Abstract

Background

We have previously shown that 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) selectively kills myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and activates NLRP3 (NOD-leucine rich repeat and pyrin containing protein 3) inflammasome. NLRP3 activation leads to caspase-1 activation and production of IL-1β, which in turn favors secondary tumor growth. We decided to explore the effects of either a heat shock (HS) or the deficiency in heat shock protein (HSP) 70, previously shown to respectively inhibit or increase NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages.

Methods

Caspase-1 activation was detected in vitro in MSC-2 cells by western blot and in vivo or ex vivo in tumor and/or splenic MDSCs by flow cytometry. The effects of HS, HSP70 deficiency and anakinra (an IL-1 inhibitor) on tumor growth and mice survival were studied in C57BL/6 WT or Hsp70−/− tumor-bearing mice. Finally, Th17 polarization was evaluated by qPCR (Il17a, Rorc) and angiogenic markers by qPCR (Pecam1, Eng) and immunohistochemistry (ERG).

Results

HS inhibits 5-FU-mediated caspase-1 activation in vitro and in vivo without affecting its cytotoxicity on MDSCs. Moreover, it enhances the antitumor effect of 5-FU treatment and favors mice survival. Interestingly, it is associated to a decreased Th17 and angiogenesis markers in tumors. IL-1β injection is able to bypass HS+5-FU antitumor effects. In contrast, in Hsp70−/− MDSCs, 5-FU-mediated caspase-1 activation is increased in vivo and in vitro without effect on 5-FU cytotoxicity. In Hsp70−/− mice, the antitumor effect of 5-FU was impeded, with an increased Th17 and angiogenesis markers in tumors. Finally, the effects of 5-FU on tumor growth can be restored by inhibiting IL-1β, using anakinra.

Conclusion

This study provides evidence on the role of HSP70 in tuning 5-FU antitumor effect and suggests that HS can be used to improve 5-FU anticancer effect.

Keywords: cytokines; immunity, cellular; immunomodulation; inflammation; inflammation mediators

Introduction

Fluorouracil (5-FU) is a chemotherapeutic agent that belongs to the drug class of fluoropyrimidines. To be cytotoxic, 5-FU must be enzymatically converted to a nucleotide by ribosylation and phosphorylation. 5-FU has been used as for 40 years in most of the standard chemotherapeutic protocols for solid cancers, mainly colon, rectum, breast, stomach, liver and pancreas cancers.1 2

However, the use of 5-FU has some limitations, for example, toxicity and time limited effects. In addition to its direct cytotoxic effect, 5-FU can harbor some immunological effects. While this drug is unable to induce immunogenic cell death,3 we have shown that it was able to kill myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), thus promoting antitumor immune response. However, this immune response remains modest since in addition to its capacity to kill MDSCs, this drug can simultaneously entail NOD-leucine rich repeat and pyrin containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome-dependent caspase-1 activation in these cells.3–5 This leads to IL-1β maturation, which in turn favors IL-17 production by CD4+ T cells, angiogenesis and tumor regrowth. The use of an IL-1β pathway inhibitor such as anakinra (a soluble IL-1 receptor that captures both IL-1α and β) is able to enhance 5-FU antitumor efficacy in a murine preclinical model and also in human.4 Presently, in a phase II clinical study we showed that the use of anakinra restored antitumor efficacy of 5-FU in heavily pretreated patients. On the 32 patients enrolled, 5 patients showed a response (CHOI criteria) and 22 patients had stable disease.6 Our study shows an interest in blocking NLRP3/caspase-1/IL-1β pathway in patients treated with 5-FU.

NLRP3 inflammasome is constituted by NLRP3, the adaptor ASC (Apoptosis associated Speck-like protein containing a CARD domain) and pro-caspase-1. On activation, NLRP3 interacts with ASC, which polymerizes into filaments.7 This oligomerized complex can recruit pro-caspase-1, leading to its cleavage and activation. The active caspase-1 will in turn produce mature IL-1β and IL-18.8

NLRP3 inflammasome can be regulated by two ways: by inhibiting the molecular components that drive its activation or by using chemical inhibitors. The main molecular pathways, ions efflux (K+, Ca2+, Cl−), reactive oxygen species (ROS) or oxidized mitochondrial DNA generation, lysosomal destabilization and post-translational modifications of NLRP3 (ubiquitination, phosphorylation) all regulate NLRP3 activation. Several chemical inhibitors were also tested in vivo and in vitro, such as MCC950, CY09, OLT1177, oridonin (targeting NLRP3 ATPase) or tranilast (that targets NLRP3 oligomerization).9 Moreover, we recently showed that heat shock protein (HSP) 70 was a guardian of NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages. In Hsp70−/− macrophages, caspase-1 and IL-1β were overactivated. When HSP70 is overexpressed (eg, by plasmid overexpression or through a heat shock), specific activators were inefficient at inducing NLRP3 inflammasome activation.10 11

We explore here the effect of heat shock or HSP70 deficiency on 5-FU-mediated caspase-1/IL-1β activation in MDSCs and the consequences on tumor growth in a mouse model where the involvement of MDSCs and inflammation has been demonstrated.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

MSC-2 is an immortalized MDSC cell line obtained from BALB/c Gr-1+ splenocytes and was obtained from V. Bronte (Instituto Oncologico, Padova, Italy). EL4 thymoma cells (syngenic from C57BL/6 mice) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. Cells were grown in RPMI 1640 with ultraglutamine (Lonza) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (FBS; Lonza), in an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37°C. In some experiments, a heat shock was performed by incubating MSC-2 cells at 42°C for 1 hour. Cells were then left at 37°C for 2 hours before treatments with 5-FU (Accord). Viability assay was performed using Vybrant MTT Cell proliferation assay kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (ThermoFisher Scientific).

