Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate safety and feasibility in a first in human trial of direct MRI-guided prostate biopsy using a novel robotic device.

Methods:

MrBot is an MRI-safe robotic device constructed entirely of nonconductive, nonmetallic, and nonmagnetic materials, developed by our group. A safety and feasibility clinical trial was designed to assess the safety and feasibility of direct MRI-guided biopsy with MrBot and determine its targeting accuracy. Men with elevated PSA, prior negative prostate biopsy and cancer suspicious region (CSR) on MRI were enrolled in the study. Biopsies targeting CSR’s in addition to sextant locations were performed.

Results:

Five men underwent biopsy with MrBot. Two men required Foley catheter insertion after the procedure, with no other complications or adverse events. Even though this was not a study designed to detect prostate cancer, biopsies confirmed the presence of clinically significant cancer in 2 patients. On a total of 30 biopsy sites, the robot achieved an MRI-based targeting accuracy of 2.55mm and precision of 1.59 mm normal to the needle, with no trajectory corrections and no unsuccessful attempts to target a site.

Conclusions:

Robot-assisted MRI-guided prostate biopsy appears safe and feasible. This study confirms that clinically significant prostate cancer (≥5mm radius, 0.5 cm3) depicted in MRI may be accurately targeted. Direct confirmation of needle placement in the CSR may present an advantage over fusion-based technology, and gives more confidence in a negative biopsy result. Additional study is warranted to evaluate the efficacy of this approach.

Keywords: MRI-Safe, robot, prostate biopsy, transperineal, magnetic resonance imaging

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is most commonly detected as a result of prostate-specific antigen (PSA)-screening with subsequent transrectal ultrasound (TRUS)-guided biopsy. Although PSA screening has led to reduced prostate-cancer specific mortality1, concerns exist regarding both overdiagnosis of indolent disease 2 and underdiagnosis of high-grade disease.3 Additionally, TRUS-guided biopsy is associated with both low sensitivity and a high false negative rate.4, 5

While traditional biopsy relies on PCa-blind, untargeted 12-core biopsies, advances in multi-parametric MRI (mpMRI) have allowed visualization of lesions within the prostate.6 Consequently, mpMRI has increasingly been adopted as a tool for PCa detection7, staging,8 and more recently has been used for biopsy targeting. MRI-fusion biopsy, a technology in which pre-acquired MRI is registered (fused) with TRUS, showed increased diagnosis of high-risk PCa and decreased detection of low-risk cancers.9 Results of MRI-fusion biopsy are encouraging and the technology is a substantial advance over the TRUS alone. While studies have evaluated correlation of fusion biopsy findings with whole gland radical prostatectomy specimens9, the accuracy of fusion biopsy in targeting cancer-suspicious regions (CSR) in real time is unknown. Therefore, it remains unclear if this technology is sufficiently accurate to consistently target significant PCa lesions.

MRI-fusion is subject to several technical limitations. Gland shape compression, temporal differences and patient position differences between the pre-acquired MRI and interventional TRUS can cause registration misalignment.10 In MRI-fusions systems, confirmation of needle placement is confirmed with ultrasound in the absence of real-time MRI. These limitations may contribute to biopsy targeting errors, but it is impossible to know if or when this happens as there is no real-time visual confirmation of needle placement with MRI.

An alternative that circumvents fusion is direct MRI-guided biopsy, in which CSR targeting, needle guidance and post-biopsy targeting confirmation is verified under MRI. MRI-guided in-bore biopsies are challenging secondary to limited access to the patient within the bore of the scanner, and manual instrument handling, adjustments of the needle guide angulation and needle insertion depth which are prone to imprecisions.11, 12 A solution to this problem is the use of robotic devices designed to operate in the space and environmental restrictions inside the MR scanner. In this pilot study we evaluate a direct, in-gantry transperineal prostate biopsy using a novel robotic device (MrBot)13–17 for safety and feasibility.

Methods

Study Design

This study was a first in human, safety and feasibility study of the MrBot investigational device for direct MRI-guided transperineal prostate biopsy. Technical details regarding the robotic system, regulatory clearance, and image-guidance have been previously published18The device was approved by the FDA for the study and our institutional review board approved an initial safety and feasibility study limited to five patients. Inclusion criteria were men between age 35 and 75, a prior negative 12 core biopsy, and at least one of the following features: (1) PSA ≥5ng/ml and prostate volume ≤50cc, (2) PSA density ≥0.2ng/ml/cc, (3) percent free PSA ≤10%, (4) PSA velocity >0.5ng/ml/year, or (5) high grade prostate intraepithelial neoplasia or atypia on a previous biopsy. Patients were excluded if they had bleeding problems, MRI-incompatible implants, previous rectal surgery, or previous pelvic irradiation. Even though this safety and feasibility study was not designed for clinical significance, patients with CSR on independently available multiparametric MRI (mpMRI) were selected for the study to increase the likelihood of visualizing CSR at the time of the intervention. CSRs were scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1-highly likely benign, 2-likely benign, 3 –indeterminate, 4-likely malignant, 5 highly likely malignant), as previously described.19, 20 The trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02080052).

MRI protocol

On the day of the biopsy, the patient underwent a shorter MRI with T2-weighted fast spin-echo images: TR/TE = 3170/80 msec, slice thickness 4 mm, interslice gap 0-1 mm, matrix 384 x 288, FOV 40 x 40 cm, frequency direction anteroposterior, number of excitations = 2, and “distortion correction” parameter ON. CSRs were identified and used for targeting in addition to sextant locations.

