To the Editor, in a prospective cohort study, Snekvik et al. (2017) observed that obesity doubles the incidence risk for psoriasis. This finding may be attributable to the inflammatory role of adipokines: adipose-tissue associated hormones including resistin, leptin, adiponectin, and others. Resistin induces inflammatory markers, including TNF-alpha and IL-6 (Johnston et al. 2008). Independent associations have been reported between psoriasis, elevated serum resistin levels, and cardiovascular disease (CVD) (Muse et al. 2015; Huang et al. 2015; Takahashi et al. 2013; Pina et al. 2015). Furthermore, resistin levels are elevated in hypertensive patients (Zhang et al.2017; Papadopoulos Dimitrios P. et al. 2007) and are positively correlated with systolic blood pressure (SBP) (Norata et al. 2007; Makni et al. 2013), suggesting resistin may be a risk factor for hypertension, or vice versa. Hypertension, adipocyte activation, resistin recruitment of TNF/IL-6 and subsequent skin inflammation may lead to psoriasis intensification in susceptible cohorts. Resistin, therefore, is a possible link between psoriasis and increased cardiovascular risk.

We initially examined the correlation between resistin levels and psoriasis severity (expressed as Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score) in a primary patient cohort identified through the Murdough Family Center for Psoriasis. Resistin, leptin, HDL, and LDL levels in the serum of these patients were measured. We included only those participants with quantified resistin levels (n=100). In Figure 1, correlation between PASI and resistin levels are shown, with outliers winsorized to the 5th and 95th percentiles (Ghosh and Vogt 2012). Although outliers were found, assessment of all other measures of these patients were within standard levels for our cohort. Therefore we have presented all resistin and PASI data and probed for whether or not this relationship may be modified by covariates including: sex, race, smoking, atherosclerosis status, age, BMI, LDL/HDL ratio, and SBP (transformed from continuous to a binary variable based on median SBP (normal: <131 mmHg, high: >131mmHg)). We have depicted this data and correlation analysis between PASI and resistin stratified by systolic blood pressure category. Supplementary Figure 1 (S1) depict resistin-PASI relationship for those with 1) Low SBP <131mmHg (n=50), 2) High SBP > 131mmHg (n=50), and combined, with scatter representing observed data and solid colored lines representing unadjusted trend lines.

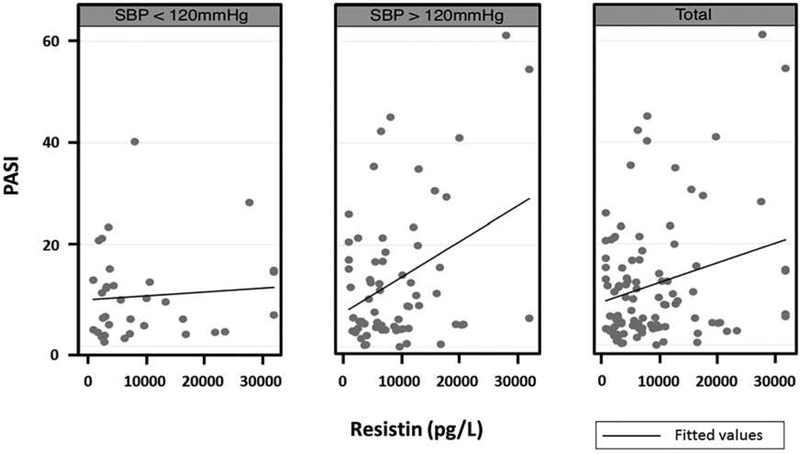

Figure 1:

PASI-resistin relationship stratified by systolic blood pressure category. Graphs depict resistin-PASI relationship for those with 1) Low SBP <120mmHg (n=34), 2) High SBP > 120mmHg (n=66), and 3) all patients (n=100), with scatter representing observed data and solid lines representing unadjusted trend lines. Outliers were winsorized to the 5th and 95th percentiles (Ghosh 2012).

Table 1 (column 1) summarizes patient characteristics. Median PASI score was 7.95 [3.6–15.5]. Median resistin was 6,362.6 [2,883–12,079] pg/L. Mean SBP was 128.1 + 16.8 mmHg/ml. The median SBP was 131 mmHg/ml. The median resistin in the non-hypertensive group was 6,012.8 pg/L compared to a median resistin of 6,750.7 pg/L in the hypertensive group (p=0.39, Wilcoxon test).

Table 1.

Multivariable analyses of PASI-resistin association.

| Characteristic (n=100) | Descriptive Median (IQR) or N% | Adjusted Model 12 | Adjusted Model 23 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P value | P value | ||||

| PASI | 7.95 (3.6 – 15.5) |

||||

| Resistin (pg/L) | 6362.62 (2883 – 12079) |

<0.0001 | 0.562 | ||

| Age (Years) | 46.2 (33.4 – 58.1) |

0.117 | 0.114 | ||

| Female | 48.0% | 0.057 | 0.064 | ||

| Caucasian | 87.0% | -- | -- | ||

| Smoking | 38.0% | -- | -- | ||

| Current use of ACE inhibitors | 14.0% | -- | -- | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.8 (24.3 – 34.4) |

-- | -- | ||

| Atherosclerosis1 | 60.7% | -- | -- | ||

| Psoriatic Arthritis | 14% | -- | -- | ||

| SBP (mmHg) | 131 (115.5–139) |

-- | -- | ||

| High Systolic Blood Pressure (>131 mmHg) | 50% | 0.030 | 0.741 | ||

| Resistin * SBP category (>131mmHg vs. <131mmHg) | -- | -- | 0.024 | ||

| LDL/HDL Ratio | 2.3 (1.8 – 3.0) | -- | -- | ||

Abbreviations: SBP: systolic blood pressure; ACE: angiotensin converting enzyme; BMI: body mass index; LDL: low-density lipids; HDL: high-density lipids; CI: confidence interval

Data regarding atherosclerosis status was available in 89% of the patients.

Model 1 was determined based on backward selection of covariates and adjusts for sex (male vs. female), systolic blood pressure category (>131 mmHg vs. <131mmHg), and age.

Model 2 was determined based on backward selection of covariates and adjusts for sex (male vs. female), systolic blood pressure category (>131 mmHg vs. <131mmHg), age, and interaction term of resistin*SBP category

Multivariable analysis revealed a positive relationship between resistin and PASI score (p<0.0001) after adjusting for age, sex, and SBP (Table 1, adjusted model 1), supporting evidence of an association between resistin and psoriasis severity.

Because previous findings demonstrated that psoriatic patients are more likely to develop hypertension, and that hypertensive patients have elevated resistin levels, we were also interested in exploring whether SBP influenced the resistin-PASI relationship (Zhang et al. 2017; Papadopoulos Dimitrios P. et al. 2007; Armstrong, Harskamp, and Armstrong 2013; Qureshi et al. 2009)). To determine if the PASI-resistin relationship varied between hypertensives and non-hypertensives, we included an interaction term to test for effect modification by SBP in our multivariable model:

Covariates that remained statistically significant at the α=0.10 level were sex and the interactive variable of resistin and binary SBP (Table 1, adjusted model 2). These findings suggest that SBP is an effect modifier on the relationship between PASI and resistin in our cohort. The model indicates that among those with low/normal SBP, every 10,000 pg/L increase in resistin is associated with a 0.9-point increase in PASI score (covariates held constant). By contrast, among those with high SBP, a 10,000 pg/L increase in resistin is associated with a 5.4-point increase in PASI score (covariates held constant), a 6-fold difference.

These findings suggest that resistin is positively associated with PASI in our cohort, and that this relationship is augmented by SBP. Conversely, in patients with high blood pressure, increasing PASI severity leads to elevated resistin levels (results not shown), which may mark a population that needs additional cardiovascular attention. This demonstrates the importance of exploring interaction terms to assess whether the effect of an exposure varies across different groups (Corraini et al. 2017; Gail and Simon, 1985). Effect modification assesses heterogeneity across cohorts which may be used to inform treatments and research (Wang et al. 2007). For example, pravastatin’s efficacy in reducing coronary events was greater in patients with elevated baseline LDL (Sacks et al. 1996; Wang et al. 2007). It is particularly important for relationships involving overlapping pathways, such as that between psoriasis and cardiovascular risk (Norata et al. 2007; Makni et al. 2013). In the search for cardiovascular risk biomarkers, interaction term analyses may indicate that psoriasis patients cannot be treated as one group, revealing endotypes with different risks/needs.

