Abstract

In this study, an economic, sustainable, and green synthesis method of multiporous carbons from agricultural waste, water caltrop shell (denoted as WCS), was presented. To prepare the WCS biochar, the dried WCS was first carbonized to a microporous carbon with a surface area of around 230 m2 g–1 by using a top-lit-updraft method. Then, the microporous WCS biochar was directly mixed with an appropriate amount of ZnO nanoparticles and KOH as activating agents via a solvent-free physical blending route. After further activation at 900 °C, the resulted carbons possess both micropores and mesopores that were named as WCS multiporous carbons. The carbon yield of the prepared WCS multiporous carbons with high surface area in the range of 1175–1537 m2 g–1 is up to 50%. Furthermore, the micropore/mesopore surface area ratio can be simply tuned by controlling the ZnO content. For supercapacitor applications, the as-prepared WCS multiporous carbon electrodes showed high specific capacitance (128 F g–1 at 5 mV s–1) with a good retention rate at 500 mV s–1 scan rate (>60% compared to the capacitance at 5 mV s–1) and low Ohmic resistance in a 1.0 M LiClO4/PC electrolyte. In addition to the ZnO nanoparticles, CaCO3 nanoparticles with low environmental impact were also used to prepare the WCS multiporous carbons. The assembled supercapacitors also demonstrate high specific capacitance (102 F g–1 at 5 mV s–1) and good retention rate (∼70%).

1. Introduction

During the last decades, electrochemical double-layer capacitors, also named as supercapacitors, are energy storage devices that store the electrical energy in the interface between the charged surface of the electrode and the electrolyte solution.1,2 The supercapacitors have become noticeable because of their excellent cycle ability, high power density, and high charge/discharge rate performance compared to batteries.3 Although supercapacitors provide higher power in the same volume, they are not able to store the same amount of charge as batteries do. This makes supercapacitors suitable for those applications where power burst is needed, but high energy storage is not required.4 However, the limitation of its low energy density increases both the volume and cost of the device. Because of their low pore volume, the commercially available microporous carbons (pore size < 2 nm) are not very attractive.5 Therefore, it is a key issue to design a nanostructured porous carbon with pore properties specifically tailored for the supercapacitor application.6

Nowadays, porous carbon materials are widely utilized as electrode materials for supercapacitors owing to their low cost, excellent cycle stability, and easy manufacturing.7 Among them, multiporous carbons with three-dimensional mesoporous/microporous structures have become popular in recent years.8 Multiporous carbons have high potential in applications such as fuel cells, hydrogen storage devices, dye adsorption, and energy storage devices.9 Many methods have been used for the preparation of porous carbon materials, including catalytic activation, polymer blend carbonization, organic aerogel carbonization, and nanocasting.10,11 Nanocasting involves using various templates (colloids or mesoporous silica), which has proven to be particularly efficient.12 However, the removal of silica requires the toxic hydrofluoric acid, which renders the complex and nonenvironment-friendly process. Consequently, recent studies have investigated the feasibility for synthesizing porous carbons using nanoparticles as templates, for example, magnesium and calcium salts, such as magnesium acetate,13 calcium citrate,14 and calcium carbonate.15 These methods yield carbons with mesopores ranging from 2 to 20 nm. However, they usually use either sucrose or formaldehyde resin as a carbon precursor. Sucrose requires acid to catalyze polymerization, while formaldehyde resin produces tar during pyrolysis.16 Thus, finding more suitable carbon precursors is still required. Furthermore, these traditional synthesis procedures are complicated, expensive, time-consuming, and toxic. Hence, they cannot be commercialized. Development of simple low-cost strategies for the synthesis of multiporous carbons remains a significant challenge.