Western blotting

MSC-2 cells were treated in OptiMEM without FBS, supernatants were precipitated and whole-cell lysates were prepared. The supernatants were harvested by centrifugation for 5 min at 400g and precipitated using methanol (500 µL) and chloroform (150 µL). After centrifugation at 12,000g for 10 min, the aqueous phase (at the top) was discarded and 800 µL of methanol was added. Samples were centrifuged at 12,000g for 10 min and the supernatants were removed. Pellets (containing proteins) were dried for 10 min at 37°C, mixed with 40 µL of loading buffer (125 mM Tris–HCl (pH 6.8), 10% β-mercaptoethanol, 4.6% SDS, 20% glycerol and 0.003% bromophenol blue) and incubated at 95°C for 5 min. Whole-cell lysates were prepared by lysing cells in boiling buffer (1% SDS, 1 mM sodium vanadate, 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4)) in the presence of complete protease inhibitor mixture. Samples’ viscosity was reduced by sonication and protein concentration was evaluated. Fifty micrograms of proteins was mixed with loading buffer.

Samples were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and electroblotted to a nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham, GE Healthcare) with a Tris–borate buffer or a Tris–glycin–ethanol buffer (for caspase-1 and IL-1β detection). After incubation for 1 hour at room temperature (RT) with 5% non-fat milk in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)–0.1% Tween-20, membranes were incubated overnight with the primary antibody diluted in PBS–milk–Tween, washed, incubated with the secondary antibody for 30 min or 2 hours (for caspase-1 and IL-1β detection) at RT, and washed again before analysis with a chemiluminescence detection kit (Amersham, GE Healthcare). The following mouse mAbs were used: anti–β-actin (A1978) from Sigma-Aldrich and anti-murine caspase-1 (AG-20B-0044) from Adipogen. We used rat pAb anti-IL-1β (MAB-4011) from R&D Systems. We also used rabbit pAb anti-HSP70 (SPA-812) from Enzo Life Sciences. Secondary Abs HRP-conjugated polyclonal goat anti-mouse and swine anti-rabbit immunoglobulins (Jackson ImmunoResearch) were also used.

Mice

All animals were bred and maintained according to both the FELASA and the Animal Experimental Ethics Committee Guidelines (No. C 21 464 04 EA, University of Burgundy, France). Animals used were between 6 and 22 weeks of age. Female C57BL/6 mice (aged 6 to 8 weeks) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories. C57BL/6 Hsp70−/− mice were obtained from the Mutant Mouse Resource and Research Center, bred and maintained in the Cryopréservation, Distribution, Typage et Archivage Animal (CDTA-Orléans, France).

In vivo experiments

To induce tumor formation, 0.5×106 EL4 cells were injected subcutaneously into mice and 14 days after tumor-cell injection (tumor size, 150–200 mm2) animals were treated.

For hyperthermia experiments, mice were placed on a heating pad at 42°C for 1 hour, then allowed to rest 1 hour. Then, mice received a single intraperitoneal injection of 5-FU (Accord) at 50 mg/kg body weight. For some experiments, 1.5 mg/kg of IL-1Ra (Kineret from Sobi) were injected three times a week, beginning with the chemotherapeutic treatment at day 14. In other experiments, mice received a single intraperitoneal injection of recombinant IL-1β (R&D systems) 2 days after 5-FU treatment. Tumor size was measured three times a week with a caliper. The experiments were performed two or three times and the total number of animals was indicated in the figure legend.

Flow cytometry experiments

Spleens and tumors were recovered 2 days after mice treatments. For spleens, single-cell suspensions were prepared using a 70 µm cell strainer and red cells were removed using hypotonic lysis buffer. For tumors, cells were dissociated using the tumor dissociation kit (130-096-730) with the gentleMACS dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec). One million freshly prepared cells resuspended in RPMI 10% FBS were assessed for caspase-1 activity with the FAM-YVAD-FMK fluorescent probe (FLICA1-ICT098; BioRad) for 1 hour at 37°C as previously described.12 Cells were then stained with a VioBlue anti-mouse Ly6C (130-102-207; Myltenyi Biotec), a BV650 anti-mouse Ly6G (127641) and a BV785 anti-mouse CD11b (101243) (Biolegend) and fixable viability dye (FVD) eFluor780 (Invitrogen) for 15 min at RT. After washing, cells were analyzed with a CytoFlex (Beckman Coulter) and a CytExpert software.

To assess 5-FU effect in vitro, 500,000 splenic cells prepared as above were treated with 1 or 10 µM of 5-FU for 24 hours in RPMI+FBS medium and stained with FAM-YVAD-FMK fluorescent probe for 1 hour at 37°C and then with a VioBlue anti-mouse Ly6C, a BV650 anti-mouse Ly6G and a BV785 anti-mouse CD11b and FVD eFluor780 for 15 min at RT. After washing, cells were analyzed with a CytoFlex (Beckman Coulter) and a CytExpert software.

