ABSTRACT

Given the link between vaccine hesitancy and vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks, it is critical to examine the cognitive processes that contribute to the development of vaccine hesitancy, especially among parents of adolescents. We conducted a secondary analysis of baseline data from a two-phase randomized trial on human papillomavirus to investigate how vaccine hesitancy and intent to vaccinate are associated with six decision-making factors: base rate neglect, conjunction fallacy, sunk cost bias, present bias, risk aversion, and information avoidance. We recruited 1,413 adults residing in the United States with at least one daughter aged 9–17 years old through an online survey on Amazon Mechanical Turk. Vaccine hesitancy, intent to vaccinate, and susceptibility to cognitive biases was measured through a series of brief questionnaires. 1,400 participants were in the final analyzed sample. Most participants were white (74.1%), female (71.6%), married (75.3%), and had a college or graduate/professional education (88.8%). Conjunction fallacy, sunk cost bias, information avoidance, and present bias may be associated with vaccine hesitancy. Intent to vaccinate may be associated with information avoidance. These results suggest that cognitive biases play a role in developing parental vaccine hesitancy and vaccine-related behavior.

KEYWORDS: Vaccines, vaccine hesitancy, cognitive bias, heuristics, HPV, adolescent

Introduction

Vaccines are one of the most successful public health interventions, preventing an estimated 20 million cases of preventable disease and over 40,000 deaths for each United States birth cohort .1 The economic savings from vaccinations include $14 billion in direct healthcare costs and $69 billion in societal costs .1 However, an upward trend in vaccine exemptions and recent outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases, such as the recent measles outbreak,2 indicates an increase in vaccine hesitancy in some individuals.3,4 Additionally, a recent study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that 10% of parents in the United States are opposed to compulsory vaccination.5 Parents who oppose compulsory vaccination are more likely to have low confidence in the safety and protective value of vaccines.5 While human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination is not universally compulsory in the United States, there is a possibility that the same negative attitudes parents have toward compulsory vaccines may also impact their attitudes about the HPV vaccine, and may therefore limit HPV vaccine uptake. Therefore, addressing HPV-related vaccine hesitancy among parents may be critical to expand HPV vaccine coverage.

Adequate human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine coverage is necessary for adolescents, since this group accounts for most incident cases of HPV. HPV is so prevalent that nearly all sexually active individuals are infected at some point during their lives.6 While most HPV infections resolve without intervention, high-risk strains of this virus cause the majority of cervical, oropharyngeal, and genital cancers.7 Therefore, high HPV vaccine uptake is critical to reduce the burden of HPV-related cancer morbidity and mortality.

Although HPV vaccine coverage in the United States is improving, current coverage rates are still below the goal of 80% set by Healthy People 2020.8 A variety of parental factors are associated with low HPV vaccine uptake, including lack of knowledge about the vaccine, low perception of HPV risk, and other vaccine attitudes.9 While inadequate knowledge about HPV and its vaccine are often cited as a reason for low uptake, providing parents with information about HPV does not appear to improve vaccine acceptance.10 Some evidence suggests that attempts to correct vaccine misinformation can actually backfire, reinforcing beliefs that vaccines are harmful and reducing intent to vaccinate.11 Thus, parents’ attitudes and perceptions of risk may be better targets to combat hesitancy.

Vaccine-hesitant individuals hold attitudes and beliefs that lead to concerns about vaccinating themselves or their children, which may in turn lead to refusing or delaying some or all recommended vaccines.3 Multiple factors contribute to vaccine hesitancy, including lack of trust in the healthcare system or care providers, lack of knowledge about vaccines and vaccine-preventable diseases, and a lack of perceived need for vaccines.12,13 While parental vaccine hesitancy has been explored along several sociodemographic and psychosocial dimensions (e.g. education, race/ethnicity, peer group norms), basic underlying cognitive and decision-making characteristics such as temporal orientation and risk aversion are also likely associated with vaccine attitudes and intentions, and may be critical but understudied moderators of intervention effects.10,14–18

