Abstract

The extracranial and intracranial circulations are richly interconnected at numerous locations, a functional connectivity which underlies their impressive capacity for adaptive plasticity in the setting of vasoocclusive disease. While evolutionarily beneficial, these connections can also result in inadvertent communication with the intracranial circulation during embolization of extracranial vessels, potentially resulting in stroke or cranial nerve palsy. While these anastomoses are always present to a certain extent, flow through them occurs under predictable circumstances, and thus embolization of the extracranial vasculature can be performed safely when knowledge of functional anatomy is combined with adherence to basic principles. Herein, we will review the anatomy of known extracranial–intracranial anastomoses and strategies for avoidance of unwanted intracranial embolization. We will also review the vascular supply to cranial nerves most at risk during common neurointerventional procedures, as well as blood supply to mucosal structures.

Keywords: anatomy, endovascular procedures, external carotid artery, interventional radiology

The external carotid artery (ECA) serves as the access route for numerous neurointerventional procedures, most commonly embolization of head and neck tumors, dural arteriovenous fistulae, and treatment of uncontrolled naso- and oropharyngeal bleeding. Injection of embolic material into most ECA branches is generally considered safe due to the redundant blood supply and noneloquent nature of extracranial soft and connective tissue structures. In certain circumstances, however, this assumption is erroneous, the prompt recognition of which is necessary to avert potentially catastrophic complications.

Blood supply to early embryologic neural structures is delivered primarily by axially oriented segmental vessels stemming from the primordial dorsal and ventral aortae. As the embryo develops, longitudinal connections between these segmental vessels form and mature, ultimately becoming the great vessels constituting the adult circulation, specifically the internal carotid, external carotid, and vertebral arteries. 1 Over time, the original segmental links between these longitudinal vessels involute to varying degrees and can uncommonly remain as one of the persistent carotid-vertebrobasilar anastomoses, most commonly the persistent trigeminal artery. 2 Even in patients with “normal” anatomy, these connections are always present to a certain extent, though they are often invisible on formal angiography. These anastomotic channels underlie the cranial circulation's rich collateral network and potential for compensatory plasticity in instances of chronic, and even acute, vascular occlusion. However, these anastomotic channels can result in dangerous communication between the extracranial and intracranial circulations in the setting of embolization procedures. Knowledge of these anastomoses, as well as the circumstances in which blood flow is preferentially directed through them, is essential for the neurointerventionalist. Herein, we will describe the “dangerous” extracranial–intracranial anastomoses through a presentation of illustrative cases. We will also discuss the vascular supply to cranial nerves most relevant to common neurointerventional procedures and blood supply to mucosal structures important for the treatment of epistaxis.

Dangerous Anastomoses

Prior to discussing specific extracranial–intracranial anastomoses, it is worth reviewing the conditions under which these channels can open and become clinically relevant. Increased pressure on the feeding side of the anastomosis, for example, during superselective or distal catheterization and instances in which the catheter is in a wedged position, can preferentially direct flow through these connections, as can increased demand on the receiving side in instances of arterial occlusion. In addition, high-flow pathologies, most commonly dural arteriovenous fistulae or parenchymal arteriovenous malformations, can sump blood through anastomotic connections toward the location of arteriovenous shunting. 3 Recognition of these circumstances and appropriate modification of neurointerventional strategies can greatly enhance procedural safety. Finally, it is important to note that the arterioles constituting these anastomotic connections are generally 50 to 80 µm in diameter. 3 As such, during particle embolization procedures, the use of larger particles (≥150 µm) is generally considered safe and unlikely to result in intracranial embolization due to traversal of angiographically occult anastomoses. On the other hand, slowly polymerizing liquid embolic agents can pass through these connections with ease and their use should thus be employed with extreme caution, or avoided altogether, in the vicinity of known extracranial–intracranial connections.

These dangerous anastomoses can be considered as occurring within three semidiscrete anatomical subnetworks within the broader extracranial and intracranial circulations, specifically the orbital, petrocavernous, and occipital–cervical regions. We will discuss the specific anastomotic connections within each of these networks separately.

Orbital Region

The orbital contents and periorbital tissues are richly vascularized structures. The ophthalmic artery (OA), which typically originates from the supraclinoid internal carotid artery (ICA) and gives rise to the central retinal artery, is unique in that it is the only pial artery with consistent dural and extradural supply. In addition, the dural and extradural arteries with which the OA has anastomotic connections are among those routinely embolized during neurointerventional procedures, and an anatomic understanding of these connections is critical for avoidance of inadvertent extracranial–intracranial communication. The choroidal blush, which is a reliable marker for retinal blood supply and best seen during the capillary phase on lateral angiographic views, is the most important visual cue that denotes significant collateralization with the OA, though its absence on ECA angiography does not necessarily preclude the potential for dangerous extracranial–intracranial communication. In general, most anastomotic connections with the OA occur at or below the level of the sphenoid ridge, and thus the likelihood for unwanted intracranial communication diminishes as one moves distally past the lesser sphenoid wing. While not strictly the subject of this review as it is an anatomic variant as opposed to routinely occurring anastomotic connection, it is worth emphasizing that an OA origin from the middle meningeal artery (MMA) is a strict contraindication to MMA embolization. The following cases depict the most clinically relevant extradural connections with the OA.

