for the strains indicated in the x-axis. The average volume of n = 40–70 cells was calculated for each strain. Right, bottom, the ratio of the volume of the nucleolus to the volume of the nucleus plotted for the strains indicated in the x-axis. The average ratio of n = 40–70 cells was calculated for each cell separately and the averages from all cells were plotted for each strain. Error bars indicated SEM. P values of pairwise unpaired t-tests of each strain compared with the #1 wt strain are indicated with asterisks. n.s = not significant, *p<0.05, ***p<0.001. E, Images of live cells with Gar1-GFP nucleolar marker and Cut11-mKO2 nuclear membrane marker showing the fragmentation of the Gar1-GFP-stained nucleolus and its localization outside the nucleus in lem2Δ, nur1Δ, and double mutant cells (white arrows). White arrowhead highlights deformation of the nuclear envelop in lem2Δ cells. Percentage (%) of cells showing fragmentation is indicated (bottom right), calculated as the average ± s.d. from the two clones of each mutant strain. Scale bar, 2 μm. See also Figure S4.

Our quantitative MS analysis of Npp106-GFP purifications identified most components of the NPC, but no heterochromatin proteins (Figure S4A–C). The absence of heterochromatin proteins in these purifications is likely due to the greater abundance of NPCs (~150 per nucleus based on estimates in budding yeast)(Winey et al., 1997) relative to heterochromatin foci (<4 per nucleus) and the fact that only a small fraction of “specialized” NPCs or NPC subcomplexes may interact with heterochromatin. MS analysis of Lem2-TAP and Nur1-TAP identified the other protein as an interacting partner, as expected (Mekhail et al., 2008, Banday et al., 2016)(Figure S4D–F). In addition, Lem2-TAP purifications, and to a lesser extent Nur1-TAP purifications, were enriched for centromeric proteins and nucleoporins (Figure S4E–F). Co-purification of centromeric proteins with Lem2-TAP (and Nur1-TAP) is consistent with their localization to the central core region of the centromere. Together these findings suggest that the NPC and Lem2-Nur1 help anchor different chromosome regions, heterochromatin versus centromeres and rDNA, to the nuclear periphery.

Role for the Lem2 and Nur1 proteins in perinuclear anchoring

To address the possible role of Lem2-Nur1 at the rDNA repeats in fission yeast, we examined the localization of Cnp1-GFP and Gar1-GFP in wild-type, lem2Δ, nur1Δ, lem2Δnur1Δ, and clr4Δ cells in which the nuclear envelop was marked with Cut11-mKO2. Cnp1 is the fission yeast CENP-A homolog and serves as a reporter for centromere clustering and localization. Consistent with a previous report on lem2Δ cells (Barrales et al., 2016), we observed de-clustering of Cnp1-GFP in a subset of lem2Δ, nur1Δ and lem2Δnur1Δ mutant cells (Figure S4G, yellow arrows). Moreover, lem2Δ, nur1Δ, and lem2Δnur1Δ double mutant cells displayed an about 1.5-fold increase in the volume of the Gar1-GFP nucleolar marker (Figure 4D). More strikingly, a relatively large fraction of lem2Δ, nur1Δ, and lem2Δnur1Δ cells (~20%) had a fragmented nucleolus and contained foci of Gar1 staining outside the nucleus (Figure 4E, white arrows; Figure S4H). This result is consistent with the recent report that lem2Δ cells have impaired nuclear envelop assembly and display leakage of nuclear NLS-GFP into the cytoplasm (Kinugasa et al., 2019). In contrast, clr4Δ cells had wild-type nucleolar volume and did not display any nucleolar fragmentation (Figure 4D, E). These results indicate that Lem2 and Nur1, but not H3K9me, are required for nucleolar localization and integrity.

Npp106 is required for clustering of heterochromatin foci and epigenetic inheritance

The inner ring subcomplex subunits Npp106, Nup184, and Nup40 are not required for viability, but Nup97, the Npp106 paralog, and other subunits of the complex are essential. To begin to investigate whether the Npp106 subcomplex plays a role in heterochromatic gene silencing, we constructed npp106Δ cells and examined the effect of this deletion on heterochromatin formation and silencing. qRT-PCR analysis indicated that the pericentromeric dg, dh, the mat2P loci, and a ura4+ insert at the outer centromeric repeats (otr1R::ura4+), but not the telomeric tlh1 locus, were slightly derepressed in npp106Δ cells (Figure S5A). Consistently, npp106Δ cells had nearly wild-type levels of H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 at these loci (Figure S5B, C), but showed reduced spreading of H3K9me3 at the left telomere of chromosome 1 (tel1L, Figure S5D, red tracks). However, the association of Swi6 with pericentromeric dg and dh regions was reduced in npp106D cells, as indicated by ChIP-seq (Figure S5D, blue tracks) and ChIP-qPCR experiments (Figure S5E). The reduction in Swi6 association with pericentromeres was accompanied by increased spreading of Swi6 at subtelomeric DNA regions (Figure S5D, blue tracks). Moreover, in npp106D cells, histone H3K14 acetylation levels increased to levels comparable to clr4D cells, suggesting that the inner core nucleoporins play a critical role in recruitment of Clr3 or other deacetylases to heterochromatin (Figure S5F). These findings indicate that deletion of Npp106 affects the localization and relative distribution of Swi6 at different heterochromatic domains and impairs histone H3K14 deacetylation, in steps downstream of H3K9me.

