Abstract

Background

The gut microbiota influences many immunological processes but how its disruption affects transplant rejection is poorly understood.

Methods

Interposition grafting of aortic segments was used to examine vascular rejection. The gut microbiota was disrupted in graft recipients using an antibiotic cocktail (ampicillin, vancomycin, metronidazole, neomycin sulfate) in their drinking water.

Results

Treatment of mice with antibiotics severely reduced total bacterial content in the intestine and disrupted the bacterial composition. Short-term treatment of mice for only the first 3 weeks of life resulted in the population of the intestine in mature mice with bacterial communities that were mildly different from untreated mice, containing slightly more Clostridia and less Bacteroides. Antibiotic disruption of the gut microbiota of graft recipients, either for their entire life or only during the first 3 weeks of life, resulted in increased medial injury of allograft arteries that is reflective of acute vascular rejection but did not affect intimal thickening reflective of transplant arteriosclerosis. Exacerbated vascular rejection resulting from disruption of the gut microbiota was related to increased infiltration of allograft arteries by neutrophils.

Conclusions

Disruption of the gut microbiota early in life results in exacerbation of immune responses that cause acute vascular rejection.

The gut microbiota provides antigenic, innate sensing, and metabolic signals that influence the activation of protective and pathological immune responses.1 Specifically, bacterial antigens from species of Clostridia induce regulatory T (Treg) cells that protect against the induction of immunopathology in the intestine and nonintestinal tissues.2 Bacterial antigens also induce Th17 cells that can disseminate systemically to nonintestinal tissues, such as the brain, and exacerbate immunopathology.3 In addition to antigenic signals, stimulation of pattern recognition receptors by microbial components provides innate sensing signals that are important for immune homeostasis and protective immune responses.4–6 Finally, short chain fatty acid (SCFA) metabolites regulate immune responses by inducing Treg cell differentiation and opposing neutrophil activation.7,8 Bacteria from the phylum Firmicutes produce the SCFA butyrate, which induces the differentiation of Treg cells, and Bacteroidetes produce acetate, which dampens pathological neutrophil activation.7–10

Continuous signals provided by the gut microbiota can influence the activation of immune responses, but temporary disruption of this microbial community early in life also leads to persistent immunological changes that increase pathological responses later in life.11 Mice that have had their gut microbiota severely disrupted with antibiotics or that are raised in germ-free environments develop exacerbated neutrophil activation, pathological Th2 and Th17 airway responses as well as altered development of type 1 diabetes.8,12–14 Also, antibiotic exposure and alterations in the composition of the gut microbiota in children is associated with increased risk of developing allergy, asthma, eczema, and metabolic disorders later in life.15–17

The rejection of transplanted organs is an immunologically driven process. Rejection of allograft blood vessels is a prominent feature of both acute and chronic rejection. Leukocyte- and antibody-mediated damage of the microvasculature results in edema and thrombosis that are features of acute rejection. Arteritis, another feature of acute rejection, is characterized by leukocyte infiltration into the subendothelial and medial compartments of allograft arteries.18 In this setting, infiltrating T cells and neutrophils injure medial smooth muscle cells via cytotoxic mechanisms, leading eventually to medial destruction that compromises vasoreactivity.19–22 Chronic immunological targeting of allograft arteries by T cells and antibodies causes transplant arteriosclerosis (TA), which is characterized by thickening of the arterial intima.23,24 Cytokines produced by infiltrating T cells cause the migration and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells in the intima and increases inflammatory activation of endothelial cells that supports further infiltration of leukocytes into the intima.24 Also, T cell-mediated cytotoxicity of the luminal endothelium triggers a vascular reparative response that results in smooth muscle cell migration and proliferation in the intima.25

Little is known about how antibiotic disruption of the gut microbiota may regulate immune responses that lead to graft rejection. Specifically, the effect of disrupting the gut microbiota early in life remains unclear. We addressed this topic using an aortic interposition model of vascular rejection in which there is immune-mediated medial injury reflective of acute vascular rejection and intimal thickening that resembles TA.26 Disruption of the gut microbiota with antibiotics, either for the life of graft recipients or only during the first 3 weeks of life, led to increased medial injury but did not affect the development of intimal thickening. Exacerbated medial injury was related to increased accumulation of neutrophils. These findings show that disruption of the gut microbiota early in life alters the regulation of immune responses that impact acute vascular rejection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Breeding pairs of C57Bl/6 (H-2b) and Balb/c (H-2d) mice were originally purchased from Jackson Laboratories, and then bred in-house and used for experimentation at 8 to 12 weeks of age. All mice were housed in the same room in the same animal facility and were in different cages because antibiotics were administered through the drinking water. Protocols used in the study were approved by the Simon Fraser University Animal Care Committee.

Antibiotic Treatment

Mice were treated with ampicillin (0.5 g/L), vancomycin (0.25 g/L), neomycin sulfate (0.5 g/L), and metronidazole (0.5 g/L) in the drinking water. Pregnant females received antibiotic water ad libitum starting 1 week before giving birth. Pups received antibiotic water from weaning through adulthood ad libitum. In experiments examining the effect of antibiotic exposure early in life, pups received antibiotics until they were 3 weeks of age and then were maintained on normal water thereafter.

Quantification of Bacteria in Fecal Samples

Fecal samples were homogenized, mounted in ProLong Gold (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and photomicrographs taken at 400×. DAPI stained area was quantified using ImageJ (NIH, USA).

Quantification of Fungal DNA in Fecal Samples

Isolated fecal DNA was used as the template for Taqman qPCR using broadly specific primer/probes for the fungal 18S gene.27 Data were acquired on an ABI 7900HT iCycler.

16S Sequencing and Analysis

Fecal samples were collected from mice, either before transplantation or at day 7 after transplantation. Amplification and DNA sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene was performed at the Genome Science Centre in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Detailed description of the 16S sequencing and analyses is provided in the online supplement, SDC (http://links.lww.com/TP/B549).

Flow Cytometric Analysis

Splenocytes were stained with antibodies recognizing CD4 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), CD8 (BD Biosciences), CD44 (BD Biosciences), and Foxp3 (BD Biosciences). Peripheral blood cells were stained using antibodies recognizing CD11b (BD Biosciences) and GR-1 (eBiosciences). Data were acquired on a BD FACS Jazz (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo.

Aortic Interposition Grafting

Aortic interposition grafting was performed as described previously.28,29 Briefly, a section of infrarenal aorta from Balb/c donors was interposed into the infrarenal aorta of C57Bl/6 recipient mice. Aortic segments from C57Bl/6 mice were used as syngraft controls. After 7 or 30 days, arteries were perfusion fixed with 4% (v/v) paraformaldehyde in PBS, excised, and then frozen in optimal cutting temperature medium.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Cross-sections of artery grafts were hematoxylin and eosin–stained and intimal area, luminal area, total cross-sectional area, and medial thickness quantified as described.29 Medial thickness was normalized to arterial radius. Immunohistochemistry was performed and quantified on sections using antibodies to CD4 (Abnova, Taipei City, Taiwan), CD8 (eBiosciences, San Diego, CA), Mac-3 (BD Biosciences), and myeloperoxidase (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) as described.28

Quantification of Serum Levels of Donor-specific Antibody

Balb/c splenocytes were incubated with serum obtained from graft recipients at day 30 posttransplant. Donor-specific antibody binding was detected using a PE conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (eBioscience). Splenocytes were costained for CD3 (BD Biosciences) and the mean fluorescence intensity of donor-specific antibody staining of CD3+ cells quantified. Data were acquired on a BD FACS Jazz and analyzed using FlowJo software (FlowJo, LLC, Ashland, OR).

Statistical Analyses

Differences between groups were determined using a Student t test or analysis of variance followed by a Tukey post hoc test. Significant differences were defined as having an α value less than 0.05.

RESULTS

Immune and Vascular Effects of Disrupting the Gut Microbiota With Antibiotics

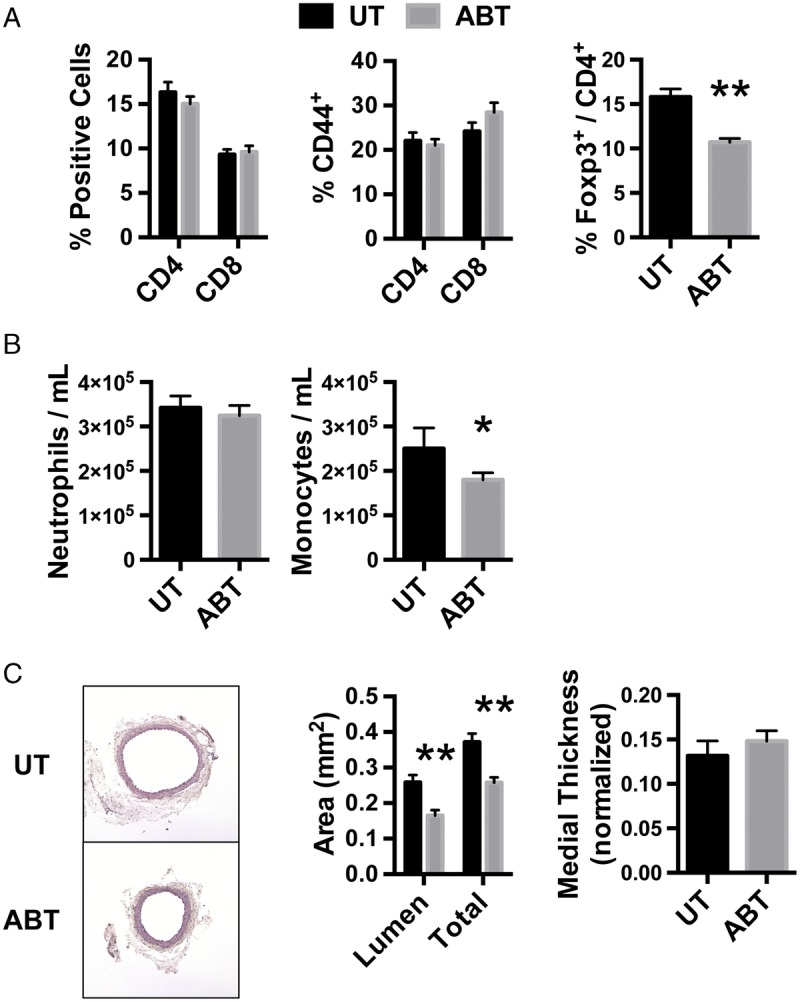

Consistent with previous reports, treatment of mice with a cocktail of antibiotics comprised of ampicillin, vancomycin, neomycin sulfate, and metronidazole significantly reduced DNA content in fecal samples (Fig. S1A, SDC, http://links.lww.com/TP/B549).4,30 Also, there was a low concentration of fungal DNA in fecal samples, and this was not affected by antibiotic treatment (Fig. S1B, SDC, http://links.lww.com/TP/B549). To determine the effect of antibiotics on the baseline immune cell profile in graft recipients, mice were sacrificed between 8 and 12 weeks of age (age range in which transplants are performed), and the composition of immune cells in mice treated with antibiotics was then analyzed. Antibiotic treatment did not affect the frequency of splenic CD4 and CD8 T cells or effector/memory T cells, but Treg cells were significantly reduced in antibiotic-treated (ABT) mice (Figure 1A). There was no effect of antibiotic treatment on the number of circulating neutrophils, but there was a slight reduction in the number of circulating monocytes (Figure 1B). When structural development of the descending aorta was assessed, arteries from ABT mice were structurally similar to untreated counterparts (Figure 1C). There were no vascular lesions or arteriosclerotic changes in mice treated with antibiotics. Orientation of smooth muscle cells in the media was also normal and medial thickness was not different. However, the luminal area and total cross-sectional area of arteries from mice treated with antibiotics was slightly smaller than untreated mice (Figure 1C). Treatment of mice with antibiotics did not result in obvious behavioral changes reflective of dehydration, gastrointestinal distress, or cognitive impairment.

FIGURE 1.

Effect of antibiotic treatment on immune cells and arterial structure. A, Splenocytes were isolated from 8- to 12-week-old UT mice or mice treated with antibiotics for their entire life (ABT) and flow cytometrically analyzed for CD4, CD8, CD44, and Foxp3. Data are the mean ± SEM of the frequency of splenocytes that are CD4 T cells, CD8 T cells, or CD4 and CD8 T cells that are CD44-positive as well as CD4 T cells that are Foxp3-positive (N = 6). B, Cells in the peripheral blood of mice were stained for CD11b and GR-1 to quantify the abundance of neutrophils (CD11b+GR-1+) and monocytes (CD11b+GR-1−). Data are the mean ± SEM of the number of cells. UT (n = 3), ABT (n = 5). C, The abdominal aorta was isolated from UT and ABT mice, and cross-sections stained with H & E. Luminal and total vessel cross-sectional areas as well as thickness of the media were quantified (n = 6). Magnification, 100×, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. UT, untreated.

Effect of Antibiotics on the Gut Microbiota

DNA was isolated from fecal samples taken before aortic interposition grafting and 16S rRNA gene sequencing performed. In addition to administering antibiotics for the entire life of graft recipients, we also examined the gut microbiota in recipients that were given antibiotics for only the first 3 weeks of life. Alteration of the gut microbiota in childhood affects the development of immunopathological conditions in adulthood and treatment of mice for only the first 3 weeks of life provides information related to this situation.15–17

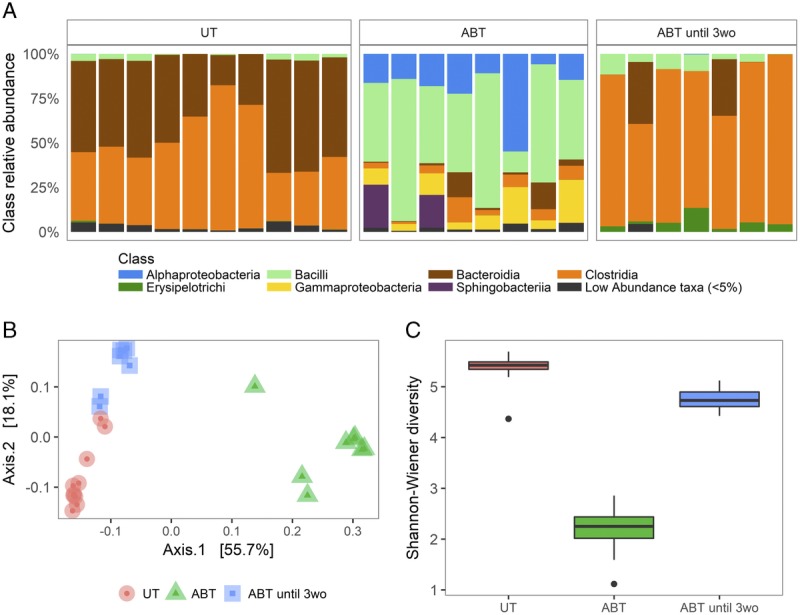

Chloroplast DNA was detected as a significant proportion of 16S reads in mice that were treated with antibiotics for their entire life, reflective of severely reduced gut bacteria content. The amount of chloroplast DNA was comparable between untreated mice and those that were treated with antibiotics for only the first 3 weeks of life, reflective of the population of the intestinal tract with bacteria in these mice. Compositional analysis of the bacterial community showed that antibiotic treatment for the entire life severely altered the taxa of bacteria present (Figure 2A). In mice that received antibiotics for only the first 3 weeks of life, the taxa detected in these mice were comparable to untreated mice, although there was a reduction in Bacteroidia and slight increase in Clostridia. Principal coordinate analysis showed a large difference between untreated mice and mice that received antibiotics for their entire life but the composition of the gut bacteria in mice that received antibiotics for only the first 3 weeks of life was only modestly distinct from untreated mice (Figure 2B). Finally, the bacterial diversity of the gut microbiota is severely reduced by antibiotic treatment (Figure 2C). Bacterial diversity was not different in mice that received antibiotics for only the first 3 weeks of life when compared to untreated counterparts. All together, these observations show that the acute effect of the antibiotic cocktail is an extreme alteration of the gut microbiota and that the gut bacterial community populates after cessation of antibiotics early in life to a composition that is slightly different than untreated mice.

FIGURE 2.

Antibiotic treatment severely alters the composition of the microbiota. A, Relative abundance of bacterial classes in UT mice (n = 10), mice treated with antibiotics for their entire life (ABT, n = 8), and ABT until 3wo (n = 7). B, PCoA plotting similarities among samples based on the composition of gut bacterial communities. C, Comparison of bacterial community complexities (alpha diversity) measured as Shannon-Weiner Diversity Index. The lower and upper box edges correspond to the first and third quartiles, the whiskers extend to the highest and lowest values that are within 1.5 times the interquartile range, and data beyond this limit are plotted as points. PCoA, principal coordinate analysis; ABT until 3wo, mice treated with antibiotics for the first 3 weeks of life.

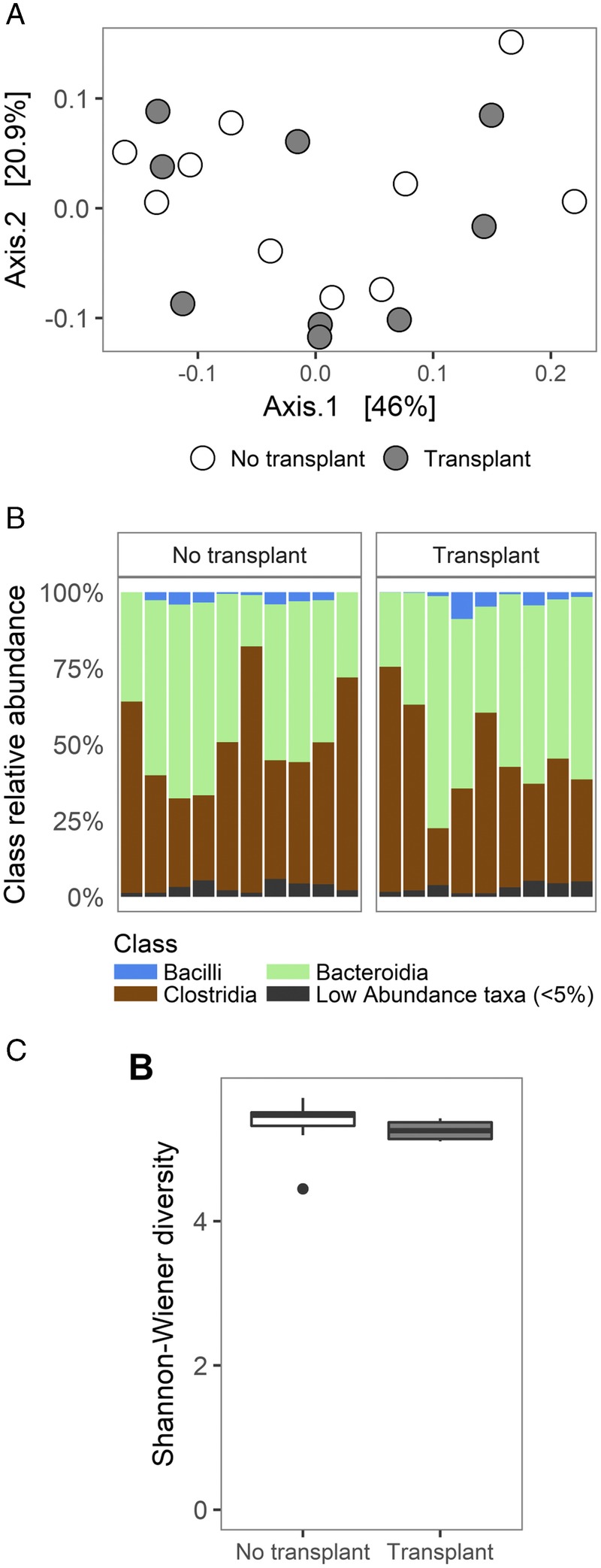

Transplantation Does Not Alter the Gut Microbiota

Composition of the gut microbiota is altered after kidney transplantation.31 It is not known to what extent the transplantation procedure, alloimmune response, or transplant-related drugs contributes to this alteration. To provide insight into this, 16S rRNA gene sequencing was performed on fecal samples from mice that did not or did receive aortic interposition grafts. Principal coordinate analysis indicated that microbial communities in nontransplanted and transplanted recipients did not cluster separately (Figure 3A). The bacterial taxa present in transplant recipients was also comparable to mice that did not receive a transplant (Figure 3B). Diversity of the gut microbiota was not affected by transplantation (Figure 3C). This indicates that the transplantation procedure itself, and subsequent induction of an alloimmune response, does not affect the composition of the gut microbiota.

FIGURE 3.

Transplantation does not affect the composition of the gut microbiota. A, PCoA plot of similarities in the composition of the gut microbiota between mice that did not and did receive an allograft artery. B, Relative abundance of bacterial classes in mice that did not and did receive an allograft artery. C, Comparison of bacterial community complexities (alpha diversity) measured as Shannon-Weiner Diversity Index between mice that did not and did receive an allograft artery.

Disruption of the Gut Microbiota With Antibiotics Early in Life Increases Medial Injury of Allograft Arteries

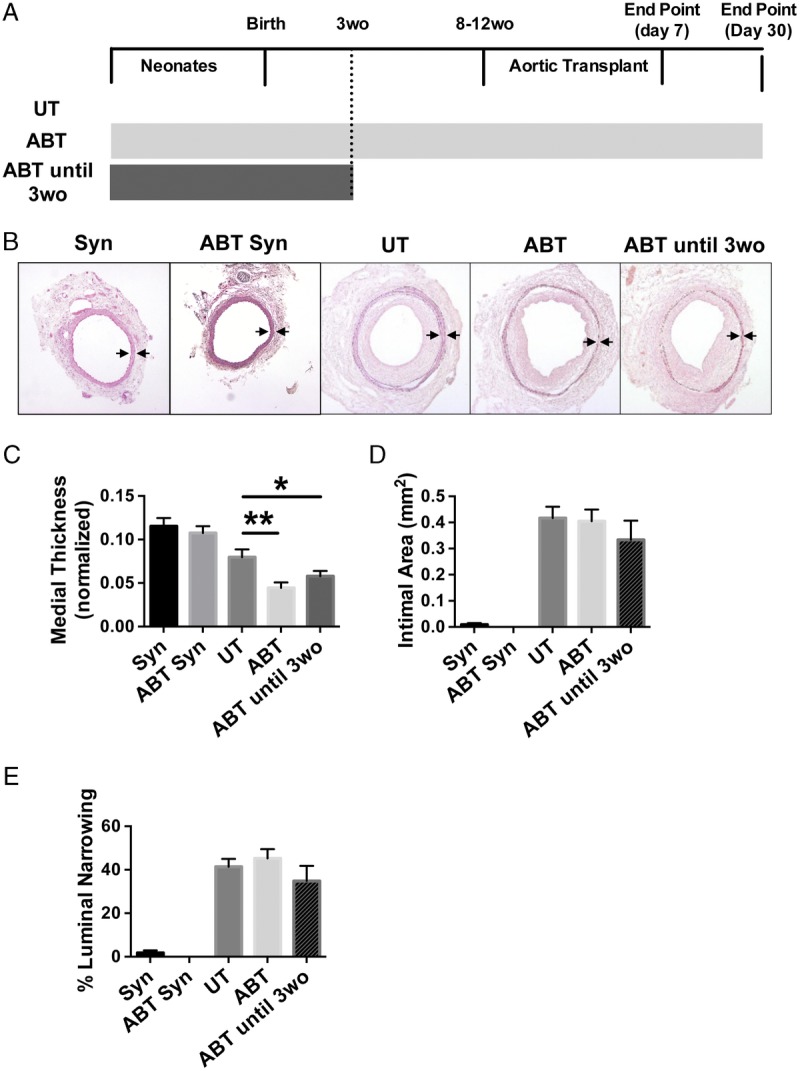

The effect of antibiotics on arterial injury and remodeling that leads to acute vascular rejection and TA was then examined by grafting aortic segments from Balb/c donors into C57Bl/6 recipients that were either untreated or treated with antibiotics. In this model, acute vascular rejection leads to medial injury that can be assessed by quantification of medial thickness, a reduction indicative of increased injury and acute rejection. Intimal hyperplasia is reflective of TA.26 Graft recipients were untreated or treated with antibiotics starting as neonates and then either maintained on antibiotics for their entire life or antibiotics removed and replaced with normal water at 3 weeks of age. In all situations, aortic interposition grafts were performed between 8 and 12 weeks of age and grafts harvested at days 30 and 7 posttransplant. Structural alterations, such as medial degradation and intimal thickening, are abundant and reproducible at day 30 posttransplantation and immune activation is near maximal at day 7 posttransplant (Figure 4A).29,32

FIGURE 4.

Disruption of the gut microbiota with antibiotics increases medial injury. A, Experimental scheme. Graft recipients were untreated, treated with antibiotics for their entire life, or treated with antibiotics for only the first 3 weeks of life. Aortic interposition grafts were implanted into 8- to 12-week-old recipients and grafts harvested at days 30 and 7 posttransplant. B, Representative images of syngrafts (Syn) from recipient mice that were untreated (n = 3) or treated with antibiotics for their entire life (ABT, n = 3), and allograft arteries from recipient mice that were UT (n = 13), ABT (n = 10), or ABT until 3wo (n = 6) harvested at day 30 post-transplantation. A mask has been applied to highlight the medial layer. Magnification, 100×. Arrows denote external and internal elastic lamina borders of the media. C, Quantification of medial thickness of grafts. Mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 **P < 0.01 compared with UT group. D and E, Quantification of (D) intimal area and (E) luminal narrowing in grafts placed into UT, ABT, and ABT until 3wo graft recipients (mean ± SEM).

The structure of artery grafts in the absence of immunological rejection was first determined by examining size-matched syngeneic aortic grafts. Treatment with antibiotics did not affect the size or structure of syngrafted arteries at day 30 after transplantation (Figure 4B and see Figure S2, SDC, http://links.lww.com/TP/B549). The structure and thickness of the media were comparable, and there was no neointimal formation in either group (Figure 4 B-E). Allograft artery segments from graft recipients that were treated with antibiotics for their entire life had significantly reduced medial thickness in comparison to untreated controls. Treatment of graft recipients with antibiotics for only the first 3 weeks of life was sufficient to recapitulate this effect (Figure 4B and C). When intimal thickening was examined, there was no effect of antibiotics on this vascular change reflective of TA (Figures 4D and E). These findings suggest that disruption of the gut microbiota with antibiotics increases acute vascular rejection that exacerbates medial injury of allograft arteries and that disruption of the gut microbiota early in life is sufficient to cause this effect.

Disruption of the Gut Microbiota With Antibiotics Does Not Affect the Induction of Donor-specific Antibodies

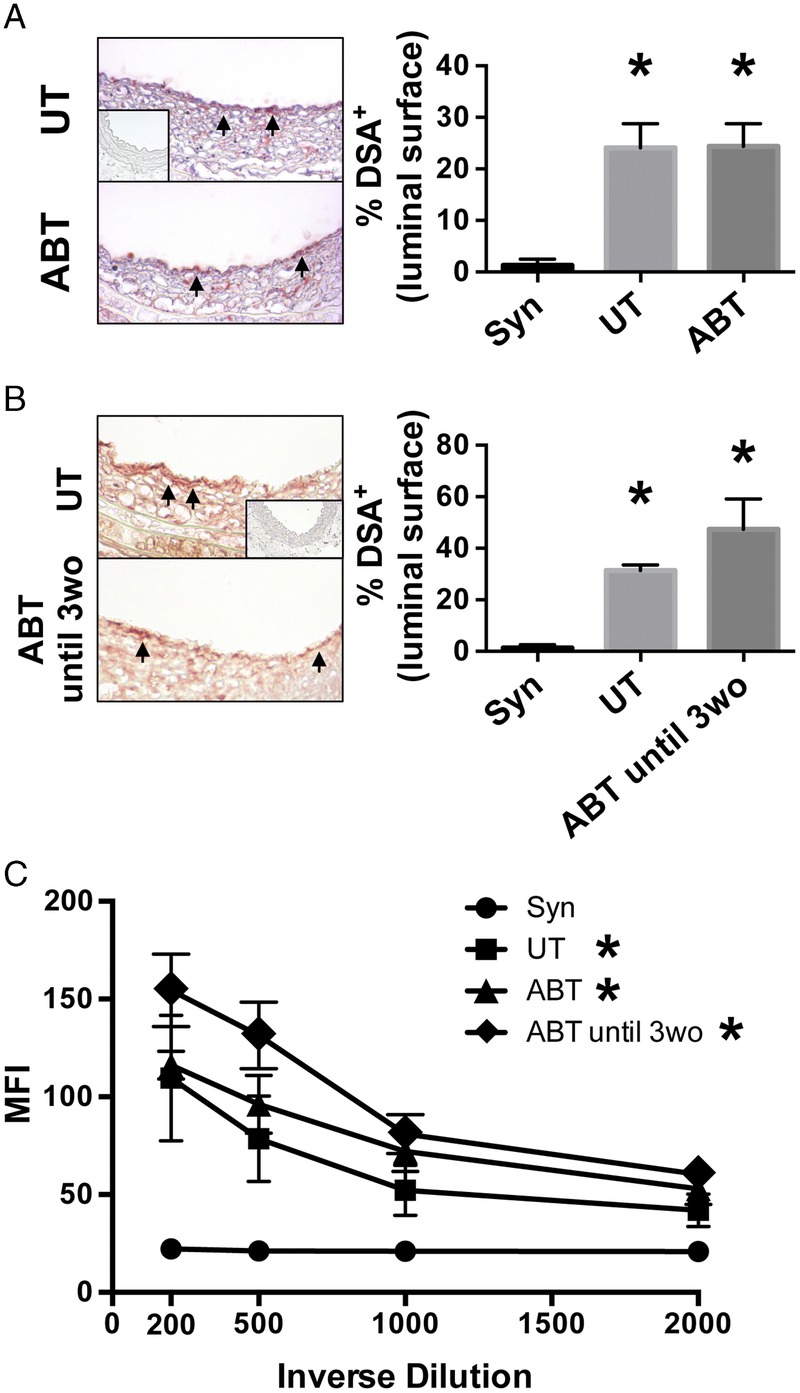

Leukocyte and antibody responses toward allograft arteries are involved in vascular rejection. To examine the latter, the binding of donor-specific antibodies to the luminal endothelial surface of allograft arteries and their presence in the circulation was examined at day 30 posttransplantation. Treatment of graft recipients with antibiotics, either for their entire life or for the first 3 weeks of life, did not affect the abundance of donor-specific antibodies on the luminal surface of allograft arteries or in the circulation of graft recipients (Figure 5, P > 0.26 for untreated compared with ABT for life and P > 0.11 for untreated compared to ABT for first 3 weeks of life).

FIGURE 5.

Disruption of the gut microbiota with antibiotics does not affect the development of donor specific antibodies. A and B, Aortic interposition grafts were harvested at day 30 posttransplantation from recipients that were ABT (A) their entire life and (B) ABT until 3wo. Cross-sections of grafts were immunohistochemically stained for mouse IgG to detect DSA. Arrows indicate positive staining for donor-specific antibodies on the luminal surface. Inset is photomicrograph of syngraft artery. The presence of DSA was quantified by calculating the percentage of luminal surface that was positive. Mean ± SEM is presented. Magnification, 400× (n = 8). *P < 0.05 compared with syngraft recipients. C, DSAs in the serum of graft recipients was quantified. Graph is the mean ± SEM of MFI staining in allogeneic CD3+ cells at different dilutions of serum. *P < 0.05 compared to syngraft recipients. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; DSA, donor-specific antibodies.

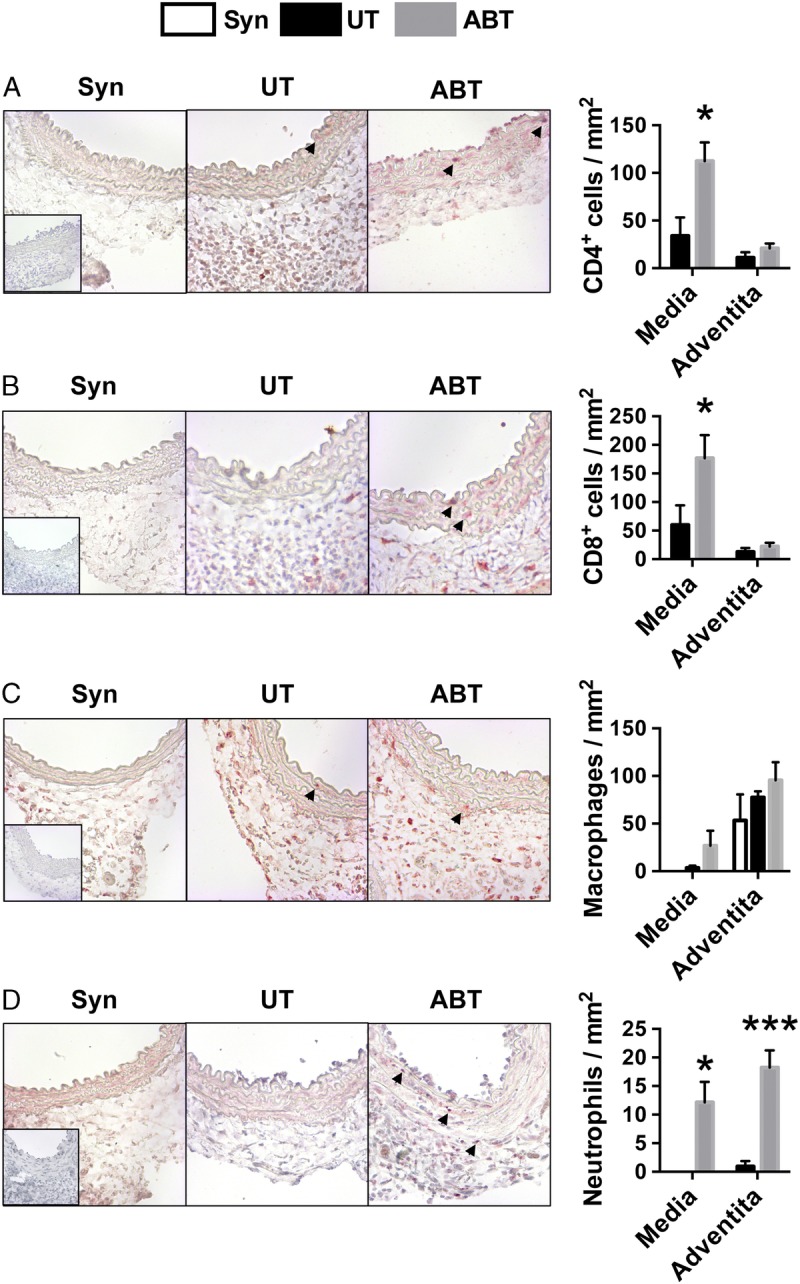

Disruption of the Gut Microbiota With Antibiotics for the Entire Life of Graft Recipients Increases T Cell and Neutrophil Accumulation in Allograft Arteries

Morphological changes in arteries late after transplantation at day 30 after surgery suggests that antibiotic disruption of the gut microbiota exacerbates acute vascular rejection that damages the media. Because these changes at day 30 after transplantation reflect damage and subsequent reparative responses of the artery, we examined the accumulation of leukocytes in transplanted aortic segments at day 7 after transplantation. No leukocytes were present in syngraft controls, except for some macrophages that were in the adventitia of all grafts. Treatment of graft recipients with antibiotics for their entire life markedly and significantly increased CD4 and CD8 T-cell accumulation in the media of artery grafts (Figures 6A and B). Antibiotic treatment of graft recipients also appeared to increase macrophage accumulation within the media of allograft arteries, but this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.16, Figure 6C). No neutrophils were observed in either the media or adventitia of allograft arteries in untreated recipients but antibiotic treatment led to a dramatic and significant induction of neutrophil accumulation in both regions of the allograft artery (Figure 6D). B and NK cells were infrequent in allograft arteries, and this was not affected by disruption of the gut microbiota (Figure S3, SDC, http://links.lww.com/TP/B549). Overall, disruption of the gut microbiota in graft recipients resulted in increased infiltration of T cells and neutrophils into the media of allograft arteries early after transplantation, which is reflective of an acute rejection process.33

FIGURE 6.

Disruption of the gut microbiota with antibiotics increases immune cell accumulation in allograft arteries early after transplantation. Aortic segments were interposition grafted from Balb/c donors into C57Bl/6 recipients that were UT (n = 5) or ABT for their entire life (n = 8). Syngrafts (Syn, N = 3) served as controls. Grafts were harvested at day 7 posttransplantation and cross-sections immunohistochemically stained for (A) CD4 to visualize CD4 T cells, (B) CD8 to visualize CD8 T cells, (C) Mac-3 to visualize macrophages, and (D) myeloperoxidase to visualize neutrophils. Staining was quantified and the mean ± SEM is presented. Arrows denote positively stained cells. Insets are photomicrographs of isotype staining controls. Magnification, 400×. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

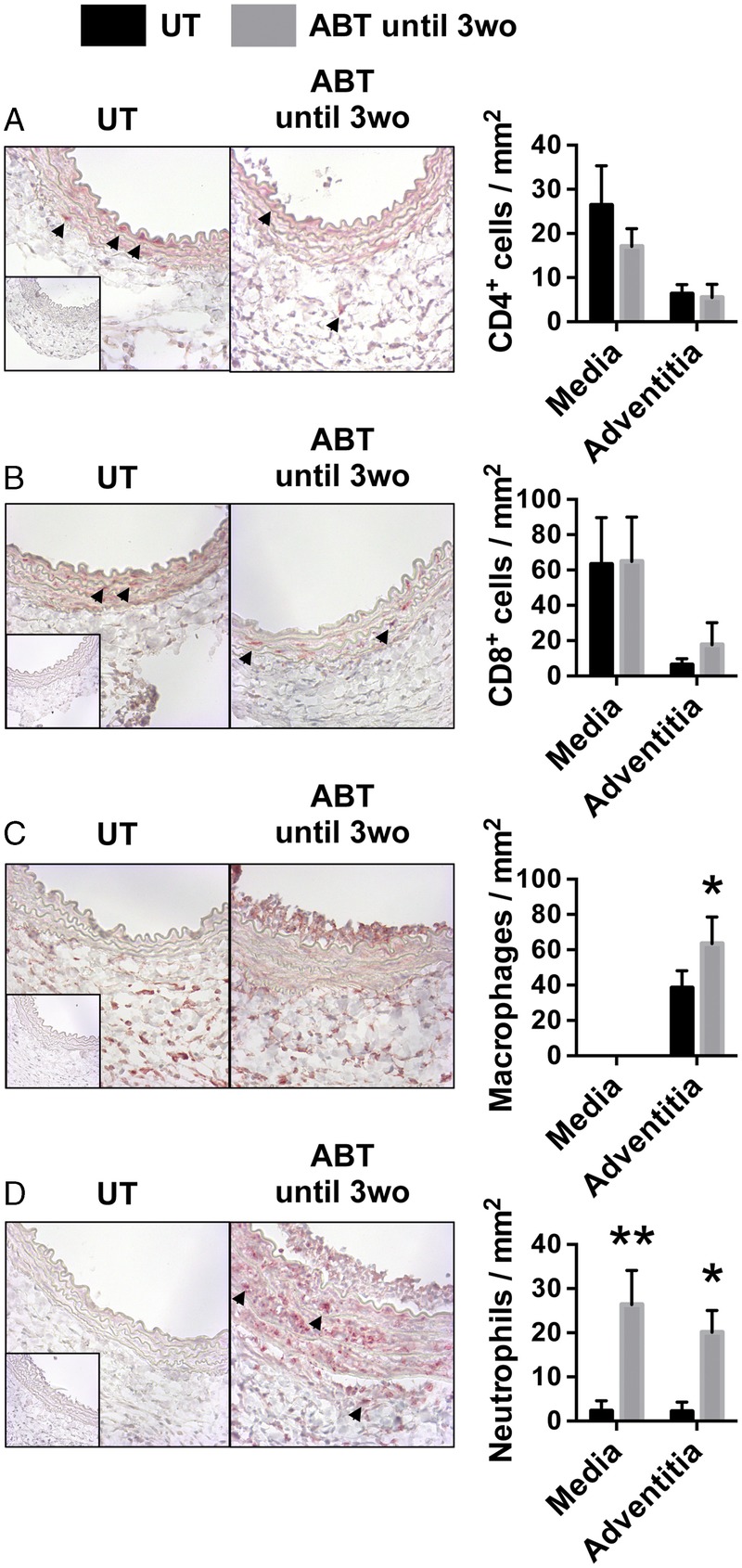

Disruption of the Gut Microbiota Early in Life Increases Neutrophil Accumulation in Allograft Arteries

We also examined the immunological effect of disrupting the microbiota for a short period after birth. At day 7 posttransplantation, grafts from mice that were treated with antibiotics for only the first 3 weeks of life had similar levels of CD4 and CD8 T-cell accumulation as compared with untreated counterparts (Figure 7A and B). There was a slight increase in macrophage accumulation in the adventitia of arteries from mice that were treated with antibiotics for only the first 3 weeks of life (Figure 7C). Strikingly, there was a marked and significant increase in neutrophil accumulation in arteries from mice that were treated with antibiotics for only the first 3 weeks of life as compared with untreated recipients. The magnitude of neutrophil accumulation was similar to that observed in graft recipients that were treated with antibiotics for their entire life (Figure 7D). Also, similar to animals that were treated with antibiotics for their entire life, disruption of the gut microbiota early in life did not increase the abundance of neutrophils in the circulation (Figure S4, SDC, http://links.lww.com/TP/B549). This indicates that disruption of the gut microbiota with antibiotics early in life leads to a persistent effect in mature mice that exacerbates neutrophil responses toward allograft arteries.

FIGURE 7.

Disruption of the gut microbiota with antibiotics early in life increases neutrophil accumulation in allograft arteries. Aortic segments were interposition grafted from Balb/c donors into C57Bl/6 recipients that were UT (n = 5) or ABT until 3wo (n = 7). Grafts were harvested at day 7 posttransplantation and cross-sections immunohistochemically stained for (A) CD4 to visualize CD4 T cells, (B) CD8 to visualize CD8 T cells, (C) Mac-3 to visualize macrophages, and (D) myeloperoxidase to visualize neutrophils. Staining was quantified and the mean ± SEM is presented. Arrows denote positively stained cells. Magnification, 400×. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Our studies show that disruption of the gut microbiota with antibiotics in graft recipients leads to immune dysregulation that excerbates acute vascular rejection. Exposure to antibiotics early in life is sufficient to cause this effect. These findings may have implications for understanding how environmental exposures that alter the gut microbiota could impact the development of immune responses in transplantation.

The composition of the gut microbiota is altered in kidney graft recipients after transplantation.31 Also, differences in the composition of the gut microbiota are associated with increased acute rejection, posttransplant diarrhea, and dosing of immunosuppressive drugs.34,35 The causal factors driving these alterations and differences are not known. We have found that transplantation in the absence of immunosuppressive drugs does not affect the composition of the gut microbiota. As such, the transplant procedure itself and/or active induction of an alloimmune response towards nonintestinal tissues may not cause changes in the composition of this microbial community and changes observed in patients could be driven by the actions of transplant-related drugs.

Disruption of the gut microbiota with antibiotics resulted in slight differences in baseline immune and vascular features in graft recipients. The reduction in circulating monocytes that we observe is consistent with other reports.36 Also, there was a slight reduction in lumen size of the aorta in mice given antibiotics for their entire life. The reason for this is unclear but SCFAs produced by the microbiota can affect blood pressure through effects on the renin-angiotensin system and on vascular smooth muscle cell function.37 The gut microbiota also supports maturation of the intestinal vasculature.38 Importantly, antibiotics had no effect on size-matched syngraft controls, indicating that its exacerbation of vascular rejection was due to the effects on immune activation.

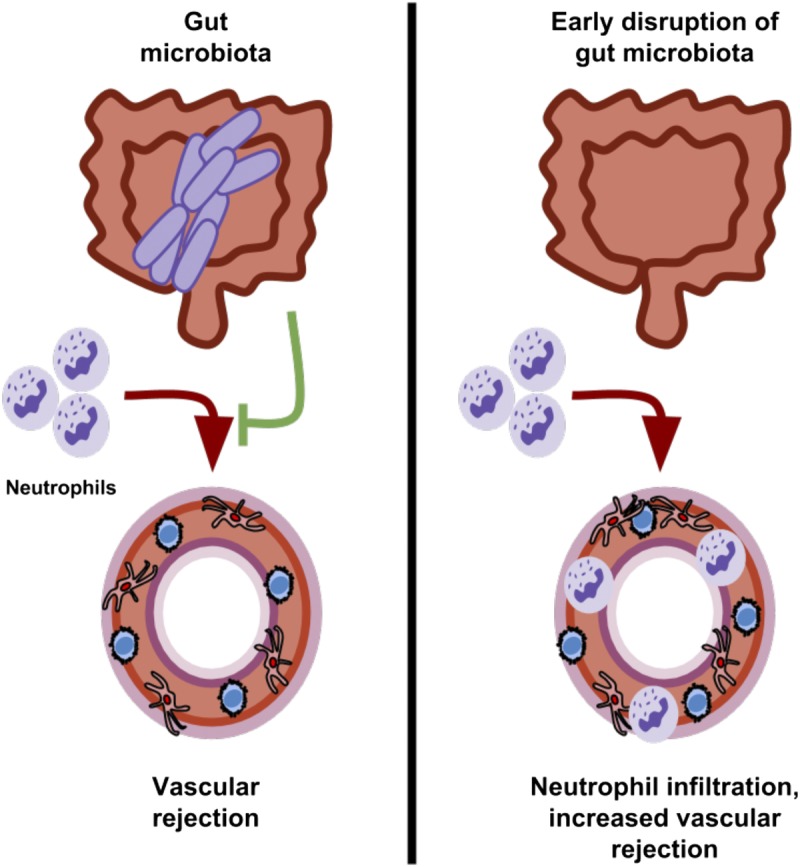

Although ablation of the bacterial content in the intestinal tract provides useful information on the biological role of these microbes, health implications are likely to be more closely related to short-term alterations in the gut bacterial community. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota in children may result from antibiotic treatment of bacterial infections that subtly alter the composition of this microbial community or that could lead to more substantial changes in high-risk infants that experience complications during and after birth. The composition of the gut microbiota is also affected by diet.39 These environmental factors may cause changes in the gut microbiota early in life that influence immunological events later in life. Indeed, disruption of the gut microbiota early in life in experimental models is sufficient to increase disease susceptibility to allergy, asthma, and inflammatory bowel disease.13,40,41 Also, early changes in the composition of the gut microbiota in children are associated with increased susceptibility to allergy and asthma later in life.15–17 Here, we find that disruption of the gut microbiota with antibiotics early in life increases acute vascular rejection. The mechanism by which this occurs may relate to increased infiltration of the vascular grafts by neutrophils (Figure 8). Indeed, neutrophils are known to contribute to early medial injury of allograft arteries as well as acute rejection of heart transplants.21,42,43 Further, production of acetate by Bacteroidetes bacteria inhibits neutrophil activation, and we observe a persistent reduction in bacteria from this phylum in adult mice that were treated with antibiotics early in life.8 Exacerbated vascular injury in graft recipients that only received antibiotics early in life also suggests that our findings are not a result of off-target effects of antibiotics since these drugs are cleared from the circulation by the time of transplantation in these experiments.

FIGURE 8.

Disruption of the gut microbiota early in life exacerbates acute vascular rejection. The gut microbiota provides signals that regulate acute rejection of allograft arteries. Disruption of the gut microbiota early in life leads to immune dysregulation that increases neutrophil accumulation in allograft arteries and acute vascular rejection.

Acute vascular rejection was increased by disruption of the gut microbiota but there was no effect on intimal thickening, a feature of TA. Although arteritis is associated with later development of TA, each condition also has distinct pathological features that may lead to a specific effect on acute rejection but not TA.23,26,44 Aortic interposition grafting across the strain combinations we have used provides comprehensive information on the immunopathological mechanisms of acute arterial rejection.26 Development of intimal thickening in this model results from the intimal migration and proliferation of medial smooth muscle cells and circulating vascular progenitor cells.45 This differs from intimal thickening in clinical samples of TA, which results mostly from the migration and proliferation of medial smooth muscle cells with limited contribution of circulating progenitors.46

Future experiments will elucidate whether increased neutrophil infiltration or dietary modification of the gut microbiota can prevent acute vascular rejection caused by disruption of gut bacteria early in life. This could involve depletion of neutrophils in graft recipients before transplantation and/or assessment of vascular rejection in graft recipients that lack GPR43, a membrane receptor needed for attenuation of neutrophil activation by acetate produced by the gut microbiota.8 Alternative approaches to examine the mechanisms by which disruption of the gut microbiota exacerbates rejection may involve systemic administration of SCFAs or dietary modifications that attenuate neutrophil activation.47,48

Lei et al49 reported that reducing microbe-derived signals ablating or eliminating the microbiota in both graft donors and recipients shortly before transplantation attenuates the activation of alloreactive T cells by antigen-presenting cells and prolongs organ transplant survival. On the other hand, Alhabbab et al50 showed that microbial signals from the microbiota can induce the differentiation of regulatory B cells that prevent skin transplant rejection through an IL-10-dependent mechanism. These findings have implications for understanding how modulation of the microbiota around the time of transplantation may affect graft outcome. We have shown that disruption of the gut microbiota early in life results in persistent immune dysregulation later in life that increases acute vascular rejection. Our findings have implications for understanding the persistent effect of disrupting the gut microbiota in childhood and potentially on how the gut microbiota may impact immunosuppressive approaches that involve immune ablation followed by redevelopment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to Ms. Mary Dearden, Kim Buettner, and Susan Riviere for expert assistance with animal care. The authors also thank the technical staff at Canada’s Michael Smith Genome Sciences Centre for assistance with 16S sequencing.

Footnotes

This work was supported by funding from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (J.C.C.), Genome Canada and AllerGen NCE (F.S.L.B.), and Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (T.V.R.). J.C.C. and R.D.M. are recipients of Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Scholar awards.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

K.R., T.V., K.B., R.D.M., F.S.L.B., and J.C.C. designed the experiments. K.R., S.M., W.E., T.V., and K.B. performed the experiments. K.R., S.M., T.V., K.B., R.D.M., F.S.L.B., and J.C.C. analyzed and interpreted the data. K.R., T.V., K.B., R.D.M., F.S.L.B., and J.C.C. wrote the article.

Correspondence: Jonathan Choy, PhD, Department of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry, Simon Fraser University, 8888 University Drive, Burnaby, BC, Canada V5A 1S6. (jonathan.choy@sfu.ca).

Supplemental digital content (SDC) is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text, and links to the digital files are provided in the HTML text of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.transplantjournal.com).

Disruption of mice gut microbiota, either for their entire life or only during the first 3 weeks of life, results in increased acute vascular rejection of allograft arteries due to infiltration of the media by neutrophils. Intima thickening of the arteries reflecting chronic rejection is not affected. Supplemental digital content is available in the text.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gensollen T, Iyer SS, Kasper DL. How colonization by microbiota in early life shapes the immune system Science 2016. 352539–544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Oshima K. Treg induction by a rationally selected mixture of Clostridia strains from the human microbiota Nature 2013. 500232–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazmanian SK, Liu CH, Tzianabos AO. An immunomodulatory molecule of symbiotic bacteria directs maturation of the host immune system Cell 2005. 122107–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis Cell 2004. 118229–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ganal SC, Sanos SL, Kallfass C. Priming of natural killer cells by nonmucosal mononuclear phagocytes requires instructive signals from commensal microbiota Immunity 2012. 37171–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abt MC, Osborne LC, Monticelli LA. Commensal bacteria calibrate the activation threshold of innate antiviral immunity Immunity 2012. 37158–170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells Nature 2013. 504446–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maslowski KM, Vieira AT, Ng A. Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor GPR43 Nature 2009. 4611282–1286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.den Besten G, van Eunen K, Groen AK. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism J Lipid Res 2013. 542325–2340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arpaia N, Campbell C, Fan X. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation Nature 2013. 504451–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vangay P, Ward T, Gerber JS. Antibiotics, pediatric dysbiosis, and disease Cell Host Microbe 2015. 17553–564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill DA, Siracusa MC, Abt MC. Commensal bacteria-derived signals regulate basophil hematopoiesis and allergic inflammation Nat Med 2012. 18538–546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Russell SL, Gold MJ, Reynolds LA. Perinatal antibiotic-induced shifts in gut microbiota have differential effects on inflammatory lung diseases J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015. 135100–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wen L, Ley RE, Volchkov PY. Innate immunity and intestinal microbiota in the development of Type 1 diabetes Nature 2008. 4551109–1113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arrieta MC, Stiemsma LT, Dimitriu PA. Early infancy microbial and metabolic alterations affect risk of childhood asthma. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:307ra152. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujimura KE, Sitarik AR, Havstad S. Neonatal gut microbiota associates with childhood multisensitized atopy and T cell differentiation Nat Med 2016. 221187–1191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia-Marcos L, Gonzalez-Diaz C, Garvajal-Uruena I. Early exposure to paracetamol or to antibiotics and eczema at school age: modification by asthma and rhinoconjunctivitis Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2010. 211036–1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart S, Winters GL, Fishbein MC. Revision of the 1990 working formulation for the standardization of nomenclature in the diagnosis of heart rejection J Heart Lung Transplant 2005. 241710–1720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tellides G, Pober JS. Inflammatory and immune responses in the arterial media Circ Res 2015. 116312–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.So M, Lee TD, Hancock Friesen CL. Neutrophils are responsible for impaired medial smooth muscle cell recovery and exaggerated allograft vasculopathy in aortic allografts exposed to prolonged cold ischemia J Heart Lung Transplant 2013. 32360–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King CL, Devitt JJ, Lee TD. Neutrophil mediated smooth muscle cell loss precedes allograft vasculopathy. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;5:52. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-5-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moien-Afshari F, Choy JC, McManus BM. Cyclosporine treatment preserves coronary resistance artery function in rat cardiac allografts J Heart Lung Transplant 2004. 23193–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Rossum A, Laher I, Choy JC. Immune-mediated vascular injury and dysfunction in transplant arteriosclerosis. Front Immunol. 2014;5:684. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pober JS, Jane-wit D, Qin L. Interacting mechanisms in the pathogenesis of cardiac allograft vasculopathy Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2014. 341609–1614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choy JC. Granzymes and perforin in solid organ transplant rejection Cell Death Differ 2010. 17567–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mennander A, Paavonen T, Hayry P. Intimal thickening and medial necrosis in allograft arteriosclerosis (chronic rejection) are independently regulated Arterioscler Thromb 1993. 131019–1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu CM, Kachur S, Dwan MG. FungiQuant: a broad-coverage fungal quantitative real-time PCR assay. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:255. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.von Rossum A, Enns W, Shi P. Bim regulates alloimmune-mediated vascular injury through effects on T-cell activation and death Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2014. 341290–1297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.von Rossum A, Rey K, Enns W. Graft-derived IL-6 amplifies proliferation and survival of effector T cells that drive alloimmune-mediated vascular rejection Transplantation 2016. 1002332–2341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hill DA, Hoffmann C, Abt MC. Metagenomic analyses reveal antibiotic-induced temporal and spatial changes in intestinal microbiota with associated alterations in immune cell homeostasis Mucosal Immunol 2010. 3148–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fricke WF, Maddox C, Song Y. Human microbiota characterization in the course of renal transplantation Am J Transplant 2014. 14416–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mennander A, Tiisala S, Halttunen J. Chronic rejection in rat aortic allografts. An experimental model for transplant arteriosclerosis Arterioscler Thromb 1991. 11671–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang JL, Subbotin VM, Antonysamy MA. Interleukin-17 antagonism inhibits acute but not chronic vascular rejection Transplantation 2001. 72348–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee JR, Muthukumar T, Dadhania D. Gut microbial community structure and complications after kidney transplantation: a pilot study Transplantation 2014. 98697–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee JR, Muthukumar T, Dadhania D. Gut microbiota and tacrolimus dosing in kidney transplantation. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0122399. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mohle L, Mattei D, Heimesaat MM. Ly6C(hi) monocytes provide a link between antibiotic-induced changes in gut microbiota and adult hippocampal neurogenesis Cell Rep 2016. 151945–1956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pluznick JL, Protzko RJ, Gevorgyan H. Olfactory receptor responding to gut microbiota-derived signals plays a role in renin secretion and blood pressure regulation Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013. 1104410–4415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stappenbeck TS, Hooper LV, Gordon JI. Developmental regulation of intestinal angiogenesis by indigenous microbes via Paneth cells Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002. 9915451–15455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harusato A, Chassaing B. Insights on the impact of diet-mediated microbiota alterations on immunity and diseases. Am J Transplant. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Russell SL, Gold MJ, Hartmann M. Early life antibiotic-driven changes in microbiota enhance susceptibility to allergic asthma EMBO Rep 2012. 13440–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miyoshi J, Bobe AM, Miyoshi S. Peripartum antibiotics promote gut dysbiosis, loss of immune tolerance, and inflammatory bowel disease in genetically prone offspring Cell Rep 2017. 20491–504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shimizu K, Shichiri M, Libby P. Th2-predominant inflammation and blockade of IFN-gamma signaling induce aneurysms in allografted aortas J Clin Invest 2004. 114300–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.El-Sawy T, Belperio JA, Strieter RM. Inhibition of polymorphonuclear leukocyte-mediated graft damage synergizes with short-term costimulatory blockade to prevent cardiac allograft rejection Circulation 2005. 112320–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakagawa T, Sukhova GK, Rabkin E. Acute rejection accelerates graft coronary disease in transplanted rabbit hearts Circulation 1995. 92987–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson P, Carpenter M, Hirsch G. Recipient cells form the intimal proliferative lesion in the rat aortic model of allograft arteriosclerosis Am J Transplant 2002. 2207–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Minami E, Laflamme MA, Saffitz JE. Extracardiac progenitor cells repopulate most major cell types in the transplanted human heart Circulation 2005. 1122951–2958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vieira AT, Macia L, Galvao I. A role for gut microbiota and the metabolite-sensing receptor GPR43 in a murine model of gout Arthritis Rheumatol 2015. 671646–1656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vieira AT, Galvao I, Macia LM. Dietary fiber and the short-chain fatty acid acetate promote resolution of neutrophilic inflammation in a model of gout in mice J Leukoc Biol 2017. 101275–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lei YM, Chen L, Wang Y. The composition of the microbiota modulates allograft rejection J Clin Invest 2016. 1262736–2744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alhabbab R, Blair P, Elgueta R. Diversity of gut microflora is required for the generation of B cell with regulatory properties in a skin graft model. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11554. doi: 10.1038/srep11554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]