Abstract

Background and Objectives

The self-reported health of foreign-born older adults (FBOAs) is lower than that of nonimmigrant peers. Physical activity (PA) and mobility enhance health in older age, yet we know very little about the PA and mobility of FBOAs. In this analysis we sought to determine: (a) What factors facilitate PA amongst FBOAs? and (b) How do gender, culture, and personal biography affect participants’ PA and mobility?

Research Design and Methods

We worked closely with community partners to conduct a mixed-method study in Vancouver, Canada. Eighteen visible minority FBOAs completed an in-depth interview in English, Cantonese, Mandarin, Punjabi, or Hindi.

Results

Three dominant factors promote participants’ PA and mobility: (a) participants walk for well-being and socialization; (b) participants have access to a supportive social environment, which includes culturally familiar and linguistically accessible shops and services; and (c) gender and personal biography, including work history and a desire for independence, affect their PA and mobility behaviors.

Discussion and Implications

We extend the Webber et al. mobility framework, with examples that further articulate the role of gender (e.g., domestic work), culture (cultural familiarity) and personal biography (work history and a desire for familial independence) (Webber, S. C., Porter, M. M., & Menec, V. H. (2010). Mobility in older adults: A comprehensive framework. The Gerontologist, 50, 443–450. doi:10.1093/geront/gnq013). Future programming to support the PA of FBOAs should be culturally familiar and linguistically accessible.

Keywords: Immigration, Health, Qualitative

Physical activity (PA), the movement of one’s body (World Health Organization [WHO], 2015), and mobility, moving one’s body through space using a variety of modes (Webber, Porter, & Menec, 2010), allow older adults to participate in their communities (Gardner, 2011), cultivate social connections (Kohn, Belza, Petrescu-Prahova, & Miyawaki, 2016), actively participate to maintain their health (Hirvensalo, Rantanen, & Heikkinen, 2000), and access services and resources (van Cauwenberg et al., 2011). PA and mobility play a vital role in supporting community-dwelling older adults who overwhelmingly wish to “age in place” (Wiles, Leibing, Guberman, Reeve, & Allen, 2012). A supportive neighborhood context is crucial for the well-being of older adults, in particular if health challenges, financial limitations, or driving cessation impede their ability to travel outside their immediate area (Gardner, 2011). Cross-sectional studies demonstrate a strong association between the design of the local built environment and mobility, health, and PA levels of residents (Saelens & Handy, 2008). When examining the mobility and PA of older adults, we must consider both the social and built environments.

The self-reported health of visible minority and foreign-born older adults (FBOAs) is poor compared with their nonimmigrant peers (Ng, Lai, Rudner, & Orpana, 2012). In Canada, where our study was conducted, the term visible minority refers to persons who are non-Caucasian in race or non-White in color, and not aboriginal (Statistics Canada, 2012). In a systematic review of neighborhood environment and the health of older adults, the authors concluded the following: “Aging research has documented various racial/ethnic and socio-economic disparities in health among older adults . … It is valuable to do more studies with racially/ethnically diverse communities.” (Yen, Michael, & Perdue, 2009, p.460). With a focus on the mobility and PA of visible minority FBOAs, this study contributes to filling this identified gap in the literature.

Theoretical Framework

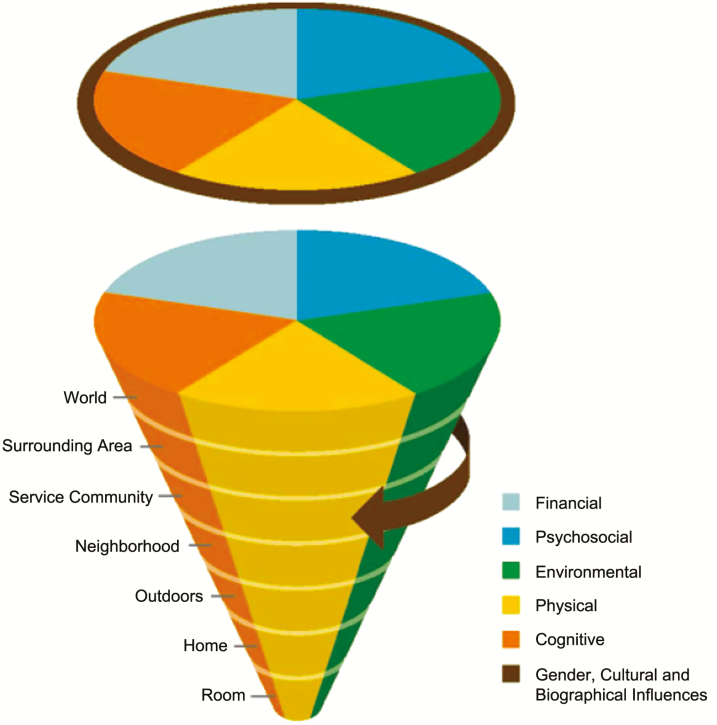

Our study adopts a socioecological perspective rooted in the understanding that individuals and their health-related behaviors cannot be divorced from the context and environments in which they live (Lawton, 1982). Our findings extend the socioecological model put forth by Webber and colleagues (2010), in Figure 1. This model offers a comprehensive and interdisciplinary approach to understanding mobility in older adults.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework for mobility in older adults (Webber et al., 2010).

Prior to the introduction of the Webber model, and even still, mobility literature has tended to focus on one aspect of mobility (e.g., neighborhood walkability, physical function and limitations, driving cessation) or one environment (e.g., the home, neighborhood, city infrastructure; Umstattd Meyer, Janke, & Beaujean, 2014; Webber et al., 2010). The Webber model urges researchers to take a more comprehensive and interdisciplinary approach to mobility.

