Abstract

Objectives:

Although the prevalence and mental health consequences of childhood maltreatment among adolescents have been studied widely, there are few data addressing these issues in Asian lower middle–income countries. Here, we assessed the prevalence and types of childhood maltreatment and, for the first time, examined their association with current mental health problems in Indian adolescents with a history of child work.

Methods:

One hundred and thirty-two adolescents (12–18 years; 114 males, 18 females) with a history of child work were interviewed using the Child Maltreatment, Conventional Crime, and Witnessing and Indirect Victimisation modules of the Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire. Potential psychiatric diagnoses and current emotional and behavioural problems were assessed using the culturally adapted Hindi versions of the Youth’s Inventory–4R and the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, respectively.

Results:

A large proportion of the sample reported childhood abuse or neglect (83.36%), direct or indirect victimisation (100%) and experienced symptoms of one or more psychiatric disorders (83.33%). Of the most common maltreatment types, physical abuse was present for 72.73% (extra-familial 56.25%, intra-familial 42.71%), emotional abuse for 47.7% (extra-familial 74.6%, intra-familial 12.9%), general neglect for 17.4% and unsafe home for 45.5% of the adolescents. All these maltreatment types were associated with poor mental health, with emotional abuse showing the strongest and wide-ranging impact.

Conclusions:

Indian adolescents with a history of child work are at an extremely high risk of extra-familial physical and emotional abuse as well as victimisation. They also experience a range of psychiatric symptoms, especially if they suffered emotional abuse. There is an urgent need for routine mental health screening and to consider emotional abuse in all current and future top-down and bottom-up approaches to address childhood maltreatment, as well as in potential interventions to ameliorate its adverse effects on mental health and well-being, of child and adolescent workers.

Keywords: Physical abuse, emotional abuse, neglect, psychiatric diagnoses, victimisation

Introduction

Child maltreatment, comprising physical, psychological, sexual abuse, as well as neglect, is recognised globally as a serious public concern, involving health, human rights, legal and social issues (Butchart et al., 2006). According to meta-analyses of global prevalence of child maltreatment, about 18% of the population report experiencing physical abuse, 36% emotional abuse, and 18% of the girls and 8% of the boys report sexual abuse (Stoltenborgh et al., 2011, 2012, 2013b). There is evidence of worldwide prevalence of childhood physical neglect in 16% and of emotional neglect in 18% of the population (Stoltenborgh et al., 2013a). These figures, however, come from research studies that focussed mainly on sexual abuse and were conducted mostly in the developed high-income countries (Stoltenborgh et al., 2015). The prevalence of child maltreatment, especially physical abuse, may be even higher in lower middle–income countries (LMICs), such as India, where corporal punishment and child work are more common and culturally accepted (Kacker et al., 2007).

According to a report by the Ministry of Women and Child Development in India (Kacker et al., 2007; N = 2211), around two thirds (69%) of children and young people in the general population experienced physical abuse in one or more situations by family members (48.47%) or others (34%). Sexual abuse in some form was reported by 42%, with 50% of the abusers being family or family friends. Emotional abuse was reported for about 50%, with parents being the abusers in most cases (83%). There was non-significant or marginal gender difference in physical, sexual or emotional abuse, but the majority of girls (70.57%) reported girl child neglect (i.e. girls receiving less care and fewer resources than boys of the same family). A more recent study in India involving school-going adolescents (Daral et al., 2016) also showed physical abuse to be the most common form of childhood maltreatment (42.6%), followed by emotional neglect (40.1%) and emotional abuse (37.9%). Many types of abuse and neglect were reported for nearly all street children in North-Western India (Mathur et al., 2009), suggesting that children from socioeconomically disadvantaged sectors may be at an extremely high risk of maltreatment (Walsh et al., 2019).

Childhood maltreatment has a range of negative consequences that begin in childhood, often lasting through adulthood to old age (e.g. Cicchetti and Toth, 2005; Corso et al., 2008; Draper et al., 2008; Fergusson et al., 2008; Gould et al., 2012; Shin et al., 2013). These include mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, substance abuse, eating disorders, suicidal symptomatology, psychosis and personality disorder (Bendall et al., 2008; Muniz et al., 2019; Norman et al., 2012; Teicher and Samson, 2013) and a worse-than-usual response to standard treatment approaches to ameliorate them (Nanni et al., 2012; Teicher and Samson, 2013).

There are no studies, to our knowledge, that focussed specifically on mental health of child workers in India, a huge population of 11.72 million as per the last Census (2011), who might be at a particularly high risk of maltreatment and victimisation due to both the factors that lead them to engage in child work, and the factors associated with it (Government of India, 2011). Poverty is considered the main reason for child labour in India (with parents sending their children to work to increase family income, or to work for money lenders in lieu of unpaid debt, rather than to school which they may also not be able to afford), with further possible reasons being addiction, disease/disability and socioeconomic backwardness of the parents, and recently the need for cheap labour in the context of globalisation and privatisation (Lal, 2019). Typically, child workers in India are employed illegally (Caesar-Leo, 1999) and, like street children, vulnerable to maltreatment both outside and within family environments, including abuse, neglect and missed out opportunities for normal development.

The aims of the this study were to identify the prevalence of various types of childhood maltreatment, and their associations with mental health problems, in adolescents with a history of child work in India. We hypothesised that there will be a high prevalence (>70%) of childhood maltreatment in these adolescents, especially of extra-familial type given the likelihood of them spending much time away from their families and engaging in unprotected work. We further hypothesised that adolescents with a history of significant childhood maltreatment will have worse mental health outcomes than those without, in line with the findings of our recent study of child and adolescent workers in Nepal (Dhakal et al., 2019).

Methods

Participants

The study involved 132 adolescents (114 males, 18 females; mean age: 14.70 years, SD = 1.67, range 12–18 years) who had worked as domestic helpers or in public or private organisations (e.g. shops, garages, hotels, carpentries, brick kilns, rag picking, agricultural farms). Of these, 100 adolescents were recruited from five child care homes (3 Delhi, 1 Varanasi, 1 Jaipur) of which two were for females only (Delhi) and the remaining three were for males only. These care homes provide shelter and care to rescued child workers or children in need of care and protection and have provisions for medical and educational facilities up to the higher secondary school. Care homes did not provide routine mental health check-ups but provided access to psychological counselling, mostly by social workers. We first sought permission from the care home manager or other senior staff in managerial capacity to approach and interview these adolescents, and then approached the care home staff with a request to identify suitable participants and, for those willing to participate (>95% response rate), to provide written consent as their primary caregivers. The remaining 32 adolescents with prior work history (but currently living on their own/with family) were recruited from within and around Varanasi. The inclusion criteria required all participants to be fluent in Hindi and have a history of child labour but no physical disability.

The study was approved by the Institute of Medical Science Research Ethics Committee of Banaras Hindu University (Ref. No. 265). All potential participants were given detailed information about the study, and all included participants provided written, as well as audiotaped, informed consent. For some non-care home participants (<16 years) who did not have a primary caregiver, consent was witnessed by someone unrelated to the study.

Measures

Demographics and work history

Demographic information about the care home participants and their work history, along with care home characteristics (e.g. occupancy and services provided), were obtained from the care home staff. Demographic information and prior work history of community participants was obtained directly from them.

Lifetime history of abuse, neglect, and victimisation

We used the Hindi version (see Supplemental Appendix 1) of the Conventional Crime, Child Maltreatment, and Witnessing and Indirect Victimisation modules of the Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire (JVQ; Finkelhor et al., 2005). As our focus was on childhood maltreatment, the full Child Maltreatment module (covering physical abuse, psychological/emotional abuse, general neglect and custodial interference) was administered, and responses to five additional supplementary neglect items (parental substance abuse, left alone/unsupervised, afraid of invited guests, living in an unsafe home and physical neglect) were also obtained. Only abbreviated modules of Conventional Crime, and Witnessing and Indirect Victimisation were administered. In addition, two items of the Sexual Victimisation domain (sexual assault by known adult, non-specific sexual assault) were used to assess sexual victimisation as per the guidelines if the Sexual Victimisation module is not administered.

Emotional and behavioural problems

We used the Hindi version (for psychometric properties, see Supplemental Appendix 1) of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 1997). It contains 25 attributes and the respondents use a 3-point Likert-type scale (1 = not true to 3 = certainly true) to indicate how far each attribute applies to them. The SDQ has five scales, each with five items: (1) emotional symptoms, (2) conduct problems, (3) hyperactivity/inattention, (4) peer relationship problems and (5) prosocial behaviour. All these scales, except prosocial behaviour, are summed up to generate a total difficulty score. An impact supplement was used to enquire further about overall distress, social impairment, burden and chronicity. There are cut-off scores on each of these scales to generate normal, borderline and abnormal-level categories.

Potential psychiatric diagnoses

We used the Hindi version (Supplemental Appendix 1) of the Youth’s Inventory–4R (YI-4R; Gadow et al., 2002). It contains 120 items to screen for a range of disorders (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [ADHD], conduct, oppositional defiant, anxiety, phobias, panic attack, obsession–compulsion, disturbing events post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), tics, somatisation, schizoid personality, schizophrenia, major depression, dysthymia, bipolar, eating problems [anorexia and bulimia] and substance use) as per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.; DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria. The participants are asked to indicate their frequency of experiencing the given symptoms using a 4-point scale (0 = never to 3 = very often).

Procedure

Participants were assessed individually by the researchers face-to-face in a single session. All sessions were conducted in a quiet room/area ensuring participant’s privacy and confidentiality. The complete assessment (SDQ, followed by YI-4R and JVQ) took about 2–3 hours, including one or two breaks as required.

Data analysis

The frequencies of lifetime experiences of abuse, neglect and victimisation (JVQ) along with current emotional and behavioural problems (SDQ) and potential psychiatric diagnoses (YI-4R) were calculated and compared, using chi-square test, between (1) boys and girls, given known gender differences in prevalence of many psychiatric disorders (Altemus et al., 2014) and (2) younger (12–14 years) and older adolescents (15–18 years), since Indian children ⩽14 years of age appear particularly susceptible to physical abuse (Kacker et al., 2007). Possible differences in demographics, work history, abuse, neglect, victimisation, emotional and behavioural problems, and potential psychiatric diagnoses between care home and community participants were also explored, using t test or chi-square test (for categorical variables). We then examined possible differences, using chi-square test, between the proportion of participants in the abused and non-abused categories (different types of abuse/neglect as assessed by the JVQ) who reported psychiatric symptoms (YI-4R) and abnormal levels of emotional and behavioural problems (SDQ).

Since the psychiatric symptoms (YI-4R) as well as emotional and behavioural problem scores (SDQ) are continuous data (used to ascertain presence of certain diagnoses/problems), and dichotomising continuous data often leads to reduced power and higher chances of false positive results (Altman and Royston, 2006), we also conducted one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs), with abuse status (abused, non-abused) as a between-subjects factor on 10 symptom domains of the YI-4R (ADHD, conduct disorder, oppositional defiant, generalised anxiety, separation anxiety, schizophrenia, major depression, dysthymia, bipolar disorder and eating problem dimensions) and SDQ scores (emotional problems, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, peer relationship problems and prosocial behaviour) to achieve a robust evaluation of the impact of childhood maltreatment on mental health. The remaining YI-4R domains were not subjected to ANOVA because they consist of only one or two items and are considered unsuitable for assessing severity. Although homogeneity of variance assumption for conducting ANOVA was met, the assumption of normality (skewness/kurtosis values >±2) was found to be violated for seven (conduct disorder, schizophrenia, depression, dysthymia, eating problems, prosocial and impact score) of the 17 variables (10 YI-4R, 7 SDQ). We conducted a Welch’s F test for these, and a standard ANOVA for the remaining variables.

Data were analysed using SPSS 24.0 for Windows. The alpha level for significance (2-tailed) was set at p ⩽ 0.05.

Results

Sample characteristics

Demographics

Of 132 participants, 67 were aged 12–14 years and 65 were aged 15–18 years. On average, participants recruited from care homes (N = 100) were younger (mean = 14.38 years, SD = 1.64) than those from the community, mean: 15.78 years, SD = 1.45; t(130) = 4.31, p < 0.001.

Prior work history

The age at which the participants started working ranged from 4 to 17 years (mean: 11.33; SD = 3.11), with a quarter (26.6%) working before the age of 10. Compared to non-care home participants, care home participants had started to work at a younger age (care home: mean age: 10.60, SD = 3.05; non-care home: 13.53, SD = 2.14), t(130) = 5.04, p < 0.001. Of the total sample, 37.87% of the adolescents reported living with their employer and 37.12% reported living with parents while they worked. The remaining lived alone or with friends or family. Sixty-five percent of the sample worked for ⩾10 hours a day, and just over half (55%) of them reported working 7 days a week. More than one third (38.64%) claimed to be working because of poverty while others listed such reasons for working as runaway (10.6%), enjoyment and better life (7.57%), or multiple reasons (14.39%).

