Abstract

Introduction:

Many physicians care for patients whose primary spoken language is not English, and these interactions present challenges in physician-patient communication. These challenges contribute to the significant health disparities experienced by populations with limited English proficiency (LEP). Using trained medical interpreters is an important step in addressing this problem, as it improves communication outcomes. Despite this, many medical education programs have little formal instruction on how to work effectively with interpreters.

Methods:

To address this gap, we created an interactive workshop led by professional trained interpreters and faculty facilitators for medical students in their clinical years. Students were asked to evaluate the session based on relevance to their clinical experiences and helpfulness in preparing them for interactions with patients with LEP.

Results:

Immediately after the session, students reported that the clinical scenarios presented were similar those seen on their clinical clerkships. They also reported increased confidence in their ability to work with interpreters. On later follow-up, students reported that the instruction helped prepare them for subsequent patient interactions that involved interpreters.

Conclusion:

A workshop is an effective method for improving medical student comfort and confidence when working with interpreters for populations with LEP.

Keywords: Medical education, medical students, interpreters, interdisciplinary education

Introduction

Health inequity is a major problem in the United States, and the medical community is working to address health disparities in many ways. The root causes of the disparities are numerous. One factor with demonstrable negative impact on the quality of care is poor communication between monolingual English-speaking providers and patients with limited English proficiency (LEP). Providers are often aware of this disparity; in one recent study, a majority of resident physicians in internal medicine, family medicine, and general surgery perceived a lower quality of communication with their patients with LEP compared with English-speaking patients.1

As physicians care for increasingly diverse patient populations, it is essential to find ways to provide high-quality care to all patients. Working with professional interpreters is one technique that has been shown to improve satisfaction of patients with LEP, as well as their understanding during hospitalization.2,3 Evidence suggests that fewer pieces of critical information are missed during hospital discharge when interpreters are involved in the discharge of patients with LEP.4

Given these improvements associated with interpreter use, trained medical interpreters should participate in the care of all patients with LEP in the absence of provider language concordance.5 However, residents acknowledge that they do not consistently engage interpreters for their patients with LEP and cite their own lack of knowledge about access and logistics of using interpreters as a major barrier to consistent use.6 Furthermore, health care providers who regularly work with populations with LEP express the desire for additional formal training on working with interpreters.7

Formal education for trainees and other providers is associated with both increased collaboration with professional interpreters and increased satisfaction with the care the providers are able to provide their patients with LEP.8 Resident satisfaction is higher and frustration is lower when the residents have greater knowledge about working with interpreters.9 Furthermore, medical students given formal teaching sessions reported higher levels of self-efficacy in working with interpreters,10 improvements in knowledge and attitudes about overcoming language barriers,11 and demonstrated improved skills in a simulated clinical setting.12

Despite the evidence that working with interpreters in interactions between English-speaking providers and patients with LEP results in greater satisfaction for both patients and providers, few formal curricula for trainees exist on this topic. At the medical student level, a survey of medical schools suggests that most schools (76% of those that responded) do have some sort of training offered; however, there was a low overall response rate (only 26% of medical schools) making it difficult to interpret. Schools in this study reported a variety of instruction methods including didactic and simulation based, as well as little uniformity as to whether it took place in the pre-clinical or clinical years. In addition, there is little data about the curricular details or the efficacy of specific teaching methods.13 We attempted to address these gaps by engaging medical students in a session focused on working with interpreters that they find both relevant to clinical practice and helpful for developing skills for patient care. Prior to the creation of this session, our students did not receive any formal training from medical school curricula in working with interpreters.

Methods

Third- and fourth-year students in their clinical rotations at the University of Minnesota Medical School all participate in a 1-week course (called Becoming a Doctor) 2 times per academic year. One course component included an in-person workshop session led by a professionally trained medical interpreter and a faculty facilitator. This workshop was a newly developed curriculum that was implemented for the first time in 2018 at the University of Minnesota. The format of the workshop was a small group discussion with 10 to 12 students per group. Material presented included background on the training that interpreters receive including what is involved in becoming certified as well as emphasis on the importance of not using untrained or uncertified interpreters. Additional discussion focused on tips for logistics of working with interpreters in interactions with patients with LEP, case-based examples, and review of student questions about specific clinical scenarios.

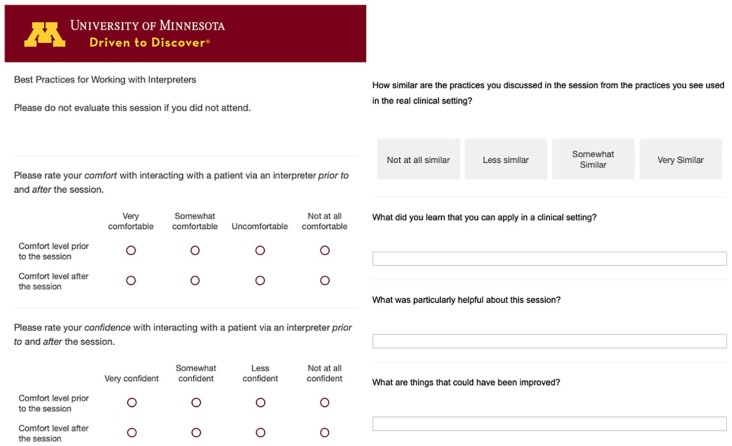

Immediately following the course, students were surveyed (Appendix 1) to assess their perceptions about their comfort working with interpreters and interacting with patients with LEP. They were also asked whether they felt that the information presented was relevant to their clinical experiences.

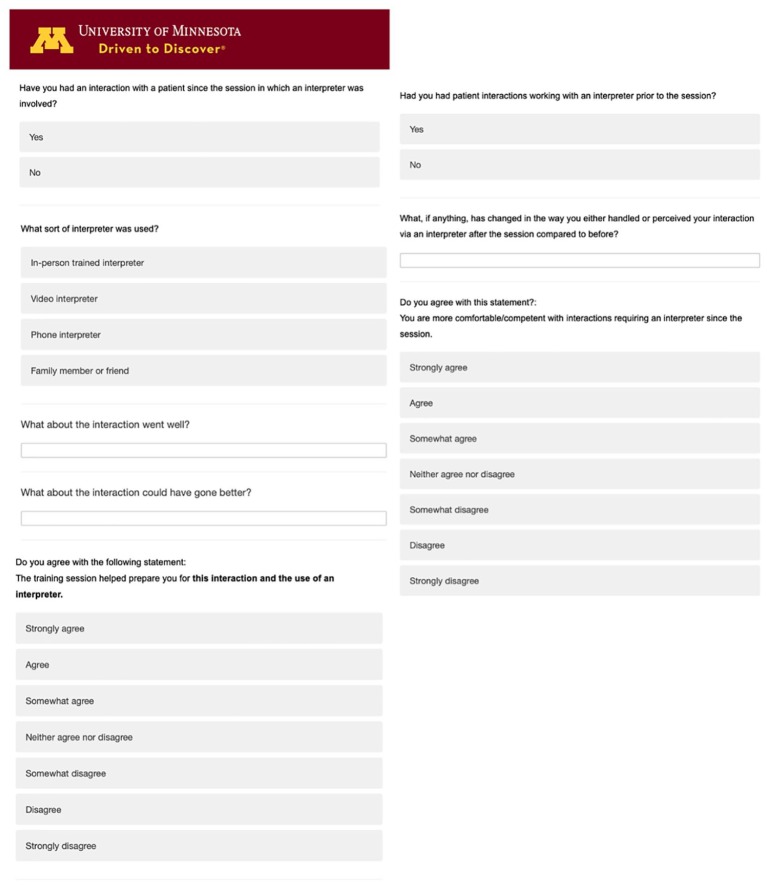

Two months after the sessions, students were invited via email to participate in a follow-up survey (Appendix 2) that asked them to reflect on any interactions they had with patients with LEP and interpreters since the session. Students were asked if the session had changed their comfort, their approach, or their perceived success with the interaction.

Anonymous surveys were designed in Qualtrics© (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) and administered as a link via an email to all enrolled students. To compare continuous data means before and after the intervention, t-tests were performed. Statistical analyses were done using a combination of the Qualtrics software and Microsoft Excel (2017).

The University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board exempted this study from review.

Results

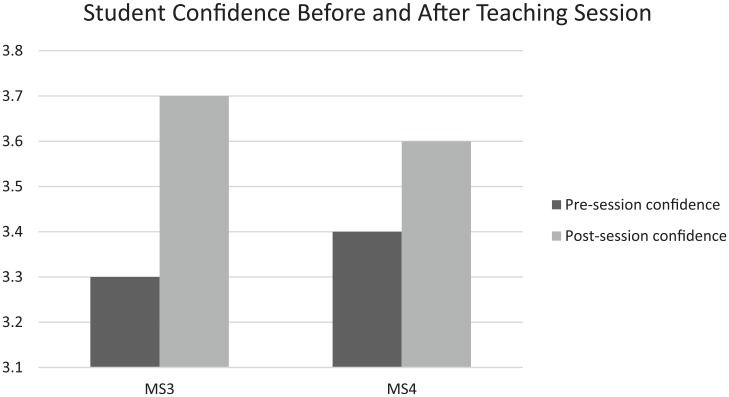

In-person, small group sessions were held for 213 third-year and 213 fourth-year students during the week-long course that all students are required to attend. Of these students, 104 third-year (48.8%) and 115 fourth-year (54.0%) students responded to the initial survey provided immediately after the session. In this initial survey, third-year students reported that their perceived level of confidence in working with an interpreter was higher than before the session. On a 4-point Likert-type scale (with 1 being not at all confident and 4 being very confident), their presession confidence was 3.3 (standard deviation [SD] = 0.59) and their post-session confidence was 3.7 (SD = 0.48; P < .05). Similarly, fourth-year students’ average confidence with an interpreter scenario improved from 3.4 (SD = 0.54) to 3.6 (SD = 0.48) after the session (P < .05; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Student’s reported level of confidence in working with an interpreter before participating in the sessions compared to afterwards, broken up by year in medical school.

The students also evaluated the session scenarios based on relevance to practice (with 1 being not at all similar and 4 being very similar) and rated them a 3.4 out of 4 for similarity to encounters in clinical settings.

Two months after the sessions, follow-up surveys were emailed to all 426 of the student participants. There were 70 students who responded (16.4%). Of those respondents, 59 (84.3%) reported having had a patient encounter that involved an interpreter since the educational intervention. Fifty percent of respondents who reported having worked with interpreters “agree” or “strongly agree” with the statement that the training session helped prepare them for working with an interpreter, and 44.1% indicated that they “agree” or “strongly agree” with a statement that they feel more comfortable/competent afterwards.

Discussion

With growing awareness of the issues preventing health equity, it is increasingly important to develop strategies to address issues leading to disparities in care. A growing body of literature suggests that the use of interpreters during clinical encounters between English-speaking providers and patients with LEP is effective at both improving the patients’ experience2,3 and the providers’ levels of satisfaction with the care they are providing.9 Therefore, increasing the use of interpreters in these situations is one important way that health disparities can begin to be addressed by clinicians at an individual patient level. However, there is limited information regarding how to train providers in best practices surrounding interpreter use, and lack of knowledge remains a significant barrier to regularly working with them in practice.6

This study aimed to address the gap in training through an interactive workshop in which professional medical interpreters taught medical students in the clinical years about the role interpreters play in interactions with patients with LEP. The teaching sessions involved discussion with the interpreter as well as clinical scenarios to provide the students with examples similar to what they might encounter in clinical care. Prior to this session, there had been no formal training on interpreter use in our medical school curriculum. While some students already had some workplace-based experience working with interpreters, many students reported that the session increased their comfort with and confidence in having clinical encounters involving an interpreter. This suggests that formal training may address the topic in a more comprehensive and intentional way than when students simply learn by experience.

Of note, the responses to the 2-month follow-up survey were less clearly positive than expected, with 50% or less respondents stating that the sessions made them more confident. While we still believe there is evidence that the sessions are beneficial, there are a couple of possible considerations as to why this result was obtained. First, it is possible that some students had already received training in another way that made them feel less like they needed this session. It is also possible that for students who had not previously had training were exposed to risks that they had not previously known about which may have led to decreased confidence. These are areas to consider for future assessments of this curriculum.

This study has several limitations. First, this was a survey-based study, and it is possible that respondents viewed the sessions more or less favorably than nonrespondents; furthermore, the respondents’ demographics are not known and this is a possible confounder in our data. In addition, we did not directly measure workplace performance in working with interpreters. Future studies should measure workplace performance (or simulation-based) and address patient perception of the provider, as opposed to only assessing the providers’ perception of their own skills. Other limitations include the lack of knowledge about students’ prior training in this area and the fact that students were not surveyed prior to the session. Finally, we think it would be beneficial to consider correlation with patient outcomes data in an effort to assess if efforts like this can reduce health disparities.

Given that providers who have received training on working with interpreters often report greater satisfaction working with their patients with LEP8 and that most medical students are working with these patients, the inclusion of formal education on interpreter use at the medical student level is an important strategy to improve both patient and provider experience. Including professional interpreters in the instruction appeared to be effective, as many students felt they were better prepared and more comfortable after attending the session.

Medical schools should consider including formal curricula on working with interpreters; it is an effective way to improve student confidence in interactions with patients with LEP using medical interpreters.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the student participants for their input via study surveys and all the interpreter and faculty facilitators who provided this educational experience at the University of Minnesota Medical School. In addition, they thank Hennepin Healthcare for their collaboration.

Appendix

Appendix 1.

Survey provided to students immediately after they attended the educational session. Designed using Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT).

Appendix 2.

Surveys sent to students 2 months after the sessions. Designed using Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT).

Footnotes

Funding:The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: DC wrote the first draft of the paper, designed the surveys, and did initial statistical analyses. AP was involved in designing the curriculum and heavily involved in the process of editing the paper. JS is the Assistant Director of the Becoming a Doctor course, was involved in curriculum and project design, and heavily involved in editing the paper. AO is the Director of the Becoming a Doctor course, was involved in curriculum design, designed the initial research project plans, and was heavily involved in the editing process.

ORCID iD: Donna Coetzee  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5864-8972

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5864-8972

References

- 1. Tang AS, Kruger JF, Quan J, Fernandez A. From admission to discharge: patterns of interpreter use among resident physicians caring for hospitalized patients with limited English proficiency. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2014;25:1784-1798. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2014.0160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anttila A, Rappaport DI, Tijerino J, Zaman N, Sharif I. Interpretation modalities used on family-centered rounds: perspectives of Spanish-speaking families. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7:492-498. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2016-0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zurca AD, Fisher KR, Flor RJ, et al. Communication with limited English-proficient families in the PICU. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7:9-15. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2016-0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gutman CK, Cousins L, Gritton J, et al. Professional interpreter use and discharge communication in the pediatric emergency department. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18:935-943. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2018.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ortega P, Perez N, Robles B, Turmelle Y, Acosta D. Strategies for teaching linguistic preparedness for physicians: medical Spanish and global linguistic competence in undergraduate medical education. Health Equity. 2019;3:312-318. doi: 10.1089/heq.2019.0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sandler R, Myers L, Springgate B. Resident physicians’ opinions and behaviors regarding the use of interpreters in New Orleans. South Med J. 2014;107:698-702. doi: 10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Watts KJ, Meiser B, Zilliacus E, et al. Perspectives of oncology nurses and oncologists regarding barriers to working with patients from a minority background: systemic issues and working with interpreters. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2018;27:e12758. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Karliner LS, Pérez-Stable EJ, Gildengorin G. The language divide. The importance of training in the use of interpreters for outpatient practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:175-183. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15009797. Accessed September 27, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hernandez RG, Cowden JD, Moon M, Brands CK, Sisson SD, Thompson DA. Predictors of resident satisfaction in caring for limited English proficient families: a multisite study. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14:173-180. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McEvoy M, Santos MT, Marzan M, Green E, Milan F. Teaching medical students how to use interpreters: a three year experience. Med Educ Online. 2009;14:12. doi: 10.3885/meo.2009.Res00309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jacobs EA, Diamond LC, Stevak L. The importance of teaching clinicians when and how to work with interpreters. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78:149-153. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shriner CJ, Hickey DP. Teaching and assessing family medicine clerks’ use of medical interpreters. Fam Med. 2008;40:313-315. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18465276. Accessed September 27, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Himmelstein J, Wright WS, Wiederman MW. U.S. medical school curricula on working with medical interpreters and/or patients with limited English proficiency. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2018;9:729-733. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S176028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]