Abstract

Objectives

To appraise European guidelines for acute otitis media (AOM) in children, including methodological quality, level of evidence (LoE), astrength of recommendations (SoR), and consideration of antibiotic stewardship.

Design

Systematic review of the literature.

Data sources

Three-pronged search of (1) databases: Medline, Embase, Cochrane library, Guidelines International Network and Trip Medical Database; (2) websites of European national paediatric associations and (3) contact of European experts. Data were collected between January 2017 and February 2018.

Eligibility criteria

National guidelines of European countries for the clinical management of AOM in children aged <16 years.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data were extracted using tables constructed by the research team. Guidelines were graded using AGREE II criteria. LoE and SoR were compared. Guidelines were assessed for principles of antibiotic stewardship.

Results

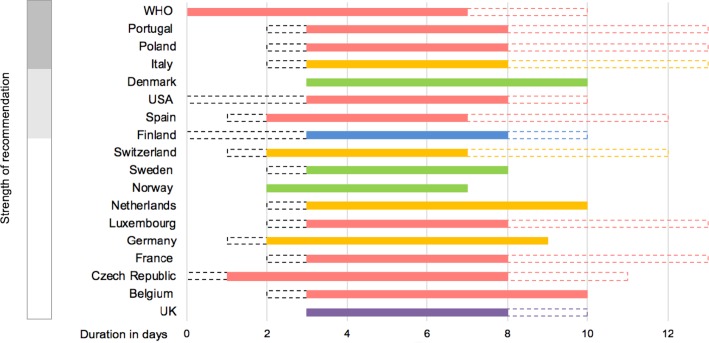

AOM guidelines were obtained from 17 or the 32 countries in the European Union or European Free Trade Area. The mean AGREE II score was ≤41% across most domains. Diagnosis of AOM was based on similar signs and symptoms. The most common indication for antibiotics was tympanic membrane perforation/otorrhoea (14/15; 93%). The majority (15/17; 88%) recommended a watchful waiting approach to antibiotics. Amoxicillin was the most common first-line antibiotic (14/17; 82%). Recommended treatment duration varied from 5 to 10 days. Seven countries advocated high-dose (75–90 mg/kg/day) and five low-dose (30–60 mg/kg/day) amoxicillin. Less than 60% of guidelines used a national or international scale system to rate level of evidence to support recommendations. Under half of the guidelines (7/17; 41%) referred to country-specific microbiological and antibiotic resistance data.

Conclusions

Guidelines for managing AOM were similar across European countries. Guideline quality was mostly weak, and it often did not refer to country-specific antibiotic resistance patterns. Coordinating efforts to produce a core guideline which can then be adapted by each country may help improve overall quality and contribute to tackling antibiotic resistance.

Keywords: acute otitis media, Europe, guidelines, children, systematic review, antibiotic stewardship

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The methodology includes the use of a comprehensive three-pronged search strategy with no language restrictions to identify guidelines from across Europe, the use of a standardised and internationally recognised guideline appraisal tool (AGREE II), the assessment of levels of evidence and strength of recommendations and the assessment of whether antibiotic stewardship, a key measure to reduce antimicrobial resistance (AMR), was considered.

The review focused only on AOM without complications; guidelines for complex otitis media requiring specialist otolaryngology input were not included. Another limitation is the consideration of whether guidelines developers used country-specific AMR patterns to assess if the recommendations of antibiotics were based on AMR data. However, there is often wide heterogeneity in terms of AMR patterns within each country.

Introduction

Acute otitis media (AOM) is one of the most common infections in childhood1 2; approximately 60% of children have had at least one episode by 4 years of age.3 It is also one of the most frequently cited reasons for antibiotic prescription in children less than 3 years of age,4 5 accounting for 14% of all antibiotic prescriptions in children in the UK.6 While both bacterial and/or viral pathogens can cause AOM,7 8 it is usually considered to be a bacterial complication of upper respiratory tract viral infection.9

The rationale for antibiotic prescription includes symptom control10 and the prevention of rare but serious complications, including mastoiditis and meningitis.11 However, studies show that up to 80% of cases resolve spontaneously without antibiotics,12 13 and antibiotics are associated with the risk of side effects including vomiting, diarrhoea and rash.13 14 In addition, the inappropriate use of antibiotics has been identified as one of the key drivers of antibiotic resistance, a global health priority.15–17 Emerging research has also demonstrated that longer antibiotic courses can lead to higher risks of resistance. Thus, providing clear guidance on appropriate antibiotic use in terms of the indications, choice and duration is considered important to help reduce antibiotic resistance.18

To promote antibiotic stewardship, the WHO recommends the development of treatment guidelines and the monitoring of local antibiotic resistance to inform the choice of antibiotics.19 National guidelines for the first-line management of AOM may play a vital role in antibiotic stewardship.20 To our knowledge, there has not been a systematic review of the quality and content of national guidelines for the management of AOM. The aim of this systematic review was to describe European guidelines for AOM in children to assess their methodological quality, to describe their evidence-based Strength of Recommendations (SoR) and to assess whether they incorporate consideration of antibiotic stewardship.

