Abstract

Carpobrotus edulis (Aizoaceae) is a fleshy creeper, native to South Africa and commonly found growing on coastal seashores. Recently this plant has been observed dying in large patches in areas close to Cape Town. Symptoms include a wilting of the leaves associated with death of the woody stems. The aim of this study was to identify the probable cause of this disease. Dead and dying stem tissues were found to be colonised by a species of Cytospora. Isolates of this fungus were identified based on DNA sequence data from the rDNA-ITS, translation elongation factor 1-α, β-tubulin and large subunit rDNA loci. Analyses of the data showed that the fungus is a new species of Cytospora, described here as Cytospora carpobroti sp. nov. Pathogenicity tests showed that C. carpobroti resulted in distinct lesions on inoculated stems but not the fleshy leaves. The origin of C. carpobroti is unknown and there is concern that it could be an introduced pathogen threatening the health of this important native plant.

Keywords: biodiversity, multi-gene phylogeny, one new taxon, pathogenicity, systematics

INTRODUCTION

Carpobrotus edulis (Aizoaceae), commonly known as sour fig, is an indigenous succulent species in South Africa. It occurs as a creeper growing along the east coast of the country and has been moved to many parts of the world where it is a popular garden plant. Ecologically, it plays an important role in binding sands in coastal areas (Wisura & Glen 1993, Chiban et al. 2011). Carpobrotus edulis is also used in traditional medicine because it contains antimicrobial compounds and its fruits are edible (Rood 1994, van der Watt & Pretorius 2001, Springfield et al. 2003).

Little is known regarding the diseases of C. edulis. It was believed to be free of pathogens when it was imported into California from South Africa for stabilising soil in the early 1900’s (McDonald et al. 1984). However, in 1980 many C. edulis plants were reported dying in southern California and McDonald et al. (1984) confirmed Pythium aphanidermatum, Phytophthora cryptogea and Verticillium dahlia causing the disease in that area. Other fungal pathogens identified on C. edulis include Albugo trianthemae causing white rust in New Zealand (McKenzie & Johnston 1999) and Anthostomella spartii on dead stems of C. edulis in Portugal (Francis 1975). There is only one reported endophyte, a Coniothyrium sp. known from this plant on La Gomera, one of the Canary Islands (Kock et al. 2007).

The genus Cytospora (Diaporthales, Cytosporaceae) includes fungal species that occur mostly on woody plants including angiosperms and gymnosperms. Species of Cytospora (sexual morphs: Leucostoma, Valsa, Valsella and Valseutypella) have a cosmopolitan distribution and are frequent endophytes in healthy plant tissues. They can also be important pathogens when their hosts are subjected to stress (Schoeneweiss 1981, 1983). In this pathogenic phase, most Cytospora species cause canker and die-back diseases (Sinclair et al. 1987, Farr et al. 1989). The conidiomata of these fungi are then found on the dying wood associated with these tissues.

Many Cytospora species are known to cause plant diseases; some of these are quite host specific while others have broad host ranges. For example, C. chrysosperma has been recorded on more than 80 plant hosts (Farr & Rossman 2016), while C. eucalypticola is a well-known pathogen specifically on Eucalyptus (Adams et al. 2005). Although the most aggressive Cytospora spp. occur on angiosperms, there are exceptions such as C. kunzei (= Valsa kunzei), which is a pathogen of Pinus elderica in plantations (Kavak 2005).

The aim of this study was to identify the Cytospora sp. closely associated with the death of C. edulis in various areas of the Cape Peninsula of South Africa. In addition, pathogenicity tests were conducted to assess the possible role of the fungus in causing disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Collection of samples and isolations

Samples of dying plants (Fig. 1) were collected at various sites along the Cape Peninsula, in the Western Cape Province of South Africa, in August 2016. The diseased stems were placed in paper bags and transferred to the laboratory for further study. Symptomatic tissues were examined under a dissection microscope where it was possible to observe conidiomata typical of a Cytospora sp. The conidial masses were exposed by removing the apices of the conidiomata with a sharp scalpel blade. Spore masses were removed from these structures with a sterile needle, and conidia were spread onto the surface of malt extract agar (MEA: 2 % Biolab malt extract, 2 % Difco agar) supplemented with streptomycin (400 mg/L). Specimens from this study were lodged in South African National Collection of Fungi (PREM), Roodeplaat, Pretoria, South Africa. Living cultures were preserved in the collection (CMW) of the Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, and the live culture collection (PPRI) of the South African National Collection of Fungi, Roodeplaat, Pretoria, South Africa.

Fig. 1.

A. Carpobrotus edulis plants. B. Dying C. edulis.

DNA extraction, sequencing and phylogenetic analyses

DNA was extracted using the PrepMan® Ultra kit (Applied Biosystems) from mycelium of 5-d-old axenic cultures. DNA sequences were generated for the internal transcribed spacer region of the ribosomal RNA (rRNA) operon amplified with primers ITS-1F (Gardes & Bruns 1993) and ITS-4 (White et al. 1990), the translation elongation factor 1-α (TEF1-α) gene amplified with primers EF1-728F and EF1-986R (Carbone & Kohn 1999), the β-tubulin (TUB2) gene amplified with primers BT2a and BT2b (Glass & Donaldson 1995) and large ribosomal subunit (LSU) gene region amplified with primers LR0R and LR5F (Vilgalys & Hester 1990).

The 25 μL PCR reaction mixtures contained 1 μL DNA, 17.7 μL molecular distilled water, 0.3 μL MyTaq DNA Polymerase, 5 μL MyTaq Buffer (MgCl2, dNTPs), 0.5 μL of each primer. The amplification conditions were as follows; initial denaturation of 5 min at 95 °C, followed by 25 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 55 °C for ITS and LSU, 53 °C for TEF1-α and 54 °C for TUB2, and 1 min at 72 °C, and a final extension of 7 min at 72 °C. The PCR amplicons were visualized separately on a 1 % agarose gel with GelRed™. The conditions for the PCR sequencing were the same as those described by Begoude et al. (2010).

The sequences were compared with our unpublished sequence dataset for the phylogenetic analyses. The datasets were aligned online using MAFFT v. 7.0 (https://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/) (Katoh et al. (2017) and checked manually for alignment errors. The phylogenetic analyses for all the datasets were performed using Maximum Likelihood (ML). The best nucleotide substitution models for each dataset were found separately with jModelTest v. 3.7 (Posada & Buckley 2004). The model for GTR was chosen for the combined datasets of ITS, TEF1-α, TUB2 and LSU. The ML analyses were performed in PAUP v. 4.0b10 with the heuristic search option with 100 random additions of taxa, tree bisection and reconstruction (TBR) branch swapping and 1000 bootstrap replications in PAUP. The consensus trees were constructed in MEGA v. 7 and posterior probabilities were assigned to branches after a 60 % majority rule.

Morphological characteristics

Purified cultures were incubated on 2 % MEA, at 25 °C for 2 wk after which fruiting structures began to develop on MEA. Fungal structures from both naturally infected tissue and culture were mounted on slides in sterile water that was later replaced with 85 % lactic acid and all the measurements and images were captured using these specimens. Up to fifty measurements were made for conidia and other morphologically characteristic structures where these were available. Naturally infected tissues bearing fungal structures were cut into small pieces and boiled for 1 min. The saturated pieces were mounted in Tissue Freezing Medium® (Leica, Germany) and cut into sections (12–16 μm thick) using a Leica Cryo-microtome (Leica, Germany). The sections were mounted on microscope slides in 85 % lactic acid for further observation. Observations were made using Nikon Eclipse Ni compound and SMZ18 dissection microscopes (Nikon, Japan). Images were captured with a Nikon DS-Ri camera and with the imaging software NIS-Elements BR, and all the measurements were also captured with this software.

Pathogenicity trials

Two inoculation techniques were used in this study. In one trial, the fleshy leaves of C. edulis were inoculated and in a second trial, inoculations were made on the woody stem tissues. In each case, 20 plants were inoculated with one of two isolates (CMW 48981 and CMW 48983) of the Cytospora sp. isolated from dying plants. An additional 20 plants were inoculated as controls with sterile toothpicks or uncolonised agar plugs.

The inoculum for the leaf inoculations was in the form of sterile tooth picks that had been placed on the surface of MEA for colonisation by the fungal isolate. The inoculated plates were incubated at 24 °C for 2 wk to ensure that the Cytospora sp. had fully penetrated the tooth picks. The colonized as well as the sterile tooth picks as control were then inserted firmly into the fleshy leaves of C. edulis plants grown in a greenhouse. These plants were observed for the appearance of symptoms for 6 wk.

For stem inoculations, the two Cytospora isolates were allowed to grow on MEA for 5 d at 24 °C. Discs (5 mm diam) of agar were cut from the actively growing margins of the cultures and these were placed into wounds of the same size on the C. edulis stems. In the case of the controls, inoculations were made with sterile MEA discs. The inoculated stems were sealed with parafilm to reduce desiccation and the chance of contamination. These plants were maintained in a greenhouse at 24 °C under natural light conditions and observed for the appearance of symptoms for 6 wk. Following this period, the trial was terminated, lesion sizes were measured and re-isolations were made on MEA. The variation in lesion length was analysed using Kruskal-Wallis Rank Sum test in R v. 3.4.3. A representative set of isolates were identified based on morphological characters in order to ensure that the isolated fungi were the same as those that had been inoculated into the plants.

RESULTS

Isolates, sequencing and phylogenetic analyses

Five isolates were obtained from symptomatic tissues and these were all included in the DNA sequence analyses (Table 1). The sequence datasets for the ITS, TEF1-α, TUB2 and LSU regions were analysed individually and in combination. The ITS sequence dataset contained 515, the TEF1-α dataset 361, the TUB2 dataset 545, the LSU dataset 482 and the combined dataset 1903 characters (TreeBASE Accession No. 22682).

Table 1.

The Cytospora carpobroti isolates from Carpobrotus edulis of this study used in the phylogenetic analyses. Type isolate is indicated in bold.

| Isolate No. | Identity | Location | Collector |

GenBank |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | TEF1-α | TUB2 | LSU | ||||

| CMW 48981 | Cytospora carpobroti | Cape Town, South Africa | M.J. Wingfield | MH382812 | MH411212 | MH411207 | MH411216 |

| CMW 48982 | Cytospora carpobroti | Cape Town, South Africa | M.J. Wingfield | MH382813 | MH411213 | MH411208 | - |

| CMW 48983 | Cytospora carpobroti | Cape Town, South Africa | M.J. Wingfield | MH382814 | - | MH411209 | MH411217 |

| CMW 48984 | Cytospora carpobroti | Cape Town, South Africa | M.J. Wingfield | MH382815 | MH411214 | MH411210 | MH411218 |

| CMW 48985 | Cytospora carpobroti | Cape Town, South Africa | M.J. Wingfield | MH382816 | MH411215 | MH411211 | MH411219 |

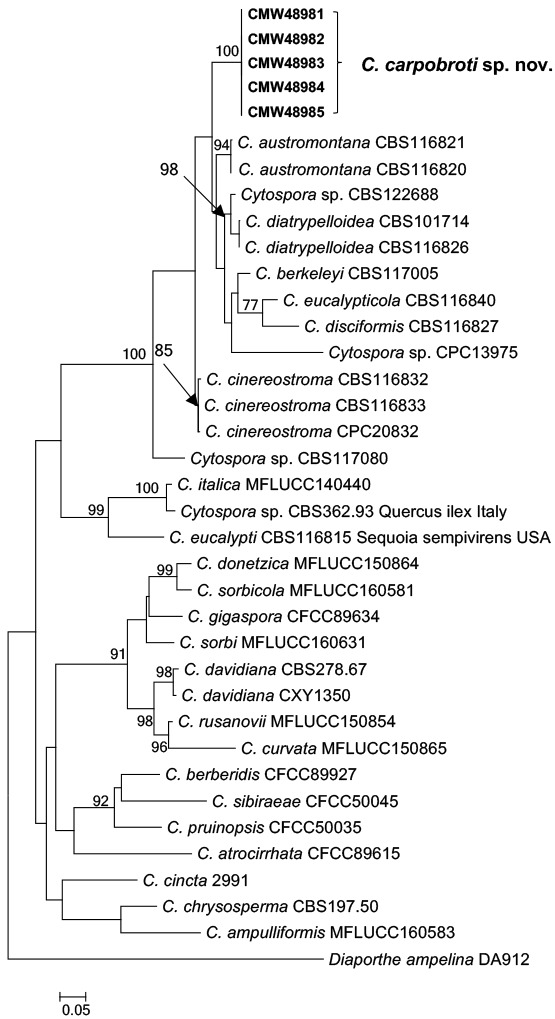

A distinct clade, which clustered as sister to Cytospora austromontana was revealed in all the analyses (Fig. 2). These isolates differed from C. austromontana by unique fixed alleles in ITS (7 bp), TEF1-α (35 bp), TUB2 (29 bp) and LSU (7 bp). The topology of the trees obtained from the ML analyses were similar for all loci as well as in the combined analyses.

Fig. 2.

Maximum Likelihood (ML) tree of the combined data set of ITS r-DNA, β-tubulin, TEF1-α and LSU loci sequences. Bootstrap values above 70 % are given at the nodes. The tree was rooted to Diaporthe ampelina. Isolates of this study are indicated as bold.

Morphological characteristics

The isolates in the unknown fungus had pale grey colonies with moderate aerial mycelium. The cultures produced conidiomata with yellow oozing conidia and hyaline allantoid conidia after approximately 10 d.

Taxonomy

A new species in the Cytosporaceae (= Valsaceae) is described here for the isolates from Carpobrotus edulis that reside in a unique clade amongst other species of Cytospora. No sexual morph was found on the host or in culture, and the description is based on morphological characteristics of the asexual morph only.

Cytospora carpobroti Jami, Marinc. & M.J. Wingf., sp. nov. MycoBank MB825251. Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Micrographs of Cytospora carpobroti sp. nov. (holotype PREM 62170, ex-holotype CMW 48981 = PPRI 29136). A. Symptomatic stem. B. Vertical section of conidiomata immersed in stem. C. Close-up of conidiomatal wall showing conidiophores lining along the locule. D. Conidiomata formed on toothpick in 2 % MEA. E. Vertical section of conidiomata in vitro. F, G. Conidiophores and conidiogenous cells. H. Conidia. I. Culture morphology of 5 d and 50 d old on 2 % MEA in the dark (reverse in lower half). Scale bars: A = 1 mm; B, E = 100 μm; C = 50 μm; D = 250 μm; F–H = 5 μm.

Etymology: Name refers to the host genus Carpobrotus.

Conidiostromata in vivo subepidermal, immersed, subglobose to ellipsoidal, uni- or multiloculate, convoluted, 150–330 μm long, 130–315 μm wide, with ostiolar neck reaching the surface of the substrate. Stromatic tissue eustromatic, textura angularis. Conidiomatal walls composed of 4–6 layers of thick-walled, moderately compressed, pigmented cells, 10.5–27 μm thick. Conidiomata in vitro on toothpick in 2 % MEA, stromata 0.3–0.4 mm diam, multilocular, subdivided by invaginations, giving rise to up to 5 elongated black necks, with obtusely rounded apex, exuding a yellow conidial cirrhus or globoid conidial mass. Conidiophores borne along the locules, hyaline, smooth, branched, aseptate, 8.5–11 × 2.5–3.5 μm, embedded in a gelatinous layer. Conidiogenous cells phialidic, sub-cylindrical, tapering towards apices, collarettes minute, 4.5–12 × 1–2 μm; arranged in rosettes. Conidia hyaline, smooth, guttulate, allantoid, apex sub-obtusely rounded, aseptate, 3.5–6 × 1 μm (avg. 5.0 × 1 μm).

Culture characteristics: Colony on 2 % MEA showing optimum growth at 25 °C, reaching 69.2 mm in dark in 5 d, followed by at 30 °C reaching 55.6 mm and at 20 °C reaching 50.7 mm, no growth at 35 °C, showing circular growth with smooth margin, mycelium mostly aerial, flat and fluffy, at lower temperature mycelium mostly submerged, above and reverse olivaceous buff with inner circle greenish olivaceous.

Host: Carpobrotus edulis.

Distribution: Cape Town, South Africa.

