Abstract

Limb amputations are carried out for a number of reasons, which include trauma, vascular disorders, infection, oncology and congenital abnormalities. These patients can develop multiple complications postoperatively with phantom limb pain being a well-recognised issue. That being said, phantom radiculopathy is far less encountered and can therefore be easily overlooked. There are limited cases described in literature and as a result pathophysiology is poorly understood. In this report, we present a patient who had developed phantom radiculopathy decades after his left above knee amputation surgery, which was performed after a road traffic accident. However, we were successfully able to treat the patient with foraminal epidural corticosteroid injection.

Keywords: drug therapy related to surgery, musculoskeletal and joint disorders, pain (neurology), orthopaedics, orthopaedic and trauma surgery

Background

Phantom limb syndrome is a well-known complication in patients following limb amputations. It was first described by Ambroise Pare in 1554,1 after having treated wounded soldiers who had developed pain extending beyond their amputated limbs. Despite advances in surgical and medical practice, it remains to be a common dilemma for surgeons, with incidence as high as 80%.

Nevertheless, there have not been many cases of phantom radiculopathy. This being either radicular pain superimposed on existing phantom limb pain or new onset phantom radicular pain on a previously asymptomatic patient.

In this report, we evaluate the case of a patient who had not previously suffered from phantom limb pain but had developed phantom radicular pain decades after his amputation surgery. Fortunately, we were able to successfully control the patient’s symptoms with epidural injection.

The earliest published case on phantom radiculopathy that we encountered was published in 1956.2 Since then, there have been a total of 16 reported cases.3 4 However, to the best of our knowledge, only one other case of new onset phantom radiculopathy was reported.3

Case presentation

A 45-year-old man presented to the Orthopaedic outpatient clinic with symptoms suggestive of sciatica. He had been suffering from back pain for the past 6 years. However, after lifting a heavy tyre 6 months earlier, he had developed a sharp pain that had radiated down his left buttock and down his left leg. Interestingly, he has undergone a left above knee amputation 30 years ago following a road traffic accident (figures 1 and 2). The patient stated that he was able to feel phantom sciatica that radiated from the left buttock along the lateral aspect of the thigh and then beyond his knee to the non-existent lateral aspect of the lower leg as well as the medial and lateral aspect of ankle.

Figure 1.

Patient amputation level—front.

Figure 2.

Patient amputation level—back.

On examination, he was comfortable at rest and he was able to weight bear. He had satisfactory power of his left hip and had a straight leg raise of 70° which elicited pain into the posterolateral aspect of his left thigh. Clinically his left thigh muscles appeared wasted. On the right side, he had 5/5 power of his hip, knees, ankle and extensor hallucis longus.

He had been taking regular pain killers and received physiotherapy, but it had not resulted in any improvement in his symptoms. He also received acupuncture treatments, which had helped to alleviate his pain enough to carry out daily activities like driving. Additionally, lying down and stretching helped with his symptoms.

Investigations

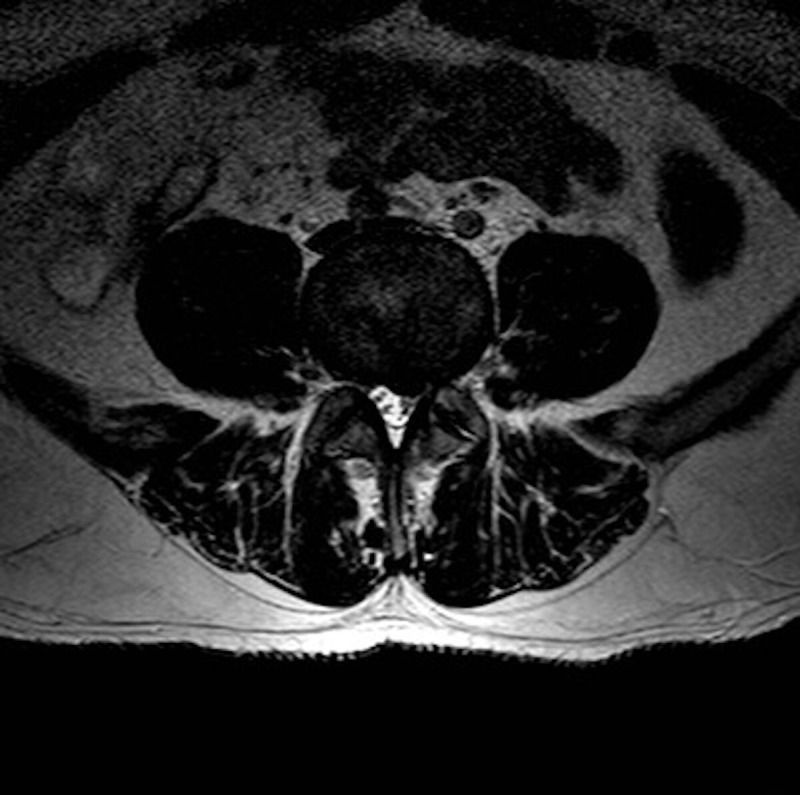

MRI of his lumbar spine was carried out and revealed an angular disc bulge at L4/L5 above the exit point of the left L5 nerve root sheath. There was also a generalised disc bulge at L5/S1 (figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

MRI axial view—illustrating the angular disc bulge at L4/L5.

Figure 4.

MRI sagittal view—disc bulges at L4/L5 and L5/S1 seen.

Treatment

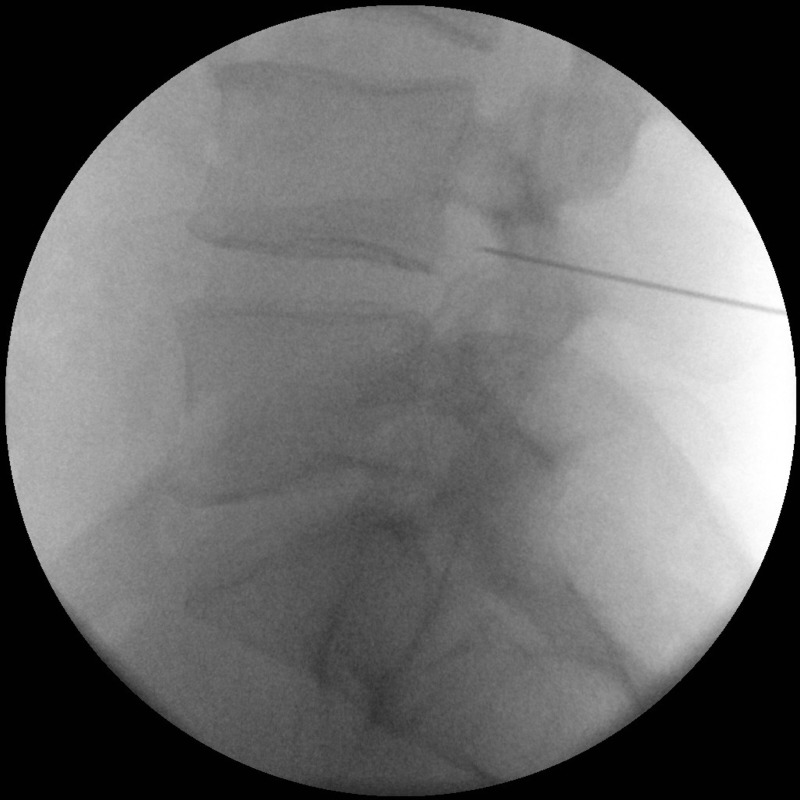

An extensive discussion took place with regards to treatment options available. The patient was presented with the options of continuing conservative management, epidural injection or surgical intervention. The risks and benefits were explained to the patient and he opted to proceed with a foraminal epidural corticosteroid injection (figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5.