Superior Temporal Artery to Ophthalmic Artery

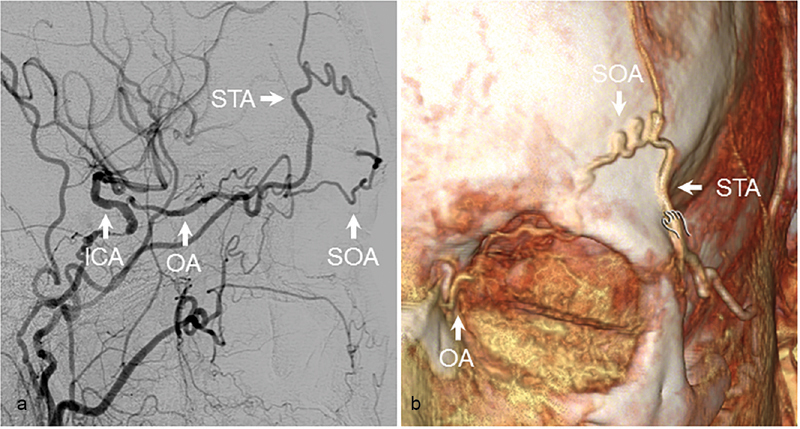

The supraorbital and supratrochlear arteries are terminal branches of the OA that supply structures of the anterior scalp. Together with the supraorbital nerve, the supraorbital artery typically exits the orbit via the supraorbital foramen, while the supratrochlear artery exits the orbit more medially with the supratrochlear nerve. The superficial temporal artery, a terminal branch of the ECA along with the internal maxillary artery (IMAX), bifurcates into frontal and parietal branches, the former of which anastomoses with both supraorbital and supratrochlear arteries. In Fig. 1 , we present angiographic images from a patient with bilateral carotid occlusions. The left ICA was found to reconstitute distal to the occlusion from superior temporal artery supply via the supraorbital artery and OA.

Fig. 1.

Superior temporal artery to ophthalmic artery. ( a ) Angiographic and (b) 3D reconstructions from CT angiography demonstrating reconstitution of the ICA from connections between the STA and OA via the SOA in a patient with left carotid occlusion. ICA, internal carotid artery; OA, ophthalmic artery; SOA, superior orbital artery; STA, superficial temporal artery.

Middle Meningeal Artery to Ophthalmic Artery

The MMA is a frequent source of arterial supply to neurovascular pathology and thus is a common access route for neurointerventional procedures. While embolization of the MMA is generally well tolerated, a known potentially catastrophic complication of this procedure is inadvertent embolization of the intracranial circulation, and/or central retinal artery, secondary to anastomoses with the OA. One potential route of communication is through the recurrent meningeal artery (RMA), which originates from the lacrimal artery shortly after its departure from the OA. After its take-off, the RMA travels back toward the orbital apex and exits the lateral superior orbital fissure to vascularize local dura mater, where clinically relevant communication with the MMA can occur. An additional route of communication between the OA and ECA is through the zygomaticotemporal artery, which departs from the lacrimal artery as it courses along the upper border of the lateral rectus muscle toward the lacrimal gland. This artery exits the orbit through the zygomaticotemporal foramen to reach the temporal fossa where it connects with the deep temporal arteries originating from the IMAX.