RT-qPCR

Mice tumors were collected and lysed in Trizol reagent (Applied Biosystems) and total RNA was extracted. Three hundred nanograms of RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using M-MLV reverse transcriptase, random primers and RNAseOUT inhibitor (Applied Biosystems). cDNA was quantified by real-time PCR using Power SYBR Green Real-time PCR kit (Life Technologies) on a QuantStudio 5 detection system (Applied Biosystems). Relative mRNA levels were determined using the ΔΔCt method. Values were expressed relative to Actin b for Eng and Pecam1 or Cd3e levels for Il17a and Rorc. The sequences of the oligonucleotides used are described in online supplementary table 1.

jitc-2019-000478supp001.pdf (7.4MB, pdf)

Immunohistochemistry

Tumors from different treatment conditions (±HS, HSP70−/−) were harvested 48 hours after treatment with 5-FU or PBS as a control. These tumors were placed in tissue storage (Miltenyi, 130-100-008) and then left for a minimum of 48 hours in a formalin bath to fix the tissues. After this step, tumors were included in paraffin and were then cut into 4 µm thick slices. The paraffin was then removed using the PT-link device (Agilent S236784‐2). Slides were labeled for 1 hour with the anti-ERG monoclonal antibody (1/200; Abcam, EPR3864), then stained with ImmPRESS HRP Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (Peroxidase) for 30 min (Vector, MP-7451) to amplify the signal. Finally, slides were stained with DAB (Agilent, SM803 and DM827) and counterstained with hematoxylin (Enzo, ENZ‐ACC106) and were mounted and digitally scanned using the Nanozoomer HT2.0 device (Hamamatsu). Staining quantification was carried out using QuPath software (v.01.3 ref). The appropriate threshold to discriminate positive cells from negative was determined on positive controls (endothelial cells of large vessels). To analyze the whole cohort, we generated two scripts. The first one was dedicated to upload 12 rectangles of 160,000 µm². These areas were then randomly placed on slides by the investigator. The second script detected ERG-positive cells in those areas. Then the percentage of positive cells was calculated.

Statistical analyses

In vitro results are shown as means±SD, in vivo results are shown as means±SEM and comparisons of datasets were performed using GraphPad Prism V.8. The following statistical tests were used: for tumor growth, two-way ANOVA followed by the Sidak post-test for multiple comparisons, flow cytometry experiments, one-way ANOVA test and for survival log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. All p values were two tailed.

Results

HS inhibits caspase-1 activation in MDSCs in vitro and in vivo

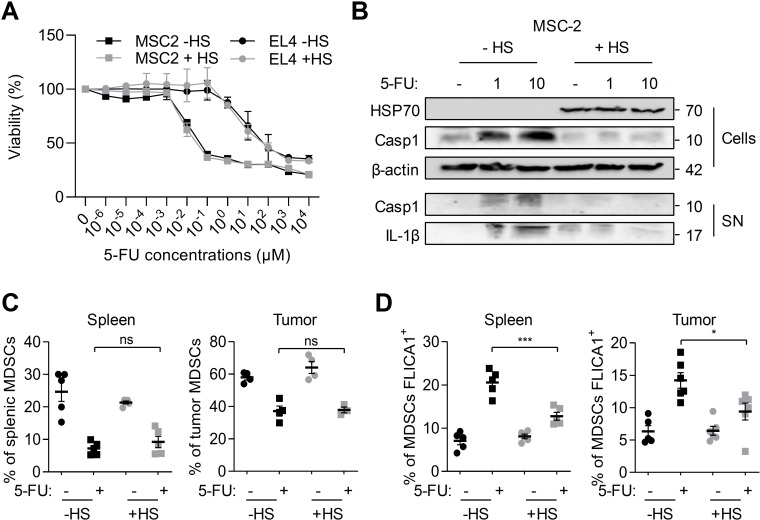

To evaluate the impact of HS on caspase-1 activation in MDSCs, we first performed in vitro experiments on the MSC-2 immortalized MDSC cell line. Cells were treated for 24 hours with indicated concentrations of 5-FU. This treatment decreased cell viability as assessed by MTT assay (figure 1A). When cells were preliminary submitted to a heat shock to allow heat shock protein expression, notably HSP70 (figure 1B), the effects of 5-FU on cell viability were still observed. Similarly, HS did not affect 5-FU-mediated EL4 tumor cells killing (figure 1A). The treatment of MSC-2 cells with 5-FU led to caspase-1 activation and release of active caspase-1 and mature IL-1β in the supernatant (figure 1B). However, a HS leading to HSP70 expression inhibited the activation of caspase-1 and the release of active caspase-1 and mature IL-1β (figure 1B).

Figure 1.

HS inhibits 5-FU-mediated caspase-1 activation in myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) in vitro and in vivo. (A, B) MSC-2 and EL4 cells were submitted or not to a heat shock (HS - 42°C for 1 hour followed by 2 hours at 37°C) and treated or not for 24 hours with indicated concentrations of 5-FU. (A) Cell viability was evaluated by MTT assay. (B) HSP70 and caspase-1 p10 cleavage fragment were detected in cellular extracts (Cells), caspase-1 p10 and IL-1β p17 fragments in the supernatants (SN) by western blot. β-Actin was used as a loading control for cellular extracts. Numbers indicate molecular weights in kDa. (C, D) Spleen and tumor from tumor-bearing C57BL/6 mice heated or not on a pad (42°C, 1 hour) and treated or not with 5-FU (50 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) were harvested after 48 hours, dissociated, stained with FLICA1 and then with CD11b, Ly6C and Ly6G antibodies, FVD and analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) The proportion of MDSCs (Ly6C+ and Ly6G+ in CD11b+, FVD− cells) within spleen or tumor cells was evaluated. (D) The proportion of MDSCs with active caspase-1 (CD11b+, Ly6C+, Ly6G+, FVD−, FLICA1+) was determined. (A) Data represent the mean±SD. (C, D) Data represent the mean±SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.0005, ****p<0.0001, ns, not significant.

To investigate the effects of HS in vivo, we used a 5-FU-treated tumor-bearing mice model.4 Mice were subcutaneously injected with EL4 tumor cells, and when tumors were established, mice were submitted to hyperthermia at 42°C during 1 hour. HS efficiency was checked by evaluating HSP70 overexpression in splenic cells (online supplementary figure 1A). After 48 hours of treatment, the effects of 5-FU on the proportion of splenic and tumor MDSCs and caspase-1 activation in these cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (figure 1C and online supplementary figure 1B). As expected, 5-FU led to a decrease in the proportion of splenic and tumor MDSCs (figure 1C). The total number of MDSCs was also reduced (online supplementary figure 1B). When mice were submitted to a HS before 5-FU treatment, we observed the same effects of 5-FU on MDSC elimination. As previously shown by our team, 5-FU induced caspase-1 activation in splenic and tumor MDSCs. However, HS inhibited 5-FU-mediated caspase-1 activation (figure 1D).

Altogether, our results show that HS is able to inhibit 5-FU-mediated caspase-1 activation without affecting 5-FU MDSC killing.

HS delays tumor growth in 5-FU-treated mice

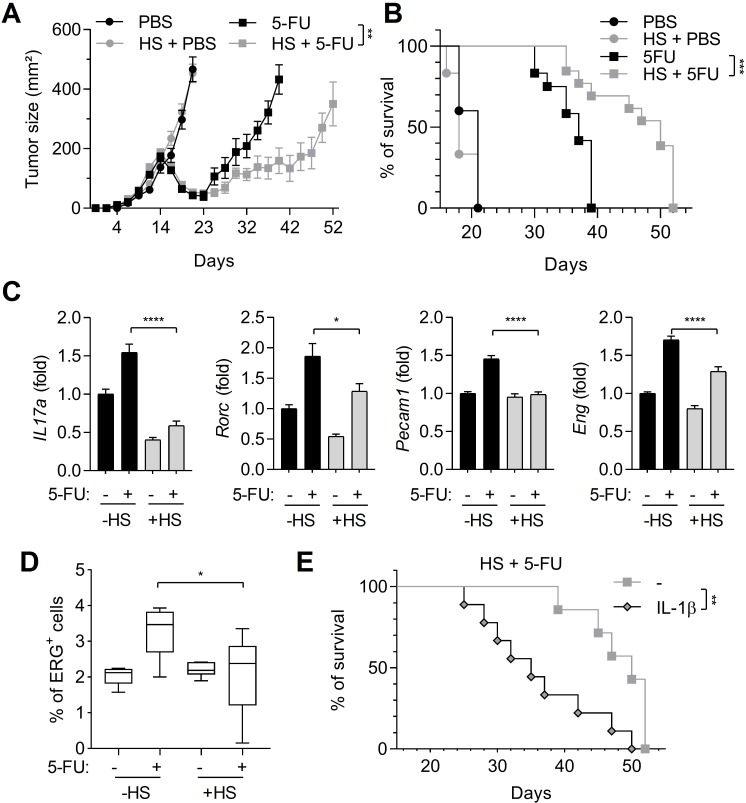

Because HS inhibits caspase-1 activation in MDSCs, we investigated its effects on tumor growth, in mice subcutaneously injected with EL4 tumor cells. As previously described, 5-FU was only able to temporarily decrease tumor growth, but after 23 days, tumors started to grow again (figure 2A). However, when a HS was applied simultaneously with 5-FU treatment, tumor regrowth was more efficiently delayed and mouse survival was increased (figure 2A, B). 5-FU-mediated caspase-1 activation in MDSCs leads to Th17 expansion and neoangiogenesis, both responsible for tumor regrowth.4 Therefore, we evaluated the expression of Th17-related genes (Il17a and Rorc) and angiogenesis-related genes (Eng and Pecam1) within the tumor (figure 2C). In 5-FU-treated mice, these genes were upregulated, whereas in mice submitted to a HS, 5-FU was unable to upregulate these genes. To confirm the results obtained on angiogenesis-related genes, we analyzed the expression of ERG (E-26 Transformation Specific (ETS)-Related Gene), a specific marker of endothelial cells.13 We observed that the capacity of 5-FU to induce the expression of ERG within the tumor, that is, to increase endothelial cell assembly to form microvessels, was decreased when mice were submitted to a HS (figure 2D and online supplementary figure 2). Finally, a single injection of 1 µg of IL-1β was able to accelerate mice death after HS and 5-FU treatments (figure 2E).

Figure 2.

Heat shock (HS) increases 5-FU effects on tumor growth. Tumor-bearing C57BL/6 mice were heated or not on a pad (42°C, 1 hour) and treated or not with 5-FU (50 mg/kg, intraperitoneally). (A, B) Tumor size (n=12 animals per group) was monitored (A) and mice survival was reported (B). (C, D) Tumors were harvested after 48 hours. The expression of indicated genes was analyzed by RT-qPCR (C) and ERG-positive cells’ percentages were evaluated after IHC staining (D). (E) Tumor-bearing C57BL/6 mice heated on a pad (42°C, 1 hour) and treated with 5-FU (50 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) received a single intraperitoneal injection of 1 µg IL-1β and mice survival was evaluated. Data represent the mean±SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.0005, ****p<0.0001, NS, not significant.

