Abstract

A current approach in bone tissue engineering is the implantation of polymeric scaffolds that promote osteoblast attachment and growth as well as biomineralization. One promising polymer is oligo[poly(ethylene glycol) fumarate] (OPF), a polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based material that is biocompatible, injectable, and biodegradable, but in its native form doesn’t support robust bone cell attachment or growth. To address this issue, this study evaluated the osteoconductivity of bis[2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl] phosphate (BP) functionalized OPF hydrogels (OPF-BP) using MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblast cells, both before and after enzymatic mineralization with a calcium solution. The inclusion of negatively charged functional groups allowed for the tailored uptake and release of calcium, while also altering the mechanical properties and surface topography of the hydrogel surface. In cell culture, OPF-BP hydrogels with 20% and 30% (w/w) BP optimized osteoblast attachment, proliferation, and differentiation after a 21-day in vitro period. In addition, the OPF-BP30 treatment, when mineralized with calcium, exhibited a 128% increase in osteocalcin expression when compared with the non-mineralized treatment. These findings suggest that phosphate functionalization and enzymatic calcium mineralization can act synergistically to enhance the osteoconductivity of OPF hydrogels, making this processed material an attractive candidate for bone tissue engineering applications.

Keywords: Bone tissue engineering, osteoconduction, bis[2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl] phosphate (BP), osteoblast, phosphate functional groups

1. Introduction

Bone is the second most commonly transplanted tissue worldwide, with a diverse array of clinical uses, including the replacement of tissue lost to degradation, surgical removal, or trauma1. While autologous bone grafts remain the ‘gold standard’ for bone tissue replacement, the limited supply of acceptable grafting sites, prevalence of donor site morbidity, and high risk of failure continues to motivate the development of effective alternatives2–4. To address these problems, bone tissue engineering has led to the development of metallic, ceramic, natural, and synthetic polymers that support bone regeneration5,6.

Bone regeneration remains challenging in large part due to the non-static nature of itself. Bone is continually being remodeled by either osteoblasts, cells that produce bone matrix, or osteoclasts, cells that selectively degrade and remodel intact bone7. While materials that promote bone formation, mineralization, and integration with native tissues have been sought after for decades, the slow degradation rate of many developed materials interfere with cellular bone remodeling5,8. Additionally, the surgical implantation of traditional materials that perform well in vitro, such as metals and/or ceramics, remains an invasive intervention9, motivating the development of injectable materials that can polymerize on-demand10 and allow for the incorporation of growth factors, drugs, and even cells to enhance their regenerative capacity11–13.

A synthetic polymer that addresses many of these challenges is oligo[poly(ethylene glycol) fumarate] (OPF), a polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based material that is biocompatible, injectable, and biodegradable14. Through functionalization and co-polymerization, the physical and chemical properties of OPF are highly tunable15,16, allowing the material to overcome the poor cell attachment and biomineralization reported with other PEG-based biomaterials17,18, while maintaining the reproducibility and ease of fabrication that remains a hallmark of synthetic polymers19. Specific to bone tissue engineering, the incorporation of bioactive minerals into composite OPF hydrogels20–22 provide nucleation sites in situ, promoting hydrogel mineralization and integration with extant tissues as the polymer is resorbed23,24.

The incorporation of inorganic phases into hydrogels stands to expand the success that has been seen with soft material regeneration15,25 to hard tissues26–28, particularly in the case of bone where a negatively charged material can support calcification and mineral formation. Previous work from our laboratory has shown that phosphate functionalization through the crosslinking of bis[2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl] phosphate (BP) facilitates mineral nucleation and improves osteogenesis in OPF hydrogels over a seven day period18, while also promoting bone formation in a rat orthotopic defect model over nine weeks29. Phosphates help to regulate calcification and bone resorption30–32 through the inhibition of osteoclast recruitment and differentiation33, the induction of mature osteoclast apoptosis34, and subsequent promotion of osteoblast activity. What remains unclear from this current body of work is what degree of phosphate functionalization and calcification is needed to maximize bone regeneration.

In this study, we aim to expand upon our previous work evaluating the osteoconductive and osteoinductive capacity of phosphate functionalized OPF hydrogels (OPF-BP) by investigating the effect of pre-implantation calcium mineralization on osteoblast activity using MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblast cells. We hypothesize that the degree of phosphate functionalization (0–50%, BP w/w OPF) within the polymer network will influence the calcium uptake and release kinetics of the degradation products, which in turn will improve the regulation of osteoblast attachment, proliferation, and differentiation. The effect of BP incorporation and calcium mineralization on the rheological properties, mineral release kinetics, and surface topography of hydrogels were also investigated, with the goal of identifying an optimized formulation for bone regeneration. Biodegradable and injectable synthetic hydrogels that can be functionalized and mineralized before implantation remain an exciting direction for bone tissue engineering that stands to compliment, rather than interfere with, the biological processes required for bone regeneration.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Polymer synthesis

Oligo[poly(ethylene glycol) fumarate] (OPF) was synthesized using polyethylene glycol (PEG; Sigma-Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI) with a number-average molecular weight (Mn) of 10,000 as previously described35. Briefly, 50 g of dried PEG dissolved in methylene chloride and purged in an ice bath under flowing nitrogen for 10 min, followed by the dropwise addition of 0.9 M triethylamine (TEA; Sigma-Aldrich) and 1.8 M distilled fumaryl chloride (Acros, Pittsburgh, PA) per mol of PEG. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 48 h, followed by the removal of methylene chloride and crystallization of OPF in ethyl acetate. Dried OPF was stored at −20°C for up to 1 month before use.

2.2. Hydrogel fabrication and characterization

The fabrication of OPF hydrogels containing various concentrations of bis[2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl] phosphate (BP; Sigma-Aldrich) was accomplished with the use of the photoinitiator 1-[4-(2-Hydroxyethoxy)-phenyl]-2-hydroxy-2-methyl-1-propane-1-one (Irgacure 2959; Ciba Specialty Chemicals, Basel, Switzerland) and the cross-linking agent 1-vinyl-2-pyrrolidinone (NVP; Sigma-Aldrich) as described elsewhere18. Briefly, for each treatment, 1 g of OPF was added to 2 mL of distilled and deionized H2O (ddH2O) and 0.3 g of NVP and heated to 40°C for 20 min. BP was then added (0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, or 0.5 g) followed by the addition of 1.5 mg of Irgacure 2959 (See Table 1 for formulation details), resulting in six treatments with different proportions (w/w) of BP to OPF (OPF, OPF-BP10, OPF-BP20, OPF-BP30, OPF-BP40, and OPF-BP50). Formulations were then pipetted between two glass plates with a 1 mm spacer, bound with binder clips, and cured in a UV oven (365 nm, 1.2 mW cm2 intensity) for 4 h.

