Abstract

Introduction

Atherosclerosis (ATH), the build up of fat in the arteries, is a principal cause of heart attack and stroke. Drug instability and lack of target specificity are major drawbacks of current clinical therapeutics. These undesirable effects can be eliminated by site-specific drug delivery. The endothelial surface over ATH lesions has been shown to overexpress vascular cell adhesion molecule1 (VCAM1), which can be used for targeted therapy.

Methods

Here, we report the synthesis, characterization, and development of anti VCAM1-functionalized liposomes to target cells overexpressing VCAM1 under static and flow conditions. Liposomes were composed of dioleoyl-phosphatidylcholine, sphingomyelin, cholesterol, and distearoyl-phosphatidylethanolamine-polyethylene glycol-cyanur (31.67:31.67:31.67:5 mol%). VCAM1 expression in endothelial cells was induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) treatment.

Results

Characterization study revealed that liposomes were negatively charged (− 7.7 ± 2.6 mV) with an average diameter of 201.3 ± 3.3 nm. Liposomes showed no toxicity toward THP-1 derived macrophages and endothelial cells. Liposomes were able to target both fixed and non-fixed endothelial cells, in vitro, with significantly higher localization observed in non-fixed conditions. To mimic biological and physiologically-relevant conditions, liposome targeting was also examined under flow (4 dyn/cm2) with or without erythrocytes (40% v/v hematocrit). Liposomes were able to target LPS-treated endothelial cells under dynamic culture, in the presence or absence of erythrocytes, although targeting efficiency was five-fold lower in flow compared to static conditions.

Conclusions

This liposomal delivery system showed a significant improvement in localization on dysfunctional endothelium after surface functionalization. We conclude that VCAM1-functionalized liposomes can target and potentially deliver therapeutic compounds to ATH regions.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, Cell adhesion molecules, Drug delivery, Endothelium, Nanomedicine

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is currently the leading cause of death in the United States, with more than 840,000 new cases annually.6 Atherosclerosis (ATH) refers to the process of plaque formation within the walls of the arteries and is a multifactorial disease involving both genetic and environmental causes. ATH plaques form by lipid accumulation in the intimal region of an artery, under dysfunctional endothelium monolayers.20 This endothelial injury causes the accumulation of both monocytes and T-cells to the affected endothelium.8 Following adhesion, monocytes migrate into the subendothelial space and transform into cholesterol-laden cells. The inflammatory responses are amplified by the increased number of local macrophages, commonly known as foam cells, which further contribute to the progression of the ATH plaque, thereby aggravating the disease.34

Despite the high incidence and clinical importance of ATH, the current treatment options for the disease are insufficient. Current standard drugs induce undesirable effects such as insulin resistance and type II diabetes.17 Also, the plasma elimination half-life of atorvastatin, fluvastatin and other statins are shorter than 16 h, due to protein-binding in the serum and rapid take-up by the liver.4,25 This has led to increasing interest in the development of targeted strategies for treating ATH. Yoon et al.45 have conducted an in vitro fibrin targeting study under static condition. In this experimental study, cysteine-arginine-glutamic acid-lysine-alanine (CREKA) conjugated nanoparticles have displayed almost 8 times increased targeting efficiency compared to the control micelles.45 In another study, Winter et al.44 focused on utilizing solid nanoparticles for specific delivery of drugs to the site of atherosclerotic plaques. However, the use of solid nanoparticles, such as paramagnetic perfluorocarbon44 leads to slow release of drugs as the particles degrade to release intracellular content. While other nanocarriers have been examined for drug delivery in ATH, such studies have generally used non-biodegradable carriers,16 focused on targeting macrophages, which are underneath the endothelium and not directly accessible to nanoparticles,10 or examined in vitro cultures in static conditions,9,29 not considering the fact that atherosclerotic plaques are subject to blood flow.

It is known that the endothelial cell surface of atheroma overexpresses vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM1).15,27,39 This molecule has already been utilized in a few drug delivery efforts. Sun and colleagues have studied conjugation of an atherogenic miRNA inhibitory drug to the surface of anti-VCAM1 functionalized gold nanospheres for delivery to endothelial cells.42 Our group has also previously shown the possibility of targeting VCAM1 for delivery of solid particles to the site of atherosclerotic plaques.16 Soft particles have also been investigated for VCAM1 targeting. The in vitro and in vivo specificity of anti-VCAM1 functionalized peptide amphiphiles have been studied by Mlinar et al.33 In addition, Pan et al.38 have investigated the in vivo targeting of anti-VCAM1 functionalized perfluorocarbon nanoparticles in the mouse models of ATH. Given the promise of soft particles for drug delivery by targeting VCAM1, it is possible that a liposomal system could be advantageous in the context of drug delivery in ATH, given that drug release in liposomes upon their cellular uptake is faster than solid particles.14 However, prior to utilizing liposomal nanocarriers for drug delivery in animal models of ATH, it is important to ensure that such carriers are not toxic to cells associated with the plaque, are capable of targeting dysfunctional endothelium, and that targeting can be achieved under both static and dynamic conditions.

In the current study, a liposomal formulation, conjugated to antibody against VCAM1, was evaluated for its ability to target inflamed human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), under both static and dynamic conditions. The liposomal system was not toxic for macrophage or endothelial cells in vitro and was able to target both fixed and non-fixed endothelial cells overexpressing VCAM1 in static conditions. Endothelial cell targeting was observed at almost the same level for medium with and without erythrocytes under flow (4 dyn/cm2), albeit to a lower degree compared to static conditions. These results suggest that liposomal systems could be potentially used for drug delivery in animal models of ATH, which is a focus of future studies.

Materials and Methods

Dioleoyl-phosphatidylcholine (DOPC), sphingomyelin (SM), cholesterol (Chol), and phosphatidylethanolamine-polyethylene glycol (2000 kDa)-cyanur (DSPE-PEG(2000)-Cyanur) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL, USA). Sephadex G-25 in PD-10 desalting columns were purchased from GE Healthcare (Buckinghamshire, UK). Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial (HUVEC) Cells (C2519A) and EGM-2 BulletKits media (CC-3162) were purchased from Lonza (Allendale, NJ, USA). Human erythrocytes (SER-PRBC) were purchased from ZenBio (Research Triangle Park, NC, USA). Mouse normal IgG and polyclonal anti-vascular cell adhesion molecule1 (anti-VCAM1) antibody were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). Goat anti-mouse IgG, mouse IgG1 kappa isotype control and FITC conjugated VCAM1 antibody and trypan blue stain were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Chloroform, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), Tris buffer and other solvents were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Liposome Preparation

Liposomes were synthesized by hydrating dry lipid films. Lipid solutions were made by dissolving DOPC, SM, Chol, and DSPE-PEG (2000)-Cyanur (31.67:31.67:31.67:5 mol%) in chloroform. Liposomes were synthesized using the established, freeze–thaw method.36 Briefly, lipid mixture was dehydrated under nitrogen gas to obtain a thin lipid film on the wall of glass test tubes. Lipid film was rehydrated with PBS buffer followed by vortex mixing to obtain a liposomal suspension with a final concentration of 0.2 mg/mL. The process was completed using seven freezing and thawing cycles by freezing the lipid solution in a dry ice, acetone bath followed by thawing in water bath at 40 °C for 3 min. Characterization of size and surface charge of liposomes were measured using a particle sizer (Zeta Sizer Nano ZS, Malvern Instrument Inc., Worcestershire, UK).

Liposome Leakage Assay

The stability of liposome was studied by fluorometry using carboxyfluorescein(CF) as the fluorescent probe, as reported previously.3 To encapsulate CF in the vesicles, lipid films were rehydrated using 80 mM CF solution dissolved in PBS. Encapsulation was completed after 7 cycles of freeze–thaw. Unconjugated CF was separated using the Sephadex PD-10 separation column. Stability of liposomes was investigated at 37 °C under stirring by monitoring the fluorescence intensity of the released CF at 517 nm. CF fluorescence is self-quenched when encapsulated inside liposomes at high concentration. Loss of liposome integrity over time results in the release of CF and an increase in fluorescence intensity. The total fluorescence intensity was obtained by disrupting the liposomes by adding 10 μL of Triton X-100 detergent in 2 mL of liposomal solution. The percentage of release at each sampling time was calculated by dividing the fluorescence intensity for that time point by the total release intensity of each experiment.

Liposome Cytotoxicity Study

Cytotoxicity of liposomes in HUVEC and THP-1 cell lines was evaluated using the Trypan Blue cell viability assay. In brief, confluent monolayers of HUVEC and THP-1 cells were prepared in 6-well plates with specific media (EGM-2 and DMEM, respectively) and incubated with three different concentrations of liposome suspension (0.2, 0.02 and 0.002 mM). For the Trypan Blue assay, cells were exposed to liposomes for 12 or 24 h. After incubation, cells were detached, using 0.025% trypsin solution, and collected. Trypan Blue staining was used to detect and count colorless viable cells with intact membrane, vs. the distinctive blue dyed dead cells with damaged membranes.

Liposome Surface Functionalization

Antibody conjugation to the surface of liposomes was accomplished based on the direct-coupling method introduced by Bendas et al.5 Direct-coupling process provides a stable covalent bond between the N-terminus of the antibody and the distal end of the PEG terminus on the surface of the liposomes. Briefly, liposomes were hydrated using the Tris buffer at a pH of 8.8 and normal mouse IgG was added at a 1:1000, antibody to lipid molar ratio, for 16 h at room temperature. The unbound antibody was separated using centrifugation at 60,000×g. Liposomes were washed twice using the Tris buffer.

A mouse IgG ELISA kit assay was used to determine antibody conjugation efficiency on liposome surfaces. This kit is an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the quantitative measurement of mouse IgG conjugated liposomes using the horseradish peroxidase conjugated anti-mouse IgG detector antibody. Further characterization of antibody conjugation was performed using an inverted fluorescence microscope (ECLIPSE Ti, Nikon Instruments Inc., Tokyo, Japan) with a 0.52 projection lens (Nikon Instruments Inc., Tokyo, Japan) and 40× Fluor objective lens. To this aim, fluorescence microscopy was applied to analyze antibody liposome conjugation using the secondary fluorescent. DyLight-488 conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG was used at a 1:500 final volume dilution for 1 h at room temperature. Rhodamine-DOPE (2 mol%) was incorporated in the liposome structure to allow for fluorescence visualization.

VCAM1 Expression Study

Previous studies have shown that lipopolysaccharide (LPS) can imitate inflammatory condition by inducing VCAM1 overexpression in endothelial cells.13,22,29 A similar method was used in the current study to induce VCAM1 overexpression in HUVEC cells. HUVEC cells were seeded on 10 mm glass coverslips and cultured for 24 h in a 6 well plate. Cells were treated with 100 ng/mL of LPS in the culture medium for 24 h. Afterwards, cells were fixed with formaldehyde and incubated with FITC conjugated anti-VCAM1 at a 1:200 final volume dilution for 30 min in PBS. Then, cells were imaged using a Nikon A1R confocal laser scanning microscope system and the expression of VCAM1 was estimated by measuring the level of the fluorescence (FITC) intensity, using the ImageJ software.1 Cells not treated with LPS were used as negative control. Kappa fluorescent antibody was used as an isotype antibody for positive control.

Liposome Targeting Under Static Conditions

In order to stimulate VCAM1 surface overexpression, HUVEC cells (passage number 3–8) were cultured in a 35-mm tissue culture plate and treated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 24 h prior to the experiment. The specificity of the anti-VCAM1 functionalized liposomes to LPS-stimulated HUVEC cells was analyzed by measuring the final liposomal localization. HUVEC cells were seeded on glass cover slips and treated with 100 ng/mL LPS for 24 h. Cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde and incubated for 30 min with 0.2 mM liposome suspension in PBS solution under static culture conditions at room temperature. Liposomes included 2 mol% rhodamine-DOPE in their structure to allow for fluorescence visualization. Studies were repeated without fixation to ensure that cell fixation, and the resulting protein crosslinking by formaldehyde, did not artificially modify binding. For these studies, cells were incubated with functionalized liposomes (0.2 mM) for 6 h at 37 °C before fixation to compare liposome targeting between fixed and non-fixed cells by confocal macroscopy with the rhodamine-based fluorescent measurement using the ImageJ software.

Liposome Targeting Under Flow Condition

A three-dimensional, well-controlled flow chamber device was used to study liposome targeting to endothelial cells under flow conditions. Also, the possible interaction of functionalized liposomes with human red blood cells was investigated by adding erythrocytes, at 40% hematocrit (i.e., erythrocyte volume/total volume) into the flow chamber. A silicon rubber gasket was used to produce a cut-out channel with 0.5 cm width and 178 μm depth with a polycarbonate cover on top of gasket, using a previously established method.40 This transparent polycarbonate disk was placed on top of the cell culture dish and provided a leak-proof seal using a vacuum pump to allow fluorescent microscopic visualization. Fluorescent (rhodamine-conjugated) liposomes were suspended in EGM medium (0.2 mM) and perfused over HUVEC cells for 3 min with an average shear stress of 4 dyn/cm2, as a representative shear stress for arterial blood flow in ATH lesion-prone.30 An inverted-stage microscope (Leica, DMI6000B) with 0.55× projection lens (Leica Microsystems, Mannheim, Germany) and 10× fluor objective were used to study liposomes targetability at room temperature and 4 dyn/cm2 wall shear stress in the described system. Finally, fluorescence microscopy images were analyzed with ImageJ to quantify localized liposomes after washing the cells with pure medium flow for 30 s.

Results

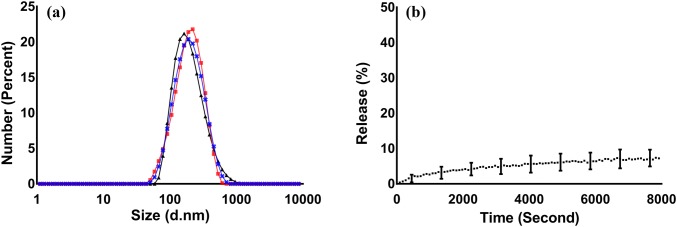

Liposomes were composed of three lipid components: dioleoyl-phosphatidylcholine (DOPC), sphingomyelin (SM), and cholesterol (Chol). This liposome composition was selected due to its stability at physiological temperature, as shown in Fig. 1. Liposomes included PEG groups as PEGylation is known to increase the circulation time in vivo.41 Liposomes were characterized for size, charge, and stability at 37 °C using dynamic light scattering and laser Doppler anemometry. Liposomes had a mean diameter of 201.3 ± 3.3 nm and a surface charge of − 7.7 ± 2.6 mV, and a narrow size distribution as determined by size distribution graphs, in PBS at 7.4 pH (Fig. 1a). The stability of liposomes at 37 °C was examined by monitoring the release of the self-quenching fluorescent dye, CF, from their lumen. This study showed that almost 7% of CF was released from the liposomes after two hours of incubation in PBS (Fig. 1b), suggesting minimal release of the liposome content prior to uptake by cells, which has been reported to take more than 15 min following intravenous injection.16

Figure 1.

Characterization of (a) liposome size distribution, showing the overlay of three independent size distribution measurements by dynamic light scattering and (b) liposome stability as measured by the release of the self-quenching probe, CF, from the lumen of the vesicles. All measurements were performed in PBS, at 37 °C, and pH of 7.4. Error bars represent the standard deviation of at least three independent measurements.

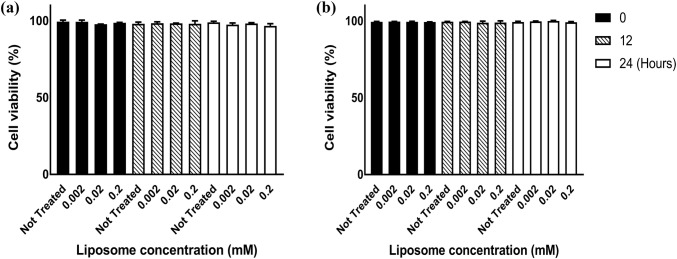

Next, the effect of liposomes on cell viability was examined in two of the major cell types found in ATH plaques, macrophages (derived from THP-1 monocytes), and endothelial cells (HUVEC). The Trypan Blue exclusion assay, which examines membrane integrity, was used to evaluate cell viability after exposure to liposomes. Cells were exposed to liposomes at various concentrations (0.002, 0.02, 0.2 mM) and cell viability was examined for 24 h using the Trypan Blue dye. This assay confirmed the lack of cytotoxicity by liposomes. The cell viability, for both THP-1 and HUVEC cells, remained at approximately 100% for 12 and 24 h after the exposure to all concentrations of liposomes (Figs. 2a and 2b).

Figure 2.

Cell cytotoxicity for (a) HUVEC and (b) THP-1 cells as measured by the Trypan Blue assay. Bar graphs show liposome viability for not-treated cells and cells treated with 0.002, 0.02, and 0.2 mM of liposomes. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

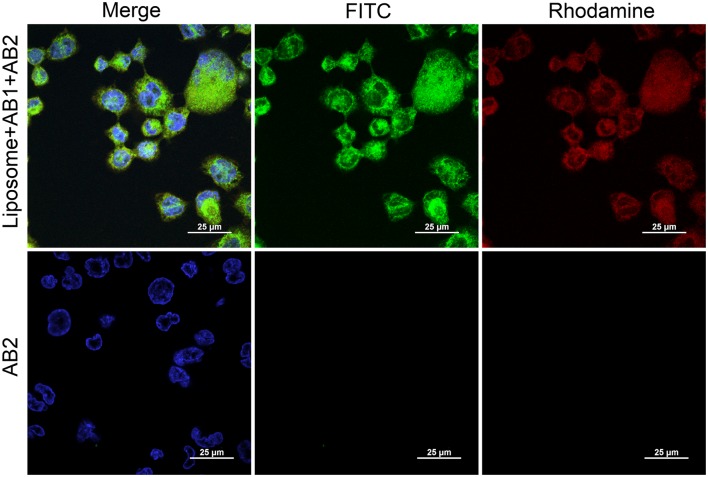

Upregulation of VCAM1 in the endothelial cell has been shown to be directly related to the process of the plaque formation and the pathogenesis of ATH.35 Therefore, this cell surface motif could be a suitable target for site-specific delivery. To prepare a VCAM1-specific delivery system, liposomes were functionalized by coupling anti-VCAM1 antibody to the PEG terminus of liposomal surface in a molar ratio of 1:1:1:0.16 (DOPC:SM:Chol:DSPE-PEG-Cyanur). Quantification of antibody–liposome coupling efficiency was performed using the mouse IgG antibody. Antibody conjugation to cyanur in DSPE-PEG-cyanur was achieved by incubating the liposomes with the antibody at a protein:lipid ratio of 1:1000 for 16 h at room temperature.18 Excess, unconjugated antibodies were separated via centrifugation and removed after two Tris solution washes. Conjugation was confirmed using an ELISA assay kit to measure antibody conjugation to liposomes. A conjugation efficiency of 57.8 ± 8.4% was determined from the absorption spectrum of samples at 450 nm and total initial antibody concentration. This coupling efficiency is similar to the previously published coupling range which has been reported to be between 30% to 50% antibody-liposome binding efficiency.5,23,31 Conjugation of antibody to the surface of the liposomes was also examined using confocal microscopy. For this experiment, a FITC-conjugated secondary antibody was added to functionalized liposomes. Microscopy images showed significant co-localization between rhodamine (red) and fluorescein (green), which respectively represent labeled liposomes and FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (Fig. 3—left column). This co-localization of liposomes and secondary antibodies further confirmed antibody conjugation to the surface of the liposomes. In addition, liposomes showed significant uptake in THP-1 macrophages (Fig. 3—top right column). No secondary antibody localization was observed in THP-1 cells when secondary antibodies were added to cells without conjugating them to functionalized liposomes (Fig. 3—middle column).

Figure 3.

Conjugation of normal mouse IgG antibody (AB1) to the surface of liposomes as examined by confocal fluorescence microscopy on a background of THP-1 cells. Cells were stained with DAPI (blue), while liposomes were stained with rhodamine (red), and the secondary antibody (AB2) was conjugated to FITC (green). The top row shows successful conjugation of antibody to the surface of the liposomes, as well as the uptake of liposomes in THP-1 macrophages. Bottom row shows liposomes not conjugated with normal mouse IgG antibody, in which no binding of the secondary antibody was observed. Scale bar = 25 μm.

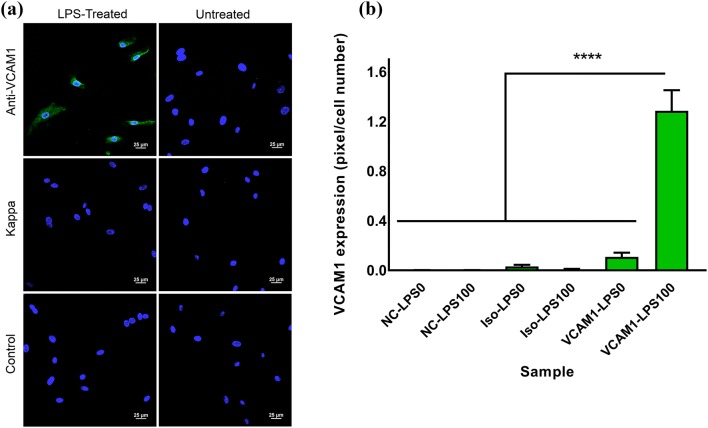

VCAM1 overexpression in HUVEC cells was stimulated using LPS treatment to mimic pro-inflammatory conditions in ATH,29 which results in VCAM1 upregulation. Incubating HUVEC cells with 100 ng/mL LPS for 24 h led to significant VCAM1 expression. This was confirmed by incubating HUVEC cells with anti-VCAM1 antibody, followed by a FITC-conjugated secondary antibody, and measuring the FITC fluorescence signal (Fig. 4a). This fluorescence signal was quantified based on the percentage of fluorescent pixels in these images, divided by the total number of counted cells. VCAM1 expression level of LPS-activated HUVEC cells was approximately 12 times more than un-treated cells and significantly higher than all other groups (Fig. 4b). FITC-conjugated isotype control (Kappa antibody) samples illustrated significantly lower fluorescence pixels, demonstrating negligible non-specific binding.

Figure 4.

(a) VCAM1 expression in LPS-treated (100 ng/mL), left column, or untreated, right column, HUVEC cells. Confocal imaging with FITC (green) staining for anti-VCAM1 secondary antibody and Kappa isotype antibody. Scale bar = 25 μm. (b) Fluorescence intensity measurement using the ImageJ software based on the number of green pixels per number of cells, indicating relative expression of cellular VCAM1. NC-LPS0: negative control cells without LPS treatment, NC-LPS100: negative control cells with 100 ng/mL LPS treatment, Iso-LPS0: isotype Kappa secondary antibody without LPS treatment, Iso-LPS100: Isotype Kappa secondary antibody with 100 ng/mL LPS treatment, VCAM1-LPS0: VCAM1 secondary antibody without LPS treatment, VCAM1-LPS100: VCAM1 secondary antibody with 100 ng/mL LPS treatment. Error bars represent the standard error and **** indicates p < 0.00001.

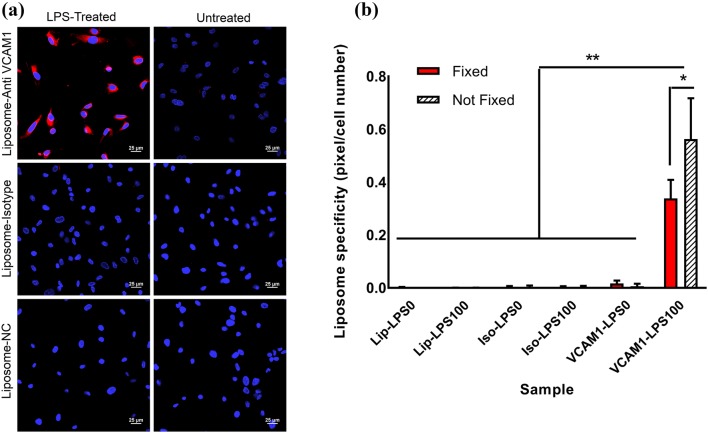

Anti-VCAM1 conjugated liposomes were used to target LPS-treated HUVEC cells overexpressing VCAM1. To this aim, LPS-treated and non-treated endothelial cell monolayers were prepared, fixed, and incubated with unfunctionalized (negative control), mouse IgG-functionalized (isotype control), and VCAM1-functionalized liposomes for six hours at 37°C. The fluorescent lipid, rhodamine-DOPE, was incorporated in the structure of all liposomes to allow for fluorescence observations. Liposome localization with LPS-treated or non-treated cells was evaluated using confocal microscopy and quantified by dividing the percentage of pixels showing rhodamine fluorescence by the total cell number, labeled with DAPI, using the ImageJ software. VCAM1-functionalized liposomes showed at least 20 times higher localization to HUVEC cells compared to non-functionalized liposomes or liposomes functionalized with isotype control (Figs. 5a and 5b). Liposome co-localization was only observed when HUVEC cells were treated with LPS, demonstrating that localization was due to the overexpression of VCAM1, leading to successful targeting of liposomes to the LPS-treated HUVEC cells. Importantly, targeting was not limited to fixed cells. When the experiment was repeated for HUVEC cells that had not been fixed, an even higher extent of localization, ~ 67% higher compared to fixed cells, between VCAM1 functionalized liposomes and LPS-treated cells was observed (Figs. 5a and 5b).

Figure 5.

Functionalized liposome localization in normal (non-treated) and LPS-treated (100 ng/mL) HUVEC cells. (a) Confocal imaging showing liposome attachment to, or internalization in, HUVEC cells for anti-VCAM1-conjugated liposomes, isotype (IgG)-conjugated-liposomes, and liposome with no antibody attachment (negative control or NC). Cells were stained with DAPI (blue) while liposomes were stained with rhodamine (red). Scale bar = 25 μm. (b) Quantification of results in A for both fixed and not-fixed HUVEC cells based on the fluorescence intensity measurements using the ImageJ software. Lip-LPS0: cells treated with control unfunctionalized liposomes, without LPS treatment; Lip-LPS100: cells treated with control unfunctionalized liposomes, and 100 ng/mL LPS treatment; Iso-LPS0: cells treated with isotype antibody functionalized liposomes, without LPS treatment; Iso-LPS100: cells treated with isotype antibody functionalized liposomes, and 100 ng/mL LPS treatment; and VCAM1-LPS0: cells treated with anti-VCAM1-functionalized liposomes, without LPS treatment; VCAM1-LPS100: cells treated with anti-VCAM1-functionalized liposomes, and 100 ng/mL LPS treatment. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the measurements. * and ** indicates p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively.

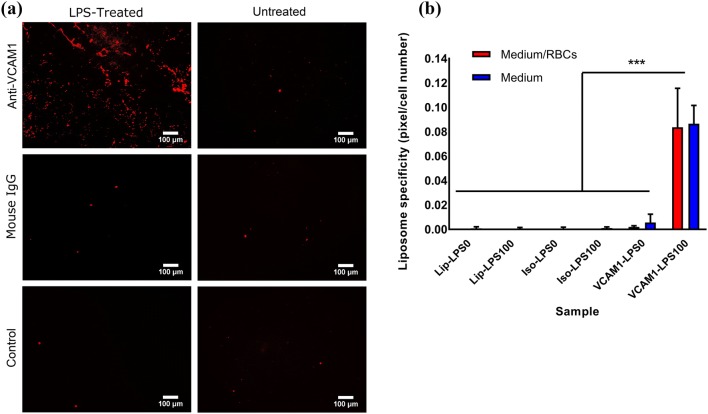

Studies with VCAM1-functionalized liposomes confirmed successful targeting of HUVEC cells overexpressing VCAM1 in both fixed and non-fixed conditions. To examine targeting under shear flow, a parallel plate flow chamber, as described in the study of Shirure et al.40 was used. High expression of VCAM1 in HUVEC cells was again stimulated using LPS treatment (100 ng/mL) after HUVEC cells were cultured for 24 h in 35 mm cell culture dishes. Then, the specificity of functionalized liposomes to VCAM1 was analyzed by suspending rhodamine-labeled liposomes, in the EGM medium used to grow HUVEC cells, and perfusing them using a syringe pump for 3 min over HUVEC cells. A shear stress of 4 dyn/cm2, representative of the arterial vessel regions with higher risk of forming carotid atherosclerosis plaque was used,30 followed by 30 s of washing with the cell culture medium. Liposome targeting was determined by confocal imaging and evaluating the fluorescence of bound liposomes using the ImageJ software. These results showed significantly higher localization of anti VCAM1 functionalized liposomes in LPS treated cells, compared to untreated cells, isotype control, and unfunctionalized liposomes. However, functionalized liposomes showed about six-fold lower localization under flow condition compared to the static culture. This finding confirmed the high targeting capacity of VCAM1-functionalized liposomes to the surface of the inflamed HUVEC cells under both static and simulated blood flow condition. To evaluate whether blood components might affect the binding of liposomes to the site of the plaque, experiments were performed under shear flow in the presence of erythrocytes. No significant difference in the binding of vesicles to LPS-treated epithelial was observed in the presence or absence of erythrocytes (Fig. 6b), indicating that the presence of erythrocytes does not disturb the ability of vesicles to target VCAM1.

Figure 6.

Localization of functionalized liposomes under flow condition in normal (non-treated) and LPS-treated (100 ng/mL) HUVEC cells in the presence of erythrocytes (medium + erythrocytes) or in their absence (medium). (a) Confocal imaging and staining with Rhodamine (Red) for liposomes for anti-VCAM1-conjugated-liposomes, isotype (IgG)-conjugated-liposomes and non-functionalized liposomes (control). Scale bar is 100 μm. (b) Fixed and not-fixed HUVEC cells targetability study based on the fluorescence intensity measurement using the ImageJ software for Lip-LPS0: cells treated with control unfunctionalized liposomes, without LPS treatment; Lip-LPS100: cells treated with control unfunctionalized liposomes, and 100 ng/mL LPS treatment; Iso-LPS0: cells treated with isotype antibody functionalized liposomes, without LPS treatment; Iso-LPS100: cells treated with isotype antibody functionalized liposomes, and 100 ng/mL LPS treatment; and VCAM1-LPS0: cells treated with VCAM1 functionalized liposomes, without LPS treatment; VCAM1-LPS100: cells treated with VCAM1 functionalized liposomes, and 100 ng/mL LPS treatment. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the measurements and ***p < 0.001.

Discussion

In this study, development and characterization of a liposomal system for targeting of inflamed endothelial cells has been reported. The developed liposomes do not cause toxicity toward endothelial and macrophage cells and are able to maintain sufficient stability for targeting under blood flow condition. These liposomes, functionalized with antibody against VCAM1, were able to successfully target HUVEC cells overexpressing this protein under both static and dynamic conditions.

In developing liposomes for targeting ATH plaques, two important factors need to be considered. First, it is important for liposomes to not “leak” their content prior to reaching the plaque, so as to avoid significant systemic side effect. This was examined by investigating the leakage of a fluorescent probe from the lumen of the vesicles, which was confirmed to be minor (7% release after 2 h under stirring at 37 °C in PBS, Fig. 1). It should be noted that the intracellular release of the liposome content (i.e., after internalization) is expected to be significantly higher due to the cellular breakdown of liposomes.37 Secondly, it is important to consider the role of macrophages. This is because of the presence of a significant number of macrophages and foam cells in atherosclerotic plaque, which play an important role in the early stage and progression of the aortic ATH. Therefore, liposomes targeting endothelial cells would likely interact with, or get engulfed by, macrophages covering these cells. The liposomal carriers developed in this study showed no toxicity to either macrophages (Fig. 2a) or endothelial cells (Fig. 2b), even though they were internalized by macrophages in significant numbers (Fig. 3).

Previous studies have proven upregulation of endothelial VCAM1 from an early stage in ATH.2,12 In the current study, overexpression of VCAM1 was induced by LPS treatment (Fig. 4). LPS treatment is a common method to induce inflammation treatment,28 and has been used in a few previous studies to examine the role of VCAM1 and other adhesion molecules in myocardial dysfunction.7,15,24,46 While LPS treatment did not cause any observable toxicity in HUVEC cells in the current study, potential unwanted adverse effects on cellular function due to LPS treatment cannot be ruled out. Anti VCAM1-conjugated liposomes showed significant localization inside and on the surface of HUVEC cells (Fig. 5). Importantly, this binding was higher in non-fixed samples compared to fixed samples. This is expected as formaldehyde fixation is known to alter receptor–ligand interactions47; however, this finding is important as it implies that potentially higher targeting could be achieved in vivo where cell surface receptors are not structurally modified by the presence of fixatives.

While many studies have focused on cellular targeting by liposomes in vitro, the effect of shear flow on the efficiency of targeting is generally overlooked. In the current study, addition of shear stress in a parallel plate flow chamber decreased liposome localization in HUVEC cells by approximately five-fold. This effect could be attributed to the shear flow resulting in breaking the antibody-ligand binding or lower accessibility of the ligands in flow conditions. Previous studies have reported that shear stress affects and disrupts the function of the receptor-ligand bonds on the cell membrane.7,11,32 Flow conditions have been shown to induce differences in the expression of adhesion molecules,26 which can explain the difference in liposome localization. However, contrasting results also exist. Evans et al. have suggested that the introduction of flow increase the catch-bond characteristics of VCAM1 bonds on the plasma membrane.19 While it is possible that shear stress enhances the catch-bond property of VCAM1 receptors, the results of the current study show a significant reduction in liposome binding and internalization under flow conditions. It is possible that the increase in the catch-bond is not significant enough to hold the liposomes after perfusion has been applied. This is in line with the study of Finger et al.,21 demonstrating that T lymphocytes form stable tethers in a VCAM1 functionalized surface in a flow chamber, in shear stress values lower than 1.8 dyn/cm2, but increasing the shear stress reduces bond stability. Therefore, VCAM1 bonds are sensitive to fluid shear stress in vitro and may vanish at higher shear stress values.

Due to the abundance of erythrocytes in blood, it is important to consider and explore their possible interactions with nanoparticles designed for therapeutic delivery. Simulation approaches have demonstrated that the tumbling movement of erythrocytes in blood vessels increases nanoparticle dispersion in the vein, thereby increasing nanoparticle concentration closer to the vessel wall.43 The level of nanoparticle binding to the walls increases by ~ 50% after the addition of erythrocytes to the system. Therefore, we investigated the effect of erythrocytes on the ability of functionalized liposomes to target endothelial cells overexpressing VCAM1 was examined. However, the presence of erythrocytes did not affect the ability of functionalized liposomes to bind to HUVEC cells overexpressing VCAM1, with no statistical difference observed in the experiments with or without erythrocytes (Fig. 6).

Taken together, our results indicate anti-VCAM1 antibody-functionalized liposomal system can effectively target inflamed endothelial cells overexpressing VCAM1 adhesion molecules under static and physiologically relevant conditions. Future studies are needed to examine the potential therapeutic application of this endothelium-targeting delivery system by encapsulating drugs to target and reverse or delay the progression of ATH.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI-R15HL133885) awarded to R.M. and A.F. We acknowledge the use of the Ohio University Heritage College Microscopy Core. The authors would like to thank Nicholas Cellars (Ohio University, Biomedical Engineering Program) and Nathan Reynolds (Ohio University, Translational Biomedical Science Program) for technical assistance.

Conflict of interest

Authors Mahsa Kheradmandi, Ian Ackers, Monica M. Burdick, Ramiro Malgor, and Amir M. Farnoud declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Standards

No human and animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Abramoff MD, Magalhaes PJ, Ram SJ. Image processing with ImageJ. Biophoton. Int. 2004;11:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ackers I, Malgor R. Interrelationship of canonical and non-canonical Wnt signalling pathways in chronic metabolic diseases. Diabetes Vasc. Dis. Res. 2018;15:3–13. doi: 10.1177/1479164117738442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adib AA, Nazemidashtarjandi S, Kelly A, Kruse A, Cimatu K, David AE, Farnoud AM. Engineered silica nanoparticles interact differently with lipid monolayers compared to lipid bilayers. Environ. Sci. Nano. 2018;5:289–303. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakker-Arkema RG, Best J, Fayyad R, Heinonen TM, Marais AD, Nawrocki JW, Black DM. A brief review paper of the efficacy and safety of atorvastatin in early clinical trials. Atherosclerosis. 1997;131:17–23. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(97)06066-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bendas G, Krause A, Bakowsky U, Vogel J, Rothe U. Targetability of novel immunoliposomes prepared by a new antibody conjugation technique. Int. J. Pharm. 1999;181:79–93. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(99)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Bittencourt MS. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139:e56–e528. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhowmick T, Berk E, Cui X, Muzykantov VR, Muro S. Effect of flow on endothelial endocytosis of nanocarriers targeted to ICAM-1. J Control Release. 2012;157:485–492. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.09.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bobryshev YV. Monocyte recruitment and foam cell formation in atherosclerosis. Micron. 2006;37:208–222. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao Z, Tong R, Mishra A, Xu W, Wong GC, Cheng J, Lu Y. Reversible cell-specific drug delivery with aptamer-functionalized liposomes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2009;48:6494–6498. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen W, Vucic E, Leupold E, Mulder WJ, Cormode DP, Briley-Saebo KC, Barazza A, Fisher EA, Dathe M, Fayad ZA. Incorporation of an apoE-derived lipopeptide in high-density lipoprotein MRI contrast agents for enhanced imaging of macrophages in atherosclerosis. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2008;3:233–242. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheung LSL, Konstantopoulos K. An analytical model for determining two-dimensional receptor-ligand kinetics. Biophys. J. 2011;100:2338–2346. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cybulsky MI, Iiyama K, Li H, Zhu S, Chen M, Iiyama M, Davis V, Gutierrez-Ramos JC, Connelly PW, Milstone DS. A major role for VCAM-1, but not ICAM-1, in early atherosclerosis. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2001;107:1255–1262. doi: 10.1172/JCI11871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Da Silva-Candal A, Brown T, Krishnan V, Lopez-Loureiro I, Ávila-Gómez P, Pusuluri A, Pérez-Díaz A, Correa-Paz C, Hervella P, Castillo J, Mitragotri S. Shape effect in active targeting of nanoparticles to inflamed cerebral endothelium under static and flow conditions. J Control Release. 2019;309:94–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Date AA, Joshi MD, Patravale VB. Parasitic diseases: liposomes and polymeric nanoparticles versus lipid nanoparticles. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2007;59:505–521. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davies MJ, Gordon JL, Gearing AJH, Pigott R, Woolf N, Katz D, Kyriakopoulos A. The expression of the adhesion molecules ICAM-1, VCAM-1, PECAM, and E-selectin in human atherosclerosis. Am. J. Pathol. 1993;171:223–229. doi: 10.1002/path.1711710311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deosarkar SP, Malgor R, Fu J, Kohn LD, Hanes J, Goetz DJ. Polymeric particles conjugated with a ligand to VCAM-1 exhibit selective, avid, and focal adhesion to sites of atherosclerosis. Biotechnol. Biomed. Eng. 2008;101:400–407. doi: 10.1002/bit.21885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doll R. Efficacy of cholesterol-lowering therapy in 18 686 people with diabetes in 14 randomised trials of statins: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2008;371:117–125. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60104-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elbahnasawy MA, Donius LR, Reinherz EL, Kim M. Co-delivery of a CD4 T cell helper epitope via covalent liposome attachment with a surface-arrayed B cell target antigen fosters higher affinity antibody responses. Vaccine. 2018;36:6191–6201. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evans E, Kinoshita K. Using force to probe single-molecule receptor–cytoskeletal anchoring beneath the surface of a living cell. Methods Cell Biol. 2007;83:373–396. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(07)83016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farhood H, Serbina N, Huang L. The role of dioleoyl phosphatidylethanolamine in cationic liposome mediated gene transfer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1995;1235:289–295. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(95)80016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finger EB, Purl KD, Alon R, Lawrence MB, von Andrian UH, Springer TA. Adhesion through L-selectin requires a threshold hydrodynamic shear. Nature. 1996;379:266. doi: 10.1038/379266a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galkina E, Ley K. Immune and inflammatory mechanisms of atherosclerosis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2009;27:165–197. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gosk S, Moos T, Gottstein C, Bendas G. VCAM-1 directed immunoliposomes selectively target tumor vasculature in vivo. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1778:854–863. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gu W, Yao L, Li L, Zhang J, Place AT, Minshall RD, Liu G. ICAM-1 regulates macrophage polarization by suppressing MCP-1 expression via miR-124 upregulation. Oncotarget. 2017;8:111882. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.22948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herd JA, West MS, Ballantyne C, Farmer J, Gotto AM. Baseline characteristics of subjects in the lipoprotein and coronary atherosclerosis study (LCAS) with fluvastatin. Am. J. Cardiol. 1994;73:D42–D49. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90632-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jung JJ, Grayson KA, King MR, Lamkin-Kennard KA. Isolating the influences of fluid dynamics on selectin-mediated particle rolling at venular junctional regions. Microvasc. Res. 2018;118:144–154. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2018.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khodabandehlou K, Masehi-Lano JJ, Poon C, Wang J, Chung EJ. Targeting cell adhesion molecules with nanoparticles using in vivo and flow-based in vitro models of atherosclerosis. Exp Biol Med. 2017;242:799–812. doi: 10.1177/1535370217693116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Konstantopoulos K, McIntire LV. Effects of fluid dynamic forces on vascular cell adhesion. J. Clin. Investig. 1996;98:2661–2665. doi: 10.1172/JCI119088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee W, Yang EJ, Ku SK, Song KS, Bae JS. Anti-inflammatory effects of oleanolic acid on LPS-induced inflammation in vitro and in vivo. Inflammation. 2013;36:94–102. doi: 10.1007/s10753-012-9523-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malek AM, Alper SL, Izumo S. Hemodynamic shear stress and its role in atherosclerosis. Jama. 1999;282:2035–2042. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.21.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mamot C, Drummond DC, Noble CO, Kallab V, Guo Z, Hong K, Kirpotin DB, Park JW. Epidermal growth factor receptor-targeted immunoliposomes significantly enhance the efficacy of multiple anticancer drugs in vivo. J. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11631–11638. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCarty OJ, Mousa SA, Bray PF, Konstantopoulos K. Immobilized platelets support human colon carcinoma cell tethering, rolling, and firm adhesion under dynamic flow conditions. Blood. 2000;96:1789–1797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mlinar LB, Chung EJ, Wonder EA, Tirrell M. Active targeting of early and mid-stage atherosclerotic plaques using self-assembled peptide amphiphile micelles. Biomaterials. 2014;35:8678–8686. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moore KJ, Sheedy FJ, Fisher EA. Macrophages in atherosclerosis: a dynamic balance. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013;13:709. doi: 10.1038/nri3520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Namiki M, Kawashima S, Yamashita T, Ozaki M, Hirase T, Ishida T, Inoue N, Hirata KI, Matsukawa A, Morishita R, Kaneda Y. Local overexpression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 at vessel wall induces infiltration of macrophages and formation of atherosclerotic lesion: synergism with hypercholesterolemia. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2002;22:115–120. doi: 10.1161/hq0102.102278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohsawa T, Miura H, Harada K. Improvement of encapsulation efficiency of water-soluble drugs in liposomes formed by the freeze-thawing method. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1985;33:3945–3952. doi: 10.1248/cpb.33.3945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pagano RE, Weinstein JN. Interactions of liposomes with mammalian cells. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Bioeng. 1978;7:435–468. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.07.060178.002251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pan H, Myerson JW, Hu L, Marsh JN, Hou K, Scott MJ, Allen JS, Hu G, San Roman S, Lanza GM, Schreiber RD. Programmable nanoparticle functionalization for in vivo targeting. FASEB J. 2013;27:255–264. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-218081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rubio-Guerra AF, Vargas-Robles H, Serrano AM, Vargas-Ayala G, Rodriguez-Lopez L, Escalante-Acosta BA. Correlation between the levels of circulating adhesion molecules and atherosclerosis in hypertensive type-2 diabetic patients. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 2010;32:308–310. doi: 10.3109/10641960903443533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shirure VS, Reynolds NM, Burdick MM. Mac-2 binding protein is a novel E-selectin ligand expressed by breast cancer cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e44529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suk JS, Xu Q, Kim N, Hanes J, Ensign LM. PEGylation as a strategy for improving nanoparticle-based drug and gene delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016;99:28–51. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun T, Simmons R, Huo D, Pang B, Zhao X, Kim CW, Jo H, Xia Y. Targeted delivery of Anti-miR-712 by VCAM1-Binding Au Nanospheres for Atherosclerosis Therapy. ChemNanoMat. 2016;2:400–406. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tan J, Thomas A, Liu Y. Influence of red blood cells on nanoparticle targeted delivery in microcirculation. Soft Matter. 2012;8:1934–1946. doi: 10.1039/C2SM06391C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Winter PM, Neubauer AM, Caruthers SD, Harris TD, Robertson JD, Williams TA, Schmieder AH, Hu G, Allen JS, Lacy EK, Zhang H. Endothelial ανβ3 integrin-targeted fumagillin nanoparticles inhibit angiogenesis in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006;26:2103–2109. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000235724.11299.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoo SP, Pineda F, Barrett JC, Poon C, Tirrell M, Chung EJ. Gadolinium-functionalized peptide amphiphile micelles for multimodal imaging of atherosclerotic lesions. ACS Omega. 2016;1:996–1003. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.6b00210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoon HJ, Moon ME, Park HS, Im SY, Kim YH. Chitosan oligosaccharide (COS) inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory effects in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;358:954–959. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu L, Li M, Wei L, Liu X, Yin J, Gao Y. Fast fixing and comprehensive identification to help improve real-time ligands discovery based on formaldehyde crosslinking, immunoprecipitation and SDS-PAGE separation. Proteome Sci. 2014;12:6. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-12-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]