Methodology

To ensure a comprehensive review of nationally endorsed guidelines, we used a three-pronged approach that included (1) a systematic database search; (2) a website search of European national societies and (3) expert consultation.

First, a systematic search of databases was carried out using Medline, Embase, Cochrane library, Guidelines International Network and Trip Medical Database from April 2017 to February 2018. Search terms were a combination of synonyms for (1) acute otitis media and (2) guidelines. Guidelines were included if they met the following eligibility criteria: (1) they were pertaining to the management of simple AOM, excluding the management of chronic or complex otitis media cases requiring specialist otolaryngology input; (2) they were national guidelines or endorsed by the national medical society from a European Union (EU) or European Free Trade Area (EFTA) country and (3) published from the year 2000 to present. The American Association of Pediatrics (AAP)21 and the WHO22 guidelines were also included for comparison as they are widely recognised and used internationally. The search included all European languages. An initial review of titles and abstracts was performed by one reviewer (HS). Additionally, the bibliographies of all guidelines were examined to identify further relevant resources (HS). Second, the websites of national paediatric associations listed by the European Paediatric Association/Union of National European Paediatric Societies and Associations were hand-searched (HS). Finally, a network of paediatric partners across Europe were contacted (RN, SY, JED and HS) to verify if the identified guidelines were the most up to date and widely used, and in cases where we had not managed to locate any guidelines, to assist in obtaining them. The choice of search terms and final selection of full-text guidelines was performed by two reviewers (HS and JED) (see online supplementary files 1 and 2). If multiple national guidelines were found, the guideline judged to be most up to date, comprehensive and more commonly used in clinical practice was included after discussion between paediatrics partners and reviewers (HS and JED). Data were extracted using tables constructed by the research team.

bmjopen-2019-035343supp001.pdf (29.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-035343supp002.pdf (47.6KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

This systematic review was performed without patient involvement.

Guideline quality assessment

The AGREE II instrument was used independently by two reviewers (HS and JED) to determine the quality of each national guideline.23 This is a standardised instrument that appraises the methodological framework of guideline development. The six domains assessed are (1) scope and purpose, (2) stakeholder involvement, (3) rigour of development including evidence base, (4) clarity of presentation, (5) applicability and (6) editorial independence. Domains were scored on a 1–7 scale; any score that varied by >3 out of 7 was discussed and revised if this was felt to be reasonable.

Level of evidence and SoR

National scales for grading levels of evidence (LoE) and SoR were converted to Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine (OCEBM) LoE and SoR (see online supplementary files 3 and 4). However, heterogeneity between grading systems meant that a meaningful comparison was difficult. Therefore in order to compare LoE between guidelines, we reviewed (1) whether guidelines used a national/international scale of evidence, (2) whether principles of risk versus harm were assessed, (3) whether strengths and limitations of evidence were assessed and (4) whether evidence was linked to a SoR. To allow for more meaningful comparison between guidelines, we used our scores for AGREE II items 11, 9 and 12 for the above (2), (3) and (4), respectively. We converted SoR into three categories: highest, moderate and lowest grade, indicated by shading of results in tables (tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Strength of Recommendations supporting immediate or watchful waiting approach to antibiotic administration in European, AAP and WHO guidelines

| Treatment approach | Strength of recommendation |

| Immediate antibiotics for any AOM | |

| WHO | Strong recommendation |

| Immediate antibiotics for any AOM can be considered | |

| Finland | A |

| USA | Recommendation |

| Czech Republic | No grade |

| Watchful waiting approach (except for indications outlined in table 2) | |

| France | A |

| Italy | A |

| Spain | A |

| Denmark | √ |

| Poland | B |

| Portugal | IIa |

| UK | B |

| Belgium | No grade |

| Germany | No grade |

| Ireland | No grade |

| Luxembourg | No grade |

| The Netherlands | No grade |

| Norway | No grade |

| Sweden | No grade |

| Switzerland | No grade |

| Legend | |

| Highest grade | |

| Moderate grade | |

| No grade | |

Note: There is no ‘Lowest grade’ in this table.

AAP, American Association of Pediatrics; AOM, acute otitis media; WHO, World Health Organisation.

Table 2.

Indications for consideration of immediate antibiotic treatment in European and AAP guidelines

| Guideline | Age (months)* | Parental input† | Unilateral AOM‡ | Bilateral AOM aged <24 months§ | Severe symptoms¶ | Co-morbidities | Recurrent AOM | TM perforation/otorrhoea |

| Italy | – | – | + | + | + | – | – | + |

| Spain | <24 | – | – | + | + | – | + | + |

| Denmark | <6 | – | – | + | + | – | – | + |

| France | <24 | + | – | – | + | – | – | – |

| Portugal | <6 | – | – | + | + | – | + | + |

| USA | – | + | + | + | + | – | – | – |

| Norway | <12 | – | – | + | – | – | – | + |

| Poland | <6 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Belgium | <6 | – | – | + | + | + | – | + |

| Czech Republic | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | + |

| Finland | <24 | – | – | + | – | – | – | + |

| Germany | <24 | – | – | + | + | + | + | + |

| Ireland | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + |

| Luxembourg | <24 | – | – | – | + | – | – | – |

| The Netherlands | <6 | – | – | + | + | + | – | + |

| Sweden | <12 | – | – | + | + | + | – | + |

| Switzerland | <24 | – | – | + | + | + | + | + |

| UK | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Legend | ||||||||

| Highest grade | ||||||||

| Moderate grade | ||||||||

| No grade | ||||||||

‘–’ indicates that those indications are not mentioned in the guideline.