Table 1.

Physical characteristics of hydrogel formulations with varying BP concentrations. Values represent the mean ± standard error for each treatment (n=5). Letters denote the result of post-hoc Tukey HSD comparisons between groups.

| Hydrogel formulation | % BP w/w OPF | BP (μmol) | Swelling ratio | Sol fraction (%) | Protein adsorbed (μg cm−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPF | 0 | 0 | 10.5 ± 1.8a | 15.9 ± 5.3a | 10.1 ± 1.0a |

| OPF-BP10 | 10 | 310 | 23.9 ± 1.9b | 14.4 ± 1.2a | 6.9 ± 1.4a |

| OPF-BP20 | 20 | 620 | 17.0 ± 2.0a | 20.1 ± 3.0ab | 16.5 ± 2.3b |

| OPF-BP30 | 30 | 931 | 14.2 ± 2.2a | 13.2 ± 2.2a | 18.5 ± 1.8b |

| OPF-BP40 | 40 | 1241 | 12.1 ± 3.7a | 18.7 ± 4.6b | 22.3 ± 3.7b |

| OPF-BP50 | 50 | 1551 | 12.9 ± 1.8a | 21.8 ± 5.8b | 23.0 ± 3.0b |

Following fabrication, OPF-BP hydrogel films were cut into discs (D = 10 mm, H = 1 mm) using a cork borer. The swelling ratio and sol fraction of hydrogels were determined by comparing the weight of discs after crosslinking and drying (Wi), swollen in ddH2O for 24hrs (Ws), and then lyophilized (Wd), as determined by the following equations36:

As defined, the swelling ratio represents the fractional increase in the weight of each hydrogel due to water adsorption, while the sol fraction is the fraction of the polymer that is not part of the cross-linked network.

2.3. Hydrogel calcium mineralization

A subset of OPF-BP hydrogels within each formulation were enzymatically mineralized with calcium following the method outlined by Nijhuis et al.37. Briefly, OPF-BP hydrogel discs were separated into 48 well plates and incubated in 1 mL of a mineralizing solution on an orbital shaker for either 4 h, 1 day, or 3 d at 37°C, with a rotating speed of 120 rpm. The mineralizing solution used consisted of 100 mM urea (Sigma-Aldrich), 5 mM Na2HPO4, 12.5 mM CaCl2, 733 mM NaCl, and 0.04 U mL−1 type III urease from Canavalia ensiformis (Millipore-Sigma, Burlington, MA), adjusted to a pH of 6.0. After mineralization, discs were washed in 2 mL ddH2O for 24 h while shaking to remove any excess solution, with water changes performed every 8 h.

2.4. Rheological properties

The linear viscoelastic properties of mineralized and non-mineralized OPF-BP hydrogels were determined using a torsional dynamic mechanical analyzer, equipped with a 10 mm parallel plate (Discovery Hybrid Rheometer HR-1; TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA). During each test, ddH2O swollen samples were compressed with a constant force of 1.5 ± 0.1 N, and a strain sweep at 1 Hz was performed to identify the viscoelastic region of each sample. A frequency sweep from 1 to 100 rad s−1 was then performed to measure the storage (G’) and loss (G”) modulus for each material, calculating viscosity as the ratio of the two (tan δ; G”/G’). Results are presented as the average of 3–4 hydrogels for each group.

2.5. Surface characterization

To investigate the effect of BP functionalization and/or mineralization on the surface morphology of hydrogels, the surface of both mineralized and non-mineralized hydrogels were imaged with scanning electron microscopy (SEM) accompanied by energy dispersive x-ray analysis (EDS). Prior to imaging, hydrogels were washed in ddH2O for 24 h, lyophilized for 48 h, and mounted to microscope stubs with carbon tape. The surface of each hydrogel was imaged at 5 kV, with a magnification of 1000x, using a Hitachi S-4700 scanning electron microscope, while elemental analysis was performed on 50 μm square sections for 100 s using a Themo Noran System SIX EDS microanalysis system (Middleton, WI). Elemental peak ratios were obtained by comparing the peak height (count) of the calcium and phosphorus peaks, normalized to the height of the carbon peak for each sample.

2.6. Mineralization release kinetics

The amount of calcium and phosphate ions released into solution from mineralized OPF-BP hydrogels was determined over the course of 28 d at 37°C, while shaking at 120 rpm. Directly after mineralization, hydrogels were placed in 48-well plates filled with 1 mL of ddH2O. Each day for 28d, the solution within each well was removed and replaced with fresh ddH2O. The amount of calcium released at each timepoint (1–7, 14, 21, and 28 d) was determined using the APExBIO calcium colorimetric assay kit (Boston, MA, USA; #K2067), while the amount of phosphate released was measured using the Abcam phosphate colorimetric assay kit (Cambridge, UK; Cat #: ab65622). Results are presented as the average of 3–4 hydrogels for each group.

2.7. Osteoblast cell culture and monitoring

To investigate the osteoconductive capacity of each hydrogel formulation, MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblast cells38 were cultured on both mineralized and non-mineralized OPF-BP hydrogels (D=10 mm, H=1 mm) for up to 3 weeks at a time. To prepare for cell seeding, hydrogels were sterilized in 70% ethyl alcohol for 8 h, washed in sterile PBS for 8 h, and subsequently incubated in MEM α cell culture medium overnight. Initial cell seeding was accomplished by adding a 30 μL droplet of suspended cells to the surface of each hydrogel, containing ca. 30,000 cells. Cells were then allowed to settle and attach to the surface of each hydrogel for up to 4 h, followed by the addition of 970 μL of MEM α cell culture medium without ascorbic acid (Gibco, Dublin, Ireland), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco) and 0.5% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco). To ensure the constant availability of oxygen and nutrients to cells, culture media was changed every 2–3 d. The average of 3–4 hydrogels is reported for each metric measured.

Cell proliferation and differentiation were measured by sampling a subset of the hydrogels within each treatment 1, 3, 7, 14, or 21 d after initial cell seeding. Both a metabolic assay (CellTiter 96® Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay; Promega, Madison, WI, USA; Cat #: G3582) and nucleic acid fluorophore assay (Quant-iT™ PicoGreen™ dsDNA assay kit; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA; Cat #: P7589) were used to determine cell proliferation at each timepoint. The coverage of cells on the surface of each hydrogel was investigated using the Live/Dead Kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon, USA), followed by imaging with an LSM 780 confocal microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany); live cells appeared green in this assay while dead cells were stained red. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity was measured using the QuantiChrom™ assay kit (BioAssay Systems, Hayward, CA, USA; Cat #: DALP-250), with results then normalized to the total protein content of each well, as measured with the Bio-Rad BSA protein assay kit (Hercules, CA, USA; Cat #: 5000002). Osteocalcin expression was quantified using the Alfa Aesar™ Mouse Osteocalcin Enzyme Immunoassay kit (Haverhill, MA, USA; Cat #: J64239), also normalized to the total protein content of each well. ALP activity and osteocalcin expression are reported as the fold change in the normalized measure for each value, using the non-mineralized OPF treatment value on day 1 as a control for the MTS and ALP assays, and day 7 for the OCN assay. All results are reported as an average of 3–4 hydrogels.

The cytotoxicity of unreacted BP was evaluated by culturing MC3T3-E1 cells on 12-well tissue culture polystyrene (TCP) plates in media containing a molar concentration of bis[2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl] phosphate ranging from 0–500 mM. Alternatively, the cytotoxicity of crosslinked BP was evaluated by fitting these 12-well plates with transwell chambers (mesh size = 3 μm), each containing a OPF-BP hydrogel disc (D = 8 mm, H = 1 mm) with either 0%, 10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, or 50% w/w ratio of bis[2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl] phosphate to OPF. Cells were either exposed to unreacted BP or the leaching solution from crosslinked OPF-BP hydrogels for 4 days. Cell viability was then determined by quantifying total DNA (ng/scaffold) for 3 hydrogels per group using the PicoGreen assay, normalizing to the TCP control.

2.8. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in R (Version 3.4.1; http://www.r-project.org/) with the RStudio IDE (Version 1.0.153; http://www.rstudio.com/). For each previously described experiment, an ANOVA model was constructed using either G’, G”, tan δ, metabolic activity (OD), total dsDNA (ng/scaffold), normalized ALP activity, or normalized osteocalcin expression as the response variable. For cell culture experiments, each model incorporated the length of time that cells were cultured on hydrogels (fixed effect with five levels), the BP concentration of the hydrogel (fixed effect with six levels), and whether or not the hydrogel was mineralized with calcium (fixed effect with two levels). Before inclusion in a model, the assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity for each variable were confirmed using the Shapiro test in combination with the visual assessment of Q-Q and residual-fitted plots. When normality was violated, response variables were transformed using the Johnson transformation39. For significant effects (α =0.05), the agricolae package was used to perform pairwise comparisons of groups using Tukey HSD post hoc analysis40.