The Webber model is comprised three components: first, the concentric life spaces (represented in a cone format); second, the key determinants of mobility (financial, psychosocial, environmental, physical, and cognitive) are represented as wedges of the cone; and finally, the outermost ring encircling the entire cone represents the crosscutting influence that gender, culture, and biography have on mobility. The life spaces, ranging from the home to the world are presented in a cone. Within the home the mobility determinants are presumed to have less of an influence, whereas the farther one travels from home, the greater the influence; these relationships are presented visually with the determinants being smaller within the home, at the bottom of the cone, and much larger within the surrounding area and world, at the top of the cone (Webber et al., 2010). Although presented separately with distinct colors, the mobility determinants are assumed to be overlapping and intersecting. The three crosscutting factors, gender, culture, and biography, are hypothesized as influencing all mobility determinants, hence their placement on the outside of the cone. As Webber and colleagues (2010) argued, “gender, culture, and biography (personal life history) each fundamentally shapes individuals’ experiences, opportunities, and behaviors and therefore acts as crosscutting influences on mobility” (p.446). Gender is included because women are at a greater risk for disabilities and limitations affecting their mobility. Although the term gender is not specific to the experiences of women—gender refers to both sexes—the examples provided by the authors focus on the mobility of women, specifically the mobility limitations that women experience. Culture is included because it may affect social networks and relationships, opportunities earlier in the “life course” (e.g., education or employment), and PA practices and norms.

Although efforts were made to conceptually link the older person, their environments, and health and well-being, the outermost ring of the Webber model is presently underdeveloped. This ring, representing gender, culture, and biography is believed to “exert influence on all of the mobility determinants” (Webber et al., 2010, p.446). As such it must be more fully examined. Researchers are just beginning to tease apart exactly how, and under what circumstances these three, intersecting influences affect the mobility and PA levels of older adults (e.g., Pruchno, Wilson-Genderson, & Cartwright, 2012; Umstattd Meyer et al., 2014). For example, in one application of the model to data from 6,112 older adults, age and marital status, both markers of personal biography, predicted personal and community mobility (Umstattd Meyer et al. 2014). The present analysis will contribute to a deeper understanding of the outermost ring and identify which mobility determinants are most salient for this underresearched sample of FBOAs.

Research Questions

Elsewhere (Tong, Sims-Gould, & McKay, 2018), we reported that FBOAs in our study engaged in adequate levels of PA, taking 7,876 steps per day, on average. Healthy older adults should acquire approximately 7,000–10,000 steps per day (Tudor-Locke et al., 2011). Here we address the following questions: (a). What factors facilitate levels of PA in FBOAS?, and (b) Guided by the Webber and colleagues (2010) theoretical model, how do gender, culture, and personal biography affect participants’ mobility?

Methods

The analysis presented here is part of a larger ethnographic study (Active Streets Active People: Foreign-Born; ASAP-FB) that aimed to characterize the PA habits of multilingual and non-English speaking FBOAs who reside in South Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada (N = 49). In the larger, descriptive study, 49 participants completed surveys on their health, mobility, PA, and neighborhood perceptions. They also wore an accelerometer and GPS (global positioning system) unit for 1 week, measuring the intensity and location of their activity. Here we focus on data generated through in-depth seated interviews (n = 18), which took place approximately 1 month after the survey sessions and monitor wear.

Setting and Context

The South Vancouver neighborhood is home to approximately 16,000 older adults and is linguistically diverse; more than half of residents speak a language other than the official languages of Canada, English, and French (Statistics Canada, 2012). The area is relatively well-served by public transit, with a Transit Score of 61/100 and is classified as “somewhat walkable” with a Walk Score of 63/100 (Walk Score, 2016). Transit and Walk Scores (www.walkscore.com) are calculated using a patented method, which has been validated and is free to the public, based on postal code (Walk Score, 2018).

Sample and Recruitment

Our long-standing partnership (see, Tong, Franke, Larcombe, & Sims-Gould, 2017) with staff and volunteers at South Vancouver Neighborhood House (SVNH) enabled us to access a diverse group of FBOAs. Neighborhood houses are nonprofit organizations that deliver a range of community programs for all ages. The Seniors Hub Council (SHC) at SVNH assisted with development and implementation of our study. Eight peer volunteers from SHC gathered names and contact information for 113 individuals who expressed interest in participating in our study. We placed posters and brochures in SVNH and community centers. SHC volunteers, who were not compensated, endorsed, and promoted our study within their respective ethnocultural communities. SHC volunteers verbally promoted the study, and collected names and contact information at community centers, exercise and dance classes, ethno-specific group activities, English as a Second Language (ESL) classes, and places of worship. Multilingual research assistants telephoned 113 individuals and recruited 49 participants. Of these 49 participants who completed the first wave of ASAP-FB, 47 agreed to be contacted for an in-depth follow-up interview. Our target was approximately 20 interviews. In our prior work (e.g., Franke , Tong, Ashe, McKay, & Sims-Gould, 2013), we found that approximately 20 interviews allowed us to reach data saturation (Morse, 1995) on the topic of mobility and PA. We recruited 18 participants from this group of 47, on a first-come basis, to complete the interviews. With these 18 interviews, we reached data saturation with women participants, but did not with men, of which there were very few in the larger ASAP-FB study. Participant characteristics and self-reported health are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Sample (n = 18) | Sample (n = 18) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | ||

| Gender | Highest level of education | ||

| Women | 14 (77.8) | Primary | 3 (16.7) |

| Men | 4 (22.2) | Some secondary | 6 (33.3) |

| Completed secondary | 2 (11.1) | ||

| Some/completed technical school | 3 (16.7) | ||

| Some/completed university | 2 (11.1) | ||

| Graduate degree | 1* (5.5) | ||

| Age—mean no. of years | 72.56 (SD: 4.81) Min: 66, Max: 81 |

Total no. of comorbidities—mean | 2.78 (SD: 2.34) Min: 0, Max: 10 |

| Marital status | Home ownership | ||

| Married | 10 (55.6) | Own | 13 (72.2) |

| Widowed | 6 (33.3) | Live in home owned by family | 2 (11.1) |

| Separated or divorced | 2 (11.1) | Rent | 3 (16.7) |

| Living arrangement | Use of mobility aids | ||

| With spouse/partner | 8 (44.5) | Yes | 7 (38.9) |

| Multigenerational household | 4 (22.2) | No | 11 (61.1) |

| Alone | 6 (33.3) | ||

| County of birth | Possess valid driver’s license | ||

| China | 8 (44.5) | Yes | 6 (33.3) |

| India | 7 (38.9) | No | 12 (66.7) |

| Pakistan | 2 (11.1) | ||

| Fiji | 1 (5.5) | ||

| Vietnam | 0 | ||

| Ethnicity | Possess public transit pass | ||

| Chinese | 8 (44.5) | Yes | 13 (72.2) |

| South Asian | 10 (55.5) | No | 5 (27.8%) |

| Years in Canada—mean | 31.61 (SD: 14.07) Min: 11, Max: 55 |

BMI—mean | 27.96 (SD: 5.71) Min: 20.3, Max: 39.3 |

Note: BMI: body mass index.

*1 participant did not report education.

Eligible participants were aged more than 65 years, resided in the South Vancouver catchment, self-identified as foreign-born visible minority, and reported leaving the home at least once a week. All study documents were professionally translated in the abovementioned five languages. We used professional interpreters and multilingual research assistants for data collection.

Data Collection and Analysis

This study received approval from the University of British Columbia Behavioral Research Ethics Board. Data collection took place during May–June, 2013.

In-depth interviews

We completed in-depth interviews at a private location chosen by participants, either in their home or in a community center room. CT conducted 15 interviews with the aid of a professional interpreter. Three participants completed their interview with CT in English, at their request. Interpreters used consecutive translation (Gile, 2001), in which the interpreter allows the participant to speak, then the participant pauses while their words are restated in English by the interpreter.

A semi-structured interview guide was used to inquire about daily routines and PA patterns. We include sample interview questions in Table 2. Interviews averaged 57 min in length (min: 27, max: 100). Interviews were digitally recorded and professionally transcribed. Interview participants were given an honorarium in recognition of their time (a $20 CAD gift card to a local grocery store or pharmacy).

Table 2.

Linking the Interview Questions, a Prior Coding and Final Coding to the Webber Model Domains

| Webber domains | Interview questions, linked to and informed by Webber domains | A priori and initial codes, informed by Webber model and first reading of transcripts | Final, most salient codes and themes, based on line-by-line coding and team analysis meetings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mobility determinants: “Wedges of the cone” * Physical Psychosocial Environmental Financial |

What gets you moving your body? Prompt for time, place, with whom What prevents you from moving your body? Prompt for barriers: cost; access; pain; physical ability, etc. If city planners could change one thing about your neighborhood, what would it be? Do you think that your neighborhood is walkable? Why/why not? Can you tell me about the transit system in your neighborhood? Prompt for cost; subsidized passes; use of transit. |

Facilitators to PA and mobility: - Desire to maintain health - Friendships and social connections - Shops and services in neighborhood - Transit provides access Barriers to PA and mobility: - Pain - Domestic work - Enviro barriers - Cost |

Walking for well-being Socializing with peers Same-language and culturally familiar activities Reliance on transit; gendered transportation; transit affords independence |

| Life spaces Home –> world |

Please describe a typical day? A typical week? Prompts: where do you go? What do you do? Who do you see? How do you get there? | Room/Home Neighborhood Surrounding area Service community Surrounding area World |

Home Community centers Neighborhood house |

| Outermost ring: | (In addition to above questions) | ||

| Gender Biography Culture |

How would you rate your ability to communicate in English? Prompt for: communication difficulties; situations where they are able to use their first language, etc. | Communication difficulties; same-language activities | Same-language activities |

| Do you think that (insert ethnocultural group here) people have physical activity habits that are unique? Do you think that you are more/less active than older, Caucasian Canadians? Why? | Cultural differences? | ||

| What gets you moving your body? Tell me about your typical day/week. (from above) | Housework Domestic Work Walking not driving |

Gendered work Gendered transportation |

|

| Independence | A desire for independence and self- reliance |

Note: PA = physical activity.

*Note that we did not include cognition in our model, one of the “wedges” in the Webber model. One of the exclusion criteria for the Active Streets Active People: Foreign-Born study was a diagnosis of significant cognitive impairment.

Qualitative analysis and strategies for rigor

Transcripts were assigned pseudonyms, anonymized, and entered into NVivo 10, a qualitative analysis program. Concepts from the Webber model guided our initial coding structure (see Table 2). We also used open coding, allowing for classification of elements that emerged beyond the concepts highlighted in the Webber model. The coding process included the following: (a) CT and JSG independently engaged in initial coding of the first five transcripts; (b) through team meetings and reviewing text segments and nodes, all authors refined the coding structure; and (c) CT then engaged in line-by-line coding of the 18 transcripts. Throughout data collection and the initial analysis process, the authors and multilingual research assistants met regularly to review the coding structure, salient themes and to discuss any discrepancies. Strategies for rigor included reflexive memoing, team analysis meetings, and sharing preliminary findings with the SHC.

Results

We identified three dominant factors that promoted the PA and mobility of FBOAs in South Vancouver. These factors are the following: (a) walking for well-being and socialization; (b) access to a supportive social environment, which includes culturally familiar and linguistically accessible shops and services; and (c) gender and personal biography, including work history and a desire for independence, affect participants’ PA and mobility behaviors. For each factor we have identified in brackets the most closely related domains from the Webber model. Characteristics for quoted participants are in Table 3, at the end of this results section.

Table 3.

Biographical and Physical Activity Information for Participants Quoted in Results

| Participant pseudonym | Participant information |

|---|---|

| Raveena | 67-year-old woman, South Asian, widowed, uses a cane |

| Mrs. Shum | 67-year-old woman, Chinese, married, no mobility aid |

| Mrs. Lam | 71-year-old woman, Chinese, married, no mobility aid |

| Mukundi | 66-year-old woman, South Asian, widowed, no mobility aid |

| Jasmeet | 78-year-old woman, South Asian, widowed, uses a cane and walker |

| Amita | 78-year-old woman, South Asian, married, no mobility aid |

| Man-Yee | 77-year-old woman, Chinese, married, no mobility aid |

| Ka-Lee | 81-year-old woman, Chinese, widowed, no mobility aid |

| Mr. Shum | 71-year-old man, Chinese, married, uses a cane |

| Mr. Lam | 73-year-old man, Chinese, married, no mobility aid |

| Manpreet | 70-year-old woman, South Asian, widowed, no mobility aid |

| Simrita | 66-year-old woman, South Asian, widowed, no mobility aid |

| Vivian | 76-year-old woman, Chinese, widowed, uses a cane and walker |

Factor 1: “I Want to Happy Myself”: Walking for Well-being (Physical and Psychosocial)