Childhood maltreatment, victimisation and mental health in adolescents with a history of child work (entire sample)

Childhood maltreatment

Of the total sample, 83.36% reported one or more types of abuse or neglect (Table 1). Lifetime experience of physical abuse was reported by 72.73% of the sample (N = 96), with a mean frequency of 47.15 (SD = 43.34). Among physically abused adolescents, intra-familial physical abuse was reported by 42.71% and extra-familial physical abuse by 56.25%. On average, the most severe incident of physical abuse occurred at 10.55 years (SD = 3.0) while the first incident of physical abuse occurred at 7.95 years (SD = 3.03). Most participants (71.9%) reported abuse by a weapon/tool (e.g. rod or brick), and many (41.7%) suffered major injuries as a result (e.g. bloody nose). Nearly two thirds reported feeling very afraid (66.3%) while thinking about their most severe incident of physical abuse.

Table 1.

Frequency count and percentage of various maltreatment types and victimisation (JVQ) in relation to gender and age.

| Maltreatment types and victimisation | Total sample (N = 132) |

Gender |

Age group |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n = 114) |

Female (n = 18) |

χ2(df = 1) | p | 12–14 years (n = 67) |

15–18 years (n = 65) |

χ2(df = 1) | p | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||||

| Childhood maltreatment (any) | 114 (86.36) | 96 (84.2) | 18 (100) | 3.27 | 0.07 | 64 (95.52) ↑ | 50 (76.92) | 9.62 | 0.002 |

| Physical abuse | 96 (72.7) | 81 (71.1) | 15 (83.3) | 1.16 | 0.28 | 57 (85.1) ↑ | 39 (60.0) | 10.40 | 0.001 |

| Emotional abuse | 63 (47.7) | 51 (44.7) | 12 (66.7) | 2.99 | 0.08 | 36 (53.7) | 27 (41.5) | 1.95 | 0.16 |

| General neglect | 23 (17.4) | 17 (14.9) | 6 (33.3) | 3.63 | 0.06 | 14 (20.9) | 9 (13.8) | 1.15 | 0.28 |

| Custodial interference/family abduction | 4 (3.0) | 2 (1.8) | 2 (11.1) ↑ | 4.49 | 0.03 a | 3 (4.5) | 1 (1.5) | 1.00 | 0.32 |

| Supplemental neglect 1 (parental substance abuse) | 17 (12.9) | 12 (10.5) | 5 (27.8) ↑ | 4.12 | 0.04 a | 10 (14.9) | 7 (10.8) | 0.49 | 0.48 |

| Supplemental neglect 2 (left alone/unsupervised) | 7 (5.3) | 7 (6.1) | 0 (0) | 1.15 | 0.28 | 3 (4.5) | 4 (6.2) | 0.19 | 0.66 |

| Supplemental neglect 3 (afraid of invited guests) | 9 (6.8) | 7 (6.1) | 2 (11.1) | 0.6 | 0.43 | 4 (6) | 5 (7.7) | 0.15 | 0.70 |

| Supplemental neglect 4 (living in unsafe home) | 60 (45.5) | 52 (45.6) | 8 (44.4) | 0.01 | 1.00 | 38 (56.7) ↑ | 22 (33.8) | 6.93 | 0.008 |

| Supplemental neglect 5 (physical neglect) | 8 (6.1) | 3 (2.6) | 5 (27.8) ↑ | 17.27 | <0.001 a | 5 (7.5) | 3 (4.6) | 0.48 | 0.49 |

| Sexual abuse (by known person) | 6 (4.5) | 4 (3.5) | 2 (11.1) | 2.06 | 0.15 | 2 (3.0) | 4 (6.2) | 0.77 | 0.38 |

| Sexual abuse (by unknown person) | 3 (2.3) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (11.1) ↑ | 7.17 | 0.007 a | 1 (1.5) | 2 (3.1) | 0.38 | 0.54 |

| Witnessing indirect victimisation | 132 (100) | 114 (100) | 18 (100) | = | = | 67 (100) | 65 (100) | = | |

| Conventional crime | 132 (100) | 114 (100) | 18 (100) | = | = | 67 (100) | 65 (100) | = | |

‘↑’ indicates higher scores; ‘=’ denotes 100% in both groups.

Effect based on small n.

Lifetime experience of emotional abuse was reported by 47.7% of the sample, with a mean frequency of 57.41 (SD = 44.38). The mean age at which the most severe incident of abuse occurred was 11.13 years (SD = 3.09) while the mean age at which the first recalled incident of emotional abuse occurred was 8.76 years (SD = 3.11). Among emotionally abused adolescents, 12.7% reported intra-familial emotional abuse while 74.6% reported extra-familial emotional abuse. About one fourth (25.4%) reported being very afraid when thinking about the emotional abuse incident/s. In addition, general neglect was reported by 17.2%, unsafe home by 45.5%, parental substance abuse by 12.9% and sexual abuse by known or unknown person by 6.8% of the sample. Compared to boys, a greater proportion of girls reported incidents of physical neglect, custodial interference, sexual abuse by unknown person and parental substance abuse (Table 1). A significantly higher proportion of younger adolescents (12–14 years), compared to older adolescents (15–18 years), reported incidents of physical abuse and unsafe home (Table 1). Participants from care homes reported higher rates of physical abuse, emotional abuse, parental substance abuse and unsafe home compared to those from community settings (Supplemental Appendix 2).

Victimisation history

All the participants (100%) reported experiencing at least one form of victimisation and had been exposed to some type of conventional crime in their lifetime (Table 1). Of the total sample, 28.8% had experienced three different forms of indirect victimisations and 95.5% had been exposed to more than one type of conventional crime. Indirect victimisation was mostly reported in terms of witnessing assault without weapon (85.5%), followed by witnessing assault with weapon (78.6%), witnessing parent assault of sibling (64.1%) and witnessing domestic violence (52.3%). Similarly, for exposure to direct victimisation, majority reported being assaulted without weapon (83.3%), followed by incidents of being assaulted with weapon (74.2%), theft (65.2%) and attempted assault (59.8%). There were no marked differences between victimisation experiences of care home and community participants (Supplemental Appendix 2).

Potential psychiatric diagnoses

Of 132 adolescents, 110 adolescents (83.33%) had symptoms of one or more disorders (Table 2). The majority had symptoms of specific phobia (41.66%), conduct disorder (33.33%) and social phobia (30.33%). A higher proportion of boys reported symptoms of conduct disorder, while a higher proportion of girls reported symptoms of specific phobia, PTSD, somatisation, social phobia and dysthymia (Table 2). Age-related differences were also observed, with a higher proportion of younger adolescents reporting symptoms of specific phobia, motor tics, social phobia and separation anxiety compared to older adolescents (Table 2). More care home participants, compared to community participants, reported symptoms of generalised anxiety, specific phobia, panic attack, separation anxiety and dysthymia (Supplemental Appendix 3).

Table 2.

Number and percentage of participants meeting the symptom count criteria on YI-4R classified by age group and childhood maltreatment (any type of abuse or neglect).

| Total (N = 132) |

Age group |

Childhood maltreatment |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12–14 years n = 67 |

15–18 years n = 65 |

χ2(df = 1) | p | Present n = 114 |

Absent n = 18 |

χ2(df = 1) | p | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||||

| Overall (one or more disorders) | 111 (84.09) | 63 (94.03) ↑ | 48 (73.85) | 9.97 | 0.002 | 100 (87.72) ↑ | 11 (61.11) | 8.166 | 0.004 |

| ADHD | 3 (2.27) | 1 (1.5) | 2 (3.1) | 0.37 | 0.54 | 3 (2.63) | 0 (0) | 0.55 | 0.40 |

| Conduct | 44 (33.33) | 26 (38.8) | 18 (27.7) | 1.82 | 0.18 | 37 (32.46) | 7 (38.89) | 6.29 | 0.01 |

| Oppositional defiant | 15 (11.36) | 7 (10.4) | 8 (12.3) | 0.12 | 0.73 | 13 (11.40) | 2 (11.11) | 1.83 | 0.18 |

| Generalised anxiety | 15 (11.36) | 6 (9.0) | 9 (13.8) | 0.75 | 0.39 | 14 (12.28) | 1 (5.56) | 2.43 | 0.12 |

| Specific phobia | 55 (41.66) | 37 (55.2) ↑ | 18 (27.7) | 10.19 | 0.001 | 53 (46.49) ↑ | 2 (11.11) | 16.15 | <0.001 |

| Panic attack | 17 (12.87) | 12 (17.9) | 5 (7.7) | 3.04 | 0.08 | 17 (14.91) | 0 (0) | 3.56 | 0.06 |

| Obsession | 25 (18.93) | 11 (16.4) | 14 (21.5) | 0.56 | 0.46 | 24 (21.05) | 1 (5.56) | 4.94 | 0.03 |

| Compulsion | 22 (16.66) | 10 (14.9) | 12 (18.5) | 0.30 | 0.58 | 21 (18.42) | 1 (5.56) | 4.13 | 0.04 |

| Disturbing events (PTSD) | 11 (8.33) | 4 (6.0) | 7 (10.8) | 0.98 | 0.32 | 11 (9.65) | 0 (0) | 2.17 | 0.14 |

| Motor tics | 5 (3.78) | 5 (7.5) ↑ | 0 (0) | 5.03 | 0.02 | 5 (4.385) | 0 (0) | 0.93 | 0.33 |

| Vocal tics | 5 (3.78) | 3 (4.5) | 2 (3.1) | 0.18 | 0.68 | 4 (3.51) | 1 (5.56) | 0.40 | 0.53 |

| Somatisation | 10 (7.57) | 5 (7.5) | 5 (7.7) | 0.002 | 0.96 | 9 (7.89) | 1 (5.56) | 1.36 | 0.24 |

| Social phobia | 40 (30.30) | 26 (38.8) ↑ | 14 (21.5) | 4.64 | 0.03 | 36 (31.58) ↑ | 4 (22.22) | 7.30 | 0.01 |

| Separation anxiety | 11 (8.33) | 10 (14.9) ↑ | 1 (1.5) | 7.72 | 0.006 | 11 (9.65) | 0 (0) | 2.17 | 0.14 |

| Schizoid personality | 7 (5.30) | 2 (3.0) | 5 (7.7) | 1.44 | 0.23 | 6 (5.26) | 1 (5.56) | 0.77 | 0.38 |

| Schizophrenia | 4 (3.03) | 3 (4.5) | 1 (1.5) | 1.00 | 0.32 | 4 (3.51) | 0 (0) | 0.74 | 0.39 |

| Major depression | 7 (5.30) | 4 (6.0) | 3 (4.6) | 0.13 | 0.72 | 7 (6.14) | 0 (0) | 1.33 | 0.25 |

| Dysthymia | 24 (18.18) | 12 (17.9) | 12 (18.5) | 0.01 | 0.93 | 24 (21.05) ↑ | 0 (0) | 5.41 | 0.02 |

| Dysthymia – alternative version | 17 (12.87) | 8 (11.9) | 9 (13.8) | 0.11 | 0.74 | 17 (14.91) | 0 (0) | 3.56 | 0.06 |

| Bipolar disorder | 4 (3.03) | 3 (4.5) | 1 (1.5) | 1.00 | 0.32 | 4 (3.51) | 0 (0) | 0.74 | 0.39 |

| Anorexia | 2 (1.51) | 2 (3.0) | 0 (0) | 1.96 | 0.16 | 2 (1.75) | 0 (0) | 0.36 | 0.55 |

| Bulimia | 8 (6.06) | 4 (6.0) | 4 (6.2) | 0.002 | 0.96 | 7 (6.14) | 1 (5.55) | 0.96 | 0.33 |

| Substance use | 18 (13.63) | 9 (13.4) | 9 (13.8) | 0.004 | 0.95 | 14 (12.28) | 4 (22.22) | 1.40 | 0.24 |

‘↑’ indicates higher score. ADHD: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder.

Emotional and behavioural problems

On the SDQ, abnormal levels of emotional problems were reported by the majority (22%), followed by peer problems (20.5%), conduct problems (19.7%), total difficulty (18.9%), hyperactivity (13.6%) and abnormal (low) levels of prosocial behaviour (6.1%). These effects were unaffected by gender or age except borderline severity of conduct problems that was reported by a higher proportion of younger, compared to older, adolescents (younger [16.4%], older [4.6%]), χ2(1) = 4.815, p = 0.028. Care home and community participants did not differ significantly on any SDQ subscale except emotional problems with more care home participants reporting abnormal levels of emotional problems (care home [26%], non-care home [9.37%]), χ2(1) = 3.881, p = 0.049.

Abused versus non-abused groups

Rates of potential psychiatric diagnoses

A significantly higher proportion of physically abused participants met symptom count criteria (YI-4R) for specific phobia than those who had not been abused (physically abused, 46.9%, non-abused, 27.8%), χ2(1) = 3.90, p = 0.048. Same pattern was noted for dysthymia (physically abused, 22.9%; non-abused, 5.6%), χ2(1) = 5.23, p = 0.02. Similarly, a significantly higher proportion of emotionally abused participants, compared to non-abused participants, met symptom criteria for oppositional defiant disorder (abused, 17.5%, non-abused, 5.8%), χ2(1) = 4.44, p = 0.034; panic attack (abused, 19.0%, non-abused, 7.2%), χ2(1) = 4.07, p = 0.04; major depression (abused, 9.5%, non-abused, 1.4%), χ2(1) = 4.30, p = 0.038; and dysthymia (abused, 25.4%, non-abused, 11.6%), χ2(1) = 4.18, p = 0.04. General neglect and other dimensions did not significantly affect the rates of specific psychiatric disorders.

Severity of psychiatric symptoms

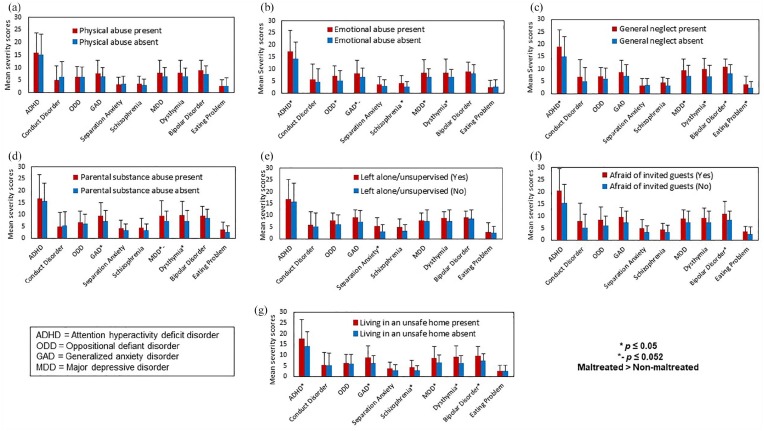

The ANOVAs on severity scores on the 10 YI-4R symptom domains (ADHD, conduct disorder, oppositional defiant, generalised anxiety, separation anxiety, schizophrenia, major depression, dysthymia, bipolar disorder and eating problem) revealed no significant effect of physical abuse, with the earlier reported effect in dysthymia now reduced to a trend at best, F(1, 130) = 2.416, p = 0.12 (Figure 1(a)).

Figure 1.

Symptom severity (Youth’s Inventory-4R) in adolescents with and without childhood maltreatment.

The effect of emotional abuse was significant for ADHD, F(1, 130) = 5.03, p = 0.027; oppositional defiant disorder, F(1, 130) = 6.68, p = 0.011; schizophrenia, F(1, 130) = 8.25, p = 0.005; major depression, F(1, 130) = 4.99, p = 0.027; and dysthymia, F(1, 130) = 4.12, p = 0.044; and it approached significance for generalised anxiety, F(1, 130) = 3.89, p = 0.051 (Figure 1(b)). The effect of general neglect was significant for ADHD, F(1, 130) =5.01, p = 0.027; major depression, F(1, 130) = 5.06, p = 0.026; dysthymia, F(1, 130) = 8.11, p = 0.005; bipolar disorder, F(1, 130) = 10.68, p = 0.001; and eating problems, F(1, 130) = 5.51, p = 0.020 (Figure 1(c)). The effect of parental substance abuse was significant for generalised anxiety disorder, F(1, 130) = 3.79, p = 0.05, and dysthymia, F(1, 130) = 4.26, p = 0.041; and it exhibited a trend for major depression, F(1, 130) = 3.86, p = 0.052 (Figure 1(d)). Similarly, the effect of ‘being left alone/unsupervised’ was seen for separation anxiety, F(1, 130) = 3.94, p = 0.049 (Figure 1(e)), while the effect of ‘being afraid of invited guests’ was seen for symptoms of bipolar disorder, F(1, 130) = 4.09, p = 0.045 (Figure 1(f)). When participants were compared on living in an unsafe home, those experiencing such a neglect were found to report higher symptoms of ADHD, F(1, 130) = 6.66, p = 0.011; generalised anxiety, F(1, 130) = 10.42, p = 0.002; schizophrenia, F(1, 130) = 8.08, p = 0.005; major depression, F(1, 130) = 6.91, p = 0.010; dysthymia, F(1, 130) = 11.49, p = 0.001; and bipolar disorder, F(1, 130) = 12.08, p = 0.001, compared to those who did not (Figure 1(g)). In all cases, abuse was associated with greater symptom severity (Figure 1(a)–(f)). Age at starting work, which happened to correlate with age in this sample, r(132) = 0.438, p < 0.001, had small negative correlations with severity of ADHD (r = –0.178, p = 0.04) and bipolar disorder (r = –0.276, p = 0.002) but not with any other symptoms.

Rates of abnormal level of emotional and behavioural problems

On the SDQ, a higher proportion of physically abused, compared to non-abused, adolescents reported abnormal level impact of emotional problems (abused, 15.6%, non-abused, 2.8%), χ2(1) = 4.00, p = 0.045. A higher proportion of emotionally abused, compared to non-abused, participants, reported abnormal levels of conduct problems (abused, 27.0%, non-abused, 13%), χ2(1) = 4.05, p = 0.044, and abnormal levels of overall difficulty (abused, 28.6%, non-abused, 10.1%), χ2(1) = 7.29, p = 0.007.

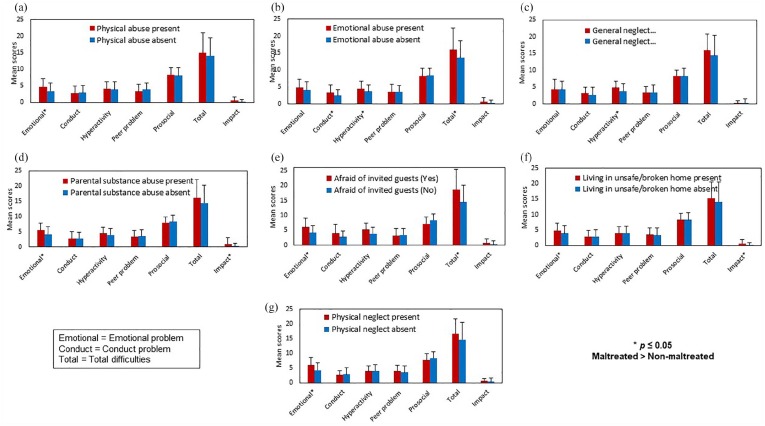

Severity of emotional and behavioural problems

The ANOVAs on the SDQ scales (continuous severity scores) revealed significant effect of physical abuse on emotional problems, F(1, 130) = 6.58, p = 0.011 (Figure 2(a)), and of emotional abuse on conduct problems, F(1, 130) = 5.82, p = 0.017; hyperactivity, F(1, 130) = 5.32, p = 0.023; and total SDQ difficulty score, F(1, 130) = 5.52, p = 0.02, with higher scores in abused, relative to non-abused, adolescents in all cases (Figure 2(b)). Participants with general neglect showed greater hyperactivity, F(1, 130) = 4.40, p = 0.038, than those without (Figure 2(c)). Adolescents who were exposed to parental substance abuse showed higher emotional problems, F(1, 130) = 4.49, p = 0.036, and impact scores, F(1, 130) = 5.12, p = 0.025, compared to those without parental substance abuse (Figure 2(d)). Similarly, participants who had been afraid of invited guests had higher emotional problems, F(1, 130) = 4.95, p = 0.028, and total difficulty scores, F(1, 130) = 4.63, p = 0.033, than participants not reporting such neglect (Figure 2(e)). Those who reported living in an unsafe home had higher emotional problems, F(1, 130) = 4.65, p = 0.033, and impact scores, F(1, 130) = 5.95, p = 0.016, relative to those without this form of neglect (Figure 2(f)). Finally, participants who had experienced physical neglect reported significantly higher emotional problems than those who did not experience this neglect, F(1, 130) = 4.41, p = 0.038 (Figure 2(g)).

Figure 2.

Emotional and behavioural problems (strengths and difficulties questionnaire) in adolescents with and without childhood maltreatment.

Discussion

This study examined the prevalence and types of childhood maltreatment and their association with current mental health problems among 12- to 18-year-old Indian adolescents with a history of child work. It yielded three sets of observations that deserve comment.

Childhood maltreatment among adolescents with child work history

As expected, a large proportion of the sample reported some form of childhood abuse or neglect. Specifically, a high proportion (>72%) reported physical abuse, followed by emotional abuse (47.7%), unsafe home (45.5%), general neglect (17.4%) and parental substance abuse (12.9%). There were more incidents of extra-familial than intra-familial abuse, especially for emotional abuse. Younger adolescents (aged 12–14 years) appeared more susceptible to abuse. Direct or indirect victimisation was present for all, with most (>95%) adolescents having experienced more than one type of conventional crime.

Our findings demonstrate an alarmingly high prevalence of childhood maltreatment and victimisation in Indian adolescents with a history of child work. No children should have to suffer maltreatment, or be required to work while they should be at school (which in itself is considered a form of abuse and neglect, Caesar-Leo, 1999). This, however, is perhaps unachievable while a sizable proportion of the world population remains below the poverty line, and many countries, including India, lack an effective welfare system. Even in the United Kingdom which has one of the best welfare systems and laws against forced child labour, there is evidence of considerable childhood maltreatment and victimisation which, when assessed in a research context, appears 7–17 times higher than the official rates of substantiated child maltreatment (though still much lower than the rates observed in our Indian sample) (Radford et al., 2013). In the United States, 60–80% of the children are reported to have experienced poly-victimisation which in turn associates with trauma symptoms (Finkelhor et al., 2009; Turner et al., 2010). Childhood maltreatment is clearly an issue of global significance, especially for at-risk populations in resource-poor settings such as the current sample, that requires attention from both health professionals, and law making and enforcing bodies (Singhi et al., 2013).

An unexpected finding was that two thirds of our sample were afraid to recall incidents of severe physical abuse. This raises the possibility that, because of the active suppression of (and possible dissociation from) the fear-inducing memories of abusive incidents, physical abuse might have been under-reported by adolescents who were not currently being abused. It would be valuable to examine how the fear of recalling physical abuse incidents relates to fear biases, for example in facial affect processing, that have been reported for physically abused children (Pollak and Tolley-Schell, 2003), and whether this fear may confer a vulnerability to mental disorders (Suzuki et al., 2015). Finally, there was a gender difference in the prevalence of some maltreatment types. Of these, the strongest difference related to more girls than boys reporting physical neglect. This is perhaps not surprising given the ‘girl child neglect’ phenomenon in India (Kacker et al., 2007).

Potential psychiatric diagnoses among adolescents with child work history

Overall, a much larger proportion of the sample (83.33%) met symptom criteria for one or more psychiatric disorders, relative to the current global estimates (15%; Polanczyk et al., 2015). The most prevalent likely diagnoses were specific phobia (41.66%); conduct disorder (33.33%); social phobia (30.30%); dysthymia, obsession, compulsion (16–20%); oppositional defiant, generalised anxiety, panic attack, PTSD, separation anxiety, substance abuse (8–15%); and depression, somatisation, bulimia, schizoid personality (5–7%), followed by schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and tics (3–4%). All of these appear elevated at least to some degree, relative to the global estimates (Polanczyk et al., 2015), suggesting that child work, with many associated disadvantages including poverty, low socio-economic status, parental addiction, lack of education and opportunities for normal development, exacerbates mental health issues (Thabet et al., 2011).

Our findings showing that certain disorders (specific phobia, social phobia, separation anxiety and motor tics) were more common in the younger (12–14 years), relative to older, adolescents, suggesting that young(er) children at work may be particularly susceptible to maltreatment (discussed earlier) as well as poor mental health. Previous research on lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders has shown anxiety disorders to have, on average, a much earlier onset (11 years; 50% cases by age 14) than mood disorders (30 years) (Kessler et al., 2005). This is particularly true for phobias (Kessler et al., 2007). It is thus plausible that child work and maltreatment act, perhaps jointly, to increase susceptibility to anxiety disorders in those ⩽14 years. There was also a higher prevalence of mental health problems in care home participants relative to our community participants. This might be explained by their (relatively) younger age and higher rates of physical and emotional abuse (discussed further), as well as parental neglect and other circumstances (e.g. dysfunctional family), which were also the most likely reasons for their care home placement. Finally, despite limited power to probe gender differences, we observed that a higher proportion of girls reported symptoms of specific phobia, PTSD, somatisation, social phobia and dysthymia, while a higher proportion of boys reported symptoms of conduct disorder, in line with previous evidence on this topic (Altemus et al., 2014).

Association between childhood maltreatment and mental health in adolescents with child work history

Our findings contribute to the growing body of literature on association between various types of childhood maltreatment and poor mental health. Specifically, a history of physical abuse was associated significantly with phobia, dysthymia and emotional problems. Emotional abuse was associated with a higher prevalence, or severity, of panic attack, generalised anxiety, depression, dysthymia, ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder and schizophrenia (YI-4R), and with higher rates of emotional and behavioural problems (SDQ). Although general neglect and other maltreatment dimensions did not significantly differentiate the abused and non-abused groups in terms of the proportion of adolescents meeting symptom criteria for specific disorders, they too were associated with greater symptom severity on many dimensions, especially anxiety and depression, and emotional problems (Figures 1 and 2). These findings are generally consistent with previous findings on this topic in the developed countries (Bendall et al., 2008; Muniz et al., 2019; Norman et al., 2012; Sullivan et al., 2019; Teicher and Samson, 2013), and stress the need for suitable and scalable interventions to ameliorate current mental health problems of such adolescents and to protect them against future episodes (Gustavson et al., 2018).

Notably, emotional abuse, which is not sufficiently addressed by present Indian laws, had the most wide-ranging impact of all maltreatment types on mental health (Figures 1 and 2) and appears to be a transdiagnostic risk factor for several psychiatric disorders. Although ours is the first study to report this finding in the Indian context, it is consistent with previous data from developed countries (e.g. in a meta-analysis for association of physical abuse, emotional abuse and neglect with depressive disorders, the largest odds ratio observed for emotional abuse, Norman et al., 2012; emotional abuse associated more strongly than neglect with increased odds of lifetime diagnoses of several mental disorders in a nationally representative US sample, Taillieu et al., 2016; emotional abuse more strongly associated with self-injury than neglect, Liu et al., 2018). It also concurs with a study of women with psychiatric disorders in India where emotional, but not physical or sexual, abuse differentiated them from healthy women (Jangam et al., 2015). Emotional abuse may further impact emotional responding (Zhu et al., 2019) and the prevalence of some mental disorders, for example major depression, that usually emerge later in life (Kessler et al., 2005, 2007), if emotionally abused adolescents are examined longitudinally. In addition, general neglect and specific neglect items, especially parental substance abuse and unsafe home (perhaps reflecting unsuitable accommodation while living with the employer for some, and poverty for others), too were associated with multiple mental health issues (Figures 1 and 2). Taken together, our findings underscore the need for attention to mental health issues of child workers, and to consider emotional abuse and neglect in both top-down (e.g. government laws and policies) and bottom-up (e.g. grassroot campaigns to raise awareness among the masses) efforts to counteract childhood maltreatment, as well as in psychological interventions to reduce its adverse impact on mental health.

Methodological considerations

First, the rates of abuse and neglect we observed may not be representative of the target population since a large proportion of our sample consisted of rescued child workers. Second, our sample lacked power to reliably probe gender differences. Third, although we followed established procedures for developing Hindi versions of the selected measures (Supplemental Appendix 1), Cronbach’s alphas for three of the SDQ subscales (Conduct Problem, Hyperactivity, Peer Problem) were considerably low, as has also been reported for the SDQ in other languages (Dhakal et al., 2019). Fourth, our results, in showing an association between the severity of abuse and neglect and psychiatric symptoms ratings, indicated that mental health issues were exacerbated by maltreatment but, with the current design (without a group of non-child workers), we were unable to determine the unique contributions of child work and maltreatment to mental health problems.

Conclusion

This study showed that nearly all young Indian adolescents with a history of child work experience childhood maltreatment, especially extra-familial physical and emotional abuse and victimisation. They also display a range of psychiatric symptoms, especially if they suffered emotional abuse. The findings highlight the need for routine mental health screening of child workers and to consider emotional abuse in all preventive approaches to thwart childhood maltreatment, as well as in rehabilitative efforts to lessen its adverse impact on current and future mental health.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Supplementary_Materials for Childhood maltreatment and its mental health consequences among Indian adolescents with a history of child work by Rakesh Pandey, Shulka Gupta, Aakanksha Upadhyay, Rajendra Prasad Gupta, Meenakshi Shukla, Ramesh Chandra Mishra, Yogesh Kumar Arya, Tushar Singh, Shanta Niraula, Jennifer Yun Fai Lau and Veena Kumari in Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Dr Urmila Rani Srivastava and Dr Manjari Shukla for their expert input to the development of the Hindi Versions of the Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire (JVQ), Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) and the Youth’s Inventory–4R (YI-4R).

Footnotes

Author Contributions: R.P., S.N., J.Y.F.L. and V.K. contributed to conception and design of the study; R.P., M.S., T.S., Y.K.Y., R.C.M., J.Y.F.L. and V.K. contributed to development of study materials; S.G., A.U., R.P.G. and R.P. contributed to acquisition of study data; S.G., M.S., R.P. and V.K. contributed to analysis and interpretation of study data; R.P., M.S. and V.K. wrote first draft of the paper; J.Y.F.L. critiqued the output for important intellectual content.

Data Accessibility Statement: All data supporting this study are available from Brunel University London research repository at 10.17633/rd.brunel.11876982.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Department of Biotechnology, India (BT/IN/DBT-MRC/DFID/20/RP/2015-16) and the UK Medical Research Council (MR/N006194/1).

ORCID iDs: Rakesh Pandey  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8024-300X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8024-300X

Jennifer Yun Fai Lau  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8220-3618

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8220-3618

Veena Kumari  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9635-5505

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9635-5505

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Altemus M, Sarvaiya N, Epperson CN. (2014) Sex differences in anxiety and depression clinical perspectives. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 35: 320–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman DG, Royston P. (2006) The cost of dichotomising continuous variables. BMJ 332: 1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bendall S, Jackson HJ, Hulbert CA, et al. (2008) Childhood trauma and psychotic disorders: A systematic, critical review of the evidence. Schizophrenia Bulletin 34: 568–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butchart A, Harvey AP, Mian M, et al. (2006) Preventing Child Maltreatment: A Guide to Taking Action and Generating Evidence. Geneva: WHO Press. [Google Scholar]

- Caesar-Leo M. (1999) Child labour: The most visible type of child abuse and neglect in India. Child Abuse Review: Journal of the British Association for the Study and Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect; 8: 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. (2005) Child maltreatment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 1: 409–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corso PS, Edwards VJ, Fang X, et al. (2008) Health-related quality of life among adults who experienced maltreatment during childhood. American Journal of Public Health 98: 1094–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daral S, Khokhar A, Pradhan S. (2016) Prevalence and determinants of child maltreatment among school-going adolescent girls in a semi-urban area of Delhi, India. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics 62: 227–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhakal S, Niraula S, Sharma NP, et al. (2019) History of abuse and neglect and their associations with mental health in rescued child labourers in Nepal. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 53: 1199–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper B, Pfaff JJ, Pirkis J, et al. (2008) Long-term effects of childhood abuse on the quality of life and health of older people: Results from the depression and early prevention of suicide in general practice project. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 56: 262–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. (2008) Exposure to childhood sexual and physical abuse and adjustment in early adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect 32: 607–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Hamby SL, Ormrod R, et al. (2005) The Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire: Reliability, validity, and national norms. Child Abuse & Neglect 29: 383–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. (2009) Lifetime assessment of poly-victimization in a national sample of children and youth. Childhood Abuse & Neglect 33: 403–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, Sprafkin J, Carlson GA, et al. (2002) A DSM-IV-referenced, adolescent self-report rating scale. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 41: 671–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. (1997) The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 38: 581–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould F, Clarke J, Heim C, et al. (2012) The effects of child abuse and neglect on cognitive functioning in adulthood. Journal of Psychiatric Research 46: 500–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of India (2011) Census Report. New Delhi, India: Ministry of Home Affairs, Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, Government of India. [Google Scholar]

- Gustavson K, Knudsen AK, Nesvåg R, et al. (2018) Prevalence and stability of mental disorders among young adults: Findings from a longitudinal study. BMC Psychiatry 18: 65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jangam K, Muralidharan K, Tansa KA, et al. (2015) Incidence of childhood abuse among women with psychiatric disorders compared with healthy women: Data from a tertiary care centre in India. Childhood Abuse and Neglect 50: 67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kacker L, Mohsin N, Dixit A, et al. (2007) Study on Child Abuse: India 2007. New Delhi, India: Ministry of Women and Child Development, Government of India. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, et al. (2007) Age of onset of mental disorders: A review of recent literature. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 20: 359–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. (2005) Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62: 593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal BS. (2019) Child labour in India: Causes and consequences. International Journal of Science and Research 8: 2199–2206. [Google Scholar]

- Liu RT, Scopelliti KM, Pittman SK, et al. (2018) Childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry 5: 51–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur M, Rathore P, Mathur M. (2009) Incidence, type and intensity of abuse in street children in India. Child Abuse & Neglect 33: 907–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muniz CN, Fox B, Miley LN, et al. (2019) The effects of adverse childhood experiences on internalizing versus externalizing outcomes. Criminal Justice and Behavior 46: 568–589. [Google Scholar]

- Nanni V, Uher R, Danese A. (2012) Childhood maltreatment predicts unfavorable course of illness and treatment outcome in depression: A meta-analysis. The American Journal of Psychiatry 169: 141–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, et al. (2012) The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Medicine 9: e1001349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polanczyk GV, Salum GA, Sugaya LS, et al. (2015) Annual research review: A meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 56: 345–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak SD, Tolley-Schell SA. (2003) Selective attention to facial emotion in physically abused children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 112: 323–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radford L, Corral S, Bradley C, et al. (2013) The prevalence and impact of child maltreatment in the United Kingdom. Child Abuse and Neglect 37: 801–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin SH, Miller DP, Teicher MH. (2013) Exposure to childhood neglect and physical abuse and developmental trajectories of heavy episodic drinking from early adolescence into young adulthood. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 127: 31–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhi P, Saini AG, Malhi P. (2013) Child maltreatment in India. Paediatrics and International Child Health 334: 292–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenborgh M, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Alink LRA, et al. (2012) The universality of childhood emotional abuse: A meta-analysis of worldwide prevalence. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 21: 870–890. [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenborgh M, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Alink LRA, et al. (2015) The prevalence of child maltreatment across the globe: Review of a series of meta-analyses. Child Abuse Review 24: 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenborgh M, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van Ijzendoorn MH. (2013. a) The neglect of child neglect: A meta-analytic review of the prevalence of neglect. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 48: 345–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenborgh M, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van Ijzendoorn MH, et al. (2013. b) Cultural–geographical differences in the occurrence of child physical abuse? A meta-analysis of global prevalence. International Journal of Psychology 48: 81–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenborgh M, Van Ijzendoorn MH, Euser EM, et al. (2011) A global perspective on child sexual abuse: Meta-analysis of prevalence around the world. Child Maltreatment 16: 79–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan K, Rochani H, Huang LT, et al. (2019) Adverse childhood experiences affect sleep duration for up to 50 years later. Sleep 42: piizsz087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A, Poon L, Kumari V, et al. (2015) Fear biases in emotional face processing following childhood trauma as a marker of resilience and vulnerability to depression. Childhood Maltreatment 20: 240–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taillieu TL, Brownridge DA, Sareen J, et al. (2016) Childhood emotional maltreatment and mental disorders: Results from a nationally representative adult sample from the United States. Childhood Abuse & Neglect 59: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teicher MH, Samson JA. (2013) Childhood maltreatment and psychopathology: A case for ecophenotypic variants as clinically and neurobiologically distinct subtypes. The American Journal of Psychiatry 170: 1114–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thabet AA, Matar S, Carpintero A, et al. (2011) Mental health problems among labour children in the Gaza Strip. Child Care Health Development 37: 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner HA, Finkelhor D, Ormrod R. (2010) Poly-victimization in a national sample of children and youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 38: 323–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh D, McCartney G, Smith M, et al. (2019) Relationship between childhood socioeconomic position and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs): A systematic review. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 73: 1087–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Lowen SB, Anderson CM, et al. (2019) Association of prepubertal and postpubertal exposure to childhood maltreatment with adult amygdala function. JAMA Psychiatry. Epub ahead of print 26 June DOI: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Supplementary_Materials for Childhood maltreatment and its mental health consequences among Indian adolescents with a history of child work by Rakesh Pandey, Shulka Gupta, Aakanksha Upadhyay, Rajendra Prasad Gupta, Meenakshi Shukla, Ramesh Chandra Mishra, Yogesh Kumar Arya, Tushar Singh, Shanta Niraula, Jennifer Yun Fai Lau and Veena Kumari in Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry