Abstract

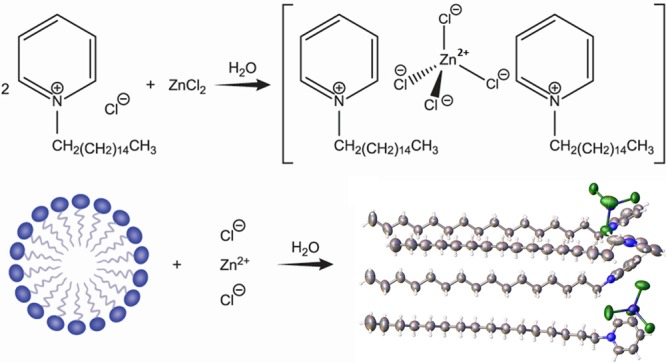

Cetylpyridinium tetrachlorozincate (referred to herein as (CP)2ZnCl4) was synthesized and its solid-state structure was elucidated via single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SC-XRD), revealing a stoichiometry of C42H76Cl4N2Zn with two cetylpyridinium (CP) cations per [ZnCl4]2– tetrahedra. Crystal structures at 100 and 298 K exhibited a zig-zag pattern with alternating alkyl chains and zinc units. The material showed potential for application as a broad-spectrum antimicrobial agent, to reduce volatile sulfur compounds (VSCs) generated by bacteria, and in the fabrication of advanced functional materials. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of (CP)2ZnCl4 was 60, 6, and 6 μg mL–1 for Salmonella enterica, Staphylococcus aureus, and Streptococcus mutans, respectively. The MIC values of (CP)2ZnCl4 were comparable to that of pure cetylpyridinium chloride (CPC), despite the fact that approximately 16% of the bactericidal CPC is replaced with bacteriostatic ZnCl2 in the structure. A modified layer-by-layer deposition technique was implemented to synthesize mesoporous silica (i.e., SBA-15) loaded with approximately 9.0 wt % CPC and 8.9 wt % Zn.

Introduction

Cetylpyridinium chloride (CPC) is a quaternary ammonium compound with broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity. Its antimicrobial properties render it useful in a variety of applications including cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and water treatment.1,2 CPC is recognized as safe for dermal and oral applications by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and is commonly known for its role in the prevention and treatment of dental plaque, gingivitis, halitosis, and calculus in oral care products.1,3−7 Zinc (Zn) is utilized in a wide array of industries including food, pharmaceuticals, energy production, material science, physiology, and organic chemistry.8−11 Existing exclusively as the divalent Zn cation, Zn is an essential nutrient for virtually all living organisms.12 However, at concentrations higher than those that are physiologically useful, Zn exhibits a bacteriostatic effect on many microorganisms.13

The antibacterial property of Zn2+ ions has been attributed to five main mechanisms: (1) the disruption of cell membrane integrity, (2) the denaturation of proteins, (3) the production of reactive oxygen species resulting in cellular damage, (4) the interaction with nucleic acids, and (5) the inactivation of iron–sulfur proteins and/or inhibition of the iron–sulfur protein maturation machinery.14−18 When CPC disrupts the microbial cell membrane, the positively charged region of CPC binds directly to the polar negatively charged phosphate groups of phospholipids while the nonpolar portion of CPC interacts with nonpolar phospholipid tails.3,19 This results in the permeability of the cell membrane, membrane depolarization, leakage of intracellular components, and ultimately death.3 Recent experiments suggest that loading quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs) into mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) yields a material with excellent antimicrobial activity and a pH-responsive controlled release of the antimicrobial drug.20

Previously, a number of studies have focused on elucidating the interaction between divalent metal (e.g., Cd, Cu, and Zn) ions and pyridine analogues; however, these studies were not successful in identifying and realizing an antibacterial technology that is viable, safe, and effective for widespread healthcare use. In 2002, Neve et al. synthesized and solved the crystal structure of [C16-Py]2[CdCl4].21 The application of the material was not evaluated or mentioned beyond its potential to be used as a liquid-crystalline precursor. Furthermore, attempts to crystallize the Zn analog were futile. Hilp et al. proposed the use of cetylpyridinium tetrachlorozincate as a titrant for analysis of anionic surfactants.22,23 In 2015, Kaur et al. synthesized (CP)2CuCl4 and (CP)CuCl3 and demonstrated that the insertion of copper into the CPC moiety enhanced the antibacterial activity as compared to pure CPC.24 Although the antimicrobial properties of copper (Cu) have long been known, the realization of the Cu–cetylpyridinium conjugate technology for healthcare applications would be extremely challenging due to the potential for blue (e.g., Cu2+) or yellow (e.g., [CP][CuCl3] or [CP]2[CuCl4]) staining associated with the d-orbital splitting of the copper ion.

The current work reports the synthesis and characterization of cetylpyridinium tetrachlorozincate as well as its application to reduce volatile sulfur compounds, as an antibacterial active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), and to fabricate advanced functional materials. Work presented suggests that cetylpyridinium tetrachlorozincate is a viable and effective antimicrobial agent to combat the global healthcare issues associated with oral and dermal disease (e.g., hospital infections, medical device biofilms, and antibiotic resistance).

Results and Discussion

Initial observation of an interaction between CPC and ZnCl2 was made while attempting to synthesize a deep eutectic solvent via anhydrous route. In particular, monohydrate CPC and anhydrous ZnCl2 powders were combined, mixed, and heated at 90 °C for 24 h. Under these conditions, a translucent, yellow-colored gel material was formed in samples with a Zn/CPC ratio of 2 and higher. The material would undergo a phase change below approximately 50 °C to form an off-white opaque solid material. To improve the homogeneity of the samples, the synthesis was repeated with the addition of 15% water. Subsequent experiments, aimed to develop an aqueous route for the synthesis, demonstrated that a sparingly water-soluble precipitate is formed upon a combination of aqueous CPC and ZnCl2 solutions above a certain threshold concentration. The solubility of the precipitate in water was <1 wt % at room temperature. The precipitate was collected, washed with copious amounts of water, and recrystallized from acetone to yield a single crystal adequate for single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SC-XRD) analysis. Dynamic scanning calorimetry (DSC) experiments (Figure S1) demonstrated a ∼20 °C reduction in the onset temperature of the endothermic melting peak in the synthesized material as compared to pure CPC. These results are consistent with the observed phase transition below approximately 50 °C in the gel samples synthesized via anhydrous route.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy were used to confirm complex formation prior to SC-XRD analyses and therefore referred to as the CPC–Zn material. The XPS results (Figures S2 and S3) indicate that there is a slight shift in the N+ peak for the CPC–Zn (402.2 eV) material as compared to the CPC (401.8 eV) reference. This may indicate that the electronic environment around the cationic N in the CPC part of the sample has changed as compared to that in CPC alone. It is noteworthy that anhydrous ZnCl2 cannot be easily analyzed by conventional XPS and FTIR due to its hygroscopic properties.

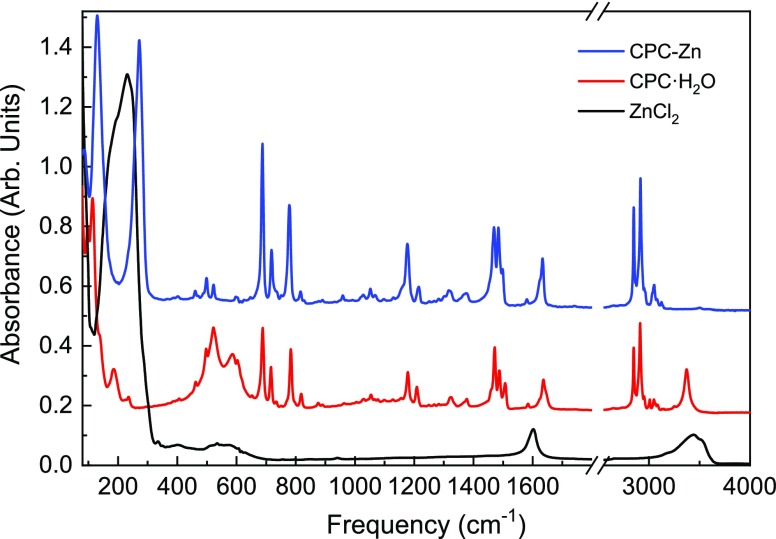

The FTIR spectra of CPC·H2O, ZnCl2, and as-synthesized CPC–Zn material are shown in Figure 1. The spectrum of the CPC–Zn sample clearly shows the fingerprint of the cetylpyridinium, confirming its presence in the sample. A close inspection of the spectrum demonstrates, however, that the bands of cetylpyridinium in the CPC–Zn material do not match the pure CPC·H2O compound. The majority of the bands related to C–H, CH2, C–C, C=C, and C=N stretching and bending vibrations of cetylpyridinium display shifted peak positions as compared to the CPC·H2O raw material.25,26 The ν(OH) peak at 3372 cm–1 as well as another broad H2O-related band near 550 cm–1 seen in the CPC·H2O starting compound have also disappeared in the presence of Zn. Furthermore, a distinguishable new peak at 272 cm–1 is evident in the CPC–Zn sample, likely originating from the ZnCl-related vibration. Taken together, the FTIR data indicate that the interaction of cetylpyridinium chloride with ZnCl2 resulted in the formation of a new complex.

