Abstract

Objectives

TYK2 is a common genetic risk factor for several autoimmune diseases. This gene encodes a protein kinase involved in interleukin 12 (IL-12) pathway, which is a well-known player in the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis (SSc). Therefore, we aimed to assess the possible role of this locus in SSc.

Methods

This study comprised a total of 7103 patients with SSc and 12 220 healthy controls of European ancestry from Spain, USA, Germany, the Netherlands, Italy and the UK. Four TYK2 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (V362F (rs2304256), P1104A (rs34536443), I684S (rs12720356) and A928V (rs35018800)) were selected for follow-up based on the results of an Immunochip screening phase of the locus. Association and dependence analyses were performed by the means of logistic regression and conditional logistic regression. Meta-analyses were performed using the inverse variance method.

Results

Genome-wide significance level was reached for TYK2 V362F common variant in our pooled analysis ( p=3.08×10−13, OR=0.83), while the association of P1104A, A928V and I684S rare and low-frequency missense variants remained significant with nominal signals ( p=2.28×10−3, OR=0.80; p=1.27×10−3, OR=0.59; p=2.63×10−5, OR=0.83, respectively). Interestingly, dependence and allelic combination analyses showed that the strong association observed for V362F with SSc, corresponded to a synthetic association dependent on the effect of the three previously mentioned TYK2 missense variants.

Conclusions

We report for the first time the association of TYK2 with SSc and reinforce the relevance of the IL-12 pathway in SSc pathophysiology.

INTRODUCTION

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is an autoimmune disease that involves extensive fibrosis in the skin and different internal organs, abnormalities of the vascular system and immune imbalance with autoantibody production, particularly anticentromere autoantibodies (ACA) and antitopoisomerase autoantibodies (ATA). The aetiology of the disease is largely unknown, although both environmental and genetic factors are thought to be involved in the disease development.1

Large genetic studies, including genome-wide association studies and Immunochip analysis, have identified several immune-related loci underlying the susceptibility to SSc onset.2,3 Although great advances have been made over the last 7 years, our knowledge of SSc genetic background is still limited, and the numbers of convincingly SSc genetic markers only account for a small proportion of the total genetic variance for the disease.4,5 Thus, further genetic studies will help to better understand the pathogenic processes implicated in SSc development.

A recent fine-mapping genetic study of a common autoimmunity locus, TYK2-ICAM, in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) identified three TYK2 protein-coding variants as the most likely causal variants responsible for the signal of association in the region. The authors also extended the results into other autoimmune phenotypes, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and observed that the three variants are missense mutations predicted to be damaging using functional prediction tools.6

TYK2 encodes a tyrosine kinase member of the JAK-STAT family, and mediates signalling of different interleukin 12 (IL-12) family cytokines, such us IL-12 and IL-23. Several polymorphisms in this locus have been associated with other autoimmune diseases, such as psoriasis, multiple sclerosis, Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.7

Interestingly, SSc Immunochip study3 found suggestive, but not significant, evidence of association in TYK2 region ( p values ranging from 5×10−4 to 5×10−2). Moreover, different functional and genetic studies highlighted the special relevance of IL-12/STAT4 pathway in the disease pathophysiology.3,4,8,9 Thus, we performed a follow-up study to further investigate whether variations within this genomic region, including the three variants responsible for the association in RA and other autoimmune phenotypes, are also involved in SSc susceptibility.

METHODS

Study population

This study comprised a total of 7103 patients with SSc and 12 220 healthy controls of European ancestry. The 2118 patients with SSc and 4742 healthy controls from Spain and USA enrolled in the SSc Immunochip screening phase were obtained from the previously published SSc Immunochip study3 and additional Immunochip data for Spanish patients with SSc and healthy controls. The validation cohort included 4985 SSc cases and 7478 controls from independent case–control sets of European ancestry (Germany, the Netherlands, Italy, UK and USA).

Patients with SSc fulfilled the 1980 American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for this disease or the criteria proposed by LeRoy and Medsger for early SSc.10,11 In addition, patients were classified as having limited cutaneous SSc or diffuse cutaneous SSc as described in LeRoy et al.12 Patients were also subdivided by autoantibody status according to the presence of ACA or ATA.