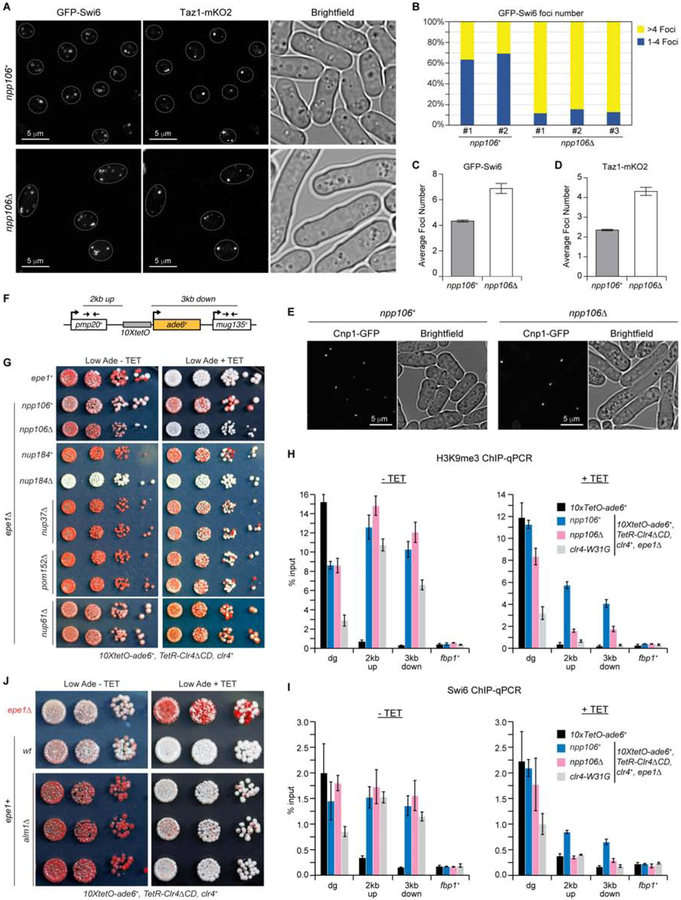

Since ChIP-seq data indicated that deletion of npp106+ causes Swi6 redistribution (Figure S5D, blue tracks), we investigated whether Npp106 played a role in the subnuclear localization of GFP-Swi6. In npp106+ cells, consistent with previous reports (Ekwall et al., 1995, Pidoux et al., 2000), GFP-Swi6 localized to a small number of foci, ranging from 1 to 4 in most cells (Figure 5A–C; Figure S5G). In npp106Δ cells, we observed a general increase in the number of Swi6 foci with a maximum of up to 8 foci in some cells (Figure 5A–C; Figure S5G). Moreover, relative to npp106+ cells, telomeres were de-clustered in npp106Δ cells as indicated by visualization of the telomere-binding protein Taz1 fused to mKO2 (Taz1-mKO2)(Figure 5A and D). In contrast, the deletion of npp106+ had little or no effect on Cnp1-GFP clustering (Figure 5E). We therefore conclude that Npp106 is required for the efficient clustering or aggregation of the non-centromeric heterochromatin regions (6 telomeres and the mat locus). Consistent with this conclusion, in some npp106Δ cells, we observed 8 foci of Swi6 staining, which would represent full de-clustering of non-centromeric heterochromatin (Figure 5A; Figure S5G).

Figure 5. Npp106 is required for clustering of heterochromatin foci and epigenetic inheritance.

A, Representative images of live cells with GFP-Swi6 and Taz1-mKO2. Dotted lines indicate the nuclear periphery. Scale bar, 5μm. B, Number of GFP-Swi6 foci is plotted as the percentage of cells with 1–4 foci (blue bar) or with more than 4 foci (yellow bars) for each strain (n = 200–300 cells). C, Average number of GFP-Swi6 foci (n = 2 biological replicates) for the indicated strains. D, Average number of Taz1-mKO2 foci (n = 2 biological replicates) for the indicated strains. E, Images of live cells with Cnp1-GFP centromeric marker in npp106+ and npp106Δ cells. Scale bar, 5μm. F, Map of 10XtetO-ade6+ reporter gene inserted in place of the ura4+ gene between pmp20+ and mug135+ genes. Thin arrows indicate primer locations for ChIP-qPCR analyses in H and I panels. G, Silencing assays of 10XtetO-ade6+ on low-adenine medium lacking tetracycline (Low Ade - TET) or containing tetracycline (Low Ade + TET) to assess heterochromatin establishment and maintenance, respectively, in TetR-Clr4DCD, clr4+ and epe1+ or epe1D cells containing the indicated NPC mutations. H, I, H3K9me3 (H) and Swi6 (I) ChIP-qPCR analyses of 10XtetO-ade6+ reporter gene and surrounding regions in cells with the above genotypes grown for 24 hr in the absence (-TET, left) or presence (+TET, right) of tetracycline. fbp1+, used as control, is a gene located in euchromatin. Values are shown as % input. Error bars, s.d.; n = 3 biological replicates. J, Silencing assays of 10XtetO-ade6+ showing that heterochromatin inheritance is enhanced in alm1Δ cells. 3 different alm1Δ isolates are presented. See also Figure S5.

We next tested whether Npp106 was required for epigenetic inheritance of heterochromatin using an ectopic heterochromatin formation assay that allows the establishment and epigenetic inheritance of heterochromatin to be separated (Ragunathan et al., 2015, Audergon et al., 2015). In the absence of tetracycline, the catalytic domain of Clr4 fused to the bacterial tetracycline repressor (TetR-Clr4ΔCD) is recruited to 10 tetracycline operators upstream of an ade6+ reporter gene (10XtetO-ade6+, Figure 5F) to establish heterochromatin, which leads to formation of colonies that turn red on medium lacking tetracycline (Low Ade -TET, Figure 5G, npp106+ left). Consistent with efficient establishment of heterochromatin at native loci (Figure S5), npp106Δ cells established 10XtetO-ade6+ silencing (Figure 5G, left). However, in contrast to npp106+ cells, 10XtetO-ade6+ silencing was lost in npp106Δ cells after tetracycline-induced release of TetR-Clr4ΔCD (Low Ade +TET), indicating that Npp106 was required for epigenetic inheritance of silencing (Figure 5G, right). Furthermore, Npp106 localized to the silenced 10XtetO-ade6+ locus (Figure S5H), and consistent with its requirement for maintenance of silencing, in npp106Δ cells grown on –TET medium, ChIP-qPCR experiments showed similar levels of H3K9me3 and Swi6 binding at the 10XtetO-ade6+ locus (Figure 5F, H, I; left panels) compared to npp106+, but both H3K9me3 and Swi6 binding were greatly diminished after 24 hours of growth on +TET medium (Figure 5F, H, I; right panels). As further controls and consistent with other results (Figure 5G), deletion of npp106+ had little or no effect on H3K9me3 and Swi6 levels at the centromeric dg repeats in cell grown on either –TET or +TET medium (Figure S5B, C), but a mutation in the Clr4 chromodomain (clr4–W31G), which disrupts its binding to H3K9me and is required for epigenetic inheritance (Ragunathan et al., 2015, Audergon et al., 2015, Jih et al., 2017), abolished H3K9me maintenance on +TET medium (Figure 5H, I). We conclude that Npp106 is required for epigenetic inheritance of H3K9me and silencing, by promoting heterochromatin clustering and/or histone H3K14 deacetylation.

We also tested a possible role in ectopic heterochromatin formation for other non-essential nucleoporins that were (Nup184, Nup40, Alm1) or were not (Pom152, Nup37, Nup61) associated with Swi6 chromatin (Fig 3H). Deletion of Nup184, a subunit of the Npp106 inner ring subcomplex, abolished establishment of TetR-Clr4-I-mediated silencing at the 10XtetO-ade6+ reporter locus (Figure 5G, left), but deletions of Nup40, another component of the inner ring complex, Pom152, an inner membrane protein thought to act in parallel with Cut11, or Nup37, a subunit of the outer ring, did not affect establishment or inheritance of silencing (Figure 5G, Figure S5I). Furthermore, deletion of t nup61+ or alm1+, which encode nuclear basket proteins, had little effect on establishment of 10XtetO-ade6+ silencing and, in the case of alm1Δ, allowed inheritance of silencing in a small fraction of epe1+ cells (Figure 5G, J). The silencing phenotypes resulting from deletion of nucleoporins are therefore largely restricted to components of the inner ring complex.

Discussion

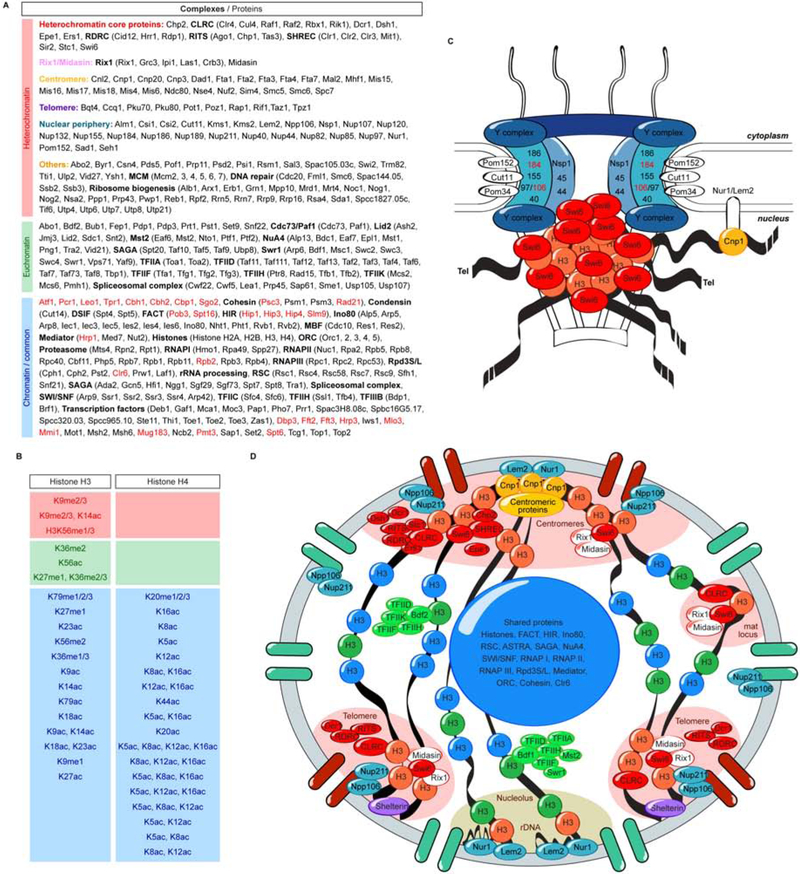

Our findings indicate that immunoprecipitation of native heterochromatin and euchromatin DNA fragments, without crosslinking, can be used to determine their protein composition. The proteomes defined by our studies are extensive and likely to represent the most comprehensive list of HP1 (Swi6) heterochromatin-associated proteins thus far reported. This is evidenced by the specific association of every key protein and every subunit of the complexes previously demonstrated to mediate heterochromatin formation in fission yeast, including all subunits of the RITS, RDRC, CLRC, and SHREC complexes, and the Dicer, Stc1, Chp2, Epe1, Sir2, Ers1, and Dsh1 proteins with Swi6 chromatin (Figure 6). Moreover, the specific association of a subset of nucleoporins with Swi6 heterochromatin allowed us to identify an unanticipated role for the Npp106 nucleoporin in clustering of multiple heterochromatic domains into a small number of foci and in epigenetic inheritance of H3K9me and silencing. Our results also suggest a role for the Lem2 and Nur1 INM proteins in perinuclear localization and integrity of the fission yeast nucleolus. Based on these findings and previous results, we propose that while the mechanisms that localize heterochromatin and other chromosome regions to the nuclear periphery appear to have diverged during evolution, the conserved core of H3K9me heterochromatin in eukaryotes from fission yeast to metazoans is composed of HP1 proteins, histone methyltransferase, and histone deacetylase complexes.

Figure 6. Summary of heterochromatin and euchromatin proteomes.

A, Summary of heterochromatin, euchromatin, and common chromatin complexes (in bold) identified by nChIP. Proteins in red in chromatin/shared are proteins that have been shown previously to be involved in silencing. B, Summary of histone modifications associated with euchromatin and heterochromatin. C, Model for nuclear pore complex (NPC)-mediated clustering of heterochromatic loci via interactions between Swi6 and the inner ring subcomplex. Centromeres are further associated with the periphery via interactions with the Nur1-Lem2 inner nuclear membrane complex. D, Diagram of the nucleus showing representative heterochromatin- and euchromatin-associated proteins and localization of specific chromosome regions to the nuclear periphery via interactions with Nur1-Lem2 or NPCs. The NPCs associated with heterochromatin are shown in red.

Native chromatin immunoprecipitation

The native chromatin immunoprecipitation approach used in our studies allows the isolation of chromatin domains based on their association with specific structural proteins. The specificity of our approach is evidenced by (1) nearly identical genome-wide Swi6 association patterns of native and standard formaldehyde crosslinked Swi6 immunoprecipitations and (2) the dependence of Swi6-associated proteins on histone H3K9me or other structural features of heterochromatin. nChIP should therefore be broadly applicable to analysis of other chromatin domains that are defined by binding of specific structural proteins, although comparison of bound genomic regions with and without crosslinking on a case-by-case basis is advisable to ensure that specific chromatin associations are preserved during native immunoprecipitation. Several other strategies have been used previously to define the composition of specific chromatin domains (Wang et al., 2013, Dejardin and Kingston, 2009, Becker et al., 2017, Zee et al., 2016). nChIP provides a complementary approach for the identification of proteins associated with specific chromatin domains, and with regards to heterochromatin, it appears to identify a more comprehensive list of heterochromatin-associated factors than previous approaches.

The heterochromatin proteome

Our findings highlight the association of four core machineries with S. pombe heterochromatin but not euchromatin: (1) RNAi proteins and complexes, (2) proteins involved in H3K9me binding, H3K9me, and histone deacetylation, (3) the Rix1 RNA processing complex, and (4) nuclear envelope proteins and nucleoporins. The first two groups have been described previously as associated with heterochromatin and play central roles in establishment and epigenetic maintenance of heterochromatic domains. The identification of nearly every previously described member of these two groups serves to validate the nChIP approach.

