Abstract

Black communities in the United States are bearing the brunt of the COVID-19 pandemic and the underlying conditions that exacerbate its negative consequences. Syndemic theory provides a useful framework for understanding how such interacting epidemics develop under conditions of health and social disparity. Multiple historical and present-day factors have created the syndemic conditions within which black Americans experience the lethal force of COVID-19. These factors include racism and its manifestations (e.g., chattel slavery, mortgage redlining, political gerrymandering, lack of Medicaid expansion, employment discrimination, and health care provider bias). Improving racial disparities in COVID-19 will require that we implement policies that address structural racism at the root of these disparities.

Keywords: Black Americans, COVID-19, Syndemic theory, Health disparities, HIV

As COVID-19 cases have exploded in the United States, stark racial disparities in morbidity and mortality have emerged. The burden is most pronounced for black Americans who make up 13% of the U.S. population but 30% of COVID-19 cases in the 14 states for which racial data were available [1]. Rates of exposure and infection with the novel pathogen may also differ by race; however, the lack of widespread testing and limited reporting of racial data make this difficult to ascertain. A variety of explanations have been offered for this emerging health inequity: Black Americans experience a higher prevalence of underlying chronic conditions, such as hypertension (57%) [2], diabetes (18%) [3], and obesity (50%) [4], which predispose individuals to poorer clinical outcomes, including death, in the event of COVID-19 disease [5]. Black Americans are 1.5 times more likely to be underinsured or lack health insurance altogether than whites [6], contributing to delayed access to lifesaving care [7]. On April 17, 2020, U.S. Surgeon General Jerome Adams even suggested black Americans have higher substance use rates and recommended they reduce substance use, alcohol consumption, and smoking to prevent COVID-19 deaths [8]. While these factors may play a role in why black American communities face greater losses in this pandemic, decades of research to understand the disproportionate burden of HIV among black Americans may help unmask the drivers of this inequity and improve efforts to mitigate it.

It is a longstanding paradox that black Americans carry the highest burdens of HIV while also reporting similar rates of HIV risk behaviors as other groups. This holds true for black American men who have sex with men as well as for black American women [9,10]. Syndemic theory has provided a useful framework for understanding this paradox [11]. Anthropologist Merrill Singer first proffered syndemic theory as a way “to elucidate the tendency for multiple co-terminus and interacting epidemics to develop under conditions of health and social disparity” [12]. The high rate of COVID-19 exposure, acquisition, and mortality among black Americans represents “multiple co-terminus and interacting epidemics” occurring within persistent national health and social inequities already impacting black communities. Multiple historical and present-day factors have created the syndemic conditions within which black Americans experience the lethal force of COVID-19.

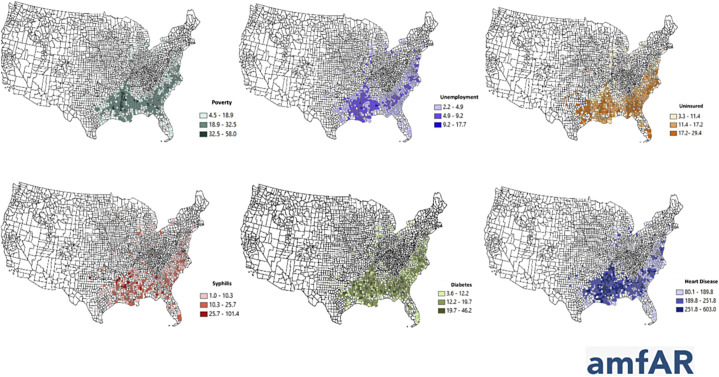

The health impact of social and political decisions outweighs the impact of individual choices, and these decisions have a historical context. Sociological and economic studies have shown correlations between modern-day attitudes and policies in former confederate states and policies that disenfranchise black Americans [13]. Of 677 disproportionally black counties (≥13% black Americans), 91% are concentrated in the southern United States [14]. Strikingly, not only are rates of unemployment and uninsurance high in those counties, but also diabetes, heart disease, and HIV (Fig. 1 ). It is likely that these preexisting conditions play an important role in poor clinical outcomes from COVID-19 in these counties.