Foraminal corticosteroid injection.

Figure 6.

Foraminal corticosteroid injection—lateral view.

Outcome and follow-up

Prior to treatment, the patient had described that his pain was excruciating and rated it 10/10 at its worst. However, following the foraminal epidural injection, a significant reduction in pain was noted as the patient described the pain as 2/10 at its worst. The patient was extremely satisfied with the outcome, and no further surgical intervention was required.

A telephone consultation was carried out with the patient 10 years later. The patient reported that his symptoms have been controlled very well over the past decade and only required two further epidural injections to keep his symptoms at bay. He was extremely delighted with the outcome of his treatment and informed that he has been able to continue his occupation as a mechanic.

Discussion

Sciatica or radicular pain is a common musculoskeletal disorder resulting due to nerve root compression. There are several causes; however, the most commonly encountered are intervertrabral disc herniation or intraverterbral foraminal stenosis secondary to osteophytes. The resulting symptoms are felt in the distribution of the affected nerve root and are generally described as a sharp shooting pain that radiates from the lower back to the buttock and leg of the affected side.5

Phantom limb syndrome is a well-known sequelae of limb amputation surgeries. Vast number of these patients develop phantom limb sensation where they continue to experience non-painful sensation distal to the residual limb. However, the more debilitating outcome is phantom limb pain, the characteristics of which have been described in a wide variety way: stabbing, cramping, squeezing, twisting or crushing. The pain is often nocturnal and does tend to reduce in intensity and frequency over time.6

Phantom radiculopathy is essentially a combination of the above-mentioned pathologies; however, its pathophysiology is poorly understood. Exploring this would be beyond the scope of this case report.

Clinically, the subject of this report had the hallmark symptoms of radiculopathy: lower back pain with unilateral shooting pain that radiates down the limb. The symptoms were reproduced during physical examination when performing the straight leg raise test. Finally, following treatment with intravertebral foraminal corticosteroid injections, the symptoms had markedly improved. Therefore, it is reasonable to suggest that the patient had suffered from phantom radiculopathy.

The similar case presented by Croci et al required surgical intervention to alleviate their patient’s symptoms.3 However, in this instance, we were able to successfully treat our patient with epidural injections alone.

Learning points.

Although phantom limb pain is a common phenomenon, phantom radiculopathy is far less common.

The incidence of new onset of phantom radiculopathy in patients with no previous history of phantom pain is particularly rare. Nonetheless, an Orthopaedic surgeon must be mindful of the condition when treating patients with such symptoms and should not simply conclude that it is a case of phantom limb pain.

As with treating non-amputated patients with sciatica, the treatment principles remain the same—(1) conservative with the use of exercise and physiotherapy, (2) medical, (3) corticosteroid injections and (4) surgical.

In our case, we were able to effectively treat the patient with corticosteroid epidural injections. However, if an effective level of symptom relief was not achieved, then surgical options could have been explored.

Footnotes

Contributors: MA: literature review of similar cases on the topic; drafted the case report and carried out critical revision of the article prior to the submission. SS: identified the patient and developed the concept for the report; carried out the final approval of the work to be published.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Feldman R. Current theories and treatments related to phantom limb pain. Orthotics Prosthetics 1981;35:26–30. [Google Scholar]

- 2.King AB. Phantom sciatica. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry 1956;76:72. 10.1001/archneurpsyc.1956.02330250074010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Croci D, Fandino J, Marbacher S. Phantom radiculopathy: case report and review of the literature. World Neurosurg 2016;90:699.e19–699.e23. 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orkun K, Ahmet O, Onur Y, et al. Phantom radicular pain treated with lumbar microdiscectomy: a case report. Turk Neurosurg 2017. 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.19768-16.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrew J, Herrick A, Marsh D. Musculoskeletal medicine and surgery. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engstrom B, Van de Ven C. Therapy for amputees. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2005. [Google Scholar]