Abstract

Background:

African American women bear disproportionate human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) burden in the United States, yet are often underrepresented in clinical research. Community engagement may decrease research mistrust and increase participation. We describe strategies used to engage community partners and female participants in a multisite HIV incidence study, HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) 064.

Objectives:

HPTN 064 assessed HIV incidence among women in 10 geographic areas chosen for both high prevalence of HIV and poverty.

Methods:

Women were recruited using venue-based sampling and followed for six to 12 months. Recruitment and engagement approaches aligned with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Director’s Council of Public Representatives (COPR) Community Engagement Framework’s.

Results:

Results showed engagement activities increased rapport and established new partnerships with community stakeholders. Study sites engaged 56 community organizations with 2,099 women enrolled in 14 months. Final retention was 94%.

Conclusions:

The COPR model maximized inclusiveness and participation of African American women impacted by HIV, supported recruitment and retention, and was the cornerstone of community engagement.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, Women, Primary Prevention, Community health research, Power sharing, United States

In the United States, African American communities have a disproportionate burden of HIV.1 In 2016, African Americans represented 12% of the population but accounted for almost one-half of newly identified HIV infections.1 For African American women, the HIV incidence rate is 20 times higher than that of White women, and nearly five times that of Hispanic women.1

Our ability to address and eliminate these disparities requires an understanding of the factors that increase African American women’s vulnerability to HIV. Historically, racial minorities and women are underrepresented in research, and study results often do not account for differences by race/ethnicity.2,3 Although the NIH mandates that women and minority populations be included in NIH-funded clinical research,4 substantial barriers to African American women’s participation remain. Several well-documented factors are known to affect minority participation in research, including lack of trust, power differences, limited access to health care and research opportunities, and lack of perceived relevance.2,3,5 Women living in poverty may experience additional barriers to participating in clinical research studies, including access to childcare and transportation.5

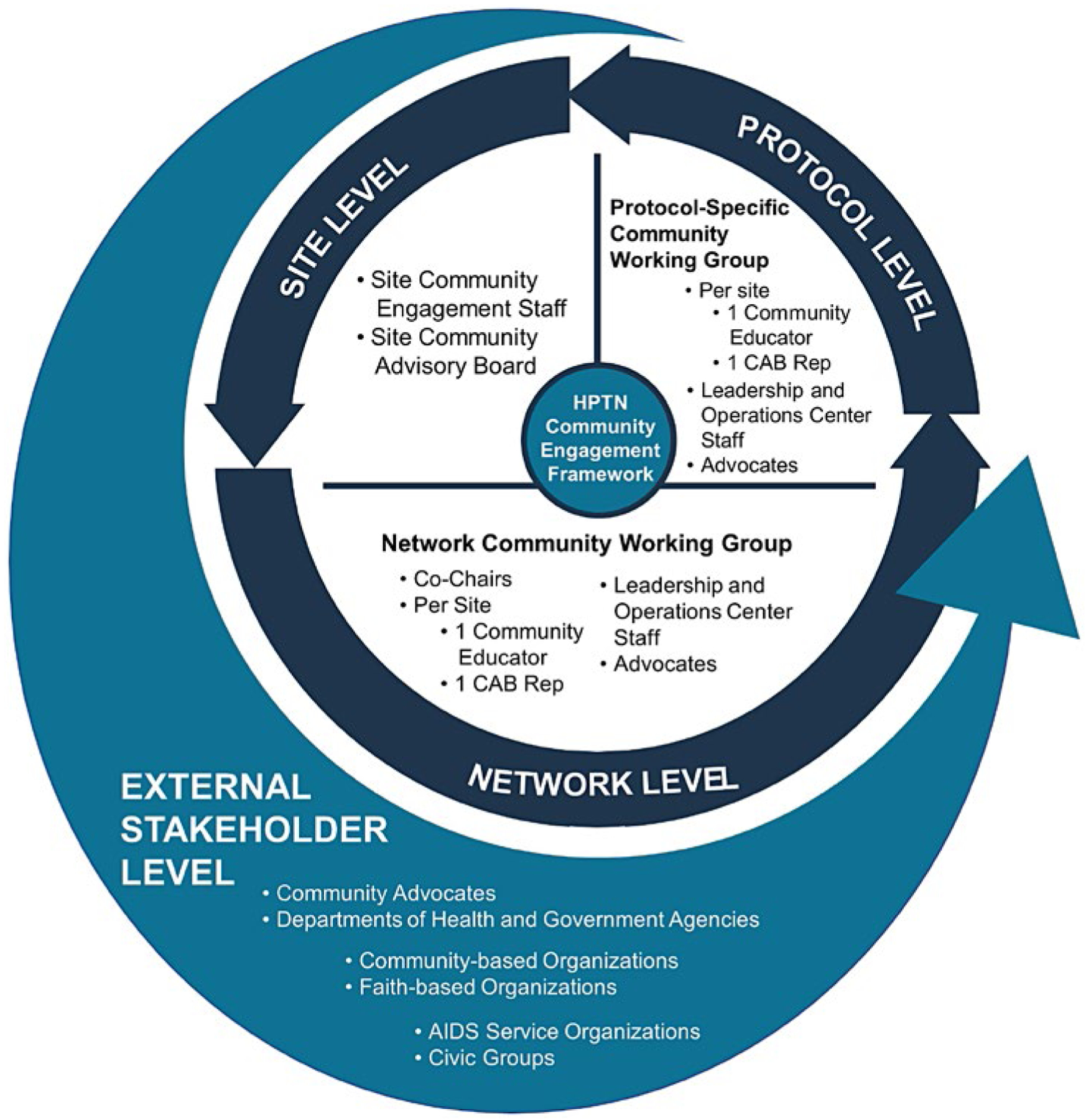

African American communities in the United States may also mistrust researchers largely due to documented misconduct of human subjects and ethical violations.6 One effective strategy to decrease public mistrust and increase participation of African American communities in HIV prevention research is community engagement.3,7 The goals of community engagement are to build trusting relationships, create partnerships, share resources, create and improve communications, and improve health outcomes.8 The NIH defines community engagement as “a process in research of inclusive participation that supports mutual respect of values, strategies, and actions for authentic partnership of people affiliated with or self-identified by geographic proximity, special interest, or similar situations to address issues affecting the well-being of the community focus.”8 The use of community advisory boards (CABs) is a critical strategy to achieve the goals of community engagement.3,9 CABs, which typically include a representative group of non-researchers, have been a part of HIV research since the late 1980s.9,10 Originally, CABs provided consultation and communicated community needs, which later expanded to a collaborative relationship with researchers.9,11 CABs have been a required component of clinical research sites conducting HIV prevention and treatment research funded by the NIH since 1996 and are a key component of the HPTN community engagement framework (Figure 1).9,12 Although establishing a CAB is a vital component of community engagement, this method alone does not comprise a comprehensive community engagement strategy.13 Additional community engagement approaches include planning with community input, increased and consistent communication to the community and study participants, providing community resources, and involving minority researchers.3,13 Some other ways to engage and greatly impact the community are to provide trainings on health or resources available to bring awareness and increase its capacity; support events by attending or volunteering; foster collaborative programs such as health fairs, and create ongoing, sustainable partnerships.14

Figure 1. Community engagement frameworks.

In HPTN, the Network Community Working Group (Figure 1) serves as the research network’s community advisory structure. The Network Community Working Group facilitates inclusion of representatives from the research community as partners in the HPTN research agenda. CAB representatives and community education staff participate in the Network Community Working Group, in community educator conference calls, HPTN protocol teams, and other network committees. Additionally, once a protocol is approved for development, a protocol-specific community working group is formed. The goals of the protocol-specific community working group are to:

Provide input into protocol development,

Adapt sample informed consent forms for local use and develop other study-related materials,

Participate in protocol training and regional workshops,

Help to inform recruitment and retention strategies, especially for harder to reach populations,

Assist in monitoring any emerging community issues while a study is ongoing, and

Facilitate accurate study results dissemination.

Although a growing body of literature supports the role of community engagement in HIV prevention research and potential frameworks for doing so, few studies describe detailed methods applied by research teams in field settings.8 This manuscript presents the community engagement strategy used by HPTN 064, an NIH-funded, large, multisite trial that enrolled women at increased risk of HIV acquisition in the United States. We describe the methods used throughout all phases of the research process to engage and sustain community partnerships and stakeholder relationships. Our approach is within the NIH Director’s COPR Community Engagement Framework, a set of core principles used to build community rapport and establish mutual respect between researchers and community stakeholders.8 The COPR framework emphasizes community engagement as a fundamental tenet of research in community settings with mutual exchange of experience and expertise between researchers and community members throughout the conception, implementation, and conclusion of the research. The model is grounded in the assumption that public participation in research enhances the quality of the research produced and was developed by an NIH work group composed of academic and community partners.8 COPR has a number of similarities to the principles of community-based participatory research (CBPR). Both COPR and CBPR frameworks are rooted in community involvement and action throughout all phases of the research process.14 CBPR differs from COPR in the identification of the research focus by the community. CBPR implementers consult with the community representatives to develop the concept prior to protocol development and implementation.14 This article describes application of the COPR framework, its set of core principles, each principle’s associated values, and describes how the framework was adopted by a larger NIH-funded clinical trial network to complete a HIV prevention research study with African American women.

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION AND METHODS

Participants

HPTN 064 was a multisite, longitudinal cohort study designed to estimate HIV incidence among women living in communities with prevalent HIV and poverty enrolled by clinical research sites in Atlanta and Decatur, Georgia; Washington, DC; Baltimore, Maryland; Bronx and Harlem, New York; Durham and Raleigh, North Carolina; and Newark, New Jersey.15 Eligible women lived in census tracts or zip codes with the highest prevalence of poverty and HIV, reported unprotected sex with a man in the previous six months, and reported that either they or their male partner(s) had a characteristic that increased vulnerability to HIV acquisition (e.g., history of incarceration, sexually transmitted infection, substance use; Table 1).16 Women were recruited using venue-based sampling techniques and followed for 6 or 12 months, depending on their date of enrollment. Participants received HIV rapid testing and audio computer-assisted self-interviews at baseline and at 6-month intervals for up to 12 months. A subset of women enrolled at clinical research sites in Georgia, District of Columbia, New York, and North Carolina participated in qualitative interviews and focus groups. All participants received monthly calls to update locator information. Women were compensated for in-person follow-up visits and phone locator-update calls. Clinical research sites implemented multifaceted retention strategies (e.g., home visits, holiday and birthday cards, and tear-off flyers in recruitment areas encouraging return visits) to keep attrition low. Compensation amounts varied by clinical research site. The protocol, qualitative interview guides, focus group guides, community engagement work plans, recruitment and retention plans, and compensation amounts were reviewed and approved by local institutional review boards. All women provided written informed consent prior to study participation. Study activities are described in detail elsewhere.15–17

Table 1.