To conclude, HS is able to inhibit 5-FU-mediated tumor Th17 expansion and angiogenesis and to delay tumor growth.

HSP70 deficiency increases caspase-1 activation in MDSCs

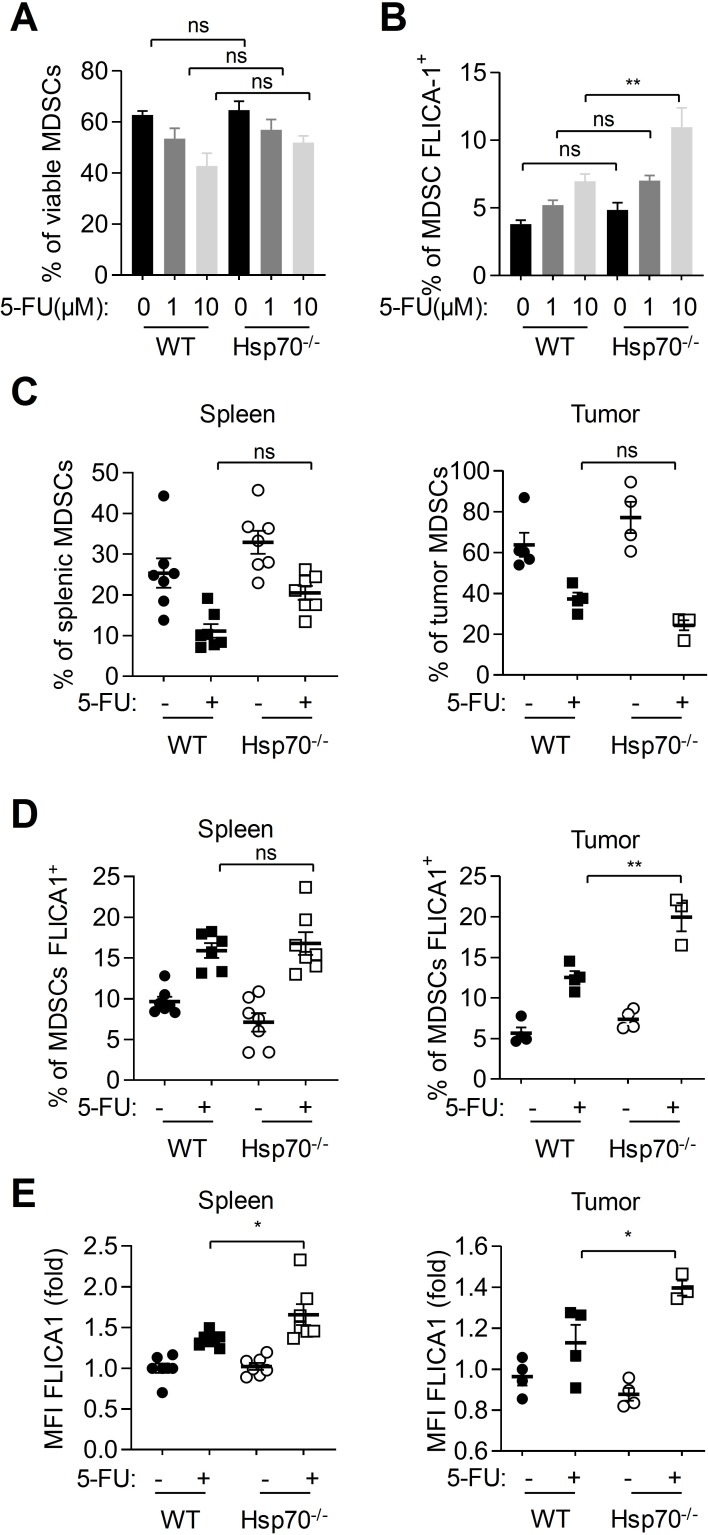

To evaluate the impact of HSP70 deficiency on caspase-1 activation in MDSCs, we performed experiments in splenic cells from wild-type (WT) and Hsp70−/− mice treated in vitro with 5-FU. We observed that 5-FU similarly eliminated MDSCs within WT and Hsp70−/− splenic cells (figure 3A). However, caspase-1 activation was higher in Hsp70−/− than in WT MDSCs after a 10 µM 5-FU treatment (figure 3B). To confirm these observations in vivo, WT and Hsp70−/− mice were subcutaneously injected with EL4 tumor cells. When tumors were established, mice were treated with 5-FU. After 48 hours of treatment, the effects of 5-FU on splenic and tumor MDSCs proportion and caspase-1 activation in these cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (figure 2C-E). We observed that HSP70 deficiency (confirmed by western blot on splenic MDSCs; see online supplementary figure 3A) did not affect the effects of 5-FU on MDSC elimination (figure 2C and online supplementary figure 3B). However, HSP70 deficiency increased caspase-1 activation (figure 2D), it increased the percentage of MDSCs with active caspase-1 in tumors and it emphasized the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) in MDSCs, suggesting a more important caspase-1 activation within each cell.

Figure 3.