Fig. 1.

Overlapping socioeconomic and health conditions (syndemic) in counties with a disproportionate (≥13%) black population. Figure courtesy of amfAR, excerpted from Greg Millett's July AIDS 2020 plenary.

State governments in the South have fiercely resisted the Medicaid expansion component of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), thereby limiting health insurance access for many of the working poor. It is not lost on many black Americans that part of the repudiation of the ACA—a policy that provided insurance to an additional 20 million Americans—is a direct repudiation of Barack Obama (our country's first black president) [15]. Such corrosive politics have health consequences. Uninsured or underinsured Americans often delay seeking timely health care because of costs and are more likely to present when a disease has progressed.

Delays in access to COVID-19 testing is also a function of the intersection of economics and racism. Recent data on testing availability have demonstrated the lack of testing options in low-income neighborhoods, and “drive-by” sites are only accessible to people with a private car. One analysis found six-fold higher rates of COVID-19 testing in high-income neighborhoods in Philadelphia despite higher COVID-19-positive tests in poorer black neighborhoods [16]. Such inequities are magnified by medical provider bias. A long legacy of medical mistreatment, present day racial bias in clinical decision making, and minimization of black American patients' symptoms impact access to health technologies [17]. This dynamic is evident in the limited availability of COVID-19 testing and media reports of hospitals that refused to test and/or turned away black Americans with COVID-19 symptoms [[18], [19], [20]].

Black Americans are overrepresented in essential service industries, including low-wage health care sectors such as home health aides, nursing home staff, and hospital janitorial, food service, laundry, and other sectors [21]. Many of these low-wage jobs do not provide adequate, if any, health insurance, sick leave, childcare, or other benefits which protect higher wage workers from COVID-19 exposures. Moreover, the surrounding environment magnifies risk. Black Americans are more likely to live in crowded settings such as public housing where the ability to practice social distancing is quite limited, if not impossible [22]. The preponderance of black Americans in occupations, environments, and situations that increase exposure to the novel coronavirus is not accidental but grounded in the historical and modern-day structural violence of racism. Racism is a form of structural violence because it produces socially unjust conditions that predispose black communities to disability and death—a reality that is both normalized and reproduced within the practices and policies of enduring public and private institutions [23]. Examples range from historical mortgage redlining that undermined black economic progress to current attempts at racial gerrymandering to disenfranchise black political power [24,25].

The partisan politicization of COVID-19 is also a detriment to black Americans. A Princeton professor who analyzed cell phone data to assess social distancing patterns in the United States found a striking pattern that exemplifies the sociopolitical drivers of syndemic conditions. Counties with the greatest share of votes for Trump in the 2016 election were least likely to practice social distancing, and the greater the share of residents who denied climate change, the worse the county scored on social distancing [26]. Repudiation of science related to both climate change and COVID-19 is encouraged by the Trump administration, and both have disproportionate impacts on black communities [[27], [28], [29]]. Resistance to climate change and Trump support are both high among white people in the southern United States [30,31], and it is no coincidence that the push to suspend stay-at-home orders and to prematurely reopen economies are being led by governors of southern states (e.g., Georgia, Texas, South Carolina). Ironically, Georgia (which has been among the most aggressive in suspending public health practices implemented to curb COVID-19 transmission) is not only the home to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, but also where one of the most devastating COVID-19 outbreaks nationwide has taken place among black residents [32]. Dougherty County, Georgia, has a per-capita COVID-19 death rate of 27 per 100,000 with 81% of deaths among black Americans who make up 69% of the population [33]. Relaxing public health measures will undoubtedly exacerbate existing racial disparities.

