Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has created unprecedented disruption in health care delivery around the world. In an effort to prevent hospital-acquired COVID-19 infections, most hospitals have severely curtailed elective surgery, performing only surgeries if the patient’s survival or permanent function would be compromised by a delay in surgery. As hospitals emerge from the pandemic, it will be necessary to progressively increase surgical activity at a time when hospitals continue to care for COVID-19 patients. In an attempt to mitigate the risk of nosocomial infection, we have created a patient care pathway designed to minimize risk of exposure of patients coming into the hospital for scheduled procedures. The COVID-minimal surgery pathway is a predetermined patient flow, which dictates the locations, personnel, and materials that come in contact with our cancer surgery population, designed to minimize risk for virus transmission. We outline the approach that allowed a large academic medical center to create a COVID-minimal cancer surgery pathway within 7 days of initiating discussions. Although the pathway represents a combination of recommended practices, there are no data to support its efficacy. We share the pathway concept and our experience so that others wishing to similarly align staff and resources toward the protection of patients may have an easier time navigating the process.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has led to the rapid restructuring of hospitals and hospital operations around the urgent need to care for large numbers of critically ill patients while protecting patients and staff. To this end, elective surgeries have largely been cancelled at hospitals in countries and regions affected by the pandemic in order to preserve resources needed to care for patients with COVID-19 and to minimize patient exposure. However, many hospitals continue to perform surgeries in patients whose survival or permanent function could be compromised by delaying surgery (ie, “urgent operations”). Included among these urgent surgical procedures are a range of procedures for cancer treatment. Many patients requiring cancer operations are elderly and have medical problems, making a COVID-19 infection potentially more dangerous.1 , 2 As a result, hospitals must take additional precautions to minimize the risk of COVID-19 infection among these particularly vulnerable patient populations.

The precise risk of acquiring a COVID-19 infection during an episode of hospital care is unknown. Risk for nosocomial infection likely parallels general principles of COVID-19 transmission, which are related to proximity and duration of contact with COVID-19–infected individuals, as well as contact with materials harboring the virus.3 Early data from Europe and Asia have confirmed that nosocomial infections occur in patients coming to hospitals from home for cancer surgery.4 , 5 When patients with cancer do become infected by COVID-19, they are at higher risk than the general population for adverse effects, such as intensive care unit admission, intubation, and death.6 While it is unlikely that hospitals can completely eliminate the potential for viral transmission from infected patients, there are several approaches capable of mitigating risk (eg, wearing of masks, hand washing, distancing). As the proportion of COVID-19 patients increases within a hospital census, the potential for inadvertent contact with people and materials capable of transmitting the virus also increases, requiring a deliberate plan to protect the cancer surgery population. Similarly, as hospitals begin to recover from the pandemic and relax triage restrictions, there will be a need to increase surgical activity at a time when COVID-19 patients constitute a significant proportion of hospital census.

Our interdisciplinary team created a COVID-minimal cancer surgery pathway to minimize the risk of nosocomial COVID-19 infection among patients coming from home for cancer surgery. The pathway is a combination of current best practices in COVID-19 transmission prevention,7 and a defined flow of patients throughout their hospitalization. From the parking garage to the patient’s discharge, specific patient locations and transportation routes were designed to minimize contact with people and materials thought to carry the highest risk of transmitting COVID-19 infection. The pathway integrates best practice recommendations, and the shared experiences from some of the most severely affected regions of Europe, Asia, and North America. The pathway is not proposed as the optimal approach to performing surgery during the pandemic. Rather, the pathway is described to facilitate its replication by surgical teams who share our opinion regarding the value of isolating the cancer surgery population, to the extent it is possible, through their hospital course during the pandemic.

COVID-Minimal Pathway as a Concept

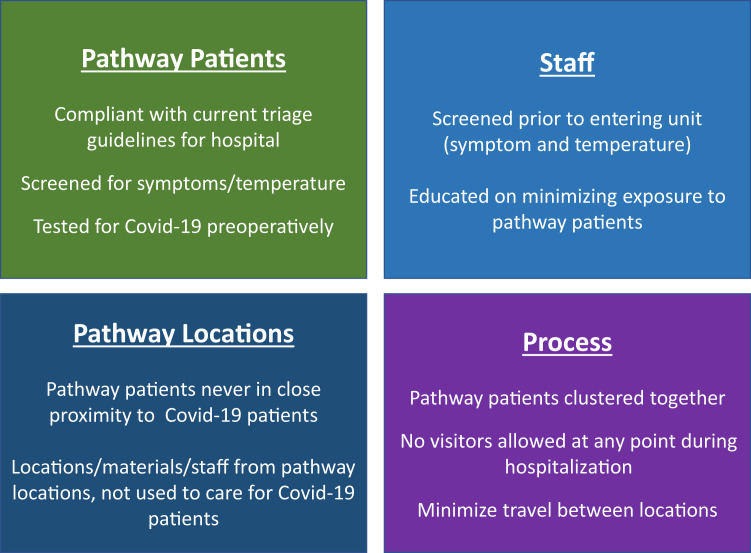

The COVID-minimal pathway is simply a set of predetermined steps that define a patient’s flow through the hospital as they prepare for, undergo, and recover from surgery. The key components of the pathway relate to the locations in which care takes place, patient selection, staff screening, and the process by which care is delivered (Figure 1 ). The pathway is designed to minimize contact of surgery patients with people, space, and materials that are also in contact with (1) COVID-19–positive patients, (2) COVID-19–suspected patients, or (3) COVID-19–status unknown patients.

Figure 1.

Key components to the COVID-minimal pathway. (COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.)

Realities of the COVID-19 Era

The COVID-19 pandemic is a global problem that is locally managed. Every hospital is uniquely affected resulting in varying proportions of space, staff, and supplies being committed to the pandemic. Therefore, the COVID-minimal pathway would likely differ at each hospital, representing the patient flow that minimizes contact with people and materials most likely to transmit the virus, given the competing needs and available capacity. Another critical reality is that environments change rapidly, and space and personnel that could be available last week could be needed in the care of COVID patients the following week. Therefore, the pathway not only is likely to differ from hospital to hospital, but also may potentially differ from week to week.

Key Steps to Creating Pathway

In order to establish a COVID-minimal surgical pathway, there are a number of steps that should be followed to ensure not only proper communication, but also feasibility, and to minimize wasted or duplicative effort. For most hospitals and health systems, the leadership is already over-extended managing the capacity and care for the COVID-19 population. Therefore, every effort should be made to have a “grassroots” approach, in which problems are presented with alternative solutions, or else this may overload the ability of leadership to process. The pathway should be designed with the direct engagement of unit-level managers and their frontline staff members, as these interdisciplinary teams will be best equipped to design and integrate COVID-minimal surgical pathways in a time-sensitive fashion.

Confirm Interest and Support From Surgical, Perioperative, and Inpatient Leaders

Before investing time into a pathway, it is critical to establish a critical mass of surgeon leaders willing to commit to using the COVID-minimal pathway. The surgeon support does not have to be unanimous or to encompass all types of surgical operations. However, surgeons that share resources and infrastructure should be aligned in their participation (eg, Division of Thoracic Surgery, urology surgeons). Ultimately, there must be a commitment of a critical mass of interested users to justify the effort. Similarly, support from the leaders of perioperative services and the inpatient care team leaders is needed, as coordinating care in these areas is critical to having a pathway.

Identify Leadership Team

The creation of a novel care pathway requires a multitude of decisions to be made affecting locations within and outside of the pathway. In addition to overall support from surgical services, perioperative services, and inpatient services, engagement at multiple levels from these teams is needed. This will facilitate not only key approvals, but also the overall effort benefits from critical insight from different stakeholders that will streamline the desired changes and minimize the fallout from potential oversights. A list of key stakeholders representing related components of the pathway at our institution is outlined in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Key Stakeholders

| Role | Perspective and Mission |

|---|---|

| Bed management | Direct the flow of patients into the space allocated to the pathway |

Nurse managers

|

|

Administration

|

|

Pathology

|

|

| Radiology |

|

OR scheduling

|

|

Training program supervisor

|

|

OR, operating room; PACU, postoperative care unit; SICU, surgical intensive care unit.

Establish Consensus Definition of “COVID-Minimal”

At each step of the pathway, there are multiple iterations of patient flow and process that could potentially reduce exposure to COVID-19–infected people or materials. Given that much of a hospital’s space and resources are likely committed to the care for growing COVID-19 patient populations, there are limits to the steps that can be taken to isolate the cancer surgery pathway patients from individuals, space, and materials that are outside the pathway. Therefore, in each location, at each point in time (because conditions may change quickly), leadership must determine extent to which pathway patients can be isolated, given their competing needs in caring for patients outside the pathway. Establishing consensus targets is helpful. For example, our goal at pathway inception was to minimize contact between pathway patients and space, people, and materials that were also in contact with COVID-19–positive patients, suspected COVID-19 patients, or COVID-19–unknown patients. This was not universally feasible, but in each location, our interdisciplinary team was able to define a consensus target.

Define and Prepare Space

A cornerstone to the pathway’s intended function is minimize contact between patients on the pathway with people, materials, and space that are in contact with COVID-19 patients. From the parking garage to the admitting area, preoperative area, operating rooms, recovery rooms, and patient floors, efforts should be made to isolate the pathway patients (Figure 2 ). In some settings, it may be possible to use separate campuses and buildings that are used exclusively for cancer surgery pathway patients (this is rare). More commonly, there may be opportunities to commit specific units, or portions of units to be designated for the pathway in which cancer surgery patients are spaced apart from COVID-19 patients. For example, specific operating rooms could be designated for the exclusive use by pathway patients. In addition to be not allowing COVID-19, suspected COVID-19, or COVID-19–unknown patients to have surgery in these rooms, ideally, the COVID-minimal pathway rooms would be geographically separated from those dedicated to the care of COVID-19 patients. In this way not only are personnel and equipment less likely to cross between rooms, but also during transportation it would be less likely that patients would pass through potentially infected spaces. At a minimum, specific portions of shared units should be reserved for pathway patients that are free of known or suspected COVID-19 patients. Barriers when feasible should be employed for patients who could in their normal activities come within 6 feet of one other (eg, because of bed spacing). Wherever possible, equipment should not be shared between COVID-19 patients and pathway patients, or a specific decontamination protocol should be employed. Clustering patients together in locations on the pathway provides logistical and practical advantages, as they could serve as lower-risk neighbors to each other on the patient floors.

Figure 2.

Example of COVID-minimal (C-M) patient flow diagram. Within each location, there is dedicated space for the patients on the COVID-minimal pathway that is separated to the best extent possible from known or suspected coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients.

For situations in which the COVID-minimal pathway involves a separate hospital, building, or campus, several additional adjustments may be required. Teams from the normal floor, operating room, and intensive care unit must be engaged to share patient protocols and location of equipment and materials. The team members (physicians, nurses, physician assistants, residents) will need access with their identification tags and may need parking and locker space.

Define Routes of Travel Between Locations on Pathway

Efforts should be made to limit the travel distance between care locations on the pathway. Where it is possible, the pathway should avoid the hallways, corridors, and elevators used by medical teams and patients with known or suspected COVID-19 infections. Efforts should be made to remove unnecessary materials and equipment from the pathway to improve passage and facilitate cleaning. Visible signage should be placed on walls and floors to remind staff of the importance of confined routes of travel.

Communicate to Staff and Patients the Purpose and Details of the Pathway

Once a pathway is in place, full implementation will require patients and caregivers to know the steps of the pathway. Compliance with the pathway will likely be enhanced by having patients and staff be fully informed as to the rationale and purpose of the pathway. It is also likely that staff and patient engagement will identify additional opportunities to minimize risk of hospital-acquired COVID-19 transmission.

Patient Screening

Before coming into the hospital, steps should be taken to minimize the possibility that the patient already is infected with COVID-19. The person should be advised at the time of scheduling that they should note any symptoms that could represent a COVID-19 infection and check their temperatures. In locations where sufficient testing is available, patients should be tested for COVID-19 within the 24 hours leading up to surgery. Ideally, this would take place in a location that is closer to the patient’s home and allow for patients to check the results before driving to the hospital in the morning. Once the patient arrives for surgery, they should be screened for symptoms and have their temperature taken before entering the pathway. Once in the pathway, the patients should be advised to partake in frequent handwashing, of the need for distancing, and of potentially wearing a mask where one is available.

Staff Screening

Staff should be educated on symptoms to note and should check their temperatures before coming to work, and not report for duty if febrile. Upon arrival, staff should be screened for symptoms and have their temperature checked and recorded. In our organization, we have elected to log staff temperatures with paper records that are maintained by the unit manager. Staff should wear masks if sufficient supplies are available, as well as practice distancing where appropriate and hand hygiene (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention best practices).

Restriction of Visitors

Visitors are restricted from the COVID-minimal surgical pathway, to minimize exposure of patients and staff from individuals who are not critical to the patient’s care and could potentially harbor a COVID-19 infection. Patients who are brought to the hospital by someone else must say goodbye as the patient is checked into admitting. This must be communicated early in the process so that patients and the individuals who support them can be prepared for this restriction. There may be exceptions for pediatric patients.

Pathway Facilitators

Several initiatives may enhance the implementation and adoption of the pathway steps, by increasing communication, or adding clarity:

-

-

A webpage containing key information for patients and visitors, informing them of the changes and why changes are being made, as well as of the instructions for preoperative testing (taking temperature at home, going for COVID-19 testing preoperatively)

-

-

Signage to indicate the flow through the pathway, so that patients and transport staff adhere to routes

-

-

Indicator in electronic medical record: a note that let allows everyone to recognize that the patient has been designated for the pathway, so that they can be routed appropriately

Triage Meetings

In order for the pathway to meet the needs of the multiple service lines, it is important to coordinate the resources with surgical volumes. Each week, it is critical to discuss the clinical activity for the following week to ensure that (1) planned surgeries are consistent with current triage guidance, (2) there are sufficient resources for the patient (eg, operating room access, floor access, resident coverage), and (3) that the workload is optimally distributed across the surgical services participating in the pathway. An example of a table to document activity and assurances from resource managers is given as Table 2 .

Table 2.

COVID-Minimal Cancer Surgery Pathway

| Weekly Case Triage Conference Week Starting: |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Sat | |

| Number of Cases | ||||||

| ENT | ||||||

| Thoracic | ||||||

| Surgical oncology | ||||||

| Colorectal | ||||||

| Gynecology oncology | ||||||

| Endocrine | ||||||

| Breast | ||||||

| Robot neededa | ||||||

| Sign-Offsb | ||||||

| Division chief case review | ||||||

| SICU need | ||||||

| PACU issues | ||||||

| Anesthesia issues | ||||||

| OR | ||||||

| Floor beds needed | ||||||

| Resident coverage | ||||||

| Other | ||||||

COVID, coronavirus disease; ENT, ear, nose, and throat surgery; OR, operating room; PACU, postoperative care unit; Sat, Saturday; SICU, surgical intensive care unit.

If robot access is limited, then service utilization will have to be coordinated;

Leaders from each area will confirm that resources, space, and personnel are available and clinical activity is appropriate given triage status.

Strategy Meetings

On a weekly basis, it is important to review the results of pathway in terms of (1) compliance with pathway, (2) access for cases eligible for pathway, (3) utilization of pathway, (4) COVID-19 infections among patients on the pathway, and (5) needed changes. The leadership team should participate in this call.

Key Considerations

There are several potential issues to consider at the pathway’s inception. First and foremost is the reaction should a patient on the pathway develop symptoms of COVID-19 infection. If a patient is found to be COVID-19–positive during the preoperative test, then a plan should be made for monitoring the patient’s status, as well as for a strategy to reevaluate the patient for surgery (repeating the test at some point after symptoms have resolved). If the patient has already undergone surgery and develops symptoms while recovering from surgery in the hospital, there must be a way to relocate the patient from the pathway. If the planned pathway locations become overpopulated, there should be a plan for overflow, or a mechanism to defer surgeries until the following week.

Comment

The described pathway represents our attempt to minimize the risk of patient exposure to COVID-19 infection during a hospital stay for urgent cancer surgery. The COVID-minimal pathway will be important during the recovery phase, as triage restrictions are slowly relaxed, and surgical volumes increase, potentially at time when many COVID-19 patients are hospitalized. There are no data to support that implementation of the proposed pathway will reduce the risk of nosocomial COVID-19 infections. We have created the pathway to address, to the best that we were able, the modifiable factors that we interpret to harbor the greatest potential to transmit COVID-19 to patients coming from home for cancer surgery.

Without evidence to indicate the pathway eliminates the risk for nosocomial infections, we continue to include the risk of hospital-acquired COVID-19 infection as a critical component of our surgical consent process. Furthermore, we would not use this pathway as a justification to relax restrictions on the type of patient scenarios eligible for surgery (eg, elective surgeries). In the future, if data indicated that such a pathway could prevent nosocomial infection, it would be reasonable to incorporate the pathway into a regional effort to relax surgical case restrictions (if resources and beds allowed). Until such a time, we would support using the pathway for cases that are currently approved by hospital and governmental leadership.

There is no novel “intervention” contained within the pathway, other than an effort to create a hospital-wide awareness to protect this particularly vulnerable patient population. Perhaps the greatest agent of change may prove to be simply engaging individuals at each location care is delivered, communicating the purpose, and educating staff on the best practices.

The implementation strategy used is not novel. Our approach of securing buy-in, identifying key stakeholders, creating a process map, and embarking on campaign of staff education would be considered standard practice. Our pace was remarkable for our institution. Following the outlined approach, we were able to initiate care on the pathway within 7 days of initial discussions. Among participants of the leadership team, the consensus was that a similar effort could have easily taken several months at our institution. Our experience was greatly facilitated by forward thinking leadership, favorable geography (2 large hospital campuses within 2 miles of each other), experienced midlevel management, engagement of frontline staff, and a clear articulation of a pressing patient safety issue.

The pathway was designed for patients having surgery to treat a malignancy, having been identified as a particularly vulnerable population. However, the pathway could certainly be applied to other surgical populations (eg, cardiovascular surgery, neurosurgery). The pathway focuses on “inpatient” surgery (ie, patients coming from home but then are admitted). A similar pathway could be created for outpatient surgery, potentially involving smaller facilities that are not currently being used to treat known COVID-19–infected patients.

We claim no ownership of the pathway, which developed out of learnings from discussions with colleagues around the world, attended and hosted webinars, and our collective intuition. The pathway is not meant to be a static entity, but rather was designed to be modified as data emerge and conditions at our hospital change. We encourage readers to communicate widely any additional guidance or clarification, or challenge any of our assumptions, as our interest lies in the optimal outcomes of our patients, and any improvements would be welcomed.

We share this pathway not because we know it to be the best way forward. Rather, we are sharing the manner in which we have navigated our obstacles, in hopes that others may have a smoother journey.

Acknowledgments

Dr Ahuja has licensed methylation biomarkers to Cepheid and has received grant funding from Astex.

References

- 1.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Groups at higher risk for severe illness. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/groups-at-higher-risk.html Available at:

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention How COVID-19 spreads. April 13, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/how-covid-spreads.html Available at: [PubMed]

- 4.Lei S., Jiang F., Su W. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients undergoing surgeries during the incubation period of COVID-19 infection. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;21:100331. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu J., Ouyang W., Chua M.L.K. SARS-CoV-2 transmission in patients with cancer at a tertiary care hospital in Wuhan, China. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:1108–1110. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liang W., Guan W., Chen R. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335–337. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization Basic protective measures against the new coronavirus. https://www.who.int/southeastasia/outbreaks-and-emergencies/novel-coronavirus-2019/protective-measures Available at: