As of May 6, 2020, nearly 3·7 million people have been infected and around 260 000 people have died from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) worldwide.1 Almost all COVID-19-related serious consequences feature pneumonia.2 In the first large series of hospitalised patients (n=138) with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, chest CT showed bilateral ground glass opacities with or without consolidation and with lower lobe predilection in all patients.3 In this series, 36 (26%) patients required intensive care, of whom 22 (61%) developed acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).3 The mechanisms through which severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) causes lung damage are only partly known, but plausible contributors include a cytokine release syndrome triggered by the viral antigen, drug-induced pulmonary toxicity, and high airway pressure and hyperoxia-induced acute lung injury secondary to mechanical ventilation. To date, about 1·2 million people worldwide have recovered from COVID-19, but there remains concern that some organs, including the lungs, might have long-term impairment following infection (figure ). No post-discharge imaging or functional data are available for patients with COVID-19.

Figure.

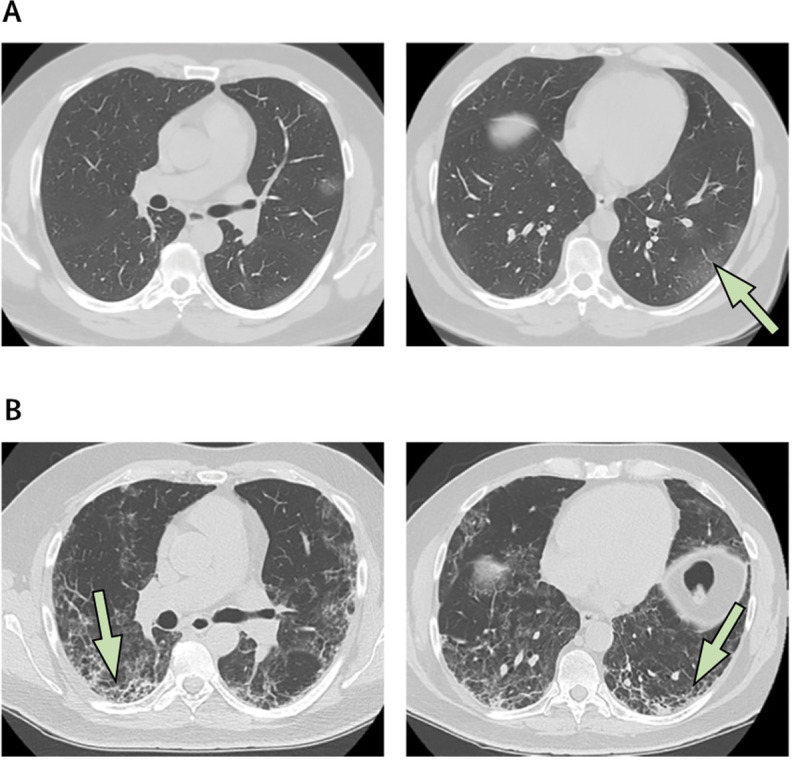

Lung CT of a patient with coronavirus disease 2019

(A) Images of peripheral mild ground glass opacities in the left lower lobe (arrow). (B) Three weeks later, at the same lung zones, the disease has rapidly progressed and fibrotic changes are now evident (arrows).

Other strains of the coronavirus family, namely severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV; known as SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV; known as MERS), are genetically similar to SARS-CoV-2 and cause pulmonary syndromes similar to COVID-19. At the end of the SARS epidemic in June, 2003, 8422 individuals were affected and 916 died; whereas MERS, which was first identified in April, 2012, has infected 2519 individuals worldwide to date, including 866 deaths.4 The predominant CT abnormalities in patients with SARS included rapidly progressive ground glass opacities sometimes with consolidation. Reticular changes were evident approximately 2 weeks after symptom onset and persisted in half of patients beyond 4 weeks.5 However, a 15-year follow-up study of 71 patients with SARS showed that interstitial abnormalities and functional decline recovered over the first 2 years following infection and then remained stable. At 15 years, 4·6% (SD 6·4%) of the lungs showed interstitial abnormality in patients who had been infected with SARS.6 In patients with MERS, typical CT abnormalities included bilateral ground glass opacities, predominantly in the basal and peripheral lung zones. Follow-up outcomes are less well described in patients with MERS. In a study of 36 patients who had recovered from MERS, chest x-rays taken a median of 43 (range 32–320) days after hospital discharge showed abnormalities described as lung fibrosis in about a third of the patients.7 Longer-term follow-up of patients who recovered from MERS has not been reported.

Pulmonary fibrosis can develop either following chronic inflammation or as a primary, genetically influenced, and age-related fibroproliferative process, as in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). Pulmonary fibrosis is a recognised sequelae of ARDS. However, most follow-up studies—which have included both physiological measures and chest CT—have shown that persistent radiographic abnormalities after ARDS are of little clinical relevance and have become less common in the era of protective lung ventilation.8 Available data indicate that about 40% of patients with COVID-19 develop ARDS, and 20% of ARDS cases are severe.9 Of note, the average age of patients hospitalised with severe COVID-19 appears to be older than that seen with MERS or SARS, which is perhaps a consequence of wider community spread. In inflammatory lung disorders, such as those associated with autoimmune disease, advancing age is a risk factor for the development of pulmonary fibrosis. Given these observations, the burden of pulmonary fibrosis after COVID-19 recovery could be substantial.

Progressive, fibrotic irreversible interstitial lung disease, which is characterised by declining lung function, increasing extent of fibrosis on CT, worsening symptoms and quality of life, and early mortality,10 arises, with varying degrees of frequency, in the context of a number of conditions including IPF, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, autoimmune disease, and drug-induced interstitial lung disease. Although the virus is eradicated in patients who have recovered from COVID-19, the removal of the cause of lung damage does not, in itself, preclude the development of progressive, fibrotic irreversible interstitial lung disease. Furthermore, even a relatively small degree of residual but non-progressive fibrosis could result in considerable morbidity and mortality in an older population of patients who had COVID-19, many of whom will have pre-existing pulmonary conditions.

At present, the long-term pulmonary consequences of COVID-19 remains speculative and should not be assumed without appropriate prospective study. Nonetheless, given the huge numbers of individuals affected by COVID-19, even rare complications will have major health effects at the population level. It is important that plans are made now to rapidly identify whether the development of pulmonary fibrosis occurs in the survivor population. By doing this, we can hope to deliver appropriate clinical care and urgently design interventional trials to prevent a second wave of late mortality associated with this devastating pandemic.

Acknowledgments

PS reports grants, personal fees, and non-financial support from Roche, PPM Services, and Boehringer-Ingelheim and reports personal fees from Red X Pharma, Galapagos, and Chiesi, outside of the submitted work. PS reports that his wife is an employee of Novartis. SA reports grants and personal fees from Bayer Healthcare, Aradigm Corporation, Grifols, Chiesi, and INSMED and reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, Basilea, Zambon, Novartis, Raptor, Actavis UK, Horizon, outside of the submitted work. TMM reports, industry-academic funding from GlaxoSmithKline to his institution and reports consultancy or speaker fees from Apellis, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Blade Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Galapagos, GlaxoSmithKline, Indalo, Novartis, Pliant, Respivant, Roche, and Samumed. All other authors report no competing interests.

References

- 1.WHO Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report. 2020. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen

- 2.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. published online Feb 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases COVID-19, MERS & SARS. 2020. https://www.niaid.nih.gov/diseases-conditions/covid-19

- 5.Ooi GC, Khong PL, Müller NL. Severe acute respiratory syndrome: temporal lung changes at thin-section CT in 30 patients. Radiology. 2004;230:836–844. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2303030853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang P, Li J, Liu H. Long-term bone and lung consequences associated with hospital-acquired severe acute respiratory syndrome: a 15-year follow-up from a prospective cohort study. Bone Res. 2020;8:8. doi: 10.1038/s41413-020-0084-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Das KM, Lee EY, Singh R. Follow-up chest radiographic findings in patients with MERS-CoV after recovery. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2017;27:342–349. doi: 10.4103/ijri.IJRI_469_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burnham EL, Janssen WJ, Riches DW, Moss M, Downey GP. The fibroproliferative response in acute respiratory distress syndrome: mechanisms and clinical significance. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:276–285. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00196412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. published online March 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown KK, Martinez FJ, Walsh SLF. The natural history of progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Eur Respir J. 2020 doi: 10.1183/13993003.00085-2020. published online March 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]