The most common form of PA that participants described was walking around their neighborhoods, either for errands or explicitly for exercise. The first factor promoting mobility and PA was walking for their well-being, and the satisfaction derived from walking both for health and social reasons. Raveena explained why she enjoys her neighborhood strolls:

Oh, I’m going for the fresh air and I want to meet the peoples and I want to make my feelings better … I like the flowers and trees and weather. And I want to happy myself, you know … It’s good. And it’s good because, you walk and your heart will be strong and your brain. Then you get thinking about that … the brain is fresh all the time when you go out. If you sit there at home, you are sleeping and you will be lazy.

This quote from Raveena aptly summarized one of the most salient factors motivating participants to move their bodies: participants described both the mental and physical benefits, an overall sense of well-being that comes from getting outside and being active. Participants listed a range of benefits associated with their neighborhood walks: keeping the heart strong, keeping the brain fit, reducing stress, raising their spirits, maintaining their weight, and preventing disease.

In Raveena’s first quote, she also noted, “I want to meet the peoples,” and she went on to explain that she enjoys chatting with the 90-year-old Chinese widow who lives across the street and takes pleasure in hearing the laughter of children playing at the nearby playground. In addition to the physical benefits, participants described the psychosocial benefits of getting out to see others on their walks, be it passersby, neighbors, or friends with whom they walk. Psychosocial benefits included the following: feeling more positive and uplifted when walking with friends; feeling “happy” to observe nature (trees, gardens, wildlife, etc.); feeling connected to strangers who simply say “hello” as they walk by; and feeling connected to familiar faces in the neighborhood. Walking itself was also considered more pleasant with company. Mrs. and Mr. Lam complete most of their errands on foot, together (See Figure 2). Mrs. Lam shared, “walking with a friend allows you to go farther.” Mukundi does regular afternoon walks with a friend who lives nearby, in addition to a longer Sunday walk with another friend after they attend temple. She explained the psychosocial and physical benefits of walking with others:

Figure 2.

Photograph of Mr and Mrs Lam walking from the local community center to their home (source: community observations, photo release obtained).

I feel stressed sometimes. But when I go out meet people, I forget about it. Talking to someone about here or India relaxes the mind … So walking alone, I don’t want to walk too long, I’m quiet. With friend it’s—we are chatting and we—I don’t even realize we’ve gone so far. That’s how it happened, there’s the difference.

In this quote, Mukundi describes how walking with others not only relaxes her mind and reduces her stress (a psychosocial benefit), but also allows her to walk farther and longer (physical benefits).

The role of walking for participants was multifaceted. It included walking for well-being and health, but was often accompanied by a sense of joy, and aspects of socialization and companionship. This shows us that walking is more than just a form of PA to promote health. It is also a form of socialization, a means to connect with the community.

Factor 2: “These Few Blocks, These Are My Village”: A Supportive Social Environment (Psychosocial, Environment, and Culture)

When we asked Jasmeet what she liked best about her neighborhood, she explained:

These few blocks, these are my village. Because I know those people. [The] bus is near. And my temple is near. [When] I’m not feeling good I go there. And on Sunday I go and volunteer there . … When we bought this house, we thought the gurdwara (temple) should be near—every weekend we should go.

This quote from Jasmeet demonstrates how a supportive social environment consists of the psychosocial domain (“knowing people,” having a place to volunteer and connect), the environmental domain (“the bus is near,” “temple is near”), and the cultural (a culturally familiar place of worship, where her first language, Punjabi, is spoken). Jasmeet’s summary of her neighborhood is also an example of what many of the participants told us. They get out the door and engage with their local community because they have access to activities, shops, services, and social or religious gatherings that are culturally familiar. The main factor that appears to be getting participants “out the door” is culturally familiar activities. Cultural familiarity can be derived from objects, activities, songs, dances, foods, clothing, etc. that provide older immigrants with a sense of belonging and promote both physical and psychological comfort (Son & Kim, 2006). Participants repeatedly cited getting out the door for culturally familiar shops (e.g., the local Punjab—South Asian—market and mini Chinatown), restaurants, religious and social gatherings. All South Asian women who participated in our interviews attend wellness groups at three local community centers. These wellness groups are facilitated by the centers and are peer led—by FBOA women, for FBOA women.

Amita described her Monday morning wellness group, which primarily consists of older South Asian women:

They make the tea and everybody do something, any song, any stories, what happen there. They tell stories or sometimes sing songs. Functions for Mother’s Day. We celebrate the Diwali there and Vaisakhi. [The interpreter added, these are festivals. Indian festivals that they celebrate there.]

Participants also engaged in culturally familiar physical activities. The majority of our Chinese participants reported regularly doing Tai Chi, Qigong/Shigong and/or Luk Tung Kuen, all forms of traditional Chinese exercise (TCE; Shen, Lee, Lam, & Schooling, 2016). TCE classes are also facilitated by local service agencies but led by peer volunteers. The wellness groups and TCE classes are no cost or low cost, and crucially, they are accessible: they are close by and readily accessible to participants by transit or walking. This coupling of culturally familiar activities (the cultural domain), and proximity and accessibly (the environmental domain), is what facilitates participation and PA in this sample of FBOAs.

An added benefit of these culturally familiar activities, shops, and services is that they are typically linguistically accessible. Linguistic accessibility (Agrawal, Qadeer, & Prasad, 2007) means individuals can engage in community activities or access services in the language of their choosing, be it through formal translation, ad hoc peer interpretation, or if it is offered in their first language. Ka-Lee, who has voluntarily run a Luk Tung Kuen class, in Cantonese, for more than 20 years, stated:

According to my experience that’s [have an active life without speaking English] doable. That’s why I also encourage people, I say, look at me, I don’t even speak English but I can still be active and do the volunteer work and you can speak different languages. You can also do that, too. And I’m also volunteering for Red Cross right now.