3. Results

3.1. Physical characterization of OPF-BP hydrogels

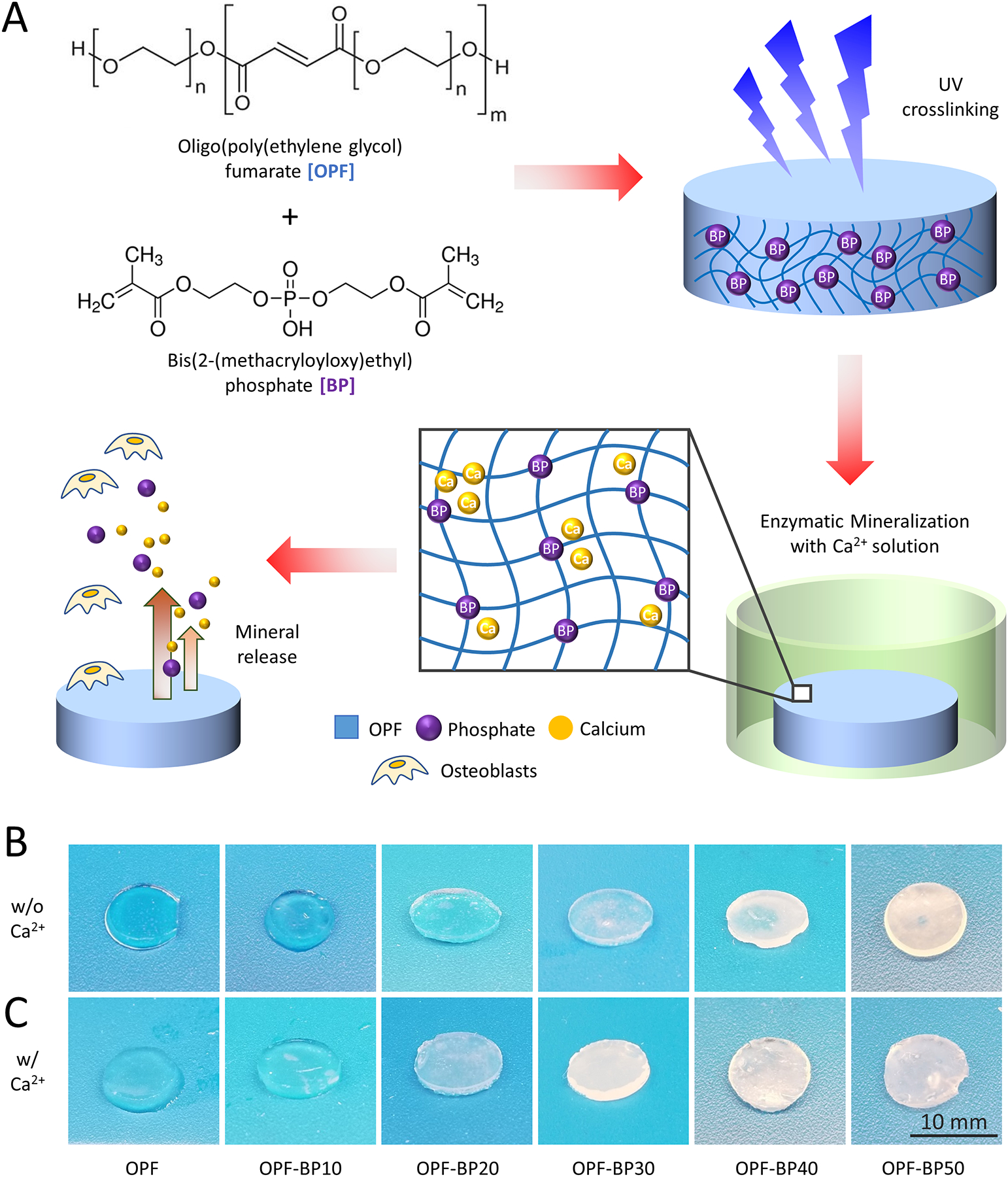

Bis[2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl)] phosphate (BP) was successfully incorporated into OPF hydrogels, altering their coloration, surface morphology, and physical properties (Table 1, Figure 1A). As the concentration of BP increased, hydrogels became opaque (Figure 1B) and displayed a more complex surface topography when viewed under SEM (Figure 2A). The presence of a phosphorus peak in EDS imaging of the surface is consistent with the crosslinking of BP within the OPF polymer network (Figure 2C), with the P:C ratio of hydrogels linearly scaling with BP concentration (r2 = 0.96, p<0.001; Figure 2B,C). BP concentration also affected the swelling ratio (F5,67 = 9.3, p=0.003), sol fraction (F5,67 = 1.34, p=0.02), and amount of protein adsorbed to the surface of hydrogels (F5,18 = 12.8, p<0.001; Table 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of OPF-BP composite hydrogel synthesis, mineralization, and proposed cellular interactions. (A) BP was incorporated into OPF hydrogels (0–50%, BP w/w OPF), solidified using UV, and enzymatically mineralized through submersion in a calcium solution; phosphate and calcium ions are released from the material overtime, attracting osteoblast attachment, proliferation, and differentiation. Both non-mineralized (B) and mineralized (C) hydrogels became opaque as BP concentration increased and/or calcium ions were absorbed.

Figure 2.

(A) Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) imaging of the surface of OPF-BP hydrogels, displaying differences in the surface morphology of both non-mineralized and mineralized samples, at varying degrees of BP functionalization (0–50%, BP w/w OPF). (B) A representative spectrum obtained using energy-dispersive X-ray analysis, through which the elemental peak ratios comparing calcium, carbon, and phosphorus were obtained from mineralized samples (C). The amount of calcium absorbed by each hydrogel (C), as well as the amount of phosphate (E) and calcium (F) released from mineralized hydrogels, is also presented as a function of time and BP concentration.

BP incorporation resulted in changes in the material properties of hydrogels as well, with the storage modulus (F5,378 = 93, p<0.001), loss modulus (F5,378 = 120, p<0.001), and viscosity (F5,378 = 79, p<0.001) shifting with the incorporation of phosphate, leading to the separation of the OPF-BP40 and OPF-BP50 groups when compared with the others that were fabricated (Figure 3A–C). The amount of phosphate released from hydrogels was a result of the interaction of BP concentration and the amount of time left in solution (F35,87 = 1.78, p = 0.0163), with the cumulative release of phosphate after 28 d displaying a strong linear increase along with BP concentration (r2 = 0.91, p = 0.002; Figure 2E).

Figure 3.

The rheological properties of both non-mineralized (A-C) and mineralized (D-F) OPF-BP hydrogels, describing the storage modulus (G’), loss modulus (G”), and viscosity (tan δ; G’/G”) as a function of frequency and degree of BP functionalization (0–50%, BP w/w OPF). Non-mineralized and mineralized hydrogels were then compared at a single frequency (10 rad s−1) across BP concentration (G-I).

3.2. OPF-BP hydrogel mineralization

Calcium mineralization of OPF-BP hydrogels was successfully accomplished through the enzymatic deposition, subsequent uptake, and association of calcium ions with crosslinked BP. Calcium uptake did not noticeably change the physical appearance of hydrogels (Figure 1C), but did lead to a change in the surface topography when viewed under SEM (Figure 2A), with an increased presence of calcium deposits, resembling calcium carbonate crystals, on the surface of hydrogels as BP concentration increased. EDS analysis of the surface displayed a linear trend of increasing Ca:C ratio with BP concentration (r2 = 0.84, p = 0.006), followed by a precipitous drop in the Ca:P ratio (r2 = 0.88, p = 0.003; Figure 2C). Calcium mineralization significantly impacted the storage modulus (F1,378 = 7.62, p=0.006), loss modulus (F1,378 = 3.45, p=0.04), and viscosity (F1,378 = 3.95, p = 0.047), leading to significant shifts in these parameters when compared with non-mineralized samples overall (Figure 3D–F), but not when compared at specific frequencies, such as at 10 rad s−1, as displayed in Figure 3G–I. The amount of calcium absorbed by hydrogels linearly scaled with BP concentration (r2 = 0.97, p < 0.001; Figure 2D), with an excess of 200 μg mg−1 calcium absorbed by the OPF-BP50 group after 3 d. Similarly, the amount of calcium released from hydrogels overtime depended on the interaction of BP concentration and time in solution (F40,102 = 2.91, p<0.001), with the cumulative release of calcium after 21 d linearly increasing with BP concentration (r2 = 0.92, p=0.001; Figure 2F).

3.3. BP and OPF-BP hydrogel cytotoxicity

MC3T3-E1 cell viability decreased when cultured in media containing unreacted BP above concentrations of 20 mM for 4 days (Figure 4C; R2 = 0.27, p <0.01). In contrast, cell viability increased when exposed to the leaching solution of OPF hydrogels crosslinked with BP, both before (Figure 4D; F5,48 = 23.87, p <0.001) and after mineralization with calcium (Figure 4E; F5,48 = 3.58, p = 0.007). Whether or not hydrogels were mineralized did not significantly affect cell viability (F1,95 = 1.65, p = 0.202).

Figure 4.

Confocal images displaying MC3T3-E1 cell viability on non-mineralized (A) and mineralized (B) hydrogels with varying amounts of BP (0–50%, BP w/w OPF) 1, 3, and 7 d after initial cell seeding. Viable cells are stained green while dead cells are stained red. Cell viability (%, normalized to TCP control) after 4 days of culture in media containing unreacted BP monomers (C) or while exposed to the leaching solution from crosslinked OPF-BP hydrogels before (D) and after (E) enzymatic calcium mineralization.

3.4. Osteoblast attachment, proliferation, and differentiation

MC3T3-E1 cells successfully attached to OPF-BP hydrogels, with the greatest cell coverage after one day in culture observed on the OPF-BP30, OPF-BP40, and OPF-BP50 treatments (Figure 4A). However, after seven days, moderate cell growth was observed across all BP treatments, outpacing that seen in the OPF control, with a spread-out morphology observed for osteoblasts on hydrogels with higher BP concentrations (Figure 4A). Measurements of metabolic activity (Figure 5A) and total dsDNA (Figure 5c) over a 21-day period were in agreement that the interaction of BP concentration and time in culture significantly affected cell proliferation (MTS: F20,100 = 5.76, p<0.001; dsDNA: F20,231 = 7.31, p<0.001), with both metrics peaking in the OPF-BP20 and OPF-BP30 groups after 14 d. Similarly, osteogenic differentiation was also affected by this interaction (F20,100 = 4.08, p<0.001), displaying a similar peak in relative ALP activity with an 8-fold increase in the OPF-BP20 treatment after 14 d compared to the OPF, day 1 control (p<0.001; Figure 6A). Osteocalcin expression varied according to the interaction between BP concentration and time (F10,62 = 7.04, p<0.001). The highest relative osteocalcin expression was observed after 21 d in the mineralized OPF-BP30 treatment, representing a 23-fold increase in expression compared to the nonmineralized OPF treatment on day 7 (Figure 7A,B).

Figure 5.

Proliferation of MC3T3-E1 cells on either non-mineralized or mineralized OPF-BP hydrogels, as a function of BP incorporation (0–50%, BP w/w OPF) and time after initial cell seeding (1, 3, 7, 14, or 21 d). Metabolic activity was measured using the MTS assay, reading the optical density (OD) at 490 nm. Total dsDNA was measured using the PicoGreen dsDNA quantification assay. Values represent the mean ± standard error of 3–4 hydrogels per group. * denote timepoints where OPF-BP hydrogels were significantly different from the OPF hydrogel control. # denote timepoints with significant difference between the mineralized and non-mineralized treatments.

Figure 6.

The ALP activity (fold change) of MC3T3-E1 cells on either non-mineralized (A) or mineralized (B) OPF-BP hydrogels, as a function of BP functionalization (0–50%, BP w/w OPF) and time after initial cell seeding (1, 3, 7, 14, or 21 d). ALP activity was normalized to the total protein content of each hydrogel and then compared across treatments, using the non-mineralized OPF treatment at day 1 as a baseline to calculate the fold change. Values represent the mean ± standard error of 3–4 hydrogels per group. * denote timepoints where OPF-BP hydrogels were significantly different from the OPF hydrogel control. # denote timepoints with significant difference between the mineralized and non-mineralized treatments.

Figure 7.

Osteocalcin expression (fold change) of MC3T3-E1 cells on either non-mineralized (A) or mineralized (B) OPF-BP hydrogels, as a function of BP functionalization (0–50%, BP w/w OPF) and time after initial cell seeding (1, 3, 7, 14, or 21 d). Osteocalcin was normalized to the total protein content of each hydrogel and then compared across treatments, using the non-mineralized OPF treatment at day 7 as a baseline to calculate the fold change. Values represent the mean ± standard error of 3–4 hydrogels per group. * denote timepoints where OPF-BP hydrogels were significantly different from the OPF hydrogel control. # denote timepoints with significant difference between the mineralized and non-mineralized treatments.

OPF-BP hydrogel mineralization had a significant impact on the proliferation, differentiation, and osteocalcin expression of MC3T3-E1 cells when compared with non-mineralized treatments. While initial cell coverage was similar between non-mineralized and mineralized hydrogels (Figure 4), by day 7 the cell density observed on OPF-BP30, OPF-BP40, and OPF-BP50 hydrogels outpaced that seen in treatments with less phosphate (Figure 4B). The metabolic activity of cells was significantly impacted by hydrogel mineralization (F1,119 = 132, p <0.001), leading to a significant increase of 31.4% (p=0.001) and 80.6% (p<0.001) in the OPF-BP10 treatment on days 14 and 21, and a 35.4% increase in the OPF-BP20 treatment on day 21 (p<0.001; Figure 5B). Similarly, hydrogel mineralization also had a significant effect on total dsDNA content (F1,460 = 5.32, p<0.001), indicating more cells were present on mineralized OPF-BP10, OPF-BP20, and OPF-BP30 hydrogels when compared with their unmineralized counterparts after 7, 14, and 21 days. Cell differentiation was affected by calcium mineralization (F1,118 = 21.1, p = 0.009), with a 14.3% increase in ALP activity observed on day 14 in the OPF-BP30 treatment (Figure 6B). Hydrogel mineralization also significantly affected osteocalcin expression (F1,71 = 4.76, p = 0.03), leading to a 128% increase in the OPF-BP30 treatment on day 21 (p=0.003), as well as a decrease of 66.6% (p<0.001) and 55.4% (p<0.001) in the 40% and 50% BP treatment on day 21, respectively (Figure 7B).

4. Discussion

Phosphate functionalization of OPF hydrogels resulted in a dose-dependent improvement in osteoblast attachment, proliferation, and differentiation in treatments with BP concentrations less than 930 μmol (OPF-BP30). At BP concentrations above this threshold, MC3T3-E1 cells displayed a significant increase in proliferation and differentiation when compared with the OPF control, but failed to perform as well as treatments with lower BP concentrations after 21 d in culture. Enzymatic calcium mineralization of hydrogels before initial cell seeding significantly improved osteoblast cell proliferation and differentiation when compared with phosphate functionalized treatments, with a 128% increase in osteocalcin expression observed at 21 d in the OPF-BP30 treatment. These results reinforce that phosphate functionalization and calcium mineralization can have a synergistic, positive affect on osteoblast activity, and may play an important role in bone mineral formation, making this approach an exciting strategy for polymeric materials that aim to support bone regeneration.

The use of calcium phosphates to enhance bone growth has been a common practice in medicine since the 1980’s41,42, with classes of drugs like bisphosphonates being used for the treatment of Paget’s disease, osteoporosis, hyperkaliemia of malignancy, osteogenesis imperfect, and inflammation-related bone loss43–52. However, the disadvantages of this approach, including a lack of specificity, low reported levels of bioavailable phosphate32,53, and side effects including osteonecrosis of the jaw54–56, continue to motivate the development of effective alternatives. As a solution, implantable polymeric scaffolding materials coated with calcium phosphates have been developed in an effort to effectively guide and localize bone regeneration9,57,58. However, the use of calcium phosphate coatings also has its disadvantages, including poor long-term adhesion of minerals to scaffold surfaces, resulting in the uneven release or complete loss of bioactive compounds after implantation59,60. This limitation poses a challenge for the adequate release of bioactive compounds needed to support the dynamic process of bone remodeling61–64.