Figure 1.

Infrared absorption spectrum of the synthesized CPC–Zn material in comparison to the CPC·H2O and ZnCl2 precursors. The spectra are offset for clarity.

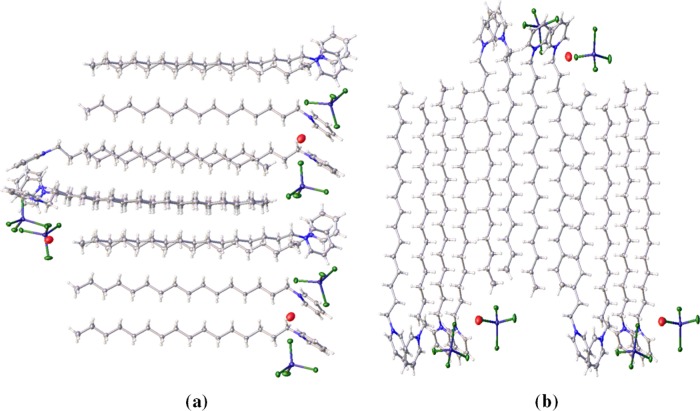

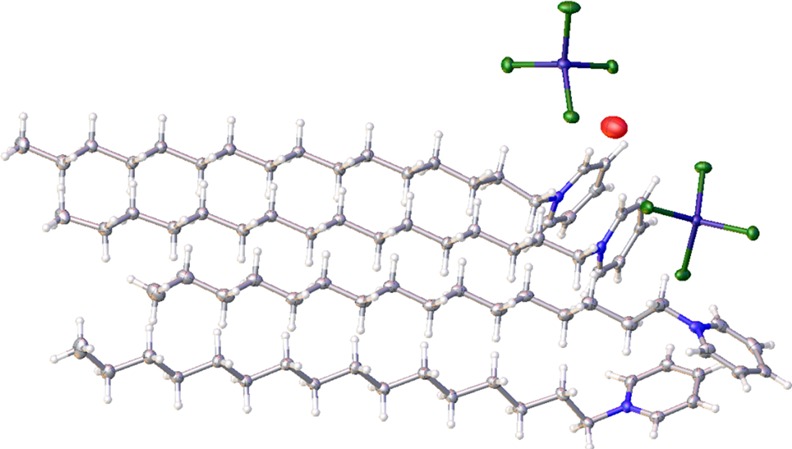

To elucidate the structure of the complex and analyze the interactions involved, SC-XRD analysis was carried out which shows that the coordination complex crystallizes in the orthorhombic Pbca space group. The structural formula can be described as [(C21H38N)2][ZnCl4], or (CP)2ZnCl4 for short, whereby two ZnCl42– units are present in close contact with four cetylpyridinium units by C–H–Cl interactions (Figure 2). The packing behavior is depicted in Figure 3. As seen from the structure, the alkyl chain units and the Zn units pack in a zig-zag manner, with each unit present at alternating ends.

Figure 2.

Structure of [(C21H38N)2][ZnCl4], illustrating carbon (gray), hydrogen (white), nitrogen (blue), zinc (purple), chloride (green), and oxygen (red) atoms.

Figure 3.

Packing of [(C21H38N)2][ZnCl4] along (a) (110) plane and (b) (100) plane.

The crystals contain a disordered solvent that was modeled as a H2O molecule (atom O1). It was not possible to locate the hydrogen atoms of H2O. The occupancy of the H2O molecule is ∼0.25 and it is not present in the crystals collected at room temperature (Figure S5). There is a structural change with the increase in temperature and concomitant loss of the solvent H2O molecule. The distance between the Zn(II) centers (Zn01–Zn02) increases from 8.73 Å (at 100 K) to 9.05 Å (at 298 K). However, the packing behavior at room temperature remains similar in a zig-zag manner (Figure S5).

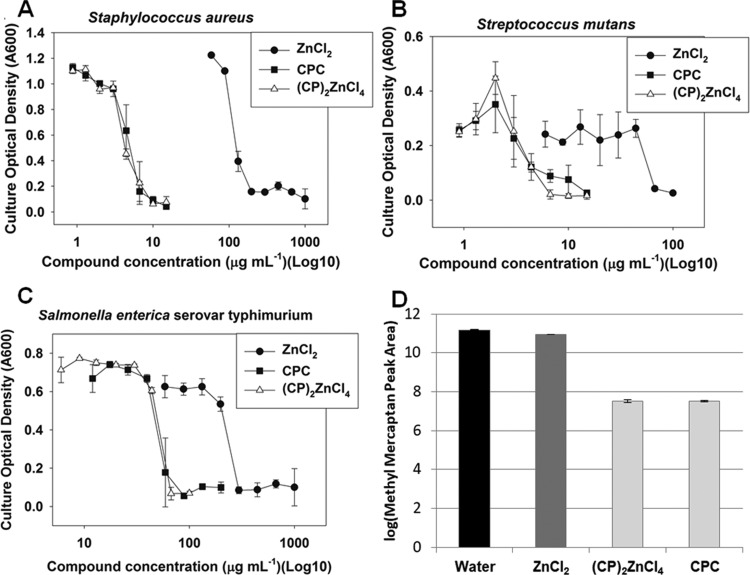

The effect of ZnCl2, (CP)2ZnCl4, and CPC on in vitro bacteria-generated volatile sulfur compounds (VSC), conducted by methyl mercaptan gas chromatography (GC) headspace measurement, is illustrated in Figure 4D. Statistical grouping, calculated using the Tukey method and a 95.0% confidence interval, indicates that CPC and (CP)2ZnCl4 exhibit parity efficacy for malodor-causing VSCs.27 However, at the measured concentration, ZnCl2 exhibits a weak VSC reduction effect as compared to CPC and (CP)2ZnCl4. The elemental composition of the powders evaluated for VSC reduction is shown in Table S3. The concentration of ZnCl2 (i.e., 16.22 wt %) in the (CP)2ZnCl4 is in decent agreement with the theoretical value (i.e., 16.70 wt %), which implies adequate purity of the sample as a result of the acetone extraction process.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus (A), Streptococcus mutans (B), and Salmonella enterica (C) with ZnCl2, CPC, and (CP)2ZnCl4. VSC reduction efficacy (D) of methyl mercaptan with color shading corresponding to the statistical group (Table S4).

The ability of CPC, Zn, and (CP)2ZnCl4 to inhibit the growth of bacterial pathogens (i.e., Staphylococcus aureus LAC, S. mutans, and S. enterica Serovar typhimurium) was examined. S. aureus LAC is a Gram-positive community-associated methicillin-resistant CA-MRSA strain and a representative strain of the USA300 clone, which is a leading cause of skin and soft tissue infections in North America.28,39S. mutans is also Gram positive and the leading causes of dental caries.29S. enterica Serovar typhimurium is Gram negative and a primary enteric pathogen affecting humans.30,40

The minimal inhibitory concentrations of CPC, Zn, and (CP)2ZnCl4 were determined in liquid culture after static growth. All of the three bacteria displayed typical dose–responses to the compounds utilized (Figure 4A–C). The MICs for Zn for S. aureus, S. enterica, and S. mutans were approximately 200, 300, and 65 μg mL–1, respectively. The MICs of (CP)2ZnCl4 for S. aureus, S. enterica, and S. mutans were 6, 60, and 6 μg mL–1, respectively. The MICs for CPC were similar to those for (CP)2ZnCl4 in the case of S. aureus and S. enterica. In the case of S. mutans, a slight improvement in the antimicrobial activity was demonstrated for (CP)2ZnCl4; however, the results did not reach statistical significance.

A previous work demonstrated that the utilization of MSNs as drug delivery vehicles for QACs yields a material with a pH-responsive controlled drug release as well as excellent antimicrobial activity.20 Herein, the feasibility of incorporating (CP)2ZnCl4 into such drug delivery systems (DDSs), where the surface of MSNs can be further modified to impart selectivity or other advantages, was explored.31 The material where (CP)2ZnCl4 was loaded into SBA-15 MSNs is referred to as CPC–Zn@SBA-15 henceforth due to a certain amount of uncertainty whether all CPC–Zn moieties within the MSNs are in fact (CP)2ZnCl4. Actually, the elemental composition suggests an excess of Zn, which is likely chemisorbed to the silanol groups. Bulk elemental composition measurements of CPC–Zn@SBA-15 were conducted using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) for CPC (9.0 wt %) and Zn (8.9 wt %), respectively. XPS analysis was conducted on mesoporous SBA-15, CPC@SBA-15, and CPC–Zn@SBA-15 to probe the elemental composition near the surface of the MSNs. Calcined SBA-15 is consistent with the composition of silica with a surface that is essentially free (1.1 wt % C) from organic contamination. The N+/Cl ratio (1.29) of the CPC@SBA-15 sample suggests that a portion of the cetylpyridinium cations has been adsorbed onto the negative silanol groups of silica. The N+ binding energy is shifted slightly relative to the CPC reference, while the Cl binding energy is significantly shifted relative to CPC. This implies that both N+ and Cl are in different chemical bonding environments on the silica surface, compared to bulk CPC. The surface of the CPC–Zn@SBA-15 material exhibited 3.36 wt % Zn, 1.01 wt % CPC, and a Zn/CPC ratio of 3.33. The Zn/CPC ratio indicates that (CP)2ZnCl4 is present on the surface with excess ZnCl2. Since the sample was washed with water after preparation, it is possible that the (CP)2ZnCl4 recrystallized on the surface or dissolved into its ionic constituents and precipitated onto the surface of MSNs.