Most of the wellness groups, TCE classes, and social gatherings that participants attend are conducted in a language other than English. Linguistic accessibility is crucial for this sample. All participants reported speaking a language other than English in the home. As reported in Tong and colleagues (2018), participants’ English skills were not strong, with nearly two thirds reporting difficulties in comprehension, speaking, and reading. Participants were getting out of their homes, moving their bodies, and engaging with a local environment that is linguistically accessible and culturally familiar.

Factor 3: The Impact of Gendered Identity and Personal Biography on Mobility and PA (Gender, Biography, Environment, and Culture)

Webber and colleagues (2010) posited that gender, culture, and personal biography affect the mobility of community-dwelling older adults. In addition to cultural familiarity, as described earlier, we found gender and personal biography to be salient themes. First, we discuss the aspect of gender, and then we discuss themes related to personal biographies.

“He can’t drive me everywhere”: transportation (gender and environment)

For participants, gender may have affected their PA and mobility both inside the home and around the neighborhood. Most participants (14 of 18 interviewees) were women. Therefore, for this analysis, we focused on women and their experiences of mobility and PA. The four men in this sample had very diverse PA and mobility patterns, which precluded us from identifying transportation themes central to the experiences of FBOA men.

Out-of-home mobility is largely affected by the fact that only two women currently had a driver’s license, and many reported never having driven. Ka-Lee would like more activities at the community center closest to her home because she does not drive. Her husband drives but, she explained, “he can’t drive me everywhere … it’s too much for the old man, over 80 years. If [activities] were here then I would have the freedom to come anytime.” Although a few participants reported getting rides from their spouse or children, most relied on walking and public transit for their daily outings.

“I can’t go [walking] every day … first I want to finish the work at home”: domestic work (gender, environment, and culture).

In addition to transportation, participants also spoke of their experiences of “women’s work” and “family work” (Thompson, 1991) in the home, including the following: housework; cooking for large, multigenerational households; and gardening. Participants’ homes were immaculate, and when asked who did the cleaning, women participants often described an entire weekday spent deep cleaning their homes. The participants did not explicitly refer to domestic work and meal preparation as “women’s work” or articulate gender norms, but in our discussions it was clear that women of all ages, including participants, their adult daughters and granddaughters, were the ones tasked with these chores. In the following exchange, Amita described how housework takes priority over more formal exercise:

I make the vegetable for night dinner and clean the kitchen and here, hall and everything. Once a week I vacuum. Two, three days after [vacuuming] I do the washing clothes, laundry … She [doctor] said go for a walk and—walking is good for seniors. Every day. I can’t go every day … First I want to finish the work at home.

Ten interviewees showed us their impressive gardens, which often included ingredients used in Chinese and South Asian cooking. For example, Jasmeet grows and dries many herbs used in Indian cooking. Here we see the intersection of the cultural and environmental domains, with yards and gardening space allowing participants to grow foods and herbs that they use in recipes from their countries of origin. Aside from gardening and yard maintenance, the household work seemed largely to be the domain of the women we interviewed.

“In Fiji I would work in the farm … ”: personal biography (biography and environment)

A participant’s personal biography often influenced why they wanted to go out of their homes and be mobile. These active participants with a history of PA through their life course, either through their own work or through helping family members, tended to remain active as they aged. When we asked Manpreet what motivated her to leave the home, to get out for short walks, she brought up the role of PA in her work history: “The fresh air. When I stay inside, I don’t get so much fresh air. And in Fiji I would work in the farm, taking care of cows, or doing gardening, taking care of vegetables.” For many participants, a lifelong history of outdoor work, farming, and moving their bodies compelled them to continue seeking opportunities to be active and outdoors in retirement. For these participants, an intersection of the outdoor environment and personal biography has led to mobility and PA in later life. Participants also described a life course of PA, through their hobbies and active lifestyles. Running, hiking around the mountains of Hong Kong, walking to work, and walking children to school were often mentioned.

Underlying this continuation of being active throughout the life course is often the desire to remain independent. When we asked participants what motivated them to keep active, many expressed a desire to stay active, and therefore healthy, in order to maintain their independence. Underlying this continuation of being active throughout the life course if often the desire to remain independent. Simrita explained:

[I take the] bus when I go to Fraser. When I go to any other place I go to by bus. I don’t take ride. I don’t disturb my kids to give me ride. I’m okay to go anywhere. … It’s so easy. It’s so easy to travel in the bus, SkyTrain. I love it.

Here, Simrita’s independence (related to the biographical domain) is facilitated by the environmental domain, and the presence of an accessible transit system.

Discussion and Implications

Our findings extend the scant literature that seeks to better understand factors that promote or inhibit PA and mobility of immigrants. Our analysis highlights themes specific to the immigrant experience, as well as those applicable to different groups of older adults, irrespective of their provenance. Participants walked for well-being and were motivated by social engagements to get out and be active. This finding is consistent with the broader PA literature that focuses on native-born older adults. Indeed, friendships, human interactions, and engagement with the local social environment (see Figure 3) promote PA and the mobility of community-dwelling older adults regardless of culture (e.g., Gardner, 2011). Similarly, older adults who had active youths tended to continue this into older age. This is consistent with continuity theory (Atchley, 1989), which posits that older adults extend life patterns and activities from middle age into older age, and this continuity reinforces their life satisfaction and personal fulfillment. At the outset of this research, we expected to find differences rather than commonalities. Consistent with the broader body of research on minority and immigrant older adults (e.g., Garcia, Garcia, Chiu, Rivera, & Raji, 2018; Forrester, Gallo, Whitfield, & Thorpe, 2018), we too expected to focus on differences and deficits (Koehn, Neysmith, Kobayashi, & Khamisa, 2013), rather than commonalities and positive health behaviors. The fact that some of the most salient themes regarding the activity and mobility of FBOAs are like those of the nonimmigrant older adult population is in itself an important finding. Ultimately, older adults across genders, cultures, and geographies want to stay active and mobile to maintain their independence and health (Schwanen & Ziegler, 2011).

Figure 3.

Photograph of community members attending an event at South Vancouver Neighborhood House (source: community observations, photo release obtained).

Extending the Webber Framework With Data-Driven Examples

Our analysis articulates some of the ways that “gender, cultural, and biographical influences” affect mobility and PA. Our analysis does not intend to alter the Webber model, rather it is an empirical application of the model to an understudied population of FBOAs.

Culture

In the Webber model, culture is not defined. Scholars have increasingly questioned the overreliance on culture, and acculturation, as key explanatory variables in immigrant health research (Koehn et al., 2013). Notwithstanding, culture is still perceived as a significant driver of health behaviors (Napier et al., 2014).

In our analysis, it was clear that cultural familiarity (Son & Kim, 2006), a very specific concept, and linguistic accessibility, a factor more closely related to immigration trajectories than culture, were more salient. At the very least they were more clearly articulated than cultural norms or beliefs regarding health, PA, and the aging body. The impact of culture on participants’ mobility was difficult to disentangle from other issues of age, immigration status, linguistic abilities, health issues and health awareness, personal PA habits, etc. In this sense, details related to an individual’s personal biography and gender seemed to be more relevant than their culture, per se. The Webber model is correct to present these three crosscutting factors together, as one arrow encircling the model, as these are deeply intertwined and empirically challenging to disentangle.

Personal biography

Age and marital status, both markers of personal biography, affect the mobility of older adults (e.g., Umstattd Meyer et al., 2014). Our study highlights two additional features of participants’ personal biographies that drive mobility: a lifetime of moving the body and a desire for independence. Consistent with research with nonimmigrant older adults (e.g, Franke et al., 2013), many participants described a life course of PA and moving the body, which persisted in older age. Research on older Asian immigrants shattered the persistent notion that older adults rely on children’s filial piety, co-family dwelling, and the “myth of shared care” (Chiu & Yu, 2001) in their later years. We too found that many participants overwhelmingly desired independence from their families and saw PA and community mobility as a means to maintain health and independence as they age.

Gender

Older women tend to experience limited personal mobility as a consequence of not driving (Siren & Hakamies-Blomqvist, 2006), and this was true of the FBOA women in our sample. Women in our study relied on public transportation and walking to move around the community. Participants did not discuss the built environment, even when explicitly probed. The exception to this trend was public transit, a feature of the local built environment that was most clearly associated with participants’ PA and mobility outside the home. For the women in our sample, most of whom do not drive, it appears that the local environment (environment determinant, including public transit and local walkability) and the neighborhood and service community (life spaces) take on a greater role in their mobility patterns. In this sense, we would propose that these “wedges” and “layers” of the Webber cone expand and contract, perhaps resembling a waffle cone rather than a smooth-edged cone. Certain environments and life spaces take on greater importance when gendered norms dictate transportation habits and options.

Gendered domestic work also increased participants’ daily and weekly PA patterns, especially hours dedicated to cleaning and cooking. The literature suggests that gendered and culturally informed norms, coupled with the immigration experience, lead to more domestic work amongst foreign-born women. Previous Canadian research has confirmed that gendered norms and patriarchal structures within the South Asian community, which tend to persist after migration, dictate that women are charged with virtually all the indoor domestic labor (George & Ramkissoon, 1998). Chinese women experience a transition away from paid work and toward the domestic sphere after international migration: Ho (2009) argues that a “feminization” of domestic work occurs as families and individuals renegotiate work and care roles in their new country. Although this facilitates PA in our sample, a potentially negative aspect of this gendered work within the home is that it may limit women’s opportunities and time to more fully participate in the community (Koehn, Habib, & Bukhari, 2016). Here we confirm the Webber model’s overall conical design encircled by “gender, culture, and biography”: When gendered norms coupled with the immigration experience push and/or keep women working in the domestic sphere, their mobility may be limited to the smaller portions of the cone, the room, and home life spaces.

Limitations

Our recruitment was limited to those individuals who were connected enough with the community to know about the study, and who had the time and ability to participate. FBOAs can be a difficult-to-access population. The SHC worked for 2 months to obtain the contact of information of potential participants in a range of settings and programs (e.g., places of worship, ESL classes); however, when recruiting from wellness groups and community centers, we acknowledge that this sample may be biased toward those who are in their communities and actively maintaining their health. Future studies, working in concert with community-based outreach organizations, should endeavor to recruit individuals who are less active or homebound. Also, seasonal variation is not captured in our analysis. We chose to complete data collection during the spring months, to enhance participation and safety. Finally, as noted earlier, we did not sufficiently capture the experiences of foreign-born older men.

Implications for Future Research, Policy and Programming

Future research would be strengthened with a comparative study, more specifically focused on the experiences of foreign-born older men and women. We were unable to fully explore mobility and PA with the older men in this sample, although our larger study (N = 49) confirms that FBOA men are less physically active and more likely to drive (Tong et al., 2018). We would also encourage future researchers to examine the notion that cultural norms dictate PA habits. In our experience, participants found it difficult to articulate if and/or how cultural norms influence their activity and mobility. At the outset of this study, we anticipated to find differences between the two cultural groups (Chinese and South Asian). However, in our analysis the most salient themes were indeed quite similar: walking for wellness was the most common PA for both groups. Although the Chinese older adults attended TCE classes and the South Asian older adults attended South Asian wellness groups, their motivations were similar: enhancing their health in a social setting, with same-language peers. Future research should further probe and question the role of culture, not just cultural familiarity, as it pertains to the activity and mobility of FBOAs.

With respect to the Webber model, our application generally confirms the overall design and the intersecting relationships within the model. We do propose that gender and cultural norms, which encircle the model as crosscutting factors, may cause certain life spaces and mobility determinants to expand or contract, creating a “waffle cone” rather than a smooth-edged cone. For example, when women do not drive, some life spaces (e.g., the neighborhood, service community) and the environmental wedge (including transit) take on a greater role in their individual mobility. Future studies should more explicitly probe the role of gender as it affects the mobility and PA of FBOA women and men. This study also raises the question: do the gender and cultural norms encapsulated in the outermost ring have a more prominent role for individuals who are part of a minority group?; for individuals who have gender and cultural norms that are distinct from that of the majority population?; for individuals who do not speak the dominant language? Our findings suggest that they do.

