Abstract

Introduction

Digital social networks have become a key player in the ecosystem of young patients with cancer, with regard to their unique perspectives and unmet needs. This study aims to investigate the web-based social community tools and to characterise the user profile, unmet needs and goals of young patients with cancer.

Methods

A web-based survey was distributed via large-scale social network designated for young patients with cancer (age 18–45 years) Stop Cancer. The survey collected demographic data and oncological status. Primary outcome was potential goals of accessing the network; secondary outcomes were emotional impact, effect of disease status, education, marital status and employment, on user satisfaction rate.

Results

The survey was available for 5 days (10/2018) and was filled by 523 participants. Breast cancer, haematological malignancies and colorectal cancer were the most common diagnoses. The majority had non-metastatic disease at diagnosis, 79% had no evidence of disease at time of the survey. Forty-five per cent considered the network as a reliable source for medical information. Academic education was associated with higher satisfaction from the platform. There were no differences between cancer survivors and patients with active disease in patterns of platform usage. The social network had an allocated section for ‘patient mentoring’ of newly diagnosed members by survivors.

Discussion

Our study portrayed the user prototype of a social digital network among young adult patients with cancer, indicating challenging trends. Whereas social media may prove a powerful tool for patients and physicians alike, it may also serve as a research tool to appraise wide practices within a heterogeneous population. Nevertheless, it acts as a double-edged sword in the setting of uncontrolled medical information. It is our role as healthcare providers to join this race and play an active role in shaping its medical perspectives.

Keywords: young cancer, social media, communication, stopcancer

Key questions.

What is already known about this subject?

Use of social media is ubiquitous and becoming an integral part of how people communicate and learn. These diverse platforms have inevitably joined the forefront of young cancer patients’ ecosystem for coping with cancer in daily life, whether to find health information or as a safe place for support and solace. Multiple studies have surveyed online populations to identify how patients use these platforms, others have used them to identify cohorts for rare diseases. In general, these studies identify specific subgroups of patients. Studies on social media are burgeoning in other fields as well, such as in psychiatry where they have shown to reduce patient anxiety, and infectious diseases, as a means to survey health and detect disease outbreaks.

What does this study add?

Herein, we present data from a major digital social network, which is accessible to the breadth of young patients with cancer, regardless of cancer type and stage. We collected information on demographics and usage traits in order to characterise user profile of these platforms. We found no differences in platform usage between patients with active and non-active disease, suggesting a challenge in transition to survivorship. This issue can be addressed by developing designated activities geared towards aiding survivors reintegrate into the workforce, or with targeted online support groups. Social networks represent a mean for learning our young patients’ environment, patient education via interference through the platform and also a research tool.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Physicians should be aware of the rapidly changing landscape of a patient’s experience and find the appropriate way to join the discussion beyond office walls. It has the potential to improve communication with patients and the support system around them, to ensure that adequate and accurate information is delivered online, to collect data quickly and efficiently, and ultimately, to enhance patient care.

Introduction

The role of digital social networks among young patients with cancer has evolved in the biosphere of their unique perspectives and unmet needs. As digital natives, they exploit cancer-related social networks ever more frequently, leading to an emerging reality parallel to traditional medical care.1 A burgeoning variety of online resources exists today: forums, blogs, tweet chats, message boards and organisational websites2 Additionally, cellphone apps like Belong help patients stay connected. Young population turn to social media for health information and answers to age-specific issues in reintegrating in normal life. They also use it to find support and reduce anxiety.3 They place social media as a top helpful resource along with support from family and friends in a recent comprehensive Delphi panel; moreover, they most often use these resources to reduce feelings of loneliness, create a sense of belonging and as a platform for meeting others like them.2 It had been previously reported that the major digital social platforms, representing the web-based social ‘community’ tools,4 had become a potential game changer in cancer care with the potential for wide scale effects. In our previous publication in The Lancet Oncology, we described the use of social media in oncology.4 We used the online portal, Stop Cancer and studied a wide variety of young cancer patients. In only 1 week, we had gathered over 500 patients between the ages 20–45. In this following article, we show the user profile, unmet needs and goals of young cancer patients as a means to study the clinical and emotional landscape that exists in parallel to the traditional healthcare and support setting.

Methods

A web-based survey was distributed via the large-scale social network designated for young patients ith cancer (aged 18–45 years) Stop Cancer to all users. The survey collected demographic data from the variety of cancer patients such as age, sex, living arrangement, academic education, employment, religion and oncological status, such as metastatic or non-metastatic cancer, and the treatment they received. Primary outcome was potential goals of accessing the network; secondary outcomes were emotional impact, and effect of disease status, education, marital status and employment on satisfaction from using the platform. Patients were asked to rate the adequacy of statements: ‘using the platform alleviated my sense of seclusion’ and ‘using the platform induced anxiety’. All outcomes reported herein were considered statistically significant using the Fisher's exact test (p<0.05).

Results

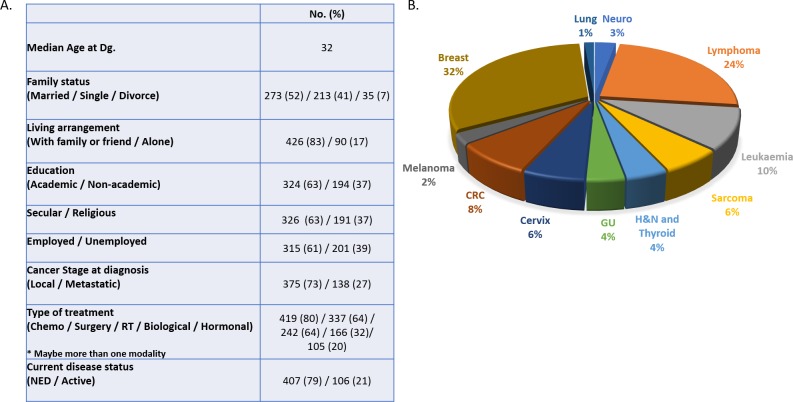

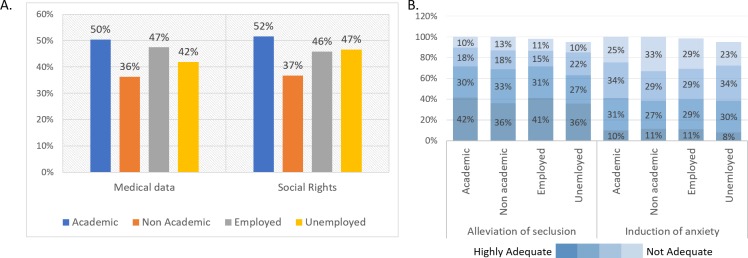

The survey was available for 5 days (2/2018) and was completed by 523 participants. As depicted in figure 1, the majority (73%) of participants had non-metastatic disease at diagnosis, and 79% had no evidence of disease at time of the survey. The most common cancer type among subjects was breast, followed by lymphoma and colorectal cancer. Among participating patients diagnoses include melanoma, sarcoma, cervix, lung, genitourinary, head and neck, thyroid, brain cancer and leukaemia. Most participants were living with a spouse or family member, 62% considered themselves secular, and the 63% had high academic education. Forty-five per cent considered the network a reliable source of medical information. As shown in figure 2A, there was no significant difference in patterns of requested information according to degree of education and employment. However, patients with higher academic degree were generally more satisfied with the online platform, as evident from figure 2B. In contrast, unemployed participants sought for less medical information and experienced better relief of seclusion sense than employed participants. There were no differences between cancer survivors and patients with active disease in patterns of platform usage, nor in domains of interest when analysing data on type of treatment received. The social network had an allocated section for ‘patient mentoring’ of newly diagnosed members by survivors, which is an interesting addition to an online platform.

Figure 1.

Demographic characteristics of stop cancer digital network users. GU, Genitourinary; RT, Radiotherapy; NED, No Evidence of Disease.

Figure 2.

Stop cancer users by education and employment (A) Seeking information by education (academic—college/university; non-academic—high school) and employment status (B) Psychosocial impact—alleviation of seclusion versus induction of anxiety.

Discussion

The ubiquitous use of modern technology and social media networking has brought this domain into the forefront of young patients’ ecosystem for coping with cancer in daily life. A burgeoning variety of online resources exists today created for and by patients targeting a range of prespecified populations, including forums, blogs, tweet chats, message boards and organisational websites. These convenient online platforms offer another form of support in addition to traditional patient support and self-help groups and long-standing hospital-based methods of communication. Often healthcare providers are unaware of the significance of such networks—as a parallel existence well beyond the traditional patient–doctor office encounter. Crucially, these platforms are patient driven and can provide key insights into methods to improve patient experience. Herein, we delineate patient and disease characteristics as well as correlations between users and usage, which can be used to target specific populations.

Nevertheless, essential processes such as transition to survivorship and discussion on disease course intermingle and lead to mixed conceptions that cannot be differentiated between cured and active patients. This is evident in our study, as there were no significant differences between subjects with active disease and those with no evidence of disease, in terms of their use of the platform. Additionally, the majority of them were free of disease at time of completion of the survey, yet were still actively using the platform. Perhaps more emphasis may be placed within the network in aiding survivors in their psychological and physical reentry into society and the workforce.

Social media may prove a powerful tool for patients and physicians alike, to foster an environment of care-continuity and patient-centred medicine, to strengthen the patient–doctor relationship and connect clinicians with the broad community beyond office walls. Importantly, social media is also a robust research tool in massive scales.5 6 This unique and expanding phenomenon may act as a double-edged sword—a fertile core of easily accessible knowledge but also as an uncontrolled medical information source. It is our role as healthcare providers to join this race and play an active role in shaping its medical perspectives.

Our results indicated that the majority of patients using the portal had non-metastatic disease, casting doubt on the relevance to those with more advanced cancer and issues of end of life. Perhaps a portal geared towards metastatic patients could better target their needs and identify alternative patterns of usage of online social media networks.

While easy and convenient, computer-based communication cannot replace the traditional classic doctor and patient encounter and relationship that we know so well. Furthermore, negative, inaccurate health information can be distributed online.7 A problem to which we have limited solutions. Additionally, privacy issues arise when confronted with social media.8

In conclusion, use of social media is an important game-changer in the practice of oncology. It is crucial that we, as oncologists, join the race and shape its medical perspectives.

Footnotes

Contributors: IB-A: conception, writing the manuscript. TG-L: literature search, data collection, data analysis. IT: literature search, writing the manuscript. EF: conception and data interpretation. ES: conception and data interpretation. FL: conception, data analysis, data interpretation.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Portier K, Greer GE, Rokach L, et al. Understanding topics and sentiment in an online cancer Survivor community. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2013;2013:195–8. 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgt025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheung CK, Zebrack B. What do adolescents and young adults want from cancer resources? insights from a Delphi panel of AYA patients. Support Care Cancer 2017;25:119–26. 10.1007/s00520-016-3396-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Attai DJ, Cowher MS, Al-Hamadani M, et al. Twitter social media is an effective tool for breast cancer patient education and support: patient-reported outcomes by survey. J Med Internet Res 2015;17:e188 10.2196/jmir.4721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ben-Aharon I, Goshen-Lago T, Fontana E, et al. Social networks for young patients with cancer: the time for system agility. Lancet Oncol 2019;20:765 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30346-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorman JR, Roberts SC, Dominick SA, et al. A diversified recruitment approach incorporating social media leads to research participation among young Adult-Aged female cancer survivors. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2014;3:59–65. 10.1089/jayao.2013.0031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perales M-A, Drake EK, Pemmaraju N, et al. Social media and the adolescent and young adult (AYA) patient with cancer. Curr Hematol Malig Rep 2016;11:449–55. 10.1007/s11899-016-0313-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gage-Bouchard EA, LaValley S, Warunek M, et al. Is cancer information exchanged on social media Scientifically accurate? J Cancer Educ 2018;33:1328–32. 10.1007/s13187-017-1254-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou L, Zhang D, Yang C, et al. Harnessing social media for health information management. Electron Commer Res Appl 2018;27:139–51. 10.1016/j.elerap.2017.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]