Abstract

Background

Treatment failures in cancers, including multiple myeloma (MM), are most likely due to the persistence of a minor population of tumor-initiating cells (TICs), which are noncycling or slowly cycling and very drug resistant.

Methods

Gene expression profiling and real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction were employed to define genes differentially expressed between the side-population cells, which contain the TICs, and the main population of MM cells derived from 11 MM patient samples. Self-renewal potential was analyzed by clonogenicity and drug resistance of CD24+ MM cells. Flow cytometry (n = 60) and immunofluorescence (n = 66) were applied on MM patient samples to determine CD24 expression. Therapeutic effects of CD24 antibodies were tested in xenograft MM mouse models containing three to six mice per group.

Results

CD24 was highly expressed in the side-population cells, and CD24+ MM cells exhibited high expression of induced pluripotent or embryonic stem cell genes. CD24+ MM cells showed increased clonogenicity, drug resistance, and tumorigenicity. Only 10 CD24+ MM cells were required to develop plasmacytomas in mice (n = three of five mice after 27 days). The frequency of CD24+ MM cells was highly variable in primary MM samples, but the average of CD24+ MM cells was 8.3% after chemotherapy and in complete-remission MM samples with persistent minimal residual disease compared with 1.0% CD24+ MM cells in newly diagnosed MM samples (n = 26). MM patients with a high initial percentage of CD24+ MM cells had inferior progression-free survival (hazard ratio [HR] = 3.81, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 5.66 to 18.34, P < .001) and overall survival (HR = 3.87, 95% CI = 16.61 to 34.39, P = .002). A CD24 antibody inhibited MM cell growth and prevented tumor progression in vivo.

Conclusion

Our studies demonstrate that CD24+ MM cells maintain the TIC features of self-renewal and drug resistance and provide a target for myeloma therapy.

The cancer stem cell theory recognizes a rare population of cells distinct from bulk tumor cells with the ability to initiate and propagate tumors. This very limited population is further distinguished by pluripotency, self-renewal capacity, and resistance to chemotherapy and radiotherapy. These tumor-initiating cells (TICs), also known as cancer stem cells, give rise to differentiated progeny leading to heterogeneity of tumors, whereby differentiated cancer cells can dedifferentiate to TICs. TICs were originally documented and described in acute myeloid leukemia (1,2) and, in the past 20 years, have been identified in a growing number both of hematologic and solid tumors (3–6).

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a plasma cell malignancy defined by bone, renal, immunological, and hematological complications. Although autologous stem cell transplantation in combination with novel drug regimens has greatly improved patient outcomes, the majority of MM patients die of their disease after relapse. The high frequency of relapse suggests the persistence of a treatment-resistant population (7,8). Furthermore, normal polyclonal plasma cells actively secrete intact immunoglobulins both with κ and λ light chains (9,10), and MM is characterized by an excess of clonotypic plasma cells that express either κ or λ light chains (11), supporting a clonal origin of MM tumor cells.

Still, identifying a consensus TIC phenotype has remained elusive in MM. MM side-population (SP) cells, which are considered a functional surrogate marker for cancer stem cells, generate more colonies compared with mature MM cells and may lack CD138 expression (12,13). Possible stem cell populations include light-chain (LC)- restricted cells with a CD138–/CD19+/CD27+ phenotype (8,14,15), CD138+/CD34+/B7–H1+ subpopulations (16), and CD38++/CD45– plasma cells (17–19).

The human cell surface antigen CD24 is a sialoglycoprotein localized in membrane lipid raft domains (20). As a heat-stable antigen, CD24 has been used as a marker to identify hematopoietic cells, neuronal cells, and B lymphocytes (21,22). Previous studies have found that CD24 is a TIC marker in multiple cancers, including liver, ovarian, and pancreatic (23–26).

Because of the persistence of clonal plasma cells for more than 10 years in MM patients in complete remission (CR) with minimal residual disease (MRD) (27), we hypothesized that at least some of the MM cells in these patients had TIC features. Here, we performed a systematic analysis to identify and characterize this rare TIC population using primary MM samples and MM cell lines.

Methods

Patient Samples

Deidentified clinical bone marrow (BM) aspirates were obtained from 137 MM patients at the University of Iowa and the Nanjing Medical University. Studies were approved by the institutional review boards at each institution. Written informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Gene Expression Profiling

Gene expression profiling was performed as previously described (28–30). GEO accession numbers are GSE109650 and GSE109651.

Flow Cytometry Analysis of Primary MM Samples

Flow cytometric analysis was carried out on 60 fresh BM specimens. BM cells were stained with a multicolor combination of fluorescent monoclonal antibodies: CD38-APC, CD138-FITC, CD56-APCA750, CD19-PC5.5, and CD24-PE (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence (IF) analysis was performed on 66 newly diagnosed MM samples. Immunoreactivity of CD24 expression was evaluated in the CD138-positive plasma cells by double staining with CD24- and CD138-specific antibodies. The overlap coefficient (OC) represents the quantitative colocalization of double-positive CD24 and CD138 MM cells (31).

Mouse Studies

Male and female NOD.Cγ-Rag1 mice age 6–8 weeks (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were used. Xenograft MM mice were established by subcutaneous and intravenous injection of cells of the human ARP1 MM cell line. MM mice were treated with or without the CD24 antibody, SWA11, and bortezomib (BTZ). The animal studies were performed according to the guidelines of the institutional animal care and local veterinary office and ethics committee of the University of Iowa. Three mice per group for subcutaneous and five or six mice per group for intravenous injection were included. The control and treatment groups were matched by sex and age.

Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as average (SD), as indicated in the figure legends. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 7.0.

One-way analysis of variance was used to determine the statistically significant difference for multiple group comparisons. For two-group comparisons, the unpaired, two-sided, independent Student t test was applied to analyze these data unless otherwise described in the figure legends. Mouse survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and log-rank statistics were used to test for their equality across groups. To investigate the prognostic value of CD24 expression in MM patients, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and multivariable Cox proportional hazards analysis were performed. The proportional hazards assumption was confirmed by the examination of log (–log [survival]) curves. Statistical significance was set at P less than .05 and all statistical tests were two-sided.

Additional methods can be found in Supplementary Methods (available online).

Results

Identification of TIC Phenotypic Marker(s) in Primary Myeloma Samples

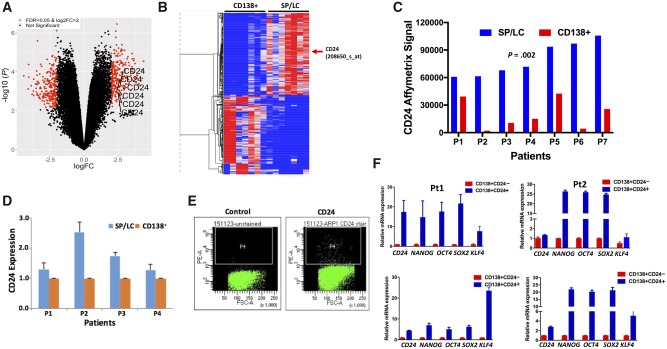

We isolated the LC- restricted SP (LC/SP) MM cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting from seven primary MM samples. Affymetrix microarrays were performed on seven-paired LC/SP and the bulk MM cells (CD138+) on these 14 samples. There were 176 upregulated genes (263 probes) and 155 downregulated genes (251 probes) with a more than fourfold change (logFC > 2) and a false discovery rate of less than .05 when comparing SP/LC with paired CD138+ samples (Figure 1, A and B). We were particularly interested in genes encoding cell surface proteins and found that IL8A, TNFRSF10C, CD24, and CEACAM1 genes were the top upregulated genes in the LC/SP MM cells compared with bulk MM cells (CD24: 79 792 [18 547] vs 19 979 [16 300], P = .002; Figure 1C). Increased CD24 expression was confirmed in LC/SP MM cells by real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) (Figure 1D). Using flow cytometry with antibodies against IL8A, TNFRSF10C, CD24, and CEACAM1 in multiple MM cell lines (data not shown), only CD24 identified a distinct rare population (0.4–3.1%; Figure 1E). We further examined gene expression in CD24+ MM cells separated from multiple MM cell lines. The expression of induced pluripotent or embryonic stem cell (iPS/ES) genes, such as OCT4 (also known as POU5F1), NANOG, and SOX2, was statistically significantly upregulated in CD24+ MM cells compared with CD24– MM cells (more than eightfold, P < .001) (Supplementary Figure 1; Supplementary Table 1, available online). Four primary MM samples were separated into CD138+CD24+ and CD138+CD24– MM cells. Consistent with the MM cell line data, the expression of iPS/ES genes was also increased in primary CD138+CD24+ MM cells compared with CD138+CD24– MM cells (Figure 1F). Therefore, we focused on studying CD24 as a putative MM TIC marker.

Figure 1.

Identification of CD24 as a tumor-initiating cell marker in multiple myeloma (MM). A) The volcano plot was used to visualize gene fold change (FC) and statistical significance between side-population (SP)/light-chain (LC) and CD138+ MM cells from seven paired primary MM samples (n = 14). We used linear models with a false discovery rate (FDR) of less than .05 and logFC greater than 2 as the cutoff for differential expressed genes analysis. B) The heatmap was generated by Morpheus. Normalized log2 expression Affymetrix Signals were subtracted from row mean and divided by row SD. The color of each cell in the tabular image represents the expression level of each gene, with red representing an expression greater than the mean, blue representing an expression less than the mean, and the deeper color intensity representing a greater magnitude of deviation from the mean. The red arrow indicates the CD24 gene. C) The CD24 Affymetrix Signal was presented from seven paired MM samples (n = 14) with SP/LC and CD138+ detected by gene expression profiles. The two-sided paired t test was used to calculate the P value. D) CD24 messenger RNA (mRNA) expression from four MM patients with paired SP/LC and CD138+ MM cells was detected by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). E) Dot plots by flow cytometry presented CD24+ MM cells in MM cell lines. The figure shows a representative ARP1 MM cell line. F) The qRT-PCR results showed the expression of induced pluripotent or embryonic stem cell genes (NANOG, OCT4, SOX2, and KLF4) between CD138+CD24+ and CD138+CD24– cells derived from four primary MM samples. The data are presented as the mean (SD) of triplicates. FSC-A = forward scatter area; PE-A = phycoerythrin area; Pt = patient.

Characterization of TIC Features of CD24+ Myeloma Cells in Vitro

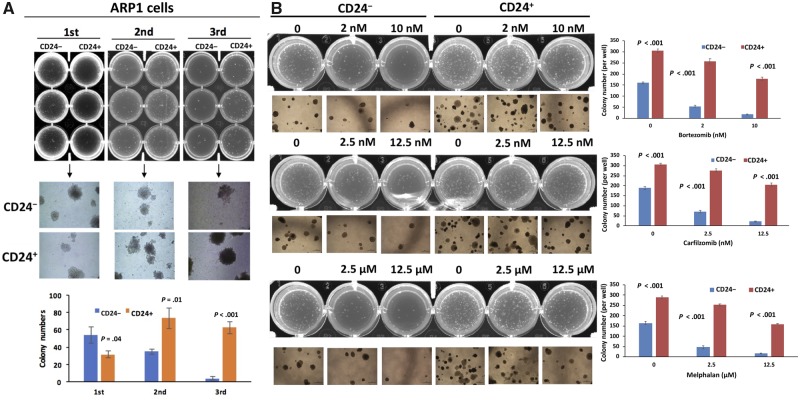

To examine self-renewal potential by clonogenicity, we isolated CD24+ and CD24– cells from ARP1 and OCI-MY5 MM cell lines and examined each subpopulation for colony formation capacity. CD24+ and CD24– colonies were serially replated in methylcellulose. Compared with CD24– MM cells, CD24+ ARP1 MM cells exhibited statistically significantly decreased clonogenic potential in the first passage, which is mainly a measure of cell proliferative capacity (mean difference= −22.33, 95% confidence interval [CI] = −42.44 to −2.23, P = .04; Figure 2A). However, the clonogenic potential was statistically significantly increased for the CD24+ MM cells in the second (mean difference = 38.67, 95% CI = 15.29 to 62.04, P = .01; Figure 2A) and third passages (mean difference: 58.33, 95% CI = 44.15 to 72.52, P < .001; Figure 2A), which are the real measures of the self-renewal capacity. This suggests that CD24+ MM cells possess the capacity for long-term self-renewal, a key feature of TICs. Similar results were observed with the OCI-MY5 cell line (Supplementary Figure 2, available online).

Figure 2.

Characterization of tumor-initiating cell features of CD24+ myeloma cells in vitro. A) CD24+ and CD24– cells from the ARP1 cell line were serially plated in methylcellulose in triplicate up to three passages. The colony quantification is shown at the bottom panel for each passage after 2 weeks. B) CD24+ and CD24– ARP1 cells from the second passage were plated for colony formation and treated with the indicated drugs and different doses. The colony quantification is shown in the right panels for each drug. The data are presented as the mean (SD) of triplicate samples. P values were calculated using two-sided Student t test.

To examine whether CD24+ MM cells showed higher resistance to chemotherapeutic drugs, another characteristic of TICs (32), the soft agar clonogenic formation assay was employed using multiple drugs. Second passage cells were tested. The ARP1 cells from the first passage were collected and replated in 12-well plates. CD24+ and CD24– ARP1 MM cells in the second passage were treated with BTZ (2 and 10 nM) or carfilzomib (2.5 and 12.5 nM) or melphalan (2.5 and 12.5 μM) for 2 weeks. As shown in Figure 2B, CD24+ ARP1 cells were statistically significantly more resistant to treatment (>2.5-fold, P < .001) than CD24– ARP1 cells. This was repeated in the OCI-MY5 MM cell line with similar results (Supplementary Figure 3, available online). To evaluate whether the CD24+ population was indeed enriched after chemotherapy, we treated the parental Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-8226 and drug-resistant RPMI-8226-R5 cells with BTZ in vitro for 72 hours. Flow cytometry analysis indicated that the CD24+ population was dramatically increased in the chemoresistant residual cells of both cell lines (Supplementary Figure 4, greater than twofold, available online).

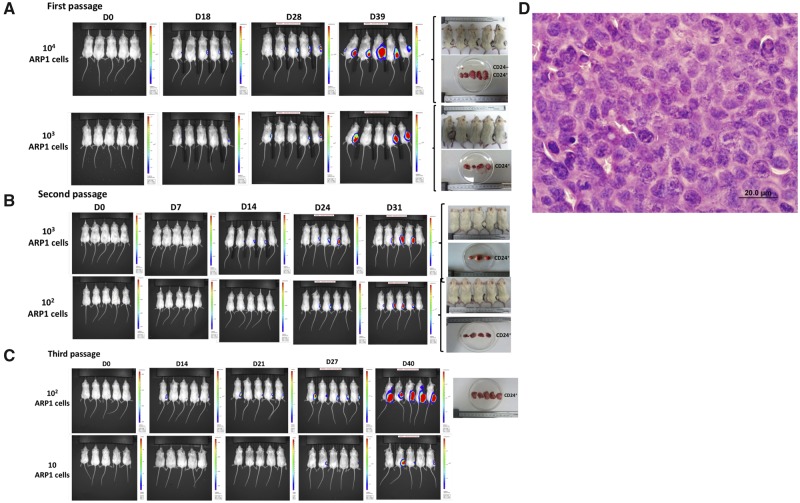

Determination of Tumorigenesis of CD24+ Myeloma Cells in Vivo

We then investigated the tumorigenic properties of CD24+ MM cells in mice. CD24+ and CD24– populations were separated from luciferase-labeled ARP1 and OCI-MY5 cell lines. CD24+ and CD24– MM cells were injected subcutaneously into the right and left flanks of NOD-Rag1null mice. Tumor development and growth were monitored weekly by bioluminescence. In the first generation, 10 000 CD24+ ARP1 cells formed tumors in five of five mice 39 days after injection, whereas 10 000 CD24– ARP1 cells resulted in only one tumor among five mice. With injection of 1000 cells per mouse, CD24+ ARP1 cells generated tumors in four of five mice, whereas no tumors were detected by injecting 1000 CD24– ARP1 cells (Figure 3A). To further assess the self-renewal capacity of CD24+ MM cells, serial transplantations were performed. Tumors were excised from the primary recipients, dissociated into a single-cell suspension, resorted into CD24+ and CD24– MM cells, and then reinjected into secondary and tertiary recipients. Both 1000 and 100 CD24+, but not CD24–, ARP1 cells were able to induce tumors in four of five mice 31 days after injection in the secondary recipients (Figure 3B, second passage). With the third transplantation, as few as 100 CD24+ MM cells gave rise to tumors in all five mice, and even with 10 CD24+ MM cells, tumors developed in three of five mice after 27 days (Figure 3C, third passage). The MM origin was confirmed by hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 3D). Similar results were observed with the OCI-MY5 cell line (Supplementary Figure 5, available online).

Figure 3.

Determination of tumorigenesis of CD24+ myeloma cells in vivo. A–C) CD24+ multiple myeloma (MM) cells developed tumors in NOD-Rag1null mice. The CD24+ (right flank) and CD24– (left flank) ARP1 cells were injected into NOD-Rag1null mice from the first through third generations. Representative IVIS imaging shows the tumor growth from the first, second, and third transplantations of ARP1 MM cells. Only 10 CD24+ MM cells were sufficient to generate tumors in three of five mice by day 27 (the third generation). D) Hemotoxylin and eosin staining of a tumor section from the indicated mouse (×60 magnification).

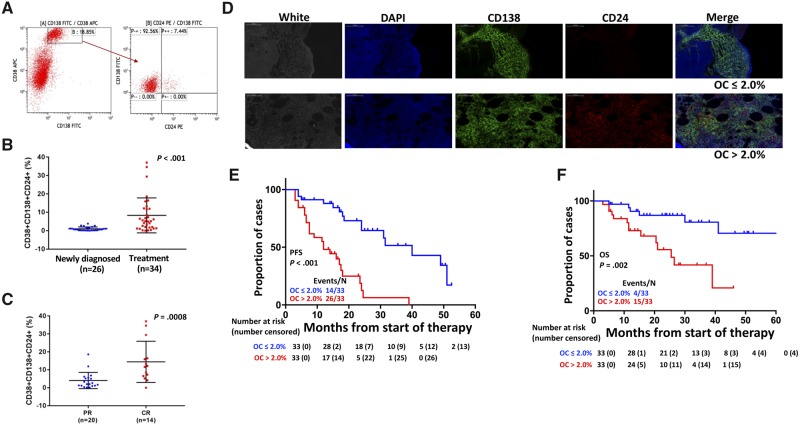

Clinical Relevance of CD24+ Myeloma Cells in Primary Patient Samples

To confirm the presence of the MM CD24+ subpopulation in primary MM patients, we performed flow cytometry analysis of CD24+ MM cells in 60 primary MM samples with different disease stages of MM. The CD138+/CD38+/CD56+/CD19– panel was used to determine clonotypic MM cells (33–36). As shown in Figure 4A, a subset of primary MM cells was CD24-positive in the CD138+CD38+ MM cells (the same population of CD138+/CD38+/CD56+/CD19– MM cells; Supplementary Table 2, available online) as detected by flow cytometry. Our data showed that the percentage of CD24+ MM cells was highly variable in primary MM samples. The mean percentage of CD138+CD38+CD24+ MM cells was 1.0% in the 26 newly diagnosed MM samples, whereas it was 8.3% in the 34 samples after treatment (1.0 [0.2]% vs 8.3 [1.6]%, 95% CI = 3.52% to 11.04%, P = .003) (Figure 4B). This percentage further increased in MM samples of patients in CR, but with MRD, compared with patients in partial remission (4.0 [1.0]% vs 14.4 [3.1]%, 95% CI = 4.66% to 16.14%, P = .008) (Figure 4C). In addition, a higher frequency of CD138+CD38+CD24+ cells was identified in more advanced disease (International Staging system [ISS] I and II vs ISS III) (3.7 [0.9]% vs 7.8 [2.4]%, 95% CI = −0.03% to 8.54%, P = .05) (Supplementary Figure 6A, available online) and in patients with more bone lytic lesions detected by X-ray (1.9 [0.5]% vs 7.8 [1.7]%, 95% CI = 2.07% to 9.86%, P = .003) (Supplementary Figure 6B, available online).

Figure 4.

Determination of the clinical relevance of CD24+ myeloma cells in primary patient samples. A) Flow cytometry shows a representative sample analyzed by CD138-, CD38-, and CD24-specific antibodies. B) The percentages of CD24+ multiple myeloma (MM) cells were compared in newly diagnosed MM patients and MM patients after treatment, with samples collected for evaluating response to bortezomib (BTZ)-based therapy immediately after two to three cycles of therapy. The two-sided t test was used to calculate the P value. C) The percentages of CD24+ MM cells were compared between partial remission (PR) and complete remission (CR) with minimal residual disease. The two-sided t test was used to calculate the P value. D) Double staining immunofluorescence of CD138 and CD24 in primary MM samples: Representative immunostaining showed the expression of CD138 (green) and CD24 (red) in primary human MM bone marrow (BM). DAPI was used for cell nuclear counterstains; scale bars represent 100 μm (black and white). E,F) Kaplan-Meier analyses showed progression-free survival (PFS; E) and overall survival (OS; F) of 66 newly diagnosed MM patients. Overlap coefficient (OC) scores were used to determine the degree of overlap of CD138 and CD24 fluorescence signals. The P values presented in this figure were based on the log-rank test. Each line represents different subgroups determined by the CD24 expression and described in the figure and color coded as indicated. The 60 samples for flow cytometry were freshly isolated from BM aspirates and included newly diagnosed and treated MM patients. These samples were collected for evaluating response to BTZ-based therapy immediately after two to three cycles of therapy, whereas the 66 samples used for immunofluorescence were stored BM biopsies embedded in paraffin blocks from newly diagnosed MM patients. The two sample sets were collected at different time points and did not overlap. APC = allophycocyanin; DAPI = 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; FITC = fluorescein isothiocyanate; PE = phycoerythrin.

We also analyzed CD24 protein expression in 66 newly diagnosed MM patients by double staining with human CD138 and CD24-specific antibodies using IF. CD24-positive percentages were obtained by counting 1000 CD138+ MM cells per sample. Quantitative colocalization analysis was performed to estimate the degree of overlap of fluorescence signals (31). MM samples were grouped as high-CD24 (OC score >2.0%) and low-CD24 (OC score ≤ 2.0%) expression in MM cells. Fifty percent (33 of 66) of MM patients showed 2.0% or less CD24+ MM cells, and another one-half had more than 2.0% CD24+ MM cells (up to 3.6%; data not shown) (Figure 4D). MM patients with the high-CD24 expression had an inferior progression-free survival (hazard ratio [HR] = 3.81, 95% CI = 5.66 to 18.34, P < .001; Figure 4E) and overall survival (HR = 3.87, 95% CI = 16.61 to 34.39; P = .002; Figure 4F). Interestingly, compared with higher CD24+ samples, patients with lower CD24+ MM cells also showed statistically significantly better responses to chemotherapy as evidenced by increased objective response rate (mean difference: 27.0%, 95% CI = 1.10% to 1.71%, P = .008) and very good or better partial remission (mean difference: 36.0%, 95% CI = 0.96% to 1.68%, P = .003). We did not observe a statistically significant relationship between percentage of CD24+ MM cells and CR (mean difference: 19.0%, 95% CI = 0.83% to 1.73%, P = .08) and stringent CR (sCR) or better (mean difference: 15.0%, 95% CI = 0.21% to 1.57%, P = .12). Consistent with the flow cytometry data, IF OC in more than 2.0% of MM patients showed increased advanced disease at ISS III (69.7% vs 45.5%, P = .05) and elevated β2-macroglobulin (β2M) (81.8% vs 57.6%, P = .03) and albumin (ALB) (57.6% vs 27.3%, P = .02) (Table 1). On multivariable Cox analyses, high CD24 expression detected by IF independently conferred both inferior progression-free survival (HR = 5.06, 95% CI = 1.84 to 13.00, P = .002; Supplementary Tables 3 and 4, available online) and overall survival (HR = 10.40, 95% CI = 2.26 to 47.83, P = .003; Supplementary Tables 5 and 6, available online).

Table 1.

Association between CD24 expression with clinical parameters in 66 MM patients

| Characteristics | Abnormal No. (%) n = 66 | OC ≤2% No. (%) n = 33 | OC >2% No. (%) n = 33 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≥65 y | 22 (33.3) | 8 (24.2) | 14 (42.4) | .19* |

| Male | 35 (53.0) | 14 (42.4) | 21 (63.6) | .08† |

| lgA isotype | 8 (12.1) | 2 (6.1) | 6 (18.2) | .13† |

| ISS s III | 38 (57.6) | 15 (45.5) | 23 (69.7) | .05† |

| DS s III | 58 (87.9) | 30 (90.1) | 28 (84.8) | .45† |

| DS A subgroup | 50 (75.6) | 28 (84.8) | 22 (66.7) | .15* |

| Laboratory examination | ||||

| β2M ≥4, mg/L | 46 (69.7) | 19 (57.6) | 27 (81.8) | .03† |

| sCr ≥176.8. μmol/L | 16 (24.2) | 5 (15.2) | 11 (33.3) | .15* |

| LDH ≥190, U/L | 22 (33.3) | 11 (33.3) | 11 (33.3) | 1.00† |

| CRP ≥4, mg/L | 17 (25.8) | 7 (21.2) | 10 (30.3) | .57* |

| ESR ≥100, mm/H | 28 (42.4) | 13 (39.4) | 15 (45.5) | .80* |

| HB ≥100, g/L | 27 (40.9) | 13 (39.4) | 14 (42.4) | .80† |

| ALB ≥35, g/L | 28 (42.4) | 9 (27.3) | 19 (57.6) | .02* |

Two-sided Fisher exact test was used. ALB = serum albumin; BUN = blood urea nitrogen; CRP = C-reactive protein; DS = Durie-Salmin Staging system; ESR = erythrocyte sedimentation; Hb = hemoglobulin; IgA = immunoglobulin A; ISS = International Staging system; LDH = lactate dehydrogenase; β2M = β2-microglobulin; OC = overlap coefficient; sCr = serum creatinine.

Two-sided χ2 test was used.

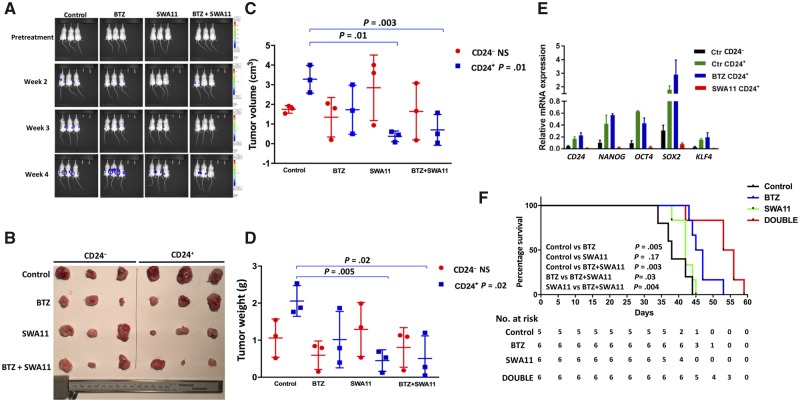

Targeting Myeloma TICs Using a CD24 Antagonist Antibody in Vivo

We have shown that cell surface CD24+ MM cells have TIC features. The CD24 antibody targets cancer cell growth in lung and ovarian cancers (37–39). Therefore, we hypothesized that targeting CD24 might block MM disease progression, thus preventing relapse in MM. In this study, we tested the CD24 antagonizing antibody SWA11 against CD24+ and CD24– ARP1 MM cells using the NOD-Rag1null mouse model as described above. A total of 12 000 CD24– and 12 000 CD24+ ARP1 cells were injected subcutaneously into the left and right flanks of the same NOD-Rag1null mouse. Mice were treated with (1) vehicle, (2) SWA11 10 mg/kg (intraperitoneal injection, 2×/wk), (3) BTZ 3 mg/kg (intraperitoneal injection, 2×/wk), and (4) SWA11 + BTZ. As expected, BTZ had very little effect in reducing tumor burden in CD24+ MM cells, whereas SWA11 or SWA11 + BTZ had a strong effect in targeting CD24+ MM cells (Figure 5A). Tumors were harvested, photographed (Figure 5B), and analyzed for tumor size (cm3) (CD24+ vs CD24+SWA11: 3.28 [0.40] vs 0.38 [0.16], P = .003; CD24+ vs CD24+BTZ+SWA11: 3.28 [0.40] vs 0.70 [0.45], P = .01; Figure 5C) and weight (g) (CD24+ vs CD24+SWA11: 2.06 [0.24] vs 0.45 [0.17], P = .005; CD24+ vs CD24+BTZ+SWA11: 2.06 [0.24] vs 0.51 [0.35], P = .02; Figure 5D) at week 4. Tumor cells were isolated for qRT-PCR to detect the expression of iPS/ES genes. The expression levels of master transcription factors, NANOG, OCT4, SOX2, and KLF4, were statistically significantly downregulated or depleted in CD24+ tumor cells treated with SWA11 (greater than fivefold, P < .001; Figure 5E), suggesting that the CD24 antibody SWA11 targets MM TICs functionally.

Figure 5.

The therapeutic effects of CD24 antibody (SWA11) in xenografted myeloma mouse models. Approximately 12 000 CD24+ and CD24– ARP1 cells were injected into the right and left flanks of NOD-Rag1null mice. Mice were treated with bortezomib (BTZ), SWA11, the combination of BTZ with SWA11, or the control with phosphate-buffered saline for 3 weeks after 1-week injection of tumor cells. A) Multiple myeloma tumors were measured by bioluminescence assay with or without treatments for 4 weeks. B) Tumors from mice described in A were harvested and photographed. C, D) Quantifications of tumors volume (C) and weight (D) from dissected tumors shown in A and B. For the multiple group comparisons, such as Figure 5, C and D, one-way analysis of variance test was used to analyze the four groups in the CD24+ and CD24– populations, respectively. The data are presented as the mean (SD) of triplicate samples. The two-sided t test was used to analyze the differences in tumor volume and weight in CD24+ groups between control (without treatment) vs SWA11; control vs BTZ; control vs BTZ + SWA11; SWA11 vs BTZ + SWA11; and BTZ vs BTZ + SWA11. Only significant comparisons (control vs SWA11 and control vs BTZ + SWA11) are labeled in the figure. E) Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction was performed in dissected tumors described in A and B. The data are presented as the mean (SD) of triplicate samples. P values were calculated using two-sided Student t test. F) Kaplan-Meier curves showing survival of mice treated with BTZ, SWA11, BTZ + SWA11, or vehicle control. The P values presented in this figure were based on the log-rank test. mRNA = messenger RNA; NS = not statistically significant.

To better mimic human MM disease, a hematologic malignancy mainly localized within BM, we repeated the mouse experiments using intravenous injection of parental ARP1 MM cells including both bulk cells and TICs into NOD-Rag1null mice (n = 5 for the control, n = 6 for the other groups). The survival data showed that BTZ, but not SWA11, extended MM mouse survival (days) (46.50 [3.57] vs 39.00 [4.00], P = .005; Figure 5F); and a combination of SWA11 with BTZ further extended MM mouse survival compared with the control (days) (53.17 [5.91] vs 39.00 [4.00], P = .003) as well as to either SWA11 alone (days) (53.17 [5.91] vs 42.17 [2.40], P = .004) or BTZ alone (days) (53.17 [5.91] vs 46.50 [3.56], P = .03). These data suggest that the CD24 antibody may have a better therapeutic effect when bulk MM cells are largely eliminated by chemotherapy, resulting in a low tumor burden with a high percentage of CD24+ MM cells.

Discussion

The cell surface protein CD24 was found to be statistically significantly upregulated in the LC/SP MM cells. To determine whether CD24 is a reliable marker of MM TICs, we isolated CD24+ and CD24– subpopulations from MM cell lines and showed that CD24+ MM cells increased clonogenic potential and drug resistance in vitro and caused tumorigenic in vivo even after injecting only 10 cells from MM cell lines. We also discovered that the size of the CD24+ subpopulation was highly variable and that this subpopulation of CD24+ MM cells was enriched in patients in CR with persistent MRD after chemotherapy. Patients with higher percentages of CD24+ MM cells showed more extensive disease based on the ISS classification system and had more bone lytic lesions. Furthermore, we also confirmed that increased CD24 expression was associated with a poor outcome and inferior response to therapy in newly diagnosed MM patients.

As shown in Figure 1A, we have identified more than 300 statistically significantly expressed genes between side-population and bulk MM cells. It is very likely that other genes may also play important roles in myelomagenesis just like CD24. Therefore, future studies should explore other potential candidates in tumor initiation of MM disease. Another limitation of this study is that we have not yet proven that primary CD24+ MM cells have the same TIC features of increased clonogenesis, tumorigenesis, and drug resistance as shown in the MM cell lines. It is also necessary to confirm the therapeutic effects of CD24 antibodies in primary MM samples in the future.

The property of unlimited self-renewal is shared by pluripotent iPS/ES and cancer stem cells. The core pluripotency factors NANOG, OCT4, and SOX2 collaborate with the accessory proteins LIN28, MYC, and KLF4 to form a self-reinforcing regulatory network that enables the stable expression of self-renewal factors and the repression of genes that promote differentiation (40–42). Our studies both of MM cell lines and primary MM samples showed that CD24+ MM cells had statistically significantly higher expression of iPS/ES genes, including NANOG, OCT4, and SOX2. The CD24 antibody inhibited CD24+ MM cell growth, although it did not show therapeutic effects on CD24– MM cells. Very interestingly, the antagonizing CD24 antibody SWA11 downregulated iPS/ES genes, suggesting that targeting CD24 has a functional impact on MM-initiating cells. Furthermore, a combination of CD24 antibody with the widely used proteasome inhibitor, BTZ, extended MM mouse survival, suggesting that BTZ, which is able to efficiently kill bulk MM cells but not MM TICs, facilitates CD24 antibody efficacy in targeting MM TICs. We did not see a survival benefit with SWA11 alone in MM mice. This is very likely because the parental ARP1 cells are greater than 99% CD24–MM cells. Future investigation could inject bulk MM cells into mice and treat all the animals with BTZ until a clear response is evident (>90% reduction in M protein), after which survival could be assessed following treatment with CD24-specific antibody or control antibodies. Future studies will also evaluate CD24 functional roles in maintaining stemness in primary MM cells and determine whether targeting CD24 or its signaling pathways may eliminate MM TICs. We believe the results of the present studies show exciting promise for a novel approach to eliminate MM TICs, resulting in lasting remission, preventing or delaying disease progression, and relapse in human MM.

Funding

This work was supported by the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society Translational Research Program (6549–18), the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs through the Peer Reviewed Cancer Research Program under Award No. W81XWH-19–1-0500, a generous award from the Myeloma Crowd Research Initiative, the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation (FZ), institutional start-up funds from the Department of Internal Medicine, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa (FZ), Cancer Center Support Grant National Institutes of Health (NIH) number P30 CA086862, NIH grants R21CA187388 and R01CA151354 (SJ), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81529001 and 81570190 to JS), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81670199 to LC). GB is a senior research career scientist of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Notes

The funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; of the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

FZ is a paid consultant for Klyss Biotech; all other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

MG and HB performed the experiments, collected and analyzed the data, generated figures, and wrote and edited the manuscript; YW, YZ, YY, JX, HC, and RFM performed the experiments and collected and analyzed the data; IF supervised the experiments and edited the manuscript; YJ, KN, GT, MS, GB, MT, SJ, and JS discussed the results and edited the manuscript; PA provided the SWA11 antibody and edited the manuscript; LC and GT analyzed the data and edited the manuscript; FZ designed and supervised this study, collected and analyzed the data, and wrote and edited the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Lapidot T, Sirard C, Vormoor J, et al. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature. 1994;367(6464):645–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bonnet D, Dick JE.. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med. 1997;3(7):730–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, et al. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(7):3983–3988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Singh SK, Hawkins C, Clarke ID, et al. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature. 2004;432(7015):396–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ricci-Vitiani L, Lombardi DG, Pilozzi E, et al. Identification and expansion of human colon-cancer-initiating cells. Nature. 2007;445(7123):111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hermann PC, Huber SL, Herrler T, et al. Distinct populations of cancer stem cells determine tumor growth and metastatic activity in human pancreatic cancer. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(3):313–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Franqui-Machin R, Wendlandt EB, Janz S, et al. Cancer stem cells are the cause of drug resistance in multiple myeloma: fact or fiction? Oncotarget. 2015;6(38):40496–40506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Matsui W, Wang Q, Barber JP, et al. Clonogenic multiple myeloma progenitors, stem cell properties, and drug resistance. Cancer Res. 2008;68(1):190–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hideshima T, Mitsiades C, Tonon G, et al. Understanding multiple myeloma pathogenesis in the bone marrow to identify new therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(8):585–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rajkumar SV, Kyle RA.. Multiple myeloma: diagnosis and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80(10):1371–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Palumbo A, Anderson K.. Multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(11):1046–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jakubikova J, Adamia S, Kost-Alimova M, et al. Lenalidomide targets clonogenic side population in multiple myeloma: pathophysiologic and clinical implications. Blood. 2011;117(17):4409–4419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nara M, Teshima K, Watanabe A, et al. Bortezomib reduces the tumorigenicity of multiple myeloma via downregulation of upregulated targets in clonogenic side population cells. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e56954.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Matsui W, Huff CA, Wang Q, et al. Characterization of clonogenic multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 2004;103(6):2332–2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Boucher K, Parquet N, Widen R, et al. Stemness of B-cell progenitors in multiple myeloma bone marrow. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(22):6155–6168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kuranda K, Berthon C, Dupont C, et al. A subpopulation of malignant CD34+CD138+B7-H1+ plasma cells is present in multiple myeloma patients. Exp Hematol. 2010;38(2):124–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yaccoby S, Barlogie B, Epstein J.. Primary myeloma cells growing in SCID-hu mice: a model for studying the biology and treatment of myeloma and its manifestations. Blood. 1998;92(8):2908–2913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yaccoby S, Epstein J.. The proliferative potential of myeloma plasma cells manifest in the SCID-hu host. Blood. 1999;94(10):3576–3582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kim D, Park CY, Medeiros BC, et al. CD19-CD45 low/- CD38 high/CD138+ plasma cells enrich for human tumorigenic myeloma cells. Leukemia. 2012;26(12):2530–2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lim SC. . CD24 and human carcinoma: tumor biological aspects. Biomed Pharmacother. 2005;59(suppl 2):S351–S354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jaggupilli A, Elkord E.. Significance of CD44 and CD24 as cancer stem cell markers: an enduring ambiguity. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:708036. doi: 10.1155/2012/708036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fang X, Zheng P, Tang J, et al. CD24: from A to Z. Cell Mol Immunol. 2010;7(2):100–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee CJ, Dosch J, Simeone DM.. Pancreatic cancer stem cells. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(17):2806–2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Petkova N, Hennenlotter J, Sobiesiak M, et al. Surface CD24 distinguishes between low differentiated and transit-amplifying cells in the basal layer of human prostate. Prostate. 2013;73(14):1576–1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Overdevest JB, Thomas S, Kristiansen G, et al. CD24 offers a therapeutic target for control of bladder cancer metastasis based on a requirement for lung colonization. Cancer Res. 2011;71(11):3802–3811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lee TK, Castilho A, Cheung VC, et al. CD24(+) liver tumor-initiating cells drive self-renewal and tumor initiation through STAT3-mediated NANOG regulation. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9(1):50–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhan F, Barlogie B, Arzoumanian V, et al. Gene-expression signature of benign monoclonal gammopathy evident in multiple myeloma is linked to good prognosis. Blood. 2007;109(4):1692–1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhou W, Yang Y, Xia J, et al. NEK2 induces drug resistance mainly through activation of efflux drug pumps and is associated with poor prognosis in myeloma and other cancers. Cancer Cell. 2013;23(1):48–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhan F, Huang Y, Colla S, et al. The molecular classification of multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;108(6):2020–2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhan F, Hardin J, Kordsmeier B, et al. Global gene expression profiling of multiple myeloma, monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, and normal bone marrow plasma cells. Blood. 2002;99(5):1745–1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zinchuk V, Zinchuk O, Okada T.. Quantitative colocalization analysis of multicolor confocal immunofluorescence microscopy images: pushing pixels to explore biological phenomena. Acta Histochem Cytochem. 2007;40(4):101–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, et al. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414(6859):105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jeong TD, Park CJ, Shim H, et al. Simplified flow cytometric immunophenotyping panel for multiple myeloma, CD56/CD19/CD138(CD38)/CD45, to differentiate neoplastic myeloma cells from reactive plasma cells. Korean J Hematol. 2012;47(4):260–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kovarova L, Buresova I, Buchler T, et al. Phenotype of plasma cells in multiple myeloma and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Neoplasma. 2009;56(6):526–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Raja KRM, Kovarova L, Hajek R.. Review of phenotypic markers used in flow cytometric analysis of MGUS and MM, and applicability of flow cytometry in other plasma cell disorders. Br J Haematol. 2010;149(3):334–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Alaterre E, Raimbault S, Garcia JM, et al. Automated and simplified identification of normal and abnormal plasma cells in multiple myeloma by flow cytometry. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2018;94(3):484–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Salnikov AV, Bretz NP, Perne C, et al. Antibody targeting of CD24 efficiently retards growth and influences cytokine milieu in experimental carcinomas. Br J Cancer. 2013;108(7):1449–1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bretz NP, Salnikov AV, Perne C, et al. CD24 controls Src/STAT3 activity in human tumors. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69(22):3863–3879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kristiansen G, Machado E, Bretz N, et al. Molecular and clinical dissection of CD24 antibody specificity by a comprehensive comparative analysis. Lab Invest. 2010;90(7):1102–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Boyer LA, Lee TI, Cole MF, et al. Core transcriptional regulatory circuitry in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2005;122(6):947–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Orkin SH, Wang J, Kim J, et al. The transcriptional network controlling pluripotency in ES cells. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2008;73:195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang J, Rao S, Chu J, et al. A protein interaction network for pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2006;444(7117):364–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.