Note: There is no ‘Lowest grade’ in this table.

*Sweden: also children aged >12 years. Switzerland: <24 months of age, only if the child appears unwell.

†France: give antibiotics if parents are considered unreliable. USA: joint decision-making with parents at any age. Poland: joint decision-making with parents if child is <24 months of age.

‡Unilateral: Italy: if age <6 months. Poland: if age <24 months, then can give after joint decision-making with parents.

§Belgium, Finland and Sweden: bilateral at any age. Luxembourg: after consultation with parents.

¶Symptoms include fever, otalgia, pain, vomiting and diarrhoea. Switzerland: only if <24 months old.

AAP, American Association of Pediatrics; AOM, acute otitis media; TM, tympanic membrane.

bmjopen-2019-035343supp003.pdf (32KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-035343supp004.pdf (29.6KB, pdf)

Antibiotic stewardship

As we were unable to find a standard scoring system to assess if a clinical guideline includes consideration of antibiotic stewardship, we based our methodology on a study by Elias et al.24 We thus proposed six principles that demonstrate consideration of antibiotic stewardship based on the authors' consensus opinion. The principles are the inclusion in the guideline of (1) diagnostic criteria; (2) criteria for initiation of antibiotic therapy; (3) dosage; (4) route of administration; (5) what percentage of antibiotic recommendations was based on country-specific resistance patterns (ie, if two of three recommended antibiotics were supported by country-specific antibiotic resistance data, 67% was awarded) and (6) whether guidelines recommending amoxicillin or amoxicillin-clavulanic acid based the dosage recommendation on country-specific resistance data. These two antibiotics were chosen because in contrast to other antibiotics, a higher dosage is recommended to overcome resistant strains.25

Results

Overview of existing guidelines

The search retrieved 7340 records (figure 1). Of these, 19 guidelines were obtained. National guidelines were obtained from 17 of 32 European countries26–42 (53%) (figure 2) and 2 non-European countries/organisations (USA and WHO). The majority of these were from Western Europe and Scandinavia. The intended audience of the obtained guidelines was mainly general practitioners and paediatricians, although some included nurses and/or physician’s assistants. Of note, 4 of 17 European guidelines clearly stated that they based their findings on other national guidelines, including those of the American Academy of Paediatrics, French Agence Française de Sécurité Sanitaire des Produits de Santé (now known as Agence Nationale de Sécurité du Médicament et des Produits de Santé) and UK Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN).

Figure 1.

PRISMA systematic review flow diagram

Figure 2.

European AOM guidelines (lead group and year published).

Diagnostic criteria

Of note, 15 of 17 (88%) European guidelines outlined the signs and symptoms for diagnosing AOM (see online supplementary file 5) with considerable similarities between the guidelines. Twelve of 17 (71%) used strict combinations of three diagnostic criteria: (1) acute onset of symptoms (ie, otalgia, fever), (2) evidence of middle ear (ME) effusion (ie, tympanic membrane (TM) bulging of TM or otorrhoea on examination) and (3) inflammation of TM on examination.

bmjopen-2019-035343supp005.pdf (68.1KB, pdf)

Otoscopy

Examination tools including standard otoscopy were advised by 15 of 17 (88%) European guidelines (see online supplementary file 6). Pneumatic otoscopy (9/15; 60%) and tympanometry (7/15; 50%) were also recommended.

bmjopen-2019-035343supp006.pdf (27.5KB, pdf)

Additional investigations

No guidelines advised routine laboratory or radiographic investigations (see online supplementary file 7). Of note, 9 of 17 (53%) guidelines stated specific indications for carrying out investigations. Eight of 9 (89%) advised consideration of a culture sample of the ME via tympanocentesis, most commonly for treatment failure (6/9; 67%) and complications such as mastoiditis (4/9; 44%). Three guidelines (3/9; 33%) discussed imaging modalities such as a CT brain when investigating secondary mastoiditis.

bmjopen-2019-035343supp007.pdf (35.8KB, pdf)

Approach to antibiotic administration

There were two approaches towards antibiotic administration: a watchful waiting approach and immediate antibiotic prescription (table 1). Fifteen of 17 (88%) of the European guidelines recommended a watchful waiting approach where clinicians were encouraged to prescribe antibiotics if symptoms persisted for 1–3 days or in case of any clinical deterioration. TM perforation/otorrhoea (14/15; 93%) and severity of symptoms (13/15; 87%) were the most common indications for immediate antibiotic administration (table 2). WHO guidelines recommended all children with confirmed AOM be given antibiotics.