As discussed above, ICP-OES, TGA, and XPS analyses demonstrate significant amounts of cetylpyridinium and Zn in the CPC–Zn@SBA-15 sample. FTIR was further used to investigate the presence of (CP)2ZnCl4 within the silica framework. Figure S9 shows the spectrum of the CPC–Zn@SBA-15 sample in comparison to the CPC@SBA-15 control and the SBA-15 mesoporous silica. SBA-15 displays a typical silica spectrum with asymmetric and symmetric ν(Si–O) vibrations near 1060 and 800 cm–1, respectively, nonbridging ν(Si–O–) stretching vibration and/or ν(Si–OH) vibration of silanol groups near 955 cm–1, and δ(O–Si–O) bending modes around 440 cm–1. The absorption spectra of CPC–Zn@SBA-15 and CPC@SBA-15 support the presence of cetylpyridinium in both samples as evident from its characteristic vibrations near 1500 cm–1 region as well as near the ν(C–H) stretching band region where two peaks around 2855 and 2925 cm–1 corresponding to symmetric and asymmetric ν(CH2) vibrations are observed.34 Importantly, in addition to cetylpyridinium bands, the CPC–Zn@SBA-15 sample exhibits two distinct peaks near 115 and 295 cm–1, in line with the pure (CP)2ZnCl4 profile that displays two strong bands below 300 cm–1 (Figure 1). This finding suggests the presence of the (CP)2ZnCl4 complex on the silica surface. Note, the peak positions of cetylpyridinium and (CP)2ZnCl4 incorporated into silica are shifted as compared to their bulk constituents. The latter may be attributed to adsorption and/or confinement effects.

Conclusions

A novel CPC complex, cetylpyridinium tetrachlorozincate, was synthesized and unambiguously characterized via single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SC-XRD) measurements, indicating a stoichiometry of C42H76Cl4N2Zn with two cetylpyridinium cations per [ZnCl4]2– tetrahedra. The material was evaluated and shows promising characteristics for application as a broad-spectrum antimicrobial agent, to reduce volatile sulfur compounds (VSCs) generated by bacteria, and in the synthesis of advanced functional materials. VSC experiments and antimicrobial assays demonstrate that (CP)2ZnCl4 exhibits at least parity efficacy to pure CPC while comprising approximately 16% of the significantly less efficacious and expensive zinc chloride material. An advanced functional material was prepared by successfully loading (CP)2ZnCl4 into SBA-15, which is a promising candidate for a highly efficient drug delivery system (DDS) for stimulated-release antimicrobial applications.20,35 This new technology paves the way for the development of next generation and highly efficacious healthcare treatments with potentially reduced risk of exacerbating the problem of antibiotic resistance.

Experimental Section

Synthesis of (CP)2ZnCl4

Reagent-grade anhydrous zinc chloride (ZnCl2) and cetylpyridinium chloride monohydrate were supplied by Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). All materials were used as-is without further purification. The synthesis entailed preparation of fresh 25 wt % CPC and 75 wt % zinc chloride solutions in deionized water. Subsequently, the ZnCl2 solution was added dropwise to the CPC solution under magnetic stirring. Vacuum filtration and drying of the precipitate yielded an off-white solid, which was further purified using acetone extraction. A single crystal was obtained by recrystallizing from acetone.

Characterization

X-ray photoemission spectroscopy (XPS) analysis was carried out using a PHI 5000 VersaProbe II scanning XPS microprobe instrument with a monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source (1486.6 eV) and 200 μm beam diameter. PHI MultiPak software was used for subsequent data analysis. Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were collected using a Bruker Vertex 70 FTIR spectrometer (Bruker Optics, Billerica, MA) equipped with a GladiATR diamond ATR accessory (Pike Technologies, Madison, WI). The spectral range was 80–4000 cm–1 and a resolution of 4 cm–1 was used. All measurements were carried out at room temperature, using as-prepared powder samples, without any additional sample preparation procedures. The single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SC-XRD) data were collected using Bruker D8 Venture PHOTON 100 CMOS system equipped with a Cu Kα INCOATEC ImuS microfocus source (λ = 1.54178 Å). Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) data were collected at room temperature using a Bruker D8 Advance θ–2θ diffractometer with copper radiation (Cu Kα, λ = 1.5406 Å) and a secondary monochromator operating at 40 kV and 40 mA, whereby samples were measured in the 2θ range of 2 to 40° at 0.5 s/step and a step size of 0.02°. Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXRD) patterns were obtained by using a Bruker Vantec-500 area detector and a Bruker FR571 rotating-anode X-ray generator operating at 40 kV and 50 mA. The diffraction system was equipped with a 3-circle Azlan goniometer, but the sample was not moved during X-ray data collection. The system used 0.25 mm pinhole collimation and a Rigaku Osmic parallel-mode (e.g., primary beam dispersion less than 0.01° in 2θ) mirror monochromator (Cu Kα, λ = 1.5418 Å). Data were collected at room temperature (∼20 °C) with a sample to detector distance of 26.25 cm. Spatial calibration and flood-field correction for the area detector were performed at this distance prior to data collection. The 2048 × 2048 pixel images were collected at the fixed detector (2θ) angle of 50° for 600 s with ω step of 0.00°. For the intensity versus 2θ plot, a 0.02° step, bin-normalized χ integration was performed on the general area detector diffraction system (GADDS) frame image. Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area and porosity measurements of the SBA-15 mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) were evaluated using a Surface Area and Porosity Analyzer (Gemini VII, Micromeritics).36 Samples were outgassed at 100 °C overnight under a constant flow of N2. Subsequent adsorption–desorption measurements were done at 77 K. Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) analysis was used to determine pore size distribution.37 Volatile sulfur compound measurements and antimicrobial assays are described in detail in the Supporting Information.38−41 (Table 1)38−4138−41

Table 1. Porosimetry Results and SAXRD Data.

| sample | BET surface area (m2/g) | pore width (Å) | pore wall thickness (Å) | 2θ | crystal sizea (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBA-15 | 627 | 48 | 18 | 1.328 | 77 |

| CPC@SBA-15 | 153 | 45 | |||

| CPC–Zn@SBA-15 | 90 | 43 | 1.311 | 66 |

Synthesis of SBA-15

Pluronic P123, 34% hydrochloric acid, and tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) were supplied by BASF (Ludwigshafen, Germany), Avantor (Allentown, PA), and Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), respectively. All materials were used as received without further purification. Santa Barbara Amorphous (SBA-15)-type material was synthesized according to conventional methods. Specifically, 4 g of pluronic P123 was mixed with 104 mL of water and 24 mL of concentrated hydrochloric acid. To this clear solution, 8.53 g of TEOS was added dropwise and subsequently stirred at 40 °C for 24 h. The resulting white powder was filtered, washed with copious amounts of deionized water, and dried at 50 °C overnight. Calcination of the as-synthesized SBA-15 was conducted in air at 550 °C for 6 h with 10 °C/min. Cetylpyridinium chloride tetrachlorozincate was incorporated into the SBA-15 framework via a modified immersion layer-by-layer deposition technique.42 After outgassing the SBA-15 at 100 °C for 2 h under vacuum, 800 mg of the powder was added to 100 g of 10 wt % aqueous CPC solution with subsequent magnetic stirring for over 1 h to allow diffusion throughout the porous framework. The CPC-containing SBA-15 was centrifuged, filtered, and washed with 150 mL of deionized water. Finally, the powder was washed with 100 g of 10 wt % ZnCl2 aqueous solution, washed with 150 mL of deionized water, and dried at 40 °C under vacuum for several days. It is noteworthy that the utilization of higher concentrations of CPC and ZnCl2 solutions failed to yield homogeneous CPC–Zn@SBA-15 powders. SBA-15 was chosen as the porous framework since its pore width can easily accommodate a CPC molecule.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Thomas Emge and Dr. Chi-yuan Cheng for their assistance in X-ray diffraction and nuclear magnetic resonance, respectively. The Boyd lab is funded by NIAID award 1R01AI139100-01 from the National Institutes of Health.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c00131.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through the contributions of all authors.

NIAID award 1R01AI139100-01 from the National Institutes of Health.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ash M.; Ash I.. Handbook of Preservatives; Synapse Information Resources, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Imai H.; Kita F.; Ikesugi S.; Abe M.; Sogabe S.; Nishimura-Danjobara Y.; Miura H.; Oyama Y. Cetylpyridinium chloride at sublethal levels increases the susceptibility of rat thymic lymphocytes to oxidative stress. Chemosphere 2017, 170, 118–123. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oral health care drug products for over-the-counter human use; antigingivitis/antiplaque drug products; establishment of a monograph; proposed rules. Fed. Regist. 2003, 68, 32247–32287. [Google Scholar]

- Sreenivasan P. K.; Haraszthy V. I.; Zambon J. J. Antimicrobial efficacy of 0.05% cetylpyridinium chloride mouthrinses. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 56, 14–20. 10.1111/lam.12008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Ling J.-Q.; Wu C. D. Cetylpyridinium chloride suppresses gene expression associated with halitosis. Arch. Oral Biol. 2013, 58, 1686–1691. 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt J.; Ramji N.; Gibb R.; Dunavent J.; Flood J.; Barnes J. Antibacterial and antiplaque effects of a novel, alcohol-free oral rinse with cetylpyridinium chloride. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2005, 6, 001–009. 10.5005/jcdp-6-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahardjo A.; Ramadhani A.; Adiatman M.; Wimardhani Y. S.; Maharani D. A. Efficacy of Mouth Rinse Formulation Based On Cetyl Pyridinium Chloride in the Control of Plaque as an Early Onset of Dental Calculus Built Up. J. Int. Dent. Med. 2016, 9, 184–188. [Google Scholar]

- Crans D. C.; Meade T. J. Preface for the forum on metals in medicine and health: new opportunities and approaches to improving health. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 12181–12183. 10.1021/ic402341n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin D. P.; Hann Z. S.; Cohen S. M. Metallo-protein-inhibitor binding: human carbonic anhydrase II as a model for probing metal-ligand interactions in a metalloprotein active site. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 12207–12215. 10.1021/ic400295f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X.-F.; Neumann H. Zinc-Catalyzed Organic Synthesis: C-C, C-N, C-O Bond Formation Reactions. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2012, 354, 3141–3160. 10.1002/adsc.201200547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mainar A. R.; Iruin E.; Colmenares L. C.; Kvasha A.; de Meatza I.; Bengoechea M.; Leonet O.; Boyano I.; Zhang Z.; Blazquez J. A. An overview of progress in electrolytes for secondary zinc-air batteries and other storage systems based on zinc. J. Energy Storage 2018, 15, 304–328. 10.1016/j.est.2017.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L.; Terwilliger A.; Maresso A. W. Iron and zinc exploitation during bacterial pathogenesis. Metallomics 2015, 7, 1541–1554. 10.1039/C5MT00170F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrangsu P.; Rensing C.; Helmann J. D. Metal homeostasis and resistance in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 338–350. 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanić V.; Dimitrijević S.; Antić-Stanković J.; Mitrić M.; Jokić B.; Plećaš I. B.; Raičević S. Synthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activity of copper and zinc-doped hydroxyapatite nanopowders. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2010, 256, 6083–6089. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2010.03.124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Qin X.; Wang B.; Xu G.; Qin Z.; Wang J.; Wu L.; Ju X.; Bose D. D.; Qiu F.; Zhou H.; Zou Z. Zinc oxide nanoparticles harness autophagy to induce cell death in lung epithelial cells. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e2954 10.1038/cddis.2017.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquet J.; Chevalier Y.; Pelletier J.; Couval E.; Bouvier D.; Bolzinger M.-A. The contribution of zinc ions to the antimicrobial activity of zinc oxide. Colloids Surf., A 2014, 457, 263–274. 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2014.05.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Ren X.; Fan B.; Huang Z.; Wang W.; Zhou H.; Lou Z.; Ding H.; Lyu J.; Tan G. Zinc Toxicity and Iron-Sulfur Cluster Biogenesis in Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85, e01967-18 10.1128/AEM.01967-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F. F.; Imlay J. A. Silver(I), Mercury(II), Cadmium(II), and Zinc(II) Target Exposed Enzymic Iron-Sulfur Clusters when They Toxify Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 3614–3621. 10.1128/AEM.07368-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrigler V.; Kogej K.; Majhenc J.; Svetina S. Interaction of cetylpyridinium chloride with giant lipid vesicles. Langmuir 2005, 21, 7653–7661. 10.1021/la050028u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubovoy V.; Ganti A.; Zhang T.; Al-Tameemi H.; Cerezo J. D.; Boyd J. M.; Asefa T. One-Pot Hydrothermal Synthesis of Benzalkonium-Templated Mesostructured Silica Antibacterial Agents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 13534–13537. 10.1021/jacs.8b04843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neve F.; Francescangeli O.; Crispini A. Crystal architecture and mesophase structure of long-chain N-alkylpyridinium tetrachlorometallates. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2002, 338, 51–58. 10.1016/S0020-1693(02)00976-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hilp M.; Zembatova S. Cetylpyridinium tetrachlorozincate as standard for tenside titration. Analytical methods with 1,3-dibromo-5,5-dimethylhydantoin (DBH) in respect to environmental and economical concern, part 19. Die Pharm. 2004, 59, 615–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilp M. Determination of anionactive tensides using cetylpyridinium tetrachlorozincate as titrant. Analytical methods in respect to environmental and economical concern, part 20. Die Pharm. 2004, 59, 676–677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur G.; Kumar S.; Dilbaghi N.; Bhanjana G.; Guru S. K.; Bhushan S.; Jaglan S.; Hassan P. A.; Aswal V. K. Hybrid surfactants decorated with copper ions: aggregation behavior, antimicrobial activity and anti-proliferative effect. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 23961–23970. 10.1039/C6CP03070J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelmboldt V. O.; Anisimov V. Y.; Bevz N. Y.; Georgiyants V. A. Development of methods for identification of cetylpyridinium hexafluorosilicate. Pharma Chem. 2016, 8, 169–173. [Google Scholar]

