Abstract

Purpose

In the present study, a systematic histological analysis of the glenohumeral joint capsule was conducted.

Materials and methods

12 cadaveric shoulders were examined. Inclusion criteria were: 1) intact joint capsule and 2) fixation in neutral position. The tissue samples were Elastica Hematoxylin-van-Gieson-(ElHvG) stained and diameter, quantity, and distribution patterns were analyzed.

Results

We detected a new layer (elastic boundary layer, EBL) between the synovial and fibrous membrane. The elastic fibres of the EBL differ considerably in diameter, quantity, and distribution pattern.

Conclusions

A previously undescribed layer was noticed, which we named elastic boundary layer for now.

Keywords: Shoulder, Joint capsule, Elastic fibres, Elastic boundary layer, Histology

1. Introduction

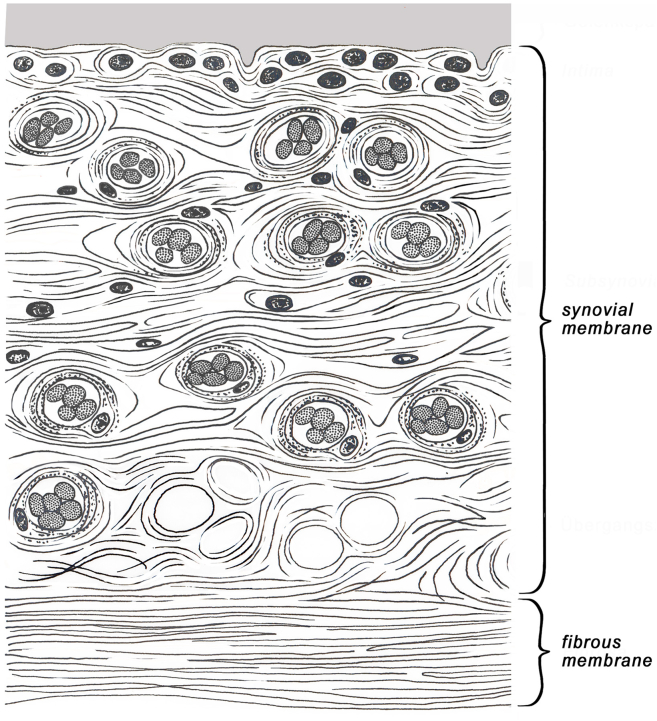

The glenohumeral joint capsule plays a critical role in shoulder stability.1 Histologically, the capsule consists of the typical structure with synovial and fibrous membrane2 (Fig. 1). The fibrous membrane is formed mainly of dense collagen type I fibre bundles, elastic fibres, vessels and nerve fibres with mechanoreceptors.3,4 The internal synovial membrane is formed by a 20–40 μm thick covering layer with 1–3 cell rows of synovial type A and B cells and by an up to 5 mm thick subsynovial layer which consists among to others, of connective tissue, vessels, adipozytes, elastic fibres, and immune cells.5, 6, 7, 8 In addition, the glenohumeral joint capsule is reinforced by the coracohumeral and glenohumeral ligaments.9,10

Fig. 1.

Classic graphic representation of the shoulder joint capsule with synovial. membrane and fibrous membrane.

Elastic fibres consist of an amorphous core of elastin and closely associated microfibrils that are composed of fibrillin and microfibrillar associated glycoprotein.11, 12, 13 They can occur singly or in networked structures and usually have a diameter of 0.2–1.5 μm.14 Due to their structure, elastic fibres have the potential to stretch strongly and return to their original position without energy consumption.15, 16, 17

So far, it is known that elastic fibres contribute, among other things, to the mechanical stability of intervertebral discs and collateral ligaments of the knee joint.

Rodeo et al. reported that the glenohumeral capsule from patients with shoulder instability had increases in collagen fibril diameters and elastin fibre content when compared with normal shoulder capsule which is possibly a remodeling of the capsule to prevent recurrent joint dislocation.18 Despite the ubiquitous occurrence of elastic fibres only very few studies had been undertake to date to clarify their role in degenerative pathologies.19 One reason for this neglect is the lack of knowledge of the anatomical basis on elastic systems in certain topographic regions like arthrons.

However, to date there is no detailed investigation of the glenohumueral joint capsule focusing on the arrangement and distribution of elastic fibres in the different tissue layers.

Therefore in the present study, a systematic histological analysis of the glenohumueral joint capsule on the diameter, quantity and distribution pattern of elastic fibres was conducted to provide further evidence.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Extraction of tissue samples

12 cadaveric shoulders, fixed in 4% formalin (tissue concentration), from 6 body donors (mean age 81.3, SD: 7.4, range: 69–89 years) of the donor program were examined. Four tissue samples were taken from different sites of the joint capsule: 1) area of the axillar recess 2) area of the supraspinatus tendon, 3) area of the long biceps tendon and 4) area of coracohumeral ligament.

Inclusion criteria were: 1) intact joint capsule and 2) fixation of the joints in neutral position. Exclusion criteria were 1) damage of the joint capsule through preparation or previous surgical interventions, 2) implants in the shoulder region, 3) rheumatic diseases and 4) neuromuscular diseases. 11/12 shoulder joints met our criteria.

2.2. Histology

The tissue samples were processed according to the protocol described by Romeis20:

-

1

Washing of the samples under tap water for one week

-

2

Incubation in 50%, 70%, 90%, 96% and 99,5% (2x) isopropyl for 24 h each

-

3

Incubation in Roticlear® solution (Carl Roth GmBH + CoKG, Karlsruhe) for two days

-

4

Incubation in paraffin at 60 °C for 2 days and embedding in paraffin blocks

-

5

Safe and smooth sectioning to 6 μm section plates by microtome

-

6

Drying of the samples at room temperature, 37 °C and 70 °C for 30 min each

-

7

Incubation in Roticlear®, 99,5% (2x), 96% and 70% ispropyl for 5 min each

2.3. Elastica hematoxylin-van-Gieson-(ElHvG)-stain

The tissue samples were stained according to the following protocol:

-

1

Staining in Elastica-solution for 15 min

-

2

Washing under tap water

-

3

Staining in iron hematoxyline according to Weigert for 5 min

-

4

Washing under tap water and aqua dest. for 10 min

-

5

Staining in van-Gieson-solution for 1 min

-

6

Washing under tap water and aqua dest. (2x)

-

7

Incubation in 96% (2x), 100% (2x) isopropyl, Xylene and Eukitt® (Merck, Darmstadt)

2.4. Evaluation of elastic fibres

From each tissue sample 4–5 images were documented. The images were shot in 400x magnification, the size of each image was 0.369–0.461 mm2 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Histology of the shoulder joint capulse: with synovial membrane (A), boundary layer (B) and fibrous membrane (C). The boundary layer shows primary. curled elastic fibers with direction (category 3). Magnification 400x.

To analyze the diameter of elastic fibres, the fibres were divided into 4 mean categories and measured using a visual analogue scale: 1) “thin fibres” (<0.75 μm), 2) “thick fibres” (0.75–2 μm), 3) “membranous fibres” (>2 μm) and 4) “diffuse staining” (no differentiation possible).

The quantity of elastic fibres was classified into 5 mean categories: 1) not visible (no fibres), 2) isolated fibres (<10 fibres), 3) few fibres (10–29 fibres), 4) many fibres (30–100 fibres) and 5) very many fibres (>100 fibres).

The distribution patterns of elastic fibres were also subdivided into 5 mean categories: 1) parallel fibres, 2) crossed fibres, 3) curled fibres with orientation, 4) curled fibres without orientation and 5) cross-cut fibres. In all cases (diameter, quantity and distribution pattern), there are also possible combinations inside the group. The histological analysis was conducted by the second author.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Results are presented as mean or median ± SD (standard deviation). Our data was examined for normal distribution. Statistical significance was calculated by the following tests: test according to Dunn-Bonferroni, chi-squared-test, test according to Kruskal-Wallis, and Mann–Whitney rank sum test, using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 25 and Microsoft Excel. P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

2.6. Approval of the ethics committee

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee, with the terms according to the Best Practices of Donor Programs of the AACA, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The local ethics committee approved this study (Registration Number 4883).

3. Results

3.1. New layer between synovial and fibrous membrane

In our investigations we were able to detect a new layer between the synovial and fibrous membrane, which has not been described in the literature. The new layer (elastic boundary layer) is rich in vessels and adipozytes. Furthermore, this elastic boundary layer differs significantly in diameter, quantity and distribution pattern of elastic fibres in comparison to the synovial and fibrous membrane (see below) (Fig. 2, Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

New graphic representation of the shoulder joint capsule. The elastic fibers are shown in orange. Due to the special arrangement of the elastic fibers (significant. more primary curled fibers with direction), a new layer (borderline layer) can be defined. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

3.2. Diameter, quantity and distribution pattern of elastic fibres in the joint capsule

Our examinations of the diameter of elastic fibres in the shoulder joint capsule showed a significant increase in diameter in the elastic boundary layer (mean value: 1.6) in comparison to the synovial membrane (mean value: 1.36, p = 0.029) and fibrous membrane (mean value: 1.3, p = 0.001) (Fig. 4). Membranous fibres or combinations between the different categories play only a subordinate role.

Fig. 4.

Diameter of elastic fibers in synovial membrane, 348 borderline layer and. fibrous membrane, n = 11, significance: * = p ≤ 0.05, ** = p ≤ 0.001.

The analysis on quantity of elastic fibres showed a significant difference between synovial membrane (mean value: 0.77, category 1) and elastic boundary layer (mean value: 1.88, category 2, p = 0.0001) respectively the fibrous membrane (mean value: 1.92, category 2, p = 0.0001). A significant difference between elastic boundary layer and fibrous membrane was not seen (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Quantity of elastic fibers in synovial membrane, borderline layer and fibrous 352 membrane, n = 11, significance: *** = p ≤ 0.0001.

The examination of the distribution pattern of the elastic fibres showed primary parallel fibres in synovial and fibrous membrane (mean value: 1.73 and 1.31) with significant more fibres with parallel orientation (category 1) in the fibrous membrane (p = 0.026). In the elastic boundary layer, we found primary curled fibres with orientation (category 3) (mean value 2.41). The distribution pattern of the synovial membrane and fibrous membrane showed a significant increase respectively decrease of curled fibres with orientation (p = 0.003 and p = 0.0001) compared to the elastic boundary layer (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Distribution pattern of elastic fibers in synovial membrane, borderline layer. and fibrous membrane, n = 11, significance: * = p ≤ 0.05, ** = p ≤ 0.001, *** = p ≤ 0.0001.

4. Discussion

The systematic histological examination of the exact arrangement and distribution of elastic fibres of the shoulder joint capsule in the present study revealed a new and previously unknown layer between the synovial and fibrous membrane. This, what we called “elastic boundary layer” differs significantly in structure and distribution of elastic fibres in comparison to synovial and fibrous membrane and cannot be clearly assigned to any membrane. So far, due to the structure with loose connective tissue, the layer has been assigned to the synovial membrane. However, the examination of the elastic fibres showed a different structure compared to the synovial membrane. The synovial membrane consists mainly of isolated thin parallel elastic fibres, whereas the elastic boundary layer consists of mainly orientated curled elastic fibres and a larger diameter. In regard to the quantity of elastic fibres, the elastic boundary layer would be associated rather with the fibrous membrane. Both show a similar amount of elastic fibres. However, they significantly differ in the distribution and diameter. The exact structure and organization of the layers could indicate that the elastic fibres play a role in the stability and strengthening of the shoulder joint capsule. These hypotheses confirm the study of Rodeo et al.. Here, immunhistochemical examinations for collagen and elastic fibres showed a significant higher density of elastic fibres in unidirectional and multidirectional shoulder instability compared to shoulders without pathologies.18 Moreover, the density of the fibres was significantly increased after revision surgery. In conclusion, the possibility of an adaptation of the elastic fibres to increased mechanical stress due to the dislocation of the humeral head was suspected in respect to repeated capsular deformation. This hypothesis is also confirmed by other studies where mechanical stress is answered by an increased stimulation of elastic fibews respectively in case of significant degradation of elastic fibres in reduction the original form.21, 22, 23 In their study Smith et al. degradated elastic fibres of annuli fibrosi by enzymatic techniques. Subsequent mechanical tests showed a significant reduction in both the initial modulus and the ultimate modulus. The influence of other collagenous could be excluded by special techniques. The examiners concluded that elastic fibres play an unique role in the properties of the annulus fibrosus. The formation of individually organized systems of elastic fibres in the capsule layers in our study points toward these hypotheses that elastic fibres have a meaning in the biomechanics of the joint capsule and thus in the stabilization of the entire joint. This knowledge can be helpful to improve the restoration of capsule integrity after capsule injuries during surgical procedures by selecting suitable capsule seams. Previous studies showed, that elastic fibres can adapt themselves. Future studies should evaluate the distribution pattern of elastic fibres in the three distinct layers of the capsule in different pathologic conditions of the shoulder joint.

The inner arrangement of collagenous fibres, i.e. traction solid layer of the capsule, is very sophisticated and needs recovery after stress rearrangement.24 This could be managed by the elastic boundary layer which concentrates restoring forces close to the layer of collagenous fibres. Besides a physiological role in restoration of the collagenous layer under tensile forces, there might be an impact on shoulder pathology. Castagna et al. reported in a pilot study an age depended relationship of the morphology of elastic fibres in patients with glenohumeral instability. Elastic fibres also may contribute to capsule shrinking, degeneration, or healing processes.

5. Conclusion

Based on the distribution pattern, a previously undescribed layer was noticed, which was called elastic boundary layer by us. We showed that elastic fibres in the layers of the glenohumeral joint capsule form a distinct layered system, which might play an important role in the biomechanics of the capsule and thus in the stabilization of the entire joint. Further cadaver- and in vivo studies have to show the role of this layer in different pathological situations.

CRediT author statement

Hannes Kubo: Writing- Original draft preparation, Supervision, Formal analysis. Eva Gatzlik: Data curation, Investigation. Martin Hufeland, Markus Konieczny and David Latz: Data curation, Formal analysis. Hakan Pilge and Timm Filler: Writing - review & editing.

Ethical review committee statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee, with the terms according to the Best Practices of Donor Programs of the AACA, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The local ethics committee approved this study (Registration Number 4883).

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Contributor Information

Hannes Kubo, Email: hannes.kubo@med.uni-duesseldorf.de.

Eva Gatzlik, Email: eva.gatzlik@gmail.com.

Martin Hufeland, Email: martin.hufeland@med.uni-duesseldorf.de.

Markus Konieczny, Email: markus.konieczny@med.uni-duesseldorf.de.

David Latz, Email: david.latz@med.uni-duesseldorf.de.

Hakan Pilge, Email: pilge@orthopaedicum-muc.de.

Timm Filler, Email: timm.filler@uni-duesseldorf.de.

References

- 1.Kaltsas D.S. Comparative study of the properties of the shoulder joint capsule with those of other joint capsules. Clin Orthop. 1983;(173):20–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zilles K., Tillmann B.N. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2010. Anatomie.http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-540-69483-0 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen M.S., Schimmel D.R., Masuda K., Hastings H., Muehleman C. Structural and biochemical evaluation of the elbow capsule after trauma. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(4):484–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Savalle W.P., Weijs W.A., James J., Everts V. Elastic and collagenous fibers in the temporomandibular joint capsule of the rabbit and their functional relevance. Anat Rec. 1990;227(2):159–166. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092270204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haywood L., Walsh D.A. Vasculature of the normal and arthritic synovial joint. Histol Histopathol. 2001;16(1):277–284. doi: 10.14670/HH-16.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith M.D. The normal synovium. Open Rheumatol J. 2011;5:100–106. doi: 10.2174/1874312901105010100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith M.D., Barg E., Weedon H. Microarchitecture and protective mechanisms in synovial tissue from clinically and arthroscopically normal knee joints. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(4):303–307. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.4.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simkin P.A. Physiology of normal and abnormal synovium. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1991;21(3):179–183. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(91)90007-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bey M.J., Hunter S.A., Kilambi N., Butler D.L., Lindenfeld T.N. Structural and mechanical properties of the glenohumeral joint posterior capsule. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(2):201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gohlke F., Daum P., Bushe C. Über die stabilisierende Funktion der Kapsel des Glenohumeralgelenkes. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1994;132:112–119. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1039828. 02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Debelle L., Tamburro A.M. Elastin: molecular description and function. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1999;31(2):261–272. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(98)00098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montes G.S. Structural biology of the fibres of the collagenous and elastic systems. Cell Biol Int. 1996;20(1):15–27. doi: 10.1006/cbir.1996.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenlee T.K., Ross R., Hartman J.L. The fine structure of elastic fibers. J Cell Biol. 1966;30(1):59–71. doi: 10.1083/jcb.30.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ushiki T. Collagen fibers, reticular fibers and elastic fibers. A comprehensive understanding from a morphological viewpoint. Arch Histol Cytol. 2002;65(2):109–126. doi: 10.1679/aohc.65.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown R.E., Butler J.P., Rogers R.A., Leith D.E. Mechanical connections between elastin and collagen. Connect Tissue Res. 1994;30(4):295–308. doi: 10.3109/03008209409015044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kielty C.M., Sherratt M.J., Shuttleworth C.A. Elastic fibres. J Cell Sci. 2002;115(Pt 14):2817–2828. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.14.2817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sherratt M.J. Tissue elasticity and the ageing elastic fibre. Age Dordr Neth. 2009;31(4):305–325. doi: 10.1007/s11357-009-9103-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodeo S.A., Suzuki K., Yamauchi M., Bhargava M., Warren R.F. Analysis of collagen and elastic fibers in shoulder capsule in patients with shoulder instability. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26(5):634–643. doi: 10.1177/03635465980260050701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith K.D., Clegg P.D., Innes J.F., Comerford E.J. Elastin content is high in the canine cruciate ligament and is associated with degeneration. Vet J Lond Engl. 1997;199(1):169–174. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.11.002. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romeis - Mikroskopische Technik | Maria Mulisch. http://www.springer.com/de/book/9783642551895 Springer, Accessed.

- 21.Oxlund H., Manschot J., Viidik A. The role of elastin in the mechanical properties of skin. J Biomech. 1988;21(3):213–218. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(88)90172-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shimada K., Takeshige N., Moriyama H., Miyauchi Y., Shimada S., Fujimaki E. Immunohistochemical study of extracellular matrices and elastic fibers in a human sternoclavicular joint. Okajimas Folia Anat Jpn. 1997;74(5):171–179. doi: 10.2535/ofaj1936.74.5_171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith L.J., Byers S., Costi J.J., Fazzalari N.L. Elastic fibers enhance the mechanical integrity of the human lumbar anulus fibrosus in the radial direction. Ann Biomed Eng. 2008;36(2):214–223. doi: 10.1007/s10439-007-9421-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gohlke F., Essigkrug B., Schmitz F. The pattern of the collagen fiber bundles of the capsule of the glenohumeral joint. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1994;3(3):111–128. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(09)80090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]