Thus, in the psoriasis subset with hypertension, resistin elevation appears to associate with more intense psoriasis expression and may biomark a higher CVD risk population via adipocytokine-mediated inflammation. One limitation of our study is in its cross-sectional nature; therefore, the association of the interaction term of resistin and SBP with psoriasis disease severity warrants further research into biomarkers of CVD in psoriasis. Furthermore, these findings are purely correlative, not causative, and demand further study. The findings presented here build on prior work on CVD-psoriasis biomarkers which demonstrated that myeloperoxidase (MPO), a pro-inflammatory hemeprotein associated with CVD events, is elevated 2.5-fold in psoriasis patients (Cao et al. 2013; Dilek et al. 2016). We contend that resistin and SBP are additional biomarkers to consider for cardiovascular risk among psoriasis patients.

Data came from a psoriasis prevalence data set from University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center and the Murdough Family Center for Psoriasis, Cleveland, Ohio with data on 276 individuals with skin disorders. Study participants completed a detailed questionnaire including socio-demographics, smoking history, current medications and treatments, psoriatic arthritis, and cardiovascular disease. Resistin, leptin, HDL, and LDL levels in serum were measured. We included only those participants with quantified resistin levels (n=100).

Participant characteristics were reported as medians with interquartile ranges for non-parametric variables and as means with standard deviations for parametric variables. Proportions were reported for binary variables. Univariate regression was performed using independent t-tests to test each covariate against PASI score at a significance level of α=0.10. Potential covariates were selected based on existing literature and backward selection using Akaike’s information criteria (AIC) to reduce overfitting. Model diagnostics included independence of residuals, heteroscedasticity, multicollinearity, and influential outliers. Based on existing literature, we were interested in potential effect modification of SBP on the relationship between PASI score and resistin. For clinical interpretability, we transformed SBP from a continuous to a binary variable.

As the study is exploratory in nature, p-values are reported without correction for multiple testing. All analyses were performed in Stata 14 (College Station, TX).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Ming Li for her statistical support.

Funding Acknowledgement

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers T32AR007569 and P50AR070590. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This study was supported through funding from the Murdough Family Center for Psoriasis and Skin Diseases Research Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy concerns of research participants.

Ethics Approvals

Our study was approved by the University Hospitals Human Research Committee (IRB 03-07-10).

References

- Armstrong April W., Harskamp Caitlin T., and Armstrong Ehrin J.. 2013. “The Association between Psoriasis and Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies.” Journal of Hypertension 31 (3): 433–42; discussion 442–443. 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32835bcce1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Lauren Y, Soler David C, Debanne Sarah M, Grozdev Ivan, Rodriguez Myriam E, Feig Rivka L et al. 2013. “Psoriasis and Cardiovascular Risk Factors: Increased Serum Myeloperoxidase and Corresponding Immunocellular Overexpression by Cd11b+ CD68+ Macrophages in Skin Lesions.” American Journal of Translational Research 6 (1): 16–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corraini Priscila, Olsen Morten, Pedersen Lars, Dekkers Olaf M, and Vandenbroucke Jan P. 2017. “Effect Modification, Interaction and Mediation: An Overview of Theoretical Insights for Clinical Investigators.” Clinical Epidemiology 9 (June): 331–38. 10.2147/CLEP.S129728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilek Nursel, Aziz Ramazan Dilek Yakup Taşkın, Taşkın Erkinüresin Ömer Yalçın, and Saral Yunus. 2016. “Contribution of Myeloperoxidase and Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase to Pathogenesis of Psoriasis.” Advances in Dermatology and Allergology/Postȩpy Dermatologii i Alergologii 33 (6): 435–39. 10.5114/ada.2016.63882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gail M, Simon R. 1985. “Testing for Qualitative Interactions between Treatment Effects and Patient Subsets.” Biometrics 41 (2): 361–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh D, Vogt A. 2012. “Outliers: An Evaluation of Methodologies.” Joint Statistical Meetings, 3455–60. [Google Scholar]

- Huang Huiyun, Shen Erdong, Tang Shiqing, Tan Xingyou, Guo Xiuli, Wang Qiang, et al. 2015. “Increased Serum Resistin Levels Correlate with Psoriasis: A Meta-Analysis.” Lipids in Health and Disease 14 (May). 10.1186/s12944-015-0039-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston A, Arnadottir S, Gudjonsson JE, Aphale A, Sigmarsdottir AA, Gunnarsson SI, et al. 2008. “Obesity in Psoriasis: Leptin and Resistin as Mediators of Cutaneous Inflammation.” British Journal of Dermatology 159 (2): 342–50. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08655.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makni Emna, Moalla Wassim, Lamia Benezzeddine-Boussaidi Gérard Lac, Tabka Zouhair, and Elloumi Mohammed. 2013. “Correlation of Resistin with Inflammatory and Cardiometabolic Markers in Obese Adolescents with and without Metabolic Syndrome.” Obesity Facts 6 (4): 393–404. 10.1159/000354574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muse Evan D., Feldman David I., Blaha Michael J., Dardari Zeina, Blumenthal Roger S., Budoff Matthew J., et al. 2015. “The Association of Resistin with Cardiovascular Disease in The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis.” Atherosclerosis 239 (1): 101–8. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.12.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norata GD, Ongari M, Garlaschelli K, Raselli S, Grigore L, and Catapano AL. 2007. “Plasma Resistin Levels Correlate with Determinants of the Metabolic Syndrome.” European Journal of Endocrinology 156 (2): 279–84. 10.1530/eje.1.02338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos Dimitrios P, Makris Thomas K, Krespi Panagiota G, Maria Poulakou, Georgios Stavroulakis, et al. 2007. “Adiponectin and Resistin Plasma Levels in Healthy Individuals With Prehypertension.” The Journal of Clinical Hypertension 7 (12): 729–33. 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2005.04888.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pina T, Genre F, Lopez-Mejias R, Armesto S, Ubilla B, Mijares V, et al. 2015. “Relationship of Leptin with Adiposity and Inflammation and Resistin with Disease Severity in Psoriatic Patients Undergoing Anti-TNF-alpha Therapy.” Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 29 (10): 1995–2001. 10.1111/jdv.13131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi Abrar A., Choi Hyon K., Setty Arathi R., and Curhan Gary C.. 2009. “Psoriasis and the Risk of Diabetes and Hypertension: A Prospective Study of US Female Nurses.” Archives of Dermatology 145 (4): 379–82. 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks FM, Pfeffer MA, Moye LA, Rouleau JL, Rutherford JD, Cole TG, et al. 1996. “The Effect of Pravastatin on Coronary Events after Myocardial Infarction in Patients with Average Cholesterol Levels. Cholesterol and Recurrent Events Trial Investigators.” The New England Journal of Medicine 335 (14): 1001–9. 10.1056/NEJM199610033351401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snekvik Ingrid, Smith Catherine H., Nilsen Tom I. L., Langan Sinéad M., Modalsli Ellen H., Romundstad Pål R., et al. 2017. “Obesity, Waist Circumference, Weight Change, and Risk of Incident Psoriasis: Prospective Data from the HUNT Study.” The Journal of Investigative Dermatology 137 (12): 2484–90. 10.1016/j.jid.2017.07.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Hidetoshi, Tsuji Hitomi, Honma Masaru, Ishida-Yamamoto Akemi, and Iizuka Hajime. 2013. “Increased Plasma Resistin and Decreased Omentin Levels in Japanese Patients with Psoriasis.” Archives of Dermatological Research 305 (2): 113–16. 10.1007/s00403-012-1310-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Rui, Lagakos Stephen W., Ware James H., Hunter David J., and Drazen Jeffrey M.. 2007. “Statistics in Medicine — Reporting of Subgroup Analyses in Clinical Trials.” New England Journal of Medicine 357 (21): 2189–94. 10.1056/NEJMsr077003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Yuxiang, Li Yixing, Yu Lin, and Zhou Lei. 2017. “Association between Serum Resistin Concentration and Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Oncotarget 8 (25): 41529–37. 10.18632/oncotarget.17561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.