Abstract

Introduction:

Men who have sex with men (MSM) are suboptimally engaged in efficacious HIV interventions, due in part to stigma.

Aim:

We sought to validate the Anal Health Stigma Model, developed based on theory and prior qualitative data, by testing the magnitude of associations between measures of anal sex stigma and engagement in HIV prevention practices, while adjusting for covariates.

Methods:

We conducted a cross-sectional online survey of 1,263 cisgender MSM living in the United States and analyzed data with structural equation modeling. We tested a direct path from Anal Sex Stigma to Engagement in HIV Prevention alongside 2 indirect paths, 1 through Anal Sex Concerns and another through Comfort Discussing Anal Sexuality with Health Workers. The model adjusted for Social Support, Everyday Discrimination, and Sociodemographics.

Main Outcome Measure:

Engagement in HIV Prevention comprised an ad hoc measure of (i) lifetime exposure to a behavioral intervention, (ii) current adherence to biomedical intervention, and (iii) consistent use of a prevention strategy during recent penile-anal intercourse.

Results:

In the final model, anal sex stigma was associated with less engagement (β = −0.22, P < .001), mediated by participants' comfort talking about anal sex practices with health workers (β = −0.52; β = 0.44; both P < .001), adjusting for covariates (R2 = 67%; χ2/df = 2.98, root mean square error of approximation = 0.040, comparative fit index = 0.99 and Tucker-Lewis index = 0.99). Sex-related concerns partially mediated the association between stigma and comfort (β = 0.55; β = 0.14, both P < .001). Modification indices also supported total effects of social support on increased comfort discussing anal sex (β = 0.35, P < .001) and, to a lesser degree, on decreased sex-related concerns (β = −0.10; P < .001).

Clinical Implications:

Higher stigma toward anal sexuality is associated with less engagement in HIV prevention, largely due to discomfort discussing anal sex practices with health workers.

Strength & Limitations:

Adjustment for mediation in a cross-sectional design cannot establish temporal causality. Self-report is vulnerable to social desirability and recall bias. Online samples may not represent cisgender MSM in general. However, findings place HIV- and health-related behaviors within a social and relational context and may suggest points for intervention in health-care settings.

Conclusion:

Providers' willingness to engage in discussion about anal sexuality, for example, by responding to questions related to sexual well-being, may function as social support and thereby bolster comfort and improve engagement in HIV prevention.

Keywords: Stigma, Anal Sexuality, Anal Sex Stigma, Men Who Have Sex With Men, HIV/AIDS, Sexual Stigma, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

INTRODUCTION

The pandemic involving the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has disproportionately burdened gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM).1 In the United States, there is an increasing incidence of HIV among specific subpopulations each year, despite some stabilization.2-4 This pattern occurs alongside the advancement of behavioral and biomedical interventions5-7 that, in combination, could avert a significant number of new infections.8 However, despite promising trends,2 engagement of MSM in HIV prevention simply has not occurred at the necessary pace to curb the epidemic across the United States4—a particularly urgent problem to prioritize, given the federal goal to end the epidemic within the next 10 years.9 Few HIV-negative or HIV-status unknown MSM report participation in behavioral interventions,10-12 and condom use has decreased in recent years. 13 Use of biomedical interventions such as pre-exposure and postexposure prophylaxis (PrEP and PEP) also remains low.12,14 5 years after the Food and Drug Administration approval, 35% of MSM reported PrEP use,15 but retention in PrEP-specific health care continued to be suboptimal.16 Among MSM living with HIV, surveillance data suggest a similar retention problem across the HIV care continuum,17-19 compromising the potential for community-level viral suppression.20

Leveraging behavioral and biomedical interventions to end the epidemic9 will require identifying mechanisms that limit involvement of those MSM least likely to engage in HIV prevention. Stigma, the social and structural labeling of differences that empowers the stereotyping, separation, loss of status, and discrimination of those labeled,21 is a major barrier in the prevention and control of HIV globally across all populations.22,23 For MSM, social and structural barriers related to sex and sexuality (ie, sexual stigmas)24,25 are potential candidates for intervention to improve engagement, as they intersect across stigmas among MSM, including devaluation by racial group, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, HIV status, and other labels.1,26 Left unaddressed, sexual stigma particularly impedes MSM engagement in HIV prevention and treatment.27-31 Fortunately, sexual stigma is also amenable to modification.32,33

An important and rarely studied aspect of sexual stigma is stigma toward anal sexuality.34 Anal sex is the primary route of HIV transmission among MSM, but the influence of any associated stigma on MSM engagement in HIV prevention practices is fairly uncharted. Limited evidence, largely qualitative, suggests that anal sex may function as a label for social devaluation among some MSM35-37 and that experiences related to stigma, including the absence of information about anal sexuality, likely influence both men's HIV-relevant decision-making during sex and their health-seeking behavior in health-care settings.38,39 To date, however, studies have yet to quantify potential associations between exposure to anal sex stigma and MSM engagement in HIV prevention practices.

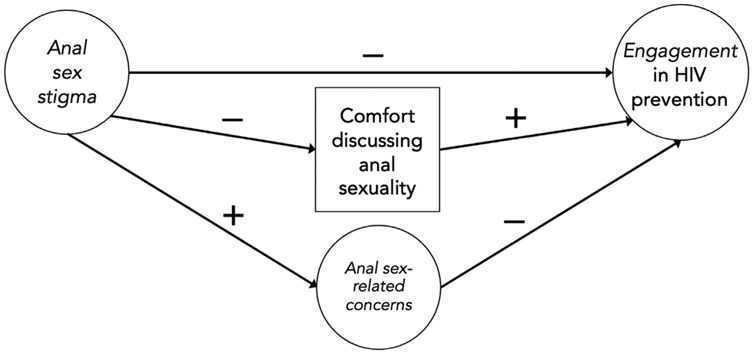

To better understand the potential role of stigma specifically toward anal sex, we developed an Anal Health Stigma Model (Figure 1) based on the theories of concealable stigmatized identities,40 sexual stigma,24 fundamental causes of disease,41 and our own qualitative work.34 Our qualitative work found that MSM harbor anal sex–related concerns and anxieties, often posed as questions about anal physiology and sexual functioning, connected to the absence of sexual education.34 These concerns are likely related to HIV risk and concealment. For example, interest in hygiene, pain reduction, and pleasure motivate the use of douches,42,43 substances,44-47 and lubricants,48,49 which can potentially exacerbate HIV risk,50-52 but which, similar to sexual behavior in general, MSM rarely discuss with sex partners or in health-care settings.34 Therefore, we hypothesize that stigma toward anal sexuality contributes to elevated sex-related concerns along with compromised comfort discussing anal sex, a precursor to concealment. These mediators, as well as stigma, likely contribute to behavioral health responses among MSM that impede both their health-seeking engagement in sexual risk reduction and in HIV prevention and care services.

Figure 1.

Anal Health Stigma Model positing direct effects of high anal sex stigma linked to less engagement, mediated through elevated anal sex–related concerns, and lessened comfort discussing anal sexuality. A circle denotes a latent factor; a square denotes a manifest (observed) variable per.104

To study these determinants, we surveyed a national, ethnically and racially diverse sample of cisgender MSM. We conducted structural equation modeling (SEM) to identify whether anal sex stigma does indeed impede HIV prevention practices through our proposed mediators.

METHODS

Following upon a qualitative study,34 we developed a set of scales and an inventory of sex-related questions and concerns, which we subsequently pilot tested and evaluated for scale performance,105 then used in model testing among 1,263 sexually active cisgender MSM. The ethical review boards at both the University of Washington and New York State Psychiatric Institute approved the research.

Sample

Recruitment relied on snowball and targeted sampling, including paid and donated advertisements on social media and men-seeking-men platforms. We also sent electronic announcements to affinity groups, with at least 1 in each state or territory dedicated to serving people of color. Images for announcements reflected racial and ethnic diversity.

Eligibility criteria required reporting as a cisgender man (using a 2-step method53), with at least 1 male anal sex partner in the past year; living in the United States; speaking, reading, and writing English; and being 18 years of age or older. We defined “anal sex” broadly, including penile, oral, and manual stimulation. Screening, consent, and surveys were hosted through an online platform.54 We redirected non-Latino white MSM away from the survey after this group comprised a quota of more than one-third of the targeted sample size, to ensure sufficient racial and ethnic diversity.

Of the 1,936 respondents who responded beyond the information statement, 549 (28%) partially completed the survey, and 1,387 (72%) completed the survey. Among these 1,387 completers, 1,263 (91%) reported penile-anal intercourse with a male partner in the past 3 months, forming our analytic sample. Their median completion time was 27 minutes (interquartile range: 18 minutes).

Procedures

On the 1st survey screen, participants could opt into viewing sexually explicit cartoon images which were featured intermittently to encourage retention and attention.55,56 We randomized items within measures to lessen response bias from a fixed order. Respondents who completed the survey could voluntarily choose to enter a raffle to win 1 of 12 $50 gift certificates. We collected responses over 10 weeks, between July and September 2017.

To flag potential fraudulent responses, we checked repetition across key variables, including eligibility criteria, age, zip code, start/stop times, and internet protocol and email addresses, when available.57 We further examined responses that indicated: a non-U.S. location; a previously excluded respondent who ended participation within the prior 2 hours; straight-line responding; completion times less than one-third of the median survey length; and final survey answers that misaligned with related earlier questions. This process excluded 17 respondents from inclusion in our sample of 1,263, or 1.3%.

Measures

Primary Explanatory Variable

Anal Sex Stigma.

We developed a 17-item measure of stigma toward anal sexuality, the Anal Sex Stigma Scales (ASS-S, α = 0.81), based on earlier qualitative and quantitative studies,33,52 then validated the measure with the 1,387 respondents of the present study who completed measures, regardless of their recent sexual activity or positional preferences during intercourse.105 Among the 1,263-person analytic sample, 1 subscale comprised self-stigma (α = 0.72; eg, “I may never let go of the shame I feel about anal sex”), and 2 other subscales comprised a combination of experienced and anticipated stigma in the forms of omission stigma (α = 0.73; eg, “Most guys don't understand how to ease into anal sex”) and provider stigma (α = 0.80; eg, “Health workers would treat me badly if they knew the ways I have anal sex”). Likert response categories ranged from 0 (disagree strongly) to 3 (agree strongly).

Proposed Mediators

Anal Sex–Related Concerns.

In our earlier formative work, we validated an index of 45 frequently asked questions about anal sexuality, the Anal Sex Questions Index (ASQx), derived from 35 in-depth interviews with key informants and MSM participants, pilot tested among 218 MSM online, and validated among the present study's larger sample.105 We selected the 10 least skewed items with the highest variability in our sample of sexually active MSM, which collectively indicated a measure of worry or concern (α = 0.89; eg, “Why does anal sex feel different for me than it used to feel?” “How many other guys have problems with anal sex like the problems I have?”). Respondents rated their interest in hearing an answer to each question, from 0 (not at all) to 3 (very interested).

Comfort Discussing Anal Sex and Sexual Orientation.

1 item measured respondent comfort talking with medical providers about their specific anal sex practices,57 with Likert response categories ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely comfortable). We also developed a parallel item for comfort discussing attraction to men.

Primary Dependent Variable

Engagement in HIV Prevention Practices.

We operationalized engagement as a latent construct in SEM, based on 3 dichotomous variables (Figure 2): (i) behavioral intervention, (ii) biomedical intervention, and (iii) prevention strategy during recent penile-anal intercourse (standardized Cronbach's α = 0.54).

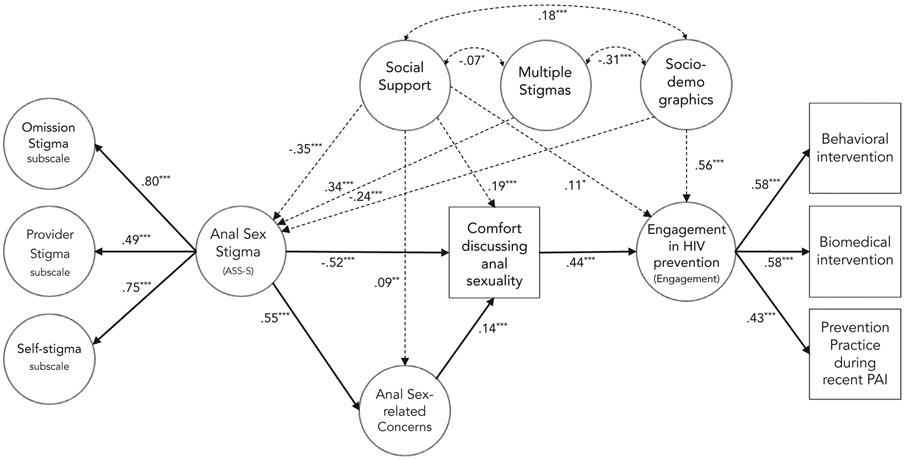

Figure 2.

Final model showing only significant paths with standardized beta coefficients, adjusting for covariates in dotted lines, *P <.05; **P <.01; ***P <.001. A circle denotes a latent factor; a square denotes a manifest (observed) variable per.104 Anal Sex Stigma comprises 3 latent subscales (self-stigma, provider stigma, and omission stigma). Engagement comprises 3 observed dichotomous variables (behavioral intervention, biomedical intervention, prevention practice during recent PAI). PAI refers to penile-anal intercourse.

Behavioral Intervention.

Those who reported ever participating in a one-to-one or small group conversation with a health worker about HIV prevention practices, as operationalized by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,58 were coded as having engaged in a behavioral intervention.

Biomedical Intervention.

We followed conventions for engagement in HIV treatment for people living with HIV,19 HIV testing recommendations for MSM,59 treatment guidelines for sexually transmitted infection,60 and protocols for PrEP.61 To be considered not engaged in biomedical intervention, seropositive respondents needed to report one of the following: most recent medical visit > 6 months ago, > 2 missed antiretroviral therapy (ART) doses in the past week, or detectable viral load. For seronegative respondents, those who reported no HIV test result within the past 2 years or current PrEP use but no HIV test in the past 3 months were coded as not engaged in biomedical intervention. Finally, respondents of any serostatus who suspected an incident sexually transmitted infection in the past 3 months but who did not go to a health-care provider, or who were never tested for HIV or never received an HIV test result, were coded as not engaged in biomedical intervention.

Prevention Strategy During Penile-Anal Intercourse.

We developed a dichotomous variable for prevention strategy based on the protective benefits of condom use,62 adherence to antiretroviral medication as either treatment or PrEP,5,7,61 and harm reduction strategies that MSM use to minimize HIV risk.63,64 We coded men as engaged in a prevention strategy during recent penile-anal intercourse who met any of the following conditions: (i) consistent (100%) use of condoms; (ii) consistent use of ART or PrEP (ie, undetectable viral load if seropositive, and ≤ 2 missed doses of ART or PrEP in the past week regardless of serostatus); or (iii) condomless intercourse with only one partner in the past year whom the respondent had not recently met, who had no concurrent sexual partnerships in the past 3 months, and who was either seroconcordant or adhering to ART or PrEP protocols.

Covariates

In interviews that informed the development of the ASS-S, respondents described an amalgamation of anal sex stigma and sexual racism,105 an intersection of multiple targets of devaluation65 with relevance to sexual behavior and health-seeking behavior.66,67 Social support may also play a role as a buffer against stigma and attendant urges to conceal sexuality and as encouragement for health-seeking behavior.68,69 Our model therefore adjusts for exposure to these constructs and tests for additional sociodemographic confounds of the association between anal sex stigma and HIV prevention.

Social Support.

We adapted the 8-item emotional and informational subscale of the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Scale70 to be specific to anal sexuality, which yielded high reliability in our sample (α = 0.97). Participants endorsed the availability of support (eg, “Someone to share my most private worries and fears with about anal sex” and “Someone who's advice about anal sex I really want”) with Likert response categories ranging from 1 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time).

Everyday Discrimination.

The 5-item Everyday Discrimination Scale71 measured perceived frequency of discrimination (α = 0.87; eg, “You are treated with less respect than others”) based on a range of potential stigmatized identities, including racial and ethnic identity, with Likert response categories ranging from 0 (never) to 5 (almost every day).

Analytic Plan

SEM analyses were conducted using Mplus. We followed a common 2-step procedure: 1st, confirmatory factor analysis to assess the fit of the measurement model and then path analysis with model specification.72 Given the number of ordinal variables in our model, we chose a weighted least squares multivariate estimator using a diagonal weight matrix, with theta parameterization, with theta parameterization. To assess model goodness of fit, we examined the comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), using their widely accepted cutoff scores (CFI and TLI > 0.9; and RMSEA < 0.05).73,74 We also examined the ratio of the chi-square to degrees of freedom (χ2/df), as a guide toward increasing fit in successive models, with a target between 2 and 3, as long as all other fit indices were favorable.73,75 To examine sources of substantial model misfit, we requested modification indices > 50 to assess options to increase model fit that might be congruent with theory. To select measures for inclusion as covariates in model testing, we examined bivariate statistics, using Spearman's rho (rs), point biserial correlations for dichotomous components of engagement, and chi-square and t-test analyses. We used the joint significance test, where both paths have to be significant, to conclude mediation. Literature supports that joint significance is almost as powerful as bootstrapping without the computational demands and potential for alpha inflation.76

Mplus conducts full information maximum likelihood estimation by default,77 thereby including participants with missing endogenous items. We conducted Little's Missing Completely at Random test,78 and the results were significant (χ2 = 833.53(662), P = .000), indicating that data were not missing completely at random. However, missing data were minimal, less than 0.3% at the item level across respondents.

RESULTS

Sample and Descriptive Findings

The sample reflected a broad distribution across ages, incomes, racial/ethnic group identification, and geographic distribution (see Table 1). Most reported a frequency of engaging in anal sex between twice a week to monthly. The top quartile reported more than 13 anal sex partners in the past year, and most expressed a preference for versatile sexual positioning, with exclusively insertive anal intercourse least preferred. Most men reported that their last HIV test was seronegative, and more than one-third of these men reported currently using PrEP. The vast majority of respondents living with HIV reported engagement with health care and had achieved viral suppression. Most samples reported past engagement in a behavioral intervention, with slightly more currently engaged in biomedical intervention, and fewer engaged in an HIV prevention strategy during recent penile-anal intercourse.

Table 1.

Characteristics for cisgender MSM reporting recent penile-anal intercourse (N = 1,263)

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age in years (M, SD) | 36.1 (11.0) |

| Geography | |

| Rural | 93 (7.4) |

| Small | 145 (11.5) |

| Medium-sized | 279 (22.1) |

| Large | 586 (46.4) |

| Suburb | 160 (2.7) |

| Region | |

| Northeast | 278 (22.0) |

| Midwest | 224 (17.7) |

| South | 520 (41.2) |

| West | 240 (19.0) |

| Race and ethnicity | |

| Latino, Hispanic, or Spanish ethnicity (of any race) | 270 (21.4) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native (AIAN) | 17 (1.3) |

| Asian or Asian American | 78 (6.2) |

| Black or African American | 204 (16.2) |

| White or Caucasian (non-Latino) | 673 (53.3) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (NHPI) | 4 (0.3) |

| Biracial or multiracial | 80 (6.3) |

| Education | |

| ≤ High school/GED | 99 (7.8) |

| Some college | 289 (22.9) |

| 2-year college | 73 (5.8) |

| 4-year college | 415 (32.9) |

| Masters | 266 (21.1) |

| Doctoral/professional | 121 (9.6) |

| Income | |

| Less than $15,000 | 159 (12.6) |

| $15,000–$29,999 | 217 (17.2) |

| $30,000–$44,999 | 208 (16.5) |

| $45,000–$59,999 | 175 (13.9) |

| $60,000–$74,999 | 132 (10.5) |

| $75,000–$89,999 | 92 (7.3) |

| $90,000 or more | 270 (21.4) |

| Housing | |

| Shelter/dorm/drug treatment/other | 21 (1.7) |

| Someone else's home | 157 (12.4) |

| Rent | 717 (56.8) |

| Own | 368 (29.1) |

| Relationship status* | |

| Single | 607 (48.1) |

| Casually dating several people | 91 (7.2) |

| Boyfriend or girlfriend | 146 (11.6) |

| Partner or lover | 207 (16.4) |

| Legal, civil, committed partnership | 202 (16.0) |

| Open relationship or not sure if open | 410 (32.5) |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Gay | 1,022 (80.9) |

| Bisexual/heterosexual | 120 (9.5) |

| Queer | 62 (4.9) |

| No label | 45 (3.6) |

| Additional/2 spirit | 14 (1.1) |

| Sexual position preference | |

| “Bottoming” (receptive) | 391 (31.0) |

| “Topping” (insertive) | 282 (22.3) |

| “Versatile” (both receptive and insertive) | 550 (43.5) |

| No preference/not sure | 40 (3.2) |

| Outness about sexual attraction to men | |

| Nobody | 32 (2.5) |

| Select friends | 161 (12.7) |

| All friends and select family | 213 (16.9) |

| All friends and all family | 94 (7.4) |

| Almost everyone (friends, family, coworkers, and so on) | 763 (60.4) |

| Never tested/never received HIV result | 71 (5.6) |

| HIV seronegative | 999 (79.1) |

| Tested within the last year | 887 (88.8) |

| Current PrEP use | 350 (35.0) |

| HIV seropositive | 183 (14.5) |

| Diagnosed within past 2 years | 23 (12.6) |

| Linked to care at time of diagnosis | 170 (92.9) |

| Retained in care (most recent visit < 6 mos ago) | 175 (95.6) |

| Prescribed ART | 178 (97.3) |

| Undetectable viral load | 167 (91.3) |

| Health-care engagement | |

| No health insurance or primary care provider (PCP) | 90 (7.1) |

| Out to PCP about anal sex with men (among 1,092 with PCP) | 811 (74.3) |

| Behavioral HIV intervention | 942 (74.6) |

| Thought you had an STI but did not see medical provider | 118 (9.3) |

| Sexual Behavior | |

| 13 or more anal sex partners in past year† | 325 (25.7) |

| Receptive penile-anal intercourse in past 3 months | 1,019 (80.7) |

| Insertive penile-anal intercourse in past 3 months | 963 (76.2) |

| HIV-related Sexual Behavior in past 3 months | |

| Any condomless receptive anal intercourse | 824 (80.9) |

| Any condomless insertive anal intercourse | 789 (82.0) |

| Chemoprophylaxis (PrEP/ART) | 470 (37.2) |

| Any HIV prevention strategy during anal intercourse | 805 (63.7) |

ART = antiretroviral therapy; GED = General Education Diploma; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; M = mean; PrEP = pre-exposure prophylaxis; STI = sexually transmitted infection.

N = 1,253 due to missingness.

“How many people have you had anal sex within the past year? (Anal sex here includes any sexual contact with the ass, like touching, licking or penetration.)”

Overall, participants reported a low level of anal sex stigma (mean [M] = 1.04, SD = 0.50), approximately one-third of the possible 0 to 3 range, with higher levels of omission stigma (M = 1.60, SD = 0.28) than provider stigma (M = 0.94, SD = 0.12) and self-stigma (M = 0.56, SD = 0.21). Participants harbored moderate sex-related concerns (M = 1.72, SD = 0.14), about 57% of the possible 0 to 3 range. Social support specific to anal sexuality was also low to moderate (M = 2.00, SD = 0.13); on average, support was available “a little of the time.” They reported moderate comfort discussing anal sex and attraction to men, with much higher variability than for the other measures (M = 2.10, SD = 1.39 and M = 2.73, SD = 1.31, respectively).

Bivariate Analyses

We detected significant differences in how respondents ranked each of the 2 comfort with discussion items (Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test, Z = −20.5, P < .0001). Overall, nearly half (47.4%) felt more comfortable discussing attraction to men than anal sex practices, 2.8% reported the inverse, and 49.7% reported the same comfort level regardless of the topic. We therefore opted to use the single item related to anal sexuality in our model.

Bivariate analyses with sociodemographic variables indicated that greater age, higher household income, higher education, greater outness about attraction to men, medical coverage, and racial group identification other than black/African-American were each negatively associated with stigma and positively associated with engagement (all P < .05). We therefore constructed a formative latent factor for sociodemographics, comprising these 6 variables, to adjust for potential confounding while accounting for intercorrelation and measurement error. As a linear composite of these risk factors, higher values indicate better outcomes.

Measurement Model

Our measurement model comprised 6 latent factors, including our primary variables and our 3 covariates, and converged normally with acceptable fit: χ2(1,109) = 3324.33, P < .0001, χ2/df = 3.00, RMSEA = 0.040 (95% CI: 0.038–0.041), probability of RMSEA < 0.05 = 1.00, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99. Standardized factor loadings (λ) on engagement were all significant (P < .001): behavioral intervention (λ = 0.58), biomedical intervention (λ = 0.58), and prevention strategy during recent penile-anal intercourse (λ = 0.43). Table 2 details means, standard deviations, correlations, and covariances among study variables.

Table 2.

Loadings, means, standard deviations, reliability, correlations, and covariances among all variables (N = 1,263)

| Variable | λ† | M (SD) | α (95% CI) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anal Sex Stigma Scales | 1.04 (0.50) | 0.81 (0.80–0.83) | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | Omission | 0.80 | 1.60 (0.28) | 0.73 (0.70–0.75) | – | 0.61 | 0.65 | 0.33 | −0.29 | −0.87 | 0.36 | −0.08 | −0.10 | −0.14 | −0.14 | −0.13 | −0.25 | −0.17 | −0.16 | −0.10 |

| 2 | Self-stigma | 0.75 | 0.56 (0.21) | 0.72 (0.69–0.74) | 0.53*** | – | 0.66 | 0.55 | −0.59 | −1.26 | 0.60 | −0.23 | −0.24 | −0.17 | −0.30 | −0.30 | −0.46 | −0.34 | −0.43 | −0.20 |

| 3 | Provider-stigma | 0.49 | .94 (0.12) | 0.80 (0.78–0.81) | 0.50*** | 0.32*** | – | 0.31 | −0.53 | −0.63 | 0.70 | −0.02 | 0.20 | −0.02 | −0.10 | −0.01 | −0.04 | −0.11 | −0.25 | −0.23 |

| 4 | Anal sex concerns | 1.72 (0.14) | 0.89 (0.88–0.90) | 0.41*** | 0.41*** | 0.21*** | – | −0.14 | −0.37 | 0.29 | −0.06 | −0.19 | −0.11 | −0.17 | −0.15 | −0.20 | −0.11 | −0.13 | −0.04 | |

| 5 | Comfort discussing anal sex | 2.10 (1.40) | −0.34*** | −0.44*** | −0.35*** | −0.15*** | – | 1.09 | −0.22 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.38 | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.23 | ||

| 6 | Social support | 2.00 (0.13) | 0.97 (0.97–0.98) | −0.36*** | −0.32*** | −0.14*** | −0.13*** | 0.38*** | – | −0.29 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.24 | 0.30 | 0.33 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.53 | −0.50 | |

| 7 | Multiple stigmas | 1.61 (1.10) | 0.87 (0.86–0.88) | 0.31*** | 0.33*** | 0.34*** | 0.22*** | −0.16*** | −0.07* | – | −0.42 | −0.01 | −0.21 | −0.36 | −0.30 | 0.01 | −0.04 | −0.26 | −0.13 | |

| Sociodemographics | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | Age | 0.51 | −0.09** | −0.17*** | −0.01 | −0.06 | 0.10** | 0.01 | −0.31*** | – | 0.07 | 0.24 | 0.53 | 0.30 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.28 | ||

| 9 | Race | 0.34 | −0.12** | −0.17** | 0.13** | −0.20*** | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.07 | – | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.41 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.03 | ||

| 10 | Education | 0.52 | −0.17*** | −0.13*** | −0.02 | −0.11*** | 0.06* | 0.08** | −0.16*** | 0.24*** | 0.25*** | – | 0.48 | 0.44 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.19 | ||

| 11 | Income | 0.74 | −0.17*** | −0.22*** | −0.07* | −0.18*** | 0.12*** | 0.11*** | −0.27*** | 0.53*** | 0.21*** | 0.48*** | – | 0.41 | 0.24 | 0.18 | 0.25 | 0.20 | ||

| 12 | Medical coverage | 0.57 | −0.15** | −0.22** | −0.01 | −0.15** | 0.08 | 0.11* | −0.22*** | 0.30*** | 0.05 | 0.41*** | 0.44*** | – | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.28 | ||

| 13 | Outness | 0.60 | −0.30*** | −0.34*** | −0.03 | −0.21*** | 0.38** | 0.25*** | 0.01 | 0.08* | 0.41*** | 0.21*** | 0.24*** | 0.11 | – | 0.35 | 0.25 | 0.27 | ||

| Engagement | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | Behavioral intervention | 0.58 | −0.20*** | −0.25*** | −0.07 | −0.12** | 0.35*** | 0.26*** | −0.03 | 0.19*** | 0.13** | 0.20*** | 0.18*** | 0.14* | 0.35*** | – | 0.33 | 0.24 | ||

| 15 | Biomedical intervention | 0.58 | −0.19*** | −0.32*** | −0.16*** | −0.14** | 0.37*** | 0.18*** | −0.19*** | 0.18*** | 0.15** | 0.16*** | 0.25*** | 0.10 | 0.25*** | 0.33*** | – | 0.27 | ||

| 16 | Prevention during PAI† | 0.43 | −0.11** | −0.15*** | −0.15*** | −0.05 | 0.23*** | −0.17*** | −0.09* | 0.18*** | 0.03 | 0.19*** | 0.20*** | 0.28*** | 0.27*** | 0.24*** | 0.27*** | – |

Covariances are in bold; correlations are below the diagonal

P < .05

P < .01

P < .001 (all 2-tailed).

PAI = penile-anal intercourse.

Factor loadings are all significant (P < .001)

Anal Health Stigma Model

The structural paths hypothesized in our conceptual model (Figure 1), adjusting for covariates, provided good fit for the data: χ2(1,159) = 3575.66, P < .0001, χ2/df = 3.09; RMSEA = 0.041 (95% CI: 0.039–0.042), probability of RMSEA < 0.05 = 1.00, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99. However, modification indices (ranging from 57 to 195) suggested additional and theoretically congruent associations. Their inclusion in the final model (Figure 2, showing only significant paths) improved fit (χ2(3) = 48.18, P < .0001) and indicated good fit: χ2(1,156) = 3449.72, P < .0001, χ2/df = 2.98; RMSEA = 0.040 (95% CI: 0.038–0.041), probability of RMSEA < 0.05 = 1.00, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99. This final model accounted for 67% of the variance in engagement, 39% in anal sex stigma, and 27% in anal sex concerns (all P < .001).

As seen in Table 3, the direct effect of stigma on engagement was not statistically significant, but total effects indicate that higher stigma was linked to less engagement (β = −0.22, P < .001). This association was mediated (see Figure 2) by comfort discussing anal sexuality, with higher stigma linked to less comfort (β = −0.52) and more comfort linked to more engagement (β = 0.44; both P < .001).

Table 3.

Standardized β from structural equation modeling to test direct, indirect and total effects of Anal Sex Stigmas on Engagement in HIV Prevention among cisgender MSM who reported anal sex in the preceding year (N = 1,263)

| Explanatory variables | Covariates adjusted for confounding | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | Anal sex stigmas | Anal sex concerns | Comfort discussing anal sex with health workers |

Social support specific to anal sex |

Everyday discrimination |

Sociodemographics | |

| Direct effects | Anal sex stigmas | – | −0.35* | 0.34* | −0.24† | ||

| Anal sex concerns | 0.55* | – | 0.09† | ||||

| Comfort discussing | −0.52* | 0.15* | – | 0.19* | |||

| Engagement | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.44* | 0.11‡ | 0.09 | 0.56* | |

| Indirect effects | Anal sex stigmas | – | |||||

| Anal sex concerns | – | −0.19* | −0.13* | ||||

| Comfort discussing | 0.08† | – | 0.17* | 0.10* | |||

| Engagement | −0.23* | 0.06† | 0.16* | −0.08† | 0.05‡ | ||

| Total effects | Anal sex stigmas | – | −0.35* | 0.34* | −0.24* | ||

| Anal sex concerns | 0.55* | – | −0.10† | −0.13* | |||

| Comfort discussing | −0.44* | 0.15* | – | 0.35* | 0.10* | ||

| Engagement | −0.22* | 0.05 | 0.44* | 0.28* | 0.02 | 0.61* | |

R2 in Engagement = 0.67%; RMSEA = 0.040 (95% CI: 0.038–0.041, probability of RMSEA < 0.05 = 1.00); CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.99. HIV = human immunodeficiency virus.

P < .001

P < .01

P < .05

Model testing did not support mediation from stigma to sex-related concerns (β = 0.55, P < .001) and then to engagement (β = −0.01, P = .90), nor a total effect of these concerns on engagement (β = 0.06, P = .35). However, the final model supported a mediation effect of stigma on comfort through elevated concerns: higher stigma was linked to elevated concerns (β = 0.55, P < .001), and elevated concerns were weakly but significantly associated with greater comfort (β = 0.15, P < .01).

Notably, higher informational and emotional social support specific to anal sexuality was linked to lower levels of stigma (β = −0.35, P < .001), greater comfort (β = 0.35, P < .001) and lower concerns (β = −0.10, P < .01), in addition to greater engagement (β = 0.28, P < .001).

DISCUSSION

In our sample, MSM who endorsed less anal sex stigma also reported important HIV-related protective behaviors, including greater comfort talking with health workers about their specific anal sex practices and greater engagement in HIV services and sexual risk reduction. The overall association between stigma and engagement was low, but these other relationships had medium to strong effect sizes, even with adjustment for social support, other forms of discrimination, and confounding sociodemographic factors (ie, age, outness, racial group, education, income and medical coverage). We found no evidence of mediation by elevated interest in anal sex–related questions, our measure of concern, despite a strong negative association with stigma. However, the model also indicated that social support specific to anal sex was significantly and strongly associated with less stigma and more comfort, and with greater engagement.

The finding that discomfort with discussion mediates the relation between stigma and health is consistent with our formative qualitative work34 and literature on sexual stigma.79 MSM may have strong reasons to conceal their participation in anal sex in particular. For example, heterosexuals report less willingness to attend a dinner event with a fictionalized gay man who has been characterized as “versatile” as compared with when his involvement in anal sex is disclosed but not specified positionally.35 As we heard in earlier qualitative interviews during our formative research, this may contribute to men's aversion to discussing specific anal sex practices, whether with friends, family, and sex partners, or in health-care settings.34 We detected this aversion to discussing anal sexuality in our current sample, with significantly greater comfort discussing attraction to men than specific anal sex practices. This suggests that discussing anal sex functions somewhat differently than discussing sexual orientation and is a reminder that the more HIV-specific topic of anal sexuality may be more difficult to broach and target for intervention.

Avoiding the subject of anal sexuality in health-care may therefore be common among MSM, as protection against the deleterious effects of stigma on health and social wellbeing. In our sample, of those with a primary medical provider, 75% reported being “out” about anal sex with men to their provider, which is higher than the 68% reported in the 2008 National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System80 and somewhat consistent with other studies documenting outness about sexual orientation. We know that difficulty disclosing MSM status is associated with both poor health-care access82 and less receipt of MSM-specific recommended screenings,83 similar to our study. This pattern suggests that many MSM may be underidentified for continued intervention and that their urges to conceal, albeit protective to some extent,84,85 also compromise their access to health care and the biomedical and behavioral interventions that could curb the HIV epidemic.79,80 Our findings add that concealment among MSM is not purely about sexual orientation or general sexual attraction but includes specific reticence to discuss anal sex, the behavior most associated with their disproportionate burden of HIV.

The effects of social support in our sample are particularly compelling in light of the need for novel interventions that encourage disclosure and promote engagement. Our social support measure is an adaptation of the emotional and informational support subscale of the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Scale, specifying anal sex within each item. Although our measure of interest in answers to questions about anal sex was not significantly associated with poor engagement, responding to MSM-specific anal sex interests, whether in health care or other relationships, might function as emotional and informational support. Our model testing suggests that this, in turn, could increase comfort with discussion about specific anal sex practices. One novel opportunity may be to respond to specific questions MSM harbor about anal sex, as a possible path to improve engagement in HIV services and sexual prevention practices. In pilot testing in a high-stigma context, this sort of sex-positive approach to mitigating stigma, focused on client questions about anal pleasure and health, has demonstrated high acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness among health workers.86

While we found evidence of a negative association of anal sex stigma with engagement in HIV prevention, it is important to note that intersecting forms of devaluation operate on health-related behavior.87,88 Attention to the intersection of anal sex stigma with other stigmas may inform ideas about how to inoculate the effects of multiple stigmas, particularly given the presence of effects in our study even after adjusting for confounding by other forms of everyday discrimination. One potential option might be to intervene across the diversity of people who engage in anal sex, rather than commit further to stereotypes that equate anal sex with male homosexuality.34 Indeed, the Anal Health Stigma Model is broadly applicable to additional populations that engage in anal sex.89-94 The extent to which stigma among these populations too is associated with poor engagement would be important to quantify.95

Our study has several limitations. We should be cautious to advocate for specific interventions based on a single, cross-sectional observational survey. We found evidence of statistical mediation, but testing true causal pathways requires more advanced designs, such as a longitudinal cohort study. Without testing for temporal precedent, stigma could be the cause of lowered social support, for example, rather than the reverse path posited in our model. However, the ASS-S show strong relations with variables that a priori match theory and literature; our findings, although limited, may function as a further test of the scales' validity and relevance to HIV-related behavior. Self-report also limits measurement in our study,96 as our measures are prone to social desirability and recall bias, although the online collection of data along with questions about current and recent experiences may lessen the distorting effects of these forms of bias. 72% of respondents completed our survey, an indication of the potential for selection bias. This may be a function of greater reliance on recruitment through men-seeking-men online venues, but this relatively high completion rate97 points to sustained interest while responding to our study, reflected in end-of-survey comments. Our findings also may not be representative of cisgender MSM in general, as participation was limited to those who use the Internet, although almost all adults96 and most MSM are engaged online,98 in particular to find sex partners.99 In addition, our sample also skewed toward greater financial resources. We adjusted for income in our model, but representative sampling could reveal different associations. In addition, although we took precautions to flag and exclude potentially fraudulent and careless responders, we cannot truly detect and accurately excise these kinds of responses from analyses.

Even with these limitations, our findings have important implications for our collective response to the HIV epidemic. The project contributes to behavioral science by testing a broadly applicable model based on how anal sex stigma impedes the 2 main approaches in preventing HIV: engagement in health care and in safer sex practices, the combination critical to curbing and eventually ending the epidemic.100 Our model also acknowledges that HIV-relevant behaviors occur within a social and relational context8,101,102 and research informed by social processes holds the potential to reveal health factors at levels further upstream from individual behavior that may not yet be well understood but that, consistent with theory on fundamental causes of disease,103 could suggest additional points for intervention on a broader set of health outcomes than just HIV.

CONCLUSIONS

Anal intercourse is both a socially devalued behavior and, under specific circumstances, the most proximate risk factor for HIV among MSM. Our study now quantifies the potential effects of this devaluation. Reluctance to discuss anal sexuality with health workers appears both to derive from anal sex–specific stigma and to impede engagement in prevention services and sexual risk reduction. We did not find evidence of a direct or mediating effect of anal sex concerns on engagement. However, responding to specific questions about anal sex that interest MSM, such as those related to sexual pleasure and well-being, may function as social support and thereby provide avenues to improve comfort discussing anal sexuality and thereby MSM engagement in HIV prevention.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health under grants T32-AI07140 (STD and AIDS Research Training Grant; Principal Investigator: Sheila A. Lukehart, PhD); T32-MH19139 (Behavioral Sciences Research in HIV Infection; Principal Investigator: Theo Sandfort, PhD); and P30-MH43520 (HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies; Principal Investigator: Robert H. Remien, PhD) and by the Bolles Graduate Fellowship through the Department of Psychology at the University of Washington.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beyrer C, Baral SD, Collins C, et al. The global response to HIV in men who have sex with men. Lancet 2016;388:198–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapin-Bardales J, Schmidt AJ, Guy RJ, et al. Trends in human immunodeficiency virus diagnoses among men who have sex with men in North America, Western Europe, and Australia, 2000-2014. Ann Epid 2018;28:874–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones J, Grey JA, Purcell DW, et al. Estimating prevalent diagnoses and rates of new diagnoses of HIV at the state level by age group among men who have sex with men in the United States. Open Forum Infect Dis 2018;5:ofy124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV and gay and bisexual men 2018:1–2. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/group/msm/cdc-hiv-msm.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2019.

- 5.Kasaie P, Pennington J, Shah MS, et al. The impact of preexposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men: An individual-based model. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;75:175–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crepaz N, Lyles CM, Wolitski RJ, et al. Do prevention interventions reduce HIV risk behaviours among people living with HIV? A meta-analytic review of controlled trials. AIDS 2006;20:143–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodger AJ, Cambiano V, Bruun T, et al. Risk of HIV transmission through condomless sex in serodifferent gay couples with the HIV-positive partner taking suppressive antiretroviral therapy (PARTNER): Final results of a multicentre, prospective, observational study. Lancet 2019:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sullivan PS, Alex I, Coates T, et al. Successes and challenges of HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. Lancet 2012;380:388–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, et al. Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for the United States. JAMA 2019;321:844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanchez T, Finlayson T, Drake A, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) risk, prevention, and testing behaviors – United States, National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System: Men who have sex with men, November 2003-April 2005. MMWR Surveill Summ 2006;55:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finlayson TJ, Le B, Smith A, et al. HIV risk, prevention, and testing behaviors among men who have sex with men –National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System, 21 U.S. cities, United States, 2008. MMWR Surveill Summ 2011;60:1–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finlayson T, Le B, Wejnert C, et al. HIV risk, prevention, and testing behaviors – National HIV behavioral surveillance system: Men who have sex with men, 20 U.S. cities, 2011. HIV Surveillance Special Report. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/surveillance/#special. Accessed April 24, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hess KL, Crepaz N, Rose C, et al. Trends in sexual behavior among men who have sex with men (MSM) in high-income countries, 1990-2013: A systematic review. AIDS Behav 2017;21:2811–2834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hammack PL, Meyer IH, Krueger EA, et al. HIV testing and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use, familiarity, and attitudes among gay and bisexual men in the United States: A national probability sample of three birth cohorts. PLoS One 2018;13:e0202806–e0202811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finlayson T, Cha S, Xia M, et al. Changes in HIV preexposure prophylaxis awareness and use among men who have sex with men - 20 urban areas, 2014 and 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:597–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan PA, Mena L, Patel R, et al. Retention in care outcomes for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis implementation programmes among men who have sex with men in three US cities. J Int AIDS Soc 2016;19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Z, Purcell DW, Sansom SL, et al. Vital Signs: HIV transmission along the continuum of care - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:267–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Prevention and Control. CDC Fact Sheet: The nation's approach to HIV prevention for gay and bisexual men. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh S, Bradley H, Hu X, et al. Men living with diagnosed hiv who have sex with men: Progress along the continuum of hiv care - United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014;63:829–833. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller WC, Powers KA, Smith MK, et al. Community viral load as a measure for assessment of HIV treatment as prevention 2013;13:459–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Link BG, Phelan J. Conceptualizing stigma. Ann Rev Soc 2001;27:363–385. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Confronting discrimination: Overcoming HIV-related stigma and discrimination in health- care settings and beyond. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/confronting-discrimination_en.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahajan AP, Sayles JN, Patel VA, et al. Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: A review of the literature and recommendations for the way forward. AIDS 2008;22:S57–S65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herek GM, Chopp R, Strohl D. Sexual stigma: Putting sexual minority health issues in context In: Meyer IH, Northride ME, eds. The health of sexual minorities: Public health perspectives on lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender population. New York: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML, Mirandola M, et al. The geography of sexual orientation: Structural stigma and sexual attraction, behavior, and identity among men who have sex with men across 38 European countries. Arch Sex Behav 2016;46:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smit PJ, Brady M, Carter M, et al. HIV-related stigma within communities of gay men: A literature review. AIDS Care 2012;24:405–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Institute of Medicine. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people. National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolitski RJ, Fenton KA. Sexual health, HIV, and sexually transmitted infections among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in the United States. AIDS Behav 2011;15:9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mantell JE, Kelvin EA, Exner TM, et al. Anal use of the female condom: Does uncertainty justify provider inaction? AIDS Care 2009;21:1185–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krakower D, Mayer KH. Engaging healthcare providers to implement HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2012;7:593–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Calabrese SK, Earnshaw VA, Underhill K, et al. The impact of patient race on clinical decisions related to prescribing HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): Assumptions about sexual risk compensation and implications for access. AIDS Behav 2013;18:226–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chaudoir SR, Wang K, Pachankis JE. What reduces sexual minority stress? A review of the intervention “toolkit”. J Soc Issues 2017;73:586–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cook JE, Purdie-Vaughns V, Meyer IH, et al. Intervening within and across levels: A multilevel approach to stigma and public health. Soc Sci Med 2014;103:101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kutner BA, Simoni JM, Aunon FM, et al. How stigma toward anal sex promotes concealment and impedes health-seeking behavior in the United States among cisgender men who have sex with men. Arch Sex Behav 2020. February 4. doi: 10.1007/s10508-019-01595-9. E-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ayres I, Luedman R. Tops, bottoms and versatiles: What straight views of penetrative preferences could mean for sexuality claims under price waterhouse. Yale LJ 2013;123:714–768. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fields EL, Bogart LM, Smith KC, et al. HIV risk and perceptions of masculinity among young black men who have sex with men. J Adolesc Health 2012;50:296–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoppe T Circuits of power, circuits of pleasure: Sexual scripting in gay men's bottom narratives. Sexualities 2011;14:193–217. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kubicek K, Beyer WJ, Weiss G, et al. In the Dark: Young men's stories of sexual initiation in the absence of relevant sexual health information. Health Ed Behav 2010;37:243–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Middelthon A-L. Being anally penetrated: Erotic inhibitions, improvizations and transformations. Sexualities 2002;5:181–200. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Quinn DM, Earnshaw VA. Understanding concealable stigmatized identities: The role of identity in psychological, physical, and behavioral outcomes. Soc Iss Pol Rev 2011;5:160–190. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am J Pub Health 2013;103:813–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alex I, Bauermeister JA, Ventuneac A, et al. The use of rectal douches among HIV-uninfected and infected men who have unprotected receptive anal intercourse: Implications for rectal microbicides. AIDS Behav 2007;12:860–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Calabrese SK, Rosenberger JG, Schick VR, et al. An event-level comparison of risk-related sexual practices between black and other-race men who have sex with men: Condoms, semen, lubricant, and rectal douching. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2013;27:77–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Colfax G, Vittinghoff E, Husnik MJ, et al. Substance use and sexual risk: A participant- and episode-level analysis among a cohort of men who have sex with men. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:1002–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Collier KL, Sandfort TGM, Reddy V, et al. “This will not enter me”: Painful anal intercourse among Black men who have sex with men in South African townships. Arch Sex Behav 2014;44:317–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Damon W, Rosser BRS. Anodyspareunia in men who have sex with men. Sex Addict Compulsivity 2005;31:129–141. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Myers T, Aguinaldo JP, Dakers D, et al. How drug using men who have sex with men account for substance use during sexual behaviours: Questioning assumptions of HIV prevention and research. Addict Res Theor 2004;12:213–229. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Javanbakht M, Murphy R, Gorbach P, et al. Preference and practices relating to lubricant use during anal intercourse: Implications for rectal microbicides. Sex Heal 2010;7:193–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chow EPF, Cornelisse VJ, Read TRH, et al. Saliva use as a lubricant for anal sex is a risk factor for rectal gonorrhoea among men who have sex with men, a new public health message: A cross-sectional survey. Sex Trans Inf 2016;0:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Noor SW, Rosser BRS. Enema use among men who have sex with men: A behavioral epidemiologic study with implications for HIV/STI prevention. Arch Sex Behav 2014;43:755–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Begay O, Jean-Pierre N, Abraham CJ, et al. Identification of personal lubricants that can cause rectal epithelial cell damage and enhance HIV type 1 replication in vitro. AIDS Res Hum Retro 2011;27:1019–1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mansergh G, Flores S, Koblin B, et al. Alcohol and drug use in the context of anal sex and other factors associated with sexually transmitted infections: Results from a multi-city study of high-risk men who have sex with men in the USA. Sex Trans Inf 2008;84:509–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.The GenIUSS Group. Best practices for asking questions to identify transgender and other gender minority respondents on population-based surveys. Los Angeles: The Williams Institute; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Qualtrics [computer program]. Provo, UT: Qualtrics; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maniaci MR, Rogge RD. Caring about carelessness: Participant inattention and its effects on research. J Res Personal 2014;48:61–83. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Konstan JA, Rosser BRS, Ross MW, et al. The story of subject naught: A cautionary but optimistic tale of internet survey research. J Comp-med Comm 2005;10. [Google Scholar]

- 57.McDavitt B, Mutchler MG. “Dude, you're such a slut!” Barriers and facilitators of sexual communication among young gay men and their best friends. J Adol Res 2014;29:464–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Compendium of evidence-based interventions and best practices for hiv prevention. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/prevention/research/compendium/rr/complete.html. Accessed May 5, 2015.

- 59.Dinenno EA, Prejean J, Irwin K, et al. Recommendations for HIV screening of gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men – United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:830–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015. Sexually Transmitted Infections Guidelines. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/specialpops.htm#MSM. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- 61.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States - 2017 Update 2018. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2017.pdf. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- 62.Smith DK, Herbst JH, Zhang X, et al. Condom effectiveness for HIV prevention by consistency of use among men who have sex with men in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015;68:337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vallabhaneni S, Li X, Vittinghoff E, et al. Seroadaptive practices: Association with HIV acquisition among HIV-negative men who have sex with men. PLoS One 2012;7:e45718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bavinton BR, Prestage GP, Jin F, et al. Strategies used by gay male HIV serodiscordant couples to reduce the risk of HIV transmission from anal intercourse in three countries. J Int AIDS Soc 2019;22:e25277–e25279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Callander D, Newman CE, Holt M. Is sexual racism really racism? Distinguishing attitudes toward sexual racism and generic racism among gay and bisexual men. Arch Sex Behav 2015;44:1991–2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fisher Raymond H, McFarland W. Racial mixing and HIV risk among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav 2009;13:630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, et al. Equity and equality in health structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. Lancet 2017;389:1453–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ayala G, Bingham T, Kim J, et al. Modeling the impact of social discrimination and financial hardship on the sexual risk of HIV among latino and black men who have sex with men. Am J Pub Health 2012;102(Suppl 2):S242–S249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McKechnie ML, Bavinton BR, Zablotska IB. Understanding of norms regarding sexual practices among gay men: Literature review. AIDS Behav 2013;17:1245–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sherbourne CDC, Stewart ALA. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med 1991;32:705–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stucky BD, Gottfredson NC, Panter AT, et al. An item factor analysis and item response theory-based revision of the Everyday Discrimination Scale. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 2011;17:175–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schumacker RE, Lomax RG. A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Routledge; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yu C-Y, Muthén B. Evaluation of model fit indices for latent variable models with categorical and continuous outcomes (Doctoral dissertation). Available at: https://www.statmodel.com/download/Yudissertation.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Matsunaga M How to factor-analyze your data right: Do's, don'ts, and how-to's. Int J Psych Res 2010;3:97–110. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schreiber JB, Nora A, Stage FK, et al. Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. J Educ Res 2006;99. [Google Scholar]

- 76.MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Taylor & Francis; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user's guide. 6th Edition. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Little RJA. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J Am Stat Assoc 1988;83:1198–1202. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brooks H, Llewellyn CD, Nadarzynski T, et al. Sexual orientation disclosure in health care: A systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2018;68:e187–e196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Meites E, Krishna NK, Markowitz LE, et al. Health care use and opportunities for human papillomavirus vaccination among young men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis 2013;40:154–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bernstein KT, Liu K-L, Begier EM, et al. Same-sex attraction disclosure to health care providers among New York City men who have sex with men: Implications for HIV testing approaches. Arch Int Med 2008;168:1458–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.McKirnan DJ, Bois Du SN, Alvy LM, et al. Health care access and health behaviors among men who have sex with men: The cost of health disparities. Health Educ Behav 2013;40:32–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Singh V, Crosby RA, Gratzer B, et al. Disclosure of sexual behavior is significantly associated with receiving a panel of health care services recommended for men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis 2018;45:803–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pachankis JE, Bränström R. Hidden from happiness: Structural stigma, sexual orientation concealment, and life satisfaction across 28 countries. J Consult Clin Psych 2018;86:403–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pachankis JE. The psychological implications of concealing a stigma: A cognitive-affective-behavioral model. Psychol Bull 2007;133:328–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kutner BA, Wu Y, Balán IC, et al. “Talking about it publicly made me feel both curious and embarrassed”: Acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness of stigma-mitigation training for health workers to increase their comfort discussing anal sexuality in HIV services. AIDS Behav 2019. December 19. doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02758-4. E-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Millett GA, Peterson JL, Flores SA, et al. Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: A meta-analysis. Lancet 2012;380:341–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Evans CR. Modeling the intersectionality of processes in the social production of health inequalities. Soc Sci Med 2019;226:249–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nemoto T, Bödeker B, Iwamoto M, et al. Practices of receptive and insertive anal sex among transgender women in relation to partner types, sociocultural factors, and background variables. AIDS Care 2014;26:434–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Marston C, Lewis R. Anal heterosex among young people and implications for health promotion: A qualitative study in the UK. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Baggaley RF, White RG, Boily MC. HIV transmission risk through anal intercourse: systematic review, meta-analysis and implications for HIV prevention. Int J Epidemiol 2010;39:1048–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Herbenick D, Reece M, Schick V, et al. Sexual behavior in the United States: Results from a national probability sample of men and women ages 14-94. J Sex Med 2010;7:255–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Malunguza NJ, Hove-Musekwa SD, Mukandavire Z. Projecting the impact of anal intercourse on HIV transmission among heterosexuals in high HIV prevalence settings. J Theoret Biol 2018;437:163–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.O'Leary A, Dinenno E, Honeycutt A, et al. Contribution of anal sex to HIV prevalence among heterosexuals: A modeling analysis. AIDS Behav 2016;21:2895–2903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Meyer IH. Prejudice as stress: Conceptual and measurement problems. Am J Pub Health 2003;93:262–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fox S, Rainie L. The Web at 25 in the U.S. Pew Research Internet Project 2014. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/02/27/the-web-at-25-in-the-u-s/. Accessed December 21, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hall E, Sanchez T, Stephenson R, et al. Randomised controlled trial of incentives to improve online survey completion among internet-using men who have sex with men. J Epid Comm Health 2019;73:156–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Grov C, Breslow AS, Newcomb ME, et al. Gay and bisexual men's use of the Internet: Research from the 1990s through 2013. J Sex Res 2014;51:390–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Liau A, Millett G, Marks G. Meta-analytic examination of online sex-seeking and sexual risk behavior among men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis 2006;33:576–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Stahlman S, Hargreaves JR, Sprague L, et al. Measuring sexual behavior stigma to inform effective HIV prevention and treatment programs for key populations. JMIR Pub Health Surveill 2017;3:e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Grov C, Ventuneac A, Rendina HJ, et al. Perceived importance of five different health issues for gay and bisexual men: Implications for new directions in health education and prevention. Am J Mens Health 2013;7:274–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ayala G, Makofane K, Santos G-M, et al. Access to basic HIV-related services and PrEP acceptability among men who have sex with men worldwide: Barriers, facilitators, and implications for combination prevention. J Sex Trans Dis 2013;2013:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Phelan J, Link B, Diez-Roux A, et al. “Fundamental Causes” of social inequalities in mortality: A test of the theory. J Health Soc Behav 2004;45:265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Publications; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kutner BA, King KM, Dorsey S, et al. The Anal Sex Stigma Scales: A new measure of sexual stigma among cisgender men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav (In press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]