Abstract

The global COVID-19 pandemic is likely to have a major impact on the experience of death, dying, and bereavement. This study aimed to review and synthesize learning from previous literature focused on the impact on grief and bereavement during other infectious disease outbreaks. We conducted a rapid scoping review according to the principles of the Joanna Briggs Institute and analyzed qualitative data using thematic synthesis. From the 218 identified articles, 6 were included in the analysis. They were four qualitative studies, one observational study, and a systematic review. Studies were conducted in West Africa, Haiti, and Singapore. No research studies have focused on outcomes and support for bereaved people during a pandemic. Studies have tended to focus on survivors who are those who had the illness and recovered, recognizing that some of these individuals will also be bereaved people. Previous pandemics appear to cause multiple losses both directly related to death itself and also in terms of disruption to social norms, rituals, and mourning practices. This affects the ability for an individual to connect with the deceased both before and after the death, potentially increasing the risk of complicated grief. In view of the limited research, specific learning from the current COVID-19 crisis and the impact on the bereaved would be pertinent. Current focus should include innovative ways to promote connection and adapt rituals while maintaining respect. Strong leadership and coordination between different bereavement organisations is essential to providing successful postbereavement support.

Key Words: COVID-19, coronavirus, pandemic, bereavement, grief, mourning, review

Key Message

The multiplicity of loss associated with pandemics impacts upon cultural norms, rituals, and usual social practices related to death and mourning, potentially increasing the risk of complicated grief. Innovative ways to promote connection with people before and after the death and recognition of the need to adapt rituals and mourning practice to honor the dead and provide comfort to survivors are recommended.

Introduction

The global COVID-19 pandemic is likely to have a major impact on the individual and societal experience of death, dying, and bereavement. Owing to social isolating measures and lack of usual support structures, this also is likely to influence experiences of grief and mourning. How palliative care and hospice teams respond to these challenges has been recognized.1

Many factors can influence bereavement including the nature of the death, existing family and social support networks, and cultural context. “Complicated grief” is characterized by intense grief, which can last longer than socially expected or cause impairment in daily functioning.2 Risk factors that can contribute to “complicated grief” include, but are not exclusive to, the following: 1) nature of death, for example, sudden, traumatic, or violent, resulting in a lack of preparedness or limiting the opportunity to “say goodbye”2; 2) nature of the environment, for example, limited end-of-life care discussions, “aggressive” medical care, concurrent caring demands, or other stressors such as financial costs3 , 4; and 3) preexisting factors in the bereaved person, for example, low levels of social support and mental health concerns.2

Internationally, there is variability in the allocation of bereavement support services. Within certain health-care systems, a “blanket” approach to bereavement support is offered by palliative care, but this means the same level of support is offered to everyone, regardless of need and without identification of those at most risk of complicated grief.5

Specific factors associated with COVID-19–related deaths could potentially increase the risk of an adverse outcome in bereavement, such as a more intense or prolonged grief reaction. These factors include the rapidity or unexpected nature of the death. In addition, the isolation and the physical barriers may prevent sensitive and timely communication and limit opportunities to “say goodbye.” Learning from recent infectious disease outbreaks and the subsequent impact on grief and bereavement may guide current care to support families before the death, as well as inform service developments for the provision of ongoing postbereavement support after deaths from COVID-19.

Research Questions

-

1.

What can we learn from previous pandemics/infectious disease outbreaks about the subsequent impact these types of death had on bereavement?

-

2.

Are there specific components of care or support that subsequently influence outcomes during bereavement?

Methods

A rapid scoping review of the literature, in keeping with the principles of the Joanna Briggs Institute, was undertaken.6 An analysis of qualitative data was conducted using thematic synthesis.7

Using specified inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1 ), we searched five databases (MEDLINE [1966-2020], CINAHL [1982-2020], EMBASE [1974-2020], Psychoinfo [1806-2020], and TRIP [2000-2020]). The search strategy (Table 2 ) compromised of key terms for 1) bereavement, grief, and mourning; and 2) pandemics and epidemics including specific named pandemics.

