Abstract

Inflammatory and oncogenic signaling, both known to challenge genome stability, are key drivers of BCR-ABL-positive chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and JAK2 V617F-positive chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs). Despite similarities in chronic inflammation and oncogene signaling, major differences in disease course exist. Although BCR-ABL has robust transformation potential, JAK2 V617F-positive polycythemia vera (PV) is characterized by a long and stable latent phase. These differences reflect increased genomic instability of BCR-ABL-positive CML, compared to genome-stable PV with rare cytogenetic abnormalities. Recent studies have implicated BCR-ABL in the development of a "mutator" phenotype fueled by high oxidative damage, deficiencies of DNA repair, and defective ATR-Chk1-dependent genome surveillance, providing a fertile ground for variants compromising the ATM-Chk2-p53 axis protecting chronic phase CML from blast crisis. Conversely, PV cells possess multiple JAK2 V617F-dependent protective mechanisms, which ameliorate replication stress, inflammation-mediated oxidative stress and stress-activated protein kinase signaling, all through up-regulation of RECQL5 helicase, reactive oxygen species buffering system, and DUSP1 actions. These attenuators of genome instability then protect myeloproliferative progenitors from DNA damage and create a barrier preventing cellular stress-associated myelofibrosis. Therefore, a better understanding of BCR-ABL and JAK2 V617F roles in the DNA damage response and disease pathophysiology can help to identify potential dependencies exploitable for therapeutic interventions.

Keywords: DNA damage response, chronic myeloid leukemia, polycythemia vera, ATM-Chk2 pathway

1. Introduction

Chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) are clonal hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) disorders characterized by abnormal proliferation of one or more myeloid lineages. Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), a Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+) chronic MPN, is characterized by the presence of BCR-ABL oncogene [1]. Philadelphia chromosome-negative (Ph¯) MPNs encompass a spectrum of clonal hematological disorders, which include three main clinical entities: polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET), and primary myelofibrosis (PMF) [2]. PV is predominantly associated with oncogenic V617F mutation in the JAK2 gene, detected in more than 95% of cases diagnosed [3,4,5,6]. All MPNs are characterized by chronic inflammatory state (reviewed in [7,8,9]). Thus, oncogenic and inflammatory signaling, both known to fuel genotoxic stress and tumorigenesis in the hematopoietic system in a cell-autonomous and non-cell-autonomous manner, converge in disease evolution of MPNs [10,11,12,13,14]. Therefore, CML and PV provide an excellent model of inflammation-associated neoplasia for investigating mechanisms of DNA damage accumulation and DNA damage response (DDR) activation throughout early pre-cancerous ontogeny.

Apart from a well-established function of the DDR as the intrinsic biological barrier against activated oncogenes and progression of early stages of solid tumors into overt cancer [15,16,17,18,19], the role of the DDR machinery in the development of myeloid neoplasms and acute myeloid leukemias (AML) is being elucidated relatively recently. Indeed, multiple studies have provided evidence on progression of CML and MPN to fully transformed leukemias by selection for mutations in TP53 or other major DDR components [20,21,22], but the detailed hierarchical nature of cooperation between the DDR and inflammatory cytokine network in leukemogenesis has remained poorly understood. We described the DDR checkpoint as a critical mechanism rate-limiting for malignant transformation induced by the mixed lineage leukemia (MLL) oncogenic fusion. Mll-ENL oncogene synergized with inflammatory factors to trigger checkpoint signaling and senescence, thereby counteracting leukemogenesis in a mouse model mimicking human AML [23]. The nature of intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms that alter the DDR during the leukemogenic process of AML development has been recently reviewed by Esposito and So [24] and Nilles and Fahrenkrog [25].

The aim of this review is to discuss the emerging role of DDR alterations in the pathophysiology of two chronic myeloproliferative disease states, BCR-ABL-positive CML and JAK2 V617F-positive PV. We highlight similarities and differences in the DDR landscapes of BCR-ABL- and JAK2 V617F-mutated hematopoietic progenitors, the understanding of which is crucial for therapeutic targeting of these diseases, including synthetic lethality approaches.

2. Role of DDR in CML and PV

The shared and diverse phenotypic characteristics of chronic MPNs have been attributed to dysregulated signal transduction, a consequence of acquired disease-causing oncogenic mutations, BCR-ABL in CML, JAK2 V617F in Ph− MPNs, and several less common oncogenes found in these diseases [26]. Despite similarities in downstream signaling of BCR-ABL and JAK2 V617F, involving the essential role of STAT5 in induction of myeloproliferative malignancy induced by both oncogenes [27,28,29], major differences between the cellular responses triggered by BCR-ABL and JAK2 V617F oncogenes exist. The chimeric BCR-ABL protein is a constitutively active tyrosine kinase [30,31] that shows a robust transformation potential associated with multiple signaling pathways deregulated or activated by BCR-ABL, such as RAS-mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathways [32,33] (reviewed in Ren et al. [34] and Chen et al. [35]). If untreated, the chronic myeloproliferation driven by the BCR-ABL oncogene rapidly progresses to an accelerated phase and terminal blast crisis (BC). In PV, on the other hand, the gain-of-function mutation in the JAK2 gene (JAK2 V617F) constitutively activates type-1 myeloid cytokine receptor-mediated signaling [3,4,5,6,36], resulting in myeloproliferation and systemic inflammation with a protracted clinical course and near-normal life expectancy [37]. These differences in progression of CML and PV suggest distinctions in the nature of BCR-ABL and JAK2 V617F oncogene-induced intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms that govern the myeloproliferation process and its acceleration, including the rate of endogenous DNA damage, DNA damage checkpoint activation, and the extent of genomic instability.

2.1. Role of DDR in Chronic Phase of CML and Progression to Blast Crisis

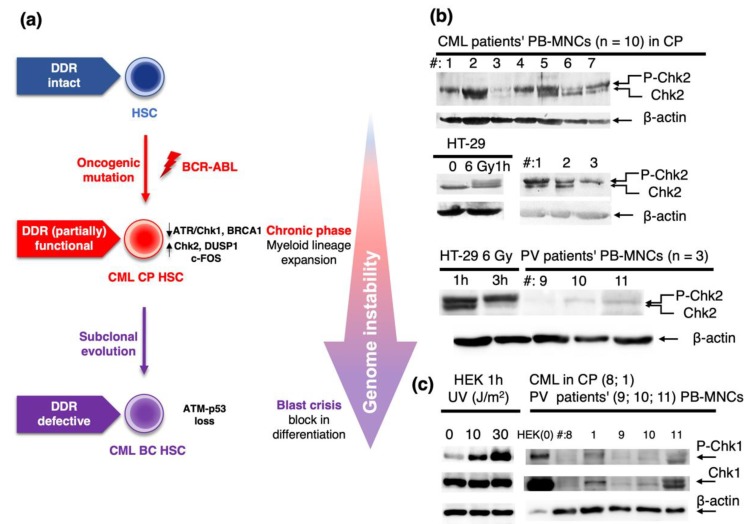

CML is characterized by an indolent, chronic phase (CP) preceding an acute transformation to BC. Failure of DNA damage repair and loss or malfunction of DDR components accompanied by accumulation of DNA damage and genomic instability has been considered in CML evolution [38,39]. It was proposed that BCR-ABL-expressing cells feature reduced activation of the ATR-Chk1-mediated DDR signaling, with ensuing accumulation of substantial genomic instability due to replication stress and oxidative damage. Mechanistically, such disruption of ATR-dependent signaling was attributed to nuclear import of BCR-ABL after DNA damage and its binding to ATR [40]. However, contrasting data were also reported, showing that BCR-ABL does activate ATR-Chk1 signaling, reflecting responsiveness of BCR-ABL-positive myeloid cells to DNA damage following genotoxic treatment [41]. Some studies also addressed functionality of the ATM-Chk2 signaling axis in CML. Thus, c-Abl is a nuclear tyrosine kinase activated by DNA damage in an ATM-dependent manner [42,43]. Even though the BCR-ABL is predominantly localized to the cytoplasm [44], the aforementioned ability of BCR-ABL translocation to the nucleus after DNA damage led to a proposal that BCR-ABL and c-Abl share multiple protein interactions including that with ATM [40]. As a consequence, ATM-mediated activatory phosphorylation of Chk2 was detected in BCR-ABL-expressing cellular models and patient’s cells [40]. These results suggested that ATM-mediated signaling is operational and activated in CP-CML [20], implying that the ATM/Chk2/p53 checkpoint signaling induced by the BCR-ABL oncogene may protect CP-CML cells against the blast crisis. Indeed, inactivating mutations of TP53 were found in up to 30% of cases of BC-CML (reviewed in [20]) and loss of one Atm allele was sufficient for acceleration of the BC in a BCR-ABL transgenic mouse model of CML [45]. Therefore, the ATR-Chk1 and ATM-Chk2 DDR pathways play crucial roles in determination of susceptibility to BC in CML (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

(a) Chronic phase (CP) chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) cells expressing the BCR-ABL oncogenic fusion show partially functional DDR, despite reduced activation of the ATR-Chk1 axis causing failure of genome surveillance and increased genome instability. The DDR is marked by activation of Chk2 and the cells exhibit non-oncogenic addiction to c-FOS and DUSPl expression. Inactivation of TP53 or silencing of Atm signaling leads to fully compromised DDR, allowing acceleration of the disease course to full-blown blast crisis (BC) of CML. (b) Expression and mobility shift of Chk2 were determined by immunoblotting analysis of lysates from seven CML and three polycythemia vera (PV) patients (see Supplementary Table S1 for patients’ numbering and details). HT-29 cells non-irradiated (0) or irradiated with a defined dose of gamma irradiation (6 Gy) and harvested after 1 or 3 h after irradiation were used as a positive control for Chk2 activation. For methodology, see the Appendix A. Upper panels: lysates from seven CML patients in CP; three patients were assayed twice in two different assays. Bottom panel: lysates from three PV patients. (c) Levels of Chk1 phosphorylation at S345 (P-Chk1) and total Chk1 expression in lysates from two CML and three PV patients. HEK cells untreated or UV-treated with a defined dose of radiation (J/m2) were used as a positive control for Chk1 activation. In the patients’ blot, the control HEK cell sample loading was intentionally decreased (compared the β-actin signals) to prevent over-saturated signal on a gel with clinical samples achieving the limit of detection. Patient no. 8 was a CML patient in complete molecular remission after imatinib treatment; no. 1 was a newly diagnosed untreated CML patient. No. 9 was an untreated PV patient, nos. 10 and 11 were PV patients on interferon-α treatment. See also Supplementary Table S1 and Appendix A for details. DDR, DNA damage response; HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; LSC, leukemia stem cell; PB-MNCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

The activation status of Chk2, documented by phosphorylation of Chk2, can be detected by an electrophoretic mobility shift of the Chk2-specific band [46], and multiple phosphorylation sites contribute to this phenomenon [47]. In our yet unpublished study, we analyzed Chk2 activation in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PB-MNCs) isolated from several CML patients in the CP. The Chk2 kinase was activated in all samples, and the phosphorylation-specific band appeared to be strong in most patients (Figure 1b). These data are consistent with recently published evidence for ongoing DNA damage and DDR detected by activated ATM, Chk2, and γH2AX accumulation in PB-MNCs of de novo untreated CP-CML patients [39]. In contrast to strong Chk2 activation in CML cells, lysates prepared from cells obtained from PV patients in their proliferative phase showed only modest evidence of activated Chk2 (i.e., displayed lower signal of phosphorylated Chk2 compared to CML cells), whereas the unphosphorylated form of Chk2 was barely detectable in these samples (Figure 1b). These data indicated an overall lower extent of Chk2 expression and activation in PV cells compared to CP-CML cells. In addition, we confirmed the published data reporting rather low Chk1 expression and phosphorylation at S345 (P-Chk1) in CP-CML cells; nonetheless, comparably low levels of P-Chk1 were observed in lysates from PV patients (Figure 1c).

Although the ATM-Chk2-p53 pathway seems to be activated in CML and protects CP-CML cells from progression to BC, some additional key components of the DDR machinery, such as the BRCA1 tumor suppressor, are downregulated in CML [48,49]. BRCA1 is a major DNA repair gene as it promotes homologous recombination (HR) and replication fork protection, playing critical roles in preserving genomic integrity [50]. Another key component of the HR repair of DNA double strand breaks, RAD51, is upregulated in CML, and BCR-ABL has been shown to boost RAD51’s activity through several mechanisms [51]. Furthermore, expression of DNA-dependent protein kinase, catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs) was shown to be downregulated in CML [52]. DNA-PKcs is an essential part of DNA-dependent protein kinase complex, playing a critical role in DNA double-strand break (DSB) repair and V(d)J recombination. These BCR-ABL-induced effects lead to deregulated HR activity and DNA repair defects, forcing BCR-ABL-expressing cells to rely on unfaithful DSB repair pathways [53,54,55,56,57,58], resulting in disruption of overall genome integrity maintenance. Therefore, these features support a conclusion that BCR-ABL induces a mutator phenotype [59]. Evidence that BRCA/DNA-PK-deficient CML leukemia stem cells are highly sensitive to inhibitors of poly-(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) [60] brought about a potential of targeting key DNA repair enzymes in CML, which are in synthetic lethal relationship with BCR-ABL.

The mutator phenotype of BCR-ABL-expressing cells has been also attributed to increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. BCR-ABL not only enhances ROS production [55,61,62], but it also promotes oxidative stress in CML cells by repressing antioxidant defenses [63]. Elevated ROS are known to modulate activities of signaling pathways involved in malignant proliferation and apoptosis, such as phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/PKB) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways through oxidation of negative feedback loop regulators [64,65,66]. Elevated ROS in BCR-ABL-expressing cells were found to activate PI3k/Akt pathway via inhibition of protein phosphatase 1 α (PP1α) [67].

The BCR-ABL oncoprotein constitutively activates signaling pathways, which under physiological conditions mediate cellular responses to cytokines. Therefore, BCR-ABL oncogenic signaling and growth factor signaling converge to induce the expression of multiple signaling proteins [35]. Kesarwani et al. [68] showed that two such molecules, c-Fos and Dusp1, are overexpressed in CML and constitute non-oncogene addiction in BCR-ABL-induced leukemia. DUSP1 is a member of dual-specificity MAP kinase (MAPK) phosphatases (DUSPs), negative regulators of MAPK signaling in mammalian cells [69]. DUSP1 particularly dephosphorylates stress-activated protein kinase (SAPKs) members of the MAPK superfamily, which include Jun kinases (JNKs) and p38MAPK. The latter kinases are important mediators of DNA damage and inflammatory responses [70]. DUSP1 activity plays a pivotal role in supporting cancer cell survival by buffering SAPK activities under tumor-associated inflammatory conditions [71]. In a CML mouse model, inhibition of Dusp1 activated p38MAPK and sensitized BCR-ABL-positive CML stem cells to imatinib with complete clearance of minimal residual disease [68]. Thus, DUSP1 inhibition is synthetically lethal with BCR-ABL and thus may represent a therapeutic approach for CML.

In conclusion, the oncogenic BCR-ABL activation results in DNA damage, but despite proposed partial reduction of ATR-Chk1 activity, the ATM-Chk2-mediated signaling to p53 and other DDR effectors appears to respond to threshold of genotoxic insults, providing a checkpoint barrier against transformation into BC. The survival of CML cells with damaged DNA has been attributed to inhibition of the Bcl-x(L) deamidation pathway, a mechanism that prevents apoptosis in the presence of high DDR [72]. Supra-threshold amounts of DNA damage and genomic instability that occur as a consequence of BCR-ABL cell autonomous and non-cell-autonomous functions during the course of the disease eventually fuel tumor suppressor barrier inactivation (through selecting for p53 mutations and experimental Atm loss, for example), with the subsequent accelerated progression of untreated CP-CML towards the blast crisis.

2.2. Role of DDR in Polycythemia Vera

As mentioned, PV have a long clinical course and near-normal life expectancy [37]. Despite conditions of systemic inflammation, the chronic proliferation of JAK2 V617F-positive PV is sustained over decades with relatively low cumulative incidence of blast transformation (to AML) and fibrotic progression to post-PV myelofibrosis (post-PV MF, [22,73]). On the contrary, an analogous inflammatory microenvironment triggers oxidative stress and accumulation of damaged DNA, which together with oncogene-induced replication stress causes genomic instability and malignant progression in other inflammation-associated myeloid malignancies such as CML, AML, and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) [62,74]. Indeed, some studies have described JAK2 V617F-dependent accumulation of DSBs [75], increased oxidative DNA damage [76], impaired HR-mediated DSB repair contributing to genomic instability [77], and increased replication fork stalling that provides a potential source of DSBs [78], subsequently leading to a mutator phenotype. However, some of these datasets are in contrast to long-lasting follow-ups of PV patients, who show sustained genome stability with rare occurrence of cytogenetic abnormalities [73,79]. A possible explanation for this discrepancy is that the experimental data obtained from in vitro cultures and mouse models may not be easily transferable to in vivo oncogene behavior in human patients. Particularly in the case of ex vivo-cultured PV patient-derived CD34+ progenitors, one should take into consideration that the hyper-recombination phenotype, observed by Plo et al. [77], was manifested in cells maintained for several days in medium containing DNA damage-promoting cytokines (such as IL-6 [80]) or other growth factors (SCF, IL-3, TPO) promoting ROS production in stimulated human hematopoietic cells [81]. In this regard, we have previously documented that DNA damage protection of JAK2 V617F+ cells is effective under conditions of the relatively modest inflammation-induced degree of DNA damage. These adaptive intrinsic mechanisms are capable of “buffering” the potential genotoxic impact of the cell autonomous and microenvironment-dependent inflammatory stress in PV. However, such a delicate balance can be experimentally altered by enhanced DNA damage and robust activation of the DDR checkpoint response in JAK2 V617F+ cells, higher than that in the JAK2 wild-type (wt) cells [82].

Even though inflammation contributes to the disease transformation towards post-PV MF with increased risk of neoplastic transformation, the most decisive factor that determines MPN progression is acquisition of additional mutations in genes associated with myeloid neoplasms [83,84,85]. Additional mutations acquired usually in genes encoding epigenome modifiers, such as DNMT3A, TET2, or EZH2, that are also shared between MDS and AML patients, have a potential to rewire the biology towards pre-leukemic-like clones [86]. Thus, compared to early leukemogenesis, the disease evolutionary trade-off—bypass of the DNA damage-checkpoint and hence un-opposed proliferation at the expense of an increased genomic instability—seems to be largely avoided in PV.

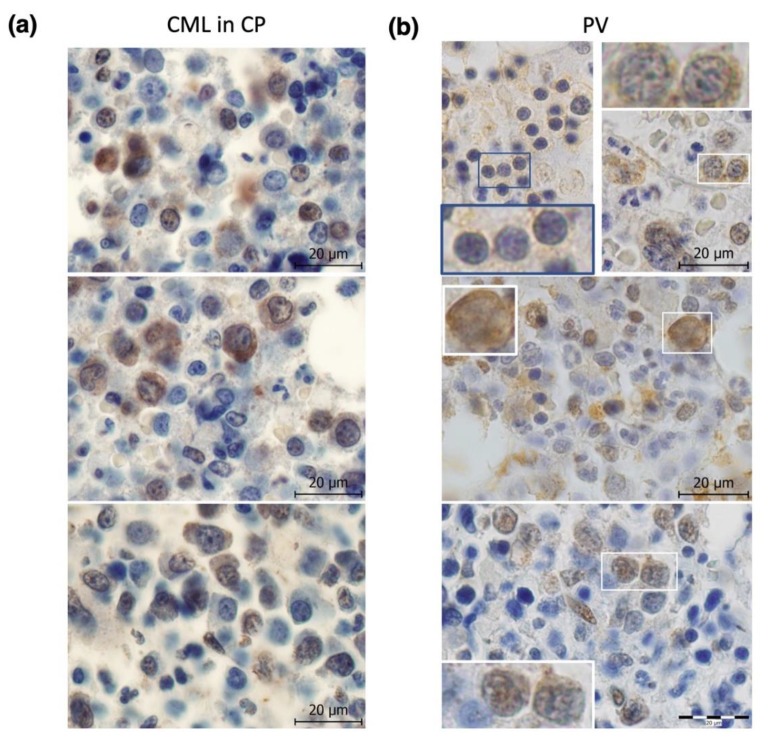

Our own early (unpublished) analysis depicted in Figure 1b revealed differences between Chk2 activation in CML and PV, suggesting differences in functions of its upstream regulator ATM kinase. Although the activated, auto-phosphorylated form of ATM (P-ATM) localizes to the nucleus in bone marrow progenitors of myeloid malignancies including MDS [87,88] and CML ([45] and Figure 2a), our immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining against P-ATM at S1981 revealed predominantly cytoplasmic P-ATM immunoreactivity in PV progenitors and distinct nuclear staining (and lack of cytoplasmic staining) only in post-PV MF ([82] and Figure 2b). These data indicate that although ATM in CML (and MDS and post-PV MF) progenitors regulate its downstream substrates and cell cycle checkpoints mainly from the nucleus, this is different in PV progenitors, where ATM exerts its actions mainly from the cytoplasm. Cytoplasmic activation of ATM in PV likely reflects its response to ROS generated in PV bone marrow inflammatory microenvironment, as ATM phosphorylation by ROS requires its cytoplasmic localization [89]. In addition, the aforementioned extent of Chk2 activation in CML (high) and PV (low) likely reflects subcellular localization of P-ATM [90,91]. Our further (published in [82]) IHC staining of patients’ bone marrow sections from PV revealed low nuclear staining for activated ATR (P-ATR at T1989), and barely detectable expression of a marker for oxidative DNA lesions 8-oxoguanine (8-oxoG), as well as very low staining for a marker of global nuclear DDR activation, Ser 139-phosphorylated histone H2AX (γH2AX) [82]. These data suggested that despite inflammatory microenvironment and JAK2 V617F oncogene-driven myeloproliferation, certain mechanisms must mitigate the potential genotoxic impact of the overall oncogenic program controlled by JAK2 V617F, thereby allowing for PV chronic proliferation with relatively stable genome. Importantly, a gradual increase in the nuclear P-ATM (Figure 2b) and γ-H2AX levels [82] following the progression of PV to post-PV MF implied that such buildup of the DDR threshold signaling is linked to suppression of proliferation and fibrogenesis.

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining for ATM phosphorylation at S1981 (P-ATM) in chronic phase (CP) CML (a) and PV (b) bone marrow trephine biopsies. (a) Upper panel: nuclear staining and middle panel: nuclear and cytoplasmic staining in CML patient no. 15; bottom panel: predominantly nuclear and rare nuclear and cytoplasmic staining in CML patient no. 16. Overall, CML cells show numerous nuclear brightly stained P-ATM foci and variable degree of cytoplasmic P-ATM positivity. (b) Upper panel: PV (#12) with mostly weak but constantly present cytoplasmic staining (details corresponding to blue lined inset on the left and to white lined inset on the right photographs); middle panel: PV with light fibrosis (#13) with cytoplasmic and nuclear positivity; bottom panel: post-PV MF (#14) revealed only nuclear foci staining. See Supplementary Table S1 for patients’ numbering and details. Scale bars, 20 μm. IHC staining was performed as described [82].

According to a recent study, the factor that maintains fork stability of JAK2 V617F-expressing cells in the proliferative phase of MPN is a DNA helicase RECQL5 [92]. Increased RECQL5 expression protected JAK2 V617F-positive erythroblasts from DSB formation and cell death through increased single-stranded annealing-mediated DNA repair, thus contributing to genomic stability. RECQL5 was shown to be a transcriptional target of JAK2 V617F/STAT5, and its knockdown sensitized JAK2 V617F-expressing cells to hydroxyurea [92].

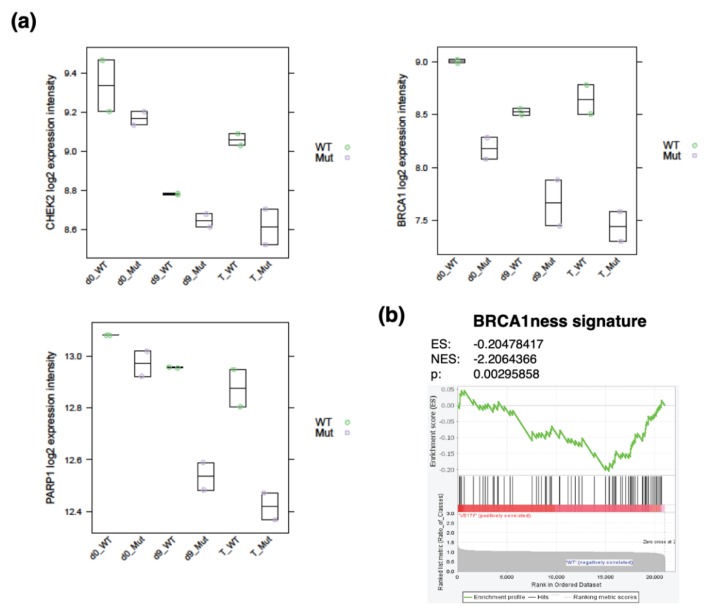

In our recent publication, we further elaborated on the concept of protection mechanisms that guard myeloproliferative progenitors from cell-intrinsic and cell-extrinsic DNA damage and thus DDR, facilitating creation of a barrier preventing cell cycle arrest, myelofibrosis, and rapid malignant transformation in JAK2 V617F-positive PV. We used induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived CD34+ progenitor-enriched cultures (CD34+ P-ECs) from a JAK2 V617F-positive PV patient and from a JAK2 wild-type healthy control [82]. The CD34+ P-ECs were cultured in the absence or presence of IFNγ, TNFα, and TGFβ1, in order to mimic the PV patients’ microenvironment. The JAK2 V617F+ hematopoietic progenitors treated with inflammatory cytokines had slightly increased but tightly controlled ROS levels when compared to their JAK2 wild-type counterparts, and exhibited upregulated expression and activity of key enzymes involved in the ROS buffering system. These progenitors were also less prone to accumulate the 8-oxoG oxidative DNA lesions and the γH2AX DDR activity marker, and their overall modest degree of DDR signaling was compatible with ongoing proliferation. Many markers of DDR were downregulated in inflammatory cytokine-treated JAK2 V617F+ CD34+ P-ECs compared to JAK2 wild-type progenitors, including DNA damage-induced repair gene sets ([82], Figure 3a), suggesting protection mechanisms (such as the above-mentioned RECQL5 or DUSP1, mentioned below) of JAK2 V617F+ PV progenitors against DNA-damaging stimuli, and hence lower demand for enhanced expression of most DDR factors. We did not find any defect in HR in JAK2 V617F+ CD34+ P-ECs [82] and, in fact, the entire BRCA1-associated DNA repair gene set (BRCA1ness, [93]) was significantly enriched for differentially downregulated genes (Figure 3b). Interestingly, BRCA1 downregulation was accompanied by decreased PARP1 expression (Figure 3a). This BRCA1 downregulation does not seem to be dependent on different fractions of JAK2 V617F+ and JAK2 wild-type progenitors in individual cell cycle stages [82], but rather it seems to be an inherent feature of proliferating JAK2 V617F+ PV progenitors, similarly to BRCA1 deficiency in BCR-ABL-proliferating CP-CML [60]. However, in contrast to PV progenitors and to a fraction of AML and MDS samples with downregulated expression of genes in BRCA1 pathway [60], BCR-ABL causes downregulation of BRCA1 protein [60,94].

Figure 3.

Comparison of CHK2 and BRCA1-associated DDR gene expression in induced pluripotent stem cell-derived CD34+ progenitor-enriched cultures (P-ECs) from a JAK2 V617F+ PV patient and from a JAK2 wild-type (wt) healthy control [82]. (a) CHK2, BRCA1, and poly-(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) mRNA expression in day 0 (d0) of undifferentiated and day 9 (d9) differentiated JAK2 wt (WT) and JAK2 V617F+ (Mut) P-ECs, either untreated or treated (T) with inflammatory cytokines IFNγ, TNFα, and TGFβ1 for 24 hours. Two biological replicates per group were used. The plots are based on published gene sets and methodology [82] and linked ArrayExpress database (E-MTAB-7693). (b) Gene set enrichment analysis plot of BRCA1ness signature gene set members ([93]; n = 77) in day 9 of differentiation of JAK2 V617F+ compared to JAK2 wt CD34+ P-ECs. NES, normalized enrichment score.

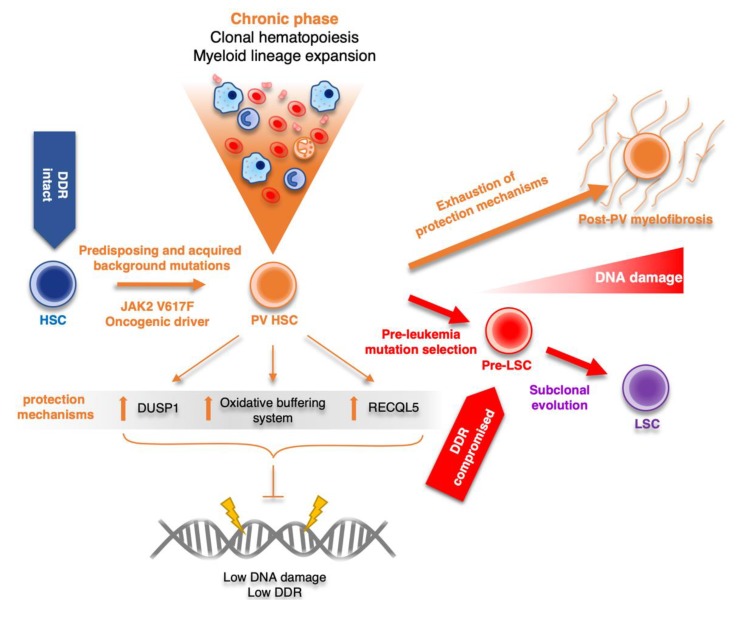

Stimulation of p38MAPK-mediated signaling in chronic inflammatory conditions, such as in PV, would impair proliferation and direct the choice of cell fate towards apoptosis or senescence [95,96], cellular conditions resembling the status of fibrotic bone marrow. Indeed, excessive activation of the p38–MAPK cascade was shown to be associated with PMF [97]. However, the fate of myeloid progenitors in indolent, proliferative PV is at odds with increased SAPK activity. We have shown up-regulation of DUSPs, negative inhibitors of SAPKs, in hematopoietic progenitors derived from PV-patient specific iPSCs, with enrichment of those with substrate specificity for p38 and JNK [82]. We have also detected high expression of DUSP1 in JAK2 V617F+ HEL cells and patients’ bone marrow sections along progression of PV, a factor that was previously shown to be overexpressed also in mouse JAK2 V617F+ BaF3 cells [68]. Additionally, small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated knockdown and pharmacological inhibition of DUSP1 led to JNK/p38MAPK reactivation and accumulation of DNA damage, marked by nuclear γH2AX foci accumulation and accelerated cell cycle arrest and apoptosis of JAK2 V617F+ HEL cells, suggesting dependency on DUSP1 for ongoing cell proliferation and survival [82]. Thus, it seems that cooperation of hyper-activated ROS-buffering system and overexpression of DUSP1 represents an “in-built” feature of the JAK2 V617F oncogene-induced cell rewiring. These mechanisms consequently protect PV progenitors from overall impact of the inflammatory-mediated DNA damage and likely contribute to increased fitness and chronic proliferation of JAK2 V617F+ cells in patients with PV (Figure 4). This model also provides a potential platform for design of novel synthetically lethal therapeutic strategies exploiting JAK2 V617F-mediated protection mechanisms in chronic phase of PV. Thus, JNK/p38MAPK reactivation by inhibition of DUSP1 may provide an early intervention for elimination of the cycling JAK2 V617F-positive PV progenitors. Furthermore, simultaneous targeting of essential ROS buffering system components and thereby escalating oxidative stress could then lead to a robust build-up of lethal DNA damage levels, inducing cell death.

Figure 4.

Schematic model of PV disease evolution, showing the central role of JAK2 V617F-dependent protection mechanisms (upregulation of DUSP1, RECQL5, and oxidative buffering system activity) in the overall long-term maintenance of low DNA damage and genomic stability during the chronic proliferation phase of the disease. Upon exhaustion of protection mechanism capacity, the disease progresses mostly towards post-PV myelofibrosis. In a minor subset of cases, selection of pre-leukemia mutations inhibiting DDR and subclonal evolution towards leukemia stem cell (LSC) marks the onset of secondary acute myeloid leukemias (AML). DDR, DNA damage response; HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; Pre-LSC, pre-leukemia stem cell; LSC, leukemia stem cell.

3. Conclusions

Accumulating DNA damage and chronic inflammation have been suggested as causes for increasing cancer incidence with aging, including incidence of chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms. However, the rate of rise in incidence of BCR-ABL-positive CML with advancing age is less prominent than in JAK2 V617F-positive MPNs [98]. This is consistent with the finding that JAK2 V617F, albeit at low allelic burden, has been detected commonly in aged, healthy individuals, along with clonal hematopoiesis, and has been considered as one of the pre-leukemia-associated mutations [99,100,101,102,103]. As aging in general is associated with increased inflammation, DNA damage, and senescence-associated secretory phenotype, with myeloid skewing in the hematopoietic compartment [104,105]; this likely provides an environment that selects for the expansion of genetic variants such as JAK2 V617F [9]. Consequently, age-related clonal hematopoiesis harboring somatic mutations frequently detected in hematologic malignancies is very common, if not inevitable [106].

Acquisition of JAK2 V617F, in particular, seems to genetically “fix” the already hyperactive JAK2-signaling present in age-associated stressed hematopoiesis [106]. It is also possible that MPN develops as a result of an inflammatory response to the JAK2 V617F clone that occurs frequently in elderly individuals [107].

These data are in accord with the experimental and clinical evidence that BCR-ABL and JAK2 V617F oncogenes in CML and PV, respectively, have different transforming properties. In contrast to highly transforming potential of BCR-ABL, the long latency of chronic indolent phase of JAK2 V617F-positive MPN (with PV being a good example), where the frequency of transformation is relatively low, supports a model in which PV progenitors avoid detrimental effects of oncogenic and oxidative stress and rather utilize signaling adaptations to extrinsic and intrinsic stresses to prevent accumulation of DNA damage. On the basis of our studies and those of others, we conclude that this fail-safe mechanism against inflammatory stress and DNA damage is, at least partially, mediated by direct JAK2 V617F targets, RECQL5 and DUSP1. Both these molecules might provide candidate therapeutic targets, a functionally defined vulnerability targetable in future attempts to provide early intervention, at the chronic proliferative stage of MPNs.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Pavla Koralkova (Department of Biology, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, Palacky University, Olomouc, Czech Republic) for critical reading of the manuscript, Patrik Flodr (Department of Clinical and Molecular Pathology, University Hospital and Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, Palacky University, Olomouc, Czech Republic) for assistance in obtaining data presented in Figure 2, and Michal Kolar (Institute of Molecular Genetics of the ASCR, Prague, Czech Republic) for his technical support in conducting the research leading to data presented in Figure 3.

Supplementary Materials

The following is available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6694/12/4/903/s1, Table S1: Characteristics of patients at the time of sample collection used for Western blotting (depicted in Figure 1b) and immunohistochemical staining (depicted in Figure 2).

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Methodology for Obtaining Previously Unpublished Data

Electrophoretic mobility shift for Chk2 phosphorylation assay, detection of phospho-Chk1. The pellets of CML and PV patients’ leukocytes obtained from heparinized peripheral blood after erythrocyte lysis were washed with ice-cold PBS and lysed in IP buffer with phosphatase and protease inhibitors. As a positive control for phospho-Chk2 detection by electrophoretic mobility shift, HT-29 cells were irradiated with 6 Gy and before lysis cultured for another 1 or 3 h in RPMI 1640 (supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin). Protein lysates were homogenized by vortexing and cleared by centrifugation, and 50 µg of protein per well was subjected to Western blot analysis (10% SDS-PAGE gels) with immunodetection using anti-Chk2 (Merck/Sigma, C9108, 1:500), anti-Chk1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, G-4, 1:1000), anti-phospho-Chk1 (Ser345, Cell Signaling Technology (CST), 133D3, 1:200), and anti-actin (Merck/Sigma, 1:1000) primary antibodies, followed by a secondary antibody labeled with peroxidase (CST, 1:1000). Cold acetone precipitation was used to increase the protein concentration in almost all patients’ protein samples.

Appendix A.2. Patients

The present study included 19 patients (12 in CP-CML; 7 with PV); results from 16 patients are included in Figure 1b and Figure 2, and these patients’ characteristics are summarized in Supplementary Table S1. The study by Stetka et al. [82] included 8 PV patients, 14 samples from PV with myelofibrosis grade ½, and 9 samples from post-PV MF patients; values of both studies contributed to the pathogenic model proposed in Figure 4. Future larger studies involving more patients are warranted to validate this concept.

All participants signed informed consent form to this study which was approved by the Ethics Committee of University Hospital Olomouc, Czech Republic. The approval code from the ethical committee is “P301/12/1503” and the date is 31 March 2011.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.D. and J.B.; methodology, V.D. and J.B.; investigation, J.S., J.L.V., J.G., and R.M.; resources, L.V. and P.V.; data curation, V.D. and J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, V.D., J.S., J.G., and R.M.; writing—review and editing, V.D. and J.B.; visualization, J.S., J.L.V., J.G., and P.V.; supervision, V.D. and J.B.; project administration, V.D. and J.B.; funding acquisition, V.D. and J.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Czech Science Foundation, grant number 17-05988S (VD, JG); Internal Grant Agency of Palacky University, Project IGA_LF_2019_006 (JS and JLV); Danish Cancer Society; and the Swedish Research Council (JB). This project utilized the Czech Centre for Phenogenomics infrastructure, supported by the Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sports and European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) grants LM2018126, OP VaVpI CZ.1.05/2.1.00/19.0395, and CZ.1.05/1.1.00/02.0109.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- 1.de Klein A., van Kessel A.G., Grosveld G., Bartram C.R., Hagemeijer A., Bootsma D., Spurr N.K., Heisterkamp N., Groffen J., Stephenson J.R. A cellular oncogene is translocated to the Philadelphia chromosome in chronic myelocytic leukaemia. Nature. 1982;300:765–767. doi: 10.1038/300765a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arber D.A., Orazi A., Hasserjian R., Thiele J., Borowitz M.J., Le Beau M.M., Bloomfield C.D., Cazzola M., Vardiman J.W. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127:2391–2405. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baxter E.J., Scott L.M., Campbell P.J., East C., Fourouclas N., Swanton S., Vassiliou G.S., Bench A.J., Boyd E.M., Curtin N., et al. Acquired mutation of the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in human myeloproliferative disorders. Lancet. 2005;365:1054–1061. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.James C., Ugo V., Le Couédic J.-P., Staerk J., Delhommeau F., Lacout C., Garçon L., Raslova H., Berger R., Bennaceur-Griscelli A., et al. A unique clonal JAK2 mutation leading to constitutive signalling causes polycythaemia vera. Nature. 2005;434:1144–1148. doi: 10.1038/nature03546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kralovics R., Passamonti F., Buser A.S., Teo S.-S., Tiedt R., Passweg J.R., Tichelli A., Cazzola M., Skoda R.C. A gain-of-function mutation of JAK2 in myeloproliferative disorders. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:1779–1790. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levine R.L., Wadleigh M., Cools J., Ebert B.L., Wernig G., Huntly B.J.P., Boggon T.J., Wlodarska I., Clark J.J., Moore S., et al. Activating mutation in the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and myeloid metaplasia with myelofibrosis. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mirantes C., Passegué E., Pietras E.M. Pro-inflammatory cytokines: Emerging players regulating HSC function in normal and diseased hematopoiesis. Exp. Cell Res. 2014;329:248–254. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hasselbalch H.C., Bjørn M.E. MPNs as Inflammatory Diseases: The Evidence, Consequences, and Perspectives. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015;2015:e102476. doi: 10.1155/2015/102476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Craver B.M., El Alaoui K., Scherber R.M., Fleischman A.G. The Critical Role of Inflammation in the Pathogenesis and Progression of Myeloid Malignancies. Cancers (Basel) 2018;10:104. doi: 10.3390/cancers10040104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reynaud D., Pietras E., Barry-Holson K., Mir A., Binnewies M., Jeanne M., Sala-Torra O., Radich J.P., Passegué E. IL-6 controls leukemic multipotent progenitor cell fate and contributes to chronic myelogenous leukemia development. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:661–673. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang B., Ho Y.W., Huang Q., Maeda T., Lin A., Lee S.-U., Hair A., Holyoake T.L., Huettner C., Bhatia R. Altered microenvironmental regulation of leukemic and normal stem cells in chronic myelogenous leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:577–592. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Welner R.S., Amabile G., Bararia D., Czibere A., Yang H., Zhang H., Pontes L.L.D.F., Ye M., Levantini E., Di Ruscio A., et al. Treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia by blocking cytokine alterations found in normal stem and progenitor cells. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:671–681. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kleppe M., Koche R., Zou L., van Galen P., Hill C.E., Dong L., De Groote S., Papalexi E., Hanasoge Somasundara A.V., Cordner K., et al. Dual Targeting of Oncogenic Activation and Inflammatory Signaling Increases Therapeutic Efficacy in Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. Cancer Cell. 2018;33:29–43.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mendez Luque L.F., Blackmon A.L., Ramanathan G., Fleischman A.G. Key Role of Inflammation in Myeloproliferative Neoplasms: Instigator of Disease Initiation, Progression. and Symptoms. Curr. Hematol. Malig. Rep. 2019;14:145–153. doi: 10.1007/s11899-019-00508-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartkova J., Horejsí Z., Koed K., Krämer A., Tort F., Zieger K., Guldberg P., Sehested M., Nesland J.M., Lukas C., et al. DNA damage response as a candidate anti-cancer barrier in early human tumorigenesis. Nature. 2005;434:864–870. doi: 10.1038/nature03482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorgoulis V.G., Vassiliou L.-V.F., Karakaidos P., Zacharatos P., Kotsinas A., Liloglou T., Venere M., Ditullio R.A., Kastrinakis N.G., Levy B., et al. Activation of the DNA damage checkpoint and genomic instability in human precancerous lesions. Nature. 2005;434:907–913. doi: 10.1038/nature03485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bartkova J., Rezaei N., Liontos M., Karakaidos P., Kletsas D., Issaeva N., Vassiliou L.-V.F., Kolettas E., Niforou K., Zoumpourlis V.C., et al. Oncogene-induced senescence is part of the tumorigenesis barrier imposed by DNA damage checkpoints. Nature. 2006;444:633–637. doi: 10.1038/nature05268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartkova J., Hamerlik P., Stockhausen M.-T., Ehrmann J., Hlobilkova A., Laursen H., Kalita O., Kolar Z., Poulsen H.S., Broholm H., et al. Replication stress and oxidative damage contribute to aberrant constitutive activation of DNA damage signalling in human gliomas. Oncogene. 2010;29:5095–5102. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halazonetis T.D., Gorgoulis V.G., Bartek J. An oncogene-induced DNA damage model for cancer development. Science. 2008;319:1352–1355. doi: 10.1126/science.1140735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melo J.V., Barnes D.J. Chronic myeloid leukaemia as a model of disease evolution in human cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2007;7:441–453. doi: 10.1038/nrc2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rampal R., Ahn J., Abdel-Wahab O., Nahas M., Wang K., Lipson D., Otto G.A., Yelensky R., Hricik T., McKenney A.S., et al. Genomic and functional analysis of leukemic transformation of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:E5401–E5410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407792111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cerquozzi S., Tefferi A. Blast transformation and fibrotic progression in polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia: A literature review of incidence and risk factors. Blood Cancer J. 2015;5:e366. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2015.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takacova S., Slany R., Bartkova J., Stranecky V., Dolezel P., Luzna P., Bartek J., Divoky V. DNA damage response and inflammatory signaling limit the MLL-ENL-induced leukemogenesis in vivo. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:517–531. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Esposito M.T., So C.W.E. DNA damage accumulation and repair defects in acute myeloid leukemia: Implications for pathogenesis, disease progression, and chemotherapy resistance. Chromosoma. 2014;123:545–561. doi: 10.1007/s00412-014-0482-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nilles N., Fahrenkrog B. Taking a Bad Turn: Compromised DNA Damage Response in Leukemia. Cells. 2017;6:11. doi: 10.3390/cells6020011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tefferi A., Gilliland D.G. Oncogenes in myeloproliferative disorders. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:550–566. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.5.3919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nieborowska-Skorska M., Wasik M.A., Slupianek A., Salomoni P., Kitamura T., Calabretta B., Skorski T. Signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)5 activation by BCR/ABL is dependent on intact Src homology (SH)3 and SH2 domains of BCR/ABL and is required for leukemogenesis. J. Exp. Med. 1999;189:1229–1242. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.8.1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walz C., Cross N.C.P., Van Etten R.A., Reiter A. Comparison of mutated ABL1 and JAK2 as oncogenes and drug targets in myeloproliferative disorders. Leukemia. 2008;22:1320–1334. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walz C., Ahmed W., Lazarides K., Betancur M., Patel N., Hennighausen L., Zaleskas V.M., Van Etten R.A. Essential role for Stat5a/b in myeloproliferative neoplasms induced by BCR-ABL1 and JAK2(V617F) in mice. Blood. 2012;119:3550–3560. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-397554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Konopka J.B., Watanabe S.M., Singer J.W., Collins S.J., Witte O.N. Cell lines and clinical isolates derived from Ph1-positive chronic myelogenous leukemia patients express c-abl proteins with a common structural alteration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1985;82:1810–1814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.6.1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Konopka J.B., Witte O.N. Activation of the abl oncogene in murine and human leukemias. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1985;823:1–17. doi: 10.1016/0304-419X(85)90012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lugo T.G., Pendergast A.M., Muller A.J., Witte O.N. Tyrosine kinase activity and transformation potency of bcr-abl oncogene products. Science. 1990;247:1079–1082. doi: 10.1126/science.2408149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gregor T., Bosakova M.K., Nita A., Abraham S.P., Fafilek B., Cernohorsky N.H., Rynes J., Foldynova-Trantirkova S., Zackova D., Mayer J., et al. Elucidation of protein interactions necessary for the maintenance of the BCR-ABL signaling complex. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s00018-019-03397-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ren R. Mechanisms of BCR-ABL in the pathogenesis of chronic myelogenous leukaemia. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2005;5:172–183. doi: 10.1038/nrc1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen Y., Peng C., Li D., Li S. Molecular and cellular bases of chronic myeloid leukemia. Protein Cell. 2010;1:124–132. doi: 10.1007/s13238-010-0016-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilmes S., Hafer M., Vuorio J., Tucker J.A., Winkelmann H., Löchte S., Stanly T.A., Pulgar Prieto K.D., Poojari C., Sharma V., et al. Mechanism of homodimeric cytokine receptor activation and dysregulation by oncogenic mutations. Science. 2020;367:643–652. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw3242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Campbell P.J., Green A.R. The myeloproliferative disorders. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355:2452–2466. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra063728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Calabretta B., Perrotti D. The biology of CML blast crisis. Blood. 2004;103:4010–4022. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Popp H.D., Kohl V., Naumann N., Flach J., Brendel S., Kleiner H., Weiss C., Seifarth W., Saussele S., Hofmann W.-K., et al. DNA Damage and DNA Damage Response in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:1177. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dierov J., Dierova R., Carroll M. BCR/ABL translocates to the nucleus and disrupts an ATR-dependent intra-S phase checkpoint. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:275–285. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(04)00056-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nieborowska-Skorska M., Stoklosa T., Datta M., Czechowska A., Rink L., Slupianek A., Koptyra M., Seferynska I., Krszyna K., Blasiak J., et al. ATR-Chk1 axis protects BCR/ABL leukemia cells from the lethal effect of DNA double-strand breaks. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:994–1000. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.9.2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shafman T., Khanna K.K., Kedar P., Spring K., Kozlov S., Yen T., Hobson K., Gatei M., Zhang N., Watters D., et al. Interaction between ATM protein and c-Abl in response to DNA damage. Nature. 1997;387:520–523. doi: 10.1038/387520a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baskaran R., Wood L.D., Whitaker L.L., Canman C.E., Morgan S.E., Xu Y., Barlow C., Baltimore D., Wynshaw-Boris A., Kastan M.B., et al. Ataxia telangiectasia mutant protein activates c-Abl tyrosine kinase in response to ionizing radiation. Nature. 1997;387:516–519. doi: 10.1038/387516a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wetzler M., Talpaz M., Van Etten R.A., Hirsh-Ginsberg C., Beran M., Kurzrock R. Subcellular localization of Bcr, Abl, and Bcr-Abl proteins in normal and leukemic cells and correlation of expression with myeloid differentiation. J. Clin. Investig. 1993;92:1925–1939. doi: 10.1172/JCI116786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takagi M., Sato M., Piao J., Miyamoto S., Isoda T., Kitagawa M., Honda H., Mizutani S. ATM-dependent DNA damage-response pathway as a determinant in chronic myelogenous leukemia. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2013;12:500–507. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2013.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matsuoka S., Huang M., Elledge S.J. Linkage of ATM to cell cycle regulation by the Chk2 protein kinase. Science. 1998;282:1893–1897. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu X., Tsvetkov L.M., Stern D.F. Chk2 activation and phosphorylation-dependent oligomerization. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:4419–4432. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.12.4419-4432.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deutsch E., Jarrousse S., Buet D., Dugray A., Bonnet M.-L., Vozenin-Brotons M.-C., Guilhot F., Turhan A.G., Feunteun J., Bourhis J. Down-regulation of BRCA1 in BCR-ABL-expressing hematopoietic cells. Blood. 2003;101:4583–4588. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dkhissi F., Aggoune D., Pontis J., Sorel N., Piccirilli N., LeCorf A., Guilhot F., Chomel J.-C., Ait-Si-Ali S., Turhan A.G. The downregulation of BAP1 expression by BCR-ABL reduces the stability of BRCA1 in chronic myeloid leukemia. Exp. Hematol. 2015;43:775–780. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2015.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huen M.S.Y., Sy S.M.H., Chen J. BRCA1 and its toolbox for the maintenance of genome integrity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;11:138–148. doi: 10.1038/nrm2831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Slupianek A., Schmutte C., Tombline G., Nieborowska-Skorska M., Hoser G., Nowicki M.O., Pierce A.J., Fishel R., Skorski T. BCR/ABL regulates mammalian RecA homologs, resulting in drug resistance. Mol. Cell. 2001;8:795–806. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00357-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Deutsch E., Dugray A., AbdulKarim B., Marangoni E., Maggiorella L., Vaganay S., M’Kacher R., Rasy S.D., Eschwege F., Vainchenker W., et al. BCR-ABL down-regulates the DNA repair protein DNA-PKcs. Blood. 2001;97:2084–2090. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.7.2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Slupianek A., Poplawski T., Jozwiakowski S.K., Cramer K., Pytel D., Stoczynska E., Nowicki M.O., Blasiak J., Skorski T. BCR/ABL stimulates WRN to promote survival and genomic instability. Cancer Res. 2011;71:842–851. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Canitrot Y., Laurent G., Astarie-Dequeker C., Bordier C., Cazaux C., Hoffmann J.-S. Enhanced expression and activity of DNA polymerase beta in chronic myelogenous leukemia. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:523–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nowicki M.O., Falinski R., Koptyra M., Slupianek A., Stoklosa T., Gloc E., Nieborowska-Skorska M., Blasiak J., Skorski T. BCR/ABL oncogenic kinase promotes unfaithful repair of the reactive oxygen species-dependent DNA double-strand breaks. Blood. 2004;104:3746–3753. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cramer K., Nieborowska-Skorska M., Koptyra M., Slupianek A., Penserga E.T.P., Eaves C.J., Aulitzky W., Skorski T. BCR/ABL and other kinases from chronic myeloproliferative disorders stimulate single-strand annealing, an unfaithful DNA double-strand break repair. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6884–6888. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gaymes T.J., Mufti G.J., Rassool F.V. Myeloid leukemias have increased activity of the nonhomologous end-joining pathway and concomitant DNA misrepair that is dependent on the Ku70/86 heterodimer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2791–2797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fernandes M.S., Reddy M.M., Gonneville J.R., DeRoo S.C., Podar K., Griffin J.D., Weinstock D.M., Sattler M. BCR-ABL promotes the frequency of mutagenic single-strand annealing DNA repair. Blood. 2009;114:1813–1819. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-172148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dierov J., Sanchez P., Burke B., Padilla-Nash H., Putt M., Ried T., Carroll M. BCR/ABL induces chromosomal instability after genotoxic stress and alters the cell death threshold. Leukemia. 2009;23:279–286. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nieborowska-Skorska M., Sullivan K., Dasgupta Y., Podszywalow-Bartnicka P., Hoser G., Maifrede S., Martinez E., Di Marcantonio D., Bolton-Gillespie E., Cramer-Morales K., et al. Gene expression and mutation-guided synthetic lethality eradicates proliferating and quiescent leukemia cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2017;127:2392–2406. doi: 10.1172/JCI90825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sattler M., Verma S., Shrikhande G., Byrne C.H., Pride Y.B., Winkler T., Greenfield E.A., Salgia R., Griffin J.D. The BCR/ABL tyrosine kinase induces production of reactive oxygen species in hematopoietic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:24273–24278. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002094200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nieborowska-Skorska M., Kopinski P.K., Ray R., Hoser G., Ngaba D., Flis S., Cramer K., Reddy M.M., Koptyra M., Penserga T., et al. Rac2-MRC-cIII-generated ROS cause genomic instability in chronic myeloid leukemia stem cells and primitive progenitors. Blood. 2012;119:4253–4263. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-385658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bourgeais J., Ishac N., Medrzycki M., Brachet-Botineau M., Desbourdes L., Gouilleux-Gruart V., Pecnard E., Rouleux-Bonnin F., Gyan E., Domenech J., et al. Oncogenic STAT5 signaling promotes oxidative stress in chronic myeloid leukemia cells by repressing antioxidant defenses. Oncotarget. 2017;8:41876–41889. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kwon J., Lee S.-R., Yang K.-S., Ahn Y., Kim Y.J., Stadtman E.R., Rhee S.G. Reversible oxidation and inactivation of the tumor suppressor PTEN in cells stimulated with peptide growth factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:16419–16424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407396101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Salmeen A., Andersen J.N., Myers M.P., Meng T.-C., Hinks J.A., Tonks N.K., Barford D. Redox regulation of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B involves a sulphenyl-amide intermediate. Nature. 2003;423:769–773. doi: 10.1038/nature01680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Seth D., Rudolph J. Redox regulation of MAP kinase phosphatase 3. Biochemistry. 2006;45:8476–8487. doi: 10.1021/bi060157p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Naughton R., Quiney C., Turner S.D., Cotter T.G. Bcr-Abl-mediated redox regulation of the PI3K/AKT pathway. Leukemia. 2009;23:1432–1440. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kesarwani M., Kincaid Z., Gomaa A., Huber E., Rohrabaugh S., Siddiqui Z., Bouso M.F., Latif T., Xu M., Komurov K., et al. c-Fos and Dusp1 confer non-oncogene addiction in BCR-ABL induced leukemia. Nat. Med. 2017;23:472–482. doi: 10.1038/nm.4310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kidger A.M., Keyse S.M. The regulation of oncogenic Ras/ERK signalling by dual-specificity mitogen activated protein kinase phosphatases (MKPs) Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016;50:125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee J., Liu L., Levin D.E. Stressing out or stressing in: Intracellular pathways for SAPK activation. Curr. Genet. 2019;65:417–421. doi: 10.1007/s00294-018-0898-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shen J., Zhang Y., Yu H., Shen B., Liang Y., Jin R., Liu X., Shi L., Cai X. Role of DUSP1/MKP1 in tumorigenesis, tumor progression and therapy. Cancer Med. 2016;5:2061–2068. doi: 10.1002/cam4.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhao R., Follows G.A., Beer P.A., Scott L.M., Huntly B.J.P., Green A.R., Alexander D.R. Inhibition of the Bcl-xL Deamidation Pathway in Myeloproliferative Disorders. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;359:2778–2789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tefferi A., Guglielmelli P., Larson D.R., Finke C., Wassie E.A., Pieri L., Gangat N., Fjerza R., Belachew A.A., Lasho T.L., et al. Long-term survival and blast transformation in molecularly annotated essential thrombocythemia, polycythemia vera, and myelofibrosis. Blood. 2014;124:2507–2513. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-579136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sallmyr A., Fan J., Rassool F.V. Genomic instability in myeloid malignancies: Increased reactive oxygen species (ROS), DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) and error-prone repair. Cancer Lett. 2008;270:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li J., Spensberger D., Ahn J.S., Anand S., Beer P.A., Ghevaert C., Chen E., Forrai A., Scott L.M., Ferreira R., et al. JAK2 V617F impairs hematopoietic stem cell function in a conditional knock-in mouse model of JAK2 V617F-positive essential thrombocythemia. Blood. 2010;116:1528–1538. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-259747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Marty C., Lacout C., Droin N., Le Couédic J.-P., Ribrag V., Solary E., Vainchenker W., Villeval J.-L., Plo I. A role for reactive oxygen species in JAK2 V617F myeloproliferative neoplasm progression. Leukemia. 2013;27:2187–2195. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Plo I., Nakatake M., Malivert L., de Villartay J.-P., Giraudier S., Villeval J.-L., Wiesmuller L., Vainchenker W. JAK2 stimulates homologous recombination and genetic instability: Potential implication in the heterogeneity of myeloproliferative disorders. Blood. 2008;112:1402–1412. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-134114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen E., Ahn J.S., Massie C.E., Clynes D., Godfrey A.L., Li J., Park H.J., Nangalia J., Silber Y., Mullally A., et al. JAK2V617F promotes replication fork stalling with disease-restricted impairment of the intra-S checkpoint response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:15190–15195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401873111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Klampfl T., Harutyunyan A., Berg T., Gisslinger B., Schalling M., Bagienski K., Olcaydu D., Passamonti F., Rumi E., Pietra D., et al. Genome integrity of myeloproliferative neoplasms in chronic phase and during disease progression. Blood. 2011;118:167–176. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-331678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kojima H., Kunimoto H., Inoue T., Nakajima K. The STAT3-IGFBP5 axis is critical for IL-6/gp130-induced premature senescence in human fibroblasts. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:730–739. doi: 10.4161/cc.11.4.19172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sattler M., Winkler T., Verma S., Byrne C.H., Shrikhande G., Salgia R., Griffin J.D. Hematopoietic growth factors signal through the formation of reactive oxygen species. Blood. 1999;93:2928–2935. doi: 10.1182/blood.V93.9.2928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stetka J., Vyhlidalova P., Lanikova L., Koralkova P., Gursky J., Hlusi A., Flodr P., Hubackova S., Bartek J., Hodny Z., et al. Addiction to DUSP1 protects JAK2V617F-driven polycythemia vera progenitors against inflammatory stress and DNA damage, allowing chronic proliferation. Oncogene. 2019;38:5627–5642. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-0813-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rumi E., Cazzola M. Diagnosis, risk stratification, and response evaluation in classical myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2017;129:680–692. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-10-695957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shimizu T., Kubovcakova L., Nienhold R., Zmajkovic J., Meyer S.C., Hao-Shen H., Geier F., Dirnhofer S., Guglielmelli P., Vannucchi A.M., et al. Loss of Ezh2 synergizes with JAK2-V617F in initiating myeloproliferative neoplasms and promoting myelofibrosis. J. Exp. Med. 2016;213:1479–1496. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jacquelin S., Straube J., Cooper L., Vu T., Song A., Bywater M., Baxter E., Heidecker M., Wackrow B., Porter A., et al. Jak2V617F and Dnmt3a loss cooperate to induce myelofibrosis through activated enhancer-driven inflammation. Blood. 2018;132:2707–2721. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-04-846220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Feinberg A.P., Koldobskiy M.A., Göndör A. Epigenetic modulators, modifiers and mediators in cancer aetiology and progression. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016;17:284–299. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Horibe S., Takagi M., Unno J., Nagasawa M., Morio T., Arai A., Miura O., Ohta M., Kitagawa M., Mizutani S. DNA damage check points prevent leukemic transformation in myelodysplastic syndrome. Leukemia. 2007;21:2195–2198. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Boehrer S., Adès L., Tajeddine N., Hofmann W.K., Kriener S., Bug G., Ottmann O.G., Ruthardt M., Galluzzi L., Fouassier C., et al. Suppression of the DNA damage response in acute myeloid leukemia versus myelodysplastic syndrome. Oncogene. 2009;28:2205–2218. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhang J., Tripathi D.N., Jing J., Alexander A., Kim J., Powell R.T., Dere R., Tait-Mulder J., Lee J.-H., Paull T.T., et al. ATM functions at the peroxisome to induce pexophagy in response to ROS. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015;17:1259–1269. doi: 10.1038/ncb3230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Alexander A., Walker C.L. Differential localization of ATM is correlated with activation of distinct downstream signaling pathways. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3685–3686. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.18.13253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kozlov S.V., Waardenberg A.J., Engholm-Keller K., Arthur J.W., Graham M.E., Lavin M. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)-Activated ATM-Dependent Phosphorylation of Cytoplasmic Substrates Identified by Large-Scale Phosphoproteomics Screen. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2016;15:1032–1047. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M115.055723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chen E., Ahn J.S., Sykes D.B., Breyfogle L.J., Godfrey A.L., Nangalia J., Ko A., DeAngelo D.J., Green A.R., Mullally A. RECQL5 Suppresses Oncogenic JAK2-Induced Replication Stress and Genomic Instability. Cell Rep. 2015;13:2345–2352. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Severson T.M., Wolf D.M., Yau C., Peeters J., Wehkam D., Schouten P.C., Chin S.-F., Majewski I.J., Michaut M., Bosma A., et al. The BRCA1ness signature is associated significantly with response to PARP inhibitor treatment versus control in the I-SPY 2 randomized neoadjuvant setting. Breast Cancer Res. 2017;19:99. doi: 10.1186/s13058-017-0861-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Podszywalow-Bartnicka P., Wolczyk M., Kusio-Kobialka M., Wolanin K., Skowronek K., Nieborowska-Skorska M., Dasgupta Y., Skorski T., Piwocka K. Downregulation of BRCA1 protein in BCR-ABL1 leukemia cells depends on stress-triggered TIAR-mediated suppression of translation. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:3727–3741. doi: 10.4161/15384101.2014.965013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Iwasa H., Han J., Ishikawa F. Mitogen-activated protein kinase p38 defines the common senescence-signalling pathway. Genes Cells. 2003;8:131–144. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2003.00620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lu M., Zhang W., Li Y., Berenzon D., Wang X., Wang J., Mascarenhas J., Xu M., Hoffman R. Interferon-alpha targets JAK2V617F-positive hematopoietic progenitor cells and acts through the p38 MAPK pathway. Exp. Hematol. 2010;38:472–480. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Desterke C., Bilhou-Nabéra C., Guerton B., Martinaud C., Tonetti C., Clay D., Guglielmelli P., Vannucchi A., Bordessoule D., Hasselbalch H., et al. FLT3-mediated p38-MAPK activation participates in the control of megakaryopoiesis in primary myelofibrosis. Cancer Res. 2011;71:2901–2915. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Srour S.A., Devesa S.S., Morton L.M., Check D.P., Curtis R.E., Linet M.S., Dores G.M. Incidence and patient survival of myeloproliferative neoplasms and myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms in the United States, 2001-12. Br. J. Haematol. 2016;174:382–396. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jaiswal S., Fontanillas P., Flannick J., Manning A., Grauman P.V., Mar B.G., Lindsley R.C., Mermel C.H., Burtt N., Chavez A., et al. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:2488–2498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Xie M., Lu C., Wang J., McLellan M.D., Johnson K.J., Wendl M.C., McMichael J.F., Schmidt H.K., Yellapantula V., Miller C.A., et al. Age-related mutations associated with clonal hematopoietic expansion and malignancies. Nat. Med. 2014;20:1472–1478. doi: 10.1038/nm.3733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Genovese G., Kähler A.K., Handsaker R.E., Lindberg J., Rose S.A., Bakhoum S.F., Chambert K., Mick E., Neale B.M., Fromer M., et al. Clonal hematopoiesis and blood-cancer risk inferred from blood DNA sequence. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:2477–2487. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Young A.L., Challen G.A., Birmann B.M., Druley T.E. Clonal haematopoiesis harbouring AML-associated mutations is ubiquitous in healthy adults. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12484. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Steensma D.P., Bejar R., Jaiswal S., Lindsley R.C., Sekeres M.A., Hasserjian R.P., Ebert B.L. Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential and its distinction from myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2015;126:9–16. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-631747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sun D., Luo M., Jeong M., Rodriguez B., Xia Z., Hannah R., Wang H., Le T., Faull K.F., Chen R., et al. Epigenomic Profiling of Young and Aged HSCs Reveals Concerted Changes during Aging that Reinforce Self-Renewal. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:673–688. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rossi D.J., Bryder D., Zahn J.M., Ahlenius H., Sonu R., Wagers A.J., Weissman I.L. Cell intrinsic alterations underlie hematopoietic stem cell aging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:9194–9199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503280102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Perner F., Perner C., Ernst T., Heidel F.H. Roles of JAK2 in Aging, Inflammation, Hematopoiesis and Malignant Transformation. Cells. 2019;8:854. doi: 10.3390/cells8080854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Fleischman A.G. Inflammation as a Driver of Clonal Evolution in Myeloproliferative Neoplasm. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:606819. doi: 10.1155/2015/606819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.