As a discipline, epidemiology aims to produce information for action. Improving reporting of race in surveillance and screening programs is an essential step to ensure disparities are accurately tracked. However, we do not need to wait for surveillance programs to act. The pattern is clear. To address these disparities in the short term, we must compensate low-wage service workers who have not had the option to stay at home and have kept our society functioning through this devastating pandemic. We must push for a living wage for all workers; provide universal health care access that is not tethered to employment or income; and demand personal protective equipment, access to testing, paid sick leave, and other basic minimums for essential workers who face life-threatening occupational exposures. Although important, these actions are insufficient to address the inequities rooted in syndemic conditions.

We all are not at equal risk for COVID-19. Like other conditions, this is decidedly a racialized disease. The racial health inequities that we are seeing have not emerged randomly nor passively; rather, they are actively produced through anti-black racism institutionalized within the American political system. The field of epidemiology must now reckon with a heightened awareness that the system of racism is more than a passive backdrop; it is a dynamic functioning epidemic that has converged with the COVID-19 pandemic to accelerate exposure, disease, and mortality among black people in America. While science endeavors to remain nonpartisan, its effectiveness in protecting the health of populations will be minimized if it is silent on the influence of politics on the disproportionate rates of illness and death experienced by black people in this country. Our scientific approach to addressing drivers of these inequities must change in response to our awareness of systemic racism. The timeframe for change is up to us. Better to embrace the fierce urgency of now.

Acknowledgments

All authors have no competing interests to declare.

Supported by the Desmond M. Tutu Professorship in Public Health and Human Rights at Johns Hopkins University.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Cases of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) in the U.S. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html

- 2.Ostchega Y., Fryar C.D., Nwankwo T., Nguyen D.T. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2020. Hypertension prevalence among adults aged 18 and over: United States, 2017–2018. NCHS Data Brief No. 364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mendola N.D., Chen T.-C., Gu Q., Eberhardt M.S., Saydah S. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2018. Prevalence of total, diagnosed, and undiagnosed diabetes among adults: United States, 2013–2016. NCHS Data Brief No. 319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hales C.M., Carroll M.D., Fryar C.D., Ogden C.L. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2020. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among adults: United States, 2017–2018. HCHS Data Brief No. 360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marron M.M., Ives D.G., Boudreau R.M., Harris T.B., Newman A.B. Racial differences in cause-specific mortality between community-dwelling older black and white adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(10):1980–1986. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Artiga S., Orgera K., Damico A. Kaiser Family Foundation, Issue Brief. 2019. Changes in health coverage by race and ethnicity since implementation of the ACA, 2013–2017.https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/changes-in-health-coverage-by-race-and-ethnicity-since-the-aca-2010-2018/ [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stimpson J.P., Wilson F.A. Medicaid expansion improved health insurance coverage for immigrants, but disparities persist. Health Aff (Millwood) 2018;37(10):1656–1662. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kayla B., Nikki S. Daily Mail. 2020. Surgeon General is under fire for telling Black Americans not to smoke, drink or take drugs and ‘highly offensive’ use of ‘big momma’ as coronavirus pandemic hits black community hardest.https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8210359/Surgeon-general-fire-offensive-instruction-black-Americans-not-smoke-drink.html [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adimora A.A., Cole S.R., Eron J.J. US black women and human immunodeficiency virus prevention: time for new approaches to clinical trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(2):324–327. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Millett G.A., Jeffries WLt, Peterson J.L., Malebranche D.J., Lane T., Flores S.A. Common roots: a contextual review of HIV epidemics in black men who have sex with men across the African diaspora. Lancet. 2012;380(9839):411–423. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60722-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dyer T.P., Shoptaw S., Guadamuz T.E., Plankey M., Kao U., Ostrow D. Application of syndemic theory to black men who have sex with men in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. J Urban Health. 2012;89(4):697–708. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9674-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singer M.C., Erickson P.I., Badiane L., Diaz R., Ortiz D., Abraham T. Syndemics, sex and the city: understanding sexually transmitted diseases in social and cultural context. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(8):2010–2021. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams R.A. Eliminating Healthc Disparities America. Humana Press Inc; Totowa, NJ: 2007. Historical perspectives of healthcare disparities; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schaeffer K. Pew Research Center; Washington, DC: 2019. In a rising number of U.S. counties, Hispanic and black Americans are the majority.https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/11/20/in-a-rising-number-of-u-s-counties-hispanic-and-black-americans-are-the-majority/ [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeffries M.P. Obamacare repeal is based on racial resentment. 2017. https://www.bostonglobe.com/opinion/2017/05/05/obamacare-repeal-based-racial-resentment/iVNtB9fpr3JNm7IKfYyorK/story.html