Approval from the local ethics committees and written informed consent from all participants were obtained in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study design

SSc Immunochip screening phase

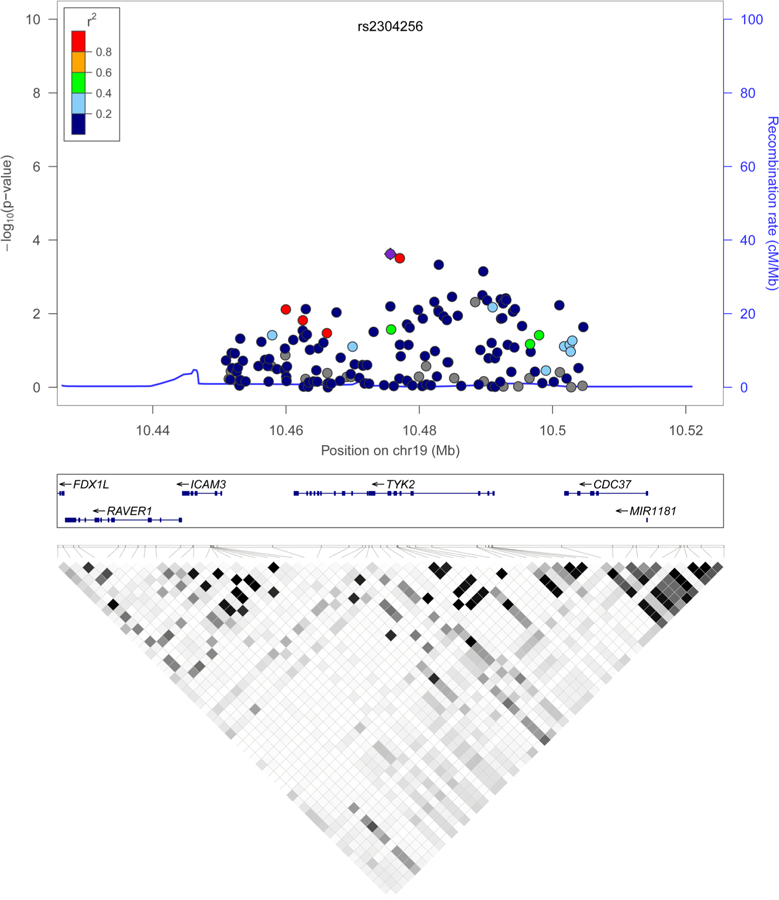

An initial evaluation of TYK2 region was performed in the SSc Immunochip screening phase. We included 30 kpb spanning the complete TYK2 gene and 10 kpb upstream and downstream from this locus, from base pair 10 450 993 to 10 504 616 in chromosome 19. The analysed genetic region comprised the linkage disequilibrium (LD) block that completely covers TYK2 (figure 1). Quality control filters and principal component analysis were applied as described in ref. 3. We performed single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotype imputation of the TYK2 region as implemented in IMPUTE2 with the use of the 1000 Genomes Phase 1 reference panel.13,14 After imputation, genotyping data for 154 SNPs were available.

Figure 1.

Association result plot for TYK2 region in the Immunochip screening phase. The p values for association (−log10 values) of each single-nucleotide polymorphism are plotted against their physical position on chromosome 19. The lower panel shows the linkage disequilibrium pattern at the TYK2 locus (r2 values are indicated by colour gradient).

Follow-up phase

Four TYK2 missense mutations were selected for validation in independent replication cohorts: one common coding variant (V362F (rs2304256)), two low-frequency coding variants (P1104A (rs34536443), I684S (rs12720356)) and one rare coding variant (A928V (rs35018800)). Finally, we performed meta-analysis for the selected SNPs combining the cohorts from both stages.

Genotyping methods

The genotyping of the SSc cases included in the validation cohorts was performed with both TaqMan SNP genotyping technology and Immunochip platform. For TaqMan genotyping system, we used TaqMan 5′ allele discrimination predesigned assays from Applied Biosystems in a LightCycler 480 Real-Time PCR System (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany). Genotyping call rate was >95% for all the SNPs. The Immunochip genotyping was performed on the Illumina iScan system, as per Illumina protocols, in the Centre for Genomics and Oncological Research (GENYO, Granada, Spain). Control genotyping data partially overlapped with those from previous Immunochip reports.15–23 If any of the four selected SNPs was missing in a dataset, imputation was applied. Genotype imputation was performed with IMPUTE2 using the 1000 Genomes Phase 1 reference panel.13,14 The correspondence between Immunochip (including imputed data) and TaqMan genotyping data was >98% for all the SNPs.

Data analysis

Associations of the SNPs with SSc were evaluated by logistic regression analysis in all the cohorts separately. Meta-analysis was performed with inverse-variance weighting under a fixed-effects model as implemented in PLINK V.1.07 software.24 The combined analysis, including the two phases of the study, was also performed using the inverse variance method based on population-specific logistic regression analyses. p Values <0.05 were considered statistically significant in the association analyses. Heterogeneity between the datasets was assessed using Cochran’s Q test. Q values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was tested for all the validation cohorts (HWE p values <0.01 were considered to show significant deviation from the equilibrium). None of the included control cohorts showed significant deviation from HWE for all the genotyped SNPs.

To test the independence of association between each SNP, we performed conditional logistic regression analyses as implemented in PLINK. To analyse the possible effect of A928V (rs35018800) in conditioning analysis, a generalised null linear model including population origin and two variants (P1104A (rs34536443) and I684S (rs12720356)) as covariates was compared against an alternative model including the same variables and A928V (rs35018800) variant by the means of a likelihood ratio test in R. We also assessed the different allelic combinations using PLINK. Allelic combinations with a frequency <0.5% were excluded from the analysis.

Regional association plot for TYK2 region was performed using LocusZoom V.1.1 software (http://csg.sph.umich.edu/locuszoom/).25 The HapMap Project phase I, II and III (CEU populations) was used to define the LD pattern across TYK2 region, and Haploview V.4.2 software (http://www.broadinstitute.org/haploview/haploview) was used to perform the LD plot. The statistical power of the combined analysis is shown in online supplementary table S1, and was calculated according to Power Calculator for Genetic Studies 2006 software under an additive model.26

RESULTS

SSc Immunochip initial screening

The initial screening of TYK2 region performed in the SSc Immunochip study showed several tier-two association signals at this locus (figure 1). A common protein-coding missense variant previously associated with SLE showed the strongest association with the disease (V362F (rs2304256) p value=2.39×10−4, OR=0.85).27–29 This variant and the three TYK2 protein-coding variants responsible for the association with RA and SLE according to Diogo et al6 were selected for follow-up in independent validation cohorts to confirm the suggestive evidence of association found in this locus with SSc.

Follow-up phase and meta-analysis

Pooled analysis, including the five validation cohorts, revealed significant associations for the four TYK2 SNPs with SSc at p<0.05 (see online supplementary table S2). The meta-analysis combining both steps showed that TYK2 V362F (rs2304256) variant achieved the genome-wide significance level ( p=3.08×10−13, OR=0.83), while P1104A (rs34536443), A928V (rs35018800) and I684S (rs12720356) remained with significant nominal p values ( p=2.28×10−3, OR=0.80; p=1.27×10−3, OR=0.59; p=2.63×10−5, OR=0.83, respectively) (table 1). No significant heterogeneity in the ORs among the seven cohorts was observed. The analyses carried out for the main SSc clinical features revealed that the observed association signal rely on the whole disease (data not shown).

Table 1.

Inverse variance meta-analysis of four TYK2 SNPs in seven different cohorts of patients with SSc and healthy controls (7103 patients with SSc and 12 220 controls)

| Inverse variance test |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chr | SNP | Minor/major | Comment | MAF cases | MAF controls | p Value | OR (95% CI)* | Q |

| 19 | rs34536443 (P1104A) | C/G | missense Pro >Ala | 0.023 | 0.026 | 2.28E-03 | 0.80 (0.69 to 0.92) | 0.13 |

| 19 | rs35018800 (A928V) | A/G | missense Ala >Val | 0.004 | 0.008 | 1.27E-03 | 0.59 (0.42 to 0.81) | 0.34 |

| 19 | rs12720356 (I684S) | C/A | missense Ile >Ser | 0.067 | 0.078 | 2.63E-05 | 0.83 (0.78 to 0.91) | 0.27 |

| 19 | rs2304256 (V362F) | A/C | missense Val >Phe | 0.246 | 0.279 | 3.08E-13 | 0.83 (0.79 to 0.87) | 0.69 |

OR for the minor allele.

