Abstract

Hypertension is the most common risk factor for cardiovascular disease, causing over 18 million deaths a year. Although the mechanisms controlling blood pressure (BP) in either sex remain largely unknown, T cells play a critical role in the development of hypertension. Further evidence supports a role for the immune system in contributing to sex differences in hypertension. The goal of the current study was to first, determine the impact of sex on the renal T cell profiles in DOCA-salt hypertensive males and females, and secondly, test the hypothesis that greater numbers of T regulatory cells (Tregs) in females protect against DOCA-salt induced increases in BP and kidney injury. Male rats displayed greater increases in BP than females following 3 weeks of DOCA-salt treatment, although increases in renal injury were comparable between the sexes. DOCA-salt treatment resulted in an increase in pro-inflammatory T cells in both sexes, however, females had more anti-inflammatory Tregs than males. Additional male and female DOCA-salt rats were treated with anti-CD25 to decrease Tregs. Decreasing Tregs significantly increased BP only in females, thereby abolishing the sex difference in the BP response to DOCA-salt. This data supports the hypothesis that Tregs protect against the development of hypertension and are particularly important for the control of BP in females.

Keywords: Hypertension, Sex, Gender, Tregs, Kidney, Inflammation

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Hypertension is the most common risk factor for cardiovascular disease, which is the leading cause of death among both men and women, causing over 18 million deaths a year worldwide1. Although the mechanisms controlling blood pressure (BP) in either sex remain largely unknown, there is an ever-expanding literature base implicating a role for chronic inflammation in the development of hypertension2–4. More specifically, T cells have been shown to be critical in the development of hypertension using multiple experimental models5. T cells have also been suggested to contribute to sex differences in BP control6, 7, yet little is known regarding the relative role of different T cell subtypes in BP control in males vs. females.

The DOCA-salt model of hypertension incorporates the activation of mineralocorticoid receptors and a high salt intake, both of which have been shown to play key roles in the development of hypertension as well as inflammation8, 9. Indeed, treatment of male DOCA-salt rats with the lymphocyte inhibitor, mycophenolate mofetil, attenuates DOCA-salt induced increases in BP10, and male Rag1−/− mice lacking B and T cells have a blunted increase in BP to DOCA-salt treatment vs. wildtype control mice5. These data support a central role for T cells in the development of hypertension in DOCA-salt hypertension in males. However, not all T cell subtypes are pro-hypertensive2, 11. T regulatory cells (Tregs) are an anti-inflammatory, anti-hypertensive subset of T cells that suppress immune effector function and attenuate increases in BP12–15. Interestingly, male DOCA-salt rats have previously been shown to exhibit a decrease in circulating and renal anti-inflammatory Tregs16, and this may further contribute to increases in BP.

Our lab has previously reported that there are sex differences in the renal T cell profile in both spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) and angiotensin II-induced hypertensive rats; where females have more Tregs than males3, 17. Moreover, female SHR exhibit a BP-dependent upregulation of Tregs that corresponds to a lower BP when compared to males18, suggesting that Tregs are particularly important in BP control in females. However, there is a lack of information in the literature regarding the impact of DOCA-salt on T cells in females. The goal of the current study was to determine the impact of sex on renal T cell profiles in DOCA-salt hypertensive males and females. Therefore, initial experiments in the current study measured the renal T cell profile using flow cytometric analysis in male and female DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Consistent with previous studies, female DOCA-salt rats have more renal Tregs than males. Additional experiments further tested the hypothesis that greater numbers of Tregs in females protect against DOCA-salt induced increases in BP and kidney injury to a greater extent than in male rats.

Materials and Methods

The authors declare that all supporting data are available within the article and its online-only Data Supplement.

Animals

Nine to ten-week-old male and female Sprague Dawley (SD) rats were purchased from Envigo, Inc. (Indianapolis, IN) between November 2017 and December 2018. All animal procedures were approved by the Augusta University Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and were conducted in compliance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Rats were housed in humidity and temperature controlled, light-cycled quarters, and maintained on standard chow (Teklad Global 18% Protein Rodent Diet 2918; cat # 2918–091619M). At 10 weeks of age, all rats were anesthetized and a uni-nephrectomy (UNX) was performed. After one week of recovery, DOCA-salt rats received a subcutaneous 21-day slow-release deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA) pellet (200 mg) with saline (0.9%) to drink. UNX control rats received tap water to drink (n=11–12). A subset of DOCA-salt rats were implanted with telemetry devices (Data Sciences International, St Paul, MN; cat # 270-0180-001) at the same time as the UNX for the measurement of mean arterial pressure (MAP) for 3 weeks.

Additional male and female DOCA and UNX rats were euthanized after one week of DOCA-salt (n=12) for tissue collection prior to the development of a sex difference in BP. At the end of all studies, rats were anesthetized with isoflurane, a thoracotomy was performed, and a terminal blood sample was obtained. The remaining kidney was isolated and processed for flow cytometric analysis of T cells as previously described17, 18, immunohistochemical analysis of macrophage infiltration19, and histological analysis of renal structure and injury. Additional details and gating strategy are provided in the Online Supplement.

Anti-CD25 Treatment

Additional male and female DOCA rats (n=5–8) were randomized to receive weekly intraperitoneal (ip) injections of anti-CD25 antibody for 3 weeks (1 mg/ml; eBioscience cat # 16-0390-85) or anti-IgG (control). The anti-CD25 antibody targets the CD25 surface marker on Tregs to decrease circulating Tregs20–22. Pilot studies determined the dose of anti-CD25 to decrease Tregs in male and female SD rats (Online Supplement). Based on pilot studies, rats were injected with 250 μg of anti-CD25 every seven days for 3 weeks to decrease Tregs.

Assessment of Renal Injury

A Kim1/Tim1 ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, cat # RKM100) was run on plasma samples to quantify kidney injury molecule-1/T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-1. To score glomerular injury, kidney sections were paraffin embedded and cut into 5 μm sections for staining with Masson’s trichrome to assess collagen deposition. An expert in clinical pathology blindly scored all slides at 200x magnification on a graded scale (0.5: least collagen/injury to 5.0: maximal collagen/injury). A Sirius Red/Fast Green collagen staining kit (Chondrex, Inc., Redmond, WA cat # 9046) was also used to quantify fibrosis (μm collagen per sample) on 15 μm mounted kidney sections.

Statistical Analysis

Telemetry data were analyzed using repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). Flow cytometry data, renal injury scores, and macrophage infiltration counts were compared using a two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism Version 7.01 software (GraphPad Software Inc, La Jolla, CA) and for all comparisons differences were considered statistically significant with p<0.05. All data presented as mean ± SEM.

Results

Males have greater increases in BP with DOCA-salt vs. females; renal injury is comparable between the sexes.

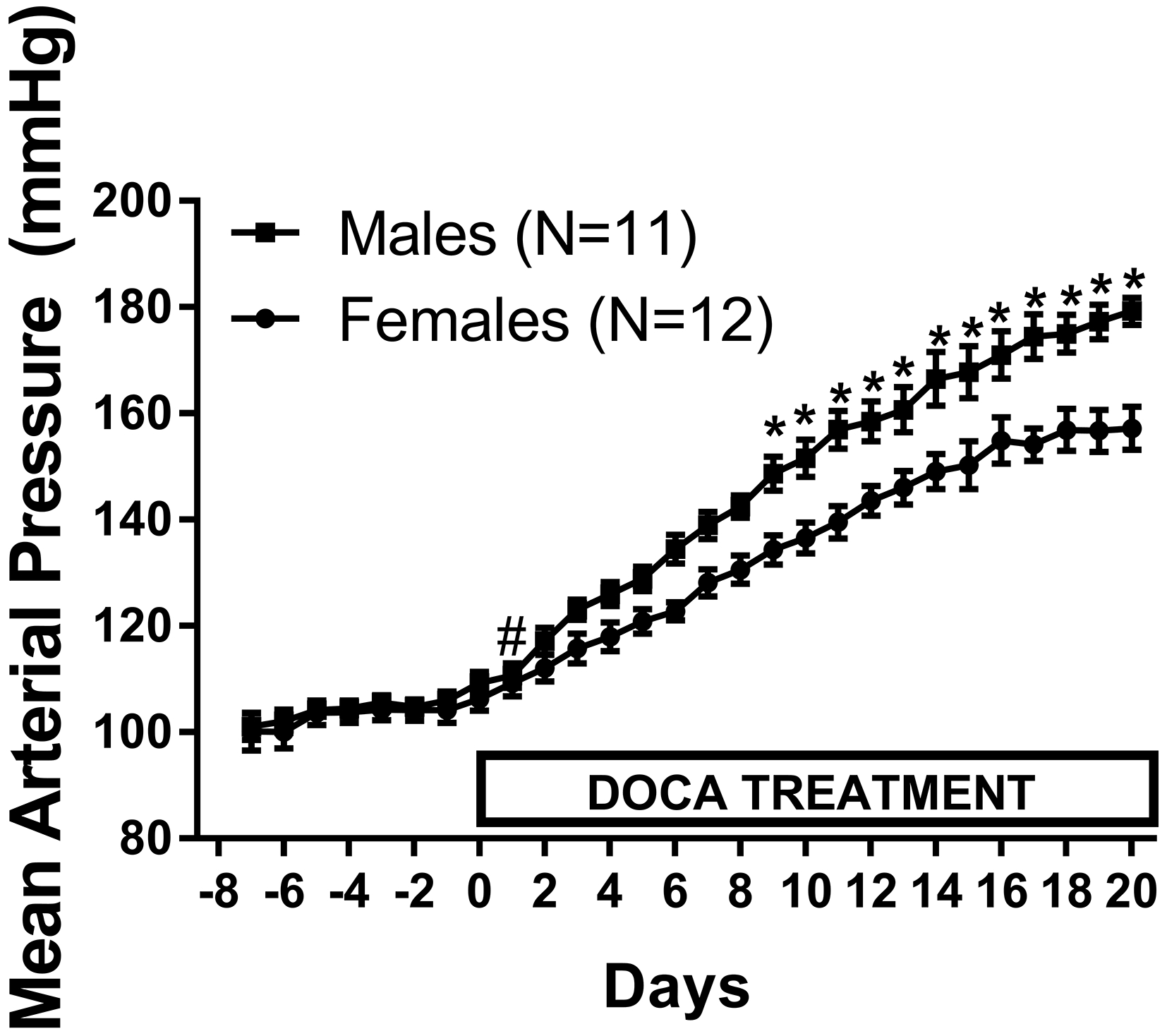

BP was measured in male and female rats during 21 days of DOCA-salt treatment. DOCA-salt significantly increased BP in both males (p=0.03) and females (p=0.05) by day 2 of treatment. At the end of 21-days of treatment, BP was significantly higher in males vs. females (Fig 1; mmHg: males 179 ± 3; n=6; females 157 ± 4; n=7; P<0.0001). The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated to assess the overall pressure load induced by DOCA-salt in both sexes after 1 and 3 weeks of treatment. The overall increase in pressure load following week one of DOCA-salt treatment was comparable between males and females (AUC: males: 1486±23; females: 1454±34; p=0.47). However, males display a greater pressure load after 3 weeks of treatment compared to females (AUC: males: 3610±57; females 3349±67; p=0.009).

Figure 1:

24 hour mean arterial pressure (MAP) was measured via telemetry in male (M) and female (F) Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (n=11–12). After 1 week of baseline MAP measurements, rats were treated with DOCA-salt for 21 days. Data within each sex were analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test and between group comparisons were made using a t-test. # indicates p<0.05 vs. baseline MAP; * indicates p<0.05 vs. male.

Additional studies measured renal injury in males and females after 1 and 3 weeks of DOCA-salt treatment; before (1 week) and after (3 week) the development of a sex difference in BP. Despite significant increases in BP in both males and females with 1 week of DOCA-salt treatment, neither Kim1/Tim1 (Table 1; n=6; effect of treatment: p=0.18), fibrosis (Table 1; n=5–6; effect of treatment: p=0.25), or glomerular injury (Table 1 and Fig S4A; n=6; effect of treatment: p=0.45) were increased in either sex. Moreover, Kim1/Tim1 (effect of sex: p=0.57; interaction: p=0.11), fibrosis (effect of sex: p=0.75; interaction: p=0.25), and glomerular injury (effect of sex: p>0.99; interaction: p>0.99) were comparable between males and females. In contrast, 3 weeks of DOCA-salt treatment resulted in pronounced injury in both sexes with increases in Kim1/Tim1 (Table 1; n=4–6; effect of treatment: P=0.03), fibrosis (Table 1; n=4–6; effect of treatment: P=0.0001), glomerular injury (Table 1 and Fig S4B; n=6; effect of treatment: P<0.0001). Despite males having a greater overall increase in BP with 3 weeks of DOCA-salt treatment, Kim1/Tim1 (effect of sex: p=0.74; interaction: p=0.89), fibrosis (effect of sex: p= 0.38; interaction: p=0.45), and glomerular injury (effect of sex: p=0.19; interaction: p=0.39) were comparable between males and females.

Table 1:

Kidney injury markers and scores in male and female rats following 1 or 3 weeks of UNX control and DOCA salt treatment.

| 1 Week | Male UNX | 398 ± 19 | 0.016 ± 0.001 | 0.75 ± 0.11 |

| Male DOCA | 339 ± 11 | 0.016 ± 0.001 | 0.83± 0.11 | |

| Female UNX | 355 ± 22 | 0.017 ± 0.001 | 0.75 ± 0.11 | |

| Female DOCA | 360 ± 23 | 0.015 ± 0.001 | 0.83 ± 0.11 | |

| Interaction | p=0.11 | p=0.25 | p>0.99 | |

| Effect of Treatment | p=0.18 | p=0.25 | p=0.45 | |

| Effect of Sex | p=0.57 | p=0.75 | p>0.99 | |

| 3 Week | Male UNX | 338 ± 18 | 0.016 ± 0.001 | 1.33 ± 0.17 |

| Male DOCA | 636 ±95 | 0.021 ± 0.001 | 2.58 ± 0.24 | |

| Female UNX | 293 ± 25 | 0.018 ± 0.001 | 1.25 ± 0.11 | |

| Female DOCA | 606 ± 88 | 0.022 ± 0.001 | 2.17 ± 0.21 | |

| Interaction | p=0.89 | p=0.45 | p=0.39 | |

| Effect of Treatment | p=0.03* | p=0.001* | p<0.0001* | |

| Effect of Sex | p=0.74 | p=0.38 | p=0.19 |

Renal injury was measured following 1 or 3-weeks of UNX or DOCA-salt treatment in male and female SD rats (n=5–6) via plasma Kim1/Tim 1 (ELISA), Sirius Red/Fast Green collagen staining (fibrosis), and glomerular injury (trichrome staining). Analysis of glomerular injury was performed in a blinded manner. All data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA;

indicates a significant difference.

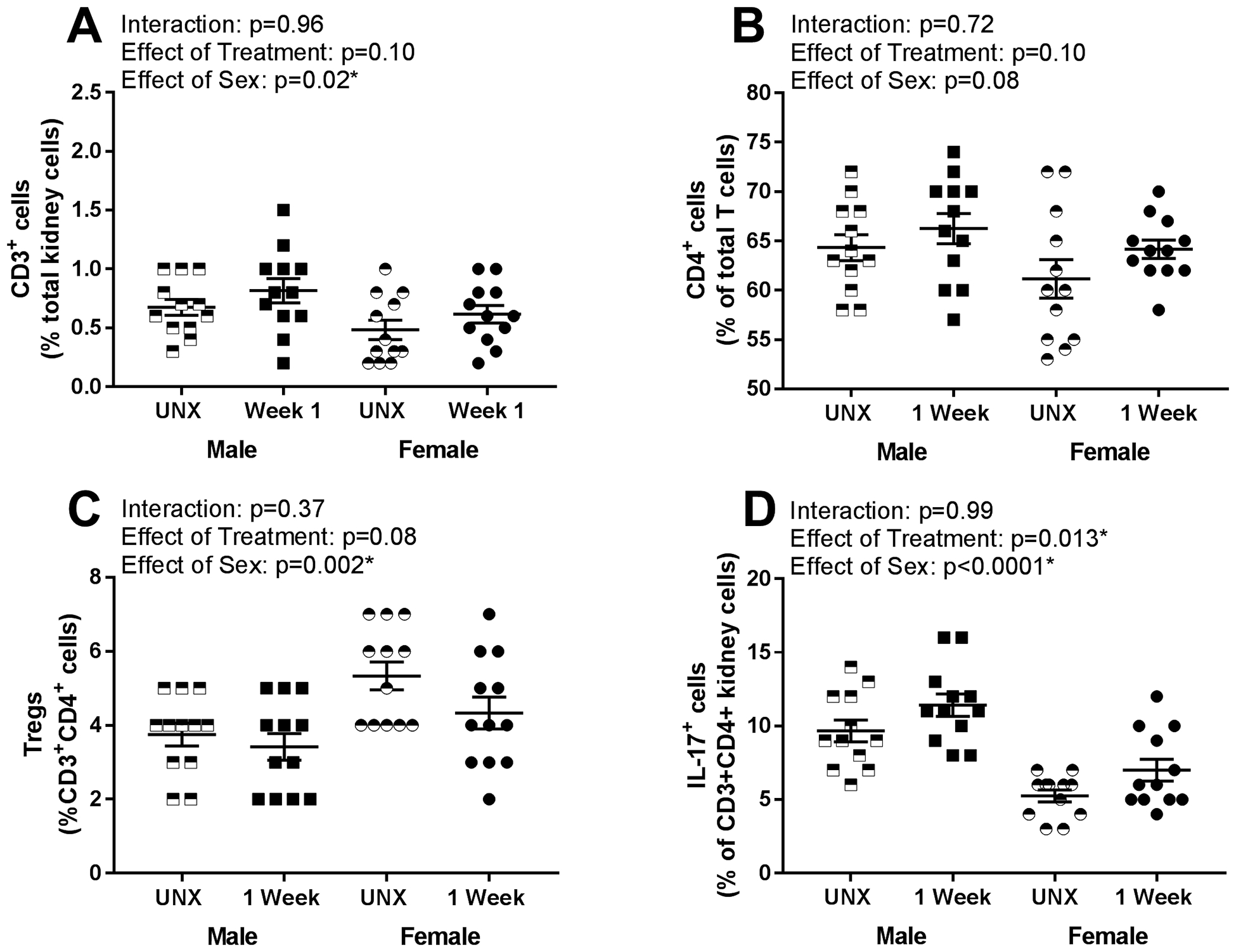

3 weeks of DOCA-salt leads to a more pro-inflammatory profile in males.

T cells contribute to DOCA-salt-induced renal injury in males5, therefore additional studies measured the renal T cell profile after 1 and 3 weeks of UNX and DOCA-salt treatment in both sexes; before (1 week) and after (3 week) the development of renal injury. One week of DOCA-salt did not alter the numbers of renal CD3+ T cells (Fig 2A; n=12; effect of treatment: p=0.1), CD4+ T cells (Fig 2B; n=12; effect of treatment: p=0.1) or Tregs (Fig 2C; n=12; effect of treatment: p=0.08) in either sex. However, Th17 cells were increased with DOCA-salt treatment (Fig 2D; n=12; effect of treatment 0.013). Males had more CD3+ T cells (effect of sex: p=0.02; interaction: p=0.96) and Th17 cells (effect of sex: p<0.0001; interaction: p=0.99), while females had more Tregs (effect of sex: p=0.002; interaction: p=0.37). CD4+ T cells were comparable between the sexes (effect of sex: p=0.08; interaction: p=0.72).

Figure 2:

Renal T cell profiles were measured via flow cytometric analysis in male and female rats following 1 week of UNX control or DOCA-salt treatment (n=12). Shown are percentages of (A) total CD3+ T cells expressed as a percentage of total renal cells: Pinteraction = 0.96; Ptreatment = 0.10; Psex = 0.02, (B) CD4+ T cells expressed as a percentage of total CD3+ T cells: Pinteraction = 0.72; Ptreatment = 0.10; Psex = 0.08, (C) Foxp3+ T regulatory cells (Tregs) expressed as a percentage of CD3+CD4+ T cells: Pinteraction = 0.37; Ptreatment = 0.08; Psex = 0.002, and (D) IL-17+ T helper (Th)17 cells expressed as a percentage of CD3+CD4+ T cells: Pinteraction = 0.99; Ptreatment = 0.013; Psex < 0.0001. Data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA.

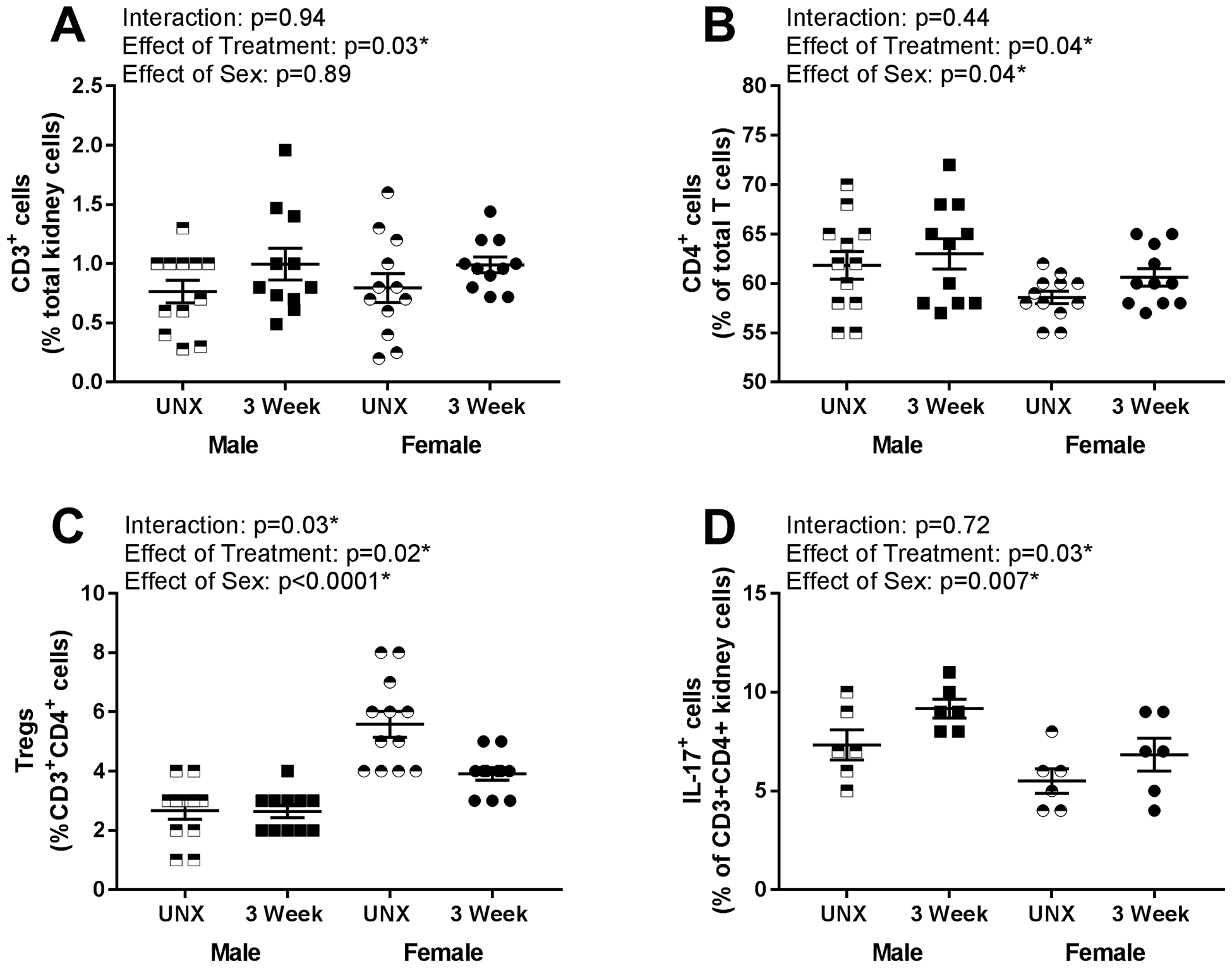

Three weeks of DOCA-salt treatment resulted in significant increases in renal CD3+ T cells (Fig 3A; n=11–12; effect of treatment: p=0.03), CD4+ T cells (Fig 3B; n=11–12; effect of treatment: p=0.04), and Th17 cells (Fig 3D; n=6; effect of treatment: p=0.03). Increases in CD3+ T cells (interaction: p=0.94), CD4+ T cells (interaction: p=0.44), and Th17 cells (interaction: p=0.72) were comparable between sexes. However, males had more CD4+ T cells (effect of sex: p=0.04) and Th17 cells (effect of sex: p=0.007); there was no sex difference in CD3+ cells (effect of sex: p=0.89). 3 weeks of DOCA-salt decreased Tregs in both sexes (Fig 3C; n=11–12; effect of treatment: p=0.008), although females maintained higher numbers of Tregs than males (effect of sex: p<0.0001; interaction: p=0.03).

Figure 3:

Renal T cell profile measured via flow cytometric analysis in male and female rats following 3 weeks of UNX control or DOCA-salt treatment (n=12). Shown are percentages of (A) total CD3+ T cells expressed as a percentage of total renal cells: Pinteraction = 0.94; Ptreatment = 0.03; Psex = 0.89, (B) CD4+ T cells expressed as a percentage of total CD3+ T cells: Pinteraction = 0.44; Ptreatment = 0.04; Psex = 0.04, (C) Foxp3+ T regulatory cells (Tregs) expressed as a percentage of CD3+CD4+ T cells: Pinteraction = 0.03; Ptreatment = 0.02; Psex < 0.0001, (D) IL-17+ T helper (Th)17 cells expressed as a percentage of CD3+CD4+ T cells: Pinteraction = 0.72; Ptreatment = 0.03; Psex = 0.007. Data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA.

Additional studies measured renal macrophage infiltration by immunohistochemical analysis. There was a significant increase in renal macrophages after 1 week of DOCA treatment (Fig S5B: effect of treatment: p<0.0001) and macrophages remained elevated when compared to UNX controls after 3 weeks of treatment (Fig S5D; effect of treatment: p<0.0001). There was no sex difference in macrophage infiltration after either 1 (effect of sex: p=0.46; interaction: p=0.58) or 3 weeks of DOCA-salt treatment (effect of sex: p=0.68; interaction: p=0.90).

Tregs limit DOCA-salt-induced increases in BP in females.

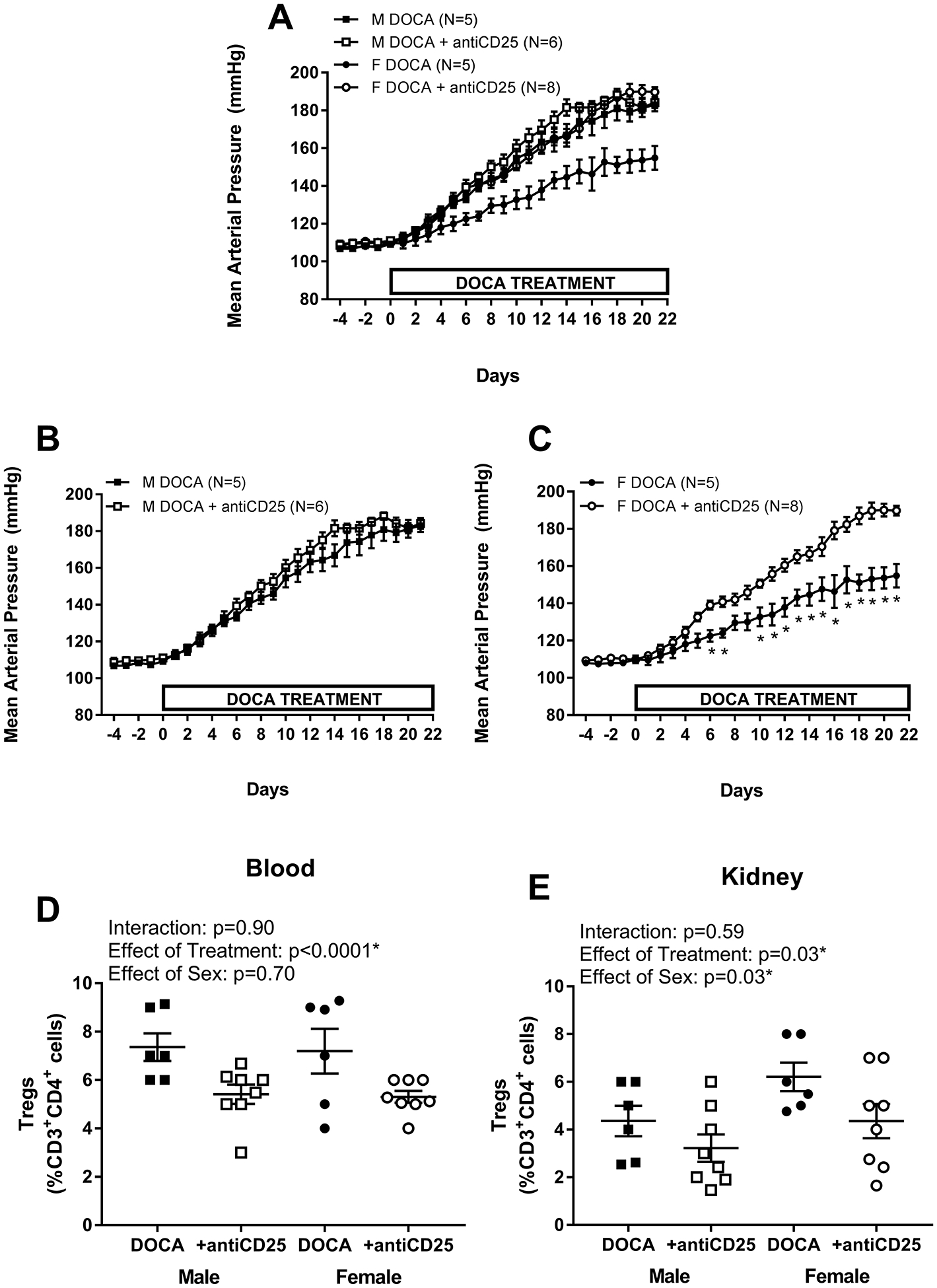

Additional studies used anti-CD25 to decrease Tregs to determine if Tregs protect against DOCA-salt-induced increases in BP or renal injury. Treatment with anti-CD25 significantly decreased circulating (Fig 4A; males: 26% decrease, females: 26% decrease; effect of treatment: p<0.0001) and renal Tregs (Fig 4B; males: 26% decrease, females: 29% decrease; effect of treatment: p=0.03); decreases were comparable between the sexes (interaction blood: p=0.9; interaction kidney: p=0.59). Consistent with the data above, females had more renal Tregs than males (effect of sex: p=0.03), however, there was no sex difference in circulating Tregs (effect of sex: p=0.70).

Figure 4:

24 hour mean arterial pressure (MAP) was measured via telemetry in male (M; A and B) and female (F; A and C) Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (n=6–8). After 4 days of baseline MAP measurements, rats were treated with DOCA-salt plus weekly control IgG or anti-CD25 injections and MAP was measured for 21 days. At the end of the treatment, blood (D) and the remaining kidney (E) were isolated to measure Tregs by flow cytometric analysis. MAP data within each sex were analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test and between group comparisons were made using a t-test. * indicates p<0.05 vs. DOCA controls. Flow cytometric data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA.

Treatment with anti-CD25 did not alter DOCA-salt-induced increases in BP in males (Fig 4C; n=5–6; final BP mmHg: 183 ± 3 vs. 184 ± 3; p>0.999). However, decreasing Tregs significantly increased BP sensitivity to DOCA-salt in females (Fig 4D; n=5–8; final BP mmHg: 156 ± 6 vs. 190 ± 3; p<0.000). Anti-CD25 increased the DOCA-salt pressure load over 3 weeks of treatment in females (AUC: 3242±97 vs. 3620±52; p=0.003) with no change in males (AUC: 3602.66±66 vs. 3734±53; p=0.15), thereby abolishing the sex difference in BP with DOCA (Fig 4E).

To determine if DOCA-salt induced renal injury was also modulated by Tregs, Kim1/Tim1, fibrosis, and glomerular injury were measured in control DOCA and anti-CD25-treated DOCA-sat rats. Anti-CD25 did not alter Kim1/Tim1 levels (Table 2; n=6; effect of treatment: p=0.32), fibrosis (Table 2; n=6; effect of treatment: p=0.36), or glomerular injury (Table 2 and Fig S10; n=6; effect of treatment: p=0.21) in either sex. Moreover, Kim1/Tim1 (effect of sex: p=0.63; interaction: p=0.77) and glomerular injury (effect of sex: p=0.67; interaction: p=0.39) were comparable between males and females. However, females had more fibrosis than males (effect of sex: p=0.04; interaction: p=0.83).

Table 2:

Kidney injury markers and scores in male and female rats following 3 weeks of DOCA salt treatment in the absence or presence of antiCD25 to decrease Tregs.

| Male DOCA | 542 ± 96 | 0.016 ± 0.0019 | 2.3 ± 0.21 |

| Male DOCA + antiCD25 | 663 ± 77 | 0.14 ± 0.0006 | 2.3 ± 0.17 |

| Female DOCA | 523 ± 84 | 0.018 ± 0.0017 | 2.0 ± 0.13 |

| Female DOCA + antiCD25 | 590 ± 100 | 0.17 ± 0.001 | 2.4 ± 0.24 |

| Interaction | p=0.77 | p=0.83 | p=0.39 |

| Effect of Treatment | p=0.32 | p=0.36 | p=0.21 |

| Effect of Sex | p=0.63 | p=0.04* | p=0.67 |

Renal injury was measured in male and female SD rats following 3 weeks of DOCA control or DOCA+anti-CD25 (n=5–8) via plasma Kim1/Tim 1 (ELISA), Sirius Red/Fast Green collagen staining (fibrosis), and glomerular injury (trichrome staining). Analysis of glomerular injury was performed in a blinded manner. All data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA;

indicates a significant difference.

Discussion

It is well established that the immune system plays a critical role in the development of hypertension3, 4, 23, and evidence further supports a role for the immune system in contributing to sex differences in hypertension6, 7. In both clinical and experimental models of hypertension, females tend to have lower BPs compared to males and the lower BP in females is typically associated with a more anti-inflammatory T cell profile1, 17. The primary finding of the current study is that Tregs preferentially protect female rats from DOCA-salt-induced increases in BP. Consistent with other models of hypertension, female DOCA-salt rats have more renal Tregs than males17, 24. Subsequently, treatment with anti-CD25 to lower Tregs increased BP in females only and abolished the sex difference in BP to DOCA-salt. These results provide additional insight regarding the mechanisms controlling hypertension, especially in females, and support the hypothesis that Tregs are particularly important for the control of BP in females and protect against the development of hypertension.

Consistent with previous studies, males are more sensitive to DOCA-salt induced increases in BP than females25–33. The majority of studies that have examined the impact of sex on DOCA-salt hypertension have focused on vascular responses29, 30, 32. However, based on the central role for the kidney in the long-term control of BP, this study examined DOCA-salt-induced increases in both BP and renal injury in males vs. females. Increased BP following DOCA-salt in males leads to renal injury34, 35. Consistent with previous studies in male DOCA-salt rats35, increases in BP precede increases in injury in both sexes, indicating that BP, and not DOCA-salt treatment alone, drives renal injury. Since lower BP in females is associated with lower indices of renal injury in other experimental models of hypertension17, 24, 36, we anticipated that females would have less injury with DOCA-salt than males. Although little is known regarding the impact of DOCA-salt-induced increases in BP on kidney injury in males vs. females, following 5 weeks of DOCA-salt treatment female Wistar rats have a lower BP (systolic BP: 170 mmHg in females vs. 189 mmHg in males) and less renal injury when assessed by histological analysis of PAS-stained kidney slices33. In contrast, injury was comparable following 3 weeks of DOCA-salt treatment in male and female SD rats in the current study. This discrepancy may reflect differences in the DOCA preparation and delivery, duration of treatment, or strain of rats used in the individual studies. Our findings may also suggest enhanced sensitivity of females to DOCA-salt-induced renal injury when measured via multiple methods. Alternatively, terminal BP values in both sexes are relatively high at the end of our study compared to the study above when BP was measured by tail-cuff33. As a result, renal injury may be maximized in both sexes, thereby obscuring any potential sex difference. Indeed, as discussed below, further increases in BP with anti-CD25 did not result in greater increases in renal injury in female rats. Additional studies are needed to more fully address this question.

Regardless, our study provides novel insight into renal disease progression between the sexes. There are reports of sex differences in basal expression of genes used to assess renal injury37, 38, yet there remains a lack of experimental data in females to support this. When assessing global gene expression in the kidney of male and female F344 rats from 2 to 104 weeks of age, filtering the data for differential expression by sex resulted in 841 genes displaying a sex difference at one or more age. These genes included Kim-1, which displayed a 23-fold difference with a female-bias at 8 weeks of age, causing the authors to call into question the utility of this as a marker for injury between the sexes as fibrosis was greater in males with age. However, in the current study we provide evidence that not only is there not a sex difference in the levels of Kim/Tim1, but changes in Kim/Tim 1 correlate with changes in fibrosis in both sexes; the correlation coefficient in both sexes was 1.0.

Inflammation has been implicated in DOCA-salt induced increases in BP and renal injury10, 34, 35 in males, and male mice lacking T cells have an attenuated increase in BP with DOCA-salt5. Sex differences in Ang II-hypertension are also mediated in part by T cells5, therefore, additional studies examined the impact of DOCA-salt on renal T cells after 1 week (when BP was increased but there was no sex difference) and after 3 weeks (further increases in BP and the development of a sex difference) in male and female rats. Consistent with previous reports39, increases in BP largely preceded DOCA-salt-induced increases in inflammation in the current study. These data support the hypothesis that increases in BP are required to initiate an inflammatory response and that T cells then act to further amplify increases in BP. By 3 weeks, there were significant increases in pro-inflammatory T cells in both sexes. Consistent with findings in SHR and Ang II models of hypertension17, 24, male DOCA-salt rats had a higher BP and more pro-inflammatory T cells than females.

Of interest, there was a significant increase in macrophage infiltration following 1 week of DOCA-salt treatment and macrophages remained elevated at 3 weeks. This is consistent with previous reports of increased monocyte and macrophage infiltration in hypertensive kidneys of males40. Previous studies have shown that females have lower macrophage infiltration than males in both SHR19 and Dahl salt sensitive models of hypertension41. However, no sex differences were found in the current study. The role of macrophages in mediating T cell infiltration and the progression of hypertension and T cell infiltration will be examined in future studies.

An imbalance in the Th17/Treg ratio has been suggested to contribute to the development of hypertension16, 42. Although there were no significant increases in renal CD3+ or CD4+ T cells following 1 week of DOCA-salt treatment, Th17 cells were increased. Consistent with our result, RORγt and IL-17 mRNA expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, spleen and kidney are increased in male DOCA-salt rats within 8 days of DOCA treatment16. In contrast, Tregs are anti-inflammatory T cells that suppress Th17 activation43, and increases in Tregs are associated with decreases in BP and hypertensive end-organ damage in both sexes13, 44, 45. Interestingly, in contrast with the above study16 which reported an increase in FoxP3 (the transcription factor that drives the differentiation of Tregs) mRNA in blood, heart and kidney with DOCA-salt in males, we found a trend for Tregs to decrease in females with 1 week of DOCA-salt (p=0.08) which again reached significance by 3 weeks when measured by flow cytometry. However, consistent with the above report, FoxP3 mRNA expression increased in the aorta following 3 weeks of DOCA-salt treatment in both sexes (effect of treatment: p=0.02; Figure S6). Regardless, since renal Th17 cells increased and Tregs decreased with DOCA-salt treatment in the current study, the Th17:Treg ratio in the kidney was largely unaffected by DOCA-salt treatment in either sex. However, males had a higher Th17:Treg ratio than females indicating a more pro-inflammatory renal T cell profile.

To determine if the sex difference in renal Tregs simply reflected a sex difference in Treg production, splenic Tregs were measured by flow cytometric analysis and RT-PCR. Splenic Tregs were comparable among all 4 groups, suggesting neither DOCA-salt treatment or sex impacted Treg production. We further measured FoxP3 mRNA in the aorta as an index of Treg infiltration to assess if the sex difference in Tregs was unique to the kidney. As indicated above, both the literature16 and the current study report an increase in aortic FoxP3 mRNA expression and previous studies have shown that Tregs are protective in the aorta and heart of hypertensive mice12, 46. In contrast to our findings in the kidney however, there were no sex differences in aortic FoxP3 mRNA expression. Future studies will be designed to determine the mechanisms that regulate renal targeting and recruitment of Tregs in males vs. females.

Numerous studies have established that the adoptive transfer of Tregs attenuates the development of experimental models of hypertension in males5, 12, 46, supporting an anti-hypertensive role for exogenous Tregs. In the current study, females maintained more Tregs than males following 3 weeks of DOCA-salt treatment and females have a lower BP than males. Moreover, decreasing Tregs resulted in increased BP sensitivity to DOCA-salt only in females, abolishing the sex difference in DOCA-salt hypertension. These data support the hypothesis that females are highly dependent on Tregs to maintain their BP, and Tregs contribute to sex differences in BP control. Indeed, previous work by our laboratory has shown that female SHR have more renal Tregs than males17, and females have a compensatory increase in renal Tregs with increases in BP which we propose contributes to the lower BP in young adult female SHR compared to males18. Ang II infusion for 2 weeks also results in greater increases in Tregs in female rats compared to males36, and a recent study showed that Tregs protect against Ang II-induced hypertension in premenopausal female mice14.

The finding that decreasing Tregs in males did not alter BP may reflect the finding that males have fewer Tregs in comparison to females and as a result may not be as dependent on Tregs to maintain BP under normal, physiological conditions. In addition, a limitation of the current study is that we did not assess Treg function. If DOCA-salt impairs Treg function, male would again be more sensitive to this as they have fewer Tregs. We would predict based on Treg adoptive transfer studies5, 12, 46 that opposed to decreasing endogenous Tregs, but instead increasing Tregs via adoptive transfer would lower BP with DOCA-salt. Similarly, although numerous studies have demonstrated a key role of adaptive immunity in hypertensive end organ damage47, 48, much less is known regarding the in vivo manipulation of endogenous Tregs on hypertensive renal injury. Surprisingly, decreasing Tregs had no impact on renal injury in either sex, suggesting that Tregs, although important for the development and control of hypertension in females, have no influence on hypertensive renal injury in either sex. However, as stated above, renal injury may have already been maximized preventing the detection of any further increase with the loss of endogenous Tregs. A more effective approach to modulate renal injury may be to increase Tregs via adoptive transfer from a normotensive control as has been shown in male mice49. Future studies will test this hypothesis.

There are some limitations and caveats associated with the current study. Flow cytometry data are presented as percentages based on reading 20,000 events; total cell number was not measured. However, the same individual, blinded to the groups and hypothesis, using the same gating strategies across all experiments, analyzed all the data. If anything, presenting the data as percentages of total cells underestimates the effect of sex and treatment as DOCA results in renal hypertrophy and males have larger kidneys that females (Table S1). As noted above, another limitation is that the activity of T cells was not measured. However, the finding that decreasing Tregs significantly decreased BP in females suggests that Tregs retain their activity. In addition, we previously reported that female DOCA-salt rats have higher levels of circulating IL-10, which would be consistent with greater Treg activity27. Lastly, there is some controversy regarding the best models to assess the role of immune cells in hypertension. While the early studies were focused on the Rag1−/− mouse5, a recent paper reported that the Rag1−/− mouse is no longer resistant to angiotensin II-induced hypertension due to an increased expression of renal angiotensin type 1-receptor activity that masks the BP protection afforded by the lack of T cells50. Based on our data supporting a role for T cells in both the development of DOCA-salt hypertension and sex differences in the BP response, the DOCA-salt rat model is an excellent model to study the role of T cells in hypertension and hypertensive injury.

Perspectives

The need for novel hypertension therapeutics is lacking due to the limited knowledge on the molecular pathway controlling BP in both males and females. The current study has identified Tregs as a novel mechanism that protects females against DOCA-salt-induced increases in BP. Preclinical studies on Treg therapy have shown a promising capacity of Tregs to prevent graft rejection51 and treat autoimmune diseases, such as Crohn’s disease52 and type 1 diabetes mellitus53. Based on our current results, Treg therapy could also be a promising target for the treatment of hypertension, especially for females.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance:

- What Is New?

- Female DOCA-salt rats have more renal Tregs than male DOCA-salt rats.

- Tregs protect female rats from DOCA-salt-induced increases in BP and contribute to sex differences in BP.

- What Is Relevant?

- Both males and females develop hypertension, yet the majority of basic science studies remain focused on males.

- The inclusion of both males and females allows for the identification of sex-specific mechanisms that contribute to BP control and the development of hypertension with the potential to develop more individualized treatment strategies for both sexes.

-

Summary

Female DOCA-salt rats have more renal Tregs than males and treatment with anti-CD25 to lower Tregs resulted in an increase in BP only in females and abolished the sex difference in BP to DOCA-salt, indicating that Tregs preferentially protect female rats from DOCA-salt-induced increases in BP.

Acknowledgments

Source(s) of Funding: The work was funded by the National Institute of Health (R01HL127091 and P01HL134604 to J.C.S.) and the American Heart Association (17EIA33410565 to J.C.S).

Footnotes

Conflict(s) of Interest/Disclosure(s)

None

References

- 1.American Heart Association. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2019 update. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caillon A, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. Role of immune cells in hypertension. Br J Pharmacol. 2019;176:1818–1828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crislip GR, Sullivan JC. T-cell involvement in sex differences in blood pressure control. Clin Sci (Lond). 2016;130:773–783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schiffrin EL. T lymphocytes: A role in hypertension? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2010;19:181–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guzik TJ, Hoch NE, Brown KA, McCann LA, Rahman A, Dikalov S, Goronzy J, Weyand C, Harrison DG. Role of the t cell in the genesis of angiotensin ii induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2449–2460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pollow DP, Uhrlaub J, Romero-Aleshire M, Sandberg K, Nikolich-Zugich J, Brooks HL, Hay M. Sex differences in t-lymphocyte tissue infiltration and development of angiotensin ii hypertension. Hypertension. 2014;64:384–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ji H, Zheng W, Li X, Liu J, Wu X, Zhang MA, Umans JG, Hay M, Speth RC, Dunn SE, Sandberg K. Sex-specific t-cell regulation of angiotensin ii-dependent hypertension. Hypertension. 2014;64:573–582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klanke B, Cordasic N, Hartner A, Schmieder RE, Veelken R, Hilgers KF. Blood pressure versus direct mineralocorticoid effects on kidney inflammation and fibrosis in doca-salt hypertension. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:3456–3463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young MJ, Rickard AJ. Mechanisms of mineralocorticoid salt-induced hypertension and cardiac fibrosis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;350:248–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moes AD, Severs D, Verdonk K, van der Lubbe N, Zietse R, Danser AHJ, Hoorn EJ. Mycophenolate mofetil attenuates doca-salt hypertension: Effects on vascular tone. Front Physiol. 2018;9:578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sullivan JC, Gillis EE. Sex and gender differences in hypertensive kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2017;313:F1009–F1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barhoumi T, Kasal DA, Li MW, Shbat L, Laurant P, Neves MF, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. T regulatory lymphocytes prevent angiotensin ii-induced hypertension and vascular injury. Hypertension. 2011;57:469–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harmon A, Cornelius D, Amaral L, Paige A, Herse F, Ibrahim T, Wallukat G, Faulkner J, Moseley J, Dechend R, LaMarca B. Il-10 supplementation increases tregs and decreases hypertension in the rupp rat model of preeclampsia. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2015;34:291–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pollow DP Jr., Uhlorn JA, Sylvester MA, Romero-Aleshire MJ, Uhrlaub JL, Lindsey ML, Nikolich-Zugich J, Brooks HL. Menopause and foxp3(+) treg cell depletion eliminate female protection against t cell-mediated angiotensin ii hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2019;317:H415–H423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao H, Liao X, Kang Y. Tregs: Where we are and what comes next? Front Immunol. 2017;8:1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amador CA, Barrientos V, Pena J, Herrada AA, Gonzalez M, Valdes S, Carrasco L, Alzamora R, Figueroa F, Kalergis AM, Michea L. Spironolactone decreases doca-salt-induced organ damage by blocking the activation of t helper 17 and the downregulation of regulatory t lymphocytes. Hypertension. 2014;63:797–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tipton AJ, Baban B, Sullivan JC. Female spontaneously hypertensive rats have greater renal anti-inflammatory t lymphocyte infiltration than males. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2012;303:R359–367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tipton AJ, Baban B, Sullivan JC. Female spontaneously hypertensive rats have a compensatory increase in renal regulatory t cells in response to elevations in blood pressure. Hypertension. 2014;64:557–564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sullivan JC, Semprun-Prieto L, Boesen EI, Pollock DM, Pollock JS. Sex and sex hormones influence the development of albuminuria and renal macrophage infiltration in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R1573–1579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baan CC, van Gelder T, Balk AH, Knoop CJ, Holweg CT, Maat LP, Weimar W. Functional responses of t cells blocked by anti-cd25 antibody therapy during cardiac rejection. Transplantation. 2000;69:331–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ugrasbul F, Moore WV, Tong PY, Kover KL. Prevention of diabetes: Effect of mycophenolate mofetil and anti-cd25 on onset of diabetes in the drbb rat. Pediatr Diabetes. 2008;9:596–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xia J, Jiang X, Huang Y, Zhang K, Xiao S, Yang C. Anti-cd25 monoclonal antibody modulates cytokine expression and prolongs allografts survival in rats cardiac transplantation. Chin Med J (Engl). 2003;116:432–435 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caillon A, Schiffrin EL. Role of inflammation and immunity in hypertension: Recent epidemiological, laboratory, and clinical evidence. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2016;18:21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor LE, Gillis EE, Musall JB, Baban B, Sullivan JC. High-fat diet-induced hypertension is associated with a proinflammatory t cell profile in male and female dahl salt-sensitive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2018;315:H1713–H1723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watts SW, Darios ES, Mullick AE, Garver H, Saunders TL, Hughes ED, Filipiak WE, Zeidler MG, McMullen N, Sinal CJ, Kumar RK, Ferland DJ, Fink GD. The chemerin knockout rat reveals chemerin dependence in female, but not male, experimental hypertension. FASEB J. 2018:fj201800479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dai SY, Peng W, Zhang YP, Li JD, Shen Y, Sun XF. Brain endogenous angiotensin ii receptor type 2 (at2-r) protects against doca/salt-induced hypertension in female rats. J Neuroinflammation. 2015;12:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giachini FR, Sullivan JC, Lima VV, Carneiro FS, Fortes ZB, Pollock DM, Carvalho MH, Webb RC, Tostes RC. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 activation, via downregulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase 1, mediates sex differences in desoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertension vascular reactivity. Hypertension. 2010;55:172–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawanishi H, Hasegawa Y, Nakano D, Ohkita M, Takaoka M, Ohno Y, Matsumura Y. Involvement of the endothelin et(b) receptor in gender differences in deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt-induced hypertension. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2007;34:280–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.David FL, Montezano AC, Reboucas NA, Nigro D, Fortes ZB, Carvalho MH, Tostes RC. Gender differences in vascular expression of endothelin and et(a)/et(b) receptors, but not in calcium handling mechanisms, in deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertension. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2002;35:1061–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tostes RC, David FL, Carvalho MH, Nigro D, Scivoletto R, Fortes ZB. Gender differences in vascular reactivity to endothelin-1 in deoxycorticosterone-salt hypertensive rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2000;36:S99–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tostes Passaglia RC, David FL, Fortes ZB, Nigro D, Scivoletto R, Catelli De Carvalho MH. Deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertensive rats display gender-related differences in et(b) receptor-mediated vascular responses. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:1092–1098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stallone JN. Mesenteric vascular responses to vasopressin during development of doca-salt hypertension in male and female rats. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:R40–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Montezano AC, Callera GE, Mota AL, Fortes ZB, Nigro D, Carvalho MH, Zorn TM, Tostes RC. Endothelin-1 contributes to the sexual differences in renal damage in doca-salt rats. Peptides. 2005;26:1454–1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elmarakby AA, Quigley JE, Imig JD, Pollock JS, Pollock DM. Tnf-alpha inhibition reduces renal injury in doca-salt hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294:R76–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boesen EI, Williams DL, Pollock JS, Pollock DM. Immunosuppression with mycophenolate mofetil attenuates the development of hypertension and albuminuria in deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertensive rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2010;37:1016–1022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zimmerman MA, Baban B, Tipton AJ, O’Connor PM, Sullivan JC. Chronic ang ii infusion induces sex-specific increases in renal t cells in sprague-dawley rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2015;308:F706–712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwekel JC, Desai VG, Moland CL, Vijay V, Fuscoe JC. Life cycle analysis of kidney gene expression in male f344 rats. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kwekel JC, Desai VG, Moland CL, Vijay V, Fuscoe JC. Sex differences in kidney gene expression during the life cycle of f344 rats. Biol Sex Differ. 2013;4:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Banek CT, Gauthier MM, Van Helden DA, Fink GD, Osborn JW. Renal inflammation in doca-salt hypertension. Hypertension. 2019;73:1079–1086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ko SF, Yip HK, Zhen YY, Hung CC, Lee CC, Huang CC, Ng SH, Chen YL, Lin JW. Renal damages in deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertensive rats: Assessment with diffusion tensor imaging and t2-mapping. Mol Imaging Biol. 2019. 22(1);94–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fernandes R, Garver H, Harkema JR, Galligan JJ, Fink GD, Xu H. Sex differences in renal inflammation and injury in high-fat diet-fed dahl salt-sensitive rats. Hypertension. 2018;72:e43–e52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gaowa S, Zhou W, Yu L, Zhou X, Liao K, Yang K, Lu Z, Jiang H, Chen X. Effect of th17 and treg axis disorder on outcomes of pulmonary arterial hypertension in connective tissue diseases. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014:247372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Joller N, Lozano E, Burkett PR, Patel B, Xiao S, Zhu C, Xia J, Tan TG, Sefik E, Yajnik V, Sharpe AH, Quintana FJ, Mathis D, Benoist C, Hafler DA, Kuchroo VK. Treg cells expressing the coinhibitory molecule tigit selectively inhibit proinflammatory th1 and th17 cell responses. Immunity. 2014;40:569–581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eller K, Kirsch A, Wolf AM, Sopper S, Tagwerker A, Stanzl U, Wolf D, Patsch W, Rosenkranz AR, Eller P. Potential role of regulatory t cells in reversing obesity-linked insulin resistance and diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 2011;60:2954–2962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lu X, Crowley SD. Inflammation in salt-sensitive hypertension and renal damage. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2018;20:103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kasal DA, Barhoumi T, Li MW, Yamamoto N, Zdanovich E, Rehman A, Neves MF, Laurant P, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. T regulatory lymphocytes prevent aldosterone-induced vascular injury. Hypertension. 2012;59:324–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crowley SD, Song YS, Lin EE, Griffiths R, Kim HS, Ruiz P. Lymphocyte responses exacerbate angiotensin ii-dependent hypertension. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298:R1089–1097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Muller DN, Shagdarsuren E, Park JK, Dechend R, Mervaala E, Hampich F, Fiebeler A, Ju X, Finckenberg P, Theuer J, Viedt C, Kreuzer J, Heidecke H, Haller H, Zenke M, Luft FC. Immunosuppressive treatment protects against angiotensin ii-induced renal damage. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1679–1693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Madhur MS, Lob HE, McCann LA, Iwakura Y, Blinder Y, Guzik TJ, Harrison DG. Interleukin 17 promotes angiotensin ii-induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. Hypertension. 2010;55:500–507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ji H, Pai AV, West CA, Wu X, Speth RC, Sandberg K. Loss of resistance to angiotensin ii-induced hypertension in the jackson laboratory recombination-activating gene null mouse on the c57bl/6j background. Hypertension. 2017;69:1121–1127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Noyan F, Zimmermann K, Hardtke-Wolenski M, Knoefel A, Schulde E, Geffers R, Hust M, Huehn J, Galla M, Morgan M, Jokuszies A, Manns MP, Jaeckel E. Prevention of allograft rejection by use of regulatory t cells with an mhc-specific chimeric antigen receptor. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:917–930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Desreumaux P, Foussat A, Allez M, Beaugerie L, Hebuterne X, Bouhnik Y, Nachury M, Brun V, Bastian H, Belmonte N, Ticchioni M, Duchange A, Morel-Mandrino P, Neveu V, Clerget-Chossat N, Forte M, Colombel JF. Safety and efficacy of antigen-specific regulatory t-cell therapy for patients with refractory crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1207–1217 e1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marek-Trzonkowska N, Mysliwiec M, Dobyszuk A, Grabowska M, Techmanska I, Juscinska J, Wujtewicz MA, Witkowski P, Mlynarski W, Balcerska A, Mysliwska J, Trzonkowski P. Administration of cd4+cd25highcd127- regulatory t cells preserves beta-cell function in type 1 diabetes in children. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1817–1820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.