ABSTRACT

A 14-year-old girl presented with chronic headache, recurrent episodes of vomiting, fever, and two episodes of generalized tonic clonic seizure in the past 2 months. Neuroimaging revealed herniation of the brain along with the dura through a defect in the left greater wing of the sphenoid. Left pterional craniotomy was carried out. Herniation of the dural sac along with its contents through the bony defect in the greater sphenoid wing was identified lateral to the V2 nerve passing through the foramen rotundum. The dural defect was repaired. Bony defect was covered with a circular titanium plate. The patient did not have cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea postoperatively. At 6-month follow-up, she was asymptomatic.

KEYWORDS: Cerebrospinal fluid, rhinorrhea, sphenoid encephalocoele

INTRODUCTION

Sphenoidal encephalocoeles are defined as pathological herniations of dura and brain parenchyma through defect in the sphenoid bone. It is a rare condition, with reported overall incidence of approximately 1 in 35,000 people.[1] The natural history of meningoencephalocoeles and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks from the lateral recess is poorly understood, some attribute it to a congenitally patent lateral craniopharyngeal canal, which results from incomplete fusion of the greater sphenoid wing bone with the basisphenoid.[2]

We report an adolescent case of sphenoidal meningoencephalocele presenting with recurrent meningitis and fifth cranial nerve involvement.

CASE REPORT

A 14-year-old girl presented to the hospital with a history of chronic headache, recurrent episodes of vomiting, fever, and two episodes of generalized tonic clonic seizure in the past 2 months. A history of watery discharge from the left nostril was also present. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of brain revealed herniation of the brain along with the dura through a defect in the left greater wing of the sphenoid into the pterygopalatine fossa and retromaxillary space [Figures 1–3]. This mass contained tissue resembling extension of glial tissue of the temporal lobe into a cyst. There was no extension of this mass into the sphenoid sinus or sella. The patient had left hemiatrophy of the face, especially maxilla, and rest of the examination was normal. Computed tomography (CT) Brain & CT cisternography (Figures 3–5) revealed bony defect in the middle cranial fossa in the left greater wing of sphenoid with CSF leak.

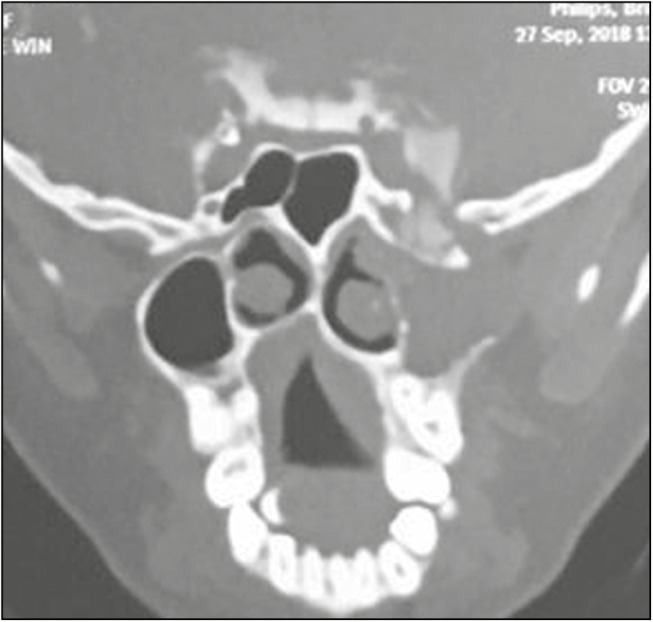

Figure 1.

CT scan coronal section shows defect in the left greater wing of the sphenoid into the pterygopalatine fossa and retromaxillary space

Figure 3.

Herniated glial tissue through the defect

Figure 5.

CT cisternography—leak noted through the defect in sphenoid bone and contrast seen filling the sac

Figure 2.

CT axial section shows defect in the left greater wing of the sphenoid

Figure 4.

3D reconstructed image showing the defect (white arrow)

Left pterional craniotomy was performed, followed by sphenoid ridge drilling and exposure of the cavernous sinus by dissecting the endosteal and the meningeal layer of the dura. Herniation of the dural sac along with its contents through the bony defect in the greater sphenoid wing was identified lateral to the V2 nerve passing through the foramen rotundum [Figure 6]. The herniated sac was opened, and the gliotic brain tissue was excised using suction and bipolar. The dural defect was repaired by placement of two facial grafts, one inside the dural defect and the second one overlaying the defect. Bony defect was covered with a circular titanium plate fixed to the base with 4mm screws [Figure 7]. Craniotomy flap was fixed with titanium plates and screws. The patient did not have CSF rhinorrhea postoperatively. At 6-month follow-up, she was asymptomatic.

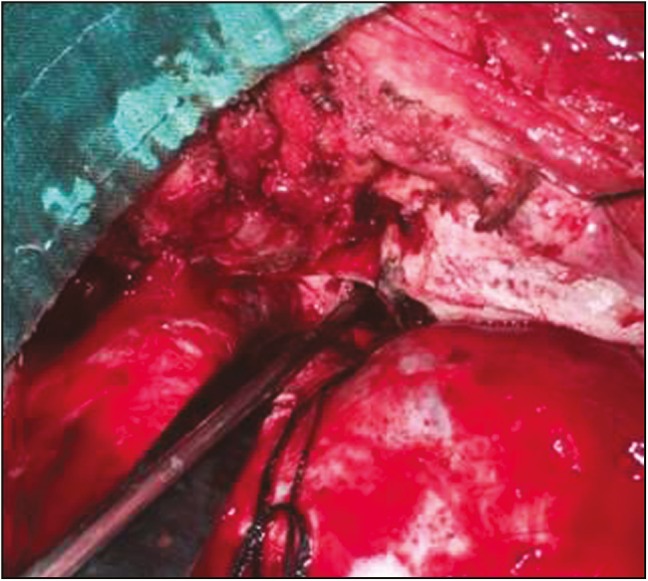

Figure 6.

Defect seen intraoperatively after reduction of herniated sac

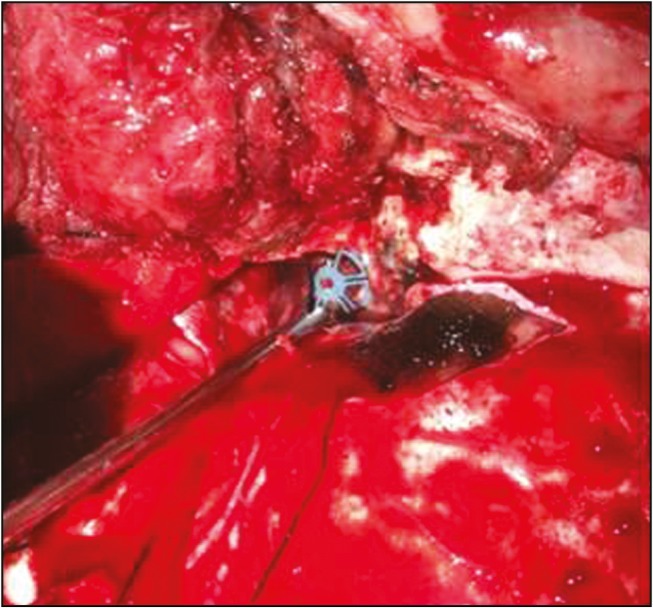

Figure 7.

Defect covered with titanium mesh

DISCUSSION

Encephalocoele occurs among one in every 3000–5000 live births.[3,4] Basal cephaloceles are less common with an estimated incidence of 1 in 35,000 live births. Basal encephalocoeles are classified into transethmoidal, spheno-orbital, sphenomaxillary, and transsphenoidal. A rare finding is a basal cephalocele that is limited to the sphenoid sinus.[5,6]

Sphenoid encephalocoele can be classified as: true transsphenoidal and true intrasphenoidal.[7] Lai et al.[1] classified them into a medial perisellar type and a lateral sphenoid recess type. Settecase et al.[8] classified spontaneous lateral sphenoid cephaloceles (SLSC) into two types, a type 1 SLSC, herniating into a pneumatized lateral recess of the sphenoid sinus, and a type 2 SLSC, isolated to the greater sphenoid wing without extension into the sphenoid sinus.

Lateral pneumatization of the sphenoid is observed in 25% patients, and has been postulated as a predisposing factor for lateral recess leaks.[9,10,11] Other hypothesis proposed that a “Sternberg canal”, which forms due to incomplete fusion of medial aspect of sphenoid bone can also act as a site of origin for congenital encephalocoele.[12]

Encephalocoeles, protruding into the infratemporal fossa or pterygopalatine fossa or toward the lateral wall of the nasopharynx, are commonly associated with deficits involving the horizontal portion of the greater sphenoidal wing, laterally to the cranial base foramina of the sphenoidal bone (foramen ovale and rotundum).[13,14] So the patient can present with different presentation according to the direction of dural sac and pressure symptoms on the neural structures.

Of the 26 patients studied by Settecase et al.,[8] 15 were type 1 SLSC, and 11 were type 2. One of the type 2 patients had CSF leak. Lai et al.[1] and Tabaee et al.[15] series had varied presentation of CSF rhinorrhea, meningitis, headache, and left temporal lobe abscess with seizures and fifth cranial nerve involvement.

The encephalocoele in our case was found to be compressing on the contents in foramen rotundum and ovale, probably leading to the underdevelopment of the structures served by them manifesting as hemiatrophy of the face.

CT cisternography, three-dimensional (3D) reconstructed multislice CT scan, and MRI provide excellent 3D definition of the lesion and the site of leak useful for both diagnosis and surgical planning.[16,17]

Surgical treatment is aimed at the prevention of leak and infections.[18] Transcranial approaches, usually a frontotemporal craniotomy, can give adequate access to the herniating sac. The repair of the defect can be achieved either extradurally or intradurally or combined.[19,20,21] Most often the herniated tissue is gliotic and nonfunctional, requiring excision. The osseous defect may be repaired using fat, local muscle, fascia, calvarial graft, and bone chips.[13,14,19] In our case, we used a titanium circular plate for covering the defect of sphenoid wing.

If the encephalocoele extends into the sphenoid sinus (type 1), endoscopic repair is preferred. Failure with the endoscopic approach may be related to inaccurate localization of the defect, insufficient graft size and its displacement, incomplete apposition of the graft to the skull base defect, and noncompliance of the patient with postoperative instructions.[22]

CONCLUSION

Sphenoid encephalocoele is one of the rare skull base encephalocoeles. It would be one of the differential diagnoses in cases of adolescents with spontaneous CSF leaks. Imaging and understanding of the anatomy and repairs usually have good outcomes.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lai SY, Kennedy DW, Bolger WE. Sphenoid encephaloceles: disease management and identification of lesions within the lateral recess of the sphenoid sinus. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1800–5. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200210000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Devi BI, Panigrahi MK, Shenoy S, Vajramani G, Das BS, Jayakumar PN. CSF rhinorrhoea from unusual site: report of two cases. Neurol India. 1999;47:152–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.David DJ, Proudman TW. Cephaloceles: classification, pathology, and management. World J Surg. 1989;13:349–57. doi: 10.1007/BF01660747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rathore YS, Gupta D, Mahapatra AK. Transsellar transsphenoidal encephalocele: a case report. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2010;46:472–4. doi: 10.1159/000325157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniilidis J, Vlachtsis K, Ferekidis E, Dimitriadis A. Intrasphenoidal encephalocele and spontaneous CSF rhinorrhoea. Rhinology. 1999;37:186–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLaurin RL. Encephalocele and related anomalies. In: Hoffman HJ, Epstein F, editors. Disorders of the developing nervous system: diagnosis and treatment. St Louis, MO: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1986. pp. 153–71. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abiko S, Aoki H, Fudaba H. Intrasphenoidal encephalocele: report of a case. Neurosurgery. 1988;22:933–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Settecase F, Harnsberger HR, Michel MA, Chapman P, Glastonbury CM. Spontaneous lateral sphenoid cephaloceles: anatomic factors contributing to pathogenesis and proposed classification. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2014;35: 784–9. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang J, Bidari S, Inoue K, Yang H, Rhoton A., Jr Extensions of the sphenoid sinus: a new classification. Neurosurgery. 2010;66:797–816. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000367619.24800.B1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bachmann-Harildstad G, Kloster R, Bajic R. Transpterygoid trans-sphenoid approach to the lateral extension of the sphenoid sinus to repair a spontaneous CSF leak. Skull Base. 2006;16:207–12. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-950389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schick B, Draf W, Kahle G, Weber R, Wallenfang T. Occult malformations of the skull base. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123:77–80. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1997.01900010087013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yücel A, Değirmenci B, Yilmaz MD, Altuntaş A. [Spontaneous trans-sphenoidal encephalocele presenting with nontraumatic cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea (case report)] Tani Girisim Radyol. 2004;10:196–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spacca B, Amasio ME, Giordano F, Mussa F, Busca G, Donati P, Genitori L. Surgical management of congenital median perisellar transsphenoidal encephaloceles with an extracranial approach: a series of 6 cases. Neurosurgery. 2009;65:1140–5. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000351780.23357.F5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landreneau FE, Mickey B, Coimbra C. Surgical treatment of cerebrospinal fluid fistulae involving lateral extension of the sphenoid sinus. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:1101–4. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199805000-00087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tabaee A, Anand VK, Cappabianca P, Stamm A, Esposito F, Schwartz TH. Endoscopic management of spontaneous meningoencephalocele of the lateral sphenoid sinus. J Neurosurg. 2010;112:1070–7. doi: 10.3171/2009.7.JNS0842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diebler C, Dulac O. Cephaloceles: clinical and neuroradiological appearance. Associated cerebral malformations. Neuroradiology. 1983;25:199–216. doi: 10.1007/BF00540233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blaivie C, Lequeux T, Kampouridis S, Louryan S, Saussez S. Congenital transsphenoidal meningocele: case report and review of the literature. Am J Otolaryngol. 2006;27:422–4. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arai A, Mizukawa K, Nishihara M, Fujita A, Hosoda K, Kohmura E. Spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea associated with a far lateral temporal encephalocele—case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2010;50:243–5. doi: 10.2176/nmc.50.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohkawa T, Nakao N, Uematsu Y, Itakura T. Temporal lobe encephalocele in the lateral recess of the sphenoid sinus presenting with intraventricular tension pneumocephalus. Skull Base. 2010;20:481–6. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1261261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tami TA. Surgical management of lesions of the sphenoid lateral recess. Am J Rhinol. 2006;20:412–6. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2006.20.2893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clyde BL, Stechison MT. Repair of temporosphenoidal encephalocele with a vascularized split calvarial cranioplasty: technical case report. Neurosurgery. 1995;36:202–6. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199501000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castelnuovo P, Dallan I, Battaglia P, Bignami M. Endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery: past, present and future. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;267:649–63. doi: 10.1007/s00405-009-1196-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]