First-line antibiotic therapy

Of note, 14 of 17 (82%) European guidelines recommended oral amoxicillin as an option for first-line treatment (figure 3), of which 7/14 (50%) recommended a high dose (75–90 mg/kg/day) and 5/14 (36%) a low dose (30–60 mg/kg/day). Stratification to high-dose or low-dose amoxicillin for children in the UK SIGN guideline is weight-dependent; the Irish guidelines did not specify a dose. All the Nordic countries (ie, Denmark, Sweden and Norway) except Finland included oral penicillin V 24–75 mg/kg/day as a first-line choice (see online supplementary file 8).

Figure 3.

Routine first-line antibiotics: initiation, choice, duration and Strength of Recommendation.

bmjopen-2019-035343supp008.pdf (74.5KB, pdf)

Treatment failure and penicillin allergy: alternative antibiotic treatments

In case of treatment failure, per oral/intravenous amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (11/15; 73%) and intravenous/intramuscular ceftriaxone (8/15; 53%) were the most commonly recommended antibiotics. In case of penicillin allergy, guidelines advised either oral clarithromycin (8/16; 50%) or oral trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (6/16; 38%) (see online supplementary file 8).

Quality assessment: AGREE II scores

All guidelines were appraised using the AGREE II Criteria (table 3). In four of seven domains (ie, 2, 3, 5 and 6), European guidelines obtained a mean score of ≤41% while only two domains (ie, 1 and 4) scored above 63% (see online supplementary file 9a, b)

Table 3.

AGREE II scores (%) of European, AAP and WHO guidelines

| Domain number | Domain name | European mean (range) |

AAP mean | WHO mean |

| 1 | Scope and purpose | 57 (10–100) | 97 | 94 |

| 2 | Stakeholder involvement | 41 (0–92) | 67 | 58 |

| 3 | Rigour of development | 34 (0–83) | 88 | 80 |

| 4 | Clarity of presentation | 78 (21–100) | 89 | 92 |

| 5 | Applicability | 23 (0–58) | 35 | 60 |

| 6 | Editorial independence | 29 (0–96) | 54 | 83 |

AAP, The American Association of Pediatrics; WHO, World Health Organisation.

bmjopen-2019-035343supp009.pdf (74.8KB, pdf)

LoE and SoR

Of note, 10 of 17 European guidelines (59%) based their certainty of evidence (ie, LoE) and SoR on a variety of methodologies (table 4). The only crossover was between Poland and Spain which used a methodology from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. AGREE II scores for quality of the LoE were variable, and approximately half of European guidelines (8/17; 47%) scored ≤4 across all items. SoR was often based on study design (ie, multiple randomised controlled trials), but for some it was based on more subjective assessments (ie, ‘well-conducted studies’).

Table 4.

Level of Evidence in AOM guidelines

| Country | Grading system for LoE * | Score: consideration of benefits and harms (AGREE II Item 11†) | Score: strengths and limitations of the evidence (AGREE II Item 9) | Score: link between recommendations and evidence (AGREE II Item 12) |

| Belgium | INAMI | 5 | 7 | 6 |

| Czech Republic | – | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Denmark | OCEBM | 7 | 7 | 6 |

| Finland | Duodecim | 1 | 6 | 6 |

| France | ANAES | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Germany | AWMF | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| Ireland | – | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Italy | PNLG | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| Luxembourg | – | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| The Netherlands | – | 7 | 7 | 5 |

| Norway | – | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Poland | Infectious Disease Society of America | 6 | 3 | 5 |

| Portugal | European Society of Cardiology | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Sweden | – | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Switzerland | – | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Spain | Infectious Disease Society of America | 5 | 2 | 7 |

| UK | SIGN | 7 | 7 | 6 |

| USA | AAP | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| WHO | GRADE | 7 | 7 | 6 |

*If no LoE scale used, it is denoted by –.

†AGREE II scores: 1=no information in the guideline; 7=exceptional reporting.

AAP, The American Association of Pediatrics; ANAES, l'Agence Nationale d'Accréditation et d'Évaluation en Santé; AOM, acute otitis media; AWMF, Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations; INAMI, Institut National d'Assurance Maladie-Invalidité; LoE, level of evidence; OCEBM, Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine; PNLG, Programma Nazionale Linee Guida; SIGN, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network.

Antibiotic stewardship

The majority of guidelines provided diagnostic criteria for AOM, specifications on when to start antibiotics, the route of administration and the duration of treatment (table 5). However, less than half referred to country-specific AMR patterns, and four (24%) included both country-specific AMR data and specified resistance levels to amoxicillin/amoxicillin–clavulanic acid to guide local choices.

Table 5.

