Abstract

Improving female empowerment is an important human rights and development goal that needs better monitoring. A number of indices have been developed to track female empowerment at the national level, but these are incomplete and may obscure important sub-national variation. We developed the Female Empowerment Index (FEMI) to track multiple domains of women's empowerment at the sub-national level. The index is based on six categories of empowerment: violence against women, employment, education, reproductive healthcare, decision making, and access to contraceptives. The FEMI has a range of zero to one (low to high empowerment), and it is calculated as the mean proportion of positive outcomes in the six categories. To provide a proof of concept, we computed the FEMI for Nigeria and its 36 states from five Demographic and Health Surveys between the years of 1990 and 2013, using questions asked to 98,542 women between 15 and 49 years old. At the national level, the FEMI increased from 0.34 to 0.48. However, there was substantial sub-national variation, with state-level values ranging from 0.16-0.60 in 1990 to 0.19–0.73 in 2013. Our findings thus illustrate the importance of considering sub-national variation in female empowerment. The FEMI can be readily computed for other countries, and its ability to track spatial and temporal variation in woman's empowerment across a broad set of categories may make it more useful than existing approaches.

Keywords: Africa, Nigeria, Women's empowerment, Demographic and health surveys, Gender inequality, Machine learning, Data analytics, Data visualization, Big data, Data mining, Human geography, Social inequality, Human rights, Geography, Sociology, Information science

Africa; Nigeria; women's empowerment; demographic and health surveys; gender inequality; Machine Learning; Data Analytics; Data Visualization; Big Data; Data Mining; Human Geography; Social Inequality; Human Rights; Geography, Sociology, Information Science.

1. Introduction

Increasing the empowerment of women is a major human rights and development goal (Gates, 2014; UN General Assembly, 2014), but progress in women's empowerment lags behind development goals in other domains, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa (United Nations, 2015). In addition to its intrinsic human rights value, empowering women can result in benefits for societies at large. For example, increases in women's empowerment can lower infant and child mortality (Gakidou et al., 2010; Knippenberg et al., 2005) and improve health and nutrition. Improvements in women's education are also linked to strong gains in income (Psacharopoulos, 1994).

Meaningful indicators are necessary to identify and understand patterns and trends in women's empowerment to guide and evaluate policy and other intervention efforts. Unfortunately, detailed spatial and temporal data on indicators of female empowerment are generally lacking (UN Women 2016). Furthermore, empowerment has multiple dimensions, and there is no one obvious way to measure it. Different empowerment approaches have been developed by the UNDP, including the Gender Development Index (GDI) and Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM) (UNDP, 1995), and the follow-up Gender Inequality Index (GII) (Gaye et al., 2010). The Gender Development Index (GDI) uses data on life expectancy, literacy and educational enrollment rates, and income. The Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM) uses data on higher-status employment positions, political participation, and income. Both the GDI and GEM primarily focus on “gender gaps”, that is, differences between women and men. The GII was designed to address some of the criticisms of the GDI and GEM. It captures aspects of reproductive healthcare via the maternal mortality rate and adolescent birth rate, as well as education rates, parliamentary representation, and labor force participation rates. The GII takes into account both absolute values (for women only) as well as relative values (gender-gaps). However, aspects of decision making and personal security are not included. The Global Gender Gap Index (GGGI) (World Economic Forum, 2019) is an alternative index created by the World Economic Forum to highlight national-level achievement gaps between women and men in four categories: Economic Participation and Opportunity, Educational Attainment, Health and Survival and Political Empowerment. It exclusively focuses on gender gaps.

A primary limitation of the indices discussed above is that they have been designed for and computed at the national level, obscuring within-country variation that may be important for policymaking and intervention efforts. Their utility has also been limited by using variables that are widely available, but not necessarily most indicative of women's empowerment. This is particularly problematic for assessing the status of women within lower economic strata. For example, the variables used for employment categories largely pertain to the most educated and economically advantaged women because the available data ignored the informal employment sector (Beteta and Hanny, 2006). Another criticism of these measures is their lack of information on important empowerment dimensions such as decision making and personal security (Hirway and Mahadevia, 1996; Klasen, 2006).

The increasing availability of nationally representative survey data has created opportunities to more fully capture women's empowerment by including additional dimensions of empowerment. Ewerling et al. (2017) used Principal Component Analysis with 15 questions from the Demographic and Health Surveys across Africa to compare countries nationally in three domains of female empowerment: attitude to violence, decision making, and social independence.

In an effort to improve upon existing measures in gender inequality, and to better understand the changes in the empowerment of women over space and time, we developed the Female Empowerment Index (FEMI). The FEMI uses nationally representative survey data to compute sub-national variation in important aspects of empowerment, some of which were not included in previous indices: all types of employment, personal agency and decision making, physical and sexual violence, and access to reproductive health services. Apart from adding these domains of empowerment, the FEMI also addresses shortcomings in previous indices by including both the formal and informal employment sector and considers both gender gaps and absolute levels of empowerment. The FEMI can be computed with the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) data, which are available for most countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, and for many countries in Asia and the Americas. The FEMI is computed by averaging scores in six empowerment categories: violence against women, employment, education, reproductive healthcare, decision making, and access to contraceptives. To illustrate its use, we implemented the FEMI for the 36 states of Nigeria, using 19 questions from DHS for five survey years.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Data sources

We used all available data from the Demographic Health Surveys (DHS) program in Nigeria for the years 1990, 1999, 2003, 2008, and 2013 (ICF International, 1992–2014). These years represent all standard DHS surveys conducted in country to date. In total, 98,542 women aged 15–49 years were interviewed using a nationally representative cluster-sampling approach. The first three surveys had smaller sample sizes; the average number of women interviewed was around 8,200 for the first three surveys and 36,000 for the last two. Table 1 summarizes some of the general characteristics of the population surveyed across years.

Table 1.

Mean characteristics of women for the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) in Nigeria, by survey year. Characteristics that were not included in a given survey are marked with “-”

| Characteristic | Survey Year |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 1999 | 2003 | 2008 | 2013 | |

| Age | 28.17 | 27.95 | 28.02 | 28.65 | 28.86 |

| Wealth Quintile | - | - | 3.07 | 2.92 | 3.12 |

| Married | 76.3% | 70.2% | 67.7% | 71.8% | 70.0% |

| Number of Children | 3.20 | 2.84 | 3.02 | 3.14 | 3.07 |

| Religion | |||||

| Christian | 47.3% | 53.9% | 51.0% | 51.7% | 51.2% |

| Islam | 48.7% | 44.3% | 47.3% | 46.5% | 47.9% |

| Traditional/Other/None | 4.0% | 1.8% | 1.7% | 1.8% | 0.9% |

The actual number of responses varied by question (Table 2), as some questions were asked only to certain categories of women, specifically access to contraception, reproductive healthcare, and employment.

Table 2.

Effective sample size by FEMI category, and number of survey sites (“clusters”) for the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) in Nigeria, by survey year. Categories that were not included in a survey year are marked with “-”.

| Category | Survey Year |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 1999 | 2003 | 2008 | 2013 | |

| Violence against Women | 7079 | 6081 | 7473 | 32825 | 38551 |

| Employment | - | 8166 | 7613 | 33326 | 38913 |

| Education | 8767 | 8180 | 7620 | 33383 | 38945 |

| Reproductive Healthcare | 4873 | 3067 | 3767 | 17995 | 20192 |

| Decision Making | - | - | 7374 | 23880 | 27210 |

| Access to Contraception | 1987 | 2135 | 2686 | 12220 | 14687 |

| Number of Sites | 299 | 399 | 365 | 888 | 904 |

Categories were created based on either the responses to single questions (employment and contraception) or on the mean response to several related questions (education, decision making, violence against women, and reproductive healthcare; Table 3). All responses were recoded such that their values ranged between zero and one, where zero represents low levels of empowerment and one represents high empowerment. Thus, the value of a given FEMI category can be interpreted as “the proportion of positive outcomes in this category”. The FEMI index was calculated as the mean of all categories and has a theoretical range of zero to one, with one being the highest level of empowerment.

Table 3.

Categories, questions, and years of data in which a given question was not asked (i.e., values were imputed). Answers to all questions were converted to Yes/No.

| Category | Question | Years of Estimation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Violence Against Women | Childhood marriage: Did respondent have a child before the age of 18? | ||

| Is beating justified if respondent goes out without telling her partner? | 1990, 1999 | ||

| Is beating justified if respondent neglects the children? | 1990, 1999 | ||

| Is beating justified if respondent argues with her partner? | 1990, 1999 | ||

| Is beating justified if respondent refuses to have sex? | 1990, 1999 | ||

| Is beating justified if respondent burns the food? | 1990, 1999 | ||

| Employment | Have you had paid employment (cash or in-kind) within the past 12 months? | 1990 | |

| Education | Primary educational attendance: Did respondent attend at least 6 years of school? | 1990 (men only) | |

| Literacy: Can respondent read a short paragraph shown to them? | 1990, 1999 | ||

| Reproductive Healthcare | Did respondent have a prenatal visit for her most recent child? | ||

| Childhood birth: Did respondent have a child before the age of 18? | |||

| Was respondent's most recent child delivered in a professional setting? | |||

| Decision Making | Does respondent have a say in her health? | 1990, 1999 | |

| Does respondent have a say in large purchases? | 1990, 1999 | ||

| Does respondent have a say in household purchases? | 1990, 1999, 2013 | ||

| Does respondent have a say in visits to family? | 1990, 1999 | ||

| Does respondent have a say in food to be cooked? | 1990, 1999, 2008, 2013 | ||

| Does respondent have a say in deciding what to do with money? | 1990, 1999, 2003 | ||

| Access to Contraception | Are you using modern contraception if you are married and do not currently desire more children? | ||

Responses from individual women were aggregated to state level for the 36 Nigerian states using the geographic coordinates of the survey sites (referred to as “clusters” by DHS). In 1990, Nigeria had only 30 states. In order to allow direct comparisons to later surveys, we aggregated the individual 1990 data to the modern 36 states based on where they would have lived in the newer 36 state scheme. In addition, the 1999 survey did not release survey site coordinates; the only geographic reference provided for a respondent was being in one of five large regions, each consisting of multiple states. To allow direct comparison between this survey and other surveys, we downscaled the responses for this survey by taking the year-weighted mean of the 1990 and 2003 surveys for each state and applying a linear adjustment factor to ensure that the overall regional mean matched that of the original 1999 survey regions.

Some categories were not included in all surveys (Table 3). Responses to the questions in these categories were estimated at the state level using RandomForest (Breiman, 2001). Predictor variables used were responses to questions that were available for all surveys: year, access to contraceptives, reproductive healthcare, age at first marriage, age at first child, years of education, milieu (urban/rural), respondent's age, number of respondent's births in the last 5 years, and geographic coordinates of the respondent's state. For the men's employment and education questions, year, milieu (urban/rural), respondent's age, and geographic coordinates of the respondent's location were used as predictor variables.