- 16.Lubrano A. High-income Philadelphians getting tested for coronavirus at far higher rates than low-income residents. The Philadelphia Inquirer. 2020. https://www.inquirer.com/news/philadelphia/coronavirus-testing-inequality-poverty-philadelphia-health-insurance-20200406.html

- 17.van Ryn M., Burgess D.J., Dovidio J.F., Phelan S.M., Saha S., Malat J. The impact of racism on clinician cognition, behavior, and clinical decision-making. Du Bois Rev. 2011;8(1):199–218. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X11000191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitropoulos A., Moseley M. Beloved Brooklyn teacher, 30, dies of coronavirus after she was twice denied a COVID-19 test. ABC News. 2020. https://abcnews.go.com/Health/beloved-brooklyn-teacher-30-dies-coronavirus-denied-covid/story?id=70376445

- 19.Shamus K.J. Family ravaged by coronavirus begged for tests, hospital care but was repeatedly denied. USA Today. 2020. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2020/04/20/coronavirus-racial-disparity-denied-tests-hospitalization/5163056002/

- 20.Lothian-Mclean M. Black woman in US dies after being turned away from hospital she worked at for 31 years. Independent. 2020. https://www.indy100.com/article/coronavirus-black-health-care-worker-dies-test-detroit-deborah-gatewood-9485341

- 21.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics . BLS Reports. 2019. Characteristics of minimum wage workers, 2018.https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/minimum-wage/2018/pdf/home.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 22.U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development . 2020. Resident Characteristic Report [database on the Internet]https://pic.hud.gov/pic/RCRPublic/rcrmain.asp [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farmer P.E., Nizeye B., Stulac S., Keshavjee S. Structural violence and clinical medicine. PLoS Med. 2006;3(10):e449. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Massey D.S., Denton N.A. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1993. American apartheid: segregation and the making of the underclass. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Durst N.J. Racial gerrymandering of municipal borders: direct democracy, participatory democracy, and voting rights in the United States. Ann Am Assoc Geogr. 2018;108(4):938–954. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharkey P. The US has a collective action problem that's larger than the coronavirus crisis: data show one of the strongest predictors of social distancing behavior is attitudes toward climate change. Vox. 2020. https://www.vox.com/2020/4/10/21216216/coronavirus-social-distancing-texas-unacast-climate-change

- 27.Macdonald M. 2019. We Must Treat Climate Change as a Racial Justice Issue.https://changewire.org/we-must-treat-climate-change-as-a-racial-justice-issue/ [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shear M.D., Mervosh S. Trump encourages protest against governors who have imposed virus restrictions. New York Times. 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/17/us/politics/trump-coronavirus-governors.html

- 29.Trump on climate change report: 'I don't believe it'. BBC News. 2018. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-46351940

- 30.Ballew M., Maibach E., Kotcher J., Bergquist P., Rosenthal S., Marlon J. Which racial/ethnic groups care most about climate change? Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. 2020. https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/publications/race-and-climate-change/

- 31.Reality check: Who voted for Donald Trump? BBC News. 2016. https://www.bbc.com/news/election-us-2016-37922587

- 32.Fowler M. 'It Hit Like a Bomb.' A georgia coroner on how the coronavirus is ravaging his community. Time. 2020. https://time.com/collection/coronavirus-heroes/5816891/coroner-georgia-coronavirus/

- 33.Dougherty County, GA Census Reporter. https://censusreporter.org/profiles/05000US13095-dougherty-county-ga/