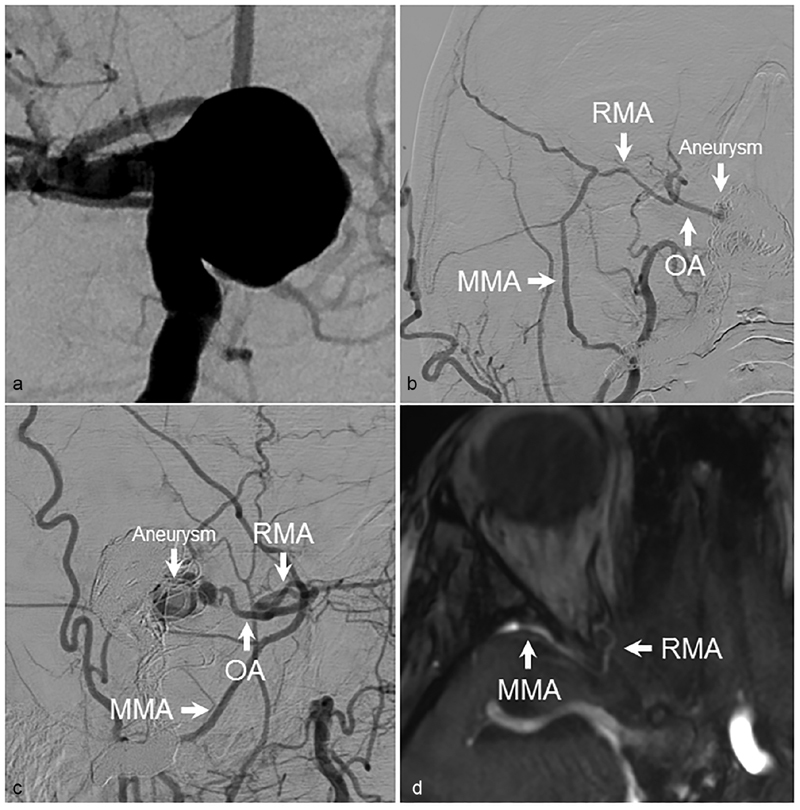

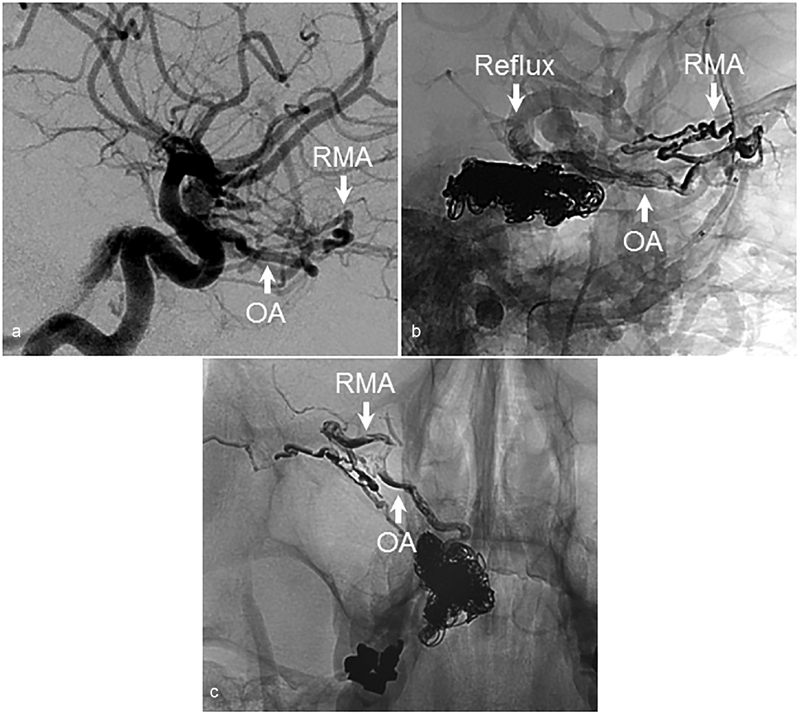

In Fig. 2 , we present a case of a giant supraclinoid artery aneurysm treated with carotid occlusion. ECA angiography performed after embolization demonstrated persistent filling of the aneurysm from the OA, which filled through its communication with the MMA via the RMA. Images from magnetic resonance angiography demonstrate the close proximity of the RMA to the MMA in the region of the superior orbital fissure ( Fig. 2 ). In a second case, a patient presented with an indirect carotid-cavernous fistula fed predominantly by branches of the IMAX. At another institution, the patient underwent combined coil embolization of the cavernous sinus and liquid embolization of feeding IMAX branches. The procedure was complicated by complete right-sided visual loss, and postoperative angiography demonstrated embolization of the OA through its communication with MMA via the RMA; embolic material could be as far distally as the right ICA bifurcation ( Fig. 3 ). This case reinforces the dangers associated with liquid embolization in the vicinity of known extracranial–intracranial anastomoses.

Fig. 2.

Residual filling of supraclinoid aneurysm. ( a ) AP angiographic images demonstrating a large supraclinoid ICA aneurysm. After treatment of the aneurysm with carotid sacrifice, residual aneurysm filling from anastomotic connections between the MMA and OA via the RMA could be seen on ( b ) AP and ( c ) lateral views. ( d ) The anastomotic connection between the MMA and RMA could be seen on MR angiography. AP, anteroposterior; ICA, internal carotid artery; OA, ophthalmic artery; MMA, middle meningeal artery; RMA, recurrent meningeal artery.

Fig. 3.

Inadvertent ICA embolization during treatment of carotid-cavernous fistula with a liquid embolic agent. ( a ) Lateral angiographic images demonstrating an indirect carotid-cavernous fistula. Note the robust RMA. The fistula was treated with a combination of coil embolization of the cavernous sinus through a transvenous route and embolization of IMAX branches with liquid embolic agent. ( b ) Lateral and ( c ) anteroposterior anatomic views demonstrating reflux into the OA and ICA via the RMA. AP, anteroposterior; ICA, internal carotid artery; OA, ophthalmic artery; RMA, recurrent meningeal artery.

Petrocavernous Region

Extracranial–intracranial anastomoses in the petrocavernous region can be further subdivided as occurring in the petrous, clival, and cavernous sinus areas, though there is significant overlap in the anastomotic pathways of these regions.

Petrous Area

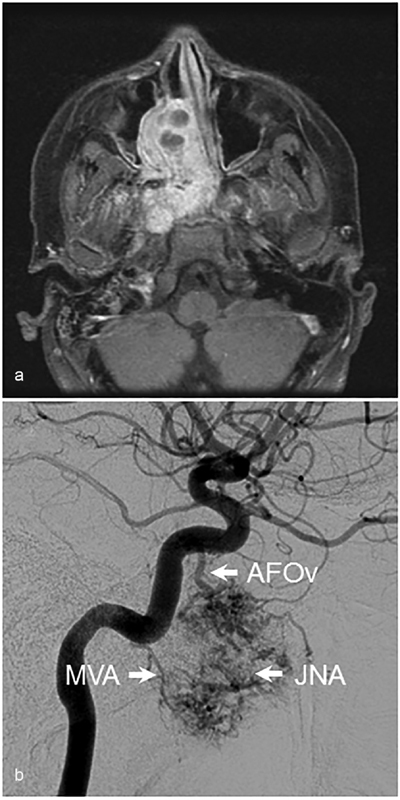

The petrous ICA gives off relatively few and somewhat inconstant branches, which include the caroticotympanic, mandibular, and vidian arteries. When it arises from the petrous ICA, the vidian artery exits the skull through the foramen lacerum and courses toward the pterygopalatine fossa, where it communicates with branches of the distal IMAX. Along its course, the vidian artery provides blood to both naso- and oropharyngeal mucosa, which results in communication with mucosal branches of the ascending pharyngeal artery (APhA) and accessory meningeal arteries, the latter of which is a more proximal branch of the IMAX. Finally, via the arteries of the foramen rotundum and ovale, the vidian artery can anastomose with the inferolateral trunk (ILT) of the cavernous ICA. 4 These connections are best illustrated in the setting of pathology causing branch hypertrophy, which can occur in the setting of a juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma ( Fig. 4 ). The caroticotympanic artery originates from the petrous ICA and enters the middle ear where it anastomoses with the inferior tympanic branch of the APhA; this connection forms the basis of the uncommon aberrant carotid artery variant in which the APhA essentially reconstitutes the ICA in the setting of cervical ICA agenesis. 5 The mandibular artery, which can originate with the vidian artery from a common trunk, exits the temporal bone inferiorly to supply pharyngeal structures and also connect with mucosal APhA branches.

Fig. 4.

Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. ( a ) Axial T1-weighted contrast-enhanced image demonstrating a large JNA of the skull base. ( b ) Arterial blood supply to the tumor from the mandibulovidian artery (MVA) and artery of foramen ovale (AFOv) is seen on lateral angiographic images. JNA, juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma.

Clival Area

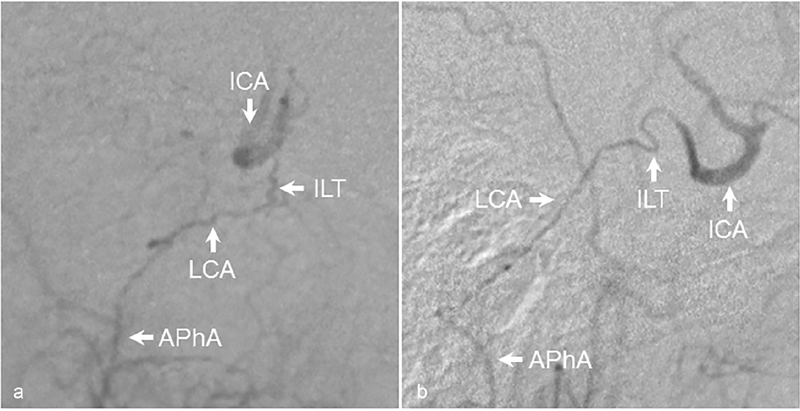

Extracranial–intracranial anastomoses in the vicinity of the clivus occur through connections between the descending clival branches of both ILT and meningohypophyseal trunks (MHT) and ascending branches of the neuromeningeal trunk of the APhA. These connections are demonstrated in a patient with a chronic right ICA occlusion with reconstitution from the APhA ( Fig. 5 ).

Fig. 5.

Reconstitution of ICA through the lateral clival artery. ( a ) AP and ( b ) lateral angiographic images demonstrating reconstitution of the ICA from anastomotic connections between the APhA and ILT via the lateral clival artery in a patient with proximal right carotid occlusion. AP, anteroposterior; APhA, ascending pharyngeal artery; ICA, internal carotid artery; ILT, inferolateral trunk; LCA, lateral clival artery.