In some cases one can either examine absolute values for women's empowerment in a particular category or express them relative to men's achievement in the same category. For the education and employment categories, we chose to use relative values. These were computed for each state by multiplying them by the inequality coefficient (women's value/men's value, capped at one):

This method was chosen because it results in the highest adjustment for states that have both high absolute levels and high relative differences. For example, if 60% of women and 80% of men have primary education, the unadjusted value would be 0.60 and the inequality-adjusted value would be 0.60 × (0.60 ÷ 0.80) = 0.45, for an absolute decrease of 0.15. However, if 20% of the women and 40% of the men have primary education (the same 20% difference), the unadjusted value would be 0.20 and the inequality-adjusted value would be decrease to 0.20 × (0.20 ÷ 0.40) = 0.10, for an absolute decrease of 0.10. The heavier penalization of regions that have relatively high welfare but high levels of inequality is desirable, as it helps to avoid giving low scores to regions for merely being poor. Adjustment was unnecessary for the decision-making category because questions in this category already account for differences in women's and men's decision making, and adjustment was irrelevant for the reproductive healthcare, violence against women, and access to contraception categories.

To ensure that our results were not skewed by using DHS data sub-nationally (most DHS statistics are aggregated to the national level in reporting), we examined several potential areas of concern. First, DHS surveys oversample poor and rural households. This is normally corrected for when computing national level aggregate values by using DHS-provided weights. Because of a lack of data on state-level wealth distributions, we have used unweighted data for each state, which may artificially lower values for wealthier states. To assess the potential impact of this issue, we created national unweighted values by taking the unweighted mean of state level categories for each year and compared them to the DHS-weighted national category results.

Additionally, aggregating DHS data by sub-national regions rather than for the entire country could result in noisy data due to lower sample sizes. This would be of particular concern for the 1990–2003 surveys, as they have a lower sample size compared to the later surveys, with an average of 248 individuals sampled per state in the 1990, 1999, and 2003 surveys, whereas 1,005 individuals were sampled per state in the latter two surveys. We evaluated the degree to which the data was spatially noisy by computing Moran's I, a measure of spatial autocorrelation, for each category of the FEMI. Spatial autocorrelation expresses the extent to which geographically near regions are more similar to each other than geographically distant regions. For most development indicators we would expect high levels of positive spatial autocorrelation, and low spatial autocorrelation values would then suggest poor data quality, perhaps due to a low sample size. Moran's I runs from negative one (complete negative spatial autocorrelation) to one (complete positive spatial autocorrelation). We tested these results for statistical significance by comparing observed statistics to Monte-Carlo-simulated distributions (n = 999).

A final issue we considered is the effect of a time lag for certain indicators like education and age at first marriage. As the index is computed for women between ages 15 and 49, a cohort of women is in the sample for 34 years (that is, longer than the 23 year span of the five surveys we used). This may dampen the apparent changes for some questions and categories. For example, a woman first married at the age of 15 will still have that status when she is 49, even if the practice of adolescent marriage has become much less common in more recent years. Educational achievement is similarly affected. To detect potential dampening of changes, we analyzed the values for applicable categories by adjusting for the current age of respondent (as of 2013).

2.2. Computation of the empowerment categories

2.2.1. Violence against women

The DHS surveys include questions on women's direct experience with physical and sexual violence. The survey data suggested that about 5% of Nigerian women experienced physical and/or sexual violence across survey periods. This is much lower than reported rates of 21%–36% for physical violence and 33%–64% for sexual violence (Antai and Antai, 2008; Fawole et al., 2005; Ilika et al., 2002; Okemgbo et al., 2002; Okenwa et al., 2009; Olagbuji et al., 2010). This discrepancy is probably due to a reluctance to report on this sensitive issue (Oyediran and Feyisetan, 2017). Because of this concern about the data quality, we instead used five questions related to attitudes regarding the justification of violence as a proxy for physical violence (see Antai and Antai, 2008; Oyediran and Isiugo-Abanihe, 2005). For sexual violence, adolescent marriage was used as a proxy, both because it indicates a lack of control over a woman's sexual choices (Nour, 2006) and because early marriage may be considered an act of sexual violence in its own right (Gottschalk, 2007). The overall score was calculated as the mean of the averaged justification of physical violence questions and adolescent marriage rates to represent an equal weight between physical and sexual violence. We refer to this score in shorthand as “violence against women”, but note that the actual numbers are partly based on female attitudes toward physical violence.

2.2.2. Employment

All women who received payment for labor in the 12 months prior to the interview were counted as employed. This included women who were paid in cash, in-kind, or a combination of the two; unpaid work was excluded. Including in-kind and mixed payments helps bridge the gap between the formal and informal employment sectors, the latter of which is an important source of employment for many women in rural and lower income areas. This category includes seasonal and occasional work, and should not be interpreted as the number of women who have steady paid jobs. The employment data was available for married women only, and for this reason it had a smaller sample size than other categories.

2.2.3. Education

The educational category was computed as the average of the responses to two questions. Primary educational rates were calculated as the proportion of women who attended at least six years of schooling. Literacy rates were calculated as the proportion of women who could read a simple paragraph without difficulty. Those who couldn't read, or read only with difficulty, were categorized as unable to read.

2.2.4. Reproductive healthcare

The reproductive healthcare category was computed as the average of the responses to three reproductive health questions (Table 3). No imputation was needed for this category.

2.2.5. Decision making

The decision making category was computed as the average of the answers to six questions. The answers “self” and “self and partner” in response to questions regarding who had the primary say in different aspects of decision making were combined into “yes” (Table 3).

2.2.6. Contraception

For the contraception category, we wanted to capture whether women in need of contraception were able to obtain and use it. Our methods are based on the STATA code released by DHS (Bradley and Croft, 2017) that follows the methods of Bradley et al. (2012). It should be noted that their publicly available code does not match their stated methodology (i.e. they claim to measure only married women, but their code does not actually exclude unmarried women from analysis, except in some infecundity checks). We have fixed the code to examine only married women as recommended by DHS, and we have fixed several errors that misclassify women who have missing data, as well as a typo that misclassified infecund women incorrectly.

We then used a modified recoding of the results to reflect our particular needs. In essence, our sample was first restricted to married fecund women who did not want more children at the time of the survey. These women were then classified based on whether or not they were currently using modern contraceptive methods. Unmarried women, infecund women, women who wanted additional children at the time of the survey, and those using traditional methods (e.g., withdrawal) or folklore-based methods (e.g., charms) were removed from analysis. This categorization is an improvement over the original DHS methods for our purposes because our method only includes women who do not currently want children in the analysis. DHS counts women who currently want children as having access to contraception, when that may or may not be true. However, this resulted in a lower sample size than for other categories (see Table 2).

2.3. Regions

Several empowerment categories showed a strong north/south divide. Nigeria is commonly grouped into six regional geopolitical zones. For the purposes of reporting some of the differences between north and south, we combined the North West and North East geopolitical zones, representing roughly the northern third of the country, into the “North” region (the states of Adamawa, Bauchi, Borno, Gombe, Jigawa, Kaduna, Katsina, Kano, Kebbi, Sokoto, Taraba, Yobe and Zamfara). The North Central zone (representing the middle third of the country) was combined with the three southern zones to create the “South” region (all other states).

3. Results

3.1. Data quality

Our ability to impute missing data had variable quality, with R2 values between .28 and .97 (Table 4). Estimation quality was significantly bolstered by strong temporal trends in the data; time (survey year) was the most important predictor for all estimated variables.

Table 4.

Model fit for the Random Forest estimation of missing values. R2 values are internally calculated by Random Forest using the OOB (“out of bag”) data that were not included in the bootstrapped sample for a particular decision tree. R2 values for questions that were only estimated for men or were estimated for both men and women are labeled with M and W, respectively. Unmarked values apply to women. Questions not in the Table did not need imputation.

| Category | Question | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| Violence Against Women | Is beating justified if respondent goes out without telling her partner? | 0.56 |

| Is beating justified if respondent neglects the children? | 0.44 | |

| Is beating justified if respondent argues with her partner? | 0.40 | |

| Is beating justified if respondent refuses to have sex? | 0.57 | |

| Is beating justified if respondent burns the food? | 0.43 | |

| Employment | Has respondent had paid employment (cash or in-kind) within the past 12 months? | W: 0.28 M: 0.31 |

| Education | Can respondent read a short paragraph shown to them? | W: 0.97 M: 0.75 |

| Did respondent attend at least 6 years of school? | M: 0.66 | |

| Decision Making | Does respondent have a say in her health? | 0.72 |

| Does respondent have a say in large purchases? | 0.74 | |

| Does respondent have a say in household purchases? | 0.70 | |

| Does respondent have a say in visits to family? | 0.62 | |

| Does respondent have a say in food to be cooked? | 0.51 | |

| Does respondent have a say in deciding what to do with money? | 0.54 |

In testing for potential inaccuracies due to our use of unweighted state-level values, we calculated both the unweighted national means using the raw data and the weighted national means using the DHS-provided weights, and then calculated the absolute value of the differences. We found that the overall mean difference in FEMI categories was 0.03. Violence was the least affected with a difference of 0.01 and access to contraception was the most affected with a difference of 0.06. These results suggest that the effect of using unweighted averages is generally small within individual categories and for the FEMI, although there does appear to be some mild suppression of FEMI values in wealthier states for access to contraception.

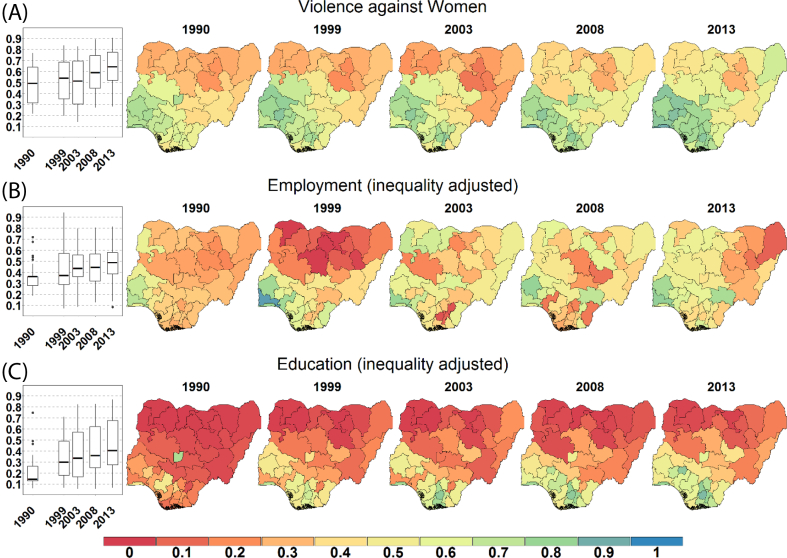

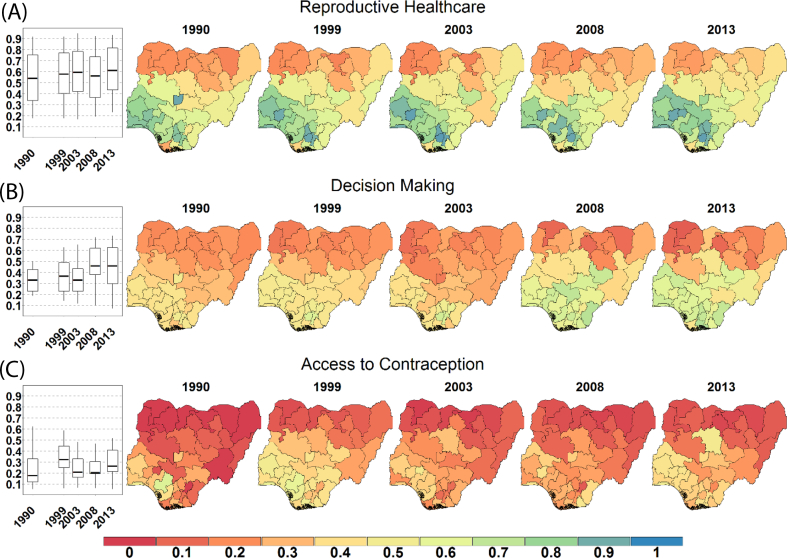

Excessive noise due to reduced sample size did not appear to be a major problem. We found that there were strong signs of spatial autocorrelation in each FEMI category, as well as consistent patterns over time (Figures 1 and 2). Moran's I values were above 0.60 for all categories except for contraception (0.51) and employment (0.39), indicating moderate to strong positive spatial autocorrelation. All Moran's I values were significantly different from zero at the α = 0.05 level except for the employment category for 2008 (p-value = 0.13).

Figure 1.

Three FEMI categories in Nigeria at the national (boxplot) and state level (maps) between 1990 and 2013. Boxplots were made using state level data, but with the median (thick horizontal bar) adjusted for population size to better reflect the true national median. (A) Violence against women. Higher values indicate lower levels of violence. (B) Inequality-adjusted employment of women. (C) Inequality-adjusted educational achievements by women. All three categories are calculated from the mean values in their respective categories, and then employment and education were adjusted for inequality between women and men.

Figure 2.

Three FEMI categories in Nigeria at the national (boxplot) and state level (maps) between 1990 and 2013. Boxplots were made using state level data, but with the median (thick horizontal bar) adjusted for population size to better reflect the true national median. (A) Reproductive healthcare of women. (B) Participation in decision making regarding their personal lives by women. Higher levels indicate greater control over decision making. (C) Access to contraception.

3.2. Violence against women

The experience and acceptability of violence against women decreased steadily over time, with the score for this category improving by 0.07 per decade (Figure 1). Violence against women is much more common in northern Nigeria, with adolescent marriage rates approaching 65% in the North in 2013 versus 23% in the South. However, the reported acceptability of violence declined at a comparable rate in the North and South. In northern states, the category went from 0.48 to 0.71 (0.10 per decade) and in southern states went from 0.67 to 0.82 (0.07 per decade) between 1999 and 2013.

3.3. Employment

Inequality-adjusted participation in gainful employment for women increased from 0.37 in 1990 to 0.49 in 2013 (Figure 1). The national equality gap was slightly lower in the 1990s (average of 0.67) and higher thereafter (average of 0.82) (Table 5). Employment for women lacks the typical north/south differences found among other FEMI categories which may indicate either relative geographical equality or noise in the data. Results for 1990 in particular should be interpreted with caution as these values were imputed with a RandomForest model for which the R2 was only 0.28 for women and 0.31 for men.

Table 5.

Mean weighted national original FEMI category values, gender inequality coefficients (ratio of women's/men's rates), and adjusted FEMI category values for the education and employment categories for the years 1990–2013 in Nigeria. The inequality-adjusted value is calculated by multiplying the original value by the relative inequality gap, which is the ratio of women's achievement to men's achievement.

| Year |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 1999 | 2003 | 2008 | 2013 | ||

| Education | Original value | 0.27 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.49 |

| Inequality coefficient | 0.40 | 0.64 | 0.63 | 0.65 | 0.69 | |

| Adjusted value | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.41 | |

| Employment | Original Value | 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.51 | 0.52 | 0.59 |

| Inequality coefficient | 0.71 | 0.63 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.81 | |

| Adjusted value | 0.36 | 0.37 | 0.44 | 0.45 | 0.49 | |

3.4. Education

Average educational achievement for women has steadily increased, albeit with large sub-national variation. At the national level the education category went from 0.15 in 1990 to 0.41 in 2013 (Figure 1). Gender inequality in education was substantial, but diminished over time: in 1990 only four women had a primary education for very ten men; this increased to almost seven women for very ten men in 2013. Both relative and absolute educational gains have been achieved primarily in the South, with a number of northern states barely improving during the study period. In fact, the educational gap between North and South during the survey period actually widened; the non-adjusted mean difference between the two went from 0.30 to 0.46 between 1990 and 2013 and the interquartile range nearly doubled. It is particularly striking that in the most educationally impoverished northern states less than 10% of the women have basic education and literacy while in some southern states nearly 90% of the women have achieved basic education and literacy.

We did find evidence for an age cohort effect for educational attainment, indicating that the expected outcomes for young adults is better than captured by the FEMI education results. In 1990, 32% of women ages 15–30 had at least six years of education compared to 7% of women from ages 35–49 and by 2013 those numbers had climbed to 54% and 34%, respectively.

3.5. Reproductive healthcare

The reproductive healthcare category showed only small gains, rising from 0.54 in 1990 to 0.61 in 2013. The use of prenatal visits and professional care settings for childbirth is very common in the South (84% and 63% in 2013, respectively), but rarer in the North, with only 50% of women having a prenatal visit and 17% using a professional setting for childbirth in 2013. The proportion of women having children as adolescents increased in the North during the survey period, rising from 0.65 to 0.74, while in the South values were relatively steady, varying between 0.42 and 0.46.

3.6. Decision making

Female participation in decision making improved from 0.33 in 1990 to 0.46 in 2013. The data suggest that gains were mainly achieved between 2003 and 2008, jumping 0.13 in this time period. However, the values for this category for the years 1990 and 1999 were imputed, as well as the values for some individual questions in the 2003, 2008, and 2013 surveys, so there is some uncertainty regarding the trend for this variable. The gap between the North and South appears to have widened, with women's ability to make decisions holding steady in the North with an average of 0.23 during the survey period but improving from 0.41 to 0.60 between 1990 and 2013 in the South.

3.7. Access to contraception

Between 1990 and 1999 the access to contraception increased from 0.17 to 0.26. However, access to contraceptives dipped 0.12 between the 1999 and 2003 surveys and has not fully recovered since. Post-1999 gains are concentrated primarily in the South, with 44% of women having access to contraceptives in 2013 compared to only 12% of women in the North.

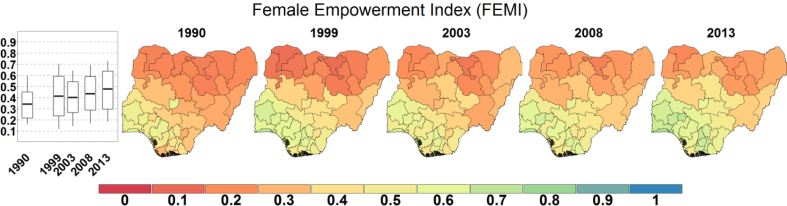

3.8. The Female Empowerment Index

The FEMI has increased significantly during the 23-year survey period. With the exception of the access to contraception category, values in 2013 are the highest they have ever been, with lower levels of violence, and higher levels of health, education, decision making, and gainful employment for women across Nigeria. The national level FEMI was 0.34 in 1990 and 0.48 in 2013. However, the state and regional variation in the FEMI was substantial for all survey years. For individual states it ranged from 0.16 to 0.62 in 1990 and from 0.19 to 0.75 in 2013. The FEMI gap between the North and South actually widened during the survey period, going from 0.25 in 1990 to 0.32 in 2013 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The Female Empowerment Index for Nigeria at the national (boxplot) and state level (maps) between 1990 and 2013, computed as the equally-weighted average of the six FEMI categories (violence against women, employment, education, reproductive healthcare, decision making, and access to contraception). Boxplots were made using state level data, but with the median (thick horizontal bar) adjusted for population size to better reflect the true national median.

While the FEMI is attractive as it provides a single number, it is interesting to consider trends in individual categories and how they contribute to changes in the FEMI. Improvements in the FEMI between 1990 and 1999 were largely driven by improved access to contraceptives in the South and improved employment in the North. From 1999-2003, there was reduced access to contraceptives in much of the country, but the FEMI did not decrease as there were gains in the other categories, particularly employment. From 2003-2008, the primary drivers of change in the FEMI were more varied, including a mix of improvements in violence, decision making, contraception, and employment. Changes between the 2008–2013 surveys came from a relatively equal mix of improvements in all six FEMI categories.

4. Discussion

There is much interest in improving the empowerment of women as illustrated by its inclusion of women's empowerment in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Better monitoring of women's empowerment can be an important step toward improving it; but this has proven to be a very difficult task, both conceptually and methodologically. There are many different possible definitions of empowerment, and it is not entirely clear which definitions to use and how to measure them. In addition, limitations in data availability have led to sub-optimal measurements of empowerment.

We have addressed some of these conceptual and methodological problems by using DHS data to develop a new index to measure women's empowerment and implement it in Nigeria at the sub-national level for five years. The FEMI captures most of the primary aspects the empowerment measures developed by the UNDP (political empowerment is the only exception) and adds women-specific contraception measures, violence against women, decision making, and additional women's reproductive healthcare variables. Thus, the FEMI captures more aspects of female empowerment and for a wider socioeconomic strata than has been achieved with previous indices. Creating a sub-national index is a logical next step in the measurement of women's empowerment, and we have shown the importance of doing so given the wide variation in empowerment among Nigerian states.

DHS data is available for 90 predominantly lower income and lower-middle income countries, and the index could be applied to many of these countries as well. Sexual and physical violence data reported by DHS were far off other figures reported in the literature. Because the data were relatively uniform across the country, simple solutions like linear adjustments based on other reported figures were not possible. Improving the physical and sexual violence response accuracy in the DHS empowerment module as well as making the raw response data available for all surveys would be a great step forward in determining the past and current status of empowerment.

DHS sample sizes are quite large, and data quality was generally sufficient to support statements about the spatial and temporal variation in woman's empowerment. The 1990 and 1999 surveys had low sample sizes compared to the latter three surveys, but there were clear and persistent spatial and temporal patterns at the state level, illustrated by the high spatial autocorrelation. The relatively low spatial autocorrelation for employment may be a reflection of noise due to the relatively small sample size or because there truly is a weaker spatial relationship for this category. Additional research is needed to determine which is the case in order to inform future index revisions.

Certain DHS questions, including age at first marriage, age at first child, educational level, and literacy rates are highly sensitive to age. Responses to these questions were consistently more positive for younger women compared to older women. It is possible that accuracy could be affected if age cohorts are not similar in size across time. While this does not appear to be the case for Nigeria (Table 1), it could be an issue when computing FEMI in other countries. In our case, the average age of the respondents was 28–29 years old. If the average ages were markedly different in another country, age-corrected values could be computed. For example, if large age variation is detected, one could, instead of using the average across age groups, use all data to estimate the values for a particular age group (e.g. 28–29 years old).

Imputing data for missing questions and categories was essential to provide a full picture of women's empowerment across all survey years, especially the 1990 and 1999 surveys, but doing so introduces uncertainty and should be therefore be undertaken carefully. In this case, quality of the imputed data were variable. While RandomForest models for education were almost perfect (R2 = 0.98), this was not the case for all questions, especially for questions where there was a reduced sample size, such as the employment category, which is only available for married women. Because of the strong temporal trends in the data, survey year was the most important predictor variable for almost all imputations.

Newer DHS surveys also have several interesting questions regarding women's experience of emotional violence. Unfortunately, in the case of Nigeria, these questions were only asked for the 2008 and 2013 surveys and our Random Forest imputation model was very poor for these questions (R2 = 0.12), so we did not include them in FEMI. Additional research on finding better predictor variables for these categories might improve the modeling results and allow inclusion of emotional violence, which would also improve the breadth of FEMI.

Developing an index like the FEMI is a balancing act between creating an ideal measure that captures as many aspects of empowerment as possible while making practical decisions of what to include and exclude based on data availability and quality. We have shown that the DHS surveys are an important source of multidimensional data suitable for analyzing women's empowerment. DHS surveys are very similar between countries and over time, although some empowerment-related questions are more commonly available in more recent surveys due to the creation and inclusion of the empowerment module in 1999. However, it should be noted that the module does not appear to be widely utilized until the mid-2000s, as was the case for Nigeria.

It is not possible to directly externally validate the quality of the FEMI for Nigeria as there are no alternative estimates for sub-national data. Ewerling et al. (2017) compare their national level DHS results with the GDI and found reasonable correspondence despite the fact that the GDI uses different data and has well-known flaws, suggesting that computations of these indices may be robust against differences in methods and data used. Establishing whether this is indeed the case is an important area of future research, among other things by computing the FEMI for other countries and comparing the national level results with the GDI and GII.

We believe that FEMI is likely to be superior to the GDI and GII on logical grounds. The GDI uses only the formal sector of earned income, which limits its ability to track the progress of women in lower socioeconomic strata. GDI is not a freestanding measure – it effectively subtracts from the Human Development Index (HDI) based on gender inequality. Thus it is neither independent of overall development, nor an index that focuses on overall women's empowerment beyond gender gaps. The GII and GDI share the same flaw of failing to adequately account for women of lower socioeconomic strata. They only include the formal employment sector rather than both the formal and informal sectors, which we have overcome by including in-kind and a mix of paid and in-kind work. One third of the GII consists of formal labor force participation, and another sixth consists of parliamentary representation. While important, parliamentary representation is unlikely to be applicable to most women, especially the most poor and disadvantaged.

To calculate the FEMI, we computed the unweighted mean of the six empowerment categories. It is possible to compute a weighted mean or to use different methods to combine the categories. Our goal was to develop a simple index that provides a measure which can directly be compared between studies. However, the FEMI categories are inherently important, independent of the index, and we have made these available by state to allow for the examination of individual categories or the use of alternate weighting schemes (see Appendix 1).

5. Conclusion

The FEMI is a new sub-national index of women's empowerment using widely-available DHS data that has the potential to be used in many developing countries across the world. Prior work on examining female empowerment has been exclusively at the national level. The sub-national nature of FEMI demonstrates how national-only measures can actually obscure important sub-national differences in empowerment, as is the case for Nigeria. The country has strong state and regional variation across multiple aspects of women's empowerment, illustrating the importance of considering state and regional variation in addition to national variation. Our implementation makes a strong case for the need for sub-national reporting of women's empowerment in addition to national measures.

We have demonstrated that women's empowerment is much lower in the North than in the South of Nigeria. In education, decision making, and access to prenatal care, the situation in the North worsened even as it improved in the South. Even in categories where the North and South both show improvement, the North still lags greatly behind. Targeted interventions may be needed to improve women's empowerment in the North so that all women in Nigeria have the levels of access to education, contraception, and the other opportunities enjoyed by women in the South.

At the national level, the FEMI improved considerably between 1990 and 2013. Despite the stark regional differences, women are better educated, have more opportunities for gainful employment, access to better reproductive healthcare, more decision making power in their families, and are encountering lower rates of physical and sexual violence. In contrast, access to contraception has gone down at the national level; more research is needed to understand why this is the case.

While using DHS data does have some inherent limitations such as the necessity of estimating data for earlier surveys, the ability to examine women's empowerment sub-nationally is a major strength. FEMI and its individual category results represent large improvements in what is known about women's empowerment in Nigeria in terms of scope, within-country variation, and change over time.

We implemented the FEMI with data from Nigeria and the methodology used could easily be extended to other countries. This would allow for between-country comparison as well as within-country variation. While different measures will continue to be computed based on needs and perceptions of women's empowerment, FEMI's sub-national contribution is unique and its wide scope of categories broaden its utility relative to existing measures.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Erica M Rettig: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Stephen Fick: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Robert J Hijmans: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (USA) under grant OPP1099842 and by the Feed the Future Sustainable Intensification Innovation Lab (SIIL) under the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) grant AID-OOA-L-14-00006.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

Appendix 1

References

- Antai Diddy E., Antai Justina B. Attitudes of women toward intimate partner violence: a study of rural women in Nigeria. Rural Rem. Health. 2008;8(3):996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beteta Cueva, Hanny “What is missing in measures of women’s empowerment? J. Hum. Dev. 2006;7(2):221–241. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley Sarah E.K., Croft Trevor N. 2017. Revised Unmet Need - General Variable.Do.https://dhsprogram.com/topics/upload/Stata-Revised-unmet-need-variable-general.zip [Google Scholar]

- Bradley Sarah E.K., Croft Trevor N., Fishel Joy D. 2012. Revising Unmet Need for Family Planning: DHS Analytical Studies No. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman Leo E.O. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001;45(1):1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ewerling F., Lynch J.W., Victora C.G., van Eerdewijk A., Tyszler M., D Barros A.J. The SWPER index for women's empowerment in Africa: development and validation of an index based on survey data. The Lancet Global Health. 2017;5:PE916–E9237. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30292-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawole Olufunmilayo I., Aderonmu Adedibu L., Fawole Adeniran O. Intimate partner abuse: wife beating among civil servants in Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr. J. Reprod. Health. 2005;9(2):54–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gakidou Emmanuela, Cowling Krycia, Lozano Rafael, Murray Christopher J.L. Increased educational attainment and its effect on child mortality in 175 countries between 1970 and 2009: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2010;376(9745):959–974. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61257-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates Melinda French. Putting women and girls at the center of development. Science. 2014;345(6202):1273–1275. doi: 10.1126/science.1258882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaye Amie. Measuring Key Disparities in Human Development: the Gender Inequality Index. Geneva. 2010. http://hdr.undp.org/en/reports/global/hdr2010/papers/HDRP_2010_46.pdf

- Gottschalk N. Uganda: early marriage as a form of sexual violence. Forced Migr. Rev. 2007;(27):3. http://www.fmreview.org/FMRpdfs/FMR27/34.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Hirway Indira, Mahadevia Darshini. Critique of gender development index: towards an alternative. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 1996;31(43):WS87–96. www.jstor.org/stable/4404713 [Google Scholar]

- ICF International [Distributer] 1992–2014. Demographic and Health Surveys for Nigeria (Various) [Google Scholar]

- Ilika Amobi L., Okonkwo Prosper I., Prosper Adogu. Intimate partner violence among women of childbearing age in a primary health care centre in Nigeria. Afr. J. Reprod. Health. 2002;6(3):53. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3583257?origin=crossref [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klasen Stephan. “UNDP’s gender-related measures: some conceptual problems and possible solutions. J. Hum. Dev. 2006;7(2):243–274. [Google Scholar]

- Knippenberg Rudolf. Neonatal survival series 3 systematic scaling up of neonatal care: what will it take in the reality of countries? Lancet. 2005;(March):23–35. [Google Scholar]

- Nour Nawal M. Health consequences of child marriage in Africa. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006;12(11):1644–1649. doi: 10.3201/eid1211.060510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okemgbo C.N., Omideyi A.K., Odimegwu C.O. Prevalence, patterns and correlates of domestic violence in selected Igbo communities of Imo state, Nigeria. Afr. J. Reprod. Health. 2002;6(2):101–114. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3583136 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okenwa Leah E., Stephen Lawoko, Jansson Bjarne. Exposure to intimate partner violence amongst women of reproductive age in Lagos, Nigeria: prevalence and predictors. J. Fam. Violence. 2009;24(7):517–530. [Google Scholar]

- Olagbuji Biodun, Ezeanochie Michael, Ande Adedapo, Ekaete Ekop. Trends and determinants of pregnancy-related domestic violence in a referral center in southern Nigeria. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2010;108(2):101–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyediran K.A., Feyisetan B. Prevalence and contextual determinants of intimate partner violence in Nigeria. Afr. Popul. Stud. 2017;31(1):3464–3477. Supplement. [Google Scholar]

- Oyediran Kolawole Azeez, Isiugo-Abanihe Uche. Perceptions of Nigerian women on domestic violence: evidence from 2003 Nigeria demographic and health survey. Afr. J. Reprod. Health. 2005;9(2):38–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psacharopoulos George. Returns to investment in education: a global update. World Dev. 1994;22(9):1325–1343. [Google Scholar]

- UN General Assembly . Report of the Open Working Group of the General Assembly on Sustainable Development Goals. New York. 2014. 12 general assembly document A/69/970, New York. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . United Nations: 72; 2015. The Millennium Development Goals Report.https://visit.un.org/millenniumgoals/2008highlevel/pdf/MDG_Report_2008_Addendum.pdf [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Program Human development report (1990 to present) Hum. Dev. Rep. 1995: Gender Hum. Dev. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- UN Women “Take five with papa seck: getting better at gender data—why does it matter?”. 2016. https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2016/9/feature-story-take-five-with-papa-seck-on-gender-data#sthash.yIr20S5N.dpuf

- World Economic Forum . 2018 the Global Gender Gap Report. 2019. World Economic Forum.https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-gender-gap-report-2018 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1