In this study, we explore six common heuristics and cognitive biases that we hypothesize may be associated with parental vaccine hesitancy and intentions to vaccinate for the HPV vaccine. Heuristics, a concept in decision-making research, describe a simplified cognitive approach to solving problems and forming judgments.19 Decision-making associated with heuristics simplify and expedite complex problem-solving; however, these rules can sometimes deviate from logic, probability, or rational choice theory.19 These logical errors in decision-making are referred to as cognitive biases. While some researchers have theorized that cognitive biases can shape parents’ vaccine-related decision-making processes, few have investigated how specific biases individually impact vaccine hesitancy.20,21 To broaden the current understanding of this topic, this study aims to investigate how both hesitancy toward vaccines and parental intent to have their child receive the HPV vaccine are associated with these decision-making factors (Table 1).

Table 1.

Definitions for cognitive biases.

| Cognitive Bias | Definition |

|---|---|

| Base Rate Neglect | Individuals focus more on specific information and ignore general information about events22 |

| Conjunction Fallacy | Occurs when an individual thinks a specific condition is more likely than a general condition23 |

| Sunk Cost Fallacy | Individuals are compelled to continue a behavior or efforts toward a goal because they have previously invested resources (time, money, etc.) that cannot be recovered24 |

| Present Bias | The tendency to give stronger weight to more-immediate payoffs than long-term payoffs25 |

| Risk Aversion | The preference to invest in an opportunity with lower returns and known risks rather than an opportunity with higher returns, but greater or unknown risk26 |

| Information Avoidance | The preference to not to obtain knowledge that is freely available, especially if that knowledge is unwanted or unpleasant27 |

Methods

We conducted a secondary analysis of baseline data from a two-phase randomized trial to investigate how vaccine hesitancy and intent to vaccinate among participants are associated with six decision-making factors: base rate neglect, conjunction fallacy, sunk cost bias, present bias, risk aversion, and information avoidance (Table 1).28 These six factors were selected for prior studies of smoking behavior and vaccine hesitancy based on conceptual relevance, existing valid instruments, and relative ease of measurement in a brief online survey.22–27,29,30

To summarize the original randomized trial, the participants’ vaccine confidence and intent to vaccinate were measured before and after receiving a cervical cancer-salient message encouraging HPV vaccination, compared to control messages.These messages ultimately did not have an effect on vaccine confidence or intent to vaccinate.28 It should be noted that the bias measures utilized in the current analysis were only included in the online survey at baseline; therefore, the results of thesecondary analysis are not affected by the primary study intervention.

We recruited adult men and women residing in the United States with at least one daughter 9–17 years old who had not completed the full HPV vaccine series, which included both unvaccinated girls and girls who had received at least one dose, but not the full HPV series. This survey was conducted through Amazon Mechanical Turk (mTurk). Eligibility and compensation are as detailed in Porter et al., 2018.28 The Emory University Institutional Review Board approved all study activities (Study #00087211). The study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov, under reference number NCT03002324.

The primary outcome measure of this analysis, overall vaccine hesitancy, was measured by the Vaccine Confidence Scale (VCS).31 The VCS is an 8-item questionnaire measuring the perceived benefits and perceived harms of vaccinating one’s teenager, as well as the parent’s trust in their relationship with their healthcare providers. Likert-type scales are used to measure a parent’s agreement with statements about vaccines, (e.g. “Vaccines are safe”) with higher scores relating to positive attitudes toward vaccines for all but two items. These two harm-related items were reverse-coded. VCS scores were calculated by averaging the numeric scores for all 8 questions. Lower scores on this measure indicate greater vaccine hesitancy.

The secondary outcome measure was intent to vaccinate with the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, which asked participants one of two questions: if they intended to vaccinate their child (if not previously vaccinated) or if they intended to complete the full HPV vaccine series (if the child had already received at least one dose). Key sociodemographic data was also collected (Table 2). Cognitive biases were measured using previously-validated questionnaires, adapted in some cases for our survey (Appendix A).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of study sample.

| n | Mean (SD)* or % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Participant Gender | |||

| Male | 388 | 27.46 | |

| Female | 1012 | 71.62 | |

| Prefer Not to Answer | 13 | 0.92 | |

| Participant Age, Years* | 39.4 (7.3) | ||

| Participant Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White | 1047 | 74.1 | |

| African American | 102 | 7.2 | |

| Asian | 78 | 5.5 | |

| Hispanic | 54 | 3.8 | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 23 | 1.6 | |

| Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 3 | 0.2 | |

| Other/Multi-racial | 106 | 7.5 | |

| Participant Marital Status | |||

| Single, Never Married | 127 | 9.0 | |

| Married | 1064 | 75.3 | |

| Widowed/Divorced/Separated | 222 | 15.7 | |

| Household Income | |||

| Less than $25,000 | 170 | 12.0 | |

| $25,000-$34,999 | 188 | 13.3 | |

| $35,000-$49,999 | 215 | 15.2 | |

| $50,000-$74,999 | 307 | 21.7 | |

| $75,000-$99,999 | 262 | 18.5 | |

| Over $100,000 | 271 | 19.2 | |

| Number of children in household | |||

| 1 child | 222 | 15.7 | |

| 2 children | 558 | 39.5 | |

| 3 children | 325 | 23.0 | |

| 4 or more children | 308 | 21.8 | |

| Participant Education Level | |||

| High School or GED | 159 | 11.3 | |

| College Degree | 953 | 67.5 | |

| Graduate or Professional Degree | 301 | 21.3 | |

| Daughter’s Age | |||

| 9–11 years old | 488 | 34.5 | |

| 12–14 years old | 457 | 32.3 | |

| 15–17 years old | 468 | 33.1 | |

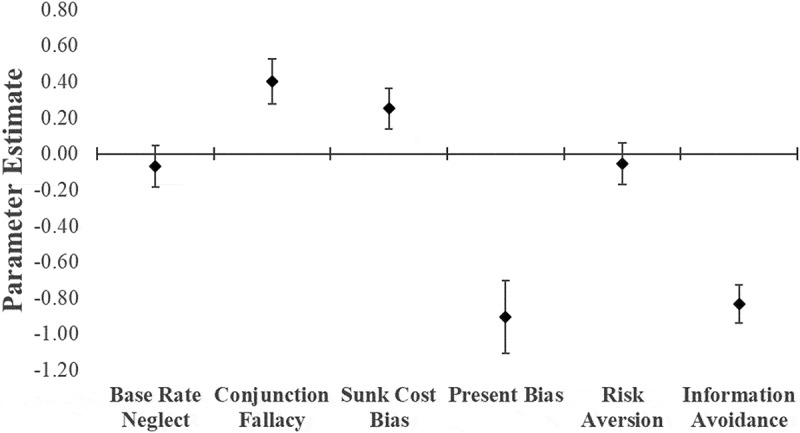

The association between each cognitive bias and VCS score was assessed using six separate univariate linear regression models, with VCS score as the outcome variable. Model results were reported as beta coefficients with confidence estimates (Figure 1). A sensitivity analysis was conducted using multinomial logistic regression for each final cognitive bias model by dividing VCS score into three categories [Low (VCS ≤ 6), Medium (6 < VCS ≤ 8), and High (VCS > 8], based off the cut-points established in Gilkey et al., 2016.32 High VCS score was used as the reference group. We used multinomial logistic regression because the VCS score outcomes violate the proportional odds assumption for an ordered logit.

Figure 1.

Parameter estimates indicating the relationship between Vaccine Confidence Scale score and individual cognitive biases, modeled with multivariate linear regression. A positive parameter estimate indicates higher vaccine confidence, while a negative parameter estimate indicates lower vaccine confidence. Cognitive biases were coded dichotomously (Susceptible to bias vs. not susceptible); the parameter estimates indicate the change in VCS score if the bias is present, compared to if the bias is absent.

The analysis for the relationship between intent to vaccinate and the individual cognitive biases was performed using an additional six individual univariate logistic regressions, with intent to vaccinate as the outcome variable. The analyses in this study were completed using SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

Results

16,474 participants from Amazon Mechanical Turk were assessed for eligibility, with 1,481 participants eligible for entry into the study. Of those, 1,413 participants participated in the first phase survey. The majority of participants were white (74.1%), female (71.6%), and married (75.3%). Most (88.8%) of the sample had a college or graduate/professional education (Table 2). Participants who responded with “Prefer not to answer” for their gender were excluded in the final analysis due to low sample size (n = 13). The mean VCS scores of each bias’ susceptibility condition is shown (Table 3).

Table 3.

Vaccine hesitance scores by cognitive bias susceptibility.

| N | Mean (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Base Rate Neglect | |||

| Susceptible | 965 | 7.28 (2.00) | |

| Not Susceptible | 448 | 7.37 (1.92) | |

| Conjunction Fallacy | |||

| Susceptible | 1085 | 7.41 (1.95) | |

| Not Susceptible | 328 | 6.99 (2.05) | |

| Sunk Cost Bias | |||

| Susceptible | 443 | 7.49 (1.85) | |

| Not Susceptible | 970 | 7.23 (2.03) | |

| Present Bias | |||

| Susceptible | 105 | 6.44 (1.77) | |

| Not Susceptible | 1300 | 7.38 (1.98) | |

| Risk Aversion | |||

| Susceptible | 1003 | 7.29 (1.99) | |

| Not Susceptible | 410 | 7.36 (1.95) | |

| Information Avoidance | |||

| Susceptible | 552 | 6.80 (2.02) | |

| Not Susceptible | 861 | 7.64 (1.88) | |

We found positive associations between VCS score and 2 of the cognitive biases: conjunction fallacy and sunk cost bias; information avoidance and present bias were found to have a negative association with VCS score (Figure 1). Base rate neglect and risk aversion were not significantly associated with VCS score. The beta estimates are interpreted as VCS score differences between the bias-susceptible and the non-susceptible participants. More present-biased participants scored, on average, 0.70 points lower on the VCS than less present-biased participants. The sensitivity analyses showed evidence that the associations for most of the cognitive biases are robust to different treatments of the VCS outcome (Table 4).

Table 4.

Sensitivity analysis for the association of individual cognitive biases with vaccine confidence scale score.

| Variable | VCS Score Category | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base Rate Neglect | Low | 1.12 | 0.84 | 1.48 |

| Medium | 1.07 | 0.82 | 1.39 | |

| High | 1.00 | - | - | |

| Conjunction Fallacy | Low | 0.59 | 0.43 | 0.80 |

| Medium | 0.77 | 0.57 | 1.04 | |

| High | 1.00 | - | - | |

| Sunk Cost Bias | Low | 0.72 | 0.54 | 0.96 |

| Medium | 0.87 | 0.67 | 1.13 | |

| High | 1.00 | - | - | |

| Information Avoidance | Low | 2.92 | 2.22 | 3.84 |

| Medium | 1.79 | 1.38 | 2.32 | |

| High | 1.00 | - | - | |

| Present Bias | Low | 3.74 | 2.21 | 6.33 |

| Medium | 2.14 | 1.24 | 3.71 | |

| High | 1.00 | - | - | |

| Risk Aversion | Low | 1.01 | 0.75 | 1.35 |

| Medium | 0.92 | 0.70 | 1.21 | |

| High | 1.00 | - | - | |

Note: VCS Scores were divided between Low (VCS ≤ 6), Medium (6 < VCS ≤ 8), and High (VCS > 8). Lower scores indicate greater hesitancy. Odds ratios indicate the odds of susceptibility to each cognitive bias between levels of vaccine hesitancy, modeled using multinomial logistic regression with “High” vaccine confidence scores as the reference group.

Among participants whose daughters had not completed the HPV vaccine series, the odds of intending to vaccinate are lower among participants who experience information avoidance (Table 5). There was 13% lower odds of intending to vaccinate for each standard deviation increase in information avoidance. The odds of intending to vaccinate do not differ by susceptibility for the remaining biases.

Table 5.

Estimated odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the association of individual cognitive biases with intent to vaccinate (N = 1400).

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base Rate Neglect | 0.99 | 0.77 | 1.26 |

| Conjunction Fallacy | 0.90 | 0.69 | 1.18 |

| Sunk Cost Bias | 1.02 | 0.80 | 1.30 |

| Information Avoidance | 0.76 | 0.60 | 0.96 |

| Present Bias | 1.20 | 0.77 | 1.88 |

| Risk Aversion | 0.85 | 0.66 | 1.09 |

Note: Cognitive biases were coded dichotomously (Susceptible to bias vs. not susceptible); the OR indicates the odds of intending to vaccinate if the bias is present vs if the bias is absent.

Discussion

This study found that parental susceptibility to established cognitive biases is associated with vaccine hesitancy. We found that the presence of certain cognitive biases – conjunction fallacy and sunk cost bias – was associated with lower vaccine hesitancy. Information avoidance and present bias were postively associated with parental vaccine hesitancy. For our secondary outcome, lower intent to vaccinate was associated with information avoidance.

Attitudes and beliefs about vaccination are crucial to achieving adequate vaccine coverage, but the specific cognitive processes underlying the development of vaccine hesitancy require continued research. Previous research has looked at omission bias, a cognitive heuristic not studied here. It measures a tendency to prefer harms caused by omissions or inaction over harms caused by actions. In this research, vaccine-hesitant participants were more likely to exhibit omission bias, which was associated with a belief that vaccinating posed a greater danger than not vaccinating.33 Otherwise, previous evidence on the existence of a relationship between cognitive biases and vaccine hesitancy is limited. This study added evidence that relationships do exist between cognitive biases and vaccine hesitancy, and that specific biases may be related to improved or diminished attitudes about vaccines.

Although this analysis is meant to serve as a broad examination of cognitive biases in a vaccine context, previous vaccine hesitancy research can be evaluated to form potential hypotheses for the results observed here. In an earlier study of parental vaccine hesitancy, there was no evidence of an association between parental vaccine hesitancy and adolescent vaccine uptake.34 This may explain the seemingly contradictory results for conjunction fallacy and sunk cost bias – the cognitive biases that are associated with lower vaccine hesitancy, but do not appear to influence intent to vaccinate; in other words, vaccine attitudes might not necessarily impact vaccine behavior.

This study was limited primarily by the original randomized trial outcomes’ focus on only the HPV vaccine. Our sample was restricted to a population of parents of daughters who are eligible for the HPV vaccine, and limits generalizability to parents of male children and hesitancy toward vaccines targeting other diseases. The stigma toward the HPV vaccine, fostered by the cultural stigma toward sexually transmitted diseases and fear that HPV vaccination will cause sexual disinhibition, may impact the nature and degree of hesitancy in this group, especially among parents of daughters.10 Additionally, our sample may have some degree of selection bias incurred by the use of an online survey platform, since participants are self-selected and the format excludes those with limited or no internet access. However, a more homogenous parent population may be desirable for an exploratory study such as this one. Because each cognitive bias in this study was individually regressed with VCS score, the interrelation between the cognitive biases cannot be assessed with this particular analysis. Furthermore, it is unclear if susceptibility to cognitive biases influences vaccine attitudes or if some third factor influences both susceptibility and attitudes. Finally, it should be noted that our sample includes parents of both unvaccinated and under-vaccinated daughters. For the purpose of our analyses, these groups were consolidated into one category – parents of daughters who had not completed the full HPV vaccine series – since vaccine hesitancy or lesser intent to vaccinate can result in both non-vaccination and under-vaccination. This being said, other factors that may influence vaccine decision-making (e.g. convenience, perceptions of risk, etc.) may be different between parents considering the initial vaccine dose for their child and parents considering vaccine completion; thus, whatever influence some cognitive biases may have on vaccine hesitancy might differ between these groups. Later studies may want to distinguish between these two vaccination categories.

Future research should investigate the relationships between vaccine hesitancy and each of the cognitive biases in this study in greater depth. Such studies could determine whether these biases can form a cognitive phenotype for vaccine-hesitant participants, and if so, if this phenotype has influence on vaccine-related behaviors, such as vaccination of self or one’s children. Previous research has shown that social networks play an important role in parents’ vaccination decision-making, and that vaccine-hesitant parents create social networks together and deviate from the norm of vaccination .35 Thus, consequent studies should investigate whether these networks of vaccine-hesitant parents display similar cognitive biases and, if so, whether these biases have influence on their vaccine attitudes and intentions.

Conclusions

Several cognitive biases may be associated with vaccine hesitancy, including conjunction fallacy, sunk cost bias, present bias, and information bias, although some of these associations may be contradictory. Additionally, intent to vaccinate is lower among participants who are susceptible to information avoidance. These results suggest that cognitive biases play a role in both the development of parental vaccine hesitancy and vaccine-related behavior. Future studies should be conducted to further investigate how these human decision-making processes influence vaccine hesitancy, especially among a variety of vaccines and populations.

Appendix A. Cognitive Bias Measures

Base rate neglect was measured with a question developed by Kahneman and Tversky.22 The prompt describes a group of 100 women, in which 70 are supermarket cashiers and 30 are librarians, followed by a description of a detail-oriented and quiet woman in the group named Ashley. Participants rate the chances of Ashley being a supermarket cashier using a slider from 0% to 100%. Base rate neglect was coded as present if the response was <70%.

Conjunction fallacy was also measured with a question developed by Kahneman and Tversky and modified for this study, where a woman named Brittany is described as outspoken and social-justice-oriented.23 Participants rank the probability of 5 scenarios related to Brittany from 1 to 5, with 1 as “Most probable” and 5 as “Least probable”. Conjunction fallacy was coded as present if, within these 5 scenarios, the participant ranks “Brittany is a bank teller and active in the feminist movement” as more probable than “Brittany is a bank teller”.

Sunk cost fallacy was measured with two related questions.24 Both prompts refer to a scenario where the participant imagines watching 5 minutes of a boring movie in a hotel and must decide whether to continue watching the movie or to switch channels on the television. In the first scenario, the participant has paid $6.95 for the movie; in the second scenario, the movie was free. Sunk cost fallacy is coded as present if the participant indicates that they would continue watching if they paid to watch the movie but would switch channels if the movie were free. This suggests that the participant would choose to continue a behavior due to having made a previous investment, even if continuing that behavior is not beneficial and requires continued investment of time and resources. In other cases, including if the participant indicates they would switch if they paid but would continue watching if the movie were free, participants were not considered to be susceptible to the sunk cost fallacy.

Present bias was measured with a 7-item questionnaire, each question presenting two choices about receiving money now or receiving money later, i.e. would the participant prefer to “Receive a $5 gift card today or a $15 gift card in five days”.25 Consecutive questions increased the “current” payout from $5 to $17 in increments of $2, while the money received in five days remained stable at $15. Susceptibility to present bias tends to be greater if participants prefer to receive less money now instead of more money later. We coded present bias as a dichotomous variable due to non-normal distribution of responses. In this study, the bias was present if participants preferred less than half the maximum payout now than $15 in five days, indicating that the participant has a preference for immediate payoffs at the expense of better long-term outcomes

Risk aversion was measured by presenting a list of six gambles, each with two potential equally likely payoffs (e.g. a coin flip).26 The first gamble presented two equal payoffs of $10, with subsequent gambles having gradually more unequal payoffs, up to “Heads: $2.50, Tails: $24”. Participants chose which gamble to take. Risk aversion scores tend to be greater in participants preferring more equal payoffs than riskier, but potentially greater, payoffs. We coded risk aversion as a dichotomous variable due to the non-normal distribution of responses in our sample. Risk aversion was present if participants chose either of the two least risky gambles (Heads: $10, Tails: $10 and Heads: $9.50, Tails: $11). Risk averse participants were not willing to pay a risk premium for a potentially higher pay out.

Information avoidance was measured with a 6-item questionnaire relating to whether the participant would want to avoid potentially distressing knowledge (e.g. “I would avoid learning whether my partner is cheating on me”).27 The original health-related items in this questionnaire were modified by replacing them with items relating to HPV and cervical cancer. The responses to each statement are scaled from 1 (“Strongly Disagree”) to 5 (“Strongly Agree”). Information avoidance scores were calculated by reverse coding the responses for the two “want to know” questions, then calculating the sum of the scores for all 6 questions. Since this was an interval measure, the scores were dichotomized at the 66th percentile; scores over this cutoff were coded as susceptible.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- 1.Zhou F, Shefer A, Wenger J, Messonnier M, Wang LY, Lopez A, Moore M, Murphy TV, Cortese M, Rodewald L, et al. Economic evaluation of the routine childhood immunization program in the United States, 2009. Pediatrics. 2014;133(4):577–85. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel M, Lee AD, Redd SB, Clemmons NS, McNall RJ, Cohn AC, Gastañaduy PA.. Increase in measles cases — United States, January 1–April 26, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:402–04. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6817e1external icon. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6817e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dubé E, Laberge C, Guay M, Bramadat P, Roy R, Bettinger J. Vaccine hesitancy: an overview. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2013;9(8):1763–73. doi: 10.4161/hv.24657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Omer SB, Salmon DA, Orenstein WA, deHart MP, Halsey N. Vaccine refusal, mandatory immunization, and the risks of vaccine-preventable diseases. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(19):1981–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0806477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kennedy AM, Brown CJ, Gust DA. Vaccine beliefs of parents who oppose compulsory vaccination. Public Health Rep. 2005;120(3):252–58. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.HPV and Cancer . National cancer institute; 2019. [accessed 2019 April19]. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/infectious-agents/hpv-and-cancer?redirect=true

- 7.Sexually Transmitted Diseases Surveillance 2017 . Centers for disease control and prevention; 2018. [accessed 2019 April19]. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats17/other.htm

- 8.HPV vaccine, adolescents, 2008–2012 . HPV vaccine, adolescents, 2008–2012 | healthy People 2020; 2014. [accessed 2019 April19]. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/national-snapshot/hpv-vaccine-adolescents-2008–2012.

- 9.Dorell CG, Yankey D, Santibanez TA, Markowitz LE. Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Series Initiation and Completion, 2008–2009. Pediatrics. 2011. November;128(5):830–39. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dempsey AF. Factors that are associated with parental acceptance of human papillomavirus vaccines: a randomized intervention study of written information about HPV. Pediatrics. 2006;117(5):1486–93. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pluviano S, Watt C, Sala SD. Misinformation lingers in memory: failure of three pro-vaccination strategies. PLoS One. 2017;12(7). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salmon DA, Dudley MZ, Glanz JM, Omer SB. Vaccine hesitancy: causes, consequences, and a call to action. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(6):S391–S398. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edwards KM, Hackell JM. Countering vaccine hesitancy. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20162146–e20162146. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perkins RB, Pierre-Joseph N, Marquez C, Iloka S, Clark JA. Why do low-income minority parents choose human papillomavirus vaccination for their daughters? J Pediatr. 2010;157(4):617–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenthal SL, Rupp R, Zimet GD, Meza HM, Loza ML, Short MB, Succop PA. Uptake of HPV vaccine: demographics, sexual history and values, parenting style, and vaccine attitudes. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;43(3):239–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ford JL. Racial and ethnic disparities in human papillomavirus awareness and vaccination among young adult women. Public Health Nurs. 2011;28(6):485–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2011.00958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brewer NT, DeFrank JT, Gilkey MB. Anticipated regret and health behavior: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2016;35(11):1264–75. Health Commun. 2016 Sep;31(9):1089–96. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2015.1038774. Epub 2016 Jan 22. doi: 10.1037/hea0000294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim J, Nan X. Effects of consideration of future consequences and temporal framing on acceptance of the HPV vaccine among young adults. Health Commun. 2016. September;31(9):1089–96. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2015.1038774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tversky A, Kahneman D. Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases. Science (80-). 1974;185(4157):1124–31. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4157.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Dyne EA, Henley SJ, Saraiya M, Thomas CC, Markowitz LE, Benard VB. Trends in human papillomavirus–associated cancers — United States, 1999–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:918–24. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6733a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niccolai LM, Pettigrew MM. The role of cognitive bias in suboptimal HPV vaccine uptake. Pediatrics. 2016;138(4):e20161537. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tversky A, Kahneman D. Evidential impact of base rates. Kahneman D, Slovic P, Tversky A, eds. Judgm Under Uncertain Heuristics Biases. 1981;(197):153–60. doi: 10.1002/car.2380010211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tversky A, Kahneman D. Extensional versus intuitive reasoning: the conjunction fallacy in probability judgment. Psychol Rev. 1983;90(4):293–315. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.90.4.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aczel B, Bago B, Szollosi A, Foldes A, Lukacs B. Measuring individual differences in decision biases: methodological considerations. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1770. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weber EU, Johnson EJ, Milch KF, Chang H, Brodscholl JC, Goldstein DG. Asymmetric discounting in intertemporal choice: A query-theory account: research article. Psychol Sci. 2007;18(6):516–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamoudi A, Thomas D. Do you care? Altruism and inter-generational exchanges in Mexico. Calif Cent Popul Res. 2006. [Accessed October25 2018]. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/03s0k54t. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howell JL, Shepperd JA. Establishing an information avoidance scale. Psychol Assess. 2016;28(12):1695–708. doi: 10.1037/pas0000315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Porter RM, Amin AB, Bednarczyk RA, Omer SB. Cancer-salient messaging for human papillomavirus vaccine uptake: A randomized controlled trial. Vaccine. 2018;36(18):2494–500. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jusot F, Khlat M. The role of time and risk preferences in smoking inequalities: a population-based study. Addict Behav. 2013. May;38(5):2167–73. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.12.011. Epub 2013 Jan 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ida T. A quasi-hyperbolic discounting approach to smoking behavior. Health Econ Rev. 2014;4:5. doi: 10.1186/s13561-014-0005-7. Published 2014 Jun 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gilkey MB, Magnus BE, Reiter PL, McRee A-L, Dempsey AF, Brewer NT. The vaccination confidence scale: a brief measure of parents’ vaccination beliefs. Vaccine. 2014;32(47):6259–65. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilkey MB, Reiter PL, Magnus BE, McRee A-L, Dempsey AF, Brewer NT. Validation of the vaccination confidence scale: a brief measure to identify parents at risk for refusing adolescent vaccines. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(1):42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Asch DA, Baron J, Hershey JC, Kunreuther H, Meszaros J, Ritov I, Spranca M. Omission bias and pertussis vaccination. Med Decis Mak. 1994;14(2):118–23. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9401400204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts JR, Thompson D, Rogacki B, Hale JJ, Jacobson RM, Opel DJ, Darden PM. Vaccine hesitancy among parents of adolescents and its association with vaccine uptake. Vaccine. 2015;33(14):1748–55. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.01.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brunson EK. The impact of social networks on parents’ vaccination decisions. Pediatrics. 2013;131(5):e1397–404. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- HPV and Cancer . National cancer institute; 2019. [accessed 2019 April19]. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/infectious-agents/hpv-and-cancer?redirect=true

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases Surveillance 2017 . Centers for disease control and prevention; 2018. [accessed 2019 April19]. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats17/other.htm