On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), a worldwide pandemic. Severe acute respiratory failure due to SARS-CoV-2 requiring invasive mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit is associated with high mortality.1, 2, 3 Patient self-inflicted lung injury and ventilator-associated lung injury potentially could exacerbate lung inflammation and biotrauma, increasing further the mortality of that very sick patient population.4 More than 1 clinical phenotypes with different radiological and pulmonary mechanics profiles have been described recently.5 Identifying the clinical phenotype and applying principles of precision medicine to ventilatory management theoretically could be beneficial. Lung ultrasound (LUS) potentially could be an invaluable diagnostic tool in guiding therapy and assessing response to therapy, as SARS-CoV-2 pneumonitis demonstrates particular features on LUS at different stages of the disease, which may require individualized ventilatory management.6 , 7

Role of LUS in Critical Care

Critically ill patients need rapid access to accurate and reproducible imaging techniques to diagnose pathology and implement and monitor treatment. Point-of-care ultrasound has been established firmly in the acute and critical care settings, with the development of the Intensive Care Society Focused Ultrasound Intensive Care accreditation process in the United Kingdom.

The COVID-19 pandemic has pushed LUS to the forefront as an important tool in the assessment of patients with COVID-19. Lung ultrasound has a higher diagnostic accuracy than physical examination and chest radiography combined.8

For many years, direct sonographic evaluation of lung parenchyma was considered inaccessible because of the presence of air. The high acoustic mismatch between the lung air and adjacent extrapulmonary tissue creates a complete reflection of the ultrasound beam, and creates an ultrasound image of air artifacts without any discernable imaging of the lung parenchyma.9 However, it is now recognized that pathology of the lung creates distinct artifacts that can be used to diagnose pathology and guide therapy.

Lung US has proved to be useful in the evaluation of many different acute conditions, namely cardiogenic pulmonary edema, acute lung injury, pneumothorax, pneumonia, and pleural effusions. With the appropriate training and supervision, the intensivist can use ultrasound to diagnose lung pathology rapidly, as well as plan and monitor therapy in real time.

Pulmonary Mechanics Profile in COVID-19–Associated Lung Injury

Reports from Italy and China highlighted variation in respiratory mechanics profiles among invasively ventilated patients with COVID-19 pneumonitis.4 , 7 , 10 Gattinoni et al recently have identified 2 clinical phenotypes: (1) type L, characterized by Low elastance (near-normal compliance), low ventilation- to- perfusion ratio, low lung weight (predominantly ground-glass changes on computed tomography [CT]), and low recruitability (due to minimal non-aerated lung)4 , 10; and (2) type H, characterized by high elastance (reduced compliance), high right- to- left shunt (caused by cardiac output perfusing non-aerated edematous lung), high lung weight (mimicking acute respiratory distress syndrome [ARDS)], and high recruitability (as in severe ARDS).4 , 10 The aforementioned observations indicate that not all patients with COVID-19 and severe acute respiratory failure have Berlin ARDS, and therefore blind implementation of ARDS-oriented open lung ventilatory strategy potentially could be harmful.11A personalized lung-protective ventilatory approach tailored to lung mechanics therefore should be considered.