Building on previous work from our laboratory, this study describes an effective alternative to calcium phosphate coatings through the phosphate functionalization and subsequent enzymatic calcification of the biodegradable polymer OPF. To date, phosphate functionalization through the addition of negatively charged phosphate methacrylate groups or other cross-linkable forms of phosphate have been shown to be an effective addition for bone mineralization in both natural and PEG-based materials17,27,28,65–67. Crosslinking OPF with BP, Dadsetan et al. (2012) found that cell proliferation and ALP activity was greatest on OPF hydrogels with a ratio of 20% BP using the human fetal osteoblast (hFOB) cell line, with a significant reduction in cell number after seven days in the BP30 treatment18. Similar results were seen in vivo using the orthotopic defect model in rats, where Olthof et al. (2018) was able to demonstrate that OPF-BP hydrogels functionalized with 20% and 40% w/w BP had a higher bone formation rate and produced more bone volume after 9 weeks than the non-phosphorylated control29. While these results are promising, both of these studies relied on the natural formation of calcium phosphates through nucleation, which can often be slow and environmentally dependent.

Using urease from the legume Canavalia ensiformis, OPF-BP hydrogels in this study were mineralized over the course of three days37, leading to different surface topographies, surface elemental ratios, swelling rations, sol fractions, protein adsorption, and phosphate/calcium release kinetics. The cumulative release of phosphate and calcium ions scaled with hydrogel BP content, resulting in a predictable decay and sustained release of each molecule over the course of 21 d in vitro. In the OPF-BP50 treatment, a burst release of up to 0.4 μmol of phosphate and 12 μg of calcium was observed after the first day, decaying to a rate of ca. 0.1 μmol d−1 of phosphate and 1 μg d−1 of calcium after two weeks.

MC3T3-E1 cell proliferation was measured in this study using both a metabolic (MTS) and DNA-based (PicoGreen) assay (Figure 5). Comparing the two methods, the OPF-BP20 and OPF-BP30 hydrogels consistently supported more cell growth than the other formulations tested, a trend that was also observed after mineralization and is in agreement with confocal imaging. Both methods also reported that the mineralized OPF-BP20 and OPF-BP30 formulations outperformed their non-mineralized counterparts after 7 days, supporting the conclusion that pre-implantation mineralization improves cell proliferation in osteoblasts. However, discrepancies between the two methods were also evident; MTS results reported higher cell proliferation on mineralized OPF-BP40 and OPF-BP50 hydrogels when compared to their non-mineralized counterparts, a result that was not supported by the total DNA assay. Due to the tendency for metabolic assays to overestimate cell number68, it is likely that the DNA-based assay reflects a more accurate representation of cell proliferation on these formulations.

The observed decrease in cell proliferation and differentiation in hydrogel treatments with BP w/w OPF proportions of 40% and 50% is consistent with previous studies18. Given that the concentration of phosphate ions leaching from these hydrogel formulations were below the 10−4 M threshold that other studies have reported as inhibitory to cell growth69,70, it remains unclear why this decrease in cell viability occurs so precipitously. BP in its native form is cytotoxic, dramatically affecting cell viability at concentrations above 20 mM as observed in this study, likely due to the highly reactive nature of the molecules’ methacrylate groups. However, this inhibitory effect was lost when the monomer was crosslinked within the OPF polymer network, as evidenced by the observation that leaching solution from OPF-BP hydrogels actually increases cell viability after 4 days of exposure. Rather than cytotoxicity, one possible explanation for the observed decrease in cell viability is that the Ca/P ratio on the surface of hydrogels decreases as the incorporation of BP increases, indicating that, while more Ca2+ is absorbed, the efficiency of surface binding decreases leading to a lower density of biomineralization.

In addition to the amount of calcium and phosphate released, the morphology, composition, and structure of the biomineralized surface of hydrogels determines the success of pre-osteoblast cell attachment and differentiation71. In this study, calcium mineralization significantly impacted the mechanical properties of hydrogels by shifting the storage modulus, loss modulus, and viscosity of the BP40 and BP50 treatments. This change was also accompanied by a smaller swelling ratio and higher sol fraction, indicating that higher concentrations of BP within the polymer network may interfere with adequate crosslinking, leading to structural instability and a faster rate of degradation. Protein absorption to the surface of hydrogels indicate that the surfaces of the OPF-BP40 and OPF-BP50 treatments do not impart any specific advantage for cell adhesion, and may even be too unstable for adequate coverage during cell seeding, a result which is consistent with confocal imaging taken on days 1 and 3. These results show that, while the inclusion of calcium phosphates into polymer scaffolds may generally increase osteoblast activity, the osteoconductivity of the material is most likely the result of multiple factors working in concert to regulate cellular activity.

5. Conclusion

To overcome the disadvantages of current approaches in bone tissue engineering, the development of biodegradable, osteoconductive polymers with reproducible degradation kinetics that positively interact with bone remodeling are needed. The results of this study suggest that, through phosphate functionalization and enzymatic calcium mineralization, the synthetic polymer oligo[poly(ethylene glycol) fumarate] (OPF) is a promising candidate for use as a bone tissue scaffold that promotes osteogenesis. Of the formulations tested, calcium mineralized OPF-BP hydrogels containing 20% and 30% w/w bis[2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl] phosphate (BP) optimized pre-osteoblast (MC3T3-E1) cell attachment, proliferation, differentiation over the course of 21 days in vitro. These finding suggest that that phosphate functionalization and calcium deposition using OPF hydrogels can work synergistically to promote the process of bone mineralization, providing a promising polymer formulation for inclusion in future animal studies evaluating the efficacy of bone scaffolding materials.

7. Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 AR56212.