Specimen examined: South Africa, Western Cape Province, Cape Town, Carpobrotus edulis, Aug. 2016, M.J. Wingfield (holotype PREM 62170, culture ex-type CMW 48981 = PPRI 29136).

Additional materials examined: Isolates CMW 48982 = PPRI 29137, CMW 48983 = PPRI 29138, CMW 48985.

Note: Cytospora carpobroti is morphologically similar to C. austromontana except for the dimensions of the conidiogenous cells of C. austromontana (7–12 × 1.5), which are larger than those of C. carpobroti.

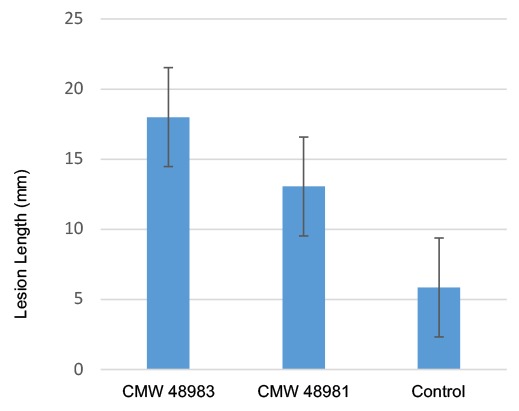

Pathogenicity trials

The two isolates of C. carpobroti produced lesions in the cambium of inoculated C. edulis stems within 6 wk. In contrast, there was no lesion development in the inoculated fleshy leaves or in any of the control inoculations (Fig. 4). Statistical analyses showed that lesion size (Fig. 5) for the new species were significant (P-value < 0.05). Cytospora carpobroti was consistently re-isolated from lesions. The fungus was never re-isolated from the control inoculations.

Fig. 4.

Inoculations of Carpobrotus edulis stem and leaf tissue with Cytospora carpobroti sp. nov. after six weeks. A, B. Stems inoculated with isolates CMW 48983 and CMW 48981 respectively showing distinct lesion development. C. Leaf inoculated with isolate CMW 48983 with no lesion development. D. Control inoculation on stem showing absence of lesion. Scale bar = 5 mm.

Fig. 5.

Mean lesion length (mm) for isolates of Cytospora carpobroti 6 wk after inoculation on Carpobrotus edulis.

DISCUSSION

This study reports a new disease of C. edulis occurring in South Africa. The fungus isolated from diseased plants was found to represent a new species of Cytospora for which the name C. carpobroti is here established. Pathogenicity tests with two isolates of C. carpobroti showed that the fungus was able to cause disease on inoculated stems of C. edulis. Interestingly, inoculations on the fleshy leaves of plants failed to induce lesions.

Cytospora spp. commonly have wide host ranges (Adams et al. 2005) and occur mostly on woody plants. It was consequently interesting to encounter a disease caused by a Cytospora sp. on a succulent plant in this study. However, the stems of C. edulis are woody and the fact that pathogenicity tests were positive only on the woody stems is consistent with the known biology of Cytospora spp.

Based on phylogenetic analyses, the newly described C. carpobroti resides in a sister clade with C. austromontana. Cytospora carpobroti is morphologically similar to C. austromontana other than in the dimensions of conidiogenous cells. Cytospora austromontana was first isolated from a cankered branch of Eucalyptus pauciflora in Australia (Adams et al. 2005) and it was remarkable to find a closely related species from a very different ecological niche in the present study.

Relatively few studies have been conducted on the pathogenicity of Cytospora species. Generally, these fungi are considered endophytes and opportunistic or weak secondary pathogens (Adams et al. 2005). Some species such as C. mali are well-known pathogens on pear and apple trees, which are able to induce canker formation in pathogenicity tests (Ke et al. 2013). Although C. carpobroti was able to cause lesions on inoculated plants in this study, it is possible that these plants were subjected to some stress factor and that the fungus was acting as an opportunistic pathogen. This would be consistent with the biology of most Cytospora spp. causing plant diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Prof. Brenda Wingfield for assistance in collecting samples and Dr Trudy Paap for reviewing a draft version of the manuscript. Members of the Tree Protection Cooperative Programme (TPCP), the DST/NRF Centre of Excellence in Tree Health Biotechnology (CTHB) and the University of Pretoria, South Africa, are acknowledged for financial support.

REFERENCES

- Adams GC, Wingfield MJ, Common R, et al. (2005). Phylogenetic relationships and morphology of Cytospora species and related teleomorphs (Ascomycota, Diaporthales, Valsaceae) from Eucalyptus. Studies in Mycology 52: 1–142. [Google Scholar]

- Begoude BAD, Slippers B, Wingfield MJ, et al. (2010). Botryosphaeriaceae associated with Terminalia catappa in Cameroon, South Africa and Madagascar. Mycological Progress 9: 101–123. [Google Scholar]

- Carbone I, Kohn LM. (1999). A method for designing primer sets for speciation studies in filamentous ascomycetes. Mycologia 91: 553–556. [Google Scholar]

- Chiban M, Soudani A, Sinan F, et al. (2011). Single, binary and multi-component adsorption of some anions and heavy metals on environmentally friendly Carpobrotus edulis plant. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 82: 267–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farr DF, Bills GF, Chamuris GP, et al. (1989). Fungi on plants and plant products in the United States. APS Press, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Farr DF, Rossman AY. (2016). Fungal Databases, Systematic Mycology and Microbiology Laboratory, ARS, USDA. http://nt.ars-grin.gov/fungaldatabases/. [Google Scholar]

- Francis SM. (1975). Anthostomella Sacc. (part. I). Commonwealth Mycological Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Gardes M, Bruns TD. (1993). ITS primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Molecular Ecology 2: 113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass NL, Donaldson GC. (1995). Development of primer sets designed for use with the PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous ascomycetes. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 61: 1323–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Rozewicki J, Yamada KD. (2017). MAFFT online service: multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Briefings in Bioinformatics. 10.1093/bib/bbx108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavak H. (2005). Cytospora kunzei on plantation-grown Pinus elderica in Turkey. Australasian Plant Pathology 34: 151–156. [Google Scholar]

- Ke X, Huang L, Han Q, et al. (2013). Histological and cytological investigations of the infection and colonization of apple bark by Valsa mali var. mali. Australasian Plant Pathology 42: 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kock I, Krohn K, Egold H, et al. (2007). New massarilactones, Massarigenin E, and coniothyrenol, isolated from the endophytic fungus Coniothyrium sp. from Carpobrotus edulis. European Journal of Organic Chemistry 2007: 2186–2190. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald J, Hartman J, Shapiro J. (1984). Pathogens of ice plant in California. Plant Disease 68: 965–967. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie E, Johnston P. (1999). New records of phytopathogenic fungi in the Chatham Islands, New Zealand. Australasian Plant Pathology 28: 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Posada D, Buckley TR. (2004). Model selection and model averaging in phylogenetics: advantages of Akaike information criterion and Bayesian approaches over likelihood ratio tests. Systematic Biology 53: 793–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rood B. (1994). From the veld pharmacy. Cape Town, Tafelberg Publishers Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Schoeneweiss DF. (1981). The Role of Environmental Stress in Diseases of Woody Plants. Plant Disease 65: 308–314. [Google Scholar]

- Schoeneweiss DF. (1983). Drought predisposition to Cytospora canker in blue spruce. Plant Disease 67: 383–385. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair WA, Lyon HH, Johnson WT. (1987). Diseases of Trees and Shrubs. Coinstock Publishing Associates, Cornell University Press, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Springfield E, Amabeoku G, Weitz F, et al. (2003). An assessment of two Carpobrotus species extracts as potential antimicrobial agents. Phytomedicine 10: 434–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Watt E, Pretorius JC. (2001). Purification and identification of active antibacterial components in Carpobrotus edulis L. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 76: 87–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilgalys R, Hester M. (1990). Rapid genetic identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. Journal of Bacteriology 172: 4238–4246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, et al. (1990). Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis MA, Gelfaud DH, Sninsky JJ, White TJ, eds. PCR protocols. A guide to methods and applications. San Diego, CA, USA: Academic Press, 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Wisura W, Glen H. (1993). The South African species of Carpobrotus (Mesembryanthema: Aizoaceae). Contributions to the Bolus Herbarium 15: 76–107. [Google Scholar]