Abstract

Introduction

Salt intake in China is twice the upper limit recommended by the WHO, and nearly 80% of salt is added during cooking. This study will develop a package of salt reduction interventions targeting home cooks and evaluate its effectiveness and feasibility for scale-up.

Methods and analysis

A cluster randomised controlled trial design is adopted in this study, which will be conducted in six provinces covering northern, central and southern China. For each province, 10 communities/villages (clusters) with 13 families (one cook and one adult family member) will be selected in each cluster for evaluation. In total, 780 home cooks and 780 adult family members will be recruited. The home cooks in the intervention group will be provided with the intervention package, including community-based standardised offline and online health education and salt intake monitoring. The duration of the intervention will be 1 year. The primary outcome is the difference between the intervention and control group in change in salt intake as measured by 24 hours urinary sodium from baseline to the end of the trial. The secondary outcome is the difference between the two groups in the change in salt-related knowledge, attitude and practice and blood pressure (BP).

Ethics and dissemination

The study has been approved by The Queen Mary Research Ethics Committee (QMERC2018/13) and Institutional Review Board of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (No. 201801). The study findings will be disseminated widely through conference presentations and peer-reviewed publications and the general media.

Trial registration number

ChiCTR1800016804.

Keywords: protocols & guidelines, public health, salt reduction

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A new approach will be developed to achieve long-term, sustainable progressive lower salt intake.

A 7-day salt surveillance method will be applied to estimate the salt intake of every member of the family to motivate the target population to reduce salt intake.

The study covers a wide range of the population through the inclusion of home cooks and their family members from diverse areas, including northern, central and southern China.

The study will be carried out in China only; however, the method could potentially be adopted by many other developing countries where most of the salt in the diet is added by consumers.

Introduction

Excess dietary salt consumption is an important risk factor for high BP, stroke, cardiovascular disease and other adverse health outcomes.1–3 As a result, in 2003, the WHO and the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization issued a joint report calling for a reduction in salt intake in the population to less than 5 g per day (<2,000 mg sodium).4 It has been estimated that the mean salt consumption in 181 of 187 countries exceeded the daily intake of salt recommended by the WHO in 2010, and 51 of these countries reported mean intakes greater than double the recommended amount.5 In April 2019, the Lancet published the latest series of studies on the global burden of disease,6 which found that 3 million deaths were attributable to a high-salt diet in 2017.

Salt reduction is highly cost-effective worldwide.7 8 It has been estimated that a regulatory intervention to reduce salt intake by 3 g per day would save 194,000 to 392,000 quality-adjusted life-years and $10–$24 billion in healthcare costs every year in the USA.9 At the United Nations General Assembly in 2011, the WHO identified population salt reduction as a priority intervention for ameliorating the global burden of non-communicable diseases.10 In 2013, the WHO member states agreed on a global target of a 30% relative reduction salt intake in the population to be achieved by 2025.11 Many developed countries have introduced programmes that seek to reduce population-level salt intake, including the UK, Finland, Japan, the USA and Canada.12

In China, the current salt intake situation is not satisfactory. High salt intake is the third leading risk factor contributing to death and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs).13 A cohort of 16,869 Chinese adults aged 20–60 years over the period of 1991–2009 indicated that salt intake remains at high levels, double those of WHO recommendations.14 A study used two methods (24 hours urine collection and 24 hours dietary recall) to measure salt intake in rural China, and the results showed that mean 24 hours urinary sodium excretion was 13 g and 24 hours dietary salt intake was 10 g.15 In 2012, a report examining Chinese residents’ chronic diseases and nutrition using a dietary survey showed that the average daily salt intake for Chinese adults was 10.5 g.16

In contrast to Western countries, in China, most dietary salt comes from salt and high-salt condiments that are added during cooking. A survey involving nine provinces of China showed that, in 2006, the main sources of dietary sodium were from salt in home cooking (71.5%) followed by soy sauce (8.3%).17

The Chinese government has been making great efforts in salt intake surveillance and salt reduction interventions. The Shandong-MOH Action on Salt and Hypertension project18 and Healthy Lifestyle for All initiative19 are two representative interventions. Culturally tailored salt reduction interventions have been applied in various groups and sites, including the distribution of salt restriction spoons and the encouragement of people to use the minimum amount of salt to reduce the amount of salt added during cooking.20 However, the effect of such interventions must be evaluated in a more rigorous way.21

Since cooking salt is the largest source of salt intake in China, home cooks, who are responsible for purchasing food and preparing meals for their families, should be given special attention during intervention activities. In Japan, cooking classes for housewives effectively reduced salt intake from 9.57 g/day to 8.95 g/day after a 2-month intervention.22 In China, studies specifically focusing on salt reduction among housewives are scarce, and the type of interventions that are effective for family salt reduction remain unclear. Hence, this study will be undertaken among home cooks in six provinces of China to explore the feasibility of reducing salt intake by means of community-based intervention which, if proven successful, will be applied on a broader scale.

Our primary objective is to increase salt awareness in home cooks and to reduce the amount of salt used during cooking, thus helping the population reduce salt intake by at least 1 g/day. The specific objectives include the following: (1) to develop a package of salt reduction interventions through home cooks that are applicable to community families and (2) to evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention package by carrying out a cluster randomised trial with an intervention duration of 12 months.

Methods and analysis

Overall study design

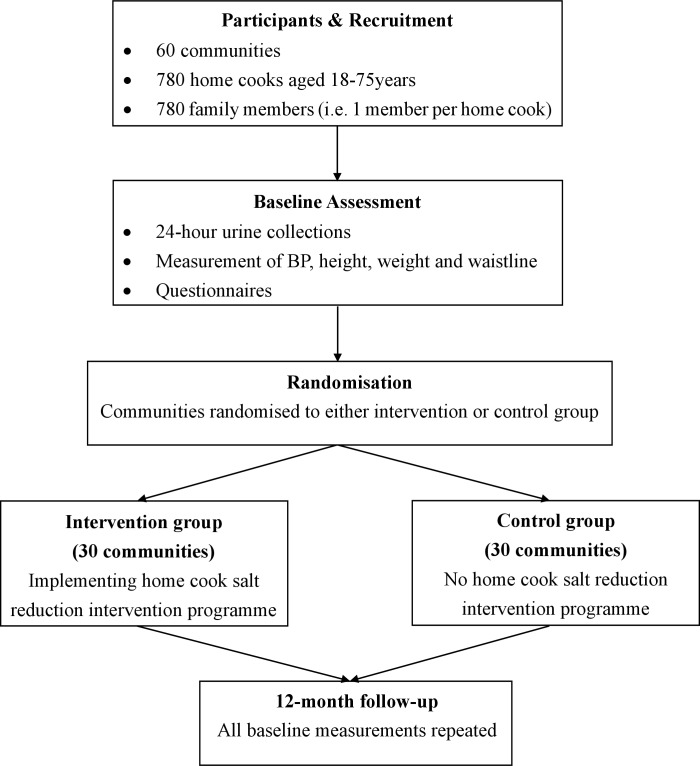

Using a cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT) design, 60 communities will be selected from six provinces. A baseline survey will be carried out before randomisation among 1,560 participants recruited from the 60 communities. The communities will be allocated randomly to the intervention or control group. Information on salt-related knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP), BP and 24-hour urinary sodium will be collected. The intervention group will receive the salt reduction intervention for 1 year (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Home cook intervention trial design. BP, blood pressure.

Study setting

Considering the geographical location, economic level and dietary habits, our study will be undertaken in selected counties from six provinces in Qinghai, Hebei, Heilongjiang, Sichuan, Jiangxi and Hunan. The interventions will be targeted to all home cooks and their family members in the selected communities.

Outcomes

The primary outcome is the difference between the intervention and control group in the change in salt intake as measured by 24-hour urinary sodium from baseline to the end of the trial.

The secondary outcome is the difference between the two groups in the change in salt-related KAP and BP.

Study population

Selection of communities

A county/district will be selected from each province, and 10 communities will be selected from each county/district. For the selection of communities, we will take into consideration the geographical area, urbanisation, size of the populations, age structure of the populations, economic status and health service resources, among others, to ensure all the communities have similar characteristics. The selected communities should have local workers to carry out the intervention activities from the primary health service supported by the neighbourhood committee (women's federation workers). Communities involved in other salt reduction projects should be excluded.

Selection of participants

Participants will be randomly selected according to age and sex. Inclusion criteria for participants include the following: (1) age of 18–75 years; (2) two family members from each family, one of whom is the major cook and the other of whom is another adult family member (better to be of different gender, spouse is preferred); (3) consumption of homemade meals at least 4 days per week by both of the family members; and (4) residence in the community for more than 6 months and no relocation plans in the next 24 months. The exclusion criteria include the following: (1) women who are pregnant or lactating; (2) individuals currently participating in any other clinical trial; and (3) individuals who cannot or refuse to collect 24 hours urine.

Randomisation

Sixty communities (clusters) will be randomly assigned (1:1) to either the intervention or the control group. Randomisation will be stratified by the geographical area (urban or rural), size of the population, economic status and health service resources. Randomisation will be carried out using a computer-generated random number system by an independent statistician who will be blinded to the identity of the communities. The randomisation will be implemented after receiving written consent and completing the baseline assessments. Therefore, the participants and the local investigators who undertake participant recruitment and data collection will be unaware of the allocation until commencement of the intervention.

Intervention

The intervention group will receive the salt reduction intervention package developed in this study, while the control group will not receive any of the interventions. The primary health staff will collaborate with workers from the neighbourhood committee and/or local women’s federation to carry out the following interventions under the guidance of the local centers for disease dontrol and prevention (CDC). The salt reduction intervention package will include the following.

A supportive environment, such as posters, brochures, videos and local broadcasts, to deliver core messages regarding salt reduction. We will develop brochures, posters, videos and audio materials about salt reduction targeting home cooks. Additionally, posters will be put up in communities and markets. Videos will be played in primary health institutions and at community activities organised by neighbourhood committees.

Lectures on salt reduction knowledge and skills. We will develop a set of standard slides to disseminate knowledge and skills to reduce salt intake for the target population. In the intervention communities, these slides will be provided for the local health institutions. They will organise and deliver lectures to the participants, especially the home cooks, once every 2 months. A total of six training lectures will be delivered in 12 months. The brief contents of the six courses will include salt-related health outcomes, sources of salt intake, low-sodium salt, misunderstandings of salt reduction, how to reduce salt intake during cooking or when eating outside the home and how to wisely choose low-salt prepackaged food.

A 7-day salt intake monitoring activity. This method will be used to estimate the amount of salt intake for every member of the family and improve the awareness of salt reduction among the target population. Participants will record the frequency of dining out, consumption of processed foods and amount of salt added during cooking. The added salt will be assessed by weighing salt, soy sauce and other primary salty condiments on the first and last day of the evaluation period.23 Additionally, the local CDCs and primary health institutions will help participants with the results estimated by this method and remind the families about their salt intake in relation to the set targets and highlight further action plans.

Online health education. The national project team will publish core knowledge on salt reduction through the WeChat public account to conduct health education for the public.

Sample size

Based on the School-EduSalt trial,24 assuming an SD of 24-hour urinary sodium excretion of 85 mmol/day and an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.05, we estimated that a sample size of 1,426 individuals (713 home cooks and 713 family members) would provide a power of 80% (with a two-sided alpha=0.05) to detect a difference in mean 24-hour urinary sodium ≥20 mmol/day (1 g/day salt) between the intervention and control group, allowing for a 20% drop-out rate of participants. We aim to recruit one home cook and one family member per household to ensure that the number of households in every community remains the same. We will select 12 households in each community, resulting in a total of 720 households and 1,440 individuals. In addition, considering that the response rate of 24 hours urine collection is often low,25 we have decided to add one more family per community, resulting in the recruitment of 1,560 individuals (780 home cooks and 780 family members) into the study for evaluation.

Data collection

All outcome measurements and assessments will be carried out at baseline and at the end of the trial in exactly the same way in all communities for all participants, irrespective of their assignment to the intervention or control group.

The participants will be carefully instructed on how to accurately collect 24-hour urine by trained research staff. On the first day, the participants will be asked to visit the survey location. The researchers will ask the participants to empty their bladders and discard the urine. The researchers will record the start time and date of the 24-hour urine collection. They will then supply the participants with collection equipment including containers and collection aids. At the same time, on the second day, the participants will be asked to bring the urine collection bottles back to the survey location and to pass the last urine into the container. The researchers will record the finish time of the 24-hour urine collection. During the 24-hour urine collection period, the participants will be asked to take spare urine containers with them to work. In case the participant misses one or more urine voids or spillage occurs, the participant will be asked to perform an additional 24-hour urine collection. For each participant, the 24-hour urine will be collected on the same days of the week for the baseline visit and follow-up visit at the end of the trial. We will measure urine volume, sodium, potassium and creatinine. An ion-selective electrode method will be used for sodium and potassium analysis and an enzymatic method for the creatinine assay. The 24-hour urinary creatinine together with the urine volume will be used to determine if the collection is likely to be complete. The biochemist who performs the measurements of urinary electrolytes will be unaware of the group to which the participant is allocated.

In addition to 24-hour urine collection, we will measure BP and heart rate using a validated automatic machine with the appropriate cuff size. Three readings will be taken for the right arm at 1–2 min intervals in a sitting position after the participant has rested for 10 min in a quiet room. Body weight, height and waist circumference will also be measured. A survey on KAP related to salt will be completed via questionnaire.

The RCT data will be collected through a specially designed mobile device-based electronic data capture system (mEDC) by well-trained field investigators. The RCT data include information on demographics, social-economic information, KAP, measurements of height, weight, waist circumference, BP, heart rate, 24-hour urine volume and electrolytes, as well as information about the intervention.

Additionally, to ensure the quality of the intervention, quality control will be established at every step of the trial using the electronic system.

Data management

All cleaned and locked datasets together with the study design, questionnaire, code list and definition of database and variables will be stored with a unique ID number attached but no personal identifiers, in the China CDC, following an established standard operating procedure for data security. To guarantee the data security, the mobile app developer must follow the ‘Mobile Application Information Service Regulation’ issued by the Cyberspace Administration of China in 2016. Although personal data are accessible to the app developer, the disclosure of such information is prohibited. In addition to the development and maintenance of a mEDC, an information technology team will also provide the data management service during the study to guarantee the safety, integrity and proper use of the data collected through the mEDC.

Statistical methods

The difference in 24-hour sodium excretion as well as the secondary outcomes between the two groups will be compared using linear mixed models with participants nested within family units and families nested within community/village units. We will include group (intervention and control), time (baseline and end of trial) and time × group interactions, with the time × group interaction term indicating different changes by group from baseline to the end of the trial. To account for missing data on continuous outcomes, we will use the likelihood-based random effects model that uses all available data and provides valid estimates of the intervention effects when data are missing at random. We will adjust for the stratification variables at randomisation and potential confounding variables. We will also carry out various sensitivity analyses to examine the robustness of the conclusions of the primary analysis.

SAS V.9.4 will be used for the analyses. The results will be reported as the mean, SD, SE and 95% CI when appropriate. All analyses will be two sided, and p<0.05 will be considered significant.

Project timelines

Recruitment of communities and participants was started in October 2018. Baseline assessments were carried out between October and December 2018. As the intervention duration is 1 year, the final follow-up assessments will be carried out between October and December 2019.

Expected outcome and potential impact

The study will provide a feasible and effective approach to achieving a sustainable reduction in salt intake by targeting home cooks. The offline intervention methods combined with the online intervention are particularly advantageous over traditional methods. Therefore, the results should be generally applicable to the whole Chinese population. If the programme is implemented and sustained across China, it will reduce population salt intake and thereby prevent hundreds of thousands of strokes, heart attacks and heart failure each year, leading to major cost-savings to individuals, their families and health services.

Although our study will be conducted in China, the home cook intervention programme to reduce salt could potentially be adopted by many other countries where most of the salt in the diet is added by consumers, which will have great public health implications.

Patient and public involvement

No patient involved.

Ethics and dissemination

Written consent will be obtained from all participants in the research according to well-established practices. Every participant has the right to withdraw from the study at any time.

There are no substantive ethical issues associated with the conduct of our research project. The collection of urine samples constitutes inconvenience but no risk to the individuals involved. A modest reduction in salt intake has no risk to the participants.

During this study, if a participant is found to have high BP, we will recommend that he or she sees a doctor, and if he or she agrees, we will help make an appointment with a doctor in a local hospital.

The findings of this study will be disseminated through conference presentations, peer-reviewed publications and the general media.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the local CDC and primary health staff who shared their opinions regarding the development of the intervention programme.

Footnotes

Twitter: @0000-0003-2725-9939

JM and PZ contributed equally.

XZ and XH contributed equally.

Contributors: XZ and XH contributed to this work equally. JM, PZ, XZ, YL, FJH and GAM conceived the project and designed the study. XZ, XH, YL and RL designed the intervention tools. All authors contributed to the development of the intervention and evaluation. XZ and XH wrote the first draft of the manuscript. JM, FJH, PZ, YL, GAM, JW and ZY revised the manuscript draft. All authors contributed to the refinement of the study protocol and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The study is being funded in full by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) using Official Development Assistance funding (16/136/77).

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests: FJH is a member of Consensus Action on Salt & Health (CASH) and World Action on Salt & Health (WASH). Both CASH and WASH are non-profit charitable organisations, and FJH has not received any financial support from CASH or WASH. GAM is Chairman of Blood Pressure UK (BPUK), Chairman of CASH, WASH and Action on Sugar. BPUK, CASH, WASH and Action on Sugar are non-profit charitable organisations. GAM has not received receive any financial support from any of these organisations.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Brown IJ, Tzoulaki I, Candeias V, et al. Salt intakes around the world: implications for public health. Int J Epidemiol 2009;38:791–813. 10.1093/ije/dyp139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mozaffarian D, Fahimi S, Singh GM, et al. Global sodium consumption and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med 2014;371:624–34. 10.1056/NEJMoa1304127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.He FJ, Li J, Macgregor GA. Effect of longer term modest salt reduction on blood pressure: cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ 2013;346:f1325. 10.1136/bmj.f1325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases: report of a joint WHO/FAO expert consultation(WHO Technical Report Series 916), 2003. Available: https://apps.who.int/nutrition/publications/obesity/WHO_TRS_916 [PubMed]

- 5.Powles J, Fahimi S, Micha R, et al. Global, regional and national sodium intakes in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis of 24 H urinary sodium excretion and dietary surveys worldwide. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003733. 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.GBD 2017 Diet Collaborators Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet 2019;393:1958–72. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30041-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asaria P, Chisholm D, Mathers C, et al. Chronic disease prevention: health effects and financial costs of strategies to reduce salt intake and control tobacco use. Lancet 2007;370:2044–53. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61698-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prabhakaran D, Anand S, Watkins D, et al. Cardiovascular, respiratory, and related disorders: key messages from disease control priorities, 3rd edition. Lancet 2018;391:1224–36. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32471-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bibbins-Domingo K, Chertow GM, Coxson PG, et al. Projected effect of dietary salt reductions on future cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 2010;362:590–9. 10.1056/NEJMoa0907355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010, 2011. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44579

- 11.World Health Organization Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013-2020, 2013. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/94384

- 12.Trieu K, Neal B, Hawkes C, et al. Salt Reduction Initiatives around the World - A Systematic Review of Progress towards the Global Target. PLoS One 2015;10:e0130247. 10.1371/journal.pone.0130247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou M, Wang H, Zeng X, et al. Mortality, morbidity, and risk factors in China and its provinces, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet 2019;394:1145–58. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30427-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du S, Neiman A, Batis C, et al. Understanding the patterns and trends of sodium intake, potassium intake, and sodium to potassium ratio and their effect on hypertension in China. Am J Clin Nutr 2014;99:334–43. 10.3945/ajcn.113.059121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson CAM, Appel LJ, Okuda N, et al. Dietary sources of sodium in China, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, women and men aged 40 to 59 years: the INTERMAP study. J Am Diet Assoc 2010;110:736–45. 10.1016/j.jada.2010.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Disease Control Bureau of National Health and Family Planning Commission of China Report on Chinese Residents’ Chronic Disease and Nutrition (2015). Beijing, China: People's Medical Publishing House, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang J-G, Zhang B, Wang Z-H, et al. [The status of dietary sodium intake of Chinese population in nine provinces (autonomous region) from 1991 to 2006]. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi 2011;45:310–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bi Z, Liang X, Xu A, et al. Hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control and sodium intake in Shandong Province, China: baseline results from Shandong-Ministry of health action on salt reduction and hypertension (SMASH), 2011. Prev Chronic Dis 2014;11:E88. 10.5888/pcd11.130423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang J, Astell-Burt T, Seo D-C, et al. Multilevel evaluation of 'China Healthy Lifestyles for All', a nationwide initiative to promote lower intakes of salt and edible oil. Prev Med 2014;67:210–5. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen J, Tian Y, Liao Y, et al. Salt-restriction-spoon improved the salt intake among residents in China. PLoS One 2013;8:e78963. 10.1371/journal.pone.0078963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang M, Moran AE, Liu J, et al. A meta-analysis of effect of dietary salt restriction on blood pressure in Chinese adults. Glob Heart 2015;10:291–9. 10.1016/j.gheart.2014.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takada T, Imamoto M, Fukuma S, et al. Effect of cooking classes for housewives on salt reduction in family members: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Public Health 2016;140:144–50. 10.1016/j.puhe.2016.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang L, Zhao F, Zhang P, et al. A pilot study to validate a standardized one-week salt estimation method evaluating salt intake and its sources for family members in China. Nutrients 2015;7:751–63. 10.3390/nu7020751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He FJ, Wu Y, Ma J. A school-based education programme to reduce salt intake in children and their families (School-EduSalt): protocol of a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2013;3. 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hawkes C, Webster J, Corinna H, Jacqui W, Murielle B. National approaches to monitoring population salt intake: a trade-off between accuracy and practicality? PLoS One 2012;7:e46727. 10.1371/journal.pone.0046727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.