Cavernous Area

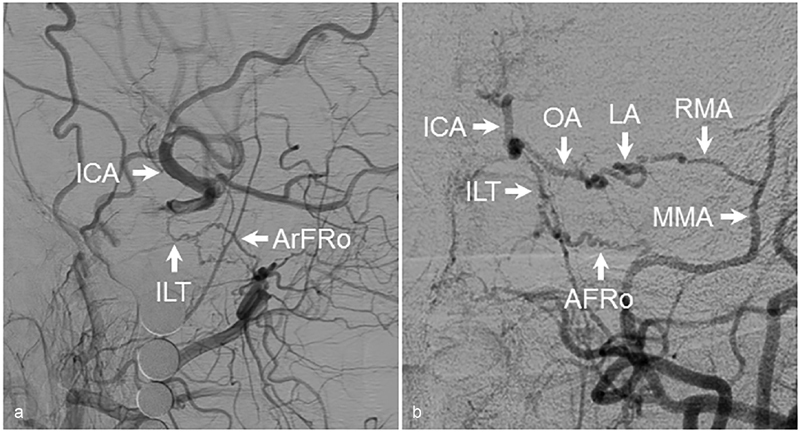

The highest density of extracranial–intracranial communications within the broader petrocavernous region occurs in the vicinity of the cavernous sinus through extracranial connections with the ILT and MHT. The potential anatomic configurations of the ILT are myriad, but in general anterior, posterior, and superior branches have been described. The anterior branch travels forward to the superior orbital fissure to provide vascular supply to cranial nerves and also make connections to the RMA and MMA. The posterior branch vascularizes the second and third divisions of the trigeminal nerve via the arteries of foramen rotundum and ovale, respectively, though the artery of foramen rotundum often originates from the anterior branch. Regardless of their site of origin, these arteries are typically in hemodynamic balance with similarly named branches of the IMAX and are a source of extracranial–intracranial connection. Finally, the superior branch, which is the most inconstant, provides vascular supply to the cavernous sinus roof and connects with cavernous sinus branches of the MMA. 6 7 Relevant branches of the MHT include the marginal tentorial artery (also known as the artery of Bernasconi–Cassinari) coursing along the tentorial incisura, along which path this artery can anastomose with the petrosquamosal branch of the MMA. 8 Examples of ICA reconstitution via ILT branches, specifically the artery of foramen rotundum, in the setting of ICA occlusion can be seen in Fig. 6 .

Fig. 6.

Reconstitution of the ICA from the ILT. ( a ) Lateral angiographic images demonstrating reconstitution of the right ICA from connections between the IMAX and ILT via the artery of foramen rotundum. ( b ) A different case again demonstrating left ICA reconstitution via the artery of foramen rotundum. Also seen is reconstitution from the MMA via the RMA and lacrimal arteries. AFRo, artery of foramen rotundum; AP, anteroposterior; ICA, internal carotid artery; ILT, inferolateral trunk; LA, lacrimal artery; OA, ophthalmic artery; MMA, middle meningeal artery; RMA, recurrent meningeal artery.

Occipital–Cervical Region

Owing to the segmental origins of the extracranial and intracranial circulations, the vertebral arteries, and hence the intracranial posterior circulation, have numerous interconnections with branches of the ECA and other longitudinal vessels of the neck, specifically APhA, occipital artery (OccA), and ascending and deep cervical arteries.

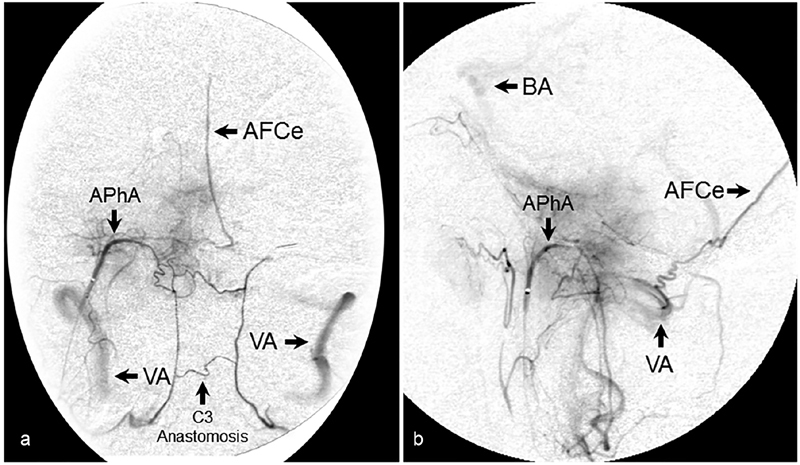

Ascending Pharyngeal Artery to Vertebral Artery

The APhA typically originates from the posterior wall of the ECA soon after the carotid bifurcation and ascends directly superiorly until its division into pharyngeal and neuromeningeal trunks. The former travels anterosuperiorly to supply structures of the pharynx, while the latter travels posterosuperiorly and ultimately divides into jugular and hypoglossal branches supplying the dura and cranial nerves of their respective neural foramina. Prior to this division, the neuromeningeal trunk gives off one or two musculospinal branches feeding the adjacent cervical musculature that form extensive connections with the vertebral arteries. Another route of communication with the vertebral arteries is through the prevertebral branch, which takes off from the hypoglossal trunk and descends through the foramen magnum to connect with the odontoid arcade, an anastomotic network outlining the odontoid process formed by bilateral prevertebral branches and segmental arteries emanating from the vertebral arteries ( Fig. 7 ). These connections are fairly constant, and thus caution should be employed whenever embolizing the APhA to avoid unwanted communication with the intracranial posterior circulation.

Fig. 7.

Odontoid arcade. ( a ) AP and ( b ) lateral angiographic images following selective catheterization and injection of the APhA demonstrating filling of the odontoid arcade and vertebrobasilar system from the prevertebral branch of the APhA. Also seen is filling of the artery of the falx cerebelli. AFCe, artery of falx cerebelli; AP, anteroposterior; APhA, ascending pharyngeal artery; BA, basilar artery; VA, vertebral artery.

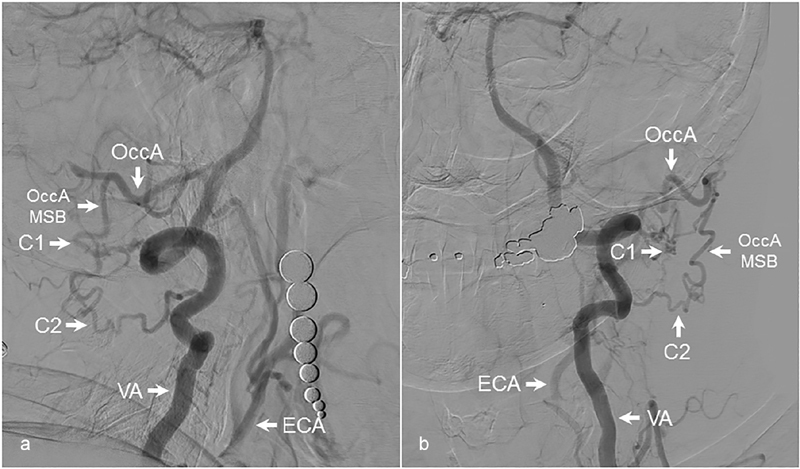

Occipital Artery to Vertebral Artery

After branching from the ECA, the OccA travels posteriorly along the inferolateral skull base to supply the musculature of the upper posterior cervical and suboccipital regions. It has a roughly horizontal orientation as it travels between the mastoid and transverse process of the atlas, along which path it makes interconnections with the vertebral artery through segmental arteries of C1 and C2. These connections are fairly robust and serve as a frequent source of carotid reconstitution in the setting of proximal occlusion ( Fig. 8 ). An additional anastomotic route is through the stylomastoid branch of the OccA, which enters into the stylomastoid foramen and connects with branches of the posterior meningeal artery originating from the vertebral artery.

Fig. 8.

Reconstitution of carotid artery from the occipital artery. ( a ) Lateral and ( b ) AP angiographic images demonstrating reconstitution of an occluded left common carotid artery from anastomotic connections between the VA and OccA. The C1 and C2 segmental arteries from the VA are seen to connect with the musculospinal branch of the OccA, leading to carotid reconstitution. AP, anteroposterior; C1, C1 segmental artery; C2, C2 segmental artery; ECA, external carotid artery; OccA, occipital artery; OccA MSB, musculospinal branch of occipital artery; VA, vertebral artery.

Ascending and Deep Cervical Artery to Vertebral Artery

The ascending and deep cervical arteries are longitudinal vessels of the neck that originate from the thyro- and costocervical trunks, respectively. As they course parallel to the vertebral artery, numerous interconnections between these vessels are made by cervical radicular arteries, with important clinical implications. In instances of proximal vertebral artery occlusion, the distal artery is often reconstituted by one or both of these arteries ( Fig. 9 ). Embolization of either ascending or deep cervical arteries should thus be performed with caution due to the risk of inadvertent vertebral artery embolization. Finally, it is important to note that the anterior spinal artery runs longitudinally along with the vertebral and ascending and deep cervical arteries, and thus is part of the same segmental anastomotic network. Recognition of anterior spinal artery filling during neurointerventional procedures is critical to avoid catastrophic spinal cord infarction during embolization procedures.

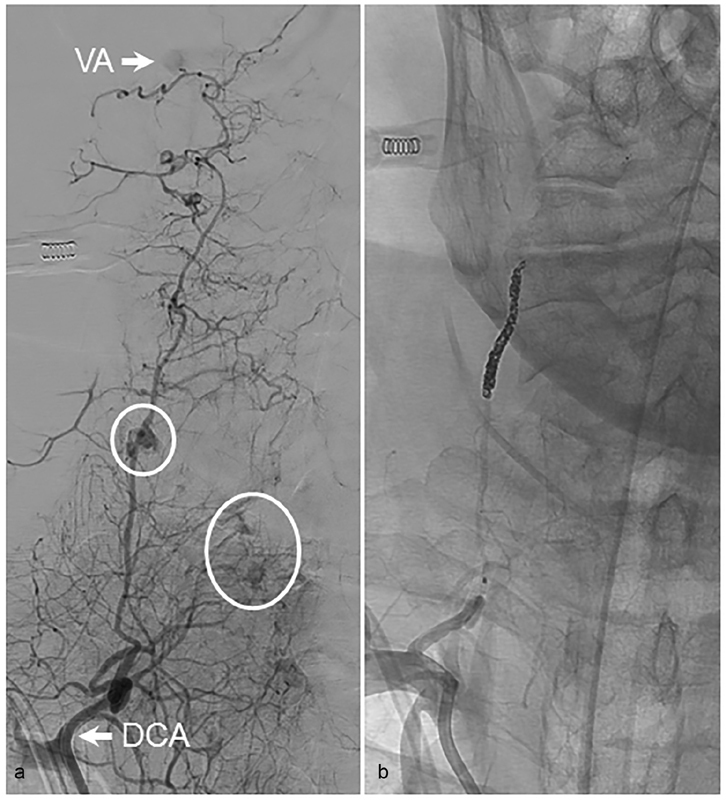

Fig. 9.

Connections between the deep cervical and vertebral arteries. ( a ) AP views following catheterization and injection of the DCA demonstrating active extravasation (circles) from branches of the DCA in a patient with a history of head and neck cancer. Flash filling of the VA is seen (arrow). ( b ) The patient was treated with a combination of coil embolization of the mid- to distal DCA followed by particle embolization with polyvinyl alcohol particles. AP, anteroposterior; DCA, deep cervical artery; VA, vertebral artery.

Cranial Nerve Vascular Supply

While familiarity with the vascularization of all cranial nerves is obviously important, the blood supply to certain cranial nerves and their subdivisions is particularly relevant to a discussion of complication avoidance strategies in extracranial embolization procedures, specifically the fifth, seventh, and lower cranial nerves (IX–XII). As opposed to providing an exhaustive description of cranial nerve supply, we will limit our discussion to cranial nerve segments with predominantly extracranial supply.

Trigeminal Nerve

The maxillary and mandibular divisions of the trigeminal nerve egress from the Gasserian ganglion and pass through foramen rotundum and ovale, respectively. These segments are supplied by the corresponding arteries of foramen rotundum and ovale that originate from branches of the ILT, but are also in hemodynamic balance with IMAX branches of the same name, which in many instances provides the dominant supply to these nerve segments. Embolization of the IMAX thus carries the risk of incurring facial numbness in the maxillary and mandibular nerve distributions. Also noteworthy is the inferior alveolar artery, which originates from the proximal IMAX and runs in the mandibular canal alongside the inferior alveolar nerve, a branch of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve that provides sensation to the lower teeth. Numbness in this distribution is thus another potential complication of IMAX embolization.

Facial Nerve

The vascular supply to the tympanic and mastoid segments of the facial nerve is from an anastomotic network of arteries originating from the extracranial circulation termed the “facial arcade.” The predominant supply is from the petrosquamosal branch of the MMA, with additional supply from the posterior auricular artery via the stylomastoid branch, though this vessel can also take off from the horizontal portion of the OccA.

Lower Cranial Nerves

The lower cranial nerves (9–12) receive significant blood supply from the neuromeningeal trunk of the APhA via the jugular and hypoglossal branches. Prior to its entry into the foramen magnum, the previously mentioned musculospinal branch of the neuromeningeal trunk also vascularizes the accessory nerve. To illustrate the potential pitfalls of APhA embolization, we present a case of a hypoglossal palsy following an embolization procedure with a liquid embolic agent ( Fig. 10 ).

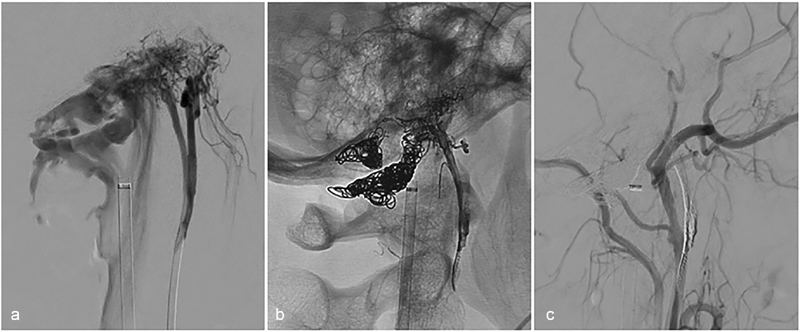

Fig. 10.

Hypoglossal palsy following treatment of condylar dural arteriovenous fistula (dAVF). ( a ) A patient with disabling pulsatile tinnitus was found to have a condylar dAVF fed primarily by the neuromeningeal trunk of the ascending pharyngeal artery. ( b ) Anatomic and ( c ) angiographic lateral images demonstrating obliteration of the dAVF following a combined transvenous and transarterial embolization with coils and liquid embolic agent. The patient awoke with a right-sided hypoglossal nerve palsy that improved over time.

Nasal and Oral Blood Supply

Embolization of ECA branches vascularizing the structures of the nose and mouth for the treatment of uncontrolled bleeding is generally well tolerated due to the extensive collateral network of these tissues. A serious, yet fortunately rare, complication of arterial embolization in these regions is tissue necrosis. We will discuss the vascular supply of both the nose and tongue and associated mucosa and briefly review the literature on the incidence of and risk factors for tissue necrosis after embolization.

Nose and Nasopharyngeal Mucosa

The nose and associated mucosa receives blood supply from both the intracranial and extracranial circulations. The intracranial supply is from the OA via the anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries, which descend through the cribriform plate to vascularize the structures of the superior nasal cavity. From the extracranial circulation, the predominant arterial supply comes from the sphenopalatine artery, which derives from the IMAX in the pterygopalatine fossa. The sphenopalatine artery exits the pterygopalatine fossa via the sphenopalatine foramen and enters the nasal cavity just posterosuperiorly to the middle nasal concha, after which it bifurcates into posterolateral and posterior medial, or septal, branches. Additional nasal arterial supply is from the greater palatine artery, a branch of the descending palatine artery which vascularizes the nasal septum, and superior labial artery, which is a terminal branch of the facial artery.

Embolization of ECA branches for the treatment of intractable epistaxis is now a commonplace procedure. 9 In general, unless a clear source of extravasation is identified, endovascular treatment of epistaxis involves embolization of some combination of the sphenopalatine, greater palatine, and distal facial arteries. The risk of tissue necrosis associated with isolated, unilateral embolization of IMAX branches appears to be minimal, 10 though it has been reported. 11 The authors of this study speculated that this particular case may have complicated by a heavy smoking habit and poor oral hygiene in the patient, along with concomitant treatment with nasal packing, which may have further compromised collateral blood flow. There are multiple series suggesting that bilateral IMAX embolization is generally well tolerated, even when performed in combination with unilateral facial artery embolization, 10 12 13 though nasal packing after bilateral IMAX should be performed judiciously and for as little time as possible as it may dangerously compromise collateral mucosal blood flow. 14 The risk of soft-tissue complications associated with embolization of bilateral IMAX and facial arteries appears to be significant, 12 and thus should be avoided if possible. In instances of recurrent epistaxis after initial embolization, it is important to assess for a significant contribution from the intracranial circulation. In such cases, the patient is likely better suited for open surgical treatment and ligation of the offending artery.

Tongue and Oropharyngeal Mucosa

The tongue receives blood supply primarily from the lingual arteries, each of which provides collateral supply to the contralateral artery. Embolization of the lingual artery is most commonly performed in instances of posttonsillectomy bleeding or pseudoaneurysm 15 16 17 or uncontrolled hemorrhage from oropharyngeal carcinoma. 18 19 Unilateral embolization is generally well tolerated due to the collateral supply, but bilateral lingual artery embolization is not advisable due to risk of tongue necrosis, particularly distally where collateral supply is diminished.

Conclusions

Embolization of the branches of the extracranial circulation allows for the treatment of a vast array of cerebrovascular pathology. While generally safe, the major risks of these procedures are due to the potential for inadvertent communication with the intracranial circulation via small anastomoses. Familiarity of the anatomic location of these connections and the circumstances during which blood flow is preferentially directed through them is essential for safe and effective neurointerventional practice.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None declared.

References

- 1.Lasjaunias P, Berenstein A, Karel Ter Brugge K. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media; 2001. Clinical Vascular Anatomy and Variations. 2nd ed. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uchino A, Sawada A, Takase Y, Kudo S. MR angiography of anomalous branches of the internal carotid artery. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181(05):1409–1414. doi: 10.2214/ajr.181.5.1811409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geibprasert S, Pongpech S, Armstrong D, Krings T. Dangerous extracranial-intracranial anastomoses and supply to the cranial nerves: vessels the neurointerventionalist needs to know. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30(08):1459–1468. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osborn A G. The vidian artery: normal and pathologic anatomy. Radiology. 1980;136(02):373–378. doi: 10.1148/radiology.136.2.7403513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yanmaz R, Okuyucu Ş, Burakgazi G, Bayaroğullari H. Aberrant internal carotid artery in the tympanic cavity. J Craniofac Surg. 2016;27(08):2001–2003. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000003080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lasjaunias P, Moret J, Mink J. The anatomy of the inferolateral trunk (ILT) of the internal carotid artery. Neuroradiology. 1977;13(04):215–220. doi: 10.1007/BF00344216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salaud C, Decante C, Ploteau S, Hamel A. Implication of the inferolateral trunk of the cavernous internal CAROTID artery in cranial nerve blood supply: anatomical study and review of the literature. Ann Anat. 2019;226:23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2019.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris F S, Rhoton A L. Anatomy of the cavernous sinus. A microsurgical study. J Neurosurg. 1976;45(02):169–180. doi: 10.3171/jns.1976.45.2.0169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brinjikji W, Kallmes D F, Cloft H J. Trends in epistaxis embolization in the United States: a study of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample 2003-2010. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;24(07):969–973. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2013.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen J E, Moscovici S, Gomori J M, Eliashar R, Weinberger J, Itshayek E. Selective endovascular embolization for refractory idiopathic epistaxis is a safe and effective therapeutic option: technique, complications, and outcomes. J Clin Neurosci. 2012;19(05):687–690. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2011.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishimoto K, Minoda R, Yoshida R, Hirai T, Yumoto E. A case of periodontal necrosis following embolization of maxillary artery for epistaxis. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2016;2016:6.467974E6. doi: 10.1155/2016/6467974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gottumukkala R, Kadkhodayan Y, Moran C J, Cross W T, III, Derdeyn C P. Impact of vessel choice on outcomes of polyvinyl alcohol embolization for intractable idiopathic epistaxis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;24(02):234–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson A E, McAuliffe W, Phillips T J, Phatouros C C, Singh T P.Embolization for the treatment of intractable epistaxis: 12 month outcomes in a two centre case series Br J Radiol 201790(1080):2.0170472E7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guss J, Cohen M A, Mirza N. Hard palate necrosis after bilateral internal maxillary artery embolization for epistaxis. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(09):1683–1684. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e318093ee8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hassan F, Younes A, Rifai M. Endovascular embolization of post-tonsillectomy pseudoaneurysm: a single-center case series. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2019;42(04):528–533. doi: 10.1007/s00270-018-2131-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levy E I, Horowitz M B, Cahill A M. Lingual artery embolization for severe and uncontrollable postoperative tonsillar bleeding. Ear Nose Throat J. 2001;80(04):208–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Cruijsen N, Gravendeel J, Dikkers F G. Severe delayed posttonsillectomy haemorrhage due to a pseudoaneurysm of the lingual artery. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;265(01):115–117. doi: 10.1007/s00405-007-0391-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Z P, Meng J, Wu H J, Zhang J, Gu Q P. [Application of superselective lingual artery embolization in treatment of severe hemorrhage in patients with carcinoma of tongue] Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2018;53(06):425–427. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1002-0098.2018.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Y F, Lo Y C, Lin W C et al. Transarterial embolization for control of bleeding in patients with head and neck cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;142(01):90–94. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]