ABSTRACT

Vaccine hesitant parents are linked with re-emergence of vaccine preventable diseases, but evidence is scarce locally. The Parent Attitudes about Childhood Vaccines (PACV) questionnaire was validated and used in the USA to identify vaccine hesitant parents. This study aimed to adapt and translate the 15-item PACV questionnaire from English into the Malay language, and to examine its validity and reliability. The sample population was parents of children aged 0–24 months, recruited at an urban government health clinic between November 2016-June 2017. During content validation, two items from the “Behavior” subdomain were identified as items with formative scale and excluded from exploratory factor analysis (EFA) but retained as part of demography. A total of 151 parents completed the questionnaire with response rate of 93.3%. Test-retest reliability was tested in 25 respondents four weeks later and the intra-class correlation was between 0.53 and 1.00. EFA of the 13 items showed possibility of two to four factor domains, but three domains were most conceptually equivalent. Two of the domains were similar to the original and one factor was identified de novo. One item was deleted due to poor factor loading of < 0.3. Therefore, the validated final PACV-Malay consisted of 12 items framed within three-factor domains. The PACV-Malay was reliable with total Cronbach alpha of 0.77. In conclusion, the PACV-Malay is a valid and reliable tool which can be used to identify vaccine hesitant parents in Malaysia. Confirmatory factor analysis and predictive validity are recommended for future studies.

KEYWORDS: PACV, Malaysia, childhood vaccinations, immunizations, vaccine hesitancy, adaptation, translation, validation, questionnaire

Introduction

The implementation of immunization programs has successfully reduced the burden of communicable diseases globally.1,2 In Malaysia, the national immunization program, improved conditions of daily living such as water and sanitation, and specific public health interventions had contributed to the substantial reduction of mortality among children due to communicable diseases including vaccine preventable diseases in the past three decades.3,4 Despite its significant contribution to global health, there are growing concerns on safety of vaccines, increasing vaccine hesitancy among parents5 and the emergence of vaccine preventable diseases in recent years including in Malaysia.6-11

Vaccine hesitancy has been linked with the increased incidence of vaccine preventable diseases. It is defined as delayed in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite availability of vaccination services.12 Vaccine hesitant individuals are individuals who have varying degrees of indecision about specific vaccines or vaccination in general.12 Vaccine hesitant parents (VHPs) are important individuals to be identified early as their attitude toward vaccination may not be extreme, and there is a role of positive influence to increase immunization uptake among these individuals. However, there is paucity on data about vaccine hesitancy among parents in Malaysia.

The Parent Attitudes about Childhood Vaccines (PACV) questionnaire is a validated questionnaire which has a predictive ability to help identify VHPs and subsequently provide room for intervention.13-15 The validated questionnaire has 15 items within three subdomains “Safety and efficacy”; “General attitudes”; and “Behavior” with Cronbach alpha of 0.74, 0.84 and 0.74, respectively.15 A scoring validation study had shown that there was a statistically significant linear association between a parent’s total score on the 15-item PACV and their child’s immunization status.16

This questionnaire was validated in Washington, USA. To our knowledge, this tool has not been validated and psychometrically tested in the Malay language. Hence, we aimed to adapt and translate the original PACV questionnaire from the English language to Malay language and to subsequently examine its psychometric properties.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

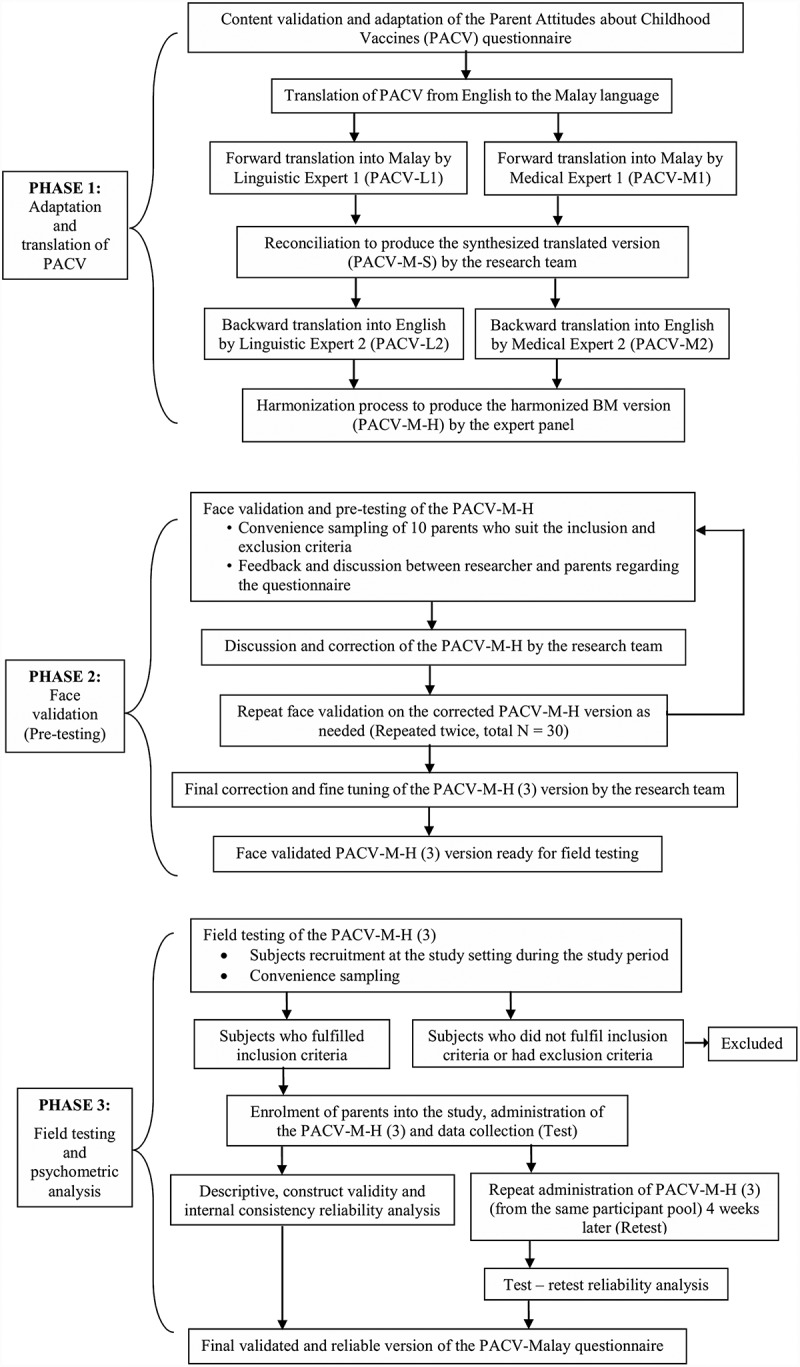

This was a cross-sectional questionnaire translation and validation study. It involved three phases i) adaptation, content validation and translation of the PACV questionnaire from English into the Malay language; ii) face validation of the PACV-Malay version (pre-testing); and iii) psychometric evaluation of the PACV-Malay version to assess its validity and reliability (including test-retest). The study was conducted between November 2016 and June 2017 at a public primary health-care clinic situated in an urban area. Figure 1 outlines the study process.

Figure 1.

Overview of the conduct of the study.

Phase 1: adaptation, content validation and translation

Phase 1 of the study involved adaptation process which included content validation by the expert panel. The expert panel was five consultants and experts in Primary Care Medicine, Public Health and Population Medicine, Pediatrics and questionnaire translation and validation research. The panel reviewed the original 15-item questionnaire and scrutinized each item for its content and relevance to the Malaysian population. The adapted questionnaire was then forward and back-translated by four independent translators according to guideline recommendations for cross-cultural adaptation and translation studies.17-19 The available translations were then harmonized and reviewed by the expert panel. Discrepancies between the different versions were discussed to ensure initial conceptual, item, and semantic equivalence. At the end of phase 1, a PACV Malay-harmonized (PACV-M-H) version was produced.

Phase 2: face validation

Face validation aimed to determine clarity, comprehensibility, readability and feasibility of using the questionnaire among the target population. It was conducted on 10 participants who fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria as outlined below. Respondents were asked to clarify in detail what they understood, and asked to think aloud in their own words if there were any problems with the items. Following each face validation, comments and corrections were made.

Phase 3: field testing and psychometric evaluation

In phase 3, field testing of the PACV-M-H was done on parents who fulfilled the same inclusion criteria. However, the participants during phase 2 were not re-selected for phase 3 of the study, hence participants for Phase 2 and Phase 3 were mutually exclusive. Data collected were then subjected to psychometric evaluation. Items with factor loading of >0.3 were considered.20

Test-retest

All participants with an appointment interval of 4 weeks were invited to do a retest. Twenty-five respondents who returned after this period were given the same PACV-M-H questionnaire to complete the test-retest.

Sample size

A target sample size for phase 3 was calculated using the Sample to Variable Ratio (SVR) of 10:1 with a minimum of 150 respondents needed.21-24 The possibility of incomplete questionnaires, unreturned questionnaires or withdrawal of consent in 10% of the respondents were considered, hence the sample size was increased to 165 participants.

Sampling method and sampling population

Convenience sampling method was adopted with the aim of recruiting a variety of study participants which included fathers and mothers of different ethnicities and age groups. Recruitment was done over a period of 4 weeks. The sampling frame was parents attending the Maternal and Child Health unit of a public primary health-care clinic situated in Klang Valley. Parents who were present at the waiting area were approached and invited to participate. The sample population was Malaysian parents with at least one child who is between 0 and 24 months old and the parent was at least 18 years of age. Parents who were not able to read and understand the Malay language and parents who had cognitive impairment or intellectual disability were excluded from the study. All participants were provided with patient information sheet and gave written informed consent. The self-administered PACV-M-H questionnaire were completed by the participants while waiting for their turn in clinic. The participants were not rushed to answer the questionnaire to help reflect their true opinions. Demographic data were also collected. Upon completion, the questionnaire was returned to the researcher who then checked for completeness.

Research tool

The PACV is a 15-items questionnaire with three factor domains – “Behavior”, “Safety and efficacy”, and “General attitudes”. The original questionnaire consisted of 17 questions, of which the first two questions were regarding relationship to child and whether the child considered for the study was the firstborn. The 15 items of the questionnaire are the subsequent questions (Q3-Q17) (refer Appendix 1). Each item’s responses are grouped into hesitant responses which scored 2, unsure responses which scored 1 and non-hesitant responses which scored 0. However, for respondents who answered “Don’t know” for items 3 and 4 (Q3 and Q4) the mark will be dismissed. Hence, the total score range would be from a minimum of 0 to a maximum of either 30, 28 (if answered one “Don’t know” for Q3 or Q4) or 26 (if answered “Don’t know” for both Q3 and Q4). The total scores are then converted to a 0–100 scale. Based on previous validation studies, respondents who scored < 50 can be considered as non-hesitant parents, while those who scored ≥ 50 may be considered as vaccine hesitant parents.16

Statistical analysis

Data entry and statistical analysis were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 23.0. The data entered were checked for outliers and missing values. A scale of 1–5 were used to code respondent’s answers. The scale was converted from the questionnaire to denote an ordinal ranking, whereby a scale of 1 is a non-hesitant response, 3 is unsure while 5 is a hesitant response. Negative items were reverse coded to reflect the same response. Two items with 11-point Likert-scale were collapsed to the 1–5 scale. Descriptive statistics were used to illustrate the demographic data of the participants, responses to the items in the questionnaire and parents’ scoring. Floor and ceiling effects were noted. Sampling adequacy was assessed using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure value and appropriateness of data was conducted using the Bartlett’s test of sphericity. A KMO value of at least 0.5025 and a significant Bartlett’s test of sphericity with a p-value of <0.0526 would mean suitability to proceed to factor analysis. For psychometric properties of the questionnaire, construct validity was examined to review the dimensionality or structural validity by exploratory factor analysis (EFA). EFA using principal factor analysis with Promax rotation (Eigenvalue ≥ 1) was used. Only items with factor loading of >0.3 were considered. Hypothesis testing was also considered. Criterion validity was not examined in this study as it was not applicable.

Reliability was measured by internal consistency analysis and Cronbach alpha. To represent high internal consistencies, Cronbach alpha of 0.50–0.70 were considered as reliable.27,28 Test-retest data were assessed by calculating the intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC). It is calculated as the ratio of the sums of variance component estimates and defined to be within the interval of 0 to 1, with <0.40 considered poor, between 0.40 and 0.59 considered fair, 0.60–0.74 is good and ≥0.75 is excellent.29

Ethical consideration

We obtained written permission from the instrument developer Douglas J. Opel, University of Washington, Seattle to adapt, translate and validate the PACV. The Ethics Committee of the Research Management Institute (RMI) of Universiti Teknologi MARA (UITM) (REC/90/15) and the Medical Research and Ethics Committee from the Ministry of Health Malaysia approved the study protocol. It is in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975.

Results

The adaptation, content validation, translation and face validation of PACV-Malay

The expert panel concurred that all 15 items were considered appropriate for the Malaysian population. Two items (Q3, Q4) with a formative answer scale (“Yes”, “No” and “Don’t know”) were excluded from psychometric analysis. These items enquired the child’s immunization history (Q3 – “Have you ever delayed having your child get a shot for reasons other than illness or allergy?” and Q4 – “Have you ever decided not to have your child get a shot for reasons other than illness or allergy?”) rather than a hesitant behavior. However, they were retained in the PACV-Malay questionnaire as part of demography questions as they are deemed important to highlight VHPs.

During forward translation, there was a difference of opinion pertaining to item Q6 (“Children get more shots than are good for them”). Following back translation and final harmonization process, the most suitable translation was chosen. We referred back to the development of the original PACV questionnaire,14 and noted that Q6 and Q9 (“It is better for children to get fewer vaccines at the same time”) were derived from a different statement to improve the validity of PACV. Hence, as these two items were related in score prediction, Q9 was also reviewed to ensure correct conceptualization. Finally, the harmonized translated questionnaire, the PACV-M-H version was produced and ready for face validation.

During the first face validation, all respondents found the questionnaire was clear and easy to understand. There were discrepancies for Q6 and Q9 responses, which ideally should be concordant. The items were revised and the second version of the study tool, PACV-M-H (2) included three options for item Q6. Face validation was repeated. There were similar number of respondents who chose between the three options without any preference. The respondents were asked to think aloud about what they understood. The points were discussed again with the expert panel and PACV-M-H (3) was produced. The face validation process was repeated until there were no significant misunderstandings during the third face validation. Hence, a total of 30 respondents had participated in the face validation phase. The PACV-M-H (3) was then ready for field testing.

Field testing and psychometric evaluation

A total of 165 parents were approached but 11 (6.7%) refused to participate, with a response rate of 93.3%. In total, 151 completed questionnaires were analyzed. Majority were Malays (88.7%) and Muslims (89.4%). The mean age was 30.45 ± 4.26 years. The demographic characteristics of respondents are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of respondents (parents).

| Study sample N = 151 |

Percentage (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | 18 – 29 years | 64 | 42.4 |

| ≥ 30 years | 87 | 57.6 | |

| Relationship to child |

Mother | 133 | 88.1 |

| Father | 18 | 11.9 | |

| Others | 0 | 0 | |

| Firstborn child | Yes | 84 | 55.6 |

| No | 67 | 44.4 | |

| Number of children | One | 74 | 49.0 |

| Two | 36 | 23.8 | |

| Three | 30 | 19.9 | |

| Four or more | 11 | 7.3 | |

| Ethnicity | Malay | 134 | 88.7 |

| Chinese | 5 | 3.3 | |

| Indian | 9 | 6.0 | |

| Others | 3 | 2.0 | |

| Religion | Islam | 135 | 89.4 |

| Christian | 2 | 1.3 | |

| Buddha | 5 | 3.3 | |

| Hindu | 9 | 6.0 | |

| Others | 0 | 0 | |

| Personal status | Single | 3 | 2.0 |

| Married | 147 | 97.4 | |

| Living with a partner | 0 | 0 | |

| Widowed | 0 | 0 | |

| Separated | 0 | 0 | |

| Divorced | 1 | 0.7 | |

| Highest formal education | No formal education | 0 | 0 |

| Primary School | 2 | 1.3 | |

| Secondary School | 36 | 23.8 | |

| Certificate/Diploma/STPM | 54 | 35.8 | |

| Degree | 58 | 38.4 | |

| Postgraduate | 1 | 0.7 | |

| Household income (per month) |

≤ RM 580 | 0 | 0 |

| RM 581 – RM 940 | 4 | 2.6 | |

| RM 941 – RM 3000 | 57 | 37.7 | |

| RM 3001 – RM 10,000 | 78 | 51.7 | |

| ≥ RM 10,001 | 10 | 6.6 | |

| Vaccination record | Up to age | 117 | 77.5 |

| Missed vaccinations | 0 | 0 | |

| Missing data | 34 | 22.5 |

Responses to items

In the “General attitudes” domain, four items (Q7, Q14, Q15 and Q16) were noted to have floor effects (percent of respondents answering “strongly agree” exceeded 15%) and one item Q8 with ceiling effect (percent of respondents answering “strongly disagree” exceeded 15%) (Refer Appendix 2). There were no floor or ceiling effects for the “Safety” domain.

Validity analysis

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value was 0.736 with a significant p-value of <0.001 for the Bartlett’s test of sphericity. These results showed that the data set was suitable to proceed with further factor analysis. Thirteen items (Q5-Q17) in the PACV-M-H (3) underwent exploratory factor analysis (EFA). The 13 items had inter-item correlation between 0.30 and 0.70, of which one item (Q7) had borderline value of 0.295.

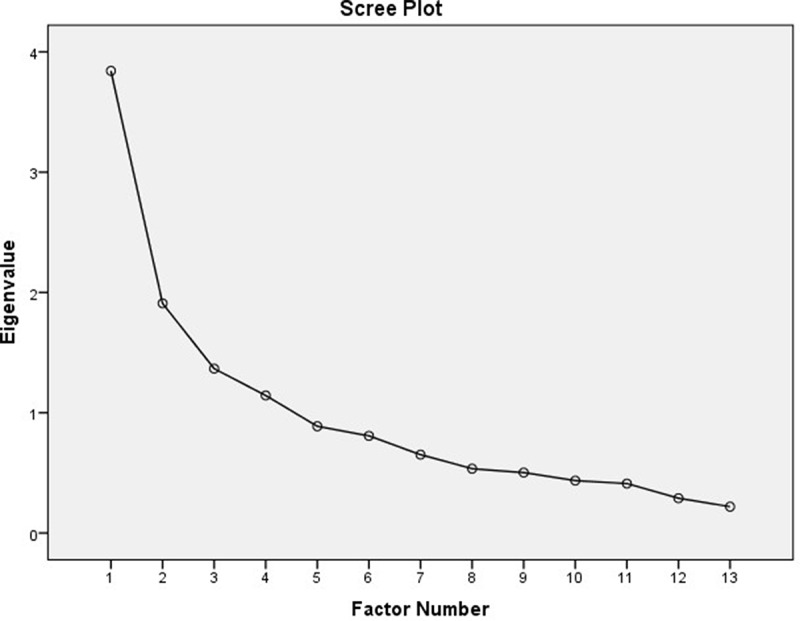

The Kaiser’s criterion showed four factors with Eigenvalues of ≥1, with the total variance of 63.55%. On the Scree plot, the elbow of the curve occurred at 2 (Figure 2). Using principle axis factoring with Promax rotation, four-factor domains were identified.

Figure 2.

Scree plot of the PACV-M-H (3).

Repeated component matrix analysis were done with factors fixed at two and three, and the three-factor solution was deemed to be the most conceptually appropriate and equivalent to the PACV questionnaire. Based on the analysis with factor fixed at three, it was noted that one item (Q7) did not load on any of the factors and deleted.

From the EFA, items in Factor 1 (Q5, Q13-Q17) correlate most closely to the “General attitudes” domain factor from the original questionnaire while items in Factor 2 (Q10-Q12) correlate most closely to the “Safety and efficacy” domain factor from the original questionnaire. The items in Factor 3 (Q6, Q8, Q9) correlated together to form a new domain de novo. These items were noted to reflect parents’ concerns regarding the amount and timing of childhood vaccinations. Reference was made to the theoretical framework model of determinants of vaccine hesitancy5 and thus Factor 3 was labeled as “Schedule and immunity”. The final items, domains, factor loadings and labeling are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Items, factor loadings, domains and labeling of the PACV-M-H (3).

| Coding | Items | Factor 1 |

Factor 2 |

Factor 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General attitudes | Safety and efficacy | Schedule and immunity | ||

| Q5 | How sure are you that following the recommended shot schedule is a good idea for your child? | 0.657 | ||

| Q13 | If you had another infant today, would you want him/her to get all the recommended shots? | 0.562 | ||

| Q14 | Overall, how hesitant about childhood shots would you consider yourself to be? | 0.499 | ||

| Q15 | I trust the information I receive about shots. | 0.531 | ||

| Q16 | I am able to openly discuss my concerns about shots with my child’s doctor. | 0.481 | ||

| Q17 | All things considered, how much do you trust your child’s doctor? | 0.835 | ||

| Q10 | How concerned are you that your child might have a serious side effect from a shot? | 0.733 | ||

| Q11 | How concerned are you that any one of the childhood shots might not be safe? | 0.938 | ||

| Q12 | How concerned are you that a shot might not prevent the disease? | 0.671 | ||

| Q6 | Children get more shots than are good for them. | 0.330 | ||

| Q8 | It is better for my child to develop immunity by getting sick than to get a shot. | 0.905 | ||

| Q9 | It is better for children to get fewer vaccines at the same time. | 0.355 |

Reliability analysis

The overall Cronbach alpha for the PACV-M-H (3) questionnaire was 0.77 (Table 3). The Cronbach alpha for each the domains “General attitudes”, “Safety and efficacy”, and “Schedule and immunity” were 0.77, 0.81, and 0.54, respectively. There were 25 completed retest questionnaires out of 151 participants (16.6%). The intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) for each of the items were excellent with ICC values ≥0.75 except Q8 with a value of 0.533.

Table 3.

Cronbach alpha for each domain and the total Cronbach alpha of the PACV-Malay.

| Factor domain | Items | Cronbach alpha for each domain | Total Cronbach alpha |

|---|---|---|---|

| General attitudes | Q5 Q13 Q14 Q15 Q16 Q17 |

0.77 | 0.77 |

| Safety and efficacy | Q10 Q11 Q12 |

0.81 | |

| Schedule and immunity | Q6 Q8 Q9 |

0.54 |

Discussion

The PACV-Malay is useful to identify VHPs. It is the first to undergo a thorough cross-cultural adaptation, translation and validation process based on recommended guidelines.17-19 This study received an encouraging response rate of >90% and the target sample size was achieved. The rigorous research process especially in translation and validation studies helps to ensure the integrity of the study instrument. This would determine the accuracy of the measurement, especially when exploring complex or subjective topics.30 The PACV-Malay has good validity and reliability. It consists of 12 items framed within three factor domains – “General attitudes”, “Safety and efficacy”, and a de novo domain “Schedule and immunity”. This is in contrast to the original questionnaire which has 15 items framed within three domains.15

During the adaptation and content validation phase, the expert panel noted two items (Q3, Q4) of the “Behavior” domain were formative questions which meant to enquire about the child’s immunization history and may be subjected to recall bias.15 The “Behavior” domain only has two items within this factor domain, and there are differences in opinions regarding the minimum number of items within a factor domain. Common recommendation is a minimum of three items per factor domain, in order for all of the subscales to be successfully identified.31,32 Some researchers quote it is possible to retain a factor with only two items for some constructs that are very narrowly defined33 and if the items are highly correlated,31,32 however rotated factors that have two or less variables should be interpreted with caution.31 Hence, these two items were excluded from psychometric analysis but retained in the final survey as part of the demography section. This study also picked up that not all delays in vaccination are intentional, for example, temporary unavailability of vaccine or accessibility problems and thus in such cases, the scoring should not be counted toward vaccine hesitancy. This was also noted in previous studies.34-36 The exclusion of the “Don’t know” answers for these questions in the scoring of the original questionnaire may also be due to the limited answer scale provided.16 Therefore, we recommend to convert items Q3 and Q4 into a numerical scale, i.e. the number of times vaccines have been delayed or refused and to include a space for parents to provide reasons for the delay or decision not to vaccinate their children. In this way, the interpretation for vaccine hesitancy would be more meaningful as the higher the number of delays or refusals would mean the parents are more vaccine hesitant.

During the translation process, one item (Q6) were interpreted differently by each translator. The same item also caused some confusion amongst respondents during face validation, resulting in amendments and repeated face validation process. The respondents were not clear with the objective of the statement and found it to be more of a linguistic issue. This is most likely because there is no direct translation from English of the “more shots than are good for them” expression. This problem was also noted in another translation study.37 However, after the expert panel changed the statement and added the word “bilangan” it improved the understandability. It was not surprising though as the original developer also had to make some changes to the same item during their validation process.14 Another local study have also reported some discrepancies during their translation process however it was not detailed out which item was involved.38

The validity analysis revealed a new domain that arose de novo which we labeled as “Schedule and immunity”. Although the PACV has been translated to other languages such as Italian and Spanish, psychometric analysis is yet to be conducted for the translated questionnaires.36,37 It would be interesting to compare the results then. The new domain comprised of items Q6, Q8 and Q9. These three items were noted to reflect parents’ concerns regarding amount and timing of childhood vaccinations. It was not surprising as items Q6 and Q9 were initially from one other item during the first development of the questionnaire before it was separated to better capture the parents’ concerns regarding time needed to complete childhood immunization.14 The original validation study did not include a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) model, therefore there may be limitations to its current three factor domain structure. The original developer had also acknowledged that this questionnaire would need to be validated prior to use in other setting, and that there may be an expected difference in results.15-16

During analysis, one item (Q7) did not load on any of the factors. As we reflect back on the inter-item correlation matrix, this item also had borderline result with a highest correlation of 0.295, and in the communalities table, this item had the lowest value of 0.127. In a previous study, item Q7 was also one of the five items that did not statistically discriminate between hesitant and non-hesitant responses.15 In view of all these supportive reasons, item Q7 was considered to be deleted. Only one item (Q14) was noted to have cross-loading, and it was considered to be in Factor 1 where it loaded highest.

The PACV-Malay is stable and reliable over time. All of the items had excellent ICC values of ≥0.75 except Q8 with a value of 0.533, which is considered fair.29 The PACV-Malay has an overall Cronbach alpha of 0.77 which is comparable to Mohd Azizi et al. with Cronbach alpha of 0.79 but lower than Napolitano et al. with Cronbach alpha of 0.91.36,38 The original PACV did not provide the overall Cronbach alpha. The Cronbach alpha for the subdomains of PACV-Malay is comparable to the original PACV. The new domain “Schedule and immunity” had a Cronbach alpha value of 0.54 which was still acceptable.27,28 Although most studies quote a higher threshold for Cronbach alpha, a lower value does not necessarily rejects its reliability. The inter-item correlation matrix for the items in this subdomain (Q6, Q8, Q9) were 0.33–0.39 which meant all the items correlate adequately in the construct. Furthermore, the ICC values for these items were high at 0.83–0.94 which also reflects its reliability.

The psychometric properties outcome was compared with other translation and validation studies done locally and in other countries. Many studies have documented results whereby their translated version yielded different findings from the original questionnaire which included swapping of items, item deletion and finding different factor models.18,39-41 The differences are attributed to cross-cultural and language differences. However, as the translated instruments were found to be valid and reliable despite the changes it is deemed suitable to be used in the local population. A study highlighted that the failure of the original scale shows the importance of cross-cultural adaptation, and that without such tedious process “the findings would have been misleading, even if presented with apparent precision”.18

There are several limitations to this study. The PACV-Malay was translated to formal Malay language and hence may only be utilized by those who are able to read and understand formal Malay language. Further study to translate and validate this questionnaire to Mandarin and Tamil would allow this tool to be utilized across the multi-racial population in Malaysia. In addition, the Kappa agreement or hypothesis testing for this study was unable to be carried out as none of the respondents’s child had ever been noted to have any missed vaccinations. This instrument can be further tested with confirmatory factor analysis with a bigger sample size. A scoring validation study is recommended in the future.

Conclusion

The PACV-Malay is a valid and reliable tool to identify VHPs and can be utilized in the Malaysian population. It measured different dimensions from the English version of PACV which requires further confirmatory factor analysis. Future study to determine its predictive validity for VHPs among Malaysians is also recommended.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Factor domains and items of the original PACV questionnaire and its scoring

| No | Items | Parent Response | Factor Domain | Scoring | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Is this child your first born? | Yes No |

Not applicable | Not applicable | |

| Q2 | What is your relationship to this child? | Mother Father Other:__________ |

Not applicable | Not applicable | |

| Q3 | Have you ever delayed having your child get a shot for reasons other than illness or allergy? | Yes No Don’t know |

Behavior | Yes = 2 No = 0 Don’t know = Excluded |

|

| Q4 | Have you ever decided not to have your child get a shot for reasons other than illness or allergy? | Yes No Don’t know |

Behavior | Yes = 2 No = 0 Don’t know = Excluded |

|

| Q5 | How sure are you that following the recommended shot schedule is a good idea for your child? | Response category on a 0–10 scale, with 0 being ‘notat all sure’ and 10 being ‘completely sure’ | General Attitudes | 0 – 5 = 2 6 – 7 = 1 8 – 10 = 0 |

|

| Q6 | Children get more shots than are good for them. | 5 point Likert scale 1 = Strongly agree 2 = Agree 3 = Not sure 4 = Disagree 5 = Strongly disagree |

General Attitudes | 1 – 2 = 2 3 = 1 4 – 5 = 0 |

|

| Q7 | I believe that many of the illnesses that shots prevent are severe. | 5 point Likert scale 1 = Strongly agree 2 = Agree 3 = Not sure 4 = Disagree 5 = Strongly disagree |

General Attitudes | 1 – 2 = 0 3 = 1 4 – 5 = 2 |

|

| Q8 | It is better for my child to develop immunity by getting sick than to get a shot. | 5 point Likert scale 1 = Strongly agree 2 = Agree 3 = Not sure 4 = Disagree 5 = Strongly disagree |

General Attitudes | 1 – 2 = 2 3 = 1 4 – 5 = 0 |

|

| Q9 | It is better for children to get fewer vaccines at the same time. | 5 point Likert scale 1 = Strongly agree 2 = Agree 3 = Not sure 4 = Disagree 5 = Strongly disagree |

Safety and Efficacy | 1 – 2 = 2 3 = 1 4 – 5 = 0 |

|

| Q10 | How concerned are you that your child might have a serious side effect from a shot? | 5 point Likert scale 1 = Not at all concerned 2 = Not too concerned 3 = Not sure 4 = Somewhat concerned 5 = Very concerned |

Safety and Efficacy | 1 – 2 = 0 3 = 1 4 – 5 = 2 |

|

| Q11 | How concerned are you that any one of the childhood shots might not be safe? | 5 point Likert scale 1 = Not at all concerned 2 = Not too concerned 3 = Not sure 4 = Somewhat concerned 5 = Very concerned |

Safety and Efficacy | 1 – 2 = 0 3 = 1 4 – 5 = 2 |

|

| Q12 | How concerned are you that a shot might not prevent the disease? | 5 point Likert scale 1 = Not at all concerned 2 = Not too concerned 3 = Not sure 4 = Somewhat concerned 5 = Very concerned |

Safety and Efficacy | 1 – 2 = 0 3 = 1 4 – 5 = 2 |

|

| Q13 | If you had another infant today, would you want him/her to get all the recommended shots? | Yes No Don’t know |

General Attitudes | Yes = 0 No = 2 Don’t know = 1 |

|

| Q14 | Overall, how hesitant about childhood shots would you consider yourself to be? | 5 point Likert scale 1 = Not at all hesitant 2 = Not too hesitant 3 = Not sure 4 = Somewhat hesitant 5 = Very hesitant |

General Attitudes | 1 – 2 = 0 3 = 1 4 – 5 = 2 |

|

| Q15 | I trust the information I receive about shots. | 5 point Likert scale 1 = Strongly agree 2 = Agree 3 = Not sure 4 = Disagree 5 = Strongly disagree |

General Attitudes | 1 – 2 = 0 3 = 1 4 – 5 = 2 |

|

| Q16 | I am able to openly discuss my concerns about shots with my child’s doctor. | 5 point Likert scale 1 = Strongly agree 2 = Agree 3 = Not sure 4 = Disagree 5 = Strongly disagree |

General Attitudes | 1 – 2 = 0 3 = 1 4 – 5 = 2 |

|

| Q17 | All things considered, how much do you trust your child’s doctor? | Response category on a 0–10 scale, with 0 being ‘do not trust at all’ and 10 being ‘completely trust’ | General Attitudes | 0 – 5 = 2 6 – 7 = 1 8 – 10 = 0 |

|

Appendix 2. Floor and ceiling effects

| Item number | Items | N (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly agree | Agree | Not sure | Disagree | Strongly disagree | ||

| Q6 | Children get more shots than are good for them. | 13 (8.6) |

38 (25.2) |

49 (32.5) |

43 (28.5) |

8 (5.3) |

| Q7 | I believe that many of the illnesses that shots prevent are severe. | 38 (25.2) |

95 (62.9) |

15 (9.9) |

3 (2.0) |

0 |

| Q8 | It is better for my child to develop immunity by getting sick than to get a shot. | 8 (5.3) |

20 (13.2) |

27 (17.9) |

69 (45.7) |

27 (17.9) |

| Q9 | It is better for children to get fewer vaccines at the same time. | 2 (1.3) |

30 (19.9) |

65 (43.0) |

43 (28.5) |

11 (7.3) |

| Q15 | I trust the information I receive about shots. | 45 (29.8) |

97 (64.2) |

9 (6.0) |

0 | 0 |

| Q16 |

I am able to openly discuss my concerns about shots with my child’s doctor. |

50 (33.1) |

94 (62.3) |

4 (2.6) |

3 (2.0) |

0 |

| |

|

Not at all concerned |

Not too concerned |

Not sure |

Somewhat concerned |

Very concerned |

| Q10 | How concerned are you that your child might have a serious side effect from a shot? | 14 (9.3) |

57 (37.7) |

22 (14.6) |

41 (27.2) |

17 (11.3) |

| Q11 | How concerned are you that any one of the childhood shots might not be safe? | 16 (10.6) |

41 (27.2) |

47 (31.1) |

34 (22.5) |

13 (8.6) |

| Q12 |

How concerned are you that a shot might not prevent the disease? |

20 (13.2) |

40 (26.5) |

38 (25.2) |

36 (23.8) |

17 (11.3) |

| |

|

Not at all hesitant |

Not too hesitant |

Not sure |

Somewhat hesitant |

Very hesitant |

| Q14 | Overall, how hesitant about childhood shots would you consider yourself to be? | 60 (39.7) |

60 (39.7) |

21 (13.9) |

10 (6.6) |

0 |

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Universiti Teknologi MARA Malaysia under grant no. 600-RMI/DANA 5/3/LESTARI (38/2015).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Director General of Health, Malaysia for permission to publish this work. We also want to express our appreciation to Dr. Douglas J. Opel for the permission to use the PACV questionnaire. We are grateful to Dr Rofina Abdul Rahim, Dr Hamidah Abd Latip and all support staff of the Maternal and Child Health clinic of Klinik Kesihatan Seksyen 19 for assistance during data collection. We also acknowledge Dr Noor Shafina Mohd Nor for her contribution toward the study.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interests.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . WHO in 60 years: a chronology of public health milestones. Geneva (Switzerland); 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Vaccine safety basics. Geneva (Switzerland); 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdul-Razak S, Azzopardi PS, Patton GC, Mokdad AH, Sawyer SM.. Child and adolescent mortality across Malaysia’s epidemiological transition: A systematic analysis of global burden of disease data. J Adolesc Heal. 2017;61:424–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.United Nations Development Program . Malaysia Millennium development goals report 2015. Wilayah Persekutuan, Malaysia; 2016. ISBN No. 978-983-3904-17-4. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Smith DMD, Paterson P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: A systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine. 2014;32:2150–59. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borba RCN, Vidal VM, Moreira LO. The re-emergency and persistence of vaccine preventable diseases. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2015;87:1311–22. doi: 10.1590/0001-3765201520140663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ministry of Health Malaysia . Health Facts 2017. Wilayah Persekutuan (Malaysia); 2017.

- 8.Ministry of Health Malaysia . Health facts 2016. Wilayah Persekutuan (Malaysia); 2016.

- 9.Ministry of Health Malaysia . Health facts 2015. Wilayah Persekutuan (Malaysia); 2015.

- 10.Ministry of Health Malaysia . Health facts 2014. Wilayah Persekutuan (Malaysia); 2014.

- 11.Thompson G Measles and MMR statistics. Library House of Commons Social and General Statistics. London (United Kingdom); 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacDonald NE. SAGE working group on vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33:4161–64. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Schulz WS, Chaudhuri M, Zhou Y, Dube E, Schuster M, Macdonald NE, Wilson R. Measuring vaccine hesitancy: the development of a survey tool the SAGE working group on vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine. 2015;33:4165–75. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Opel DJ, Mangione-Smith R, Taylor JA, Korfiatis C, Wiese C, Catz S, Martin D. Development of a survey to identify vaccine-hesitant parents: the parent atttitudes about childhood vaccines survey. Vaccine. 2011;7:419–25. doi: 10.4161/hv.7.4.14120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Opel DJ, Taylor JA, Mangione-Smith R, Solomon C, Zhao C, Catz S, Martin D. Validity and reliability of a survey to identify vaccine-hesitant parents. Vaccine. 2011;29:6598–605. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Opel DJ, Taylor JA, Zhou C, Catz S, Myaing M, Mangione-Smith R. The relationship between parent attitudes about childhood vaccines survey scores and future child immunization status. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:1065. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, LM B, de Vet HCW. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments : an international Delphi study. Quality of Life Reseach. 2010;19:539–49. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9606-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gjersing L, Caplehorn JRM, Clausen T. Cross-cultural adaptation of research instruments: language, setting, time and statistical considerations. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wild D, Grove A, Martin M, Eremenco S, McElroy S, Verjee-Lorenz A, Erikson P. Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) measures: report of the ISPOR task force for translating adaptation. Value Heal. 2005;8:94–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.04054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Vaus D. Surveys in social research. 3rd ed. North Sydney (Australia): Allen and Unwin Pty Ltd; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anthoine E, Moret L, Regnault A, Sbille V, Hardouin J-B. Sample size used to validate a scale: A review of publications on newly-developed patient reported outcomes measures. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12955-014-0176-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gorsuch RL. Factor analysis. 2rd ed. Hillsdale (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1983. ISBN No. 978-0898592023. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hogarty KY. The quality of factor solutions in exploratory factor analysis: the influence of sample size, communality, and overdetermination. Educ Psychol Meas. 2005;65:202–26. doi: 10.1177/0013164404267287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, Knol DL, Ostelo RWJG, Bouter LM, de Vet HCW. Rating the methodological quality in systematic reviews of studies on measurement properties : a scoring system for the COSMIN checklist. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:651–57. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9960-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bollen KA. A new incremental fit index for general structural equation models. Sociol Methods Res. 1989;17:303–16. doi: 10.1177/0049124189017003004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bentler P. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull. 1990;107:238–46. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taber KS. The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res Sci Educ. 2018;48:1273–96. doi: 10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmitt N. Uses and abuses of coefficient alpha. Psychol Assess. 1996;8:350–53. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.8.4.350. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychol Assess. 1994;6:284–90. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.284. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parsian N, TD AM. Developing and validating a questionnaire to measure spirituality: A psychometric process. Glob J Health Sci. 2009;1:2–11. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v1n1p2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raubenheimer JE. An item selection procedure to maximise scale reliability and validity. SA J Ind Psychol. 2004;30:59–64. doi: 10.4102/sajip.v30i4.168. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yong AG, Pearce S. A beginner’s guide to factor analysis: focusing on exploratory factor analysis. Tutor Quant Methods Psychol. 2013;9:79–94. doi: 10.20982/tqmp.09.2.p079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bergkvist L, Rossiter J. Tailor-made single-item measures of doubly concrete constructs. Int J Advert. 2009;28:607–21. doi: 10.2501/S0265048709200783. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gust DA, Darling N, Kennedy A, Schwartz B. Parents with doubts about vaccines: which vaccines and reasons why. Pediatrics. 2008;122:718–25. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Azhar SS, Nirmal K, Nazarudin S, Rohaizat H, Noor AA, Rozita H. Factors influencing childhood immunization defaulters in Sabah, Malaysia. Int Med J Malaysia. 2012;11:17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Napolitano F, D’ A, Italo A, Angelillo F. Investigating Italian parents’ vaccine hesitancy: a cross-sectional survey. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14:1558–65. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.146394310.1080/21645515.2018.1463943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cunningham RM, Kerr GB, Orobio J, Munoz FM, Correa A, Villafranco N, Monterrey AC, Opel DJ, Boom JA. Development of a Spanish version of the parent attitudes about childhood vaccines survey. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2019:1–24. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2019.1578599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohd Azizi FS, Kew Y, Moy FM. Vaccine hesitancy among parents in a multi-ethnic country, Malaysia. Vaccine. 2017;35:2955–61. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.An J, Kim YH, Cho S. Validation of the Korean version of the avoidance endurance behavior questionnaire in patients with chronic pain. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16:10–14. doi: 10.1186/s12955-018-1014-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen WS, Haniff J, Siau CS, Seet W, Loh SF, Abd Jamil MH, Sa’at N, Baharum N. Translation, cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Malay version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) in Malaysia. Int J Soc Sci Stud. 2014;2:66–74. doi: 10.11114/ijsss.v2i2.309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jalaludin MY, Fuziah MZ, Hong JYH, Mohamad Adam B, Jamaiyah H. Reliability and validity of the revised summary of diabetes self-care activities (SDSCA) for Malaysian children and adolescents. Malaysian Fam Physician. 2012;7:10–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]