Abstract

Background

The hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) target pathway plays pivotal renoprotective roles after acute kidney injury. Syndecan-1 (SDC-1) serves as the coreceptor for HGF. Shedding of SDC-1 is involved in various pathological processes. Thus, we hypothesized that ischemia/reperfusion injury induced SDC-1 shedding, and inhibiting SDC-1 shedding would protect against kidney injury by potentiating activation of the HGF receptor mesenchymal epithelial transition factor (c-Met).

Methods

Expression of SDC-1 and its sheddases were observed in kidneys of sham and ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) mice. To inhibit SDC-1 shedding, mice were injected with the sheddase inhibitor GM6001 before I/R surgery, and then, renal inflammation, tubular apoptosis, and activation of the c-Met/AKT/glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) pathway were analyzed. In vitro, human proximal tubular cell lines were pretreated with GM6001 under hypoxia/reperfusion conditions. The apoptosis and viability of cells and expression of c-Met/AKT/GSK-3β pathway components were evaluated. The relationship was further confirmed by treatment with SU11274, a specific inhibitor of phospho-c-Met.

Results

Shedding of SDC-1 was induced after ischemia/reperfusion injury both in vivo and in vitro. GM6001 pretreatment suppressed SDC-1 shedding, alleviated renal inflammation and tubular apoptosis, and upregulated phosphorylation of the c-Met/AKT/GSK-3β pathway. In vitro, pretreatment with GM6001 also decreased hypoxia/reperfusion-induced cell apoptosis and promoted activation of the c-Met pathway. In addition, the cytoprotective role of GM6001 was attenuated by suppressing c-Met phosphorylation with SU11274.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that inhibiting I/R-induced SDC-1 shedding protected against ischemic acute kidney injury by potentiating the c-Met/AKT/GSK-3β pathway.

Acute kidney injury (AKI), characterized by a rapid decline in renal function, is a severe complication associated with high morbidity and mortality.1 Renal ischemia/reperfusion injury (IRI), which is one of the leading causes of AKI, leads to various harmful effects, such as renal inflammation and tubular cell apoptosis.2–4 The process of renal IRI is complicated, and morphological and functional damage to the kidney occurs in the ischemic phase and is further aggravated during reperfusion.5 Although many studies have focused on the pathogenesis of ischemia/reperfusion (I/R)-induced AKI, early effective diagnostic and therapeutic measures are still limited.6

Syndecan-1 (SDC-1) is a cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycan that is predominately expressed by epithelial cells.7 It is composed of a transmembrane core protein and glycosaminoglycan (GAG) side chains, which are attached to the ectodomain of the core protein.8 The GAG chains of SDC-1 act as binding sites for various ligands, such as cytokines, chemokines,9,10 and growth factors.11,12 Previous studies have demonstrated that matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)713,14 and other proteases, such as MMP915 and ADAM17,16 are known to participate in the proteolysis of SDC-1 ectodomain. Syndecan-1 and its shedding are involved in various biological processes, including wound healing,17,18 inflammation,19–21 and tumor progression.22 Recent studies have also revealed important roles of SDC-1 in various renal diseases.16,23–27 Adepu et al16 found that the activation of tubular SDC-1 expression alleviated incipient renal transplant dysfunction. Downregulation of SDC-1 aggravated damage to glomerular endothelial cells in AKI.25 In addition, elevated serum SDC-1 is a potential biomarker to predict renal function and mortality in acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) patients26 and in patients with AKI after pediatric cardiovascular surgery.24 However, a limited number of studies have focused on the effect of SDC-1 shedding in AKI.

Syndecan-1 can facilitate presentation of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) to its specific receptor mesenchymal epithelial transition factor (c-Met) after binding of HGF to GAG chains.12,28 Hepatocyte growth factor is known to play a protective role in various injury models.29,30 Activated c-Met triggers signal transduction cascades to mediate the biological function of HGF.31 Many studies have suggested that HGF/c-Met and its downstream effectors, such as AKT and glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β), are renoprotective in various renal diseases, including AKI,32 diabetic nephropathy,33 and glomerulonephritis.34

Thus, we hypothesize that shedding of SDC-1 may be one of the important mechanisms of tubular epithelial injury after ischemia and hypoxia treatment through downregulating the c-Met/AKT/GSK-3β signaling pathway. To test this hypothesis, we investigated the effects of SDC-1 shedding on renal IRI and explored the underlying mechanism. We found that I/R promoted SDC-1 shedding and that shedding inhibition attenuated tubular epithelial cell (TEC) apoptosis and renal inflammation in IRI by facilitating c-Met signaling. Our findings suggest new potential therapeutic measures for AKI.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and Antibodies

Information regarding the reagents and antibodies used in this study is listed in supplemental materials (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Reagents and materials

Animal Studies

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Fudan University and complied with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Male C57BL/6 mice, 8 to 12 weeks of age and weighing 18 to 22 g, were purchased from Animal Center of Fudan University, Shanghai, China. All mice were fed with standard water and rodent food and kept under routine vivarium conditions.

The mice were randomly divided into 3 groups: a sham group, I/R group, and I/R + GM6001 group (n = 6 in each group). The mice of the I/R group were subjected to renal ischemia-reperfusion surgery as previously described.35 Briefly, bilateral renal pedicles were clamped for 35 minutes, the clamps were then removed to recover renal blood perfusion for 24 hours. Body temperature was controlled at 36.5°C to −37.5 °C. The sham group experienced the same surgical procedure, except the pedicles were not clamped. The mice in the I/R + GM6001 group were intraperitoneally injected with GM6001 (100 mg/kg) 18 hours before the surgery. Kidneys and blood samples were collected for further study.

Cell Culture and Treatments

A human proximal tubular cell line (HK-2) was obtained from American Type Culture Collection and cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Media/Nutrient Mixture F-12 supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum within a humidified chamber with 5% CO2 at 37°C. HK-2 cells were subjected to hypoxic conditions (1% O2, 94% N2, 5% CO2) for 6 hours and then transferred to a normoxic atmosphere (21% O2) for 30 minutes to simulate IRI in vitro. Cells were pretreated with GM6001 (5, 10, 20, 50, or 100 μM) 1 hour before hypoxia to inhibit the activity of MMPs. SU11274 (1, 5, or 10 μM) was added 18 hours before hypoxia/reperfusion (H/R) for c-Met phosphorylation inhibition.

Western Blotting

Protein from HK-2 cells and renal tissues was extracted using RIPA buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Equal amounts of protein (40 μg/lane) were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and then transferred to PVDF membranes. The membranes were incubated with primary antibodies (against SDC-1, MMP7, B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl2)–associated X (Bax), Bcl2, total caspase-3, cleaved caspase-3, total c-Met, phospho-c-Met, total AKT, phospho-AKT, total GSK-3β, phospho-GSK-3β and GAPDH) overnight at 4°C. The blots were then incubated with secondary antibodies and inspected using enhanced chemiluminescence substrate.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from harvested cells or renal tissue with Trizol and reverse transcribed into cDNA with PrimeScript reverse transcription Master Mix. The qRT-PCR analysis was performed using SYBR Premix Ex Taq on a 7500 real-time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). The PCR primer sequences are listed in supplemental materials (Table 1).

Measurement of Serum Creatinine

Serum creatinine levels were determined with a QuantiChrom Creatinine Assay Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Histopathological Examination and Immunohistochemical Staining

After fixation with 10% formalin, hemisected kidneys were embedded in paraffin wax and cut into 4-μm-thick sections for Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining or immunohistochemical staining.

After the sections were stained with PAS kits, histopathological scores of the sections were evaluated using light microscopy (×200 magnification, Leica DM 6000B; Leica Microsystems, Wetzeler, Germany) and determined by the percentage of damaged tubules as follows: no injury (0), mild: less than 25% (1), moderate: less than 50% (2), severe: less than 75%, and (3) very severe: more than 75% (4).

Immunostaining for SDC-1, MMP7, lymphocyte antigen 6G (LY6G), and F4/80 was conducted. Briefly, the dewaxed and rehydrated sections were incubated with the primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Then the sections were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies, visualized with DAB, and counterstained with hematoxylin. All slides were evaluated under light microscopy.

TUNEL Assay

To detect cell apoptosis in kidney sections, TUNEL assays were performed using an In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The TUNEL-positive cells were counted under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX51, Japan) at a magnification of 400 from 6 random fields on each slide.

Flow Cytometry

Annexin V-dimethyl sulfoxide (FITC)/propidium iodide (PI) double staining was performed with HK-2 cells to evaluate apoptosis according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, cells were harvested and incubated with 5 μL of Annexin V-FITC for 15 minutes. Next, PI staining was performed. Cell apoptosis was analyzed immediately via flow cytometry (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay

The concentration of SDC-1 in the serum and HK-2 cell culture medium and the levels of interleukin (IL)-6, IL-10 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α in serum and renal tissue were examined using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cell Viability Assay

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK8) was used to evaluate cell viability. HK-2 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 5 × 103 cells/well and treated according to our experimental protocol. Ten microliters of CCK8 solution was then added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. The absorbance was detected at 450 nm using a spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Statistical Analysis

SPSS 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for statistical analyses. Comparisons between 2 groups were performed using 2-tailed, unpaired t tests. One-way analysis of variance was used for comparisons among multiple groups. The data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. P less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

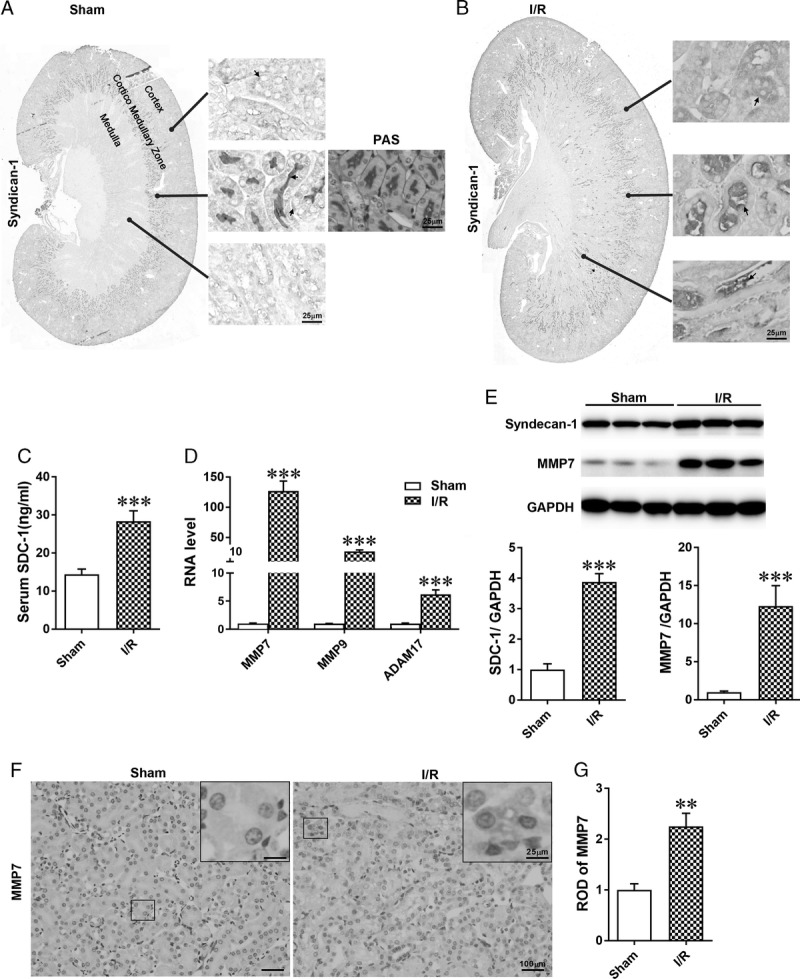

IRI-Induced Shedding of SDC-1 in the Kidneys of Mice

To investigate the expression of SDC-1 in the kidney and the effect of I/R on SDC-1 expression, we performed an immunohistochemical study of kidneys from sham-operated and I/R mice (n = 6 in each group). We found that SDC-1 was mainly localized in the corticomedullary zone of the kidney and distributed on both the basolateral and luminal sides of renal TECs. By comparing PAS staining, we observed that SDC-1 was primarily expressed in glycogen structures on the luminal side of TECs (Figure 1A). Interestingly, SDC-1–positive staining appeared in the medulla of the kidney after IRI and was considered to represent IRI-induced SDC-1 shed from the corticomedullary zone of the kidney (Figure 1B). Thus, we measured the serum-soluble SDC-1 levels, the indicators of in vivo SDC-1 shedding,36 and found that I/R promoted the elevation of serum soluble SDC-1 level (Figure 1C). In addition, the mRNA expressions of MMP7, MMP9, and ADAM17, which are known sheddases of SDC-1,13–16 were upregulated in I/R challenged kidneys, and the elevation of MMP7 mRNA expression was the most evident, indicating MMP7 is probably a major sheddase of SDC-1 (Figure 1D). Furthermore, we measured the protein expression of MMP7 using Western blotting (Figure 1E) and immunohistochemical staining (Figures 1F and G). The results demonstrated that MMP7 was predominately expressed in the cytoplasm of TECs, and IRI significantly elevated the protein level of MMP7. Additionally, SDC-1 protein expression was increased in I/R-challenged kidneys, likely as a compensation mechanism for SDC-1 shedding (Figure 1E). Overall, we concluded that IRI promoted shedding of SDC-1.

FIGURE 1.

The distribution of SDC-1 in the kidney and shedding of SDC-1 was increased after IRI. A-B, Representative photomicrographs of immunohistochemical staining for SDC-1 of renal sections from sham and I/R-operated mice. A, Syndecan-1-positive immunohistochemical staining was mainly observed in the cortico-medullary zone of the kidney, with little expression in the medulla. Syndecan-1 was localized at both the basolateral and luminal sides of tubular cells. According to PAS staining, SDC-1 was primarily expressed in the glycogen structure on the luminal sides of tubular cells; B, compared with sham-operated kidney, SDC-1–positive immunohistochemical staining appeared in the medulla of the kidney. C, The ELISA results of serum soluble SDC-1 levels in sham and I/R groups. D, The relative mRNA expression levels of MMP7, MMP9, and ADAM17 in kidneys from the 2 groups. The expression levels of MMP7, MMP9, and ADAM17 were all increased, and the elevation of MMP7 mRNA level was the most evident; E, Western blot analysis of SDC-1 and MMP7 in I/R challenged kidneys. F-G, Representative photomicrographs and quantitative analysis of MMP7 immunohistochemical staining of renal sections from mice in the sham and I/R groups. The data are shown as the mean ± SEM, **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; n = 6.

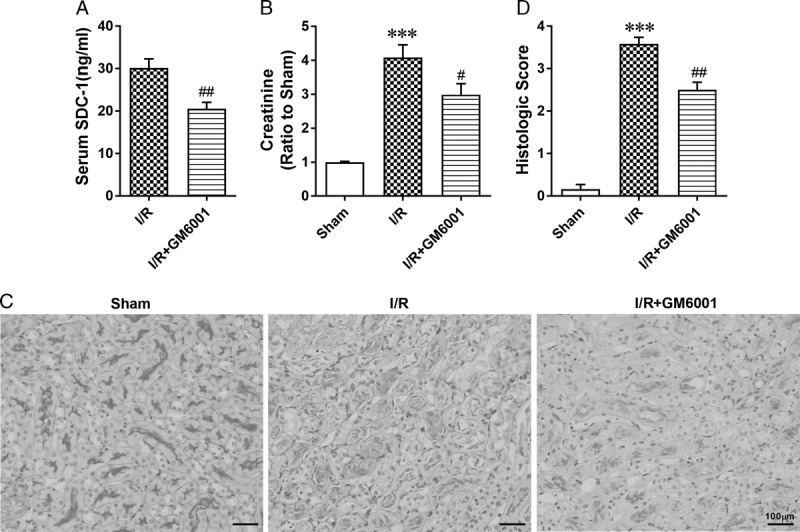

Pretreatment With GM6001 to Suppress SDC-1 Shedding Alleviated I/R-induced Kidney Injury

Because MMPs are known to participate in the proteolysis of SDC-1 ectodomain,17 we used GM6001, a general inhibitor of MMPs, before I/R to inhibit SDC-1 shedding (n = 6 in each group). The ELISA results demonstrated GM6001 pretreatment could attenuate I/R-induced SDC-1 shedding (Figure 2A). Serum creatinine levels were examined, and PAS staining was performed to evaluate the severity of kidney injury. The elevation of serum creatinine levels induced by IRI was significantly reduced with administration of GM6001 (Figure 2B). Moreover, the morphological damage, characterized by loss of the brush border, detachment of tubular cells and luminal cast formation, in GM6001 + I/R mice was evidently milder than that of the I/R group (Figure 2C). Additionally, the histopathologic score of GM6001 + I/R mice showed a significant decrease compared with that of the I/R group (Figure 2D).

FIGURE 2.

Inhibiting SDC-1 shedding by pretreatment with GM6001 protected against IR-induced renal injury. Mice in the GM6001 + I/R group were pretreated with GM6001 (100 mg/kg) 18 hours before I/R surgery. A, The serum soluble SDC-1 levels in I/R and I/R + GM6001 groups determined by ELISA. B, Serum creatinine levels in the 3 groups. C, Representative images of kidney sections stained with PAS in sham, I/R and I/R + GM6001 groups. D, Assessment of morphologic injury quantified with histologic scores in each group. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM; ***P < 0.001 vs sham group; #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01 vs I/R group; n = 6.

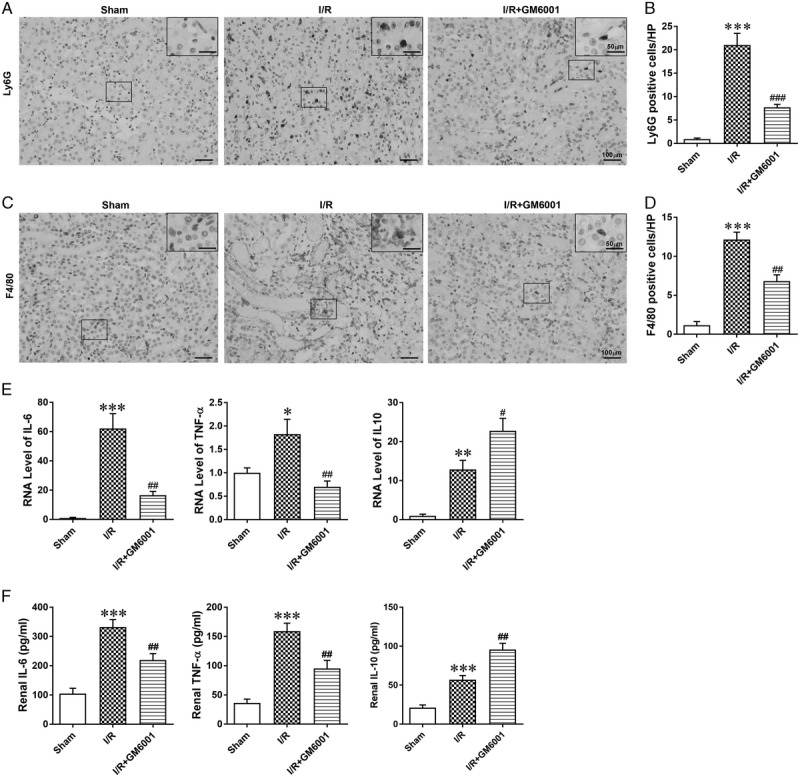

GM6001 Pretreatment Attenuated Renal Inflammation Induced by I/R

Renal dysfunction following IRI is closely related to inflammatory response.2,4 To explore the effect of GM6001 on the I/R-induced inflammatory response, we stained kidney sections with antibodies against LY6G and F4/80, which are neutrophil and macrophage markers, respectively. Pretreatment with GM6001 attenuated the I/R-induced interstitial infiltration of neutrophils (Figures 3A and B, n = 6 in each group) and macrophages (Figures 3C and D). Moreover, we measured the levels of various cytokines in the kidneys. The results revealed that I/R promoted the mRNA levels of the inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNFα and upregulated that of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in the kidneys. Inhibition of SDC-1 shedding reduced the effect of I/R on IL-6 and TNFα mRNA levels but further increased the IL-10 mRNA level after IRI (Figure 3E). ELISA results revealed similar changes in the renal protein levels of these cytokines (Figure 3F).

FIGURE 3.

Pretreatment with GM6001 attenuated I/R-induced inflammatory cell infiltration and cytokine production. A, Representative images of LY6G (marker for neutrophils) immunohistochemical staining in renal sections from sham, I/R and I/R + GM6001 groups. B, Number of Ly6G+ cells in renal sections. C, Representative images of F4/80 (marker for macrophages) immunohistochemical staining in renal sections from sham, I/R and I/R + GM6001 groups. D, Number of F4/80+ cells in renal sections. E, The relative mRNA expression levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-10 in kidneys from the 3 groups. F, Protein concentration of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in kidneys from each group. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 vs sham group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, and ###P < 0.001 vs I/R group; n = 6.

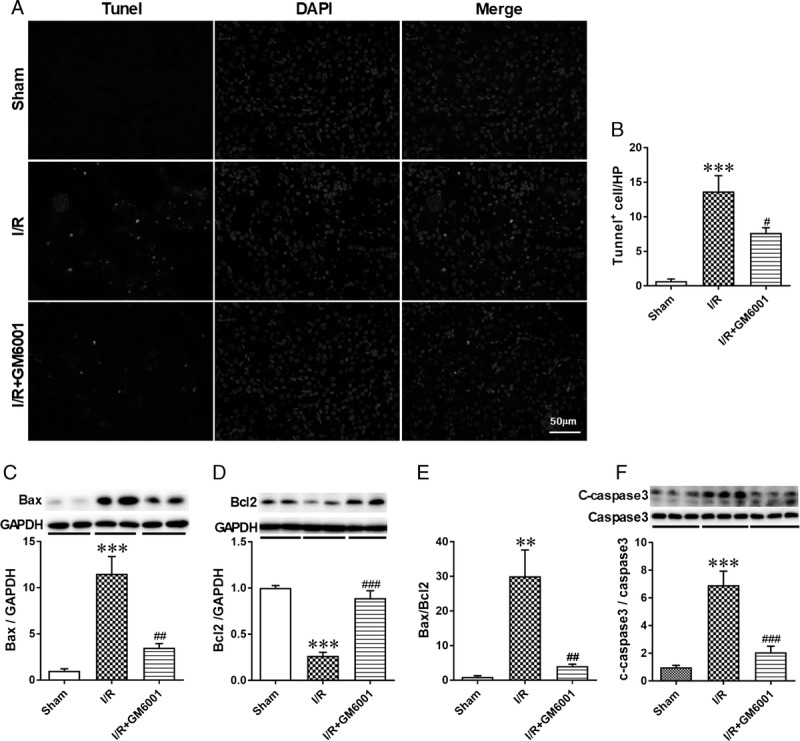

Pretreatment With GM6001 Reduced IR-induced Apoptosis of TECs

Apoptosis of TECs contributes to the pathogenesis of IRI.37 To evaluate the effect of suppressing SDC-1 shedding on tubular apoptosis in I/R-induced AKI, we performed TUNEL staining to analyze apoptotic renal cells. Administration with GM6001 evidently decreased the number of I/R-induced TUNEL-positive cells (Figures 4A and B, n = 6 in each group). The expression ratio of Bax/Bcl2 is a reliable indicator of apoptotic activity.3 We found that I/R mice had higher expression of proapoptotic Bax and lower expression of antiapoptotic Bcl2 than sham mice, resulting in an evident increase in the Bax/Bcl2 expression ratio. Pretreatment with GM6001 attenuated these changes (Figures 4C-E). In addition, we examined the protein level of cleaved caspase-3, which is an essential effector of apoptotic activity.3 Ischemia/reperfusion injury resulted in a significant upregulation of cleaved caspase-3, which was inhibited by GM6001 pretreatment (Figure 4F).

FIGURE 4.

Pretreatment with GM6001 inhibited I/R-induced apoptosis of tubular epithelial cells. A, Representative immunofluorescence images of TUNEL staining of kidneys from mice in the sham, I/R and I/R + GM6001 groups. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue), and green fluorescence represents TUNEL-positive nuclei. B, Quantitative analysis of TUNEL-positive cells in renal sections from the 3 groups. C, Western blot analysis of Bax in samples from sham, I/R and I/R + GM6001 groups. D, Western blot analysis of Bcl2 from these groups; E, Quantitative analysis of the Bax/Bcl2 expression ratio in the 3 groups. F, Representative immunoblots of the cleaved and total caspase-3 expression in these groups and the ratio of cleaved and total caspase-3. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM; **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 vs sham group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, and ###P < 0.001 vs I/R group (n = 6).

GM6001 Inhibited the Shedding of SDC-1 and Apoptosis of HK-2 Cells Induced by H/R

To determine if shedding of SDC-1 on HK-2 cells was accelerated under H/R conditions, we examined the concentration of soluble SDC-1 in HK-2 cell culture medium and observed an evident increase after H/R treatment (Figure 5A). As expected, the MMP7 protein expression was also elevated under H/R condition, indicating the activity of SDC-1 cleavage was upregulated. Similar to the results in vivo, the protein expression of SDC-1 was increased to compensate for the increased shedding of SDC-1 under hypoxia (Figures 5B and C, n = 6 in each group).

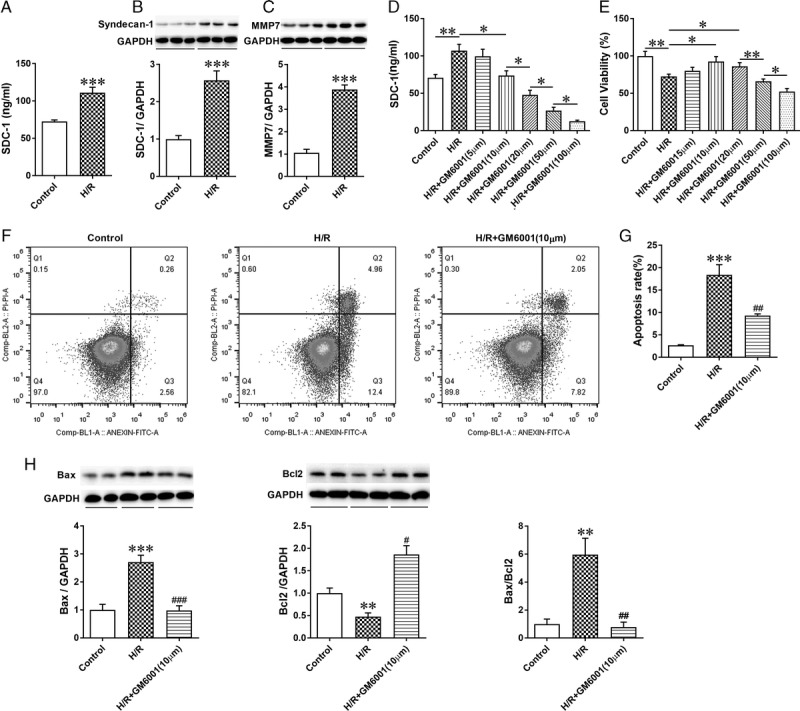

FIGURE 5.

H/R-induced shedding of SDC-1 and inhibition of SDC-1 shedding by GM6001 alleviated apoptosis of HK-2 cells. A, The concentration of soluble SDC-1 in HK-2 cell culture medium determined by ELISA under H/R conditions; B-C, Western blot analysis of sydencan-1 and MMP7 expression in H/R-treated HK-2 cells; D, HK-2 cells in the GM6001 + H/R groups were administered different doses of GM6001 (5 μM, 10 μM, 20 μM, 50 μM, or 100 μM) before H/R treatment. GM6001 inhibited SDC-1 shedding in a dose-dependent manner. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 (n = 6) E, Cell viability measured by CCK8. The cell viability was increased when cells were pretreated with 10 μM GM6001 under hypoxia but decreased with an increase of the GM6001 dose. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 (n = 6). F, Typical images of Annexin-V/PI staining in cells pretreated with GM6001 (10 μM) under hypoxia, evaluated by flow cytometry. G, Quantitative analysis of the apoptosis ratio using FlowJo Version X software. H, Representative immunoblots of Bax and Bcl2 in samples from control, H/R, and H/R + GM6001 (10 μM) groups. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 vs control group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, and ###P < 0.001 vs H/R group; n = 4 for flow cytometry analysis; n = 6 for the other studies.

To confirm the effect of GM6001 on SDC-1 shedding inhibition under H/R conditions, we used a variety of doses of GM6001 (5, 10, 20, 50, and 100 μM) to treat HK-2 cells before H/R treatment (n = 6 in each group). The results demonstrated that SDC-1 shedding was inhibited in a dose-independent manner (Figure 5D). Interestingly, the beneficial effect of GM6001 against H/R injury showed an opposite trend when the dose was increased beyond 10 μM (Figure 5E). Therefore, GM6001 at 10 μM was selected to inhibit shedding of SDC-1 in further studies.

To further investigate the effect of SDC-1 shedding inhibition under H/R conditions, annexin V-FITC/PI staining was used to analyze HK-2 cell apoptosis. Quantitatively, administration with GM6001 (10 μM) to suppress SDC-1 shedding alleviated the percentage of apoptotic HK-2 cells after H/R-treatment (Figures 5F and G, n = 4 in each group). To confirm the antiapoptotic role of GM6001, we examined the expression of the proapoptotic Bax and antiapoptotic Bcl2 proteins. Our findings suggested that H/R increased the expression of proapoptotic Bax and reduced activation of antiapoptotic Bcl2, resulting in an evident upregulation of the Bax/Bcl2 expression ratio, which was reduced by GM6001 pretreatment. (Figure 5H, n = 6 in each group). These results indicated that the reduced cell viability and augmented apoptosis under H/R conditions could be attenuated by suppression of SDC-1 shedding.

Suppression of SDC-1 Shedding Potentiated the c-Met/AKT/GSK-3β Pathway After IRI Both In Vivo and In Vitro

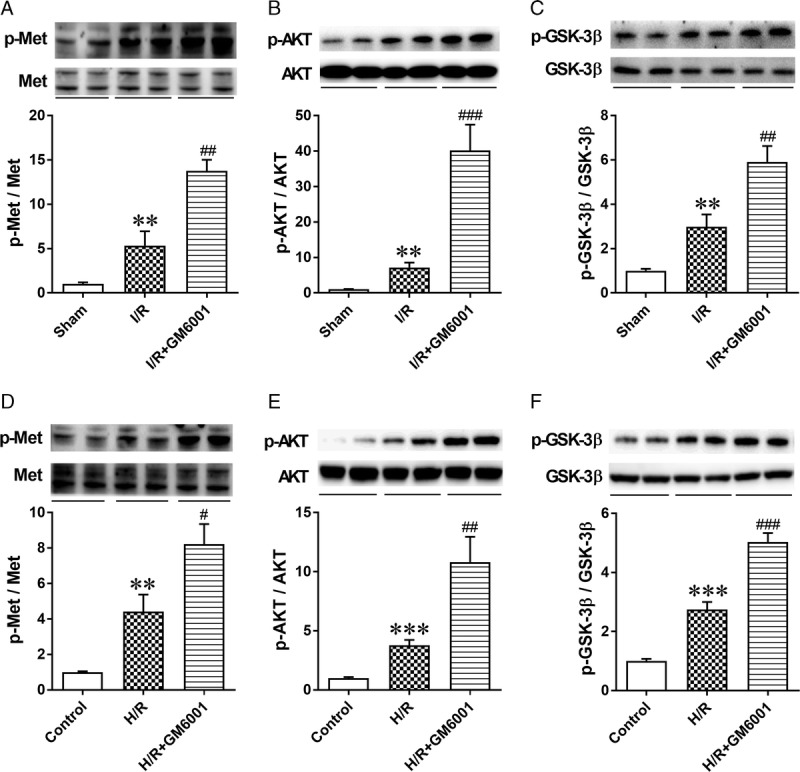

Previous studies have found that HGF-stimulated signaling plays an important role in alleviating acute renal injury.32 Therefore, we investigated whether SDC-1, as the coreceptor of HGF, regulates renal inflammation and epithelial apoptosis by potentiating activation of c-Met and its target effectors, AKT and GSK-3β. As demonstrated in Figure 6 (n = 6 in each group), we found increased phosphorylation of c-Met and its downstream effectors, AKT and GSK-3β, in I/R-challenged kidney and H/R-treated HK-2 cells. The use of GM6001 before I/R surgery (Figures 6A-C) and H/R treatment (Figures 6D-F) further promoted the phosphorylation of c-Met, AKT, and GSK-3β.

FIGURE 6.

Inhibition of syndecan-1 shedding improved activation of the c-Met/AKT/GSK-3β pathway in vivo and in vitro. A-C, Representative immunoblots of the renal protein expression levels of p-Met, c-Met, p-AKT, AKT, p-GSK-3β and GSK-3β, and quantitative analysis of the phosphorylation level of c-Met, AKT, and GSK-3β in sham, I/R and I/R + GM6001 groups. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM; **P < 0.01 vs sham group; ##P < 0.01 and ###P < 0.001 vs IR group; n = 6. D-F, Representative immunoblots of p-Met, c-Met, p-AKT, AKT, p-GSK-3β and GSK-3β and quantitative analysis of the phosphorylation level of c-Met, AKT, and GSK-3β in samples from control, H/R and H/R + GM6001 groups. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM; **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 vs control group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, and ###P < 0.001 vs H/R group; n = 6.

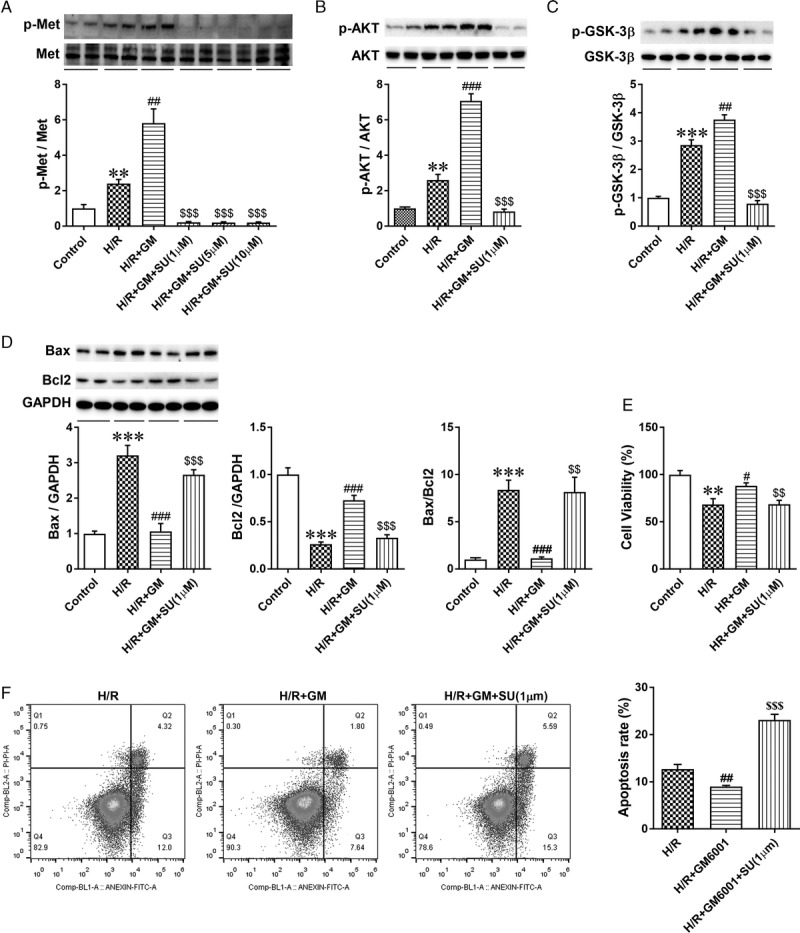

Inhibition of c-Met Phosphorylation Attenuated the Cytoprotective Effect of GM6001 Under Hypoxia

To further examine the mechanism by which GM6001 alleviates apoptosis of HK-2 cells under hypoxia, we used SU11274 (1, 5, and 10 μM), a specific inhibitor of c-Met, to inhibit activation of phospho-Met 18 hours before administration of GM6001 (10 μM) under H/R conditions (n = 6 in each group). We observed that SU11274 at different doses (1, 5, and 10 μM) significantly inhibited the phosphorylation of c-Met similarly (Figure 7A). Therefore, a low dose of SU11274 (1 μM) was used to prevent phosphorylation of c-Met in further studies. The activity of the downstream effectors phospho-AKT and phospho-GSK-3β was also reduced significantly after administration of SU11274 (Figures 7B and C). Moreover, we found that the use of SU11274 suppressed the effect of GM6001 on proapoptotic Bax and antiapoptotic Bcl2 expression under hypoxia (Figure 7D). In addition, administration of SU11274 blunted the reduction in the apoptosis rate of HK-2 cells and the elevation in cell viability after the use of GM6001 under H/R conditions (Figures 7E and F). These results demonstrate that the cytoprotective function of SDC-1 shedding suppression under H/R conditions relies on potentiating the c-Met/AKT/GSK-3β signaling pathway.

FIGURE 7.

Inhibiting phosphorylation of c-Met with SU11274 blunted the protective role of GM6001. A, HK-2 cells were administered SU11274 (1 μM, 5 μM, or 10 μM) 18 hours before the use of GM6001 (10 μM) under H/R conditions. Representative immunoblots and quantitative analysis of p-Met and c-Met levels in these groups. Phosphorylation of c-Met was blocked by treating HK-2 cells with 1, 5, or 10 μM SU11274. B-C, Representative immunoblots of p-AKT, AKT, p-GSK-3β, and GSK-3β expression and statistical analysis of the p-AKT and p-GSK-3β protein levels in samples from control, H/R, H/R + GM6001, and H/R + GM6001 + SU11274 (1 μM) groups. D, Representative immunoblots of Bax and Bcl2 expression and quantitative analysis of Bax and Bcl2 levels and the Bax/Bcl2 expression ratio in control, H/R, H/R + GM6001 and H/R + GM6001 + SU11274 (1 μM) groups. E, Measurement of cell viability using CCK8 in HK-2 cells pretreated with 1 μM SU11274 18 hours before the use of GM6001 under hypoxia. F, Apoptosis of HK-2 cells pretreated with GM6001 (10 μM) and/or SU11274 (1 μM) under hypoxia evaluated by flow cytometry. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM; **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 vs control group; #P < 0.05, ###P < 0.01, and ####P < 0.001 vs H/R group; $$P < 0.01 and $$$P < 0.001 vs H/R + GM6001 group; n = 6.

DISCUSSION

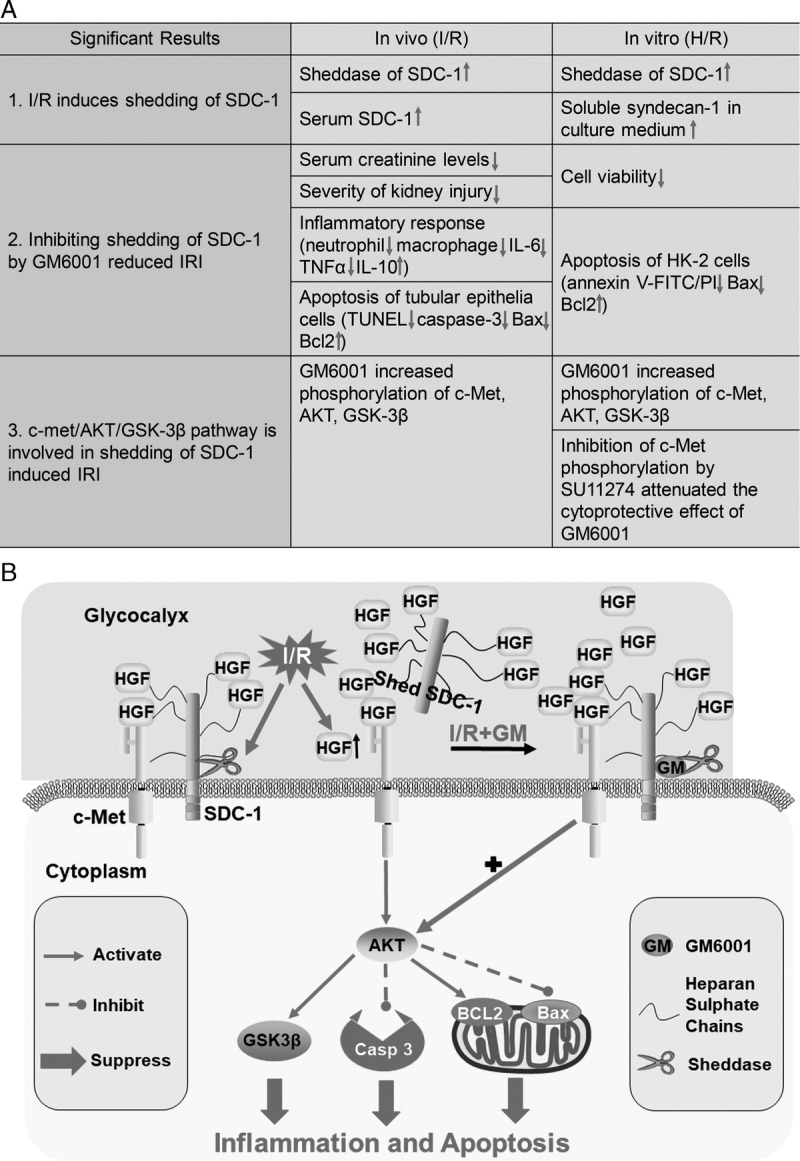

Ischemia/reperfusion injury–induced AKI is a common clinical disease, and there is an urgent need to determine its pathophysiology and an effective therapy regimen.6 Our results indicated that shedding of SDC-1 plays an important role in renal IRI. I/R induced shedding of SDC-1, and inhibiting shedding of SDC-1 had a renoprotective function both in vivo and in vitro by reducing inflammation and apoptosis. The protective effect of SDC-1, which functions as a coreceptor for HGF, is likely mediated by potentiating the c-Met/AKT/GSK-3β signaling pathway. (Figures 8A and B).

FIGURE 8.

Mechanism of the renoprotective function of SDC-1 shedding inhibition in I/R-induced kidney injury. A. the main significant results in this study; B, the diagram depicting the pathways involved in SDC-1. As the coreceptor of HGF, SDC-1 facilitates activation of c-Met and its downstream signal transduction. ischemia/reperfusion improves the activity of SDC-1 shedding mediated by MMPs. However, as a self-protection mechanism of tubular epithelial cells, the production of HGF was upregulated evidently at the same time, resulting in the activation of the downstream pathway AKT/GSK-3β in I/R challenged kidneys. GM6001 pretreatment suppresses shedding of SDC-1, resulting in a more evident increase in the phosphorylation of c-Met/AKT/GSK-3β, an elevation in Bcl2 expression, a reduction in Bax and cleaved caspase-3 activation, and downregulation of inflammatory cytokine production, consequently inhibiting apoptosis and inflammation.

In our study, we observed that SDC-1 was predominately expressed in the corticomedullary junction of the kidney, which is the most susceptible zone to I/R injury. Consistent with previous findings,16,23 we found distribution of SDC-1 on the basolateral side of renal TECs. In addition, we observed that it was also located in the luminal side of TECs, similar to the distribution of glycogen shown by PAS staining, indicating that SDC-1 was also expressed in glycogen structures on the luminal side of TECs. Recent studies have alleged that SDC-1 is a major constituent of the endothelial glycocalyx.38,39 Though we did not find direct evidence in this research, it is worth further investigation because of the important protective role of the endothelial glycocalyx layer in IRI.

The proteolysis of SDC-1 ectodomain is known to regulated by MMP713,14 and additional proteases, like MMP915 and ADAM17.16 As expected, the mRNA levels of MMP7, MMP9, and ADAM17 were upregulated after IRI in our study. The ELISA results demonstrated GM6001, a general inhibitor of MMPs, could prevent SDC-1 shedding both in vivo and vitro. So we used GM6001 in the further study to investigate the effect of inhibiting SDC-1 shedding on I/R challenged kidney. Additionally, we observed that the rise of MMP7 mRNA levels induced by I/R injury were the most evident, indicating MMP7 is probably a major sheddase of sydencan-1. Using knockout cells for MMP7 or MMP7−/− mice would help to clarify the specificity of MMP7 on regulating SDC-1 shedding. Moreover, consistent with the findings of Celie et al,23 we found the expression of SDC-1 was also upregulated after I/R and H/R treatments, which we conferred to be a compensatory reaction to the increased shedding of SDC-1.

Inflammatory responses and apoptosis are vital pathogenic factors that contribute to the renal damage in ischemic AKI.2,3,40 Our study revealed that suppression of SDC-1 shedding contributed to alleviating the inflammation in IR-induced AKI, which was in line with studies in other disease models.41–43 In fact, shedding of the SDC-1 complex and cytokines can direct inflammatory cell influx to locations of injury.13,44 In addition, our results demonstrated that the upregulated apoptotic activity of TECs induced by IRI was suppressed and renal function was improved after inhibition of SDC-1 shedding by GM6001 pretreatment, which were consistent with findings in SDC-1–deficient mice.16

Although the protective role of GM6001 inhibiting syndecan-1 shedding against renal inflammation and apoptosis of TECs is evident in vivo, we found an interesting phenomenon in vitro study: the beneficial effect of GM6001 against H/R injury showed the opposite trend with further increases in dose when the dose reached 10 μM. We speculate that overinhibition of MMPs and drug toxicity at higher doses may explain the phenomenon. Although most of the MMPs effects on substrates are proapoptotic, MMPs have dual antiapoptotic roles against I/R injury, including inactivating proapoptotic proteases, such as calpain 2,45 and releasing growth factors from matrix hidden compartments, such as stem cell factor (SCF).46 Thus, overinhibition of MMPs with high-dose GM6001 may result in decreased cell viability. In addition, increased drug toxicity with an increase in GM6001 dose is also a considerable factor.

Hepatocyte growth factor and its specific receptor, c-Met, play pivotal roles in attenuating renal dysfunction after AKI.32,47 Previous studies have found an early dramatic elevation in the levels of circulating plasma HGF protein48 and a significant increase in activated c-Met in injured kidneys.49 The downstream effectors of c-Met, AKT, and GSK-3β, are key mediators through which HGF exerts its anti-inflammatory and antiapoptotic actions.50,51 Our results showed that phosphorylation of the c-Met/AKT/GSK-3β signaling pathway was activated during I/R and H/R and was further upregulated after inhibition of SDC-1 shedding. This explains the important role of SDC-1 as a coreceptor for HGF to attenuate apoptosis and inflammation in IRI. Brauer et al28 found a similar phenomenon in lung injury induced by influenza infection using SDC-1−/− mice. Furthermore, our data showed that inhibition of c-Met phosphorylation attenuated the cytoprotective effect of suppressing SDC-1 shedding, which suggested that the antiapoptotic function of SDC-1 is likely mediated by the c-Met/AKT/GSK-3β pathway.

Apart from preventing SDC-1 shedding to facilitate HGF binding to c-Met, the use of GM6001 may also upregulate the phosphorylated c-Met level by inhibiting MMP activity to reduce ectodomain shedding of c-Met. Duarte et al52 demonstrated that deficiency of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1, an endogenous inhibitor of MMPs, increased proteolytic ectodomain shedding of c-Met, and Schelter et al53 found that A Disintegrin And Metalloproteinase-10 (ADAM-10) mediated DN30-induced Met shedding. Moreover, the shed c-Met ectodomain can act as a competitive receptor to interfere with HGF binding to c-Met. Further research on the mechanisms of GM6001 upregulating c-Met signaling pathway is worthy of studying.

There are some limitations in our research. As a general inhibitor of MMPs, the effect of GM6001 is not confined to inhibit SDC-1 shedding after I/R insult. Finding a more specific way to suppress SDC-1 shedding, such as exploring the effect of knockout cells for MMP7 or other proteases on SDC-1 shedding, is worth studying. Studies on SDC-1−/− mice to elucidate the important role of SDC-1 in IRI are also of interest. In addition, because shedding of SDC-1 evidently increased after IRI, as we observed in our study, the serum and urine concentration of SDC-1 is likely a potential indicator of AKI. Previous studies have shown the clinical value of SDC-1 in predicting renal function after pediatric cardiac surgery and acute decompensated heart failure.24,26 The predictive value of SDC-1 in the occurrence and outcome of AKI deserves further study.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, our findings suggested that I/R promoted SDC-1 shedding mediated by MMP7 and other proteases. Inhibiting SDC-1 shedding with GM6001 played renoprotective roles against IRI by activating c-Met/AKT/GSK-3β pathway. Further experimental and clinical studies on SDC-1 shedding would be valuable in preventing and treating AKI.

Footnotes

Z.L. and N.S. are co-first authors, these authors contributed equally to this work.

This work was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81500048, 81430015, and 81670614), Talent Development Program of Zhongshan Hospital-Outstanding Backbone Project (2017ZSGG19) and Shanghai Key Laboratory of Kidney and Blood Purification, Shanghai Science and Technology Commission (14DZ2260200).

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Z.L. and N.S. conceived the study, performed the experiment, generated figures and wrote the article. B.S., X.X., J.H., and Y.N. performed the experiment and collected data. Y.F., Y.S., and Y.D. searched the literature and analyzed the data. X.D. revised the article. J.Z. and T.J. designed the study, interpreted the data, and revised the article.

Correspondence: Jianzhou Zou, Division of Nephrology, Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, PR China. (zou.jianzhou@zs-hospital.sh.cn; Jie Teng, PhD, Division of Nephrology, Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, PR China.teng.jie@zs-hospital.sh.cn).

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives License 4.0 (CCBY-NC-ND), where it is permissible to download and share the work provided it is properly cited. The work cannot be changed in any way or used commercially without permission from the journal.

The authors investigate the role of syndecan-1 in a mouse kidney ischemia reperfusion (I/R) injury model. It is demonstrated that inhibiting I/R-induced syndecan-1 shedding may protect against ischemic acute kidney injury by potentiating the c-Met/AKT/GSK-3β pathway.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lameire NH, Bagga A, Cruz D. Acute kidney injury: an increasing global concern Lancet 2013. 382170–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonventre JV, Yang L. Cellular pathophysiology of ischemic acute kidney injury J Clin Invest 2011. 1214210–4221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Havasi A, Borkan SC. Apoptosis and acute kidney injury Kidney Int 2011. 8029–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jang HR, Rabb H. Immune cells in experimental acute kidney injury Nat Rev Nephrol 2015. 1188–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elshiekh M, Kadkhodaee M, Seifi B. Ameliorative effect of recombinant human erythropoietin and ischemic preconditioning on renal ischemia reperfusion injury in rats. Nephro-Urology Monthly. 2015;7:e31152. doi: 10.5812/numonthly.31152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellomo R, Kellum JA, Ronco C. Acute kidney injury Lancet (London, England 2012. 380756–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Couchman JR. Syndecans: proteoglycan regulators of cell-surface microdomains? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2003. 4926–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xian X, Gopal S, Couchman JR. Syndecans as receptors and organizers of the extracellular matrix Cell Tissue Res 2010. 33931–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baston-Buest DM, Altergot-Ahmad O, Pour SJ. Syndecan-1 acts as an important regulator of CXCL1 expression and cellular interaction of human endometrial stromal and trophoblast cells. Mediators Inflamm. 2017;2017:8379256. doi: 10.1155/2017/8379256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lam DC, Chan SC, Mak JC. S-maltoheptaose targets syndecan-bound effectors to reduce smoking-related neutrophilic inflammation. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12945. doi: 10.1038/srep12945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Afratis NA, Nikitovic D, Multhaupt HA. Syndecans—key regulators of cell signaling and biological functions FEBS J 2017. 28427–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Derksen PW, Keehnen RM, Evers LM. Cell surface proteoglycan syndecan-1 mediates hepatocyte growth factor binding and promotes Met signaling in multiple myeloma Blood 2002. 991405–1410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gill SE, Nadler ST, Li Q. Shedding of syndecan-1/CXCL1 complexes by matrix metalloproteinase 7 functions as an epithelial checkpoint of neutrophil activation Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2016. 55243–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X, Zuo D, Chen Y. Shed Syndecan-1 is involved in chemotherapy resistance via the EGFR pathway in colorectal cancer Br J Cancer 2014. 1111965–1976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brule S, Charnaux N, Sutton A. The shedding of syndecan-4 and syndecan-1 from HeLa cells and human primary macrophages is accelerated by SDF-1/CXCL12 and mediated by the matrix metalloproteinase-9 Glycobiology 2006. 16488–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adepu S, Rosman CW, Dam W. Incipient renal transplant dysfunction associates with tubular syndecan-1 expression and shedding Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2015. 309F137–F145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manon-Jensen T, Itoh Y, Couchman JR. Proteoglycans in health and disease: the multiple roles of syndecan shedding FEBS J 2010. 2773876–3889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stepp MA, Pal-Ghosh S, Tadvalkar G. Syndecan-1 and its expanding list of contacts Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle 2015. 4235–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gotte M. Syndecans in inflammation FASEB 2003. 17575–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar AV, Katakam SK, Urbanowitz AK. Heparan sulphate as a regulator of leukocyte recruitment in inflammation Curr Protein Pept Sci 2015. 1677–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang X, Wu C, Song J. Syndecan-1, a cell surface proteoglycan, negatively regulates initial leukocyte recruitment to the brain across the choroid plexus in murine experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis J Immunol 2013. 1914551–4561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szatmari T, Otvos R, Hjerpe A. Syndecan-1 in cancer: implications for cell signaling, differentiation, and prognostication. Dis Markers. 2015;2015:796052. doi: 10.1155/2015/796052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Celie JW, Katta KK, Adepu S. Tubular epithelial syndecan-1 maintains renal function in murine ischemia/reperfusion and human transplantation Kidney Int 2012. 81651–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Melo Bezerra Cavalcante CT, Castelo Branco KM, Pinto Junior VC. Syndecan-1 improves severe acute kidney injury prediction after pediatric cardiac surgery J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2016. 152178–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jing Z, Wei-Jie Y, Yi-Feng ZG. Downregulation of Syndecan-1 induce glomerular endothelial cell dysfunction through modulating internalization of VEGFR-2 Cell Signal 2016. 28826–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neves FM, Meneses GC, Sousa NE. Syndecan-1 in acute decompensated heart failure—association with renal function and mortality Circ J 2015. 791511–1519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rops AL, Gotte M, Baselmans MH. Syndecan-1 deficiency aggravates anti-glomerular basement membrane nephritis Kidney Int 2007. 721204–1215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brauer R, Ge L, Schlesinger SY. Syndecan-1 attenuates lung injury during influenza infection by potentiating c-Met signaling to suppress epithelial apoptosis Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016. 194333–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakamura T, Sakai K, Nakamura T. Hepatocyte growth factor twenty years on: much more than a growth factor J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011. 26188–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oku M, Okumi M, Shimizu A. Hepatocyte growth factor sustains T regulatory cells and prolongs the survival of kidney allografts in major histocompatibility complex-inbred CLAWN-miniature swine Transplantation 2012. 93148–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garajova I, Giovannetti E, Biasco G. c-Met as a target for personalized therapy Transl Oncogenomics 2015. 713–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou D, Tan RJ, Lin L. Activation of hepatocyte growth factor receptor, c-met, in renal tubules is required for renoprotection after acute kidney injury Kidney Int 2013. 84509–520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang C, Hou B, Yu S. HGF alleviates high glucose-induced injury in podocytes by GSK3β inhibition and autophagy restoration Biochim Biophys Acta 2016. 18632690–2699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rampino T, Gregorini M, Camussi G. Hepatocyte growth factor and its receptor Met are induced in crescentic glomerulonephritis Nephrol Dial Transplant 2005. 201066–1074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu X, Kriegel AJ, Liu Y. Delayed ischemic preconditioning contributes to renal protection by upregulation of miR-21 Kidney Int 2012. 821167–1175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seidel C, Ringdén O, Remberger M. Increased levels of syndecan-1 in serum during acute graft-versus-host disease Transplantation 2003. 76423–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Devarajan P. Update on mechanisms of ischemic acute kidney injury J Am Soc Nephrol 2006. 171503–1520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hsia K, Yang MJ, Chen WM. Sphingosine-1-phosphate improves endothelialization with reduction of thrombosis in recellularized human umbilical vein graft by inhibiting syndecan-1 shedding in vitro Acta Biomater 2017. 51341–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kozar RA, Pati S. Syndecan-1 restitution by plasma after hemorrhagic shock J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2015. 78S83–S86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Basile DP, Anderson MD, Sutton TA. Pathophysiology of acute kidney injury Compr Physiol 2012. 21303–1353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen S, He Y, Hu Z. Heparanase mediates intestinal inflammation and injury in a mouse model of sepsis J Histochem Cytochem 2017. 65241–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Y, Wang Z, Liu J. Cell surface-anchored syndecan-1 ameliorates intestinal inflammation and neutrophil transmigration in ulcerative colitis J Cell Mol Med 2017. 2113–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y, Wang Z, Liu J. Suppressing syndecan-1 shedding ameliorates intestinal epithelial inflammation through inhibiting NF-κb pathway and TNF-α. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:6421351. doi: 10.1155/2016/6421351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li Q, Park PW, Wilson CL. Matrilysin shedding of syndecan-1 regulates chemokine mobilization and transepithelial efflux of neutrophils in acute lung injury Cell 2002. 111635–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cauwe B, Opdenakker G. Intracellular substrate cleavage: a novel dimension in the biochemistry, biology and pathology of matrix metalloproteinases Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 2010. 45351–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bengatta S, Arnould C, Letavernier E. MMP9 and SCF protect from apoptosis in acute kidney injury J Am Soc Nephrol 2009. 20787–797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mizuno S, Nakamura T. Prevention of neutrophil extravasation by hepatocyte growth factor leads to attenuations of tubular apoptosis and renal dysfunction in mouse ischemic kidneys Am J Pathol 2005. 1661895–1905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu Y, Tolbert EM, Lin L. Up-regulation of hepatocyte growth factor receptor: an amplification and targeting mechanism for hepatocyte growth factor action in acute renal failure Kidney Int 1999. 55442–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rabkin R, Fervenza F, Tsao T. Hepatocyte growth factor receptor in acute tubular necrosis J Am Soc Nephrol 2001. 12531–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Giannopoulou M, Dai C, Tan X. Hepatocyte growth factor exerts its anti-inflammatory action by disrupting nuclear factor-kappaB signaling Am J Pathol 2008. 17330–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang J, Yang J, Liu Y. Role of Bcl-xL induction in HGF-mediated renal epithelial cell survival after oxidant stress Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2008. 1242–253 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Duarte S, Hamada T, Kuriyama N. TIMP-1 deficiency leads to lethal partial hepatic ischemia and reperfusion injury Hepatology 2012. 561074–1085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schelter F, Kobuch J, Moss ML. A disintegrin and metalloproteinase-10 (ADAM-10) mediates DN30 antibody-induced shedding of the met surface receptor J Biol Chem 2010. 28526335–26340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]