Reports have been published from multiple countries regarding increased thrombus formation in COVID-19 patients, especially critically ill patients. These include DVT formation as well as pulmonary embolism and stroke. Currently, the exact mechanism as to why COVID-19 patients are at higher risk for thrombotic complications has not been determined. It has been thought to be due to endothelial injury, blood stasis or a hypercoagulable state [1]. To our knowledge this is the first reported case of phlegmasia cerulea dolens in a patient diagnosed with COVID-19.

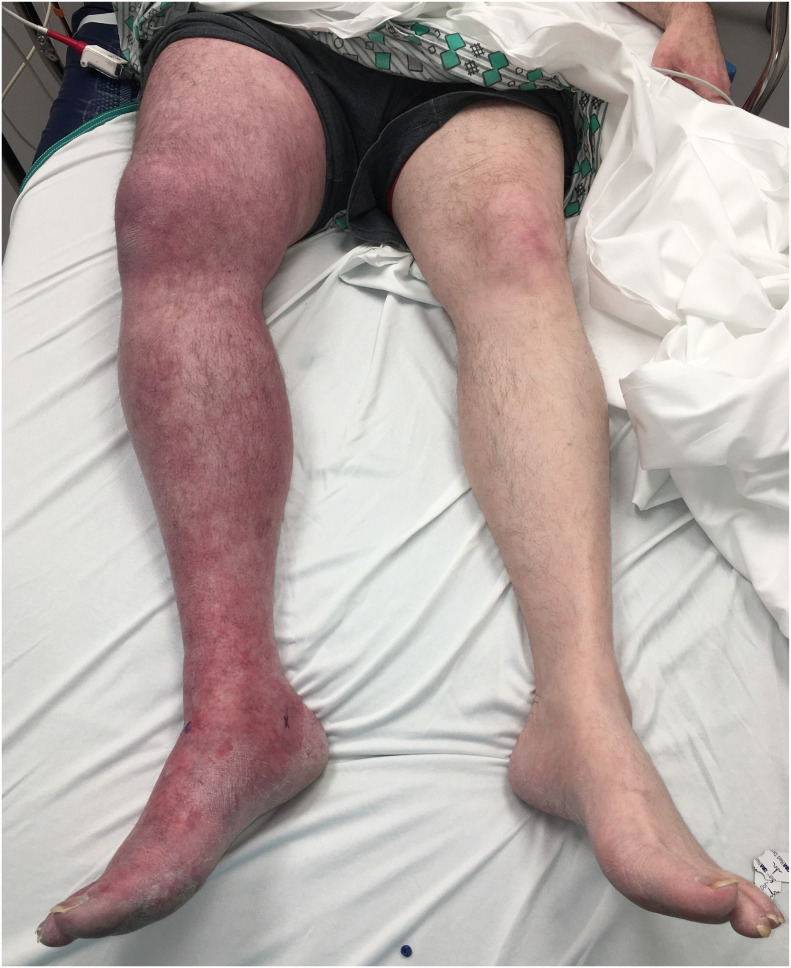

A 55-year-old male presented to the emergency department (ED) with sudden onset of right leg pain, swelling and discoloration. He reported a fever and dry cough which began three weeks prior. He stated his symptoms had resolved and he returned to work one day prior to his ED visit. His past medical history was significant for a motor vehicle collision 9 years prior that required multiple surgeries and as a result he developed a DVT and had an IVC filter placed. He had no other significant medical history and did not take any medications. Vitals signs in the ED were: temperature 36.8 °C, heart rate 85 bpm, blood pressure 107/59 mm/Hg, respirations 18, pulse oximetry 100% on room air. Physical exam revealed the right lower extremity to be purple and diffusely swollen from the groin to the toes and tender (Fig. 1 ). Pulses were not palpable; however, they were detected via Doppler. His calf was firm, his range of motion was limited due to pain and his capillary refill was delayed. The remainder of his physical examination was unremarkable.

Fig. 1.

Patient's legs at time of presentation to the emergency department.

Ultrasound revealed occlusive thrombus beginning in the right external iliac through the common femoral, femoral and popliteal veins and into the calf. Chest x-ray revealed bilateral patchy infiltrates. CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis demonstrated a subsegmental pulmonary embolism in the medial right middle lobe, thrombus within the distal IVC, right common and external iliac vein, and a possible thrombosed right proximal gonadal vein. He was started on heparin in the ED and vascular surgery and the medical intensive care unit (ICU) were consulted. The decision was made to give 50 mg of intravenous alteplase. Labs revealed elevations of: D-dimer 17,300 ng/mL, c-reactive protein 4.8 mg/dL, high-sensitivity troponin-T 23 ng/dL, basic natriuretic peptide 612 pg/mL, ferritin 813.8 ng/mL, fibrinogen 106 mg/dL, lactic acid 5.8 mEq/L, and IL-6 19 pg/mL. Rapid COVID-19 was positive, and PT/PTT/INR were normal. The patient was admitted to the ICU for further management. He was continued on heparin and transitioned to oral anticoagulation and discharged home on hospital day 7.

Coagulopathy has been studied in both the critically ill, ICU and non-ICU COVID-19 patients. Thrombotic complications include deep venous thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE), ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, and systemic arterial embolism. Critically ill ICU patients had a 31% increase in these complications when compared to non-ICU patients in a study from the Netherlands and France [2]. Another study compared non-ICU COVID-19 patients to other hospitalized patients and found an increased prevalence in DVT in the COVID-19 patient population [3]. They also found that 53% of patients with COVID-19 had DVT compared to 20% of bed-ridden, non-COVID-19 patients.

Cytokine storm has been implicated in COVID-19 and associated with severe infection [4], allowing for a focus on cytokine and other proinflammatory markers. It is suspected that the extensive release of cytokines causing a proinflammatory state may play a role in thrombus formation [5]. Tanaka et al. reported that IL-6 could activate the coagulation cascade [6], increasing the risk of thrombosis and complication. Our patient did have an elevated level of IL-6, in addition to hypertension and elevated CRP, which are all independent risk factors for increased severity of COVID-19 infection [7].

Helms et al. found that 50 of 57 patients had positive lupus anticoagulant and antiphospholipid (aPL) antibodies [1], both of which have been associated with thrombotic complications. Our patient was later found to have an elevated cardiolipin IgM, which could have theoretically contributed to his thrombosis. Other viral infections have been associated with aPL antibodies and thrombotic complications [8]. Zhang et al. found three patient cases with positive aPL antibodies who were found to have cerebral infarctions in COVID-19 [9]. One patient of interest in their report also had evidence of ischemia in the lower extremities. Although it cannot be determined if patients had positive aPL antibodies prior to COVID-19 infection, it is known that aPL antibodies have demonstrated pro-thrombotic complications in patients [8].

While not all patients diagnosed with COVID-19 develop thrombotic complications, it is important for emergency physicians to consider COVID-19 as the cause of a patient's hypercoagulable state even if symptoms have improved. The use of anticoagulants for thrombus prophylaxis in patients with COVID-19 infections is an area under investigation. The use of inflammatory markers and other laboratory values can also be utilized as an indication of a patient's clinical course as they progress through treatment.

Prior presentations

None.

Funding sources/disclosures

None.

Author contribution statement

MHM conceived and designed the study. MHM and CLL contributed to the medical management of the patient in the emergency department. MHM drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed substantially to its revision. MHM takes responsibility for the paper as a whole.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

References

- 1.Helms J. High risk of thrombosis in patients in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06062-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klok et al Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19 F.A. Klok, et al., Thromb Res 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Marone E.M., Rinaldi L.F. Upsurge of deep venous thrombosis in patients affected by COVID-19: preliminary data and possible explanations [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 17] J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2020.04.004. S2213-333X(20)30214-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu J., Li S., Liu J. Longitudinal characteristics of lymphocyte responses and cytokine profiles in the peripheral blood of SARS-CoV-2 infected patients [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 18] EBioMedicine. 2020:102763. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China [published correction appears in Lancet. 2020 Jan 30] Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanaka T., Narazaki M., Kishimoto T. Immunotherapeutic implications of IL-6 blockade for cytokine storm. Immunotherapy. 2016;8(8):959–970. doi: 10.2217/imt-2016-0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu Z., Cai T., Fan L. Clinical value of immune-inflammatory parameters to assess the severity of coronavirus disease 2019. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;95:332–339. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.04.041. [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 22] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uthman Imad W., Gharavi Azzudin E. Viral infections and antiphospholipid antibodies. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2002;31(4):256–263. doi: 10.1053/sarh.2002.28303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y., Xiao M., Zhang S. Coagulopathy and antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(17):e38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2007575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]