Abstract

PURPOSE

Conventional clinic blood pressure (BP) measurements are routinely used for hypertension management and physician performance measures. We aimed to check home BP measurements after elevated conventional clinic BP measurements for which physicians did not intensify treatment, to differentiate therapeutic inertia from appropriate inaction.

METHODS

We conducted a pre and post study of home BP monitoring for patients with uncontrolled hypertension as determined by conventional clinic BP measurements for which physicians did not intensify hypertension management. Physicians were notified of average home BP 2-4 weeks after the initial clinic visit. Outcome measures were the proportion of patients with controlled hypertension using average home BP measurements, changes in hypertension management by physicians, changes in physicians’ hypertension metrics, and factors associated with home-clinic BP differences.

RESULTS

Of 90 recruited patients who had elevated conventional clinic BP recordings, 65.6% had average home BP measurements that were <140/90 mm Hg. Physicians changed treatment plans for 61% of patients with average home BP readings of ≥140/90 mm Hg, whereas decisions to not change treatment for the remaining patients were based on contextual factors. Substituting average home BP for conventional clinic BP for 4% of patients from 2 physicians’ hypertension registries improved the physicians’ hypertension control rates by 3% to 5%. Greater body mass index and increased number of BP medications were associated with home BP measurement ≥140/90 mm Hg. Clinic BP levels did not estimate normal home BP levels.

CONCLUSIONS

Documented home BP in cases of clinical uncertainty helped differentiate therapeutic inertia from appropriate inaction and improved physicians’ hypertension metrics.

Key words: blood pressure monitoring, home, clinician inertia, hypertension, white coat, patient care management/standards

INTRODUCTION

Conventional clinic blood pressure (BP) measurements are often inaccurate and distinct from time-consuming, research-quality, clinic BP measurements, which are used for clinical practice guideline development.1–6 Blood pressure is a continuous value with natural variations throughout the day, and repeated measurements over time are generally more accurate in establishing a diagnosis of hypertension.1,7,8 However, conventional clinic BP is routinely used for hypertension diagnosis, management, and physician performance measures. Evidence shows that home BP measurements are more accurate than clinic BP measurements, and the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends the use of ambulatory or home BP readings for the diagnosis of hypertension.9 The Controlling High Blood Pressure quality metric for the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), however, does not allow home BP use for metric calculations; it uses the final clinic BP recording during the 12-month measurement period and assumes hypertension is uncontrolled if there are no readings in the measurement period.10 Using a single clinic BP value for hypertension management decisions or to measure physician performance is inappropriate because it does not reflect patients’ true BP or physicians’ true quality of care.1,4–6

Physicians and patients are reluctant to intensify treatment when they are convinced that elevated clinic BP is not reflective of true BP control status.11–13 White coat BP elevation assessed by normal home BP measurements when clinic BP measurements are high is not a cardiovascular disease risk factor for patients treated for hypertension.14 Therapeutic inertia, which is a physician’s failure to increase therapy when treatment goals are unmet, is commonly reported as one of the contributing factors for the high prevalence of uncontrolled hypertension.15 Treatment decisions between physicians and patients, however, are highly individualized and complex. Not intensifying treatment is appropriate inaction if the elevated BP is not confirmed, there is an increased risk of treatment for the patient, or there are medication adherence or affordability issues.16 No prior studies have assessed appropriate inaction vs therapeutic inertia when there is a documented high conventional clinic BP, and no change in BP management is presumed necessary by the physician or the patient owing to clinical uncertainty about the BP reading.16,17 A telemonitoring study assessed physician reactions to elevated home BP and found that physicians did not intensify treatment when home BP was close to an acceptable threshold, indicating good clinical judgment.18 All prior studies of therapeutic inertia used research-quality clinic BP measurements or 24-hour ambulatory BP measurements for BP outcome measurement.19 No home BP study has used home BP measurements to measure primary BP outcomes, hypertension control rates, and BP management decisions when conventional clinic BP was elevated and physicians did not intensify treatment.

We focused on home BP monitoring for patients with elevated clinic BP measurements who did not receive treatment intensification. The aims of this pilot study were to (1) determine if treatment nonintensification is due to clinical uncertainty or therapeutic inertia; (2) determine if clinical certainty, BP management, and physicians’ hypertension metrics could be improved by integrating home BP readings into electronic health records (EHRs); (3) identify variables associated with elevated average home BP; and (4) survey patients for recommendations on how to best integrate home BP measurements into clinical practice.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a single-group pre and post assessment of hypertensive patients with uncontrolled hypertension according to clinic BP measurement and no change in BP management at a recent visit and in the previous month. Patients were recruited from 2 Mid-west, urban, academic family medicine clinics from October 2017 to February 2018. We calculated that a sample size of 87 patients would provide 80% power to detect a 10% difference in the main outcome of controlled hypertension by home BP vs uncontrolled hypertension by clinic BP using paired proportions, assuming a 50% correlation with a 2-tailed alpha of .05. We inflated the sample size by 10% to 96 to allow for dropouts and invalid BP measurements.

Patient Recruitment

Clinic staff gave patients a study flier if their clinic BP reading was ≥140/90 mm Hg, and patients were directed to research assistants after their clinic visit (Supplemental Figure 1, http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/18/1/50/suppl/DC1/). At recruitment, research assistants used a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention checklist of recommended tasks for BP self-measurement.20 Research assistants demonstrated the proper home BP measurement technique to each participant, followed by participants demonstrating the technique. During the demonstration, participants were required to complete all of the recommended tasks on the checklist to be eligible for recruitment (Supplemental Appendix 1, http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/18/1/50/suppl/DC1/). Fliers from the American Heart Association on proper home BP measurement technique were also given to each patient. Home BP monitors (Omron 10 series 786N with self-adjusting cuff [Omron Healthcare, Inc]) were loaned to patients, with instructions to check their BP twice daily at different times, at their convenience. A checklist of proper home BP measurement tasks was attached to each home BP monitor case. Patients returned the BP monitor 2 weeks later, after checking BP at least 12 times over a minimum period of 7 days.

At the 2-week follow-up, a task-completion list was used to check whether patients used the home BP monitor accurately (Supplemental Appendix 1). If patients did not meet the required tasks on the checklist, their home BP readings were considered invalid and not entered in the EHR. These patients had the option to perform home BP measurements for an additional 2 weeks. For patients with ≥12 recorded home BP readings over a minimum period of 7 days and who demonstrated accurate BP measurement technique at the follow-up, the average home BP was calculated after excluding first-day readings and was documented in the patient’s EHR (Supplemental Figure 2, http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/18/1/50/suppl/DC1/). Research assistants sent the average home BP readings to the patient’s primary care physician via a secure EHR message for endorsement and then tracked the home BP message in the EHR and extracted physician responses. In addition, clinic BP at a subsequent clinic visit and any changes in BP management in all messages and at all clinic visits were tracked by chart review 4 to 6 months later. We assessed the change in the proportion of patients with uncontrolled hypertension according to clinic BP measurement, and when the average home BP showed controlled hypertension, at a subsequent clinic visit. We added this step to assess the suitability of the latest conventional clinic BP measurement for calculating hypertension metrics for MIPS when a valid home BP measurement is documented in EHR in the prior 6 months. Research assistants also extracted and coded physician recommendations based on home BP measurements for lifestyle changes, medication adherence, medication changes, or no changes. Research assistants reviewed physician notes for patients who had controlled hypertension according to home BP measurement and a subsequent clinic visit with uncontrolled hypertension and extracted any change in BP management at the subsequent clinic visit.

Chart Abstraction for Variables Predicting Clinic-Home Blood Pressure Differences

Chart abstractions included patient demographics, BP measurements (ie, initial clinic BP values, number of clinic BP measurements taken, outpatient clinic BP documented in the EHR 4 to 6 months after average home BP measured), number of BP medications, total medications including over-the-counter medications, chronic medical problems, presence/absence of medication adverse effects, presence/absence of mood disorders, number of emergency/urgent care visits and hospitalizations in the prior 12 months, and geographic distance to patient’s residence from the primary care physician’s clinic.

Patients were also asked to complete a survey that included adverse effects of BP-lowering medications, history of lightheadedness in the past month, smoking status, and the presence/absence of a mood disorder. Furthermore, a poststudy survey of patients was conducted to assess their preferred method of home BP monitoring education, willingness to pay for home BP monitors, feasible home BP monitoring frequency, preferred mode of home BP communication with their physician, and recommendations for home BP use in clinical practice. Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Self-Efficacy for Managing Medications and Treatments scale scores were also collected.21 This study was approved by the University of Missouri Institutional Review Board.

ANALYSIS

Descriptive statistics were examined for all participant characteristics and study outcomes including pre- and poststudy survey and BP measurement data. Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) core health measure sets and reports from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) have not specified separate targets for home BP readings. Therefore, we set our home BP goal to <140/90 mm Hg on the basis of the JNC 8 panel member report and MACRA measures.22,23 With the use of average home BP measurements from 2 to 4 weeks after the clinic visit, patients were grouped into 1 of 2 categories: hypertension uncontrolled (BP ≥140/90 mm Hg) and hypertension controlled (BP <140/90 mm Hg). To examine differences between the patients with controlled vs uncontrolled hypertension after home BP measurements, c2 analyses (or t tests for continuous variables) were used. To extrapolate the effect of home BP documentation on hypertension control rates for our department, we applied the percentage of patients with controlled hypertension according to home BP measurements from our results to the total number of patients with uncontrolled hypertension in our department’s hypertension registry. All quantitative analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc).

For qualitative analysis of open-ended questions in our survey, 2 authors independently coded the responses, which were then verified by a third coder. Coders met in person to examine each survey coding, analyzed responses to the open-ended questions for common themes, and performed thematic analysis using Dedoose software (SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC).

RESULTS

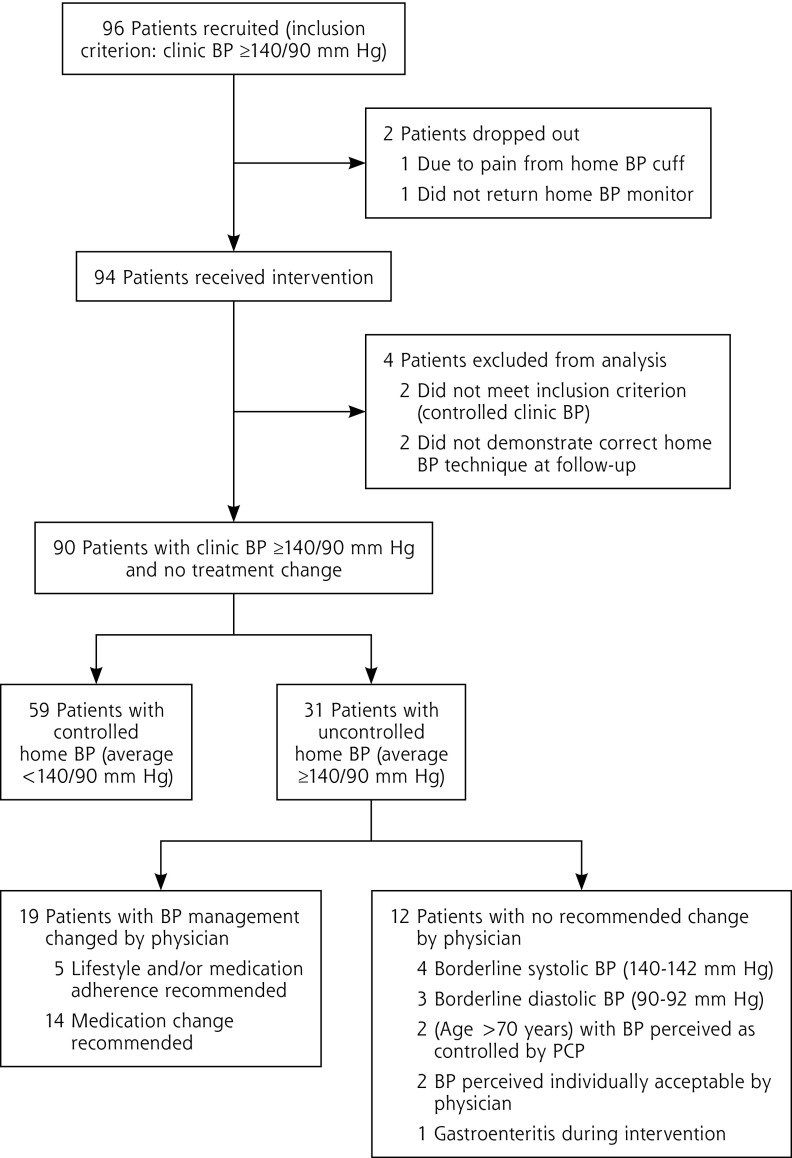

A total of 96 patients who had a clinic BP ≥140/90 mm Hg were recruited for this study. Two patients dropped out of the study because they had issues with the BP monitor equipment, leaving 94 who received the intervention. After the study started, 4 additional patients were excluded from further analysis because it was discovered that they had a clinic BP that did not fit the criterion of the study (n = 2) or used improper BP technique when using the BP monitors (n = 2), leaving 90 patients who remained in the study (see Figure 1 for a participant flow diagram and outcomes). Of the 90 patients included in the final analysis, 65.6% had controlled hypertension (home BP <140/90 mm Hg), whereas 34.4% had uncontrolled hypertension (home BP ≥140/90 mm Hg) (Table 1). The median systolic clinic BP for all of the participants was 154.5 mm Hg, and the median diastolic BP was 92 mm Hg (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Participant flow diagram.

BP = blood pressure; PCP = primary care physician.

Table 1.

Sample Demographics, Overall and by Controlled and Uncontrolled Average Home BP Measurement

| Home Blood Pressure

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Controlled (<140/90 mm Hg) | Uncontrolled (≥140/90 mm Hg) | P Value | |

| Overall, No. (%) | 90 (100.0) | 59 (65.6) | 31 (34.4) | … |

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 61.7 (13.1) | 61.4 (12.0) | 62 (14.8) | .75 |

| <50, No. (%) | 22 (22.2) | 16 (22.0) | 7 (22.6) | |

| 51-65, No. (%) | 24 (26.6) | 16 (27.1) | 8 (25.8) | |

| ≥66, No. (%) | 46 (51.1) | 30 (50.8) | 16 (51.6) | |

| Sex, No. (%) | .34 | |||

| Male | 49 (54.4) | 30 (50.8) | 19 (61.3) | |

| Female | 41 (45.6) | 29 (49.2) | 12 (38.7) | |

| Race, No. (%) | .80 | |||

| African American/black | 9 (10.0) | 5 (8.5) | 4 (12.9) | |

| Caucasian/white | 75 (83.3) | 50 (84.7) | 25 (80.6) | |

| Other | 6 (6.7) | 4 (6.8) | 2 (6.4) | |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 29.2 (6.1) | 28 (5.7) | 31.5 (6.5) | .01 |

| Education, No. (%) | .52 | |||

| High school diploma/GED or less | 15 (16.7) | 11 (18.6) | 4 (12.9) | |

| Some college/2-year college degree | 25 (27.8) | 18 (30.5) | 7 (22.6) | |

| 4-Year college degree/postgraduate work | 24 (26.7) | 13 (22.0) | 11 (35.5) | |

| Postgraduate degree | 26 (28.9) | 17 (28.8) | 9 (29.0) | |

| Smoking status (chart review), No. (%) | .27 | |||

| Current smoker | 6 (6.7) | 5 (8.5) | 1 (3.2) | |

| Former smoker (last smoked >2 months) | 30 (33.3) | 17 (28.8) | 13 (41.9) | |

| Never smoker | 52 (57.8) | 37 (62.7) | 15 (48.4) | |

| Home BP readings, mean (SD) | ||||

| Home BP readings, total | 73 (21.4) | 72.1 (22.4) | 74.9 (19.5) | .55 |

| Days from first to last home BP reading | 14.1 (3.6) | 14.2 (3.6) | 14 (3.7) | .76 |

| Cardiovascular diseasesa (chart review), No. (%) | ||||

| Cardiovascular disease absent | 47 (52.3) | 27 (45.8) | 20 (64.5) | .09 |

| Cardiovascular disease present | 43 (47.7) | 32 (54.2) | 11 (35.5) | |

| Medications (self-reported) | ||||

| Total number OTC medications, mean (SD) | 1.8 (1.5) | 1.6 (1.4) | 2.1 (1.6) | .06 |

| Report of lightheadedness, No. (%) | 18 (20.0) | 13 (22.0) | 5 (16.1) | .75 |

| Medications (chart review) | ||||

| Dietary supplements | 42 (46.7) | 24 (40.7) | 18 (58.1) | .11 |

| Psychoactive | 26 (28.9) | 17 (28.8) | 9 (29.0) | .98 |

| Nonopioid | 36 (40.0) | 20 (33.9) | 16 (51.6) | .10 |

| Opioid | 14 (15.6) | 10 (16.9) | 4 (12.9) | .61 |

| Levothyroxine | 12 (13.3) | 8 (13.6) | 4 (12.9) | .93 |

| Allergy | 12 (13.3) | 4 (6.8) | 8 (25.8) | .01 |

| Total number of BP medications, mean (SD) | 1 (0.9) | 0.8 (0.8) | 1.4 (1.1) | .01 |

| Total number of medications, mean (SD) | 4.4 (2.9) | 3.8 (2.7) | 5.4 (3.1) | .01 |

| PROMIS scales (postsurvey) | ||||

| Adherence raw score, mean (SD) | 34.9 (4.4) | 35 (4.8) | 34.8 (4) | .97 |

| Adherence T-score, mean (SD)b | 48.7 (7.5) | 49 (7.8) | 48 (6.9) | .77 |

| Low, No. (%) | 11 (21.6) | 7 (25.0) | 4 (20.0) | … |

| Moderate, No. (%) | 29 (56.9) | 16 (57.1) | 13 (65.0) | … |

| High, No. (%) | 8 (17.6) | 5 (17.9) | 3 (15.0) | … |

BMI = body mass index; BP = blood pressure; GED = General Educational Development; OTC = over the counter; PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System.

Notes: P values based on c2 comparison (t test for continuous variables), by controlled vs uncontrolled. For the conrolled vs uncontrolled comparisons, column percentages are presented, unless noted, as a continuous outcome (mean, SD).

Cardiovascular diseases: coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, arrhythmia, heart valve disorder, heart failure, peripheral artery disease.24

Adherence t scores grouped into low (>1 SD below mean), moderate (values within 1 SD above/below mean), and high (>1 SD above mean).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Clinic and Home BP

| Mean (SD) Minimum | Maximum | Median | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinic BP (prestudy), mm Hg | ||||

| Systolic (n = 90) | 158 (14) | 131 | 207 | 154.5 |

| Diastolic (n = 90) | 91 (12) | 63 | 132 | 92 |

| Home BP (average), mm Hg | ||||

| Systolic (n = 90) | 133 (10) | 107 | 158 | 133.5 |

| Diastolic (n = 90) | 81 (8) | 63 | 99 | 82 |

| Clinic BP (poststudy)a, mm Hg | ||||

| Systolic (n = 70) | 148 (18) | 111 | 195 | 149.5 |

| Diastolic (n = 70) | 85 (11) | 60 | 112 | 86 |

| Prestudy clinic BP cutoff point | Home BP<140/90 mm Hg,No. (%) | |||

|

|

||||

| <160/95 mm Hg (n = 39) | 25 (64.1) | |||

| >160/95 mm Hg (n = 51) | 34 (66.7) | |||

| <155/92 mm Hg (n = 32) | 22 (68.8) | |||

| >155/92 mm Hg (n = 58) | 37 (63.8) | |||

BP = blood pressure.

Poststudy sample size differed due to missing data (not all 90 patients had a 6-month follow-up visit).

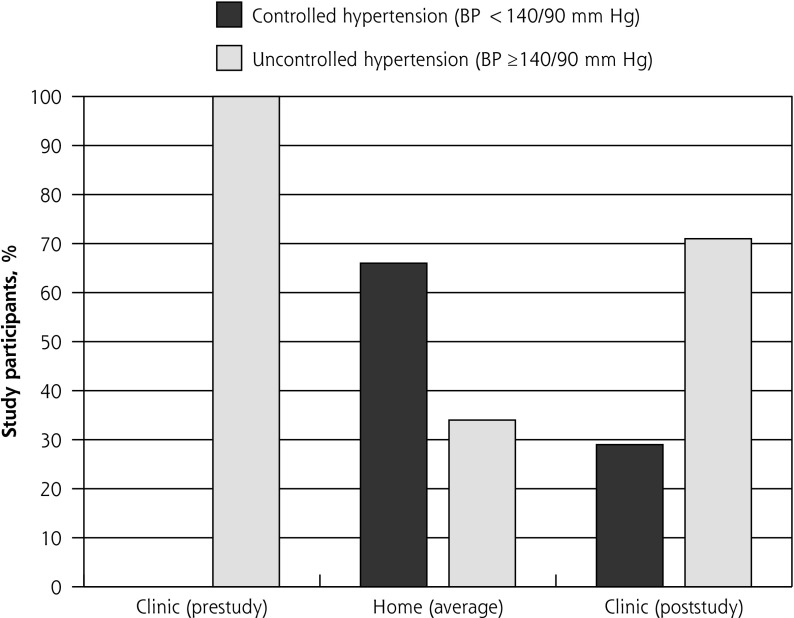

Clinic BP did not estimate who would have home BP readings <140/90 mm Hg (Table 2). Of patients who exceeded a greater clinic BP cutoff of 160/95 mm Hg, 66.7% had home BP measurements <140/90 mm Hg. Poststudy clinic BP measurements documented via EHR 4 to 6 months after home BP measurements showed a decrease in the proportion of patients with controlled hypertension, from 66% to 29%, compared with home BP measurements (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Blood pressure values.

BP = blood pressure.

Effect on Providers’ Hypertension Metrics

Two physicians referred more than 10 patients to our study. One physician’s hypertension control rate increased by 3% (66% to 69%) when clinic BP was replaced by average home BP for their 14 enrolled patients (of 343 patients with hypertension). The second physician’s hypertension control rate increased by 5% (50% to 55%) for their 13 enrolled patients (of 278 patients with hypertension). Changing 66% (59 of 90) of patients with uncontrolled hypertension in our department registry to expected controlled hyper tension by home BP measurement increased the department’s hypertension control rate from 58% to 86%.

Variables Associated With Clinic-Home Blood Pressure Differences

Characteristics associated with average home BP ≥140/90 mm Hg are shown in Table 1.

Physician Response to Average Home Blood Pressure Noted in Electronic Health Records

Lifestyle changes, medication changes, and/or medication adherence were recommended by physicians for 19 of the 31 (61%) patients with average home BP ≥140/90 mm Hg, whereas elevated home BP was considered individually acceptable for the remaining 12 patients (Figure 1 and Supplemental Table 1, http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/18/1/50/suppl/DC1/). A total of 20 patients with controlled hypertension according to home BP measurement had uncontrolled hypertension according to clinic BP measurement at a subsequent clinic visit, and physicians did not change BP management for 18 of those patients and reduced BP medication dose for 2 patients. A majority of physicians specifically mentioned recent normal home BP as a reason for not changing BP management despite uncontrolled hypertension according to subsequent clinic BP measurement.

Postintervention Survey Results

A total of 70 of 90 patients (78% response rate) completed the post-intervention survey. Results showed that 89% (31 of 35) of patients who owned a home BP monitor before intervention and 51% (18 of 35) of patients who did not own a home BP monitor planned to continue regularly checking their BP at home (Supplemental Table 2, http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/18/1/50/suppl/DC1/). A total of 83% of patients who did not own a home BP monitor stated that they would consider buying one if their insurance would reimburse them. Feasible frequencies for checking home BP were twice a day or less. Thematic analysis of open-ended questions showed that home BP monitoring enhanced patients’ understanding of their factual BP control and willingness to add medications and promoted behavior changes (Table 4).

Table 4.

Thematic Analysis of Qualitative Data

| Theme | Quote | |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral changes | ||

| Healthier options | “I am increasingly controlling the type of food I eat during the day.” | |

| Less salt | “Reduce salt intake because one day I ate a small pack of pretzels inthe evening. My BP at the usual monitoring time (which was ~1.5hour of eating the pretzel) was noticeably higher than other days.So I am consciously trying to reduce the amount of salt especiallyfrom processed foods.” | |

| Physical activity | “I am getting more regular exercise.”“Increased frequency and intensity of exercise” | |

| Practice relaxation | “I love to meditate and I found that it had a direct effect on my BP - or seemed to.”“Yoga 3 or 4 times a week” | |

| Patients’ awareness of BP control status | ||

| Realized BP truly uncontrolled | “I thought it was better controlled, but realized it was not.”“As a result of the study findings my doctor has added a medication to better control my BP.” | |

| Reassured BP controlled | “I found out that I do NOT have high blood pressure. When I’m in the clinic it is sky high. When I am at home, it is normal. I’d like to get off my medicine then test it at home to see if I need to stay on the low dose or not.” | |

| Recommendations for clinic | ||

| Arm support while measuring BP at clinic | “Second, and relatively easily achievable, providing something for the tested arm to rest on at a correct height while the reading is being taken.” | |

| BP measurement at the end of the visit | “Don’t take blood pressure reading immediately upon entering the exam room! There is talking, moving around, no chance to sit quietly, and anxiety about the visit. Wait for physician consult to conclude, allow patient 10 minutes to sit quietly, then take the reading. Alternatively, put patient in room for 10 minutes with instructions before taking blood pressure.” | |

| Use average of multiple reading for diagnosis | “My blood pressure fluctuates within minutes. I do not think you can assess what someone’s average blood pressure reading is by one or two readings. My blood pressure was 109/66 this morning. Just 6 months ago a cardiologist put me on high blood pressure medicine (which made me very sick) because my readings were high in the office. I think doctors need to study their patients’ general health in more detail before issuing these strong medicines.” | |

BP = blood pressure.

DISCUSSION

We found that 65.6% of clinic BP readings ≥140/90 mm Hg were not supported by home BP measurements, and extrapolation of our findings increased our department’s hypertension control rate by 28%. We did not identify any clinic BP cutoff value below which average home BP was more likely to be <140/90 mm Hg. Clinic BP readings documented a few months after home BP measurements continued to show a greater percentage of patients with uncontrolled hypertension compared with home BP readings. Despite our clinic policy of repeating clinic BP measurement, clinic BP was checked only once during the clinic visit for 79% of the recruited patients, twice for 19% of patients, and 3 times for 2% of patients.

Physicians did not intensify management despite higher average home BP for 12 patients, given contextual factors such as borderline BP elevations of 2 mm Hg and older age. This inaction is appropriate cautiousness because older individuals taking antihypertensive medication and who have complex health problems and/or frailty might experience cognitive decline at lower BP levels.25,26 In addition, the absolute effect of antihypertensive treatments on cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality in adults with mild hypertension is minimal.27–29 Overall, 21% of all our recruited patients needed a change in BP management, which included lifestyle changes and/or improved medication adherence recommendations, with only 16% needing a change in medication. Patients reported incorrect clinic BP measurement techniques in our postintervention survey, which is consistent with the literature.2,3

Hypertension guidelines and physician performance measures have not considered the impact of conventional clinic BP measurements on BP thresholds for hypertension treatment. In the present study, 16 patients had systolic clinic BP >170 mm Hg, and 10 of those patients had average home BP <140/90 mm Hg. Certain guidelines recommend a home BP threshold of <135/85 mm Hg and a clinic BP threshold of <140/90 mm Hg for a hypertension diagnosis.30 Hypertension guidelines are based on research-quality BP measurements for which BP is measured, repeated, and calculated under ideal conditions.31,32 Not intensifying treatment is appropriate cautiousness rather than therapeutic inertia in situations of clinical uncertainty.33 In addition, performance measures calculated by easily measured intermediate endpoints with binary thresholds, such as BP, do not account for the complex individualized patient-centered care provided by primary care physicians.34 Treatment based on overall CVD risk instead of BP threshold would have fewer people on medication, with similar reductions in CVD events at every BP level.35

Measurement, documentation, and use of average home BP measurements in cases of clinical uncertainty would improve BP management and accuracy of hypertension control rates. This is important because ambulatory BP monitoring and interpretation is covered by Medicare Part B for the diagnosis of white coat hypertension, whereas home BP monitoring or clinician interpretation of home BP results is not covered by Medicare.22 Ambulatory BP monitoring is currently not broadly available, performed, or adequately reimbursed.36–38 We acknowledge that increasing the number of clinic- and EHR-related tasks, such as collecting, calculating, and documenting average home BP in the EHR, with no increase in the time allotted for patient visits will contribute to increased time pressure for physicians because hypertension is rarely the only reason for a clinic visit.39,40

There are several concerns regarding the use of home BP measurement that might preclude its use for hypertension metrics. First, home BP monitors can be inaccurate; however, physicians can provide patients with a list of locally available, validated home BP monitors (Supplemental Appendix 2, http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/18/1/50/suppl/DC1/)). Second, inaccurate home BP measurement technique might result in erroneous BP measurement. However, participants mentioned frequent inaccurate clinic BP measurement technique in our poststudy survey, and we continue to use clinic BP values for hypertension metrics. Patients can be educated on proper home BP monitoring technique by clinic staff and by using handouts and available online educational videos (Supplemental Appendix 2). Third, there are concerns that patients might report incorrect home BP readings; however, most home BP devices store multiple readings, and the patient can be instructed to bring the home BP monitor to every visit. Self-reports of smoking, alcohol use, quality of life, and depression screens are routinely used to guide treatment decisions; similarly, patient-reported home BP should be trusted to encourage patient engagement. As an example, patients with high home BP measurements in the present study acknowledged that their hypertension was truly uncontrolled and were willing to add medication (Table 4).

Insurance coverage of home BP monitor costs might encourage home BP monitoring.41,42 Loaning of validated home BP monitors is underused in clinical practice and might help overcome home BP monitor cost barriers for patients and reduce the use of unreliable home BP monitors.43

Limitations

One limitation of the present study is that we did not include patients with normal BP measured in clinic; hence, we may have missed detecting masked hypertension. Masked hypertension is rarely reported by patients because elevated BP usually has no symptoms, and there are no defined clinic BP cutoff levels recommended to screen for masked hypertension.44,45 Also, there are no data on whether treating masked hypertension reduces CVD mortality.46 Although clinic BP can be falsely high or low, falsely high clinic BP has substantial consequences because it mislabels controlled hypertension as uncontrolled, exposing those patients to increased medical costs and potential adverse effects.26,47–49 We examined large number of variables for association with uncontrolled hypertension by home BP measurements, which may increase the chances of detecting false positive associations. The majority of the patients in this study were college educated, and therefore home BP monitoring compliance might have been high compared with other populations.

CONCLUSIONS

The present study showed that clinic BP was falsely high for two-thirds of patients for whom physicians did not change BP management, with only 16% of patients requiring a change in medication. Physician BP management decisions in the present study reflected appropriate inaction and not therapeutic inertia, on the basis of BP trustworthiness and individualized treatment goals. Most validated home BP values should be accepted and preferred for physician hypertension performance measures. Hypertension metrics and guidelines need to be adjusted for conventional clinic BP measurements.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: authors report none.

To read or post commentaries in response to this article, see it online at http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/18/1/50.

Funding support: Funding was received from the AAFP Foundation as a Practice Based Research Network Stimulation award. S.J.P was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number KL2 TR002346 during this manuscript preparation. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This publication was supported in part by NIH/NIDDK P30DK092950 Washington University Center for Diabetes Translation Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the NIDDK.

Previous presentation: Some of the findings from this article were presented at the North American Primary Care Research Group (NAP-CRG) conference; November 9-13, 2018; Chicago, Illinois.

Supplementary materials: Available at http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/18/1/50/suppl/DC1/.

References

- 1.Burkard T, Mayr M, Winterhalder C, Leonardi L, Eckstein J, Vischer AS. Reliability of single office blood pressure measurements. Heart. 2018; 104(14): 1173–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhatt H, Siddiqui M, Judd E, Oparil S, Calhoun D. Prevalence of pseudoresistant hypertension due to inaccurate blood pressure measurement. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2016; 10(6): 493–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Minor DS, Butler KR, Jr, Artman KL, et al. Evaluation of blood pressure measurement and agreement in an academic health sciences center. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2012; 14(4): 222–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Myers MG, Godwin M, Dawes M, Kiss A, Tobe SW, Kaczorowski J. Measurement of blood pressure in the office: recognizing the problem and proposing the solution. Hypertension. 2010; 55(2): 195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levy J, Gerber LM, Wu X, Mann SJ. Nonadherence to recommended guidelines for blood pressure measurement. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016; 18(11): 1157–1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sebo P, Pechère-Bertschi A, Herrmann FR, Haller DM, Bovier P. Blood pressure measurements are unreliable to diagnose hypertension in primary care. J Hypertens. 2014; 32(3): 509–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Final recommendation statement: high blood pressure in adults: screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/high-blood-pressure-in-adults-screening. Published 2016. Updated Nov 2016 Accessed Jul 19, 2017.

- 8.Powers BJ, Olsen MK, Smith VA, Woolson RF, Bosworth HB, Odd-one EZ. Measuring blood pressure for decision making and quality reporting: where and how many measures? Ann Intern Med. 2011; 154(12): 781–788, W-289–W-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siu AL, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Screening for high blood pressure in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015; 163(10): 778–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quality Payment Program, U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Department of Health and Human Services Explore measures and activities. https://qpp.cms.gov/mips/explore-measures/quality-measures. Published 2018 Accessed Aug 16, 2018.

- 11.Kerr EA, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Klamerus ML, Subramanian U, Hogan MM, Hofer TP. The role of clinical uncertainty in treatment decisions for diabetic patients with uncontrolled blood pressure. Ann Intern Med. 2008; 148(10): 717–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Safford MM, Shewchuk R, Qu H, et al. Reasons for not intensifying medications: differentiating “clinical inertia” from appropriate care. J Gen Intern Med. 2007; 22(12): 1648–1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Viera AJ, Tuttle LA, Voora R, Olsson E. Comparison of patients’ confidence in office, ambulatory, and home blood pressure measurements as methods of assessing for hypertension. Blood Press Monit. 2015; 20(6): 335–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stergiou GS, Asayama K, Thijs L, et al. International Database on HOme blood pressure in relation to Cardiovascular Outcome (IDHOCO) Investigators Prognosis of white-coat and masked hypertension: International Database of HOme blood pressure in relation to Cardiovascular Outcome. Hypertension. 2014; 63(4): 675–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okonofua EC, Simpson KN, Jesri A, Rehman SU, Durkalski VL, Egan BM. Therapeutic inertia is an impediment to achieving the Healthy People 2010 blood pressure control goals. Hypertension. 2006; 47(3): 345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lebeau JP, Biogeau J, Carré M, et al. Consensus study to define appropriate inaction and inappropriate inertia in the management of patients with hypertension in primary care. BMJ Open. 2018; 8(7): e020599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lebeau JP, Cadwallader JS, Aubin-Auger I, et al. The concept and definition of therapeutic inertia in hypertension in primary care: a qualitative systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2014; 15: 130–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crowley MJ, Smith VA, Olsen MK, et al. Treatment intensification in a hypertension telemanagement trial: clinical inertia or good clinical judgment? Hypertension. 2011; 58(4): 552–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agarwal R, Bills JE, Hecht TJ, Light RP. Role of home blood pressure monitoring in overcoming therapeutic inertia and improving hypertension control: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2011; 57(1): 29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Self-measured blood pressure monitoring: action steps for clinicians. https://millionhearts.hhs.gov/files/MH_SMBP_Clinicians.pdf. Published 2014 Accessed Oct 3, 2016.

- 21.Gruber-Baldini AL, Velozo C, Romero S, Shulman LM. Validation of the PROMIS measures of self-efficacy for managing chronic conditions. Qual Life Res. 2017; 26(7): 1915–1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Core Measure Sets MACRA SMA Informatics. https://qpp.cms.gov/docs/QPP_quality_measure_specifications/CQM-Measures/2019_Measure_236_MIPSCQM.pdf. Published 2016. Updated May 5, 2016 Accessed Oct 25, 2016.

- 23.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). Erratum: JAMA. 2014; 311(5): 507–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Know the differences: cardiovascular disease, heart disease, coronary heart disease. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/publications/Fact_Sheet_Know_Diff_Design.508_pdf.pdf. Published 2019 Accessed Jun 6, 2019.

- 25.Streit S, Poortvliet RKE, Elzen WPJD, Blom JW, Gussekloo J. Systolic blood pressure and cognitive decline in older adults with hypertension. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(2):100–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mossello E, Pieraccioli M, Nesti N, et al. Effects of low blood pressure in cognitively impaired elderly patients treated with antihypertensive drugs. JAMA Intern Med. 2015; 175(4): 578–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diao D, Wright JM, Cundiff DK, Gueyffier F. Pharmacotherapy for mild hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012; (8): CD006742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheppard JP, Stevens S, Stevens R, et al. Benefits and harms of anti-hypertensive treatment in low-risk patients with mild hypertension. JAMA Intern Med. 2018; 178(12): 1626–1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Viera AJ, Hawes EM. Management of mild hypertension in adults. BMJ. 2016; 355: i5719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimbo D, Abdalla M, Falzon L, Townsend RR, Muntner P. Role of ambulatory and home blood pressure monitoring in clinical practice: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. 2015; 163(9): 691–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agarwal R. Implications of blood pressure measurement technique for implementation of Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT). J Am Heart Assoc. 2017; 6(2): e004536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McManus RJ, Mant J, Franssen M, et al. TASMINH4 investigators Efficacy of self-monitored blood pressure, with or without telemonitoring, for titration of antihypertensive medication (TASMINH4): an unmasked randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018; 391(10124): 949–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giugliano D, Esposito K. Clinical inertia as a clinical safeguard. JAMA. 2011; 305(15): 1591–1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saver BG, Martin SA, Adler RN, et al. Care that matters: quality measurement and health care. PLoS Med. 2015; 12(11): e1001902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karmali KN, Lloyd-Jones DM, van der Leeuw J, et al. Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration Blood pressure-lowering treatment strategies based on cardiovascular risk versus blood pressure: a meta-analysis of individual participant data. PLoS Med. 2018; 15(3): e1002538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carter BU, Kaylor MB. The use of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring to confirm a diagnosis of high blood pressure by primary-care physicians in Oregon. Blood Press Monit. 2016; 21(2): 95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kent ST, Shimbo D, Huang L, et al. Rates, amounts, and determinants of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring claim reimbursements among Medicare beneficiaries. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2014; 8(12): 898–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shimbo D, Kent ST, Diaz KM, et al. The use of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring among Medicare beneficiaries in 2007-2010. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2014; 8(12): 891–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Babbott S, Manwell LB, Brown R, et al. Electronic medical records and physician stress in primary care: results from the MEMO Study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014; 21(e1): e100–e106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Østbye T, Yarnall KS, Krause KM, Pollak KI, Gradison M, Michener JL. Is there time for management of patients with chronic diseases in primary care? Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(3):209–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arrieta A, Woods JR, Qiao N, Jay SJ. Cost-benefit analysis of home blood pressure monitoring in hypertension diagnosis and treatment: an insurer perspective. Hypertension. 2014; 64(4): 891–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pickering TG, Miller NH, Ogedegbe G, Krakoff LR, Artinian NT, et al. American Heart Association; American Society of Hypertension; Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association Call to action on use and reimbursement for home blood pressure monitoring: a joint scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American Society of Hypertension, and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008; 23(4): 299–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jackson SL, Ayala C, Tong X, Wall HK. Clinical implementation of self-measured blood pressure monitoring, 2015-2016. Am J Prev Med. 2019; 56(1): e13–e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Booth JN, III, Muntner P, Diaz KM, et al. Evaluation of criteria to detect masked hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016; 18(11): 1086–1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Viera AJ, Lin FC, Tuttle LA, et al. Levels of office blood pressure and their operating characteristics for detecting masked hypertension based on ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Am J Hypertens. 2015; 28(1): 42–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anstey DE, Pugliese D, Abdalla M, Bello NA, Givens R, Shimbo D. An update on masked hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2017; 19(12): 94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fedorowski A, Stavenow L, Hedblad B, Berglund G, Nilsson PM, Melander O. Orthostatic hypotension predicts all-cause mortality and coronary events in middle-aged individuals (The Malmo Preventive Project). Eur Heart J. 2010; 31(1): 85–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rose KM, Eigenbrodt ML, Biga RL, et al. Orthostatic hypotension predicts mortality in middle-aged adults: the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC) Study. Circulation. 2006; 114(7): 630–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khera R, Valero-Elizondo J, Okunrintemi V, et al. Association of out-of-pocket annual health expenditures with financial hardship in low-income adults with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the United States. JAMA Cardiol. 2018; 3(8): 729–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.