HSP70 deficiency increases caspase-1 activation in myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). (A, B) Splenic cells from tumor-bearing mice were treated in vitro with indicated 5-FU concentrations for 24 hours. MDSC viability (CD11b+, Ly6C+, Ly6G+, FVD−) (A) and proportion of MDSCs with active caspase-1 (CD11b+, Ly6C+, Ly6G+, FVD−, FLICA1+) (B) were evaluated by flow cytometry. (C–E) Spleen and tumors from tumor-bearing wild-type (WT) or Hsp70−/− C57BL/6 mice treated or not with 5-FU (50 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) were harvested, dissociated, stained with FLICA1 and then with CD11b, Ly6C and Ly6G antibodies, FVD and analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) The proportion of MDSCs (Ly6C+ and Ly6G+ in CD11b+, FVD−, cells) within spleen or tumor cells was evaluated. (D, E) The proportion of MDSCs with active caspase-1 (CD11b+, Ly6C+, Ly6G+, FVD−, FLICA1+) (D) and the MFI of FLICA1+ MDSCs (E) were determined. Data represent the mean±SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005, ****p<0.001, ns, not significant.

Our results show that HSP70 deficiency is able to increase 5-FU-mediated caspase-1 activation without affecting 5-FU MDSC killing.

HSP70 deficiency in mice accelerates tumor growth after 5-FU treatment in an IL-1β-dependent manner

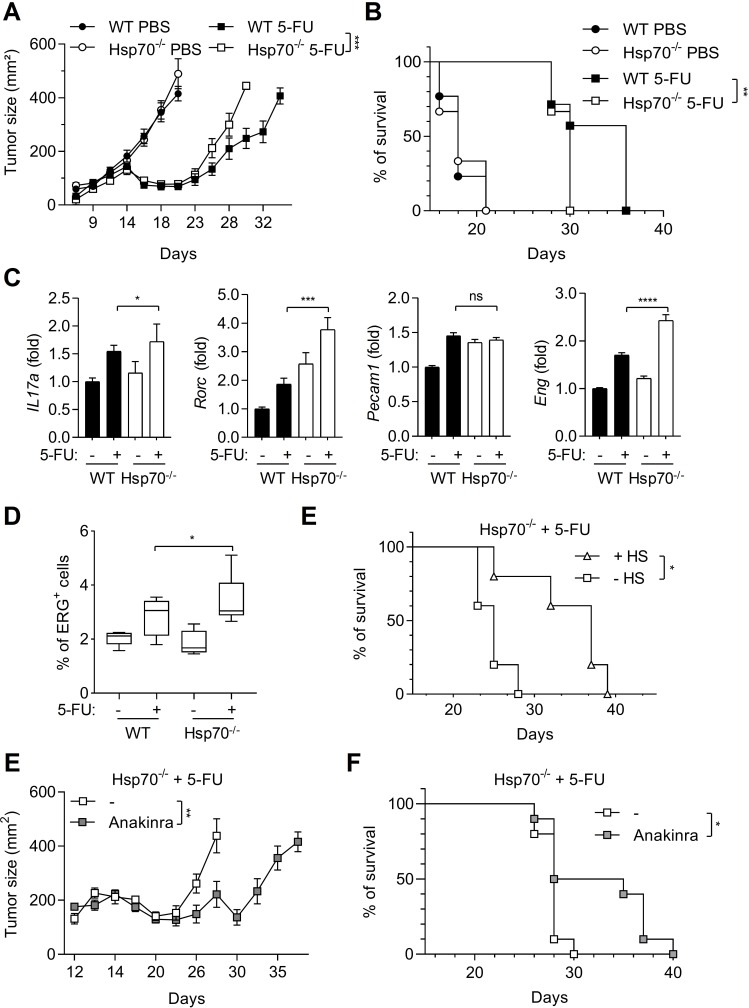

Because HSP70 deficiency increases caspase-1 activation in MDSCs, we investigated its effects on tumor growth. WT and Hsp70−/− mice were subcutaneously injected with EL4 tumor cells and when tumors were established, mice were treated with 5-FU. After 23 days, tumors started to regrow in WT mice (figure 4A). However, in Hsp70−/− mice, tumor regrowth was faster and led to a decrease in mouse survival (figure 4A, B). Again, we evaluated the expression of Th17 cells and angiogenesis-related genes within the tumor (figure 4C). In Hsp70−/− mice, these genes were more importantly upregulated by 5-FU as compared with WT mice. These observations were confirmed by an increased expression of ERG in tumors from Hsp70−/− mice treated with 5-FU (figure 4D). Then, we studied the effect of HS on Hsp70−/− tumor-bearing mice treated with 5-FU. As observed for WT mice, HS was also able to increase Hsp70−/− mice survival, suggesting that the effects of HS in this model not solely relied on HSP70 (figure 4E). To determine whether the effect of HSP70 deficiency on tumor growth relied on the increase in caspase-1 activation in MDSCs and a more important IL-1β production, we inhibited IL-1β using anakinra, a recombinant soluble IL-1Ra. Anakinra was able to delay tumor regrowth and to increase Hsp70−/− mice survival after 5-FU treatment (figure 4E, F).

Figure 4.

HSP70 deficiency limits 5-FU effects on tumor growth in an IL-1β-dependent manner. (A, B) Tumor size was monitored in tumor-bearing wild-type (WT) or Hsp70−/− C57BL/6 mice (n=10 animals per group) treated or not with 5-FU (A) and mice survival was calculated (B). (C, D) Tumors from WT or Hsp70−/− C57BL/6 mice treated or not with 5-FU (50 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) were harvested after 48 hours. The expression of indicated genes was analyzed by RT-qPCR (C) and ERG-positive cells’ percentages were evaluated after IHC staining (D). (E) Tumor-bearing Hsp70−/− C57BL/6 mice survival (n=5 animals per group), submitted or not to a heat shock (HS) and treated with 5-FU (50 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) was evaluated. (F, G) Tumor size was monitored in tumor-bearing Hsp70−/− C57BL/6 mice (n=10 animals per group) treated with 5-FU with or without anakinra injections (1.5 mg/kg, intraperitoneally, 3 days per week) (F) and mice survival was calculated (G). Data represent the mean±SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005, ****p<0.001, ns, not significant.

To conclude, HSP70 deficiency is able to favor Th17 cell expansion and angiogenesis and to improve tumor growth after 5-FU treatment in an IL-1-dependent manner.

Discussion

We show here that HS is able to inhibit caspase-1 activation in MDSCs and tumor growth and conversely that HSP70 deficiency increases caspase-1 activation in MDSCs and accelerates tumor growth in a murine preclinical model.

We have previously shown that 5-FU activates the NLRP3 inflammasome and caspase-1 in MDSCs, leading to IL-1β production. IL-1β was then responsible of IL-17 production by CD4+ T cells, neoangiogenesis and tumor growth.4 Moreover, we showed that inhibiting IL-1β with anakinra had beneficial effects in mice models and in humans. Actually, anakinra is able to cure about half of the tumor-bearing mice treated with 5-FU.4 Moreover, the use of anakinra in a phase II clinical study showed a benefit on patients’ progression-free survival and overall survival.6 However, even if no treatment-related deaths nor serious adverse effects were reported, most patients experienced grade 3 toxicity (neutropenia, digestive side effects and hypertension). These studies highlighted the importance of inhibiting IL-1β in patients treated with 5-FU. Nevertheless, it is necessary to find less toxic alternatives to achieve this goal. In this context, we recently showed that DHA (docosahexaenoic acid) prevented IL-1β production by inhibiting both NLRP3 inflammasome in MDSCs and IL-1β release mechanisms.14 Here, we propose HS as a new non-chemical strategy to inhibit caspase-1 activation within MDSCs. Principles of therapeutic hyperthermia were previously described,15 suggesting that our hyperthermic experiments on mice could be translated in humans. Although the use of hyperthermia on a part of the body can be easily considered, hyperthermia on the whole body is more difficult and hard to implement. The most obvious example in cancer treatment is hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy which is already used for the treatment of colorectal or ovarian peritoneal carcinomatosis.16 17 Moreover, hyperthermia was used for the treatment of some cancers such as local advanced cervical cancers, sarcomas or melanomas, using deep regional apparatus.18–20 Further experiments are required to know the impact of HS and HSP70 on the response of such types of treatments.

We observed that heat shock was also able to increase Hsp70−/− tumor-bearing mice survival after 5-FU treatment. This suggests that in absence of HSP70, hyperthermia may use compensatory pathways such as heat shock factor 1 (HSF-1) or other inducible HSPs.11

We show here that while HS can dampen caspase-1 activation, it has no effect on 5-FU-induced MDSC death. This is in agreement with our previous study that showed that 5-FU-mediated caspase-1 and caspase-3 activation pathways were different.4 This is of great importance, as HS only blocks the deleterious effects of 5-FU.

Moreover, the absence of HSP70 is responsible for an increased caspase-1 activation in MDSCs. The percentage of FLICA1-positive cells was not different between 5-FU-treated WT and Hsp70−/− mice. On the other hand, the MFI of FLICA1 staining is higher in Hsp70−/− MDSCs, illustrating higher levels of caspase-1 cleavage in each cell. This is in agreement with our previous observation on macrophages. In Hsp70−/− macrophages treated with classical NLRP3 inflammasome activators, we observed larger (5–10 µm) and several ASC/NLRP3 specks per cell, whereas WT cells had only one speck of normal size (1–2 µm).10 This can probably explain why caspase-1 activity within 5-FU-treated MDSCs from Hsp70−/− mice was stronger.

Thus, we highlight here the importance of HSP70 expression in patients treated with 5-FU. Accordingly, expression of HSP70 or the presence of a mutation in HSP70 genes in patients could predict the response to 5-FU. In humans, several HSP70 polymorphisms have been reported and were associated to a higher risk of developing inflammatory diseases.21–23 Further work is needed to understand how HSP70 can influence the development of inflammatory diseases that depend on NLRP3 inflammasome dysregulation.24 25

In summary, we demonstrate here that HSP70 is a negative regulator of 5-FU-mediated caspase-1 activation in MDSCs. This work also proposes a new way to inhibit the caspase-1/IL-1β pathway, to improve 5-FU-based chemotherapeutic treatment efficiency, using hyperthermia.

Acknowledgments

We thank Isabel Gregoire for carefully reading the manuscript. We thank the Department of Pathology of the Centre GF Leclerc. We thank the animal housing facility at the University of Burgundy (Dijon, France).

Footnotes

FC and CR contributed equally.

Contributors: TP, FC, AF, CT, AP, VD, AI, LD and MN performed experiments. TP, FC, EL, VD and CR analyzed the data. EJ was responsible for animal providing. FC, EL, VD, CG, FG and CR provided scientific insight. CR designed the study. CR wrote the manuscript. TP, FC, EL, CG and FG corrected the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read and approved the submitted version.

Funding: This work was supported by the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (ARC) and by a French Government grant managed by the French National Research Agency under the program “Investissements d’Avenir” with reference ANR-11-LABX-0021 (Lipstic Labex). FG team is “Equipe labelisée Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer”. FC is a fellow of ARC.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplementary information.

References

- 1.Dean L. Fluorouracil therapy and DPYD genotype : Pratt V, McLeod H, Rubinstein W, et al., Medical genetics summaries. Bethesda (MD), 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asara Y, Marchal JA, Carrasco E, et al. Cadmium modifies the cell cycle and apoptotic profiles of human breast cancer cells treated with 5-fluorouracil. Int J Mol Sci 2013;14:16600–16. 10.3390/ijms140816600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vincent J, Mignot G, Chalmin F, et al. 5-Fluorouracil selectively kills tumor-associated myeloid-derived suppressor cells resulting in enhanced T cell-dependent antitumor immunity. Cancer Res 2010;70:3052–61. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruchard M, Mignot G, Derangère V, et al. Chemotherapy-triggered cathepsin B release in myeloid-derived suppressor cells activates the NLRP3 inflammasome and promotes tumor growth. Nat Med 2013;19:57–64. 10.1038/nm.2999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rébé C, Ghiringhelli F. Cytotoxic effects of chemotherapy on cancer and immune cells: how can it be modulated to generate novel therapeutic strategies? Future Oncol 2015;11:2645–54. 10.2217/fon.15.198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Isambert N, Hervieu A, Rébé C, et al. Fluorouracil and bevacizumab plus anakinra for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer refractory to standard therapies (IRAFU): a single-arm phase 2 study. Oncoimmunology 2018;7:e1474319. 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1474319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu A, Magupalli VG, Ruan J, et al. Unified polymerization mechanism for the assembly of ASC-dependent inflammasomes. Cell 2014;156:1193–206. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Misawa T, Takahama M, Kozaki T, et al. Microtubule-driven spatial arrangement of mitochondria promotes activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Nat Immunol 2013;14:454–60. 10.1038/ni.2550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang Y, Wang H, Kouadir M, et al. Recent advances in the mechanisms of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and its inhibitors. Cell Death Dis 2019;10:128. 10.1038/s41419-019-1413-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martine P, Chevriaux A, Derangère V, et al. Hsp70 is a negative regulator of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell Death Dis 2019;10:256. 10.1038/s41419-019-1491-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martine P, Rébé C. Heat shock proteins and inflammasomes. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20. 10.3390/ijms20184508. [Epub ahead of print: 12 Sep 2019]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Derangère V, Chevriaux A, Courtaut F, et al. Liver X receptor β activation induces pyroptosis of human and murine colon cancer cells. Cell Death Differ 2014;21:1914–24. 10.1038/cdd.2014.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haber MA, Iranmahboob A, Thomas C, et al. ERG is a novel and reliable marker for endothelial cells in central nervous system tumors. Clin Neuropathol 2015;34:117–27. 10.5414/NP300817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dumont A, de Rosny C, Kieu T-L-V, et al. Docosahexaenoic acid inhibits both NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and JNK-mediated mature IL-1β secretion in 5-fluorouracil-treated MDSC: implication in cancer treatment. Cell Death Dis 2019;10:485. 10.1038/s41419-019-1723-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Habash RWY, Krewski D, Bansal R, et al. Principles, applications, risks and benefits of therapeutic hyperthermia. Front Biosci 2011;3:1169–81. 10.2741/e320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lavoué V, Bakrin N, Bolze PA, et al. Saved by the evidence: hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy still has a role to play in ovarian cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 2019;45:1757–9. 10.1016/j.ejso.2019.03.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gelli M, Huguenin JFL, de Baere T, et al. Peritoneal and extraperitoneal relapse after previous curative treatment of peritoneal metastases from colorectal cancer: what survival can we expect? Eur J Cancer 2018;100:94–103. 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pennacchioli E, Fiore M, Gronchi A. Hyperthermia as an adjunctive treatment for soft-tissue sarcoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2009;9:199–210. 10.1586/14737140.9.2.199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Overgaard J, Gonzalez Gonzalez D, Hulshof MC, et al. Hyperthermia as an adjuvant to radiation therapy of recurrent or metastatic malignant melanoma. A multicentre randomized trial by the European Society for Hyperthermic Oncology. Int J Hyperthermia 1996;12:3–20. 10.3109/02656739609023685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franckena M, Fatehi D, de Bruijne M, et al. Hyperthermia dose–effect relationship in 420 patients with cervical cancer treated with combined radiotherapy and hyperthermia. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:1969–78. 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boiocchi C, Osera C, Monti MC, et al. Are Hsp70 protein expression and genetic polymorphism implicated in multiple sclerosis inflammation? J Neuroimmunol 2014;268:84–8. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2014.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klausz G, Molnár T, Nagy F, et al. Polymorphism of the heat-shock protein gene Hsp70-2, but not polymorphisms of the IL-10 and CD14 genes, is associated with the outcome of Crohn's disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 2005;40:1197–204. 10.1080/00365520510023350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pablos JL, Carreira PE, Martín-Villa JM, et al. Polymorphism of the heat-shock protein gene Hsp70-2 in systemic lupus erythematosus. Br J Rheumatol 1995;34:721–3. 10.1093/rheumatology/34.8.721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhong Y, Kinio A, Saleh M. Functions of NOD-like receptors in human diseases. Front Immunol 2013;4:333. 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ozaki E, Campbell M, Doyle SL. Targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome in chronic inflammatory diseases: current perspectives. J Inflamm Res 2015;8:15–27. 10.2147/JIR.S51250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jitc-2019-000478supp001.pdf (7.4MB, pdf)