The third group of heterochromatin-associated proteins is defined by the Rix1 complex, which has been previously shown to localize to heterochromatic DNA domains, and is composed of Rix1, Grc3, Crb3, Las1, Ipi1, and Mdn1 (Midasin) (Kitano et al., 2011, Gasse et al., 2015, Castle et al., 2013). This complex is required for pre-rRNA processing and viability (Chen et al., 2018, Nissan et al., 2004). Its function in heterochromatic domains is unknown but hypomorphic viable alleles in the Grc3 subunit have defects in silencing of centromeric dh transcripts and a reporter genes inserted at pericentromeric DNA repeats (Kitano et al., 2011). Our study shows that subunits of the Rix1 complex represent the most abundant group of proteins associated with Swi6, interacts with Swi6 in an H3K9me-independent manner, and display the same genomic localization pattern as Swi6, suggesting that they play important roles in heterochromatin function.

The fourth group of proteins specifically associated with Swi6 chromatin are subsets of nucleoporins and inner nuclear membrane proteins. The INM proteins, Lem2 and Nur1, have been implicated previously in heterochromatin function in S. pombe and S. cerevisiae (Mekhail et al., 2008, Barrales et al., 2016, Banday et al., 2016). Our results suggest that in S. pombe these proteins largely interact with the rDNA repeats and heterochromatin-proximal centromeres, rather than heterochromatin-proper. At the centromeres, the Lem2-Nur1 complex is likely to act together with several other INM proteins that co-purify with Swi6 heterochromatin (this study) and have been shown to localize to centromeres (Hou et al., 2013). The nucleoporins represent a new class of heterochromatin-associated factors and will be discussed in more detail below.

Our purifications also uncover a number of other proteins that are either specifically enriched in heterochromatin or are shared between heterochromatin and euchromatin proteomes (Figure 6; Tables S1–S3). The shared proteins include the Atf1/Pcr1 heterodimer and the Clr6 histone deacetylase complex, which are known to be involved in heterochromatin formation (Jia et al., 2004, Grewal et al., 1998). Other factors in these groups are therefore candidates with potential roles in heterochromatin assembly or function. Comparison of heterochromatin-associated factors identified by nChIP to those identified in previous studies in Drosophila and human suggests that the conserved core of heterochromatin is composed of one or more of the Su(var)3–9 family H3K9 methyltransferases (S. pombe Clr4, Drosophila Su(var)3–9 and Egg/dSetdb1, and human SUV39H1 and H2), a histone deacetylase (S. pombe Clr3, Drosophila HDAC3, and human HDAC2), and HP1 proteins (S. pombe Swi6 and Chp2, Drosophila HP1a and HP1b, and human HP1α and HP1β)(Swenson et al., 2016, Alekseyenko et al., 2014, Becker et al., 2017).

Roles for inner nuclear membrane proteins and nucleoporins in chromatin organization

Heterochromatic domains assemble into a limited number of foci that are localized to the nuclear periphery (Ekwall et al., 1995, Cabianca and Gasser, 2016). Each focus appears to form by clustering of several distinct heterochromatic DNA regions. In S. pombe, a total of 10 different heterochromatic regions, localized on 3 different chromosomes (3 pericentromeric, 6 telomeric, and 1 mating type), cluster into an average of 4 foci per nucleus (Ekwall et al., 1995, Pidoux et al., 2000). In addition to these loci, the rDNA repeats, which constitute the most repetitive regions of the fission yeast genome, require heterochromatin factors for their stability and are localized to the nuclear periphery. Our findings suggest that distinct mechanisms involving INM proteins and nucleoporins mediate the clustering and localization of each of the above domains to the nuclear periphery.

Our ChIP-seq analysis indicates that the INM proteins, Lem2 and Nur1, localize primarily to the central core regions of centromeres, which lack H3K9me and Swi6, and the rDNA repeats, which contain low levels of H3K9me (Shankaranarayana et al., 2003). Their association with Swi6 chromatin is therefore likely to reflect the proximity of the centromere and the heterochromatic pericentromeric DNA regions. S. pombe centromeres cluster together at the nuclear periphery. Deletion of Lem2 or Nur1 results in partial de-clustering of the centromeres (Barrales et al., 2016) and also disrupts the perinuclear localization and integrity of the nucleolus (this study, Figure 4). Their roles in rDNA tethering and nucleolar integrity appears to be conserved between budding and fission yeasts (this study)(Mekhail et al., 2008). The presence of the nucleolar marker Gar1-GFP outside of the nucleolus in lem2Δ and nur1Δ cells may be related to the recently described phenomenon of nucleophagy (Mostofa et al., 2018) or the requirement for these proteins in promoting the sealing of the nuclear envelop after mitosis (Gu et al., 2017, Kinugasa et al., 2019). In mammalian cells, the LEM domain proteins, Lap2, Man1, and Emerin are enriched at H3K9me domains, but neither the nucleoli or centromeres attach to the INM and have not been reported to interact with LEM domain proteins. The LEM domain proteins therefore appear to perform a conserved function in perinuclear tethering of chromatin domains, but seem to tether different types of domains in different species.

Our results also reveal that a subset of nucleoporins, primarily involving the Npp106 (Nic96 in S. cerevisiae, Nup93 in Drosophila and mammals) subcomplex, specifically interact with heterochromatin, and that Npp106 is required for peripheral clustering and epigenetic inheritance of S. pombe heterochromatin. The Npp106 subcomplex associates with the inner nuclear membrane protein Cut11 (human NDC1) and forms an inner ring that serves as a structural scaffold for the nuclear pore complex (NPC) (Knockenhauer and Schwartz, 2016). In addition, subunits of the Npp106 complex have been implicated in chromatin-related functions. The transmembrane protein Cut11 has been implicated in proper insertion of the spindle pole body, the fission yeast equivalent of the centrosome, into the inner nuclear membrane, and the budding yeast inner ring protein Nup170 (S. pombe Nup155) was reported to interact with the silencing protein Sir4 and help localize telomeres to the nuclear periphery (Van de Vosse et al., 2013, West et al., 1998, Lapetina et al., 2017). The human homolog of Npp106, NUP93, has been suggested to associate with superenhancers and localize them to the nuclear periphery (Ibarra et al., 2016), and to the HOXA cluster to mediate silencing (Labade et al., 2016). Furthermore, in Drosophila, distinct NPC subunits were found to associate with transcriptionally active and silent genomic regions, suggesting roles for different NPC subunits in gene activation and silencing (Capelson and Hetzer, 2009). The effects of nucleoporin mutations or knockdowns on chromatin are difficult to uncouple from possible indirect effects related to nuclear transport. In S. pombe, the specific association of nucleoporins with heterochromatin combined with the specific loss of H3K9me epigenetic inheritance in npp106Δ cells argues that nucleoporin-heterochromatin interactions are functionally important. Whether this possible function involves only the Npp106 inner ring complex or the entire NPC remains to be investigated.

In addition to Npp106, our experiments identified Nup211 and several other non-inner ring and FG-repeat central channel nucleoporins as heterochromatin-associated. Unlike Npp106, Nup211 and central channel proteins are required for viability, but the weak increase in efficiency of heterochromatin inheritance in cells carrying deletions of other non-essential basket proteins, such as Alm1 and Nup61, suggests that the basket proteins may restrict heterochromatin access to inner ring components. An intriguing possibility is that the inner ring of NPC promotes the clustering of several distal heterochromatin domains either by providing a surface for multivalent interactions or by facilitating the proposed HP1/Swi6-driven phase transition into liquid droplets (Larson et al., 2017, Strom et al., 2017)(Figure 6C). Our findings, together with a study by Capelson and colleagues (Gozalo et al., Submitted), which reports a role for Nup93, the Drosophila homolog of S. pombe Npp106, in silencing and clustering of Polycomb-targeted loci, and previous findings in budding yeast (Lapetina et al., 2017), suggest a conserved role for the inner ring subcomplex of the NPC in organization and function of silent chromatin domains.

STAR Methods

Lead Contact and Materials Availability

Further information and requests for reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Danesh Moazed (danesh@hms.harvard.edu). The materials generated in this study would be shared without restriction.

Experimental Model and Subject Details

Strain construction

S. pombe strains used in this study and their genotypes are listed in Table S5. All strains except SPY9673 and SPY9674 were constructed by transformation using a PCR-based targeting method and lithium acetate protocol (Bahler et al., 1998) and selected on yeast extract plus adenine (YEA) plates that contained appropriate antibiotic. SPY9673 and SPY9674 strains were constructed by crossing SPY5090 and SPY8064 followed by random spore analysis. Integrations were confirmed by colony PCR. All tagged genes were expressed under the control of their endogenous promoters and terminators.

Method Details

Silencing assays

Cells were grown at 30 °C overnight in 5 ml of YEA medium. 1 × 107 cells were collected, washed once with sterile water, suspended in 200 μl of sterile water, and then serially diluted tenfold. Three microlitres of each dilution was spotted on the appropriate growth medium. Tetracycline was used at a concentration of 5 μg/ml. Plates were incubated at 32 °C for 3–5 days. Silencing of the ade6+ reporter gene was assessed by growth on yeast extract (YE) plates that were additionally incubated at 4 °C for 1–2 days to enhance the red pigmentation before imaging.

Protein analysis

Samples were loaded on 4–20% gradient TGX Gels (Biorad). Coomassie staining was performed with Novex™ SimplyBlue™ SafeStain (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Silver staining was performed with Silver Stain SNAP Kit (Pierce) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The primary antibodies used for western blot analyses were anti-Flag HRP-conjugated (Sigma A8592), anti-GFP HRP-conjugated (Fisher Scientific MA5–15256-HRP), anti-H3K9me2 (Abcam 1220), anti-H3K9me3 (Active Motif 61013), anti-H3 (Abcam 1791), anti-H3K4me3 (Abcam 8580), anti-H3K36me3 (Abcam 9050), and anti-H4K16ac (Active Motif 39167).

Affinity purification for LC–MS/MS

For heterochromatin purification using Flag–Swi6, one liter of wild-type or mutant cells expressing 3 × Flag–Swi6 under its endogenous promoter were grown in exponential phase to a density of 3 × 107 cells/ml at 32°C in yeast extract medium with supplements (YES), harvested by centrifugation, transferred to a 50 ml tube, washed twice in TBS (50 mM Tris (pH 7.6), 150 mM NaCl), and frozen at −80 °C (approximately 1.5–2 g of cells). All subsequent steps were performed at 4 °C. The frozen cells were resuspended in one volume of ice-cold lysis/IP buffer (20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 0.5 mM DTT, 10% glycerol, 0.25% Triton X-100, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche)) and lysed by glass-bead beating 6 times for 45 s at 5,000 r.p.m. with 1 ml of 0.5 mm glass beads per 800 μl of yeast resuspension (MagNa Lyser, Roche). To keep the samples cold throughout cell lysis and reduce protein degradation, samples were placed 1 min on ice in between each glass-bead beating cycle. Tubes were punctured and the crude lysate was collected in a fresh tube by centrifugation. After two consecutive rounds of centrifugation at 12,000 g for 3 min and 15 min, respectively, the cleared lysates were pooled and diluted to a protein concentration of 25 mg/ml with ice-cold lysis buffer. For each sample, 225 μL of prewashed Protein G Dynabeads (Life Technologies) were incubated with 57 g of α-FLAG (F1804, Sigma) antibody overnight at 4 °C. Antibodies were cross-linked to the beads using 19 mM dimethyl pimelimidate (Pierce) in 10 bead volumes of 0.2 M sodium borate, pH 9. Crosslinking was allowed to proceed for 30 min at room temperature and was quenched by the addition of 0.2 M ethanolamine, pH 8. Beads were washed twice with 10 bead volumes of IP buffer and resuspended in 1 bead volume of IP buffer before adding to cell extracts and incubating at 4 °C for 3 hrs. The beads were collected on magnetic stands, and washed three times with 1 ml ice cold IP buffer followed by one 5-min wash at 4 °C. Proteins were eluted in 2.5 bead volume of 500 mM NH4OH at 37 °C for 20 min and samples were dried overnight using a SpeedVac concentrator. Five percent of eluted proteins were analyzed by silver staining and 2.5% of eluted proteins were analyzed by western blotting. The remainder of the eluted protein was analyzed by mass spectrometry.

For heterochromatin versus euchromatin purifications using Flag–Swi6 and Bdf1-Flag or Bdf2-Flag, respectively, three liters of wild-type cells expressing 3 × Flag–Swi6, Bdf1–3 × Flag, and Bdf2–3 × Flag under their endogenous promoter were grown in exponential phase to a density of 3 × 107 cells/ml at 32°C in yeast extract medium with supplements (YES) and harvested by centrifugation. Extracts were prepared based on the method described (Oeffinger et al., 2007) using a freezer-mill (Freezer/Mill 6875, SPEX SamplePrep). A freezer-mill was used instead of bead beating to break the cells because both Bdf1 and Bdf2 were sensitive to degradation when using bead beating. Cell pellets were resuspended in a volume of ice-cold lysis/IP buffer equal to one-fifth of the pellet volume then added dropwise to liquid nitrogen. Cells were lysed by ten cycles of cryo-milling for 2 min each, 1 min rest, at 10 cycles per second in a SPEX SamplePrep Freezer/Mill 6875. Yeast powder was resuspended in a volume of ice-cold lysis/IP buffer equal to one volume of the pellet and centrifuged twice at 12,000 g for 3 min and 15 min, respectively. The cleared lysates were diluted to a protein concentration of 25 mg/ml with ice-cold lysis buffer, sonicated at 66%, 6 sec ON, 1 min OFF for 1 min total sonication in metal buckets and incubated with 540 L of Protein G Dynabeads (Life Technologies) cross-linked with 132 L of anti-Flag (Sigma F1804) antibody for 4 hrs at 4 °C. Beads were washed and proteins were eluted as described above. Eight percent of eluted proteins were analyzed by silver staining and 1% of eluted proteins were analyzed by western blotting. The remaining 90% of the eluted protein was analyzed by mass spectrometry.

For heterochromatin purification using S. japonicus Flag–Swi6, three liters of wild-type cells expressing 3 × Flag–Swi6 under its endogenous promoter were grown in exponential phase to a density of 2 × 107 cells/ml at 30°C in yeast extract medium supplemented with adenine (YEA) and harvested by centrifugation. Extracts and purifications were performed as described above for heterochromatin versus euchromatin purification.

For Npp106-GFP purifications, extracts and purifications were performed as described for heterochromatin purification using Flag–Swi6 with 1L of cells using a MagNa Lyser, except for the following modifications. The frozen cells were resuspended in one volume of ice-cold lysis/IP buffer 2 (12 mM Na2HPO4, 8 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 4 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 2 mM EGTA (pH 8.0), 40 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.2% NP-40, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche)) and lysed by glass-bead beating in MagNa Lyser 5 times for 45 s at 5,000 r.p.m. with 1 ml of 0.5 mm glass beads per 800 μl of suspended yeast cells. After two consecutive rounds of centrifugation at 12,000 g for 3 min and 15 min, respectively, the cleared lysates were pooled and diluted to a protein concentration of 25 mg/ml with ice-cold lysis buffer. For each sample, 120 μL of prewashed Protein A Dynabeads (Life Technologies) crosslinked, as described above, with 20 μg of α-GFP (Ab290, Abcam), were incubated for 2 hrs at 4 °C. The beads were collected on magnetic stands, and washed three times with 1 ml ice cold wash buffer (10 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP-40, 1 mM DTT, complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche)) followed by one 5-min wash at 4 °C. Proteins were eluted in 4 bead volume of 500 mM NH4OH at 37 °C for 20 min and samples were dried overnight using a SpeedVac concentrator. Eight percent of eluted proteins were analyzed by silver staining and 1% of eluted proteins were analyzed by western blotting. The remainder of the eluted protein was analyzed by mass spectrometry.

For Lem2-TAP and Nur1-TAP purifications, extracts and purifications were performed as described for heterochromatin versus euchromatin purifications with 3L of cells using a freezer-mill, except for the following modifications. Yeast powder was resuspended in a volume of ice-cold lysis/IP buffer equal to 2.55 volume of the pellet and centrifuged twice at 12,000 g for 3 min and 15 min, respectively. The cleared lysates were diluted to a protein concentration of 25 mg/ml with ice-cold lysis buffer, sonicated at 50%, 20 sec ON, 1 min OFF for 1 min total sonication (Branson Sonifier Digital Cell Disruptor, Model S-450D with microtip, Branson Ultrasonics) in metal buckets and incubated with 300 μL of IgG Pan Mouse Dynabeads (Invitrogen) for 4 hrs at 4 °C. Beads were washed and proteins were eluted as described above. Eight percent of eluted proteins were analyzed by silver staining and 1% of eluted proteins were analyzed by western blotting. The remaining 90% of the eluted protein was analyzed by mass spectrometry.

Label-free sample preparation and mass spectrometry analysis

Label-free mass spectrometry analysis was performed using either GeLC-MS/MS or in solution digestion, as specified in the main text. The GeLC-MS/MS analysis was performed as described previously (Paulo, 2016). Gel bands were excised and their protein content was digested in-gel with trypsin (Shevchenko et al., 2006, Shevchenko et al., 1996). The extracted peptides were desalted via StageTip, dried via vacuum centrifugation, and reconstituted in 5% acetonitrile, 5% formic acid for LC-MS/MS processing. In solution digestion was performed on beads from immunoprecipitations or upon eluting proteins from the beads. Proteins were reduced with DTT or TCEP and alkylated with iodoacetamide, and digested with LysC and trypsin. Peptides were subjected to SPE before being analyzed by mass spectrometry (Haas et al., 2006, Edwards and Haas, 2016).

Label-free mass spectrometry data were collected using microcapillary liquid chromatography mass spectrometry on Q Exactive, Orbitrap Elite, and Orbitrap Fusion mass spectrometers (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA) essentially as described previously (Huttlin et al., 2015, Haas et al., 2006, Minajigi et al., 2015).

Analysis of mass spectrometry data.

Mass spectra were processed using a Sequest-based in-house software pipeline. MS spectra were converted to mzXML using a modified version of ReAdW.exe. Database searching included all entries from the Schizosaccharomyces pombe (downloaded: November 11, 2017) or Schizosaccharomyces japonicus (downloaded: November 11, 2017), which was concatenated with a reverse database composed of all protein sequences in reversed order. Searches were performed using a 50 ppm precursor ion tolerance. Product ion tolerance was set to 0.003 Th. Carbamidomethylation of cysteine residues (57.02146 Da) were set as static modifications, while oxidation of methionine residues (+15.99492 Da) was set as a variable modification.

Peptide spectral matches (PSMs) were altered to a 1% FDR (Elias and Gygi, 2010, Elias and Gygi, 2007). PSM filtering was performed using a linear discriminant analysis, as described previously (Huttlin et al., 2010), while considering the following parameters: XCorr, ΔCn, missed cleavages, peptide length, charge state, and precursor mass accuracy. Peptide-spectral matches were identified, quantified, and collapsed to a 1% FDR and then further collapsed to a final protein-level FDR of 1%. Furthermore, protein assembly was guided by principles of parsimony to produce the smallest set of proteins necessary to account for all observed peptides.

TMT labeling sample preparation and mass spectrometry analysis

The TMT labeling and subsequent mass spectrometry analysis was based on the SL-TMT sample process strategy (Navarrete-Perea et al., 2018). Briefly, TMT reagents (0.8 mg) were dissolved in anhydrous acetonitrile (40 μL) of which 10 L was added to the peptides (100 μg) along with 30 L of acetonitrile to achieve a final acetonitrile concentration of approximately 30% (v/v). Following incubation at room temperature for 1 h, the reaction was quenched with hydroxylamine to a final concentration of 0.3% (v/v). The TMT-labeled samples were pooled at a 1:1 ratio across all channels. The sample was vacuum centrifuged to near dryness and subjected to C18 solid-phase extraction (SPE) (Sep-Pak, Waters).

Basic pH reversed-phase (BPRP) fractionation allowed for deep proteome analysis.

A total of 100 μg of peptide from each of channels was combined, desalted, and fractionated with basic pH reversed-phase (BPRP) chromatography. Following desalting, peptides were resuspended in buffer A (10 mM ammonium bicarbonate, 5% acetonitrile, pH 8) and loaded onto an Agilent 300Extend C18 column (5 μm particles, 4.6 mm ID and 220 mm in length). The peptide mixture was fractionated with a 60 min linear gradient from 0% to 42% buffer B (10 mM ammonium bicarbonate, 90% ACN, pH 8). A total of 96 fractions were collected and concatenated so that every 24th fraction was pooled (i.e., samples in wells A1, C1, E1, and G1 were combined) and only alternating pooled fractions (a total of 12) were analyzed (Paulo et al., 2016a).

Liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry.

The samples were reconstituted in 5% acetonitrile and 5% formic acid for LC-MS/MS processing. Peptides were separated on a 35 cm long, 100 μm inner diameter microcapillary column packed with Accucore (2.6 m, 150Å) resin (ThermoFisher Scientific). For each analysis, we loaded 2 μg of the sample onto the C18 capillary column using a Proxeon NanoLC-1200 UHPLC. Peptides were separated in-line with the mass spectrometer using gradients of 6 to 26% acetonitrile in 0.125% formic acid at a flow rate of ~500 nL/min. Data was collected using the SPS-MS3 method on an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos mass spectrometer. Peptides were separated using a 150 min gradient of 3 to 25% acetonitrile in 0.125% formic acid with a flow rate of 450 nL/min. Each analysis used an MS3-based TMT method (Ting et al., 2011, McAlister et al., 2014), which has been shown to reduce ion interference compared to MS2 quantification (Paulo et al., 2016b). Prior to starting our analysis, we perform two injections of trifluoroethanol (TFE) to elute any peptides that may be bound to the analytical column from prior injections to limit carry over. The scan sequence began with an MS1 spectrum (Orbitrap analysis, resolution 120,000, 350–1400 Th, automatic gain control (AGC) target 5E5, maximum injection time 100 ms). The top ten precursors were then selected for MS2/MS3 analysis. MS2 analysis consisted of: collision-induced dissociation (CID), quadrupole ion trap analysis, automatic gain control (AGC) 1.8E4, NCE (normalized collision energy) 35, q-value 0.25, maximum injection time 120 ms), and isolation window at 0.7. Following acquisition of each MS2 spectrum, we collected an MS3 spectrum in which multiple MS2 fragment ions are captured in the MS3 precursor population using isolation waveforms with multiple frequency notches. MS3 precursors were fragmented by HCD and analyzed using the Orbitrap (NCE 65, AGC 1.5E5, maximum injection time 150 ms, resolution was 50,000 at 400 Th). For MS3 analysis, we used charge state-dependent isolation windows: For charge state z=2, the isolation window was set at 1.3 Th, for z=3 at 1 Th, for z=4 at 0.8 Th, and for z=5 at 0.7 Th.

Data analysis.

Mass spectra were processed using a SEQUEST-based software pipeline (Huttlin et al., 2010). Database searching included all entries from the Uniprot Schizosaccharomyces pombe (downloaded: November 11, 2017). This database was concatenated with one composed of all protein sequences in the reversed order. Searches were performed using a 50 ppm precursor ion tolerance. The product ion tolerance was set to 0.9 Da. These wide mass tolerance windows were chosen to maximize sensitivity in conjunction with SEQUEST searches and linear discriminant analysis (Beausoleil et al., 2006, McAlister et al., 2012). TMT tags on lysine residues and peptide N termini (+229.163 Da) and carbamidomethylation of cysteine residues (+57.021 Da) were set as static modifications, while oxidation of methionine residues (+15.995 Da) was set as a variable modification.

Peptide-spectrum matches (PSMs) were adjusted to a 1% false discovery rate (FDR) (Elias and Gygi, 2007, Elias and Gygi, 2010). PSM filtering was performed using a linear discriminant analysis, as described previously (Huttlin et al., 2010), while considering the following parameters: XCorr, ΔCn, missed cleavages, peptide length, charge state, and precursor mass accuracy. For TMT-based reporter ion quantitation, we extracted the signal-to-noise (S:N) ratio for each TMT channel and found the closest matching centroid to the expected mass of the TMT reporter ion. PSMs were identified, quantified, and collapsed to a 1% peptide false discovery rate (FDR) and then collapsed further to a final protein-level FDR of 1%. Moreover, protein assembly was guided by principles of parsimony to produce the smallest set of proteins necessary to account for all observed peptides.

Peptide intensities were quantified by summing reporter ion counts across all matching PSMs to give greater weight to more intense ions (McAlister et al., 2012, McAlister et al., 2014). PSMs with poor quality, MS3 spectra with TMT reporter summed signal-to-noise measurements that were less than 60, or with no MS3 spectra were excluded from quantification. Isolation specificity of ≥ 0.7 (i.e., peptide purity >70%) was required (McAlister et al., 2012).

Mass spectrometry analysis of histone post-translational modification

Three-liter cultures of Flag-Swi6 and Bdf2-Flag strains were grown in YES to log phase, 2.5 × 107 cells/ml, and washed twice with 1× TBS. Protein purification was performed as described in the previous section for Flag-Swi6/Bdf2-Flag purifications. Around 5% of the eluted protein was analyzed by silver staining. The remaining eluted proteins were dried overnight using vacuum centrifugation and resolved in a 4–12% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel. The gel was coomassie stained and placed on a clean glass plate wiped with methanol. Bands lower than 20 kDa were excised using a clean scalpel and processed for in-gel chemical derivatization and trypsin digestion. Briefly, gel bands were sliced into 1mm2 pieces in 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate. After rinsing by shaking for a few minutes, the ammonium bicarbonate buffer was removed and the gel pieces were further dehydrated using 100% acetonitrile. Chemical derivatization for unmodified lysines and trypsin digestion at arginine were performed for bottom up mass spectrometry as described previously (Sidoli et al., 2016), by alternately swelling in ammonium bicarbonate buffer and dehydrating using 100% acetonitrile. The tryptic peptides were squeezed out of gel pieces and capped at N-termini by further derivatization of the supernatant. Using C18 Stage-tips, these samples were desalted prior LC-MS analysis. In an nLC coupled to mass spectrometer, the peptides were separated using a 75 μm ID × 17 cm Reprosil-Pur C18-AQ (3 μm; Dr. Maisch GmbH, Germany) nano-column fitted on an EASY-nLC nanoHPLC (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, Ca, USA). The HPLC gradient comprising 2% to 28% solvent B (A = 0.1% formic acid; B = 95% MeCN, 0.1% formic acid) over 45 minutes, from 28% to 80% solvent B in 5 minutes, 80% B for 10 minutes at a flow-rate of 300 nL/min was used. Data-independent acquisition (DIA) was used to acquire data using LTQ-Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific)(Sidoli et al., 2015). Briefly, full scan MS (m/z 300–1100) was acquired in the Orbitrap with a resolution of 120,000 (at 200 m/z) and an AGC target of 5×105. MS/MS was performed in centroid mode in the ion trap with sequential isolation windows of 50 m/z with an AGC target of 3×104, a CID collision energy of 36 and a maximum injection time of 50 msec,. Data were analyzed using the EpiProfile with S. pombe database (Yuan et al., 2015) wherein the peptide relative ratio was calculated using the total area under the extracted ion chromatograms of all peptides with the same amino acid sequence (including all of its modified forms) as 100%.

