Hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) infection are at a high risk of progressive respiratory failure, endotracheal intubation, and mortality. The pathophysiology of COVID-19 infection has not been elucidated, but cytokine storm, prothrombotic state, and myocardial dysfunction have been implicated (1). Echocardiography is an essential bedside tool, which allows noninvasive assessment of biventricular function in COVID-19 patients, and echocardiographic findings can significantly influence decision making in the appropriate clinical settings (2). We aimed at studying the association of in-hospital mortality with right ventricular (RV) size measured by a focused, time-efficient echocardiography protocol (2).

In this retrospective study, we enrolled consecutive patients hospitalized to Mount Sinai Morningside Hospital (New York, New York) due to COVID-19 infection who underwent clinically indicated echocardiograms from March 26, 2020 to April 22, 2020. Echocardiograms were performed adhering to a focused, time-efficient protocol with appropriate use of personal protective equipment and limited viral exposure time. Portable ultrasound machines were used: CX50 (Philips Medical Systems, Bothell, Washington) and Vivid S70 (GE Healthcare Systems, Milwaukee, Wisconsin). Echocardiographic studies were interpreted by experienced, board-certified echocardiography attending physicians. RV dilation was defined as basal diastolic RV diameter exceeding 4.1 cm in the right ventricle–focused apical view and/or basal right-to-left ventricular diameter ratio of ≥0.9 in the apical 4-chamber view, and confirmed by visual RV inspection in all obtained views. In-hospital mortality was the study outcome. The comparisons were performed using Student’s t-test or the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables, and the chi-square test for categorical variables. Univariate and multivariate regression analysis was used to explore the associations of clinical and echocardiographic variables with mortality. The study protocol was approved by the Mount Sinai Institutional Review Board.

Echocardiograms of 110 consecutive patients were reviewed, and 5 were excluded due to inadequate study quality. The mean age was 66.0 ± 14.6 years, and 38 (36%) patients were women. Thirty-one (30%) patients were intubated and mechanically ventilated at the time of the echocardiographic examination. RV dilation was present in 32 (31%) patients. Patients with RV dilation did not have significant differences in the prevalence of major comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, and known coronary artery disease), laboratory markers of inflammation (white blood cell count, C-reactive protein), or myocardial injury (troponin I) but were more likely to have renal dysfunction (creatinine >1.5 mg/dl; 72% vs. 41%; p = 0.01) compared with patients without RV dilation. There were no differences between the groups in the use of therapeutic anticoagulation (38% vs. 39%; p = 0.83) at the time of the echocardiographic examination. Similarly, there were no differences in the measures of left ventricular size and function between the groups (mean left ventricular ejection fraction 54% vs. 55%; p = 0.61). RV hypokinesis (66% vs. 5%; p = 0.01) and moderate or severe tricuspid regurgitation (21% vs. 7%; p = 0.05) were more prevalent in patients with RV enlargement. Computed tomography angiography of the chest was obtained in 10 (31%) patients with RV enlargement, and 5 patients had evidence of pulmonary embolism. At the end of the study period, 21 (20%) patients died: 13 (41%) deaths were observed in patients with RV dilation, with 8 (11%) observed in patients without RV dilation (Figure 1 ). On univariate analysis, mechanical ventilation (p = 0.003), vasoactive medication use (p = 0.007), and RV enlargement (p = 0.001) were significantly associated with mortality. On multivariate analysis, RV enlargement was the only variable significantly associated with mortality (odds ratio: 4.5; 95% confidence interval: 1.5 to 13.7; p = 0.005).

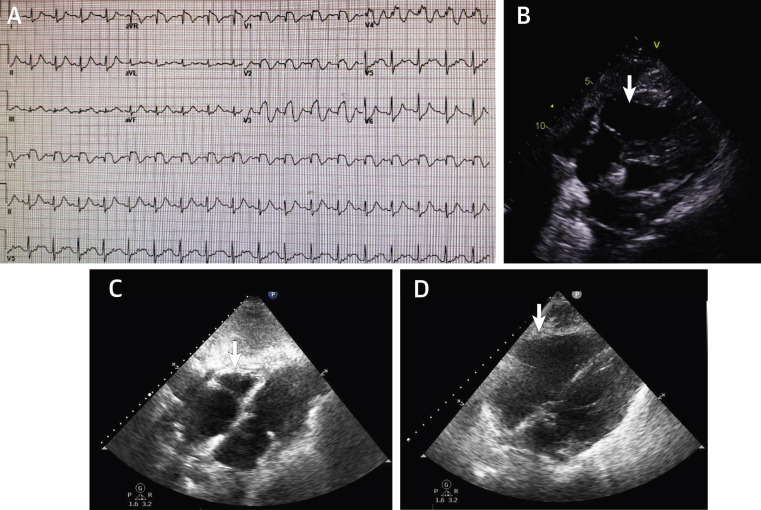

Figure 1.

Right Ventricular Dilation in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19 Infection

Patient #1, intubation day 7, not on therapeutic anticoagulation, with rapid hemodynamic deterioration. (A) Electrocardiography shows sinus tachycardia with ST-segment elevation in leads V1 to V4. (B) Echocardiography in the same patient shows right ventricular dilation (arrow), with a small hyperkinetic left ventricle in the modified subcostal view. The patient expired. Patient #2, intubation day 5, on therapeutic anticoagulation. (C) Echocardiography shows normal-size right ventricle (arrow) in the modified subcostal view. (D) The same patient 3 days later, with rapid hemodynamic deterioration. Echocardiography shows right ventricular dilation (arrow) in the modified subcostal view. The patient expired. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease-2019.

This is a small, retrospective, single-center study from the epicenter city of COVID-19 infection. None of the studies were performed in prone position.

In conclusion, RV dilation was prevalent in the current study of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 infection using a focused, time-efficient echocardiography protocol. The mechanism of RV dilation is likely multifactorial and includes thrombotic events, hypoxemic vasoconstriction, cytokine milieu, and direct viral damage. RV dilation was strongly associated with in-hospital mortality in these patients.

Footnotes

The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the JACC: Cardiovascular Imagingauthor instructions page.

References

- 1.Clerkin K.J., Fried J.A., Raikhelkar J. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2020;141:1648–1655. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirkpatrick J.N., Mitchell C., Taub C., Kort S., Hung J., Swaminathan M. ASE Statement on protection of patients and echocardiography service providers during the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:3078–3084. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]