The Webber model also helped us to identify the multifaceted nature of a “supportive social environment.” A supportive social environment for FBOAs is one that is relatively well-served by public transit and walkable (environment) and provides opportunities for friendships and connections to flourish (psychosocial) in a context that is linguistically accessible and culturally familiar (biography and/or culture). Our research is consistent with the built environment literature (Rosso, Auchincloss, & Michael, 2011) and “age-friendly cities” initiative (Buffel, Phillipson, & Scharf, 2012; Plouffe & Kalache, 2010), which argue that as the global population ages, cities must invest in both built and social environments that support older adults. With respect to FBOAs, our research highlights the need for neighborhoods that offer culturally familiar and linguistically accessible shops, services, and activities. Many global cities, Vancouver included, are home to ethnic enclaves and neighborhoods that provide such services (e.g., Chinatowns, Punjab Markets, etc.). City planners must be mindful of creating policies to protect the character and diversity of these neighborhoods, to support the health and well-being of FBOAs who reside there. Finally, the provision of linguistically accessible community programming needs to be systematized (Agrawal et al., 2007). At present, it often falls on volunteers, peers, and frontline staff to provide ad hoc interpretation (Agrawal et al., 2007). As the aging population grows and becomes more diverse (Statistics Canada, 2012), there will be an increased need for multilingual seniors’ services.

Conclusion

A nascent body of literature suggests that FBOAs experience their local neighborhoods in ways that are distinct and not well understood (e.g., Bird et al., 2009; Brown et al., 2009; Mathews et al., 2010). Our analysis provides a deeper level of understanding. FBOAs in our sample rely on neighborhoods that are moderately served by public transit and provide activities and services that are culturally familiar and linguistically accessible.

Like many higher-income countries, the Canadian older adult population is projected to become increasingly diverse in coming decades, with 26% of older adults identifying as a visible minority by 2032, and 44% by 2062 (Carrière, Martel, Légaré, & Picard, 2016). As FBOA and visible minority older populations continue to grow, communities will need to invest in and support physical and social activities that are culturally familiar and linguistically accessible. It behooves us to be mindful of the distinct need and opportunities that arise from questions of gender, personal biography, and family context. We caution scholars and practitioners to not equate foreign-born and minority status with deficits. In our cohort, when provided a supportive neighborhood context and accessible environment, participants acquired sufficient PA and meaningfully engaged with their communities while contributing to the broader social fabric.

Funding

Funding for this research was provided by the Vancouver Foundation (Grant ID: 20R07558). Catherine Tong’s doctoral research was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Frederick Banting & Charles Best Doctoral Award and the University of British Columbia’s Four Year Fellowship. Dr Sims-Gould is a CIHR New Investigator and a Micheal Smith Foundation for Health Research Scholar.

Conflict of Interest

None reported.

References

- Agrawal S. K., Qadeer M., & Prasad A. (2007, Fall). Immigrants’ needs and public service provision in Peel region. Our Diverse Cities, 4, 108–112. Retrieved from: http://www.metropolis.net/pdfs/ODC%20Ontario%20Eng.pdf#page=110 [Google Scholar]

- Atchley R. C. (1989). A continuity theory of normal aging. The Gerontologist, 29, 183–190. doi:10.1093/geront/29.2.183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird S., Radermacher H., Feldman S., Sims J., Kurowski W., Browning C., & Thomas S (2009). Factors influencing the physical activity levels of older people from culturally-diverse communities: An Australian experience. Ageing and Society, 29(08), 1275–1294. doi:10.1017/S0144686X09008617 [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. C., Mason C. A., Lombard J. L., Martinez F., Plater-Zyberk E., Spokane A. R., … Szapocznik J (2009). The relationship of built environment to perceived social support and psychological distress in Hispanic elders: The role of “eyes on the street”. Journal of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 64, 234–246. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbn011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffel T., Phillipson C., Scharf T (2012). Ageing in urban environments: Developing “age-friendly cities”. Critical Social Policy, 32(4), 597–617. doi:10.1177/0261018311430457 [Google Scholar]

- Carrière Y., Martel L., Légaré J., & Picard J (2016). The contribution of immigration to the size and ethnocultural diversity of future cohorts of seniors. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/75-006-x/2016001/article/14345-eng.pdf?st=KjOKlCrJ [Google Scholar]

- van Cauwenberg J., De Bourdeaudhuij I., De Meester F., Van Dyck D., Salmon J., Clarys P., & Deforche B (2011). Relationship between the physical environment and physical activity in older adults: A systematic review. Health & Place, 17, 458–469. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu S., & Yu S. A. M (2001). An excess of culture: The myth of shared care in the Chinese community in Britain. Ageing and Society, 21, 681–699. doi:10.1017/S0144686X01008339 [Google Scholar]

- Forrester S. N., Gallo J. J., Whitfield K. E., & Thorpe R. J (2018). A framework of minority stress: From physiological manifestations to cognitive outcomes. The Gerontologist, 59, 1017–1023. doi:10.1093/geront/gny104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke T., Tong C., Ashe M. C., McKay H., & Sims-Gould J.; Walk the Talk Team (2013). The secrets of highly active older adults. Journal of Aging Studies, 27, 398–409. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2013.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia C., Garcia M. A., Chiu C. T., Rivera F. I., & Raji M (2018). Life expectancies with depression by age of migration and gender among older Mexican Americans. The Gerontologist, 59, 877–885. doi:10.1093/geront/gny107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner P. J. (2011). Natural neighborhood networks—Important social networks in the lives of older adults aging in place. Journal of Aging Studies, 25, 263–271. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2011.03.007 [Google Scholar]

- George U., & Ramkissoon S (1998). Race, gender, and class: Interlocking oppressions in the lives of South Asian women in Canada. Affilia, 13, 102–119. doi:10.1177/ 088610999801300106 [Google Scholar]

