Abstract

Background: Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is the most common compressive neuropathy of the upper extremity. We sought to assess the subjective improvement in preoperative symptoms related to CTS, particularly those affecting sleep, and describe opioid consumption postoperatively. Methods: All patients undergoing primary carpal tunnel release (CTR) for electromyographically proven CTS were studied prospectively. All procedures were performed by hand surgery fellowship–trained adult orthopedic and plastic surgeons in the outpatient setting. Patients underwent either endoscopic or open CTR from June 2017 to December 2017. Outcomes assessed were pre- and postoperative Quick Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder and Hand (QuickDASH), visual analog scale (VAS), and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) scores as well as postoperative pain control. Results: Sixty-one patients were enrolled. At 2 weeks, all showed significant (P < .05) improvement in QuickDASH scores. At 6 weeks, 40 patients were available for follow-up. When compared with preoperative scores, QuickDASH (51 vs 24.5; P < .05), VAS (6.7 vs 2.9; P < .05), and PSQI (10.4 vs 6.4; P < .05) scores continued to improve when compared with preoperative scores. At 2-week follow-up, 39 patients responded to the question, “How soon after your carpal tunnel surgery did you notice an improvement in your sleep?” Seventeen patients (43.6%) reported they had improvement in sleep within 24 hours, 12 patients (30.8%) reported improvement between 2 and 3 days postoperatively, 8 patients (20.5%) reported improvement between 4 and 5 days postoperatively, and 2 patients (5.1%) reported improvement between 6 and 7 days postoperatively. Conclusions: The present study demonstrates rapid and sustained improvement in sleep quality and function following CTR.

Keywords: carpal tunnel syndrome, carpal tunnel release, sleep, opioid, narcotic, functional outcomes

Introduction

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is the most common compressive neuropathy of the upper extremity, estimated to occur in nearly 4% of the population.5 CTS refers to the compression of the median nerve at the wrist. Symptoms of carpal tunnel have been well-described and include numbness and tingling in the radial 3 digits and radial side of the ring finger, pain and paresthesias (particularly at night), and weakness of the thenar musculature in advanced cases.6 Physical examination of a patient with CTS can reveal thenar atrophy and decreased sensation in the radial 3½ digits.

CTS is often debilitating for patients at night as they are unable to have restful, uninterrupted sleep due to their symptoms. In the field of hand surgery, numerous conditions have known associations with sleep disorders, and sleep deprivation can adversely affect patient outcomes, function, and satisfaction.3 Insomnia related to CTS is often the primary motivating symptom for patients seeking evaluation and treatment. In a prospective study by Patel et al, they noted 78% of patients had poor sleep quality on validated outcome measures.7

Many nonoperative measures have been utilized for the treatment of CTS and vary from wrist splinting to corticosteroid injection.6 Typically, these nonoperative modalities are reserved for those with mild disease. Patients with moderate-to-severe disease or those whose symptoms progress or persist despite conservative measures often elect for surgical carpal tunnel release (CTR).

Despite the knowledge and incidence of sleep-related symptoms in patients present with CTS, little has been shown in the literature regarding relief of those symptoms after CTR. In addition, little has been published demonstrating postoperative pain control and the consumption of opioid medication. We sought to demonstrate the quantitative improvement in preoperative symptoms related to CTS, particularly those affecting sleep, and characterize opioid consumption postoperatively.

Materials and Methods

After approval from our institutional review board, all patients undergoing CTR for electromyographically (EMG) proven CTS were prospectively solicited to participate in this study. All procedures were performed by 4 hand surgery fellowship–trained adult orthopedic and plastic surgeons in the outpatient setting. Patients underwent either endoscopic or open CTR. Exclusion criteria included prior history of CTR.

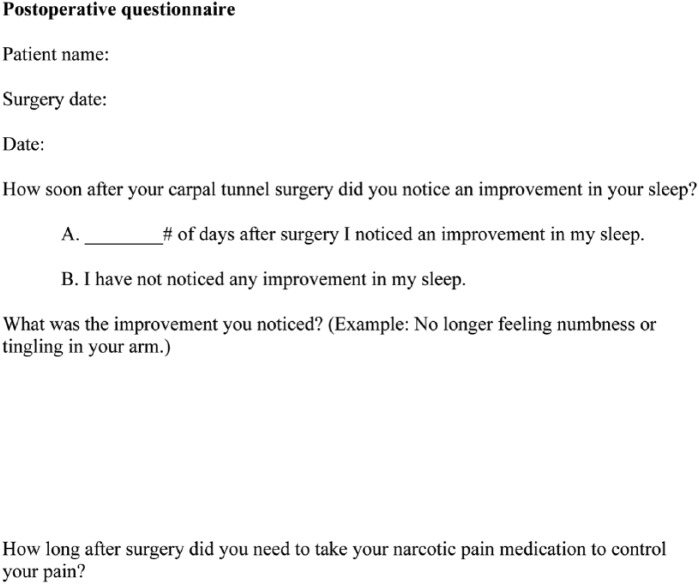

Demographic data were collected. Preoperatively, patients filled out Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), visual analog scale (VAS), and Quick Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder and Hand (QuickDASH). The PSQI is interpreted as a score ⩽5 is considered “good sleep quality,” while a score >5 is considered “poor sleep quality.”2 The VAS was utilized to quantify pain and discomfort related to CTS symptoms in our patient population. The patients were seen at 2 weeks for their first postoperative appointment and were asked to complete the PSQI, VAS, and QuickDASH questionnaires at this time. In addition, they were asked 3 questions: (1) How soon after your carpal tunnel surgery did you notice an improvement in your sleep? (2) What was the improvement you noticed? and (3) How long after surgery did you need to take your narcotic pain medication to control your pain? (Figure 1). The patients were then seen again at 6 weeks postoperatively and asked to complete the PSQI, VAS, and QuickDASH questionnaires.

Figure 1.

Example of the additional questionnaire given to patients postoperatively.

Statistical testing was performed using a standard software package (JMP 13.0, SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). The assumptions for parametric statistical tests including normal distribution and equal variance were met for all continuous variables in this study. A 2-tailed Student t test was used to compare differences in means for continuous variables. Descriptive statistics were generated for the entire sample from the aforementioned questions at the designated time intervals (Figure 1). A 2-tailed Fisher exact test was used to compare differences in the frequency of categorical variables.

Results

A total of 61 patients were enrolled: 47 females and 14 males. Average age of the participants was 52.1 years (range, 26-74 years). Forty-six patients underwent endoscopic CTR while 15 underwent an open CTR. At the 2-week postoperative follow-up appointment, all 61 patients were assessed. When compared with preoperative scores, QuickDASH (51 vs 38.7; P = .002), VAS (6.7 vs 3.5; P = .0001), and PSQI (10.4 vs 7.8; P = .002) scores all demonstrated significant improvement. At 6-week follow-up, only 40 patients were assessed (65.6%). When compared with preoperative scores, QuickDASH (51 vs 24.5; P = .0001), VAS (6.7 vs 2.9; P = .0001), and PSQI (10.4 vs 6.4; P = .0001) scores continued to improve when compared with preoperative scores (Table 1).

Table 1.

Preoperative, 2-Week, and 6-Week QuickDASH, PSQI, and VAS Scores.

| Preoperative (SD) | Two weeks (SD) | Six weeks (SD) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QuickDASH | 51 (22.1) | 38.7 (20.8) | 24.5 (20) | <.05 |

| PSQI | 10.4 (4.7) | 7.8 (4.4) | 6.4 (4.1) | <.05 |

| VAS | 6.7 (2.4) | 3.5 (2.7) | 2.9 (2.8) | <.05 |

| Total | 61 | 61 | 40 |

Note. QuickDASH = Quick Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder, and Hand; PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; VAS = visual analog scale.

At 2-week follow-up, 39 patients responded to the question, “How soon after your carpal tunnel surgery did you notice an improvement in your sleep?” Seventeen patients (43.6%) reported they had improvement in sleep within 24 hours, 12 patients (30.8%) reported improvement between 2 and 3 days postoperatively, 8 patients (20.5%) reported improvement between 4 and 5 days postoperatively, and 2 patients (5.1%) reported improvement between 6 and 7 days postoperatively.

Two-week follow-up responses of 44 patients were recorded for, “What was the improvement you noticed?” Of note, 1 patient may have endorsed relief of more than 1 symptom. The most common symptom improved was improved numbness followed by decreased tingling and subjective improvement in sleep.

Follow-up responses for, “How long after surgery did you need to take your narcotic pain medication to control your pain?” were recorded at 2-week follow-up for 54 patients. Twenty-eight patients (51.8%) stated they only took narcotic pain medication for the first 24 hours, 15 patients (27.8%) reported taking narcotics for 2 or 3 days postoperatively, 4 patients (10.3%) reported taking narcotics for 4 or 5 days postoperatively, 1 patient (1.8%) reported taking narcotics for 6 or 7 days postoperatively, and 6 patients (11.1%) reported taking narcotics for 1 week or longer postoperatively.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates an improvement in sleep, symptoms related to CTS, and minimal narcotic use in the early postoperative period in patients with EMG proven CTS undergoing CTR.

A retrospective study performed in 2009 showed the cost of care of nonoperative treatment of CTS average $3335 while the cost of operative treatment of CTS averaged $3068.9 With the rise in attention given to cost-effective health care in the 21st century, more attention has been directed at patient-reported outcomes and perioperative pain management to understand and evaluate patients in the postoperative setting.

To date, little has been studied regarding the efficacy of CTR on treating one of its most common symptoms: sleep disturbance. Tulipan et al performed a prospective study showing objective improvement in sleep quality within 7 days after CTR, similar to the findings found in the present study.10 When asked about symptoms relief, nearly 70% of patients had less numbness and tingling and 13% endorses better quality of sleep postoperatively within 2 weeks of surgical release.

There has been a burden on physicians, patients, and the health care system at large with the advent of the opioid epidemic in the United States.1 This study showed that approximately 80% of patients only took opioid analgesia for 3 days or fewer postoperatively. In a study by Johnson et al, they reported 13% of opioid-naive patients kept filling opioid prescriptions up to 90 days after common hand procedures, which included CTR.4 Peters et al performed a prospective study analyzing analgesia consumption after outpatient CTR. Forty-nine patients consumed an average of 10 tablets, and the average days of analgesia consumption was 2 days.8 These results are similar to those in the present study.

This study has limitations. Recall bias is present when asking patients to participate in questionnaires. Comorbid conditions that could otherwise be affecting patients’ sleep and/or pain were not factored in; however, it is difficult to say that chronic conditions affecting one’s sleep would result in confounding these data during a 6-week follow-up period. A total of 65.6% of the initially enrolled patients were assessed for the full 6 weeks.

In conclusion, sleep disturbance is a well-documented symptom of CTS. The present study demonstrates rapid and sustained improvement in sleep quality and functional outcomes following CTR. In addition, this study shows the relative brevity with which narcotics are utilized by patients postoperatively, which can help aid in physician prescribing practices, and prevent overprescribing and unnecessary long-term narcotic use in these patients.

Footnotes

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by our institutional review board.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Statement of Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Bohnert AS, Valenstein M, Bair MJ, et al. Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA. 2011;305:1315-1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, III, Monk TH, et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gaspar MP, Kane PM, Jacoby SM, et al. Evaluation and management of sleep disorders in the hand surgery patient. J Hand Surg Am. 2016;41:1019-1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Johnson SP, Chung KC, Zhong L, et al. Risk of prolonged opioid use among opioid-naive patients following common hand surgery procedures. J Hand Surg Am. 2016;41:947-957.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kim PT, Lee HJ, Kim TG, et al. Current approaches for carpal tunnel syndrome. Clin Orthop Surg. 2014;6:253-257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mackinnon SE, Novak CB, eds. Compression neuropathies. In: Wolfe SN, Hotchkiss RN, Pederson W, Kozin SH, eds. Green’s Operative Hand Surgery. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2017:561-638. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Patel A, Culbertson MD, Patel A, et al. The negative effect of carpal tunnel syndrome on sleep quality. Sleep Disord. 2014;2014:962746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Peters B, Izadpanah A, Islur A. Analgesic consumption following outpatient carpal tunnel release. J Hand Surg Am. 2017;7:31161-31163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pomerance J, Zurakowski D, Fine I. The cost-effectiveness of nonsurgical versus surgical treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34:1193-1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tulipan JE, Kim N, Abboudi J, et al. Prospective evaluation of sleep improvement following carpal tunnel release surgery. J Hand Surg Am. 2017;42:390.e1-390.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]