Microscopy

Live fission yeast cells were mounted on No. 1.5 glass coverslips in YEA medium (Electron Microscopy Sciences). Images were collected using a Yokogawa CSU-X1 spinning disk confocal on a Nikon Ti-E inverted microscope equipped with a Spectral Applied Research LMM-7 laser launch with AOTF control of intensity and wavelength, and a Hamamatsu ORCA-AG cooled CCD camera controlled with MetaMorph 7 software. Cnp1-GFP, Gar1-GFP and GFP-Swi6 were imaged with a 491 nm solid state laser and a 535/50 emission filter, and Lem2-mKO2 and Cut11- mKO2 were imaged with a 561 nm solid state laser and 620/60 emission filter, both using a QUAD 405/491/561/642 dichroic. All filters were made by Chroma Technologies. Images were acquired using a Nikon Plan Apo 100 × 1.45 NA oil immersion objective. For each acquired image, 13–17 focal plane z-series were collected with a step size of 0.25 μm using the internal Nikon Ti focus motor. Images in the figures are displayed as maximum intensity z-projections, brightness and contrast were adjusted identically for compared image sets using FIJI software. 3D reconstruction images in Figure 4D were generated with volume tools of Imaris software (version 8.4.1, Bitplane Inc).

Gar1-GFP, Cnp1-GFP and GFP-Swi6 image analysis

To investigate the effects of Lem2, Nur1 and Clr4 mutations on Gar1-GFP size, we analyzed cells from two independently isolated single deletions of each of lem2+, nur1+ and clr4+, and two independently isolated lem2Δ nur1Δ double mutant strains (40–70 cells each strain) and compared them with parental wild type cells. Imaris software (version 8.4.1, Bitplane Inc.) was used for this analysis. In the Imaris Surpass mode, a new 3D cell was created using the “Detect cell and nucleus” mode of the Cell module. The nuclear membrane reconstruction was created based on the Cut11-mKO2 signal and the Gar1 domain was reconstructed based on the Gar1-GFP signal. After the completion of the analysis we extracted the data for nuclear (Cut11-mKO2) and nucleolar (Gar1-GFP) volume (μm3) for each cell. The ratio of nucleolar to nuclear volume was calculated by dividing the volume of Gar1-GFP domain with the total volume of the nucleus for each cell individually. The means for these parameters were calculated for each cell separately and then the averages from all cells were plotted as average numbers for wild-type and mutant cells. Unpaired t-tests were used for the statistical analysis of the data. To quantify nucleolar fragmentation observed in lem2Δ and nur1Δ mutant cells, we created maximum intensity projections of the Gar1-GFP images and used the “Cell Counter” plugin in the FIJI software to count the number of cells with Gar1-GFP foci outside the nucleus as defined by the Cut11-mKO2 signal.

To analyze the effect of deleting npp106+, nup40+, alm1+ on the number of Swi6 foci, deletion of npp106+ on Taz1 foci, and deletions of npp106+, lem2+, and nur1+ on Cnp1-GFP clustering, we created maximum intensity projections of GFP-Swi6 or Cnp1-GFP images and used the “Cell Counter” plugin in the FIJI software to count the number of cells in which GFP-Swi6 foci or the Cnp1-GFP focus were de-clustered. For this analysis, we compared two independent deletions of each of the above genes with wild-type cells (200–300 cells for each genotype for analysis of GFP-Swi6 foci). The percentages of cells with de-clustered GFP-Swi6 or Cnp1-GFP were plotted in the figures for each strain.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and quantitative real time PCR (qPCR)

ChIP was performed essentially as described (Jih et al., 2017). Briefly, 50-ml cultures of cells were grown overnight (or 24 h when 5 μg/ml tetracycline was added) in YEA to an optical density (OD) of 2–3 and fixed as follows. For H3K9me2, H3K9me3, and H3K14ac ChIP, cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. For Swi6 and other Flag–, GFP–, TAP–, and Myc–protein ChIP, we used a modified dual-crosslinking protocol in which cells were first incubated at 18 °C for 2 hrs, resuspended in 5 ml of room temperature 1x PBS, and fixed with 1.5 mM ethylene glycol bis-succinimidyl succinate (EGS, Thermo Scientific 21565) for 30 min, followed by addition of formaldehyde to 1% final concentration for another 30 min (Zeng et al., 2006). Cells were quenched with 130 mM glycine for 5 min, harvested and washed twice with 1x TBS (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl). Cells were then resuspended in 500 μl lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, and protease inhibitors) in 2 ml screw-cap tubes and lysed by bead beating with 1 ml acid-washed 0.5 mm glass beads with 6 cycles of 30 sec at 5000 rpm on a MagNA Lyser Instrument (Roche). Extracts were sonicated for 3×20 sec at 50% amplitude using a sonicator (Branson Digital Sonifier). For each ChIP, approximately 2 μg of antibody was pre-incubated with 30 μl of Invitrogen Dynabeads Protein A, Protein G or IgG (for TAP tagged strains): anti-H3K9me2 (Abcam 1220) with protein A, anti-H3K14ac (Millipore 07–353) with protein-A, anti-Flag (Sigma F1804) with protein G, anti-Swi6 (rabbit polyclonal) with protein A, anti-GFP (Abcam 290) with protein A, and anti-Myc (Covance 9E10, MMS-150P) with protein G. For H3K9me3 ChIP, 1 μg of anti-H3K9me3 antibody (Diagenode, C15500003) was first incubated with 30 μl Dynabeads M-280 Streptavidin beads (Invitrogen) at 4 °C for 1 hr, followed by blocking with 5 μM biotin, according to the manufacturer’s instructions, prior to using for each immunoprecipitation.