Device and Procedure

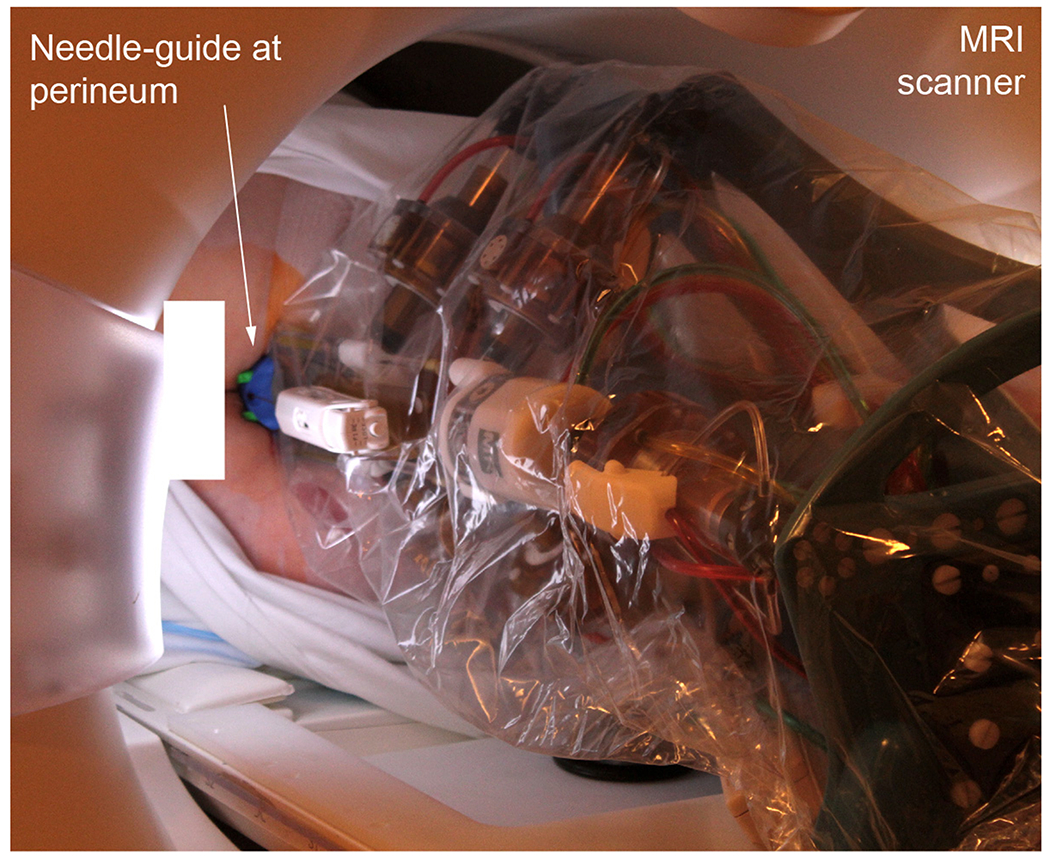

MrBot is an MRI-Safe 21 robotic device constructed of nonmagnetic and dielectric materials, and powered by a pneumatic step motor.16 The robot is electricity free, using air for actuation and light for the sensors. The device mounts on the MRI table beside the patient while in left lateral decubitus position.13, 14 (Figure 1). To prevent patient motion, for this safety and feasibility trial the patient was placed under general anesthesia. A small (1cm) perineal skin incision was made. To gain room for the robot, the patient was positioned with the back as close as possible to the MR bore. The robot was placed on the table so that the nozzle of the needle-guide was placed superficially through the incision. The robot was secured with vacuum-powered suction cups on the table, at an angle that pointed the needle-guide approximately towards the prostate.

Figure 1:

The MrBot robot is positioned in the MRI gantry next to patient in the left lateral decubitus position

A 3 Telsa whole body scanner with 60 cm bore size (TrioTim, Siemens Medical Solutions, Malvern, PA) was used with surface body matrix coil wrapped over the pelvis and optional endorectal eCoil™ (Medrad, Warrendale, PA). Images were acquired and the robot was registered to the image space based on registration markers built in the robot structure. Biopsy target points including the CSR were defined in MRI. One by one, the robot positioned and oriented the needle-guide straight on target. The depth of needle insertion was also automatically set by adjusting the location of a depth limiter to the point selected in the image corresponding to the center of the core slot of the needle.

Two types of needles were used in the study, both manufactured by Invivo, Pewaukee,WI: 9896-032-02861 (11528), 18Gax150mm Semi-Automatic Biopsy Gun and 9896-032-05281, 18Gax175mm Fully Automatic Biopsy Gun. A transperineal biopsy was performed manually through the guide up to the depth limiter. Confirmation imaging (True-FISP, fast imaging with steady-state precession) of the needle was acquired. The procedure then cycles to the next selected biopsy target.

Analysis

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the safety and feasibility of MRI-guide robot-assisted transperineal prostate biopsy. The outcome variables of the study include clinical measures such as the patient characteristics, times for several steps of the procedure (patient positioning, anesthesia, device setup, imaging, robot registration, biopsy planning, biopsy procedure), number of biopsy sites, complications, patient discomfort [1-5, 1-none], pain level [1-5, 1-none], and overall satisfaction [1-5, 1 completely satisfied] (logged at the end of the procedure and 24 hours following the procedure). Patient characteristics include the number of prior negative biopsies acquired with TRUS, the number of CRSs observed in the previously acquired MRI, and the CSR Score from the same MRI.

Outcome variables related to the operation of the robotic device include the number of unsuccessful attempts to target a site, number of trajectory corrections to target a site, and targeting errors. Targeting errors were measured in MRI as the distance between the actual biopsy core center and the target point, as a 3D vector and also in a plane normal to the needle. Accuracy and precision were calculated as usual, based on the mean and standard deviation of the respective errors.

Results

Five men underwent biopsy using MrBot. The mean age was 66.4 years (range 55-72), and the mean PSA was 22.4 ng/dl with an average prostate size of 76.6 cc. Patient characteristics and biopsy result are listed in Table 1. All patients tolerated the procedure well. Post-procedure, two men experienced acute urinary retention that required Foley catheter insertion, with no other complications and no subsequent adverse events. Both patients subsequently passed a trial of voiding 3 days after the procedure without further interventions.

Table 1:

Patient size, clinical, imaging characteristics, and biopsy result

| Size | PSA | Prostate Size [cm3] | Prior | Biopsy Result | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | AP [cm] | TV [cm] | AP+TV [cm] | Weight [Kg] | Negative Biopsies | CSR | CSR Score | |||

| 1 | 24 | 40 | 64 | 89 | 43.3 | 148 | 2 | 2 | 3 | negative |

| 2 | 21 | 35 | 56 | 68 | 29 | 47 | 2 | 1 | 4 | positive |

| 3 | 19.2 | 36.6 | 55.8 | 67 | 4.8 | 44 | 2 | 2 | 4 | positive |

| 4 | 22.5 | 38.5 | 61 | 91 | 8.9 | 42 | 1 | 1 | 3 | negative |

| 5 | 19.9 | 38.6 | 58.5 | 79 | 26 | 102 | 3 | 1 | 3 | negative |

Clinically related outcome variables are shown in Table 2. The mean number of biopsies per patient was 7.8 (median 8), and there were no unsuccessful attempts to target a site. Mean patient discomfort, pain level and overall satisfaction was 1.6, 1.2 and 1.2, respectively.

Table 2:

Outcome variables

| Mean (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Times [min] | Patient positioning and anesthesia | 70 (26) |

| Device setup | 8 (3) | |

| Imaging | 50 (18) | |

| Robot-to-image registration | 8 (6) | |

| Define biopsy locations | 6 (3) | |

| Biopsy time / site | 10 (1) | |

| Total clinical time | 208 (30) | |

| Number of biopsy sites per patient | 7.8 (1.30) | |

| Unsuccessful attempts to target a site | 0 | |

| Patient discomfort [1-5, 1-none] | 1.6 (0.55) | |

| Pain level [1-5, 1-none] | 1.2 (0.45) | |

| Overall satisfaction [1-5, 1 completely satisfied] | 1.2 (0.45) | |

The mean total clinical time for the procedure was 208 minutes, and the time decreased with each subsequent patient (Supplementary Figure 1). In case 3, the MRI scanner shut down at the beginning of the procedure for an unknown cause, adding time to the procedure.

An endorectal coil was used only on the first patient, and no endorectal coil was used in the subsequent four cases. The first case was performed with the semi-automated biopsy needle. Six biopsy sites were targeted and 3 trajectory corrections were necessary. The accuracy was 14.78 mm and precision 3.82 mm. Needle deflection from a straight path was pronounced.

For the subsequent cases the needle was changed to the fully automated type. Moreover, near the midpoint of the insertion stroke, the needle was rotated 180° about its axis to compensate for lateral deflections due to the beveled point. In the final 4 cases, the accuracy and precision of targeting over 30 biopsy sites were 2.97mm and 1.50mm, respectively in 3D and 2.55mm and 1.59mm, respectively in a plane normal to the needle, with no trajectory correction.

Biopsies confirmed the presence of clinically significant cancer in 2 patients.

Patient #2 was a 70-year-old man with a 47 cc prostate and PSA 29 ng/dl. MRI demonstrated a CSR score 4 in the right transition zone. Targeted biopsy with MrBot demonstrated Gleason 4+3=7 (Grade Group 3) PCa in 2 cores. This patient subsequently underwent radical prostatectomy that demonstrated 4+3=7 (Grade Group 3) PCa with extraprostatic extension, with negative margins (pT3N0). He had an undetectable PSA at last follow-up.

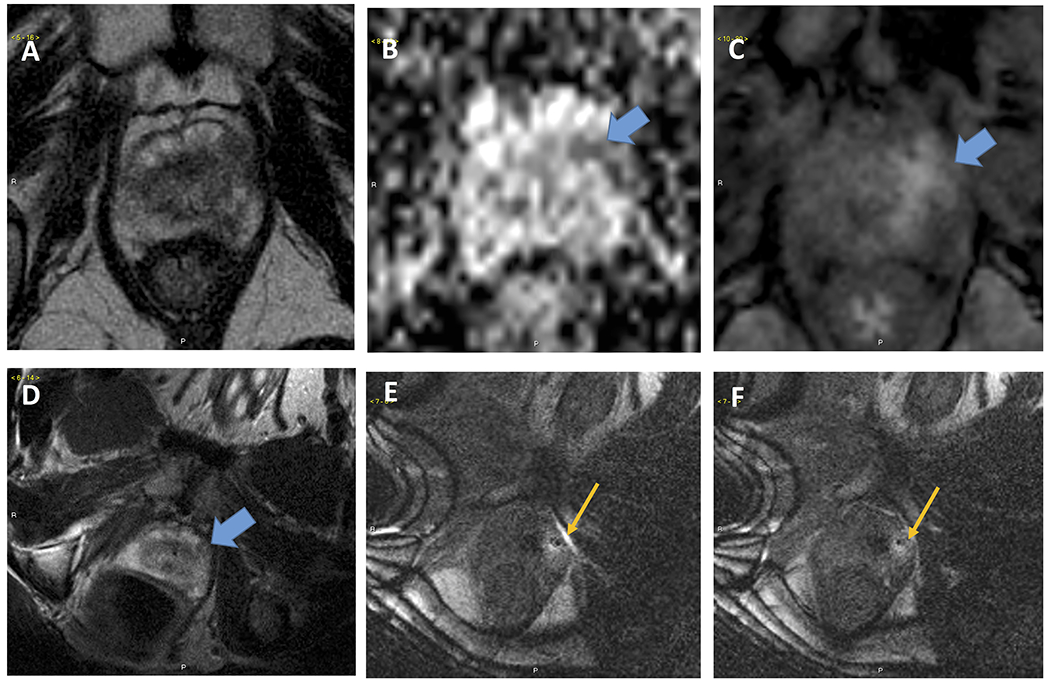

Patient #3 was a 64-year-old man with a 44 cc prostate and PSA of 4.8 ng/dl. MRI demonstrated a CSR score 4 in the left anterior apex. Targeted biopsy with MrBot demonstrated Gleason 5+4=9 (Grade Group 5) in 2 cores, Gleason 4+4=8 (Grade Group 4) PCa in an additional core, and high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia in a core. Pre-procedure mpMRI images, as well as intraprocedural targeting and confirmation images are shown in Figure 2. The patient subsequently underwent radical prostatectomy and was found to have Gleason 4+5=9 (Grade Group 5) PCa with extraprostatic extension, bilateral seminal vesicle invasion, positive margins and negative lymph nodes (pT3bN0R1). He underwent adjuvant radiotherapy with androgen deprivation, and had an undetectable PSA at last follow-up.

Figure 2:

Patient #3. Pre-biopsy images (A-C) demonstrated A.T2 weighted, B DWI-ADC and C. Dynamic contrast enhanced (DCE) sequences of a left-apical cancer suspicious regions. Intraprocedural image (D-F) demonstrate D. T2 weighted image acquired during procedure in left decubitus position, E Needle entering the prostate and F. Needle (appears as dark dot) in target lesion.

In Patient #1 needle deflections were pronounced, targeting accuracy was low, and the biopsy result was benign. He was subsequently diagnosed with a high-grade PCa in the anterior transition zone following a repeat mpMRI. He underwent radical prostatectomy revealing a dominant nodule 3+5=8 in the anterior right and left prostate base, mid, apex. He also had left anterior extraprostatic tumor extension (pT3a).

Discussion

This study was designed to evaluate the safety and feasibility of direct MRI guided robot-assisted transperineal prostate biopsy. We found that this technology is feasible and safe, with transient urinary retention as the only adverse side effect. This finding was not unsurprising, as acute urinary retention is a known complication of perineal prostate biopsy. Buskirk and colleagues reported an 11.5% rate of retention after transperineal prostate biopsy and found that number of biopsies and prostate size were predictors of retention.22, 23

The main critique of direct MRI-guided interventions so far is the lengthy procedure time.24 This technique collates several procedures that are normally done independently, including the anesthesia and the MRI which is inherently slow. By itself, the biopsy procedure time/site is on the order of 10 min. Overall, a decreasing total time trend was observable over the 5 cases, but it is unknown to what level these may be reduced with further experience and technology improvements. In this safety and feasbility study we opted for general anesthesia to reduce problems related to patent motion. A recent similar study24 reported the use of intravenous procedural sedation and lower times.

Even though mpMRI was not used during the biopsy, PCa was still sampled at biopsy based on the T2-weighted images alone. Overall, PCa was detected in two (40%) patients and missed in one (20%). The missed case was our first case when targeting errors were large and needle deflection was pronounced. Even so, this detection rate in on par with longitudinal studies of repeat biopsy after initial negative biopsy.25, 26 Ploussard and colleagues reported detection of PCa on subsequent biopsies as 16.7% after second, 16.9% after third and 12.5% after fourth biopsies.25 Similar, Gann et al found increasing number of biopsies associated with lower risk of detection, while elevated PSA levels were associated with a higher risk of detection.26

An important outcome parameter of the study is the measurement of targeting accuracy, as this is an unknown parameter with fusion methods. The robot was capable of 2.55 mm accuracy. For PCa the required accuracy is probably < 5mm, since a clinical significant tumor (0.5 cm3) has a 5mm radius if spherical. But staying within the 5mm radius is very difficult. Targeting errors include several, often cumulative components.18 In our case #1 the errors were on the order of 15 mm. A problem that many others also confronted is that needle deflection errors are sizeable.27 We have been able to cope with that by using a fully-automated biopsy needle and rotating the needle 180° about its axis near the middle of the insertion stroke.28

The achieved MRI-based targeting accuracy of 2.55 mm is novel. The most recent similar direct MRI-guided clinical trial24 was performed on a large 30-patinet population but unfortunately targeting accuracy data was not reported. This data is also missing for the fusion methods. As such, this study demonstrates that the smallest clinically significant PCa tumors may be accurately targeted.

If the largest or most identifiable CSR in MRI are the most clinically significant ones then accurate targeted biopsy will 1) reduce the randomness that yields clinically insignificant cancer detection, and 2) increase the likelihood of sampling the most advanced CSR reducing the underdiagnosis of potentially lethal cancer. Currently this is unknown. The accurate biopsy method may help validate PCa imaging methods.

Relative to fusion biopsy, which has no quality control relative to the imaging method used to identify the CSR, direct (imaged) confirmation of needle insertion in the CSR may give more confidence in a negative biopsy result. Fusion biopsy, however, is a non-disruptive advance over the standard TRUS technique, and it remains to be tested if the additional accuracy is helpful.

The main limitations of our study are its small sample size that was required by the IRB to demonstrate safety before increasing the enrollment, and the basic MRI used in this initial trial. Addtionally, as this is the initial report a new technique, there is likely a learning curve that is not yet overcome in this series. It is yet unknown if using mpMRI to guide the biopsy will increase the rate of significant PCa detection.

Conclusion

In this initial report of robot-assisted direct MRI-guided prostate biopsy, the procedure appears safe and feasible, but currently lengthy. We demonstrate that it is possible to accurately target the smallest clinically significant PCa tumor depicted in MRI. A larger efficacy study is needed to define the role of this procedure in clinical practice.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1: Composite procedure times for 5 patients undergoing prostate biopsy with MrBot

Acknowledgement:

The project described was supported by Award Number RC1EB010936 from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Under a licensing agreement between Samsung and the Johns Hopkins University, Dr. Stoianovici has received income on an invention described in this article. This arrangement has been reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.

References

- 1.Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. Screening and prostate cancer mortality: results of the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) at 13 years of follow-up. Lancet. 2014;384:2027–2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loeb S, Bjurlin MA, Nicholson J, et al. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment of prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2014;65:1046–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson IM, Ankerst DP, Chi C, et al. Operating characteristics of prostate-specific antigen in men with an initial PSA level of 3.0 ng/ml or lower. JAMA. 2005;294:66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rabbani F, Stroumbakis N, Kava BR, Cookson MS, Fair WR. Incidence and clinical significance of false-negative sextant prostate biopsies. J Urol. 1998;159:1247–1250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Terris MK. Sensitivity and specificity of sextant biopsies in the detection of prostate cancer: preliminary report. Urology. 1999;54:486–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dickinson L, Ahmed HU, Allen C, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging for the detection, localisation, and characterisation of prostate cancer: recommendations from a European consensus meeting. Eur Urol. 2011;59:477–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanimoto A, Nakashima J, Kohno H, Shinmoto H, Kuribayashi S. Prostate cancer screening: the clinical value of diffusion-weighted imaging and dynamic MR imaging in combination with T2-weighted imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;25:146–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marcus DM, Rossi PJ, Nour SG, Jani AB. The impact of multiparametric pelvic magnetic resonance imaging on risk stratification in patients with localized prostate cancer. Urology. 2014;84:132–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siddiqui MM, Rais-Bahrami S, Turkbey B, et al. Comparison of MR/ultrasound fusion-guided biopsy with ultrasound-guided biopsy for the diagnosis of prostate cancer. JAMA. 2015;313:390–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin PR, Cool DW, Romagnoli C, Fenster A, Ward AD. Magnetic resonance imaging-targeted, 3D transrectal ultrasound-guided fusion biopsy for prostate cancer: Quantifying the impact of needle delivery error on diagnosis. Med Phys. 2014;41:073504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liddell H, Jyoti R, Haxhimolla HZ. mp-MRI Prostate Characterised PIRADS 3 Lesions are Associated with a Low Risk of Clinically Significant Prostate Cancer - A Retrospective Review of 92 Biopsied PIRADS 3 Lesions. Curr Urol. 2015;8:96–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mouraviev V, Verma S, Kalyanaraman B, et al. The feasibility of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging for targeted biopsy using novel navigation systems to detect early stage prostate cancer: the preliminary experience. J Endourol. 2013;27:820–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muntener M, Patriciu A, Petrisor D, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging compatible robotic system for fully automated brachytherapy seed placement. Urology. 2006;68:1313–1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muntener M, Patriciu A, Petrisor D, et al. Transperineal prostate intervention: robot for fully automated MR imaging--system description and proof of principle in a canine model. Radiology. 2008;247:543–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patriciu A, Petrisor D, Muntener M, Mazilu D, Schar M, Stoianovici D. Automatic Brachytherapy Seed Placement under MRI Guidance. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 2007;54:1499–1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stoianovici D, Patriciu A, Petrisor D, Mazilu D, Kavoussi L. A New Type of Motor: Pneumatic Step Motor. IEEE ASME Trans Mechatron. 2007;12:98–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stoianovici D, Song D, Petrisor D, et al. “MRI Stealth” Robot for Prostate Interventions. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol 2007;16:241–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stoianovici D, Kim C, Petrisor D, et al. MR Safe Robot, FDA Clearance, Safety and Feasibility Prostate Biopsy Clinical Trial. IEEE ASME Trans Mechatron. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kitajima K, Kaji Y, Fukabori Y, Yoshida K, Suganuma N, Sugimura K. Prostate cancer detection with 3 T MRI: comparison of diffusion-weighted imaging and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI in combination with T2-weighted imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;31:625–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vargas HA, Akin O, Franiel T, et al. Diffusion-weighted endorectal MR imaging at 3 T for prostate cancer: tumor detection and assessment of aggressiveness. Radiology. 2011;259:775–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stoianovici D, Kim C, Srimathveeravalli G, et al. MRI-Safe Robot for Endorectal Prostate Biopsy. IEEE ASME Trans Mechatron. 2013;19:1289–1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buskirk SJ, Pinkstaff DM, Petrou SP, et al. Acute urinary retention after transperineal template-guided prostate biopsy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59:1360–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pinkstaff DM, Igel TC, Petrou SP, Broderick GA, Wehle MJ, Young PR. Systematic transperineal ultrasound-guided template biopsy of the prostate: three-year experience. Urology. 2005;65:735–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song SE, Tuncali K, Tokuda J, et al. Workflow Assessment of 3T MRI-guided Transperineal Targeted Prostate Biopsy using a Robotic Needle Guidance. Proc. SPIE 2014;9036. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ploussard G, Nicolaiew N, Marchand C, et al. Risk of repeat biopsy and prostate cancer detection after an initial extended negative biopsy: longitudinal follow-up from a prospective trial. BJU Int. 2013;111:988–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gann PH, Fought A, Deaton R, Catalona WJ, Vonesh E. Risk factors for prostate cancer detection after a negative biopsy: a novel multivariable longitudinal approach. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1714–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ukimura O, Desai MM, Palmer S, et al. 3-Dimensional elastic registration system of prostate biopsy location by real-time 3-dimensional transrectal ultrasound guidance with magnetic resonance/transrectal ultrasound image fusion. J Urol. 2012;187:1080–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Webster RJ, Kim JS, Cowan NJ, Chirikjian GS, Okamura AM. Nonholonomic Modeling of Needle Steering. Int J Rob Res. 2006;25:509–525. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: Composite procedure times for 5 patients undergoing prostate biopsy with MrBot