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

|

|

Table 2.

Search Terms Used for Rapid Scoping Review in Medline

|

|

In addition, we searched and screened the reference lists for any included articles. Two researchers (C. R. M., A. J. E. H.) completed all the searches. Articles were screened initially by title and abstract (C. R. M., A. J. E. H.), and full texts were independently screened (C. R. M., A. J. E. H.).

Data were extracted using a specially designed proforma on the aim, setting, country, participants' characteristics, study design, and findings. Verbatim findings from the qualitative studies were extracted with a specific focus on data relevant to bereavement, grief, or mourning. Two researchers (C. R. M. and A. J. E. H.) independently coded text line by line, including relevant participant quotes, according to its meaning and content. The two reviewers then discussed similarities and differences between the codes to start grouping them into descriptive themes.7 Our research questions, additional synthesis, reflection, and discussion (C. R. M., A. J. E. H., S. P., N. P.) generated analytical themes from the studies’ data.

Results

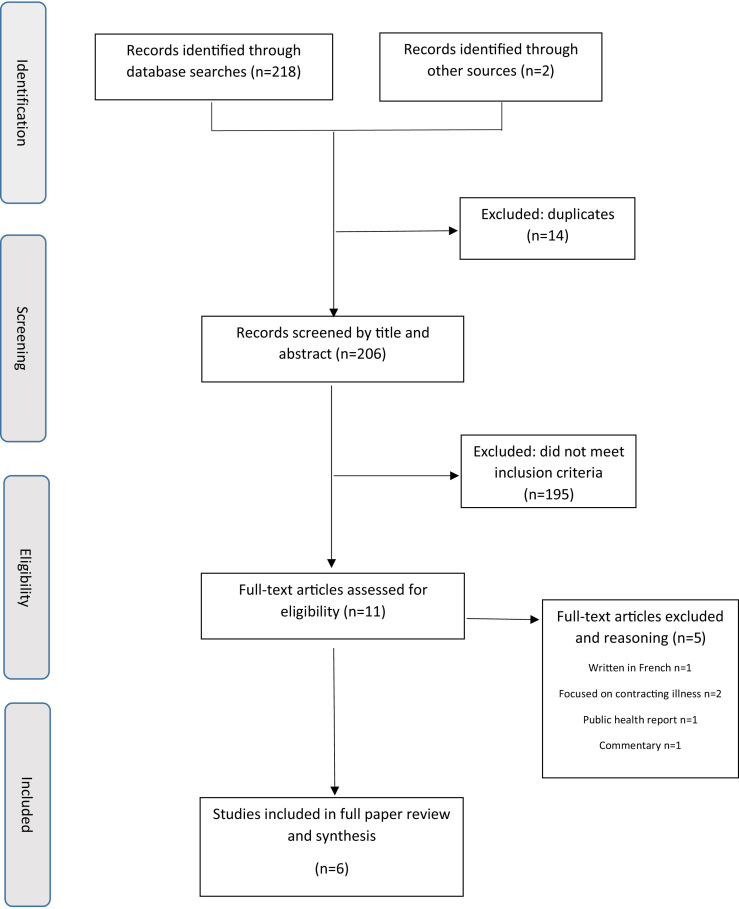

We identified 218 articles from searches conducted on April 7, 2020. Additional two articles were identified from the reference list of a systematic review. After removal of duplicates (n = 14), 195 were excluded after reviewing title and abstract. From the remaining 11 articles, five were excluded after full-text review, and six were included in the analysis (Figure 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Results of rapid literature review.

There were four qualitative studies,8, 9, 10, 11 one observational study,12 and one systematic review.13 Within the qualitative studies, one study focused on palliative health-care professionals (HCPs) involved in the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic in Singapore,8 two studies focused on West African Ebola “survivors,”10 , 11 and one study focused on Haitian community members during the cholera outbreak.9 The observational study was based on patients attending mental health support services in Sierra Leone after the Ebola outbreak,12 and the systematic review was focused on Ebola survivors.13

There was no study that specifically focused on bereaved people and the impact that a death linked to a pandemic had on their subsequent grief. Studies tended to focus on “survivors” of the illness, that is, those who had had the illness and recovered and their subsequent psychological well-being. It was recognized, however, that these survivors could also be bereaved people and indeed some of them may have experienced multiple bereavements.13 For example, one study reported 13 of 143 (9%) people attending a nurse-led mental health outpatient clinic were relatives of the deceased or survivors.12 The article described that both groups presented with normal grief or mild depressive or anxiety symptoms. They also reported on the stigma and discrimination these individuals had faced within their communities.12

Themes

The overarching theme was the “multiplicity of loss” with three identified subthemes, namely “uncertainty”, “disruption of connectiveness and autonomy”, and “factors influencing bereavement outcomes”. Themes are discussed with supporting quotations in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Multiplicity of Loss, Subthemes, and Exemplar Excerpts From Selected Articles

| Subtheme | Description | Exemplar Excerpts From Selected Articles |

|---|---|---|

| Uncertainty | Prognosis: not knowing whether individuals and families needed to prepare for death | “For SARS, death can hit suddenly. Families usually do not have the chance to hear the last words of patients or say their last words to patients.”8 |

| Information: uncertainty surrounding beliefs about the illness, including information provided by relevant authorities |

“It is a poison brought by foreigners to divide us”9 “It is a disease brought by nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) in order to get more money”9 |

|

| Disruption of connectiveness and autonomy | Multiple disruptions having an impact on the ability to “connect” and limiting choices | Physical barriers “ … because you just see people, through this mesh, or they have some kind of eye glass on their face, you only see a small part of a body”11 “They could not be near their loved ones, (or) touch them, (or) whisper to them. Everything had to be done through the cold glass panel.”8 |

| Psychosocial barriers “Family members … had to take care of children or elderly in their homes, or they were too afraid to come into the ETU, or they did not have money for transportation.”10 “I saw him walk out and sit in the common area and cry quietly to himself. Nobody was there to be with him.”8 “The subsequent isolation undermined their healing process and affected their ability to cope, as they received little support during their mourning and could not share their traumatic experiences.”10 | ||

| Loss of autonomy “The patient has no choice over where he dies or over who will be present when he dies.”8 “Going home to die was not possible for the majority of patients due to the difficulties in the discharge process.”8 | ||

| Interruption to usual rituals and practices “ … the rituals and funerals are either absent or shortened (when the body is abandoned or taken away rapidly to be buried in mass graves).”9 “In the Haitian culture and belief system, respect for the dead and ancestors are of tremendous importance, with consequences to individual and collective wellbeing.”9 | ||

| Loss of memorialization “When corpses were cremated, without funerals or formal burial, they did not even have a grave to visit.”10 “the usual processes for grieving become difficult … as there were no graves to visit or corpses were buried in unmarked graves or cremated without formal burial ceremony.”13 | ||

| Factors influencing bereavement outcomes | Opportunities to promote social connections | “Designated meeting rooms with transparent dividers may allow visits of relatives inside the ETU.”10 |

| Respect for rituals in keeping with faith or culture |

“The mourning tent placed inside the CTC allows family members to gather and say a last goodbye to their beloved ones.”9 “The possibility is also offered to the family to contact a religious leader of their choice, should they want a prayer or ritual to be organised before the body is transported and buried.”9 |

|

| Psychosocial support interventions |

‘… psychosocial support interventions can play an important role in the response to such an epidemic.”9 “Support of family, friends, faith, and participation in a survivor's association were frequently mentioned coping strategies ….”10 |

ETU = Ebola Treatment Unit; CTC = Cholera Treatment Center.

Multiplicity of Loss

The overarching theme referred to the experience of loss at many different levels. This not only included the death of family members and witnessing other individuals dying but also represented the symbolic loss of an individuals’ way of life, culture, and usual social practices. The mode of transmission of these types of illnesses challenged cultural norms, for example, desire to provide compassionate care for their family and showing respect and reverence for the deceased.9 , 11

Uncertainty

Uncertainty surrounded two main areas—the prognosis of the disease and beliefs and perceptions about the illness. In the context of SARS, uncertainty reported that the nature of the illness could affect whether or not families were prepared for death and had the opportunity to “say goodbye”.8 In addition, uncertainty surrounded perceptions and beliefs about the illness, including information provided by relevant authorities, for example, governments and charitable organisations.9 Areas of uncertainty could lead to fear among patients, family carers, and HCP,8 which occurred on both an “individual and collective” level.9 Unaddressed fear could manifest as insecurity, psychological distress, drive stigmatization, and sometimes violent reactions toward individuals and institutions.8 , 9

Disruption of Connectiveness and Autonomy

Multifaceted disruptions affected the ability to connect, between patients, family carers, and HCPs, as well as restricting choice. Physical barriers and isolation were created by the need for HCP and family to wear personal protective equipment and the limitation in visiting and physical contact.8 , 11 Usual social support mechanisms were lost because of the inability of family members to visit the patient.10 In addition, family members were unable to directly support each other through their grief.8

Owing to choices being limited, for example, decisions about preferred place of death, autonomy could be compromised.8 In addition, interruption to the usual rituals and practices observed after death was described.9 , 10 These disruptions could impact the subsequent bereavement because of the absence of a memorial or tangible place to subsequently visit.13

Factors Influencing Bereavement Outcomes

There was recognized uncertainty about the long-term impact of these experiences on the bereaved.9 The identified studies reported on a number of factors that could potentially have a positive impact on the subsequent grief. These include opportunities to promote social connections and facilitate communication with family members, for example, designated meeting rooms with transparent dividers.10 Wherever possible, respecting rituals in keeping with faith or culture, for example, allowing support from a religious leader.9 In the Haiti cholera outbreak, a mourning tent was placed outside the treatment center to allow family to say a final goodbye.10 Psychosocial support interventions should be provided both via formal mental health services12 and community initiatives.9 , 10

Discussion

Main Findings

Although no previous study has focused solely on bereaved people, previous pandemics appear to cause multiple losses both directly related to death itself and also in terms of disruption to social norms, rituals, and mourning practices. The disruption affecting an individuals’ ability to connect with the deceased both before and after the death may potentially impact on grief. In particular, the usual societal and cultural rituals can seem rushed, altered, or absent.

In view of the limited research in this area, specific learning from the current COVID-19 crisis and the impact on the bereaved would be pertinent.

What This Study Adds

The multiplicity of loss compounds is already a challenging situation and links with bereavement theories regarding the impact of previous multiple losses.2 In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the uncertainty surrounding the illness and the loss of the usual rituals could lead to distress from unanswered questions or a struggle to accept the death.

Our review confirms the increased prevalence of risk factors associated with complicated grief, for example, sudden/unexpected death and low social support.2 Responses to loss can vary—important influences include the ability to find meaning and make sense of the loss within an individuals’ existing worldview.14 Other humanitarian emergencies relating to war and atrocity also show variable psychological responses influenced by the personal, subjective meaning of events.15

Strategies that could reduce the risk of complicated grief include 1) promote “connection” and communication between the patient, family carer, and HCPs whenever possible, using novel technology to aid communication;1 2) ensure individualized care is practiced in decision-making, advance care planning, and supporting beliefs and wishes; and 3) discuss opportunities for future memoralization.

Although we cannot be certain of the subsequent impact on bereavement, preparation is needed to help develop and provide the most appropriate form of postbereavement support. In the UK organ retention crisis, access to timely and instructive information in the postbereavement period was key; however, staff were not always trained and prepared for this.16 Strong leadership and partnerships between different organisations are essential to establishing successful postbereavement support.12

Limitations

As well as there being few studies, most came from countries with strong cultural and spiritual belief systems that may differ from Western societies. The impact of misperceptions, however, and the doubts about the authenticity of information from relevant authorities have widespread application and are relevant for our current crisis.

A formal quality appraisal of the studies was not conducted; however, this is not necessarily needed for scoping reviews.6 It is important to highlight, however, that two of the studies were not specifically designed as research projects.

Conclusion

The multiplicity of loss associated with pandemics impact upon cultural norms, rituals, and usual social practices related to death and mourning, potentially increasing the risk of complicated grief. A focus on promoting connection with people before and after the death, adapting rituals and mourning practice in a respectful manner, and planning for a coordinated response to postbereavement support is recommended.

Disclosures and Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Matt Cooper, Outreach Liaison Librarian, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, for his contributions into the search strategy and supporting the conduct of the initial screening.

Authorship: Catriona R. Mayland, Nancy Preston, and Sheila Payne conceived and designed the study. Catriona R. Mayland and Andrew J.E. Harding completed all the searches, conducted the screening, extracted data, and conducted the initial analysis. All authors contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data. Catriona R. Mayland drafted the manuscript. All authors provided input into the manuscript and approved the submitted version.

This research did not receive any specific grant. Catriona R. Mayland is funded by Yorkshire Cancer Research, United Kingdom.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Etkind S.N., Bone A.E., Lovell N. The role and response of palliative care and hospice services in epidemics and pandemics: a rapid review to inform practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burke L.A., Neimeyer R.A. Prospective risk factors for complicated grief: a review of the empirical literature. In: Stroebe M., Schut H., van den Bout J., editors. Complicated grief: Scientific foundations for health care professionals. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2013. pp. 145–161. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miyajima K., Fujisawa D., Yoshimura K. Association between quality of end-of-life care and possible complicated grief among bereaved family members. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:1025–1031. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright A.A., Zhang B., Ray A. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sealey M., Breen L.J., O’Connor M. A scoping review of bereavement risk assessment measures: implications for palliative care. Pall Med. 2015;29:577–589. doi: 10.1177/0269216315576262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joanne Briggs Institute. https://wiki.joannabriggs.org/site/JGW - last Available from.

- 7.Thomas J., Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leong I.Y., Lee A.O., Ng T.W. The challenges of providing holistic care in a viral epidemic: opportunities for palliative care. Pall Med. 2004;18:12–18. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm859oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grimaud J., Legahneur F. Community beliefs and fears during a cholera outbreak in Haiti. Intervention. 2011;9:26–34. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rabelo I., Lee V., Fallah M.P. Psychological distress among Ebola survivors discharged from an Ebola treatment unit in Monrovia, Liberia – a qualitative study. Front Public Health. 2016;4:142. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwerdtle P.M., De Clerck V., Plummer V. Experience of Ebola Survivors: causes of distress and sources of resilience. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2017;32:234–239. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X17000073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamara S., Walder A., Duncan J. Mental health care during the Ebola virus outbreak in Sierra Leone. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95:842–847. doi: 10.2471/BLT.16.190470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James P.B., Wardle J., Steel A. Post-Ebola psychosocial experiences and coping mechanisms among Ebola survivors: a systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2019;24:671–691. doi: 10.1111/tmi.13226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ayers T., Balk D., Bolle J. Report on bereavement and grief research. Death Stud. 2004;28:491–575. doi: 10.1080/07481180490461188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bracken P.J., Giller J.E., Summerfield D. Psychological responses to war and atrocity: the limitations of current concepts. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40:1073–1082. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00181-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sque M., Long T., Payne S. The UK postmortem organ retention crisis: a qualitative study of its impact on parents. J R Soc Med. 2008;101:71–77. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2007.060178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]