Antibiotic stewardship and AOM guidelines

| Do guidelines provide diagnostic criteria? | Do guidelines specify when to initiate antibiotics? | Do guidelines specify route of administration? | Do guidelines specify duration of antibiotic regimens? | Do antibiotic recommendations refer to country-specific AMR patterns? | |||

| Percentage of antibiotic recommendations that refer to country-specific AMR patterns (%) | Amoxicillin dosage that refers to country-specific AMR patterns | Amoxicillin–clavulanic acid dosage that refers to country-specific AMR patterns | |||||

| Belgium | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 80 | Yes | Yes |

| Czech Republic | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0 | Unclear | Unclear |

| Denmark | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0 | Not applicable | Unclear |

| Finland | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 63 | Yes | Yes |

| France | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0 | Unclear | Unclear |

| Germany | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0 | Unclear | Unclear |

| Ireland | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear | 0 | Unclear | Not applicable |

| Italy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 67 | Yes | Yes |

| Luxembourg | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0 | Unclear | Unclear |

| The Netherlands | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 100 | Yes | Yes |

| Norway | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0 | Unclear | Not applicable |

| Poland | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 100 | Yes | Not applicable |

| Portugal | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 71 | Yes | Yes |

| Spain | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 100 | Yes | Yes |

| Sweden | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 100 | Unclear | Not applicable |

| Switzerland | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0 | Unclear | Unclear |

| UK | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0 | Unclear | Unclear |

| USA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 100 | Yes | Yes |

| WHO | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Legend | |||||||

| Promotes antibiotic stewardship | |||||||

| Partially promotes antibiotic stewardship | |||||||

| Does not promote antibiotic stewardship | |||||||

AMR, antimicrobial resistance; AOM, acute otitis media.

Discussion

Approximately half of the 32 EU/EFTA countries have AOM guidelines. Diagnosis of AOM was based on similar signs and symptoms. Tympanocentesis was commonly reserved for treatment failure. The vast majority of European guidelines advocated for a watchful waiting approach to antibiotic therapy with the most common indications for treatment being TM perforation and severity of symptoms. Amoxicillin was the most commonly recommended first-line antibiotic but with differences in terms of recommended duration and dosage. Our quality assessment found low mean AGREE II scores of ≤41% in most domains. Less than 60% of guidelines used a national or international system to rate LoE to support recommendations. Less than half of the guidelines referred to country-specific patterns of AMR.

Strengths of our study include the comprehensiveness of our three-pronged search strategy, the use of AGREE II, an internationally recognised guideline appraisal tool and an assessment of which LoE and SoR were used. Our analysis also included a qualitative assessment of whether antibiotic stewardship was considered in the development of guidelines based on five criteria. In order to provide a broad sense on whether AMR data were considered, one of the criteria was whether the antibiotic recommendations referred to national-level AMR data. However, the limitation of this is that there is often wide heterogeneity in AMR patterns within each country, therefore guidelines should ideally recommend that the antibiotic choice be adapted to available local AMR data. Another limitation is our focus on simple AOM and exclusion of guidelines about complex cases requiring otolaryngology specialist input.

Previously published works demonstrated a common consensus in criteria for AOM diagnosis, and that a watchful waiting period was the standard of care in Europe; amoxicillin was also found to be the most commonly recommended antibiotic.43–45 In comparison with these studies, our work aimed to compare additional facets of AOM management in Europe, including grading their quality, comparison of LoE and SoR and assessing their inclusion of country-specific AMR data. Zeng et al also used AGREE II scores to assess quality of upper respiratory tract infections guidelines including three AOM guidelines from Japan, USA and UK.46 We note a >10-point discrepancy in scoring in two of six domains between Zeng et al and ourselves for UK SIGN and US AAP AOM guidelines. This may indicate inter-user variability in AGREE II scoring.47 Elias et al assessed global infectious diseases guidelines and found that local AMR patterns were taken into account in 50%–75% of recommendations which is similar to our findings.

The development of clinical guidelines according to the high standards of the AGREE II criteria is a resource -intensive exercise and this may be one of the reasons why we did not identify any guidelines from some countries. Many guidelines in this study received low AGREE II scores. Many of the resource-intensive initial steps in guidelines development are universal, for example defining the objectives, the clinical questions, the target populations of patients and end users and designing a comprehensive search strategy to identify relevant evidence from the literature, a process to appraise the evidence, a way to present recommendations unambiguously and strategies to successfully implement guidelines. Replicating this process in each country to reach similar conclusions does not seem necessary nor efficient, and it may make sense for these or some of these processes to be undertaken by a core group of experts from across Europe. This is already the case for other medical specialities, for example the European Joint Task Force for cardiovascular disease prevention provides guidelines that can be used across Europe.48 The centrally developed guidelines could then be adapted in each country for recommendations, such as choice of antibiotics, which depends on local AMR patterns and immunisation coverages against the main pathogens causing AOM. This implies the implementation of robust epidemiological and standardised AMR surveillance systems in each country which is currently underway with the support of international initiatives such as the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control surveillance systems,49 and the WHO Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System.50 Other aspects that could lead to local adaptation could be local care pathways, and user and patient preferences. This approach would allow the development of guidelines of better quality and better adapted to local contexts, and it might contribute to reducing the spread of AMR.