HPTN 064 Participant Baseline Characteristics (n = 2,099)

| Variable | Median (IQR) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | 29 (23–38) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Black | 1802(86) |

| White | 143 (6.8) |

| Mixed | 54 (2.6) |

| Other | 100 (4.8) |

| Hispanic | 245 (11.7) |

| Less than high school education | 777 (37) |

| Abuse history | |

| Physical, emotional, sexual abuse, and/or feeling unsafe | 811(39) |

| Childhood abuse | 934 (44) |

| Mental health | |

| Symptoms indicative of depression | 692(33) |

| Symptoms indicative of post-traumatic stress disorder | 600 (29) |

| Sexual risk behaviors | |

| Multiple partners | 776 (37) |

| Non-monogamous sexual partner | 763(36) |

| Condom use at last vaginal sex | 376 (18) |

| Exchange of sex for drugs, money, or other commodities | 776 (37) |

| Self-reported sexually transmitted infection | 232 (11) |

| Homeless | 182 (9) |

| Unmet need for medical care | 417(20) |

| Illicit nonalcohol drug use* | 726 (35) |

| Incarceration in the last 5 years† | 848 (40) |

| Binge drinking‡ | 1300(62) |

| Homeless | 182 (9) |

| Reported food insecurity | 971(46) |

| Financially responsible for this number of children | |

| 0 | 974 (47) |

| 1 | 465 (22) |

| ≥2 | 644(31) |

Excludes cannabis.

Part of eligibility criteria.

Defined as four or more drinks at one time (e.g., during the morning, afternoon, or evening).

Community Engagement Activities

Community engagement was critical in the conduct of HPTN 064 and spanned all phases of the research process. Community engagement activities fell within one of five core principles designed to create and sustain genuine community- researcher partnerships to promote accountability and equity.8 These principles, corresponding activities, and outcomes aligned with the NIH Director’s COPR model for community engagement, included 1) mutual understanding of meaningful community involvement and scope, 2) strong research community partnerships, 3) equitable power, 4) capacity building, and 5) effective dissemination. Responsibilities of stakeholders such as clinical research site research staff, clinical research site CABs, protocol teams, leadership and operations center staff, and the protocol-specific community working group are outlined in Table 2. Stakeholder functions and relationships are also described in Table 2.

Table 2.

HPTN 064 Responsibility Matrix with Modified Activities and Values from the National Institutes of Health Director’s Council of Public Representatives (COPR) Core Principles

| CWG | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutual understanding of meaningful community involvement and scope | Community involvement processes understood | Network CWG, CRS CABs and external community stakeholders informed of community engagement processes | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Generated understanding of and support for the HPTN 064 research initiatives. | ||

| Research goals are clear and relevant | CAB/Stakeholders buy-in sought prior to completing 064 CRS application | ✓ | ||||||

| Strong research community partnerships | Community-investigator partnership is strong | Bi-directional information exchange between community and researchers | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Created culturally responsive community/research partnership with formal structures Funded grant with university and community co-principal- investigators |

| Community representatives appointed to the protocol team | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| All partners receive equal respect | Ongoing training in good clinical practice and human protections | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Informed consent documents reviewed for accuracy and readability | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Regular study updates provided | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Equitable power | Communities and investigators share power and responsibility equitably | Development of HPTN 064 CWG | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Identified potential barriers to study implementation Strengthened overall study design Developed culturally appropriate study materials Completed accrual in 14 months 94% participant retention rate |

|

| Study specific trainings to ensure understanding of the protocol and procedures | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Review qualitative data and developed qualitative data analysis code book | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Local ethnography to inform recruitment venue selection | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Data collection forms reviewed ensure understanding and readability | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Diverse perspectives and populations are included in an equitable manner | Substantive feedback integrated into protocol | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Input on development of recruitment and retention plans | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Cultural responsiveness training Submission and selected of study logo | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| ✓ | ||||||||

| Identification of additional community stakeholders | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Capacity building | The research project is mutual benefit for all partners | Developed community resource guide | ✓ | ✓ | Established participant referral systems Provision of trained HIV counselors and phlebotomist to provide testing at community events sponsored by partnering agencies Distribution of study information and condoms at community events |

|||

| HPTN 064 CWG training | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Community partnerships established | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Volunteerism at community events and supported local businesses | ✓ | |||||||

| Communities and investigators have opportunities to build capacity | Personal safety trainings | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Retention workshop | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Community research priorities to inform network research agenda | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Effective dissemination | Transparent results dissemination process | Communication plan and informative materials developed | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Study results released to study participants and scientific community simultaneously Developed culturally appropriate study dissemination materials 36 traditional and social media outlets reported on primary study findings CWG representatives produced a total of 10 abstracts for HIV prevention conferences that were accepted as posters (2), oral presentations (6), and workshops (2) |

| Partners develop appropriate dissemination materials and identify appropriate distribution platforms | Network CWG and local CABs were informed of data release timeline | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Input provided on the development of community results brochure and fact sheet | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Press release reviewed and participation in social media study related messaging | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Presentations provided during local community gratitude celebrations to inform of study results | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| HPTN 064 national and local study results | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| HPTN 064 documentary video | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Inclusion of community representatives on manuscript writing teams | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Presentations at national HIV prevention conferences | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

ACASI = audio computer-assisted self-interview; CAB = community advisory board; CBO = community-based organization; CRS = clinical research site; CWG = community working group; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; HPTN = HIV Prevention Trials Network; LOC = HPTN leadership and operations center; NIH = National Institutes of Health.

Comprehensive outcomes: improved community rapport and newly established partnerships with community stakeholders through engagement of 56 national and local community stakeholder organizations during the protocol conceptualization, implementation, and dissemination phases of the HPTN 064 protocol. The Comprehensive Outcomes for the HPTN 064 study emerged from the confluence of all these elements.

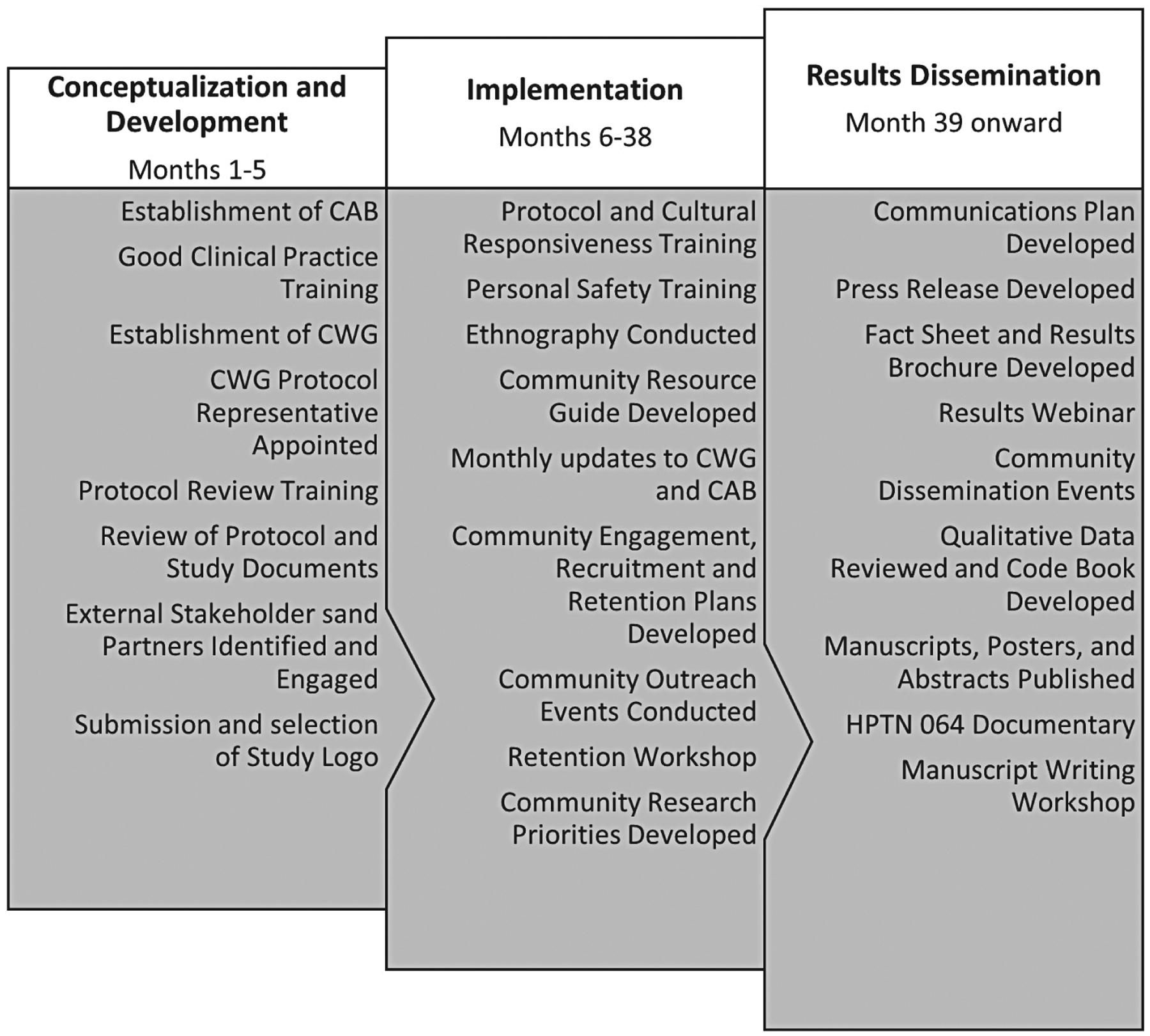

Protocol Conceptualization and Development.

Numerous activities were conducted during the 5-month period in which the protocol was developed (Figure 2). These activities helped to ensure adequate community engagement during the protocol conceptualization and development phase of HPTN 064, most notably development of community advisory bodies and solicitation of community feedback on study design. Each clinical research site had an active CAB that served as a voice for the community and study participants. Active CAB involvement fostered partnerships between researchers and local study communities and helped the investigation team better understand community needs and culturally appropriate ways to access the community. CABs reviewed the study protocol, helped to identify potential recruitment venues, and aided in the development of effective recruitment and retention strategies. CAB members were of diverse backgrounds, including sex, race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, national origin, age, disability, socioeconomic status, and HIV status. CAB membership varied at each clinical research site, but CABs were required to have 40% representation of community constituents who represented the lived experiences of women enrolled in HPTN 064. Persons were thus able to contribute professional or personal experiences, including people living with HIV/AIDS, current and/or former study volunteers, and representatives from community-based organizations (CBOs). CAB members at the clinical research sites were not paid staff members, thus maximizing CAB autonomy and reducing the potential for conflict of interest. Reimbursement was provided to all CAB members to offset costs of participation in the advisory process (i.e., transportation, meals, and time).

Figure 2. HPTN 064 study timeline.

The HPTN 064 Community Working Group was linked to, but separate from, the clinical research site CABs (Table 2). The HPTN 064 Community Working Group provided feedback on study design, eligibility criteria, recruitment and retention strategies, and guidance to the protocol team and sites throughout study implementation and closure. The HPTN 064 Community Working Group included two community representatives from each study site (one community educator and one CAB member), as well as representation from the study funder (NIH) and a national community advocacy group (Community HIV/AIDS Mobilization Project). The HPTN 064 Community Working Group met by conference call monthly to discuss study-related challenges and share effective solutions. Two HPTN 064 Community Working Group representatives were appointed to the protocol team to serve as liaisons between the HPTN 064 Community Working Group and the protocol team.

The HPTN 064 Community Working Group worked in partnership with the HPN 064 protocol team. The HPTN 064 protocol team was responsibile for scientific and operational leadership in the development, implementation, and day-to-day oversight of HPTN 064 and dissemination of the study results. Recognizing the importance of representation of women in the design and implementation of the study, the protocol team was intentional in its composition of 35% women of color and 85% women. Additionally, all the study coordinators at the clinical research sites were women of color and 95% of the community engagement staff as sites were women of color.

Local investigators and community representatives worked in partnership to understand the HPTN community engagement processes and develop mutually agreed upon meaningful engagement practices enacted at local clinical research sites. The HPTN leadership and operations center provided several trainings to community and site representatives to ensure that all partners could effectively communicate key trial issues. For example, clinical research site staff and CAB representatives were required to complete training in good clinical practice, human subject protections, and cultural responsiveness; and to participate in study-specific trainings to ensure a thorough understanding of protocol and procedures.

Community representatives provided input on the study protocol and participant recruitment, which facilitated trial implementation. Examples of community input included the appropriate use of a mobile health vehicle for field recruitment, design of study logo, development of a community resource directory, and community engagement processes. In addition, community representatives reviewed study documents (e.g., participant informed consent and compared the forms with information in the protocol to confirm accuracy). The HPTN 064 Community Working Group worked with the HPTN leadership and operations center to improve document readability by using nontechnical language. Prior to the protocol review, the HPTN leadership and operations center conducted a 2-day, in-person training for HPTN 064 Community Working Group representatives. The training focused on building knowledge and skills to review protocols and provide feedback to protocol teams. These efforts promoted the community-investigator partnership and ensured bidirectional information exchange among CABs, site staff, HPTN 064 Community Working Group, the funder, and protocol leadership. Notably, HPTN 064 Community Working Group and clinical research sites CABs provided feedback that was integrated into the research protocol. For example, early versions of the study protocol used the term “high-risk area” to refer to census tracts and zip codes with prevalence of poverty and HIV. Due to the community concerns, that use of the “high-risk area” would stigmatize residents of these areas, the HPTN 064 protocol team issued a memo explaining the science behind the terminology, emphasizing that the term did not reflect behaviors of residents, but rather the social and structural factors that increase vulnerability to HIV. Hence this feedback from the community, “high-risk area” was not used in any materials intended for public dissemination.

Implementation.

Community engagement activities during this 32-month period ensured ongoing rapport building with study clinical research sites and capacity building within community advisory bodies. Community representatives provided advice on scientific, ethical, and operational issues regarding any changes to study design, recruitment, and protection of study volunteers. Community representatives also informed researchers of issues or concerns that may affect the successful implementation of the study.

The HPTN 064 Community Working Group, clinical research site CABs, and external community stakeholders were informed of community engagement processes on a regular basis through various mechanisms including conference calls, face-to-face meetings, and social media. During conference calls the HPTN064 community working group provided guidance to the protocol team on emergent community issues. In addition to the regular study updates, capacity-building trainings were developed and implemented for clinical research site CABs and the HPTN 064 Community Working Group. These included clinical research trainings, good participatory practices training, and engagement of community stakeholders. The HPTN leadership and operations center provided weekly study updates to external community stakeholders using Facebook and Twitter. Social media posts highlighted community engagement and recruitment activities conducted by clinical research sites. With guidance from local CAB representatives, HPTN 064 clinical research sites developed community resource guides for study participant referrals and CBO use. The guides used culturally competent service providers and CAB approved local businesses.

Clinical research sites also volunteered at local community events and with local CBOs to build community rapport and support local businesses. Three clinical research sites provided HIV counselors and phlebotomists to offer HIV testing at community events sponsored by partnering CBOs. Clinical research sites representatives distributed study information, branded study items (e.g., pens, T-shirts, hats) and condoms at community health fairs and events. Some clinical research sites developed formal business agreements with community partners or their local CAB for some aspect of study implementation including community engagement, outreach, ethnography, recruitment, and retention. Clinical research sites also patronized local businesses for printing study materials and giveaway items and providing meals for CAB meetings and trainings.

Results Dissemination.

Analysis detailing the primary study outcome, HIV incidence among U.S. women at increased risk for acquiring HIV, were completed in 2013. As the HPTN 064 protocol team prepared to release results, they consulted extensively with the HPTN 064 Community Working Group while clinical research sites consulted with their local CABs. The HPTN 064 Community Working Group and CABs were informed of the results dissemination timeline. The HPTN 064 Community Working Group provided substantive feedback on the HPTN 064 communications plan and dissemination materials developed for use at HPTN 064 clinical research sites. These materials included a study fact sheet, results brochure, and press release documents. Clinical research sites staff and HPTN 064 Community Working Group representatives also reviewed qualitative data and developed a qualitative data analysis code book for HPTN 064.

National and local community representatives disseminated study information through two social media platforms, Facebook and Twitter. Clinical research sites worked with their local CABs to develop site-specific dissemination materials and identify appropriate distribution platforms for study results. Study staff gave presentations for study participants, community representatives, advocates, and CBOs to inform communities of the study results and thank them for their participation and help. National dissemination webinars provided communities outside of the research areas a means to understand and ask questions about study results. These webinars targeted advocates, AIDS service organizations, and CBOs that provided services to women who reside in high HIV prevalence areas in the United States. Similarly, HPTN 064 study results were presented at national and international HIV prevention conferences to disseminate findings to HIV prevention advocates and researchers. However, as demonstrated by the current manuscript, the HPTN 064 site and protocol team members continue to disseminate study findings in academic and nonacademic settings.

The HPTN leadership and operations center developed an HPTN 064 documentary video, showcasing two participants and two CAB representatives. The video can be found at https://vimeo.com/343284219/49513d68f3. The video provided the public with a better understanding of the challenges of living in high HIV prevalence and poverty areas. The video was showcased at an international conference, through webinars, and local clinical research sites events. After the release of results, the protocol team sought community representatives to participate on manuscript writing teams and help author sections of a book that used qualitative interview and focus group data collected during HPTN 064. A writing workshop was conducted to increase knowledge of the manuscript writing process and writing skills to ensure HPTN 064 Community Working Group representatives participated on the writing teams.

ACTIVITIES AND OUTCOMES

Implementation of multiple community engagement activities aided in successfully engaging the at risk population and attaining enrollment of 2,099 women from community-based venues in 14 months (Table 1). Retention remained high throughout the study with 93% at 6 months and 94% at 12 months.17 The majority of women enrolled were Black (86%). By design, women lived in areas with high HIV prevalence and poverty. Forty percent reported being incarcerated in the last 5 years, and 35% had illicit (nonalcohol) drug use. Nearly 40% of participants had less than a high school education, 46% reported not having enough food for themselves or their family in the prior 6 months, and 53% were responsible for at least one child under 18 years of age. Only 18% of women reported using a condom the last time they had vaginal sex. The incidence rate in HPTN 064 was approximately six times greater than Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates among Black women of similar age.16 HIV incidence was 0.32 per 100 woman-years.

Community engagement activities increased community rapport and established new partnerships with community stakeholders. Study clinical research sites engaged 56 national and local community stakeholders during protocol conceptualization, implementation, and dissemination. Clinical research sites worked with stakeholders to identify potential barriers to study implementation, generate understanding of and support for research initiatives, and inform key organizations/advocates of HPTN research studies focusing on women at risk of acquiring HIV. Additionally, clinical research sites conducted outreach events (n = 2,095) in the communities where recruitment occurred.5 Clinical research sites established partnerships with local CBOs and providers with whom they could provide referrals for study participants. These organizations were included as part of local referral guides that clinical research sites still use. Partnerships developed during the study were sustained by every site. All sites continue to work with community organizations in some capacity. For example, clinical research sites would refer participants for services offered by community based organizations such as substance use recovery groups, food banks, mental health, and homeless shelters.

HPTN 064 representatives worked with the HPTN leadership and operations center to develop the study press release18 and supporting results dissemination materials. When HPTN 064 results were released, approximately 36 traditional and social media outlets reported on primary initial study findings (e.g., Jet Magazine, Huffington Post, Facebook, and Twitter).

HPTN leadership and operations center provided HPTN 064 Community Working Group representatives seven training sessions to increase their capacity related to research conceptualization, conduct, and results dissemination. As a result, HPTN 064 Community Working Group representatives worked with writing teams to produce three manuscripts5,17,19 and eight abstracts that were accepted as two posters,20 six oral presentations,21–26 and one workshop27 at four HIV prevention conferences. In addition, community coauthors were included in nine of 13 book chapters28 generated using HPTN 064 qualitative data. Lastly, HPTN 064 success positively contributed to a 7-year renewal of HPTN NIH funding at participating sites due in part to excellent recruitment and retention of female participants. Additionally, three of the six sites used HPTN 064 data to secure grant funding to conduct research to enhance the communities where the study was completed. In one instance, a community partner served as co-principal investigator of the resulting award.

DISCUSSION

African American women bear the disproportionate burden of HIV/AIDS among all women and are historically underrepresented in clinical trials in research. By all standards, HPTN 064 was successful in enrolling and retaining large numbers of minority women at elevated risk of HIV acquisition. HIV incidence among women enrolled in HPTN 064 was six times higher than the national estimate of HIV incidence in the general population of African American women of similar age.15 This was accomplished from across six geographic areas in the eastern United States extending from New York City to Atlanta.

Despite the complexity of recruiting women from impoverished neighborhoods with high HIV prevalence, HPTN 064 was immensely successful, enabled, we believe, by its collaborations, partnerships, and community engagement. Another multisite cohort study conducted around the same time period reported 83% retention at 12 months utilizing similar recruitment strategies and enrollment criteria.29 Brown-Peterside et al.,30 who reported 67% retention of a predominantly African American and Latina cohort of women at increased risk of HIV in the Bronx, cited the need for community engagement as a strategy to promote recruitment and retention in future studies. Subsequent cohort studies from this group reported improvements in both these areas.31 Our experience suggests that applying the core principles of the COPR model ensured inclusiveness and participation of African American women impacted by HIV from study inception to results dissemination, and served as the cornerstone of community engagement activities. The COPR framework was flexible and allowed adaptation by different communities and built on existing strengths of study participants. The core principles and values were applied among all clinical research sites, but operationalization varied for each value according to what worked best within that community.

Study success, as evidenced by rapid recruitment and high retention, was grounded in the strong emphasis on community engagement throughout the research process. HPTN 064 found that pre-implementation work was pivotal to success and laid the foundation for community engagement. Working with the CAB, community representatives, and external stakeholders was crucial to initial study phases. These reciprocal relationships were mutually beneficial through all study phases. Technical trainings were provided on how to review protocols and on the research process. The community working group provided feedback on the protocol, informed consent, and recruitment plan. They reviewed the informed consent to ensure that it was linguistically appropriate and used nontechnical language. The CAB reviewed the recruitment plan to ensure that it was appropriate for their communities, which assisted clinical research sites and the HPTN 064 protocol team in understanding community needs and how to effectively navigate in them.

Community representatives, CBOs, and stakeholders work toward equal partnership when they are involved in all aspects of the research process.8,32 We found it to be imperative to do so as it helped build trust, allowed for mutual understanding of issues surrounding research, and ensured that values and cultural differences among participants were respected. Mutual understanding of meaningful community involvement and scope is achieved when researchers and community stakeholders gain thorough understanding of the research proposed and how community engagement activities will impact the research being developed and/or implemented.8,32 The relationships built with CBOs were reciprocal and mutually beneficial. Providing the opportunity for decision making bolsters respect, rapport, accountability, and community ownership of the research.8,33 Increasing a community stakeholder’s capacity to understand and conduct research encouraged community representatives to provide substantive feedback and improve the research design.8 As gatekeepers to the communities, their willingness to learn and share their knowledge helped us to gain access to the study communities. Involving the HPTN community working group, CAB, and community representatives along with providing trainings and updates on the study from protocol conceptualization through completion allowed for the development of trust and open dialogue in the relationship between the researchers and community, which contributed to the success of HPTN 064. We have included a study timeline in Figure 2, which shows the community engagement activities from protocol conceptualization to results dissemination.

Community partners held the sites accountable for promised deliverables, and because of the follow-through, these relationships were sustained. One community partner shared that because of the successful, trusting partnership developed with the research site they moved forward in participating with other research studies. Sites not only shared social resources, but made sure that financial resources were vested into the communities along with the power to make decisions on how those resources were used. For example, sites worked with CBOs to write grants for funding using data that was collected in HPTN 064. Lastly, one of the site’s community member is a co-principal investigator on a community research study, demonstrating true power sharing.

Transparency is a pivotal component in gaining community trust.8,32 HPTN 064 investigators were committed to developing, maintaining, and sustaining the relationships with the community before, during, and after the research was completed. Community stakeholders and researchers should provide input on disseminating research results, ensuring that the results are understood by communities where the research was conducted.8,32 Historically, clinical research trials that did not successfully integrate community partners in the early development stages failed due to lack of communication among researchers, participants, and the community, as evidenced by early pre-exposure trials.34 All sites followed the communication plan and ensured that not only the research participants but also the community representatives, CAB, and stakeholders were informed of the study results and findings. The HPTN 064 team worked to ensure that results from the study were relevant, did not marginalize communities or study participants, and were accessible to community and scientific stakeholders through an array of social and traditional media venues. The activities supported mutual respect, and bidirectional and continuous communication, which are key to engaging and building community.14,32

Although HPTN 064 was successful in the recruitment and retention of a minority women, we are unable to evaluate the contribution of each activity on study outcomes. Future research should consider evaluating and monitoring outcomes, including return on investment of community engagement activities.3 As Stewart, et al. stated, we need to evaluate whether or not community engagement activities for research are responsive to the community needs and concerns.3 Evaluation plans should account for challenges related to the effects of partnerships on study outcomes related to upstream and downstream determinants.

LESSONS LEARNED

HPTN 064 demonstrated that planned community involvement which included members of the at risk group in meaningful ways in study planning and implementation impacts study success. Culturally competent clinical research site staff built upon established partnerships with community collaborators on the local level to inform recruitment and retention efforts and to develop a resource network for information and referral for study participants. Leadership and operations center and clinical research site level education projects built the capacity of community members to participate in the research process and play an essential role in the review of study materials. Clinical research site staff working with representatives from the at risk group enriches the knowledge base of both and further enhances the ability of staff to better understand the experiences of community representatives and use this awareness to develop science relevant to the circumstances of the community. Engagement initiatives that include community members facilitates awareness of and removal of impediments to clinical trial participation.8,32

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the study participants, community stakeholders, and staff from each HPTN 064 study site and the HPTN 064 Community Working Group. In addition, they acknowledge Kathy Hinson, Lydia Soto Torres, Sally L. Hodder, Jessica Justman, Shobha Swaminathan, Wafaa El Sadr, Lynda Emel, LaTanya Lewis Johnson, Lorenna Rodriguez, Christopher C. Watson, Cheryl Cokley, Rhonda White, and Jontraye Davis. This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institute on Drug Abuse, and National Institute of Mental Health (cooperative agreement nos. UM1 AI068619, UM 1AI068617, and UM1 AI068613); University of North Carolina Clinical Trials Unit (AI069423); University of North Carolina Clinical Trials Research Center of the Clinical and Translational Science Award (RR 025747); University of North Carolina Center for AIDS Research (AI050410); Emory University HIV/AIDS Clinical Trials Unit (5UO1AI069418), Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI050409), and Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1 RR025008); The Terry Beirn Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS Clinical Trials Unit (5 UM1 AI069503–07); The Johns Hopkins Adult AIDS Clinical Trial Unit (AI069465) and The Johns Hopkins Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1 RR 25005); and the HPTN Scholars Program. Ms. Haley’s time was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number F31MH105238 and the Robert W. Woodruff Pre-Doctoral Fellowship of the Emory University Laney Graduate School. The views expressed herein are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institutes of Health, the HPTN, or its funders.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among African Americans [updated 2016; cited 2018 May 15]. www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/group/racialethnic/africanamericans/cdc-hiv-africanamericans.pdf

- 2.Cottler LB, McCloskey DJ, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, et al. Community needs, concerns, and perceptions about health research: Findings from the Clinical and Translational Science Award Sentinel Network. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(9):1685–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stewart MK, Felix HC, Olson M, et al. Community engagement in health-related research: A case study of a community-linked research infrastructure, Jefferson County, Arkansas, 2011–2013. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12:E115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NIH Policy and Guidelines on The Inclusion of Women and Minorities. [updated 2001]. http://grants.nih.gov/grants/funding/women_min/guidelines_amended_10_2001.htm

- 5.Haley DF, Golin C, El-Sadr W, et al. Venue-based recruitment of women at elevated risk for HIV: An HIV Prevention Trials Network study. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2014;23(6):541–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas SB, Crouse Quinn S. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study, 1932 to 1972: Implications for HIV education and AIDS risk education programs in the Black community. American Journal of Public Health. 1991:1498–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson DA, Joosten YA, Wilkins CH, Shibao CA. Case study: Community engagement and clinical trial success. Clin Transl Sci. 2015:388–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmed M, Palermo AM, Ann-Gel S. Community engagement in research: Frameworks for education and peer review. Am J Public Health. 2010:1380–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morin SF, Maiorana A, Koester KA, Sheon NM, Richards TA. Community consultation in HIV prevention research: A study of community advisory boards at 6 research sites. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33(4):513–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacQueen KM, Bhan A, Frolich J, Holzer J, Sugarman J, and the Ethics Working Group of the HIV Prevention Trials Network . Evaluating community engagement in global health research: The need for metrics. BMC Medical Ethics. 2015:16:44 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4488111/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Isler MR, Miles MS, Banks B, et al. Across the Miles: Process and Impacts of Collaboration with a Rural Community Advisory Board in HIV Research. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2015;9(1):41–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Members CRWG. Recommendations for community involvement in National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases HIV/AIDS Clinical Trials Research. 2009.

- 13.Ying-Ru M, Chu C, Ananworanich J, Excler JL, Tucker JD. Stakeholder engagement in HIV cure research: Lessons learned from other HIV interventions and the way forward. AIDS Patient Care STD. 2014:389–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rhodes S, Tanner A, Mann-Jackson L, et al. Promoting community and population health in public health and medicine: A stepwise guide to initiating and conducting community-engaged research. J Health Disparities Res Pract 2018;11(3):16 A–31 A. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hodder SL, Justman J, Hughes JP, et al. HIV acquisition among women from selected areas of the United States: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(1):10–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sally Hodder M,, Jessica Justman M, Danielle Haley M, et al. Challenges of a hidden epidemic: HIV prevention among women in the United States. J Acquir Immune Deficiency Syndr. 2010:S69–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haley D, Lucas J, Golin C, et al. Retention strategies and factors associated with missed visits among low income women at increased risk of HIV acquisition in the US (HPTN 064). AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2014;28(4):206–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.HIV Rates for Black Women in Parts of the US Much Higher than Previously Estimated [press release] 2012, HIV Prevention Trials Network, https://www.hptn.org/news-and-events/press-releases/hiv-rates-for-black-women-parts-of-us-much-higher-than-previously [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen I, Clarke W, Ou S-S, et al. Antiretroviral drug use in a cohort of HIV-uninfected women in the United States: HIV Prevention Trials Network 064. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(10):e0140074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Golin C, Haley D, Frew P, et al. Male attitudes toward HIV testing among men in four US cities. Paper presented at: 6th IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Preventions Rome, Italy; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Douglas M, DeShields R, King G. Transforming Black America’s HIV burden: Black Nurses’ roles in research engagement. Paper presented at: 38th annual conference of the National Black Nurses Association San Diego, California; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haley D, Lucas J, Waller H, et al. Identifying and retaining US women at increased risk of HIV infection. Paper presented at: National HIV Prevention Conference Atlanta, Georgia; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frew P, Del Rio C, O’Leary A, et al. Multilevel determinants of women’s HIV risk in the United States: Qualitative implications for intervention development from the HIV Prevention Trial Network’s (HPTN) Women’s HIV SeroIncidence Study (ISIS ). Paper presented at: 6th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention Rome, Italy; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merchant S, Waller H, Jones L, et al. Contextual factors associated with low condom use among women at high-risk for HIV/AIDS in urban environments. Paper presented at: VOICES Conference 2011: Mapping Our Way Washington, DC; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haley D, Lucas J, Hughes J, Hodder S. HPTN 064 (ISIS): Identifying and retaining US women at greatest risk of HIV Infection. Paper presented at: 1st International Workshop on HIV and Women Washington, DC; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haley DF, Parker K, Dauria E, et al. (2015–2016). Health and policy implications of housing conditions, neighborhood environments, housing choice, and mobility among women living in high poverty and HIV prevalence areas in the United States (US): HPTN 064 American Public Health Association Annual Meeting and Expo, Chicago, Illinois. [Google Scholar]

- 27.King G, Lucas JP. Diverse approaches to HIV prevention research with Black Women: Lessons learned from HPTN’s community engagement successes. Paper presented at: 39th National Black Nurses Association Annual Institute and Conference Indianapolis, Indiana; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Leary A, Frew P. Poverty in America: Women’s voices. New York, NY: Springer; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koblin BA, Metch B, Novak RM, Morgan C, Lucy D, Dunbar D, et al. Feasibility of identifying a cohort of US women at high risk for HIV infection for HIV vaccine efficacy trials: Longitudinal results of HVTN 906. J Acquir Immune Deficiency Syndr. 2013;63(2):239–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown-Peterside P, Chiasson MA, Ren L, Koblin BA. Involving women in HIV vaccine efficacy trials: Lessons learned from a vaccine preparedness study in New York City. J Urban Health. 2000;77(3):425–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown-Peterside P, Rivera E, Lucy D, et al. Retaining hard-to-reach women in HIV prevention and vaccine trials: Project ACHIEVE. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(9):1377–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. JAMA. 2007;297(4):407–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Concannon TW, Meissner P, Grunbaum JA, McElwee N, Guise JM, Santa J, et al. A new taxonomy for stakeholder engagement in patient-centered outcomes research. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(8):985–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tindana PO, Singh JA, Tracy CS, et al. Grand challenges in global health: Community engagement in research in developing countries. PLoS Med. 2007;4(9):e273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]