- Gile D. (2001). Consecutive vs. simultaneous: Which is more accurate?. Interpretation Studies, 1, 8–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hirvensalo M., Rantanen T., & Heikkinen E (2000). Mobility difficulties and physical activity as predictors of mortality and loss of independence in the community-living older population. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 48, 493–498. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04994.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho C. (2009). Migration as feminisation? Chinese women’s experiences of work and family in Australia. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 32, 497–514. doi:10.1080/13691830600555053 [Google Scholar]

- Koehn S., Habib S., & Bukhari S (2016). S4AC case study: Enhancing underserved seniors’ access to health promotion programs. Canadian Journal on Aging = La Revue Canadienne du Vieillissement, 35, 89–102. doi:10.1017/S0714980815000586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehn S., Neysmith S., Kobayashi K., & Khamisa H. (2013). Revealing the shape of knowledge using an intersectionality lens: Results of a scoping review on the health and health care of ethnocultural minority older adults. Ageing & Society, 33, 437–464. doi:10.1017/S0144686X12000013 [Google Scholar]

- Kohn M., Belza B., Petrescu-Prahova M., & Miyawaki C. E (2016). Beyond strength: Participant perspectives on the benefits of an older adult exercise program. Health Education & Behavior, 43, 305–312. doi:10.1177/1090198115599985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton M. P. (1982). Competence, environmental press, and the adaptation of older people. In Lawton M.P., Windley P. G. & Byerts T.O. (Eds.), Aging and the Environment (pp. 33–59). New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews A. E., Laditka S. B., Laditka J. N., Wilcox S., Corwin S. J., Liu R., … Logsdon R. G (2010). Older adults’ perceived physical activity enablers and barriers: A multicultural perspective. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 18, 119–140. doi:10.1123/japa.18.2.119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse J. (1995). The significance of saturation. Qualitative Health Research, 5, 147–169. doi:10.1177/104973239500500201 [Google Scholar]

- Napier A. D., Ancarno C., Butler B., Calabrese J., Chater A., Chatterjee H., … Woolf K (2014). Culture and health. Lancet (London, England), 384, 1607–1639. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61603-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng E., Lai D. W. L., Rudner A. T., & Orpana H (2012). What do we know about immigrant seniors aging in Canada? A demographic, socio-economic and health profile. Toronto, ON: CERIS- The Ontario Metropolis Centre; Retrieved from http://site.ebrary.com/lib/ubc/Doc?id=10545044&ppg=1 [Google Scholar]

- Plouffe L., & Kalache A (2010). Towards global age-friendly cities: Determining urban features that promote active aging. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 87, 733–739. doi:10.1007/s11524-010-9466-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruchno R. A., Wilson-Genderson M., & Cartwright F. P (2012). The texture of neighborhoods and disability among older adults. Journal of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67, 89–98. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbr131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosso A. L., Auchincloss A. H., & Michael Y. L (2011). The urban built environment and mobility in older adults: A comprehensive review. Journal of Aging Research, 2011, 816106. doi:10.4061/2011/816106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saelens B. E., & Handy S. L (2008). Built environment correlates of walking: A review. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 40, S550–S566. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e31817c67a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwanen T., & Ziegler F (2011). Wellbeing, independence and mobility: An introduction. Ageing & Society, 31, 719–733. doi:10.1017/S0144686X10001467 [Google Scholar]

- Shen C., Lee S. Y., Lam T. H., & Schooling C. M (2016). Is traditional Chinese exercise associated with lower mortality rates in older people? Evidence from a prospective Chinese elderly cohort study in Hong Kong. American Journal of Epidemiology, 183, 36–45. doi:10.1093/aje/kwv142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siren A., & Hakamies-Blomqvist L (2006). Does gendered driving create gendered mobility? Community-related mobility in Finnish women and men aged 65+. Transportation Research Part F, 9, 374–382. doi:10.1016/j.trf.2006.06.010 [Google Scholar]

- Son G. R., & Kim H. R (2006). Culturally familiar environment among immigrant Korean elders. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice, 20, 159–171. doi:10.1891/rtnp.20.2.159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada (2012). Immigration and ethnocultural diversity in Canada. Statistics Canada, Ottawa, ON: Retrieved from http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/99-010-x/99-010-x2011001-eng.cfm [Google Scholar]

- Thompson L. (1991). Family work: Women’s sense of fairness. Journal of Family Issues, 12, 181–196. doi:10.1177/019251391012002003 [Google Scholar]

- Tong C. E., Franke T., Larcombe K., & Sims Gould J (2017). Fostering inter-agency collaboration for the delivery of community-based services for older adults. British Journal of Social Work, 48, 390–411. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcx044 [Google Scholar]

- Tong C. E., Sims Gould J., & McKay H. A (2018). Physical activity among foreign-born older adults in Canada: A mixed-method study conducted in five languages. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 26, 396–406. doi:10.1123/japa.2017-0105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tudor-Locke C., Craig C. L., Aoyagi Y., Bell R. C., Croteau K. A., De Bourdeaudhuij I., … Blair S. N (2011). How many steps/day are enough? For older adults and special populations. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 8, 80. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-8-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umstattd Meyer M. R., Janke M. C., & Beaujean A. A (2014). Predictors of older adults’ personal and community mobility: Using a comprehensive theoretical mobility framework. The Gerontologist, 54, 398–408. doi:10.1093/geront/gnt054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walk Score (2016). Living in sunset Vancouver Retrieved August 2017, from https://www.walkscore.com/CA-BC/Vancouver/Sunset

- Walk Score (2018). Walk score methodology Retrieved October 2018, from https://www.walkscore.com/methogology

- Webber S. C., Porter M. M., & Menec V. H (2010). Mobility in older adults: A comprehensive framework. The Gerontologist, 50, 443–450. doi:10.1093/geront/gnq013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2015). Physical activity: Fact sheet 385 Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs385/en/

- Wiles J. L., Leibing A., Guberman N., Reeve J., & Allen R. E (2012). The meaning of “aging in place” to older people. The Gerontologist, 52, 357–366. doi:10.1093/geront/gnr098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen I. H., Michael Y. L., & Perdue L (2009). Neighborhood environment in studies of health of older adults: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 37, 455–463. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]