- Cook D. Vibrational Spectra of Pyridinium Salts. Can. J. Chem. 1961, 39, 2009–2024. 10.1139/v61-271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tukey J. W. Comparing Individual Means in the Analysis of Variance. Biometrics 1949, 5, 99–114. 10.2307/3001913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planet P. J. Life After USA300: The Rise and Fall of a Superbug. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 215, S71–S77. 10.1093/infdis/jiw444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loesche W. J. Role of Streptococcus mutans in human dental decay. Microbiol. Rev. 1986, 50, 353. 10.1128/MMBR.50.4.353-380.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fàbrega A.; Vila J. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium skills to succeed in the host: virulence and regulation. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 26, 308–341. 10.1128/CMR.00066-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.; Barnes J. C.; Bosoy A.; Stoddart J. F.; Zink J. I. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles in biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 2590–2605. 10.1039/c1cs15246g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer P. Bestimmung der Größe und der inneren Struktur von Kolloidteilchen mittels Röntgenstrahlen. Nachr. Ges. Wiss. Gottingen 1918, 26, 98–100. [Google Scholar]

- Langford J. I.; Wilson A. J. C. Scherrer after sixty years: A survey and some new results in the determination of crystallite size. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1978, 11, 102–113. 10.1107/S0021889878012844. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kung K. H. S.; Hayes K. F. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic study of the adsorption of cetyltrimethylammonium bromide and cetylpyridinium chloride on silica. Langmuir 1993, 9, 263–267. 10.1021/la00025a050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P.; Huang S.; Kong D.; Lin J.; Fu H. Luminescence functionalization of SBA-15 by YVO4:Eu3+ as a novel drug delivery system. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 3203–3211. 10.1021/ic0622959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunauer S.; Emmett P. H.; Teller E. Adsorption of Gases in Multimolecular Layers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1938, 60, 309–319. 10.1021/ja01269a023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett E. P.; Joyner L. G.; Halenda P. P. The Determination of Pore Volume and Area Distributions in Porous Substances. I. Computations from Nitrogen Isotherms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951, 73, 373–380. 10.1021/ja01145a126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yaegaki K.; Sanada K. Volatile sulfur compounds in mouth air from clinically healthy subjects and patients with periodontal disease. J. Periodontal Res. 1992, 27, 233–238. 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1992.tb01673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts C. A.; Al-Tameemi H. M.; Mashruwala A. A.; Rosario-Cruz Z.; Chauhan U.; Sause W. E.; Torres V. J.; Belden W. J.; Boyd J. M. The Suf Iron-Sulfur Cluster Biosynthetic System Is Essential in Staphylococcus aureus, and Decreased Suf Function Results in Global Metabolic Defects and Reduced Survival in Human Neutrophils. Infect. Immun. 2017, 85, e00100-17 10.1128/IAI.00100-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd J. M.; Teoh W. P.; Downs D. M. Decreased Transport Restores Growth of a Salmonella enterica Mutant on Tricarballylate. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 576–583. 10.1128/JB.05988-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically; Approved Standard, 9th ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson J. J.; Björnmalm M.; Caruso F. Technology-driven layer-by-layer assembly of nanofilms. Science 2015, 348, aaa2491 10.1126/science.aaa2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.