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

8. References

- 1.Wozney JM, Seeherman HJ. Protein-based tissue engineering in bone and cartilage repair. Current opinion in biotechnology 2004;15(5):392–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laurencin CT, Ambrosio A, Borden M, Cooper J Jr. Tissue engineering: orthopedic applications. Annual review of biomedical engineering 1999;1(1):19–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banwart JC, Asher MA, Hassanein RS. Iliac crest bone graft harvest donor site morbidity. A statistical evaluation. Spine 1995;20(9):1055–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steinmann JC, Herkowitz HN. Pseudarthrosis of the spine. Clinical orthopaedics and related research 1992(284):80–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niinomi M Metallic biomaterials. Journal of Artificial Organs 2008;11(3):105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou Z, Liu X, Liu Q, Liu L. Evaluation of the potential cytotoxicity of metals associated with implanted biomaterials (I). Preparative Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2008;39(1):81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyle WJ, Simonet WS, Lacey DL. Osteoclast differentiation and activation. Nature 2003;423(6937):337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nerem RM. Tissue engineering: the hope, the hype, and the future. Tissue engineering 2006;12(5):1143–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barrère F, van Blitterswijk CA, de Groot K. Bone regeneration: molecular and cellular interactions with calcium phosphate ceramics. International journal of nanomedicine 2006;1(3):317. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kohane DS, Langer R. Polymeric biomaterials in tissue engineering. Pediatric research 2008;63(5):487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mouriño V, Boccaccini AR. Bone tissue engineering therapeutics: controlled drug delivery in three-dimensional scaffolds. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 2009;7(43):209–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baroli B From natural bone grafts to tissue engineering therapeutics: brainstorming on pharmaceutical formulative requirements and challenges. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences 2009;98(4):1317–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyen MK, Lee DS. Injectable biodegradable hydrogels. Macromolecular bioscience 2010;10(6):563–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kinard LA, Kasper FK, Mikos AG. Synthesis of oligo (poly (ethylene glycol) fumarate). Nature protocols 2012;7(6):1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dadsetan M, Knight AM, Lu L, Windebank AJ, Yaszemski MJ. Stimulation of neurite outgrowth using positively charged hydrogels. Biomaterials 2009;30(23–24):3874–3881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dadsetan M, Szatkowski JP, Yaszemski MJ, Lu L. Characterization of photo-cross-linked oligo [poly (ethylene glycol) fumarate] hydrogels for cartilage tissue engineering. Biomacromolecules 2007;8(5):1702–1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nuttelman CR, Benoit DS, Tripodi MC, Anseth KS. The effect of ethylene glycol methacrylate phosphate in PEG hydrogels on mineralization and viability of encapsulated hMSCs. Biomaterials 2006;27(8):1377–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dadsetan M, Giuliani M, Wanivenhaus F, Runge MB, Charlesworth JE, Yaszemski MJ. Incorporation of phosphate group modulates bone cell attachment and differentiation on oligo (polyethylene glycol) fumarate hydrogel. Acta biomaterialia 2012;8(4):1430–1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jafari M, Paknejad Z, Rad MR, Motamedian SR, Eghbal MJ, Nadjmi N, Khojasteh A. Polymeric scaffolds in tissue engineering: a literature review. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials 2017;105(2):431–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rezwan K, Chen Q, Blaker J, Boccaccini AR. Biodegradable and bioactive porous polymer/inorganic composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2006;27(18):3413–3431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neumann M, Epple M. Composites of calcium phosphate and polymers as bone substitution materials. European Journal of Trauma 2006;32(2):125–131. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ara M, Watanabe M, Imai Y. Effect of blending calcium compounds on hydrolytic degradation of poly (DL-lactic acid-co-glycolic acid). Biomaterials 2002;23(12):2479–2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao W, Hench LL. Bioactive materials. Ceramics international 1996;22(6):493–507. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rea S, Best S, Bonfield W. Bioactivity of ceramic–polymer composites with varied composition and surface topography. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine 2004;15(9):997–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffman AS. Hydrogels for biomedical applications. Advanced drug delivery reviews 2012;64:18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gkioni K, Leeuwenburgh SC, Douglas TE, Mikos AG, Jansen JA. Mineralization of hydrogels for bone regeneration. Tissue Engineering Part B: Reviews 2010;16(6):577–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarvestani AS, He X, Jabbari E. Effect of osteonectin‐derived peptide on the viscoelasticity of hydrogel/apatite nanocomposite scaffolds. Biopolymers: Original Research on Biomolecules 2007;85(4):370–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarvestani AS, He X, Jabbari E. Osteonectin-derived peptide increases the modulus of a bone-mimetic nanocomposite. European Biophysics Journal 2008;37(2):229–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olthof MG, Tryfonidou MA, Liu X, Pouran B, Meij BP, Dhert WJ, Yaszemski MJ, Lu L, Alblas J, Kempen DH. Phosphate Functional Groups Improve Oligo [(Polyethylene Glycol) Fumarate] Osteoconduction and BMP-2 Osteoinductive Efficacy. Tissue Engineering Part A 2018;24(9–10):819–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fleisch H Bisphosphonates in bone disease: from the laboratory to the patient: Elsevier; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fleisch HA. Bisphosphonates: preclinical aspects and use in osteoporosis. Annals of medicine 1997;29(1):55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ezra A, Golomb G. Administration routes and delivery systems of bisphosphonates for the treatment of bone resorption. Advanced drug delivery reviews 2000;42(3):175–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hughes D, MacDonald B, Russell R, Gowen M. Inhibition of osteoclast-like cell formation by bisphosphonates in long-term cultures of human bone marrow. The Journal of clinical investigation 1989;83(6):1930–1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reszka AA, Halasy-Nagy JM, Masarachia PJ, Rodan GA. Bisphosphonates act directly on the osteoclast to induce caspase cleavage of mst1 kinase during apoptosis A link between inhibition of the mevalonate pathway and regulation of an apoptosis-promoting kinase. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1999;274(49):34967–34973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jo S, Shin H, Shung AK, Fisher JP, Mikos AG. Synthesis and characterization of oligo (poly (ethylene glycol) fumarate) macromer. Macromolecules 2001;34(9):2839–2844. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park H, Guo X, Temenoff JS, Tabata Y, Caplan AI, Kasper FK, Mikos AG. Effect of swelling ratio of injectable hydrogel composites on chondrogenic differentiation of encapsulated rabbit marrow mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. Biomacromolecules 2009;10(3):541–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nijhuis AW, Takemoto S, Nejadnik MR, Li Y, Yang X, Ossipov DA, Hilborn J, Mikos AG, Yoshinari M, Jansen JA. Rapid screening of mineralization capacity of biomaterials by means of quantification of enzymatically deposited calcium phosphate. Tissue Engineering Part C: Methods 2014;20(10):838–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quarles LD, Yohay DA, Lever LW, Caton R, Wenstrup RJ. Distinct proliferative and differentiated stages of murine MC3T3‐E1 cells in culture: An in vitro model of osteoblast development. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 1992;7(6):683–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fernandez ES. Johnson: Johnson Transformation. R package version 1.4; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fd Mendiburu. Agricolae: statistical procedures for agricultural research. R package version 1.2–8; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dorozhkin SV. Biphasic, triphasic and multiphasic calcium orthophosphates. Acta biomaterialia 2012;8(3):963–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dorozhkin SV, Epple M. Biological and medical significance of calcium phosphates. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2002;41(17):3130–3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Beek E, Hoekstra M, van De Ruit M, Löwik C, Papapoulos S. Structural requirements for bisphosphonate actions in vitro. Journal of bone and mineral research 1994;9(12):1875–1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rodan GA. Mechanisms of action of bisphosphonates. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology 1998;38(1):375–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shi X, Wang Y, Ren L, Gong Y, Wang D-A. Enhancing alendronate release from a novel PLGA/hydroxyapatite microspheric system for bone repairing applications. Pharmaceutical research 2009;26(2):422–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Green JR, Rogers MJ. Pharmacologic profile of zoledronic acid: a highly potent inhibitor of bone resorption. Drug development research 2002;55(4):210–224. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pavlakis N, Schmidt RL, Stockler MR. Bisphosphonates for breast cancer. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Black DM, Delmas PD, Eastell R, Reid IR, Boonen S, Cauley JA, Cosman F, Lakatos P, Leung PC, Man Z. Once-yearly zoledronic acid for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. New England Journal of Medicine 2007;356(18):1809–1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rauch F, Glorieux FH. Osteogenesis imperfecta, current and future medical treatment. 2005. Wiley Online Library; p 31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Borah B, Ritman EL, Dufresne TE, Jorgensen SM, Liu S, Sacha J, Phipps RJ, Turner RT. The effect of risedronate on bone mineralization as measured by micro-computed tomography with synchrotron radiation: correlation to histomorphometric indices of turnover. Bone 2005;37(1):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Little DG, McDonald M, Bransford R, Godfrey CB, Amanat N. Manipulation of the anabolic and catabolic responses with OP‐1 and zoledronic acid in a rat critical defect model. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 2005;20(11):2044–2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cattalini JP, Boccaccini AR, Lucangioli S, Mouriño V. Bisphosphonate-based strategies for bone tissue engineering and orthopedic implants. Tissue Engineering Part B: Reviews 2012;18(5):323–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grey A, Reid IR. Differences between the bisphosphonates for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Therapeutics and clinical risk management 2006;2(1):77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Greenberg MS. Intravenous bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endodontics 2004;98(3):259–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ruggiero SL, Mehrotra B, Rosenberg TJ, Engroff SL. Osteonecrosis of the jaws associated with the use of bisphosphonates: a review of 63 cases. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery 2004;62(5):527–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dannemann C, Grätz K, Riener M, Zwahlen R. Jaw osteonecrosis related to bisphosphonate therapy: a severe secondary disorder. Bone 2007;40(4):828–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang F, Wolke JGC, Jansen JA. Biomimetic calcium phosphate coating on electrospun poly (ɛ-caprolactone) scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Chemical Engineering Journal 2008;137(1):154–161. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dadsetan M, Guda T, Runge MB, Mijares D, LeGeros RZ, LeGeros JP, Silliman DT, Lu L, Wenke JC, Baer PRB. Effect of calcium phosphate coating and rhBMP-2 on bone regeneration in rabbit calvaria using poly (propylene fumarate) scaffolds. Acta biomaterialia 2015;18:9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saiz E, Goldman M, Gomez-Vega JM, Tomsia AP, Marshall GW, Marshall SJ. In vitro behavior of silicate glass coatings on Ti6Al4V. Biomaterials 2002;23(17):3749–3756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rhee S-H, Tanaka J. Effect of citric acid on the nucleation of hydroxyapatite in a simulated body fluid. Biomaterials 1999;20(22):2155–2160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim CW, Yun Y-P, Lee HJ, Hwang Y-S, Kwon IK, Lee SC. In situ fabrication of alendronate-loaded calcium phosphate microspheres: controlled release for inhibition of osteoclastogenesis. Journal of Controlled Release 2010;147(1):45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Verron E, Khairoun I, Guicheux J, Bouler J-M. Calcium phosphate biomaterials as bone drug delivery systems: a review. Drug discovery today 2010;15(13–14):547–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sheridan M, Shea L, Peters M, Mooney D. Bioabsorbable polymer scaffolds for tissue engineering capable of sustained growth factor delivery. Journal of controlled release 2000;64(1–3):91–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nikkola L Methods for Controlling Drug Release from Biodegradable Matrix and Development of Multidrug Releasing Materials. Tampereen teknillinen yliopisto. Julkaisu-Tampere University of Technology. Publication; 838 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Du C, Cui F, Zhang W, Feng Q, Zhu X, De Groot K. Formation of calcium phosphate/collagen composites through mineralization of collagen matrix. Journal of biomedical materials research 2000;50(4):518–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Suzuki S, Whittaker MR, Grøndahl L, Monteiro MJ, Wentrup-Byrne E. Synthesis of soluble phosphate polymers by RAFT and their in vitro mineralization. Biomacromolecules 2006;7(11):3178–3187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim CW, Kim SE, Kim YW, Lee HJ, Choi HW, Chang JH, Choi J, Kim KJ, Shim KB, Jeong Y-K. Fabrication of hybrid composites based on biomineralization of phosphorylated poly (ethylene glycol) hydrogels. Journal of Materials Research 2009;24(1):50–57. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Quent VM, Loessner D, Friis T, Reichert JC, Hutmacher DW. Discrepancies between metabolic activity and DNA content as tool to assess cell proliferation in cancer research. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine 2010;14(4):1003–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li EC, Davis LE. Zoledronic acid: a new parenteral bisphosphonate. Clinical therapeutics 2003;25(11):2669–2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reinholz GG, Getz B, Pederson L, Sanders ES, Subramaniam M, Ingle JN, Spelsberg TC. Bisphosphonates directly regulate cell proliferation, differentiation, and gene expression in human osteoblasts. Cancer research 2000;60(21):6001–6007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Addison WN, Nelea V, Chicatun F, Chien YC, Tran-Khanh N, Buschmann MD, Nazhat SN, Kaartinen MT, Vali H, Tecklenburg MM. Extracellular matrix mineralization in murine MC3T3-E1 osteoblast cultures: an ultrastructural, compositional and comparative analysis with mouse bone. Bone 2015;71:244–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]