Previously, our group has used ZnO nanoparticles as hard templates to prepare mesoporous carbons by using petroleum pitch as the carbon precursor.17 The effects of the carbonization temperature and ZnO/pitch weight ratio on the physical properties of the multiporous carbons were studied in detail. These results showed that the specific surface area and pore volume can be easily improved by adjusting the ZnO/pitch ratio. Although industrial residual petroleum pitch shows good potential as the carbon precursor, we still tried to find other cheap and natural carbon precursors. For the sustainable purpose, biochar derived from agriculture waste is an alternative because of its rich abundance and availability. Recently, activated carbons have gained great interest for their utilization as supercapacitor electrodes because they can be readily prepared from cheap biomass residues and wastes.18

In Guantian District, Tainan, Taiwan, the annual yield of water caltrop is around 3400 tons. For storage and sale, farmers and merchants peel off the shell from water caltrop. Because of the high lignin content in the water caltrop shell (denoted as WCS), it takes about 7.79 million NT dollars to deal with the discarded shells every year. In practice, the lignin in the WCS can be converted into carbons after pyrolysis. Thus, WCS has been carbonized already to biochar at Guantian District by using a top-lit-updraft (TLUD) method via a suitable carbonization furnace.19 To increase the value of the WCS biochar, introducing meso-/micropore surface area to improve the accessibility and absorption capacity of the WCS biochar. In this paper, we provided a simple synthetic method by directly blending the WCS biochar with inorganic ZnO or CaCO3 nanoparticles and activating agents (KOH) to introduce the mesopores and micropores into the WCS biochar after high-temperature pyrolysis. The electrochemical properties of the WCS multiporous carbons for supercapacitors in an organic electrolyte were evaluated in this study.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Using WCS as the Carbon Precursor

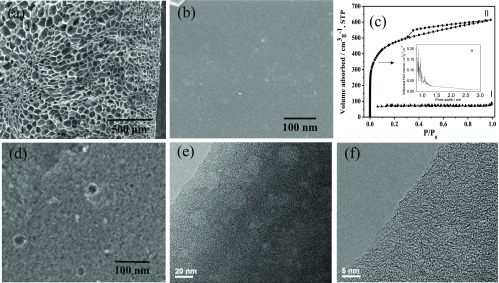

WCS was previously carbonized to biochar in a TLUD carbonization furnace at Guantian District, Tainan, Taiwan (see Supporting Information, Figure S1). After washing with an appropriate amount of H2O to remove the inorganic residuals in the WCS biochar, the physical properties of the biochar were analyzed. The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image shows that the WCS biochar exhibits many macropores (the pore size is about 30–60 μm) (Figure 1a). However, as can be seen in the SEM image (Figure 1b), a smooth surface of WCS biochar presents no micropores even at high magnification. The N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of the WCS biochar show type I isotherm with a specific surface area up to 230 m2 g–1 (Figure 1c, curve I). This indicates a mainly microporous structure (pore size < 2 nm).

Figure 1.

(a,b) SEM images of the WCS biochar; (c) N2 sorption isotherms of the WCS biochar (I) and the WCS multiporous carbon (II); the inset shows a pore size distribution curve (Horváth–Kawazoe model) for curve II; and (d) SEM and (e,f) HR-TEM images of the WCS multiporous carbon.

To introduce mesopores, 20 nm ZnO nanoparticles were used as the activating agent (Figure S2). The surface area of the resulted porous carbon is 1537 m2 g–1 when the weight ratio of WCS biochar/ZnO/KOH is 1.0:2.0:0.80 (Figure 1c, curve II). Compared to the WCS biochar, the SEM image of the WCS multiporous carbon clearly exhibits a porous texture with pore size approximately equal to 20 nm. Moreover, the high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM) images presented in Figure 1e,f show that the WCS multiporous carbon has both mesopores and micropores. The detailed textural properties of the WCS multiporous carbons synthesized with different compositions are listed in Table 1. The thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) curve (Figure S3) shows that the WCS multiporous carbons exhibit good thermal stability even at 500 °C and the inorganic residual is less than 3 wt %. In brief, these results show that the WCS biochar can be activated by ZnO nanoparticles and KOH to produce high surface area multiporous carbons with yield up to 48 wt %.

Table 1. Specific Surface Area and Porous Parameters of Porous Carbons.

| sample (WCS biochar/ZnO/KOH) | SBETa/m2 g–1 | Smesob/m2 g–1 | Smicroc/m2 g–1 | pore volume/cm3 g–1 | carbon yieldd (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO (1/2/0.8) | 1537 | 791 | 745 | 0.89 | 48 |

| CaCO3 (1/2/0.8) | 1305 | 529 | 776 | 0.77 | 48 |

| For Supercapacitor Application | |||||

| ZnO (1/2/1) | 1438 | 769 | 708 | 0.96 | 46 |

| CaCO3 (2/1/1.2) | 1435 | 701 | 733 | 0.84 | 44 |

BET surface area.

Mesopore surface area.

Micropore surface area.

Carbon yield/% = weight of carbon/weight of WCS biochar.

2.2. Effect of the ZnO/WCS Biochar Ratio on the Meso-/Micropore Surface Area

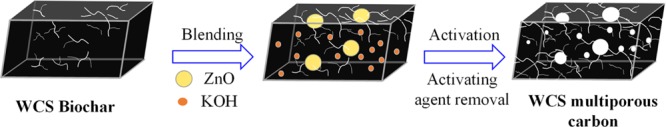

Interestingly, the content of the meso-/micropore surface area can be easily controlled by adding different amounts of ZnO nanoparticles at a fixed KOH/WCS biochar weight ratio. As the weight ratio of ZnO/WCS biochar increases from 0.5 to 2.5, both specific surface area and mesopore surface area increase significantly (Figure 2). This phenomenon can be ascribed to the reaction between ZnO and carbon at 900 °C (eqs 1–3).20 The additional reduction process allows the introduction of mesopores via pore widening. However, when the ratio of the ZnO/WCS biochar reaches 3.0, excessive corrosion of the carbon structure leads to lower specific surface area and carbon yield. A scheme of the mesopore formation mechanism is shown in Figure 3. Briefly, using easily removable ZnO nanoparticle and KOH as activating agents, multiporous carbons with a highly connective porous structure can be produced.

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

Figure 2.

Textural parameters of the WCS multiporous carbons (WCS biochar/KOH/ZnO = 1.0/0.5/0.5–3.0 in weight ratio).

Figure 3.

Scheme of the formation mechanism of the mesopore and micropore in the WCS biochar by using ZnO nanoparticles and KOH as activating agents.

Figure 4a shows the Raman spectrum of the WCS biochar and WCS multiporous carbons. Two broad peaks at 1350 cm–1 (D-band) and 1580 cm–1 (G-band) can be observed. To analyze the defect level of the carbons, the integrated intensity ratio of the D band to the G band was calculated. The high ID/IG values (0.71 and 0.75) reveal similar defect level in these carbon materials. The surface composition of the WCS biochar and WCS multiporous carbons was investigated by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), as shown in Figure 4b,c. The high-resolution C 1s spectra were deconvoluted into three main peaks. The peak at 284.8 eV can be attributed to the sp2-hybridized carbon (sp2 C–C). Meanwhile, the peaks at 285.8 and 288.4 eV demonstrate the presence of C–O and C=O bonds, respectively. From the XPS results, both WCS biochar and WCS multiporous carbon show high carbon content (77.3 and 85.9%). This indicates that after further pyrolysis of the WCS biochar, the unstable oxygen functional groups and defects in the WCS biochar were eliminated, which is consistent with the Raman results.

Figure 4.

(a) Raman spectra and XPS spectra of the (b) WCS biochar and (c) WCS multiporous carbons.

2.3. WCS Multiporous Carbons as the Electrode Material for Supercapacitor Applications

Although various activating agents or nanotemplating methods have been used to prepare porous carbons with high surface area (>2000 m2 g–1), the low tap density (0.3–0.4 g cm–3) and carbon yield17 make it difficult to employ them as electrode materials for supercapacitor applications. In contrast, for WCS multiporous carbons, the tap density can be well controlled at around 0.6–0.7 g cm–3, which is suitable for the preparation of supercapacitor devices. Herein, WCS multiporous carbons were used as electrode materials and 1.0 M LiClO4/PC was used as an electrolyte to assemble supercapacitors.

As can be seen from Figure 5a, the cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves of these electrodes show a quasi-rectangular shape at a fast scan rate, suggesting the ideal capacitor behavior and reversible redox reaction. The specific capacitance of the WCS multiporous carbons was calculated by integrating the CV curve area in a 0–1.5 V voltage window with a scan rate varying from 5.0 to 500.0 mV s–1. Owing to the high specific surface area, the WCS multiporous carbon supercapacitor has capacitance up to 128 F g–1 at a slow scan rate (5.0 mV s–1). The gravimetric capacitance of the samples at different scan rates is shown in Figure 5b. As the scan rate increases from 5 to 500 mV s–1, the decrease in capacitance is less than 40%. Furthermore, Figure 5c shows the cycling performance of the WCS multiporous carbons. At a scan rate of 100 mV s–1, the above-mentioned electrodes show a high initial specific capacity of 98 F g–1 and retain 98 F g–1 (>99%) after 10,000 cycles. Thus, these specific capacities and retention rates of the WCS multiporous carbon are comparable to those of many reported literature studies in the organic electrolyte systems.21−25 This demonstrates that the WCS multiporous carbon electrodes exhibit high capacity values, high rate performances, and good capacitance retention, which can be ascribed to the high pore accessibility in the meso-/microporous structure.26−28

Figure 5.

(a) CV curves at scan rates of 5 and 500 mV s–1, (b) specific capacitance at different scan rates, and (c) cycling performance at a scan rate of 100 mV s–1 for the WCS multiporous carbon electrodes.

The galvanostatic charge/discharge (GCD) curves of the WCS multiporous carbon electrode under different current densities all reveal nearly symmetrical triangular shapes (Figure 6a). Furthermore, as can be seen from the Nyquist plot (Figure 6b), in a high-frequency region, the semicircle of the WCS multiporous carbon electrode has a small diameter, which confirms the low ionic diffusion resistance within the multiporous carbon matrix. To evaluate the energy storage performance of the WCS multiporous carbon supercapacitor, Ragone plots (energy density vs powder density) are shown in Figure 6c. The gravimetric values exhibit a high power density of 6564 W kg–1 at 4.35 W h kg–1 energy density. To further explore the feasibility of the WCS multiporous carbon, a 1500 F-class pouch cell-typed supercapacitor has been prepared to evaluate its electrochemical performance (Figure S4).

Figure 6.

(a) GCD curves under different current densities, (b) Nyquist plots, and (c) Ragone plot for the WCS multiporous carbon electrodes in a 1.0 M LiClO4/PC electrolyte.

2.4. WCS Multiporous Carbons Prepared by CaCO3 Nanoparticles

Apart from ZnO nanoparticles, WCS multiporous carbons can also be prepared with CaCO3 nanoparticles and KOH via the same activation procedure. The dimension of CaCO3 nanoparticles is around 50 nm, as shown in Figure S3. As shown in Figure 7a, the CaCO3 nanoparticles are also capable of increasing both the pore volume and surface area. At WCS biochar/CaCO3/KOH weight ratio = 1.0:2.0:0.8, the porous carbon exhibits a specific surface area up to 1305 m2 g–1 (Figure 7b and Table 1). For the CaCO3 activating agent, the decomposition of CaCO3 to CaO (eq 4) produces CO2 for physical activation (eqs 4 and 5).

| 4 |

| 5 |

Figure 7.

(a) SEM images and (b) N2 sorption isotherms for the WCS multiporous carbon prepared by the CaCO3 nanoparticle and its (c) CV curves and (d) Nyquist plots in a 1.0 M LiClO4/PC electrolyte.

The CV (Figure 7c) of the as-prepared WCS multiporous carbon also shows quasi-rectangular curves with symmetric shape. The capacitance values were 102 and 73 F g–1 at 5 and 500 mV s–1 scan rates, respectively, with a retention rate up to 70%. The Nyquist plots present similar impedance behavior to that of the ZnO activating agent, in which the resistance is only 1.0 Ω (Figure 7d).

3. Conclusions

In this research, we proposed a facile solvent-free physical blending method to synthesize the WCS multiporous carbons with high surface area (>1200 m2 g–1) from the WCS biochar precursor by using ZnO and CaCO3 nanoparticles for the formation of mesopores and KOH to produce micropores. Conclusively, the physical blending method provides a facile way to fabricate the multiporous carbons from different carbon precursors. The porous structure can be easily tuned by adjusting the template to biochar weight ratio. With large surface area, high porous connectivity, and appropriate bulk density, the multiporous carbons can be assembled to high-performance supercapacitors with high power density and good retention rate at high scanning rate (>60%). In future, introduction of high content of nitrogen into the carbon matrix of the biochars or multiporous carbons will be studied for catalytic and electrochemical applications.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Synthesis of the WCS Multiporous Carbons via a Physical Blending Method

To synthesize the WCS multiporous carbons, x g (x = 10.0–50.0 g) of inorganic ZnO or CaCO3 nanoparticles, 10.0 g of carbon precursor (WCS biochar, from Guantian District, Tainan), and y g (y = 8.0–20.0 g) of the KOH activating agent were directly blended into a homogeneous mixture by using a blender. The resulted powder was then sealed in a stainless-steel container and heated in a furnace. The heating rate was set at 8 °C min–1 and held at 900 °C for 2 h. After cooling to room temperature, the sample was washed with water to remove the alkaline oxides and then soaked in 37% HCl solution to remove the residual inorganic activation agents. The following solution was then filtrated, washed, and dried at 100 °C in an oven for 5 h, yielding the WCS multiporous carbons. A scheme of the synthetic process is presented in Figure S5 (see the Supporting Information).

4.2. Structural Characterization

The thermal stability of the sample was characterized using a TGA (TA Instruments Q50, USA), heated from 100 to 800 °C with a ramp rate of 20 °C min–1 under air. SEM images of the WCS biochar and WCS multiporous carbon were recorded using a field emission scanning electron microscope (JEOL JSM7000F, USA). The N2 sorption isotherms of the samples were taken at 77 K on a Micrometric TriStar II apparatus to estimate the pore size, pore volume, and surface area. A micro-Raman spectrometer from Renishaw with a He–Ne laser source with a wavelength of 633 nm was used to determine the structure of the carbon samples. The XPS spectra of the samples were recorded using a PHI 5000 VersaProbe ESCA spectrometer with Al Kα as the excitation source. The XPS analysis results were calibrated against the C 1s peak at 284.8 eV as an internal standard.

4.3. Electrochemical Measurement

A symmetrical two-electrode capacitor cell was used to examine the electrochemical performance of the carbon electrodes. Both electrodes were made by depositing 2.0 mg carbons on a 1.0 cm2 stainless foil, which acted as a current collector. The cell consisted of two carbon electrodes, sandwiching a cellulose filter paper as the separator. CV measurements were conducted between 0 and 1.5 V in a 1.0 M LiClO4/PC electrolyte at sweep rates ranging from 5 to 500 mV s–1. Plots of the specific capacitance versus the voltage were calculated using the following formula: C = 2I/vm, where I = current (A), v = scan rate (V s–1), and m denotes the mass (g) of the carbon material in one electrode. GCD tests were performed in 1.5 V at current densities up to 18.0 A g–1 in a 1.0 M LiClO4/PC electrolyte. The specific gravimetric capacitance of a single electrode (F g–1) determined from the galvanostatic cycles was calculated by means of the formula: C = 2I/(dV/dt)m, where dV/dt = slope of the discharge curve (V s–1). Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy measurements were conducted at an open-circuit voltage (0 V) over the frequency range of 1 mHz to 100 kHz with a 5.0 mV amplitude.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taipei, Taiwan, for their generous financial support of this research (MOST 108-2622-E-006-017-CC1 and MOST 108-2113-M-006-011).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c01212.

Carbonization furnace systems, SEM image for ZnO and CaCO3 nanoparticles, TGA curve for WCS multiporous carbons, WCS multiporous carbon pouch cell-typed supercapacitor, and synthesis procedure (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Wang L.; Ding W.; Sun Y. The Preparation and Application of Mesoporous Materials for Energy Storage. Mater. Res. Bull. 2016, 83, 230–249. 10.1016/j.materresbull.2016.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Zhang L.; Cui K.; Ge S.; Cheng X.; Yan M.; Yu J.; Liu H. Flexible Electronics Based on Micro/Nanostructured Paper. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1801588. 10.1002/adma.201801588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzaffar A.; Ahamed M. B.; Deshmukh K.; Thirumalai J. A Review on Recent Advances in Hybrid Supercapacitors: Design, Fabrication and Applications. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2019, 101, 123–145. 10.1016/j.rser.2018.10.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He Y.; Zhuang X.; Lei C.; Lei L.; Hou Y.; Mai Y.; Feng X. Porous Carbon Nanosheets: Synthetic Strategies and Electrochemical Energy Related Applications. Nano Today 2019, 24, 103–119. 10.1016/j.nantod.2018.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y.; Gu L.; Guo S. W.; Shao S.; Li Z. L.; Sun Y. H.; Hao S. J. N-Doped Mesoporous Carbons: From Synthesis to Applications as Metal-Free Reduction Catalysts and Energy Storage Materials. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 761. 10.3389/fchem.2019.00761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.-Q.; Lu M.; Tao P.-Y.; Zhang Y.-J.; Gong X.-T.; Yang Z.; Zhang G.-Q.; Li H.-L. Hierarchically Porous and Heteroatom Doped Carbon Derived from Tobacco Rods for Supercapacitors. J. Power Sources 2016, 307, 391–400. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2016.01.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benzigar M. R.; Talapaneni S. N.; Joseph S.; Ramadass K.; Singh G.; Scaranto J.; Ravon U.; Al-Bahily K.; Vinu A. Recent Advances in Functionalized Micro and Mesoporous Carbon Materials: Synthesis and Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 2680–2721. 10.1039/c7cs00787f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.-G.; Liu H.; Sun H.; Hua W.; Wang H.; Liu X.; Wei B. One-Pot Synthesis of Nitrogen-Doped Ordered Mesoporous Carbon Spheres for High-Rate and Long-Cycle Life Supercapacitors. Carbon 2018, 127, 85–92. 10.1016/j.carbon.2017.10.084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnadurai D.; Karuppiah P.; Chen S.-M.; Kim H.-j.; Prabakar K. Metal-Free Multiporous Carbon for Electrochemical Energy Storage and Electrocatalysis Applications. New J. Chem. 2019, 43, 11653–11659. 10.1039/c9nj01875a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrero G. A.; Sevilla M.; Fuertes A. B. Mesoporous Carbons Synthesized by Direct Carbonization of Citrate Salts for Use as High-Performance Capacitors. Carbon 2015, 88, 239–251. 10.1016/j.carbon.2015.03.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y.; Xie Y.; Zou K.; Ji X. Review on Recent Advances in Nitrogen-Doped Carbons: Preparations and Applications in Supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 1144–1173. 10.1039/c5ta08620e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Samiee L.; Tasharrofi S.; Hassani S. S.; Fardi M.; Mazinani B. Novel and Economic Approach for Synthesis of Mesoporous Silica Template and Ordered Carbon Mesoporous By Using Cation Exchange Resin. Curr. Nanosci. 2017, 13, 595–603. 10.2174/1573413713666170616093238. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou T.; Jiang Q.; Wang L.; Qiu Z.; Liu Y.; Zhou J.; Liu B. Facile Preparation of Nitrogen-Enriched Hierarchical Porous Carbon Nanofibers by Mg(OAc)2-Assisted Electrospinning for Flexible Supercapacitors. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 456, 827–834. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.06.214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes T. C.; Xiao C.; Zhou F.; Li H.; Knowles G. P.; Hilder M.; Somers A.; Howlett P. C.; MacFarlane D. R. In-Situ-Activated N-Doped Mesoporous Carbon from a Protic Salt and Its Performance in Supercapacitors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 35243–35252. 10.1021/acsami.6b11716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Zhang C.; Shen Y.; Zhou Z.; Yu J.; Li Y.; Wei W.; Liu S.; Zhang Y. Environment-Friendly Preparation of Porous Graphite-Phase Polymeric Carbon Nitride using Calcium Carbonate as Templates, and Enhanced Photoelectrochemical Activity. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 5126–5131. 10.1039/c4ta06778a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J.; Zhang Z.; Xing W.; Yu J.; Han G.; Si W.; Zhuo S. Nitrogen-Doped Hierarchical Porous Carbon Materials Prepared from Meta-Aminophenol Formaldehyde Resin for Supercapacitor with High Rate Performance. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 153, 68–75. 10.1016/j.electacta.2014.11.075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G.-W.; Chen T.-Y.; Chung C.-H.; Lin H.-P.; Hsu C.-H. Hierarchical Micro/Mesoporous Carbons Synthesized with a ZnO Template and Petroleum Pitch via a Solvent-Free Process for a High-Performance Supercapacitor. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 2106–2113. 10.1021/acsomega.7b00308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese M.; Jiang J.; Lian K.; Holm N. High Capacitive Performance of Exfoliated Biochar Nanosheets from Biomass Waste Corn Cob. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 2903–2913. 10.1039/c4ta06110a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. P.; Adi V. S. K.; Huang H.-L.; Lin H.-P.; Huang Z.-H. Adsorption of Metal Ions with Biochars Derived from Biomass Wastes in a Fixed Column: Adsorption Isotherm and Process Simulation. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2019, 76, 240–244. 10.1016/j.jiec.2019.03.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Yang X.; Zhang F.; Long G.; Zhang T.; Leng K.; Zhang Y.; Huang Y.; Ma Y.; Zhang M.; Chen Y. Controlling the Effective Surface Area and Pore Size Distribution of sp2 Carbon Materials and Their Impact on The Capacitance Performance of These Materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 5921–5929. 10.1021/ja402552h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salunkhe R. R.; Young C.; Tang J.; Takei T.; Ide Y.; Kobayashi N.; Yamauchi Y. A High-Performance Supercapacitor Cell Based on ZIF-8-derived Nanoporous Carbon using An Organic Electrolyte. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 4764–4767. 10.1039/c6cc00413j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoller M. D.; Park S.; Zhu Y.; An J.; Ruoff R. S. Graphene-Based Ultracapacitors. Nano Lett. 2008, 8, 3498–3502. 10.1021/nl802558y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.-Q.; Liu R.-L.; Zhao D.-Y.; Xia Y.-Y. Electrochemical Properties of An Ordered Mesoporous Carbon Prepared by Direct Tri-constituent Co-Assembly. Carbon 2007, 45, 2628–2635. 10.1016/j.carbon.2007.08.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.; Wen J.; Yan C.; Rice Y.; Sohn H.; Shen M.; Cai M.; Dunn B.; Lu Y. High-Performance Supercapacitors Based on Hierarchically Porous Graphite Particles. Adv. Energy Mater. 2011, 1, 551–556. 10.1002/aenm.201100114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rufford T. E.; Hulicova-Jurcakova D.; Fiset E.; Zhu Z.; Lu G. Q. Double-layer Capacitance of Waste Coffee Ground Activated Carbons in An Organic Electrolyte. Electrochem. Commun. 2009, 11, 974–977. 10.1016/j.elecom.2009.02.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J.; Yang S.; Yang C.; Jia Q.; Yang X.; Cao B. Corncob-Derived Hierarchical Porous Carbons Constructed by Re-activation for High-Rate Lithium-Ion Capacitors. New J. Chem. 2019, 43, 10103–10108. 10.1039/c9nj01340g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J.; Yang S.; Ai J.; Yang C.; Jia Q.; Cao B. Hierarchical Porous Activated Carbon Obtained by a Novel Heating-Rate-Induced Method for Lithium-Ion Capacitor. ChemistrySelect 2019, 4, 5300–5307. 10.1002/slct.201900366. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J.; Yang S.-H.; Li S.-S.; Cao B.-Q. Double-Activated Porous Carbons for High-Performance Supercapacitor Electrodes. Rare Met. 2017, 36, 449–456. 10.1007/s12598-017-0896-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.