Conclusion

Review of guidelines reveals major similarities in AOM management recommendations across Europe. Existing European guidelines scored poorly in most AGREE II domains, including items related to how evidence was gathered and appraised. Consideration of country-specific antibiotic resistance patterns appears to be limited. Centrally produced guidelines adapted for local care pathways, user and patient preferences, and for local antimicrobial resistance patterns may provide more targeted recommendations, reduce unnecessary antibiotic administration and help reduce the spread of antibiotic resistance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Professor Mike Levin and our colleagues from the PERFORM consortium, Young ESPID, and all our contacts who helped us in obtaining national guidelines: Daniela Klobassa (Austria), Jan Verbakel (Belgium), Žaneta Jelčić (Croatia), Stephanie Menikou (Cyprus), Linda Alderson (Czech Republic), Ivan Peychl (Czech Republic), Anna Turkova (Czech Republic), Rikke Jorgensen (Denmark), Juri Lindy Pedersen (Denmark), Inga Ivaskeviciene (Estonia), Piia Jogi (Estonia), Irja Lutsar (Estonia), Eda Tamm (Estonia), Esa Korpi (Finland), Niina Valtanen (Finland), Romain Basmaci (France), Jean Christophe Mercier (France), Christoph Bidlingmaier (Germany), Ulrich von Both (Germany), Florian Gothe (Germany), Johanna Krone (Germany), Konstatinos Kakleas (Greece), Valtyr Thor (Iceland), Maeve Kelleher (Ireland), Silvia Bressan (Italy), Dace Zavadska (Latvia), Simona Sabulyte (Lithuania), Armand Biver (Luxembourg), Simon Attard-Montalto (Malta), David Pace (Malta), Ingebjørg Fagerli (Norway), Arne Martin Slåtsve (Norway), Magdalena Marczyńska (Poland), Maria Pokorska-Śpiewak (Poland), Kacper Toczylowski (Poland), Carolina Costa (Portugal), Irina Branescu (Romania), Diana Moldovan (Romania), Laszlo Kovacs (Slovakia), Keti Vincek (Slovenia), Pablo Obando Pacheco (Spain), Irina Rivero (Spain), Frederico Maritinon Torres (Spain), Giannos Orfanos (Sweden), Philipp Agyeman (Switzerland), Hermione Lyall (UK), and Elizabeth Whittaker (UK).

Footnotes

Contributors: SY conceived the study. HS, JED, RN and SY all contributed to the study design. HS was responsible for the systematic database search. JED, RN and SY all contacted experts in their scientific networks to obtain additional guidelines and check the use and validity of those identified. HS and JED were responsible for data extraction including LoE, SoR and antibiotic stewardship and AGREE II scoring. HS, JED, RN and SY all contributed to the interpretation of the results, the drafting and revision of the manuscript and they agree with the final version.

Funding: RN was supported by NIHR Academic clinical fellowship and lectureship award programme. JED and SY are supported by PERFORM, a consortium funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 programme, under grant agreement No. 668303.

Disclaimer: The funding sources did not take part in the design, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report or decision to submit the article for publication. All authors had full access to all the data, and they can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Map disclaimer: The depiction of boundaries on the map(s) in this article do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. The map(s) are provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request. The primary data for this study was treatment guidelines, and these can be shared on request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Schilder AGM, Chonmaitree T, Cripps AW, et al. Otitis media. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016;2:16063 10.1038/nrdp.2016.63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palma S, Rosafio C, Del Giovane C, et al. The impact of the Italian guidelines on antibiotic prescription practices for acute otitis media in a paediatric emergency setting. Ital J Pediatr 2015;41:37 10.1186/s13052-015-0144-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaur R, Morris M, Pichichero ME. Epidemiology of acute otitis media in the postpneumococcal conjugate vaccine era. Pediatrics 2017;140:e20170181 10.1542/peds.2017-0181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coker TR, Chan LS, Newberry SJ, et al. Diagnosis, microbial epidemiology, and antibiotic treatment of acute otitis media in children: a systematic review. JAMA 2010;304:2161–9. 10.1001/jama.2010.1651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leibovitz E. Acute otitis media in pediatric medicine: current issues in epidemiology, diagnosis, and management. Paediatr Drugs 2003;5:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson PL, Gilbert RE, Long PF, et al. Has UK guidance affected general practitioner antibiotic prescribing for otitis media in children? J Public Health 2008;30:479–86. 10.1093/pubmed/fdn072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Y-J, Hsieh Y-C, Huang Y-C, et al. Clinical manifestations and microbiology of acute otitis media with spontaneous otorrhea in children. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2013;46:382–8. 10.1016/j.jmii.2013.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Dongen TMA, Venekamp RP, Wensing AMJ, et al. Acute otorrhea in children with tympanostomy tubes: prevalence of bacteria and viruses in the post-pneumococcal conjugate vaccine era. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2015;34:355–60. 10.1097/INF.0000000000000595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nokso-Koivisto J, Marom T, Chonmaitree T. Importance of viruses in acute otitis media. Curr Opin Pediatr 2015;27:110–5. 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rovers MM, Glasziou P, Appelman CL, et al. Antibiotics for acute otitis media: a meta-analysis with individual patient data. Lancet 2006;368:1429–35. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69606-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Groth A, Enoksson F, Hermansson A, et al. Acute mastoiditis in children in Sweden 1993–2007—no increase after new guidelines. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2011;75:1496–501. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2011.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenfeld RM, Vertrees JE, Carr J, et al. Clinical efficacy of antimicrobial drugs for acute otitis media: metaanalysis of 5400 children from thirty-three randomized trials. J Pediatr 1994;124:355–67. 10.1016/S0022-3476(94)70356-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Venekamp RP, Sanders SL, Glasziou PP, et al. Antibiotics for acute otitis media in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;6:CD000219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakulchit T, Goldman RD. Antibiotic therapy for children with acute otitis media. Can Fam Physician 2017;63:685–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centres for Disease Control and Prevention Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2019. Atlanta, GA. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, 2019. Available: www.cdc.gov/DrugResistance/Biggest-Threats.html [Accessed 3 Feb 2017].

- 16.Costelloe C, Metcalfe C, Lovering A, et al. Effect of antibiotic prescribing in primary care on antimicrobial resistance in individual patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2010;340:c2096 10.1136/bmj.c2096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sibbald AD. Acute otitis media in infants: the disease and the illness. Clinical distinctions for the new treatment paradigm. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2012;147:606–10. 10.1177/0194599812455780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pouwels KB, Hopkins S, Llewelyn MJ, et al. Duration of antibiotic treatment for common infections in English primary care: cross sectional analysis and comparison with guidelines. BMJ 2019;73:l440 10.1136/bmj.l440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organisation Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance, 2015. Geneva, Switzerland. Available: https://www.who.int/antimicrobial-resistance/publications/global-action-plan/en/ [Accessed 7 Jun 2018].

- 20.Laxminarayan R, Duse A, Wattal C, et al. Antibiotic resistance—the need for global solutions. Lancet Infect Dis 2013;13:1057–98. 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70318-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lieberthal AS, Carroll AE, Chonmaitree T, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics 2013;131:e964–99. 10.1542/peds.2012-3488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organisation Recommendations for management of common childhood conditions. Evidence for technical update of pocket book recommendations. Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. Available: https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/management_childhood_conditions/en/ [Accessed 20 Jan 2017]. [PubMed]

- 23.Brouwers M, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. For the agree next steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in healthcare. CMAJ 2010;182:E839–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elias C, Moja L, Mertz D, et al. Guideline recommendations and antimicrobial resistance: the need for a change. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016264 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Opatowski L, Mandel J, Varon E, et al. Antibiotic dose impact on resistance selection in the community: a mathematical model of beta-lactams and Streptococcus pneumoniae dynamics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010;54:2330–7. 10.1128/AAC.00331-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Institut National D'Assurance Maladie-invalidité L'usage rationnel des antibiotiques chez l'enfant en ambulatoire, 2016. [The rational usage of antibiotics in ambulating children]. Available: https://www.inami.fgov.be/SiteCollectionDocuments/consensus_texte_court_20160602.pdf [Accessed 5 Jan 2018].

- 27.Bébrová EJB, Cizek H, Vaclav D, et al. Doporučený postup pro antibiotickou léčbu komunitních respiračních infekcí v primární péči.[The recommended procedure for antibiotic treatment of community respiratory infections]. Vox pediatrae 2011;11. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dansk Selskab for Almen Medicin Luftvejsinfektioner.− diagnose og behandling 2014. [Respiratory tract infections—diagnosis and treatment 2014). Available: http://vejledninger.dsam.dk/luftvejsinfektioner/ [Accessed 10 Jan 2017].

- 29.Suomalainen Lääkäriseura Duodecim Välikorvatulehdus (lasten äkillinen). [Otitis media sudden onset of children], 2017. Available: https://www.kaypahoito.fi/hoi31050 [Accessed 12 Dec 2017].

- 30.Agence française de sécurité sanitaire des produits de santé Recommandations de Bonne Pratique- Antibiothérapie par voie générale en pratique courante dans les infections respiratoires hautes [Recommendations for good practice- Antimicrobials by general route in current practice in upper respiratory tract infections], 2011. Available: http://www.infectiologie.com/UserFiles/File/medias/Recos/2011-infections-respir-hautes-recommandations.pdf [Accessed 10 Apr 2017].

- 31.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allegemeinmedizin und Familienmedizin (DEGAM) DEGAM-Leitlinie Nr 7-Ohrenschmerzen [DEGAM guideline Number 7—Earache], 2014. Available: https://www.awmf.org/en/clinical-practice-guidelines/search-for-guidelines.html#result-list [Accessed 4 Apr 2017].

- 32.Health Services Executive and Royal College of Physicians Ireland Acute otitis media, 2012. Available: https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/publications/clinical-strategy-and-programmes/paediatrics-acute-otitis-media.pdf [Accessed 12 Apr 2017].

- 33.Marchisio P, Bellussi L, Di Mauro G, et al. Acute otitis media: from diagnosis to prevention. Summary of the Italian guideline. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2010;74:1209–16. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2010.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Conseil Scientifique Domaine de la Santé Otite moyenne aiguë. [Acute Otitis media]. Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Damoiseaux R, Venekamp RP, Eekhof JAH, et al. NHG Standard Otitis media acuta bij kinderen [NHG Standard Otitis media acute in children]. Huisarts Wet 2014;57:648. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Antibiotikasenteret for primærmedisin Akutt otitis media [Acute otitis media], 2016. Available: http://www.antibiotikaiallmennpraksis.no/index.php?action=showtopic&topic=VMpmsqDE\ [Accessed 5 Jan 2017].

- 37.Hryniewicz W, Piotr Albrecht P, Radzikowski A, et al. Rekomendacje postępowania w pozaszpitalnych zakażeniach układu oddechowego. [Recommendations for management of in-hospital respiratory infections], 2016. Available: http://antybiotyki.edu.pl/ [Accessed 10 Jul 2017].

- 38.Departamento da Qualidade na Saúde Diagnóstico e tratamento da Otite Média Aguda na Idade Pediátrica. [Diagnosis and treatment of acute otitis media in paediatrics], 2014. Available: https://www.dgs.pt/directrizes-da-dgs/normas-e-circulares-normativas/norma-n-0072012-de-16122012-png.aspx [Accessed 15 Apr 2017].

- 39.Del Castillo Martín F, Bacquero Artigao F, de la Calle Cabrera T, et al. Asociación Española de Pediatría- Documento de consenso sobre etiología, diagnóstico y tratamiento de la otitis media aguda. [Consensus document on aetiology, diagnosis, and treatment of acute otitis media]. An Pediatr 2012;77:8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Läkemedelsverket Diagnostik, behandling och uppföljning av akut mediaotit (AOM) – ny rekommendation. [Diagnosis, treatment and follow up of acute otitis media—new recommendations]. Information från Läkemedelsverket 2010;21:10–23. Available: https://lakemedelsverket.se/otit [Accessed 5 Jan 2018].

- 41.Pediatric Infectious Disease Group of Switzerland Recommendations pour le diagnostic et le traitement de Otite moyenne aiguë, Sinusite aiguë, Pneumonie (community-acquired), et Pharyngo-amygdalite chez l’enfant. [Recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of acute otitis media, acute sinusitis, pneumonia (community acquired), and pharyngitis in children], 2010. Available: http://www.pigs.ch/pigs/frames/documentsframe.html [Accessed 2 May 2017].

- 42.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network Diagnosis and management of childhood otitis media in primary care: a national clinical guideline. Edinburgh, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ovnat Tamir S, Shemesh S, Oron Y, et al. Acute otitis media guidelines in selected developed and developing countries: uniformity and diversity. Arch Dis Child 2017;102:450–7. 10.1136/archdischild-2016-310729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Andre MAI, Hemlin C, Nasta F. Behandling av akut otitis media i andra länder - översikt över 28 nationella riktlinjer [Treatment of acute otitis media in other countries—a survey of 28 national guidelines]. Information från Läkemedelsverket 2010;21:37–43. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Toll EC, Nunez DA. Diagnosis and treatment of acute otitis media: review. J Laryngol Otol 2012;126:976–83. 10.1017/S0022215112001326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zeng L, Zhang L, Hu Z, et al. Systematic review of evidence-based guidelines on medication therapy for upper respiratory tract infection in children with agree instrument. PLoS One 2014;9:e87711 10.1371/journal.pone.0087711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marciano NJ, Merlin TL, Bessen T, et al. To what extent are current guidelines for cutaneous melanoma follow up based on scientific evidence? Int J Clin Pract 2014;68:761–70. 10.1111/ijcp.12393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, et al. 2016 European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts) developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J 2016;37:2315–81. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control TESSy—the European surveillance system: antimicrobial resistance (AMR) reporting protocol 2018. Stockholm, Sweden. Available: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/EARS-Net%20reporting%20protocol%202018.%20docx.pdf [Accessed 10 Dec 2019].

- 50.World Health Organisation Global antimicrobial resistance surveillance system (GLASS) report: early implementation 2017–2018. Geneva, Switzerland. Available: https://www.who.int/glass/resources/publications/early-implementation-report-2017-2018/en/ [Accessed 10 Dec 2019].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-035343supp001.pdf (29.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-035343supp002.pdf (47.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-035343supp003.pdf (32KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-035343supp004.pdf (29.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-035343supp005.pdf (68.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-035343supp006.pdf (27.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-035343supp007.pdf (35.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-035343supp008.pdf (74.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-035343supp009.pdf (74.8KB, pdf)