LUS Patterns in COVID-19–Associated Lung Injury and Ventilation Strategies

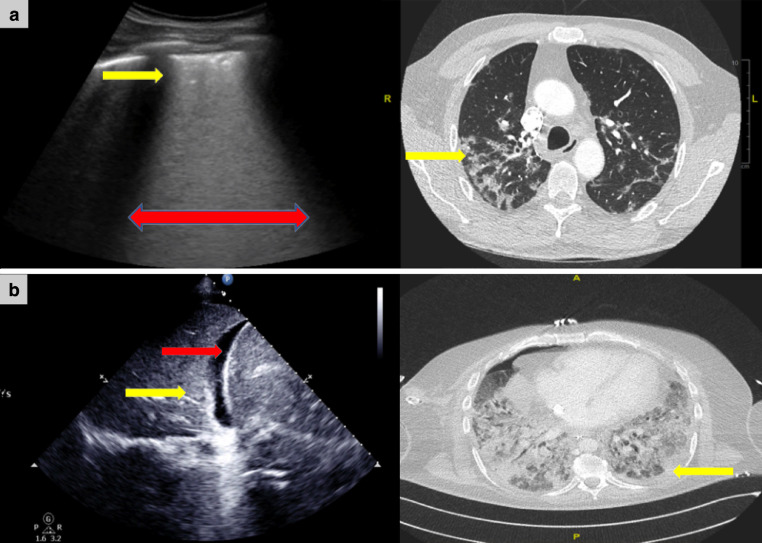

Apart from pulmonary mechanics (elastance/compliance and recruitability), the 2 clinical phenotypes ideally should be confirmed radiologically on CT (L phenotype: subpleural ground glass with minimal non-aerated lung volume [Fig 1 , A]; H phenotype: ARDS-type features [Fig 1, B]).4 , 10 In a pandemic surge, however, transportation of critically ill invasively ventilated patients to radiology is challenging. This is in part due to the logistics of transferring the sheer volume of patients out of hot zones and the risk of exposure and transmission that this involves. Our colleagues in both China and Italy have found LUS to be a suitable alternative to CT in times when rapid diagnosis, triage, and evaluation of ventilation strategies are required, and when CT is not a feasible option.12, 13, 14 However, the main reason LUS has been the favored imaging modality is due to its ability to identify and evaluate serially progression or indeed resolution of superficial pathology; in particular, the lung signs and patterns we now know to be characteristic of SARS-CoV-2.12

Fig 1.

Lung ultrasound and thoracic computed tomography of a patient with COVID-19 pneumonitis requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. (A) Left image is LUS of the lateral chest wall demonstrating thickened pleural line with evidence of subpleural consolidation (yellow arrow). The entire intercostal space is filled with coalescent B-line artifact (red arrow); this is consistent with pattern 1. The right image is a CT thorax demonstrating patches of peripheral ground-glass changes (yellow arrow), which would account for the LUS appearances. Note that most of the lung is aerated, consistent with the L phenotype. (B) Left image is a LUS in the posterolateral zone, demonstrating hepatization of the lung (yellow arrow) consistent with pattern 2. Note the small anechoic space between the lung edge and the diaphragm; this represents a small parapneumonic effusion (red arrow). The right image is a thoracic CT demonstrating bilateral extensive consolidation consistent with ARDS and the H phenotype. The yellow arrow denotes the area the LUS is performed and the CT changes that account for the LUS appearances. ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CT, computed tomography; LUS, lung ultrasound.

Characteristic sonographic findings, first described by Chinese intensivists, with consensus from clinicians of other affected countries, include (1) thickened, irregular pleural line; (2) B-lines (focal, multifocal, and diffuse); (3) consolidation varying from focal, nontranslobar to translobar with or without air bronchograms; (4) A-lines, indicating air under the pleural line, during the recovery phase; and (5) pleural effusions (less common).8 , 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 B-lines are a form of reverberation artifact, produced as a result of the interaction between ultrasound as it encounters a mix of fluid and air.8 , 17

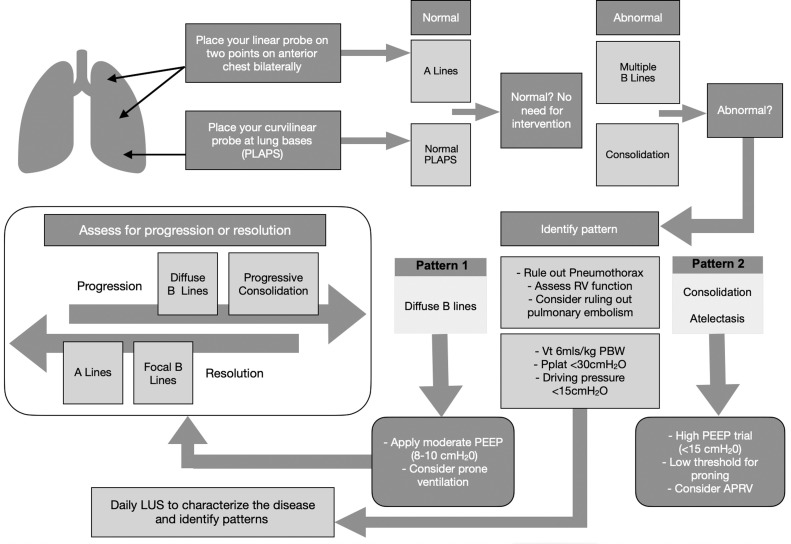

Intensivists from Northern Italy described 2 distinctive sonographic LUS patterns.18 These patterns potentially can be used to differentiate patients who respond to high positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) as an initial management strategy from patients who would benefit from moderate PEEP or mechanical ventilation in the prone position.

Pattern 1

Pattern 1 shows diffuse or coalescent B-line artifact descending from the pleural line to the bottom of the scan sector without fade, moving in concert with the sliding pleura.19 In COVID-19 pneumonitis, this pattern likely is caused by local subpleural inflammation/interstitial edema (“ground-glass” lesions) on CT (Fig 1, A).4 , 10 , 20 These sonographic features correlate with the “L phenotype” described by Gattinoni et al and do not fit ARDS criteria.4 , 11 Moderate levels of PEEP (8-10 cmH2O) would be an appropriate initial strategy in this situation given that lung mechanics are preserved, there is limited recruitability, and hypoxemia is assumed to be caused mainly by deregulated pulmonary perfusion.4 , 10 High PEEP (10-15 cmH2O) or alveolar recruitment maneuvers could lead to overdistention and cardiovascular instability and should not be used as a first-line measure. Prone ventilation should be considered in refractory cases. Response to proning and its physiological efficacy in this group of patients likely is related to redistribution of blood flow and offloading of the right ventricle rather than homogenous distribution of transpulmonary pressure and recruitment (Fig 2 ).4 , 10 , 21 , 22

Fig 2.

Proposed LUS algorithm for assessment and ventilatory management of COVID-19 severe acute respiratory failure. Part of this algorithm is a modified version of the Intensive Care Society FUSIC LUS dataset created by H. Conway (co-author).15 APRV, airway pressure release ventilation; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; FUSIC, Focused Ultrasound Intensive Care; LUS, lung ultrasound; PBW, predicted body weight; PEEP, positive-end expiratory pressure; PLAPS, posterolateral alveolar and/or pleural syndrome; Pplat, plateau pressure; RV, right ventricle; Vt, tidal volume.

Pattern 2

Pattern 2 typically displays significant basal consolidation in the posterior lateral zone referred to as “"lung hepatization” due to its appearance of the liver. The lung tissue in this region is completely deaerated, either due to extensive atelectasis or a pneumonic process.23 The anterior zones tend to be spared and therefore signs of aeration may be present (Fig 1, B). This pattern of lung injury (H phenotype) resembles ARDS, and those patients may benefit from high levels of PEEP and prone positioning (Fig 2).4 , 16 , 21

In both patterns, use of low- tidal- volume ventilation (6 mL/kg predicted body weight) and low plateau and driving pressures (less than 30 and 15 cmH2O, respectively) to reduce the risk of ventilator-associated lung injury is paramount.24 It has been argued that patients with the L phenotype profile (pattern 1 on LUS) can be ventilated safely with higher tidal volumes (7-8 mL/kg predicted body weight) given the preserved respiratory system compliance (resulting in lower plateau and driving pressures).25 The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network trial, however, demonstrated that patients with ARDS can have preserved pulmonary compliance and that this subgroup of patients still would benefit from low volume/low pressure ventilation.24 It therefore would be prudent to avoid use of liberal tidal volumes in mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19 and injured lungs.

Daily LUS can be used to assess disease progression; transition between patterns and phenotypes; and aid prognostication, decision-making, and modification of ventilation strategies. In theory, LUS can be used to assess reaeration and tissue recruitment (A-lines/A-profile resolution) in response to high PEEP or proning where appropriate; however, this should be interpreted with caution, taking into account changes in pulmonary mechanics and oxygenation markers since subtle sonographic changes may not be clinically evident or significant.

Conclusion

The pathophysiology of COVID-19–associated lung injury is not well understood. The concept of different phenotypes is hypothesis- generating and not based on rigorous data supporting differences in treatment. It is quite possible that there are more than 2 physiological models and patterns and that L and H represent the extremes of a very heterogenous disease spectrum. Lung ultrasound is an invaluable tool in the intensivist's armory that can be used to characterize COVID-19 lung disease and its natural history and individualize ventilation strategies. Prospective research comparing LUS-guided care versus standard ventilatory management of patients with COVID-19 lung injury is needed before any changes in practice are imposed.

Conflict of Interest

H. Conway is a Focused Ultrasound in Intensive Care UK Committee Member, Intensive Care Society, London, UK.

References

- 1.Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-center retrospective observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:475–481. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. Accessed April 25, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Livingston E, Bucher K. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Italy [e-pub ahead of print] JAMA. 2020 Mar 17 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4344. Accessed April 25, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MunsWu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention [e-pub ahead of print] JAMA. 2020 Feb 24 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gattinoni L, Chiumello D, Caironi P. COVID-19 pneumonia: different respiratory treatments for different phenotypes? [e-pub ahead of print] Intensive Care Med. 2020 Apr 14 doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06033-2. Accessed April 26, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brochard L, Slutsky A, Pesenti A. Mechanical ventilation to minimize progression of lung injury in acute respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:438–442. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201605-1081CP. Accessed April 16 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith MJ, Hayward SA, Innes SM. Point-of-care lung ultrasound in patients with COVID-19 - a narrative review [e-pub ahead of print] Anaesthesia. 2020 Apr 10 doi: 10.1111/anae.15082. Accessed April 16 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pan C, Chen L, Lu C. Lung recruitability in COVID-19- associated acute respiratory distress syndrome: A single-center observational study [e-pub ahead of print] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 May 15 doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0527LE. Accessed April 18 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lichtenstein DA, Meziere GA. Relevance of lung ultrasound in the diagnosis of acute respiratory failure: The BLUE protocol. Chest. 2008;134:117–125. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Volpicelli G. Lung sonography. J Ultrasound Med. 2013;32:165–171. doi: 10.7863/jum.2013.32.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gattinoni L, Coppola S, Cressoni M. COVID-19 does not lead to a “typical” acute respiratory distress syndrome [e-pub ahead of print] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:1299–1300. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0817LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ARDS Definition Task Force. Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: The Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peng QY, Wang XT, Zhang LN. Findings of lung ultrasonography of novel corona virus pneumonia during the 2019-2020 epidemic [e-pub ahead of print] Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:849–850. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05996-6. Accessed April 26, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang Y, Wang S, Liu Y. A preliminary study on the ultrasonic manifestations of peripulmonary lesions of non-critical novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) [e-pub ahead of print] SSRN. 2020 Feb 26 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3544750. Accessed April 26, 2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Volpicelli C, Lamorte A, Villén T. What's new in lung ultrasound during the COVID-19 pandemic [e-pub ahead of print] Intensive Care Medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06048-9. Accessed April 26, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Intensive Care Society. FUSIC guidance for lung ultrasound during COVID-19. Available at: https://www.ics.ac.uk/ICS/ICS/FUSIC/FUSIC_COVID-19.aspx. Accessed April 22, 2020.

- 16.Fiala MJ. A brief review of lung ultrasound in COVID-19: Is it useful? [e-pub ahead of print] Ann Emerg Med. 2020 Apr 8 doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.03.033. Accessed April 19, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lichtenstein DA. Lung ultrasound in the critically ill. Ann Intensive Care. 2014;4:1. doi: 10.1186/2110-5820-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Italian Group for the Evaluation of Interventions in Intensive Care Medicine (GIVITI) COVID-19 webinar. Available at:https://giviti.marionegri.it/covid-19-en/. Accessed March 10, 2020.

- 19.Volpicelli G, Elbarbary M, Blaivas M. International evidence-based recommendations for point-of-care lung ultrasound. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:577–579. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2513-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Volpicelli G, Mussa A, Garofalo G. Bedside lung ultrasound in the assessment of alveolar-interstitial syndrome. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24:689–696. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guerin C, Reignier J, Richard JC. Prone positioning in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2159–2168. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vieillard-Baron A, Charron C, Caille V. Prone positioning unloads the right ventricle in severe ARDS. Chest. 2007;132:1440–1446. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parlamento S, Copetti R, Di Bartolomeo S. Evaluation of lung ultrasound for the diagnosis of pneumonia in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27:379–384. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. Brower RG, Matthay MA. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1301–1308. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marini JJ, Gattinoni L. Management of COVID-19 respiratory distress [e-pub ahead of print] JAMA. 2020 Apr 24 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6825. Accessed April 26, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]