Chr, chromosome; MAF, minor allele frequency; Q, heterogeneity value; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; SSc, systemic sclerosis.

Dependence analyses

We then assessed the independence of associations by conditional logistic regression analyses. Although pairwise conditioning results were not conclusive (table 2), the V362F genome-wide significance association was lost when adding the allelic dosage for rs3453644, rs35018800 and rs12720356 as covariates ( pcond=0.270) (table 3), supporting that the TYK2 V362F association was dependent on the three rare and low-frequency missense variants. Although A928V (rs35018800) seemed not to exert an effect on V362F (rs2304256) association, model fitting test showed that the regression model, including this rare variant as covariate had a significantly better likelihood than the model excluding it ( p=1.15×10−4). Allelic combination tests also confirmed that the V362F association was driven by the presence of the minor alleles of P1104A, A928V and I684S TYK2 variants, since no genome-wide significant p value was observed for the allelic model carrying only the minor allele of V362F (see online supplementary table S3).

Table 2.

Dependence analysis by pairwise conditioning of four TYK2 SNPs in the overall combined cohort (7103 patients with SSc and 12 220 controls)

| SNP | MAF cases/controls | Unconditioned p value | OR | *p Value: add to rs2304256 | OR† add to rs2304256 | *p Value: add to rs34536443 | OR† add to rs34536443 | *p Value: add to rs35018800 | OR† add to rs35018800 | *p Value: add to rs12720356 | OR† add to rs12720356 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs34536443 | 0.023/0.026 | 2.28E-03 | 0.80 | 0.02 | 0.84 | NA | NA | 1.51E-03 | 0.79 | 1.04E-03 | 0.78 |

| rs35018800 | 0.004/0.008 | 1.27E-03 | 0.59 | 9.56E-03 | 0.65 | 1.11E-03 | 0.57 | NA | NA | 1.20E-03 | 0.59 |

| rs12720356 | 0.067/0.078 | 2.63E-05 | 0.83 | 0.176 | 0.94 | 5.09E-06 | 0.82 | 2.22E-05 | 0.83 | NA | NA |

| rs2304256 | 0.246/0.279 | 3.08E-13 | 0.83 | NA | NA | 1.37E-05 | 0.89 | 4.75E-12 | 0.84 | 1.63E-07 | 0.86 |

Single locus test p value when SNP conditioned on rs2304256/rs34536443/rs35018800/rs12720356.

Single locus test OR when SNP conditioned on rs2304256/rs34536443/rs35018800/rs12720356.

MAF, minor allele frequency; NA, not applicable; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; SSc, systemic sclerosis.

Table 3.

Conditional logistic regression analysis of four TYK2 SNPs in the overall combined cohort (7103 patients with SSc and 12 220 controls)

| Conditioned to rs2304256, rs35018800, rs12720356 |

Conditioned to rs2304256, rs12720356, rs34536443 |

Conditioned to rs2304256, rs35018800, rs34536443 |

Conditioned to rs34536443, rs12720356 |

Conditioned to rs35018800, rs12720356, rs34536443 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | Unconditioned p value | OR | p Value | OR | p Value | OR | p Value | OR | p Value | OR | p Value | OR |

| rs34536443 | 2.28E-03 | 0.80 | 6.94E-04 | 0.76 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| rs35018800 | 1.27E-03 | 0.59 | NA | NA | 8.60E-04 | 0.56 | NA | NA | 9.39E-04 | 0.57 | NA | NA |

| rs12720356 | 2.63E-05 | 0.83 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 4.70E-04 | 0.84 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| rs2304256 | 3.08E-13 | 0.83 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.091 | 0.94 | 0.270 | 0.97 |

NA, not applicable; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; SSc, systemic sclerosis.

DISCUSSION

The overall analysis of our study reported genome-wide significance level of association for TYK2 with SSc, providing robust evidence for the implication of this new locus in SSc development.

The meta-analysis showed strong association for V362F common variant, whereas the rare and low-frequency variants— P1104A, A928V and I684S—remained with significant nominal association signals. Although our study was underpowered to detect associations at the genome-wide level of significance for these three missense variants, dependence analyses clearly supported that V362F association was a spurious signal, driven by P1104A, A928V and I684S. This effect is probably due to the high D values between V362F and the three rare and low-frequency variants.

Our findings are in accordance with the results reported by Diogo et al,6 which narrowed down TYK2 association to the three missense variants—P1104A, A928V and I684S—in RA and other autoimmune diseases through a fine-mapping strategy. The results are also consistent with the predictions of Polyphen-2 and SIFT tools, since common TYK2 missense variant, V362F, was predicted to be benign while P1104A, A928V and I684S were damaging mutations.30,31 In addition, the functional effect of P1104A and I684S variants (located in the kinase domains of the protein) has also been addressed by in vitro studies in primary T cells, B cells and fibroblasts. These studies showed that P1104A and I684S are catalytically impaired, leading to a reduced TYK2 activity and decreasing pro-inflammatory cytokines signalling, such as IL-6 or IL-12.32,33 Nevertheless, since the three TYK2 rare and low-frequency variants included in the present study were selected according to the detailed fine-mapping study performed by Diogo et al in a large RA study cohort, the genetic effect of additional independent rare and low-frequency TYK2 variants cannot be ruled out in SSc susceptibility.

Interestingly, several IL-12 pathway-related genes have been reported to be associated with SSc: IL12RB1 and IL12RB2 (both IL-12-receptor chains), IL12A ( p35 subunit of IL-12) and STAT4 (the transcription factor of the IL-12 signalling axis).3,4,8,9 Thus, the association of TYK2 with SSc reported in the present study adds another piece of evidence showing the crucial role of this IL pathway in SSc pathogenesis.

IL-12 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that induces type 1 helper T cells (Th1) and, in combination with interferon (IFN)-γ, antagonises type 2 helper T cells (Th2) differentiation.34 Serum levels of IL-12 are significantly increased in patients with SSc, and this overproduction has been associated with renal vascular damage.35 In addition, functional studies have suggested that Th1 responses may be crucial in mediating early inflammatory processes in SSc. As stated above, P1104A, A928V and I684S missense variants are damaging TYK2 mutations that ultimately lead to an impaired IL-12 signalling. This effect would be consistent with the protective effect observed for these variants and a lower SSc susceptibility. Thus, target therapies blocking this pathway could be an effective treatment for the disease, such as ustekinumab, an anti-IL-12/23 p40 monoclonal antibody currently approved for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis.36–38

Remarkably, pharmaceutical companies are setting their sight on JAK family as therapeutic targets for the treatment of autoimmune diseases, such as RA and type 1 diabetes, given its central role in the signalling pathways of a wide range of cytokines. Drug discovery research is focused on the development of specific JAK protein inhibitors, such as the recently approved JAK3 inhibitor, tofacitinib, for the treatment of RA.39 TYK2 inhibitors have also been described, although none of these drugs have yet made it to the clinical trials.40

In summary, the present study identified TYK2 as a novel susceptibility factor for SSc. Our results, together with previous findings, reinforce the crucial involvement of IL-12 signalling axis in the disease development; thus, this pathway might represent an attractive therapeutic target for the treatment of SSc.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Sofia Vargas, Sonia García and Gema Robledo for her excellent technical assistance and all the patients and control donors for their essential collaboration. We thank National DNA Bank Carlos III (University of Salamanca, Spain) who supplied part of the control DNA samples. We also would like to thank the following organisations: The EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research group (EUSTAR), the German Network of Systemic Sclerosis, The Scleroderma Foundation (USA) and RSA (Raynaud’s & Scleroderma Association).

Collaborators Spanish Scleroderma Group: Raquel Ríos and Jose Luis Callejas, Unidad de Enfermedades Sistémicas Autoinmunes, Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital Clínico Universitario San Cecilio, Granada; José Antonio Vargas Hitos, Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital Virgen de las Nieves, Granada; Rosa García Portales, Department of Rheumatology, Hospital Virgen de la Victoria, Málaga; María Teresa Camps, Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital Carlos Haya, Málaga; Antonio Fernández-Nebro, Department of Rheumatology, Hospital Carlos Haya, Málaga; María F González-Escribano, Department of Immunology, Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla; Francisco José García-Hernández and Mª Jesús Castillo, Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla; Mª Ángeles Aguirre and Inmaculada Gómez-Gracia, Department of Rheumatology, Hospital Reina Sofía/IMIBIC, Córdoba; Benjamín Fernández-Gutiérrez and Luis Rodríguez-Rodríguez, Department of Rheumatology, Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid; Esther Vicente, Department of Rheumatology, Hospital La Princesa, Madrid; José Luis Andreu and Mónica Fernández de Castro, Department of Rheumatology, Hospital Puerta de Hierro Majadahonda, Madrid; Francisco Javier López-Longo and Lina Martínez, Department of Rheumatology, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid; Vicente Fonollosa and Alfredo Guillén, Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital Valle de Hebrón, Barcelona; Iván Castellví, Department of Rheumatology, Santa Creu i Sant Pau University Hospital, Barcelona; Gerard Espinosa, Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital Clinic, Barcelona; Carlos Tolosa, Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital Parc Tauli, Sabadell; Anna Pros, Department of Rheumatology, Hospital Del Mar, Barcelona; Mónica Rodríguez Carballeira, Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital Universitari Mútua Terrasa, Barcelona; Francisco Javier Narváez, Department of Rheumatology, Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge, Barcelona; Manel Rubio Rivas, Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge, Barcelona; Vera Ortiz Santamaría, Department of Rheumatology, Hospital General de Granollers, Granollers; Ana Belén Madroñero, Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital General San Jorge, Huesca; Miguel Ángel González-Gay, Department of Rheumatology, Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, IFIMAV, Santander; Bernardino Díaz and Luis Trapiella, Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital Central de Asturias, Oviedo; Mayka Freire and Adrián Sousa, Unidad de Trombosis y Vasculitis, Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital Xeral-Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo, Vigo; María Victoria Egurbide, Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital Universitario Cruces, Barakaldo; Patricia Fanlo Mateo, Department of Internal Medicine Hospital Virgen del Camino, Pamplona; Luis Sáez-Comet, Unidad de Enfermedades Autoinmunes Sistémicas, Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza; Federico Díaz and Vanesa Hernández, Department of Rheumatology, Hospital Universitario de Canarias, Tenerife; Emma Beltrán, Department of Rheumatology, Hospital General Universitario de Valencia, Valencia; José Andrés Román-Ivorra and Elena Grau, Department of Rheumatology, Hospital Universitari i Politecnic La Fe, Valencia. Juan José Alegre Sancho, Department of Rheumatology, Hospital del Doctor Peset, Valencia. Francisco J. Blanco García and Natividad Oreiro, Department of Rheumatology, INIBIC-Hospital Universitario A Coruña, La Coruña.

Funding This work was supported by the following grants: JM was funded by GEN-FER from the Spanish Society of Rheumatology, SAF2009–11110 and SAF2012–34435 from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, and BIO-1395 from Junta de Andalucía. NO-C was funded by PI-0590–2010, from Consejería de Salud y Bienestar Social, Junta de Andalucía, Spain. EL-I was supported by Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte through the programme FPU. DC was supported by Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness through the programme FPI. LB-C was funded by the EU/EFPIA Innovative Medicines Initiative Joint Undertaking PRECISESADS (ref: 115565). TRDJR was funded by the VIDI laureate from the Dutch Association of Research (NWO) and Dutch Arthritis Foundation (National Reumafonds). Study on USA samples were supported by the Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), Centers of Research Translation (CORT) grant P50AR054144 (MDM), the NIH-NIAMS SSc Family Registry and DNA Repository (N01-AR-0-2251) (MDM), NIH-KL2RR024149-04 (SA), NIH-NCRR 3UL1RR024148, US NIH NIAID UO1 1U01AI09090, K23AR061436 (SA), Department of Defense PR1206877 (MDM) and NIH/NIAMS-RO1- AR055258 (MDM).

Footnotes

Competing interests None declared.

Ethics approval The local ethics committees.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gabrielli A, Avvedimento EV, Krieg T. Scleroderma. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1989–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Radstake TR, Gