To the Editor:

Over the past few months, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has provided an unprecedented challenge to critical care teams across the world. As the number of cases increases exponentially, we are seeing an unparalleled strain on intensive care resources.

To ensure optimal patient care, rapid, reliable, and low-risk diagnostic imaging is required. Although computed tomography can aid with diagnosis, the volume of critically unwell and highly infective patients means mass computed tomography scanning is unlikely to be a safe or practical approach. The critical care community thus has acknowledged the importance of point-of-care ultrasonography (POCUS) in the management of COVID-19, specifically lung ultrasound (US) and transthoracic echocardiography.

Current reports of lung US findings secondary to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection appear to demonstrate a correlation to disease stage and phenotype (Fig 1 ). Italian intensivist Gio Volpicelli also described its sensitivity in identifying COVID-19, even in patients for whom reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction swabs returned negative (personal communication, April 2020). The precise protocol for lung POCUS still is debated, with the current UK Intensive Care Society guidelines suggesting a 6-view approach (apical, baso-anterior, and posterior-lateral views bilaterally) and providing advice regarding probe decontamination.1 , 2

Fig. 1.

Lung findings in COVID-19: (i) coalescent B-lines (comet tail–like artifacts), a commonly reported finding in COVID-19; (ii) pleural effusion (E) with associated subpleural consolidation (C); (iii) densely consolidated lung (C) in a patient with COVID-19; and (iv) large pleural effusion (E). COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

In early disease, initial findings include the presence of focal B-lines interspersed with areas of healthy lung and A-lines.1 An irregular and thickened pleura with subpleural consolidation also may be seen.3 If there is no oxygen requirement, these patients may be suitable for discharge.2

In moderate disease, an increased number of confluent B-lines may be visible, with loss of A-lines (video 1). Such patients are likely to require supplementary oxygen and admission. These patients may fit the L phenotype and require moderate positive end-expiratory pressure ventilation strategies with conservative fluid balance.2, 3, 4

As the disease progresses, lobar and translobar consolidation may be seen, with the possibility of associated pleural effusions (large effusions are rare and a poor prognostic indicator) (video 2). These patients are likely to require critical care admission and appear to fit the H phenotype, with high positive end-expiratory pressure, early proning, and conservative fluid strategies possibly beneficial.2, 3, 4 The dynamic nature of this disease does, however, mean we need to remain malleable with the aforementioned described patterns and our treatment strategies.

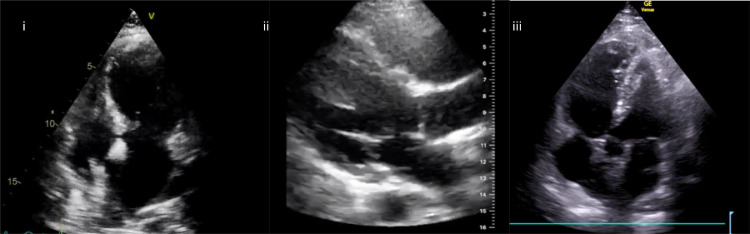

When considering echocardiographic findings in COVID-19, numerous mechanisms of cardiac injury have been described (Fig 2 ). These include myocarditis, global cardiac dysfunction, right ventricular failure, and acute myocardial infarction (AMI) (video 4). The European Society of Cardiology guidance on COVID-19 echocardiography advises only patients with cardiovascular compromise should be scanned, and these scans should be focused in nature (Table 1 ).5

Fig. 2.

Echocardiographic findings in COVID-19: (i) apical 4-chamber view—apical bowing in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy secondary to COVID-19; (ii) parasternal long-axis view—dilated right ventricle with septal bowing in a patient with COVID-19 and raised pulmonary pressures; and (iii) apical 5-chamber view—McConnell’s sign in a patient with COVID-19 and bilateral pulmonary emboli. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Table 1.

Summary of EACVI Guidance on Echocardiographic Data in Patients With COVID-195

| Structure | Suggested Method of Assessment |

| Left ventricle | Assessment of ejection fraction, for regional wall motion abnormalities and end-diastolic cavity diameter |

| Right ventricle | Assessment of global function—either tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion or fractional area change, EDD, and quantification of tricuspid regurgitation pressure gradient |

| Valves | Only a gross assessment of valvular function to be made unless detailed assessment specifically required |

| Pericardium | A focused assessment for presence of pericardial effusion or thickening |

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; EACVI, European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging; EDD, end-diastolic diameter.

Myocarditis may occur secondary to the abundance of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors on cardiac myocytes—the binding site for SARS-CoV2—with echocardiographic findings described in myocarditis including: (1) global or regional left ventricular dysfunction (possibly resulting in misdiagnosis as AMI), (2) right ventricular dysfunction, (3) apparent left ventricular hypertrophy (secondary to interstitial edema), and (4) ventricular thrombi.6

Right ventricular failure may be present as a result of raised pulmonary pressures (secondary to associated lung pathology, high ventilatory pressures, or pulmonary thrombi), myocarditis, or systemic hyperinflammation. Echocardiographic findings include right ventricular dilation with impaired systolic function (video 3).

Global ventricular dysfunction and Takotsubo cardiomyopathy also have been observed, presenting with a similar picture to that seen in septic cardiomyopathy (video 5). This is possibly a consequence of the hyperinflammatory stage of COVID-19 and is likely reversible.5 , 7

Acute myocardial infarction with associated regional wall motion abnormalities also may occur. These can either be type-1 AMIs, as a result of infection-driven plaque rupture, or type-2 AMIs, as a result of insufficient myocardial perfusion.

Transesophageal echocardiography is another useful imaging modality in COVID-19. Often this patient group has difficult transthoracic echocardiography windows, and thus transesophageal echocardiography provides alternative (and often much clearer) cardiac views. Its use, however, may be limited by availability of skilled users and equipment and the significant potential for aerosolization.8

POCUS also may have a role to play in management of COVID-19–associated cardiac arrest, as is recognized in the non-COVID-19 population.9 Barriers to its use are universal to scanning any patients with SARS-CoV2 infection undergoing aerosol-generating procedures, namely the use of personal protective equipment and challenges around disinfecting equipment.10

Proposals regarding upskilling of the current workforce and rapid POCUS education also have been made, with a wealth of online and published resources becoming available.10

In summary, in the face of a global pandemic, the ability to assess and triage patients in a rapid and reproducible manner is vital. When combined with clinical history and examination, POCUS provides a dynamic and low-risk tool to help guide diagnosis and management. We thus feel that the use of lung US and echocardiography should be included in the clinical assessment and management of patients with COVID-19.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.jvca.2020.05.009.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Confluent B lines, subpleural consolidation and thickened pleura in COVID-19.

Dense upper lobe consolidation in a patient with COVID-19.

Dilated right ventricle in a patient with COVID-19.

Hyperdynamic left ventricle in a patient with COVID-19.

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in a patient with COVID-19.

References

- 1.Lichtenstein DA, Mezière GA. The BLUE-points: Three standardized points used in the BLUE-protocol for ultrasound assessment of the lung in acute respiratory failure. Crit Ultrasound J. 2011;3:109–110. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Focused Ultrasound in Intensive Care (FUSIC). FUSIC lung COVID-19. Available at: https://www.ics.ac.uk/ICS/FUSIC/ICS/FUSIC/FUSIC_Accreditation.aspx?hkey=c88fa5cd-5c3f-4c22-b007-53e01a523ce8.

- 3.Huang Y, Wang S, Liu Y. A preliminary study on the ultrasonic manifestations of peripulmonary lesions of non-critical novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) SSRN Electronic J. 2020 doi: 10.21203/rs.2.24369/v1. [e-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gattinoni L, Chiumello D, Caironi P. COVID-19 pneumonia: Different respiratory treatment for different phenotypes? Intensive Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06033-2. (Accessed: 12 April 2020) [e-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skulstad H, Cosyns B, Popescu BA. COVID-19 pandemic and cardiac imaging: EACVI recommendations on precautions, indications, prioritization, and protection for patients and health care personnel. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020 doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jeaa072. (Accessed: 12 April 2020). [e-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeserich M, Konstantinides S, Pavlik G. Non-invasive imaging in the diagnosis of acute viral myocarditis. Clin Res Cardiol. 2009;98:753–763. doi: 10.1007/s00392-009-0069-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zheng YY, Ma YT, Zhang JY. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17:259–260. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0360-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsai SK. The role of transesophageal echocardiography in clinical use. J Chin Med Assoc. 2013;76:661–672. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2013.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zafiropoulos A, Asrress K, Redwood S. Critical care echo rounds: Echo in cardiac arrest. Echo Res Pract. 2014;1:D15–21. doi: 10.1530/ERP-14-0052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith MJ, Hayward SA, Innes SM. Point-of-care lung ultrasound in patients with COVID-19 – a narrative review. Anaesthesia. 2020 doi: 10.1111/anae.15082. (Accessed: 12 April 2020). [e-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Confluent B lines, subpleural consolidation and thickened pleura in COVID-19.

Dense upper lobe consolidation in a patient with COVID-19.

Dilated right ventricle in a patient with COVID-19.

Hyperdynamic left ventricle in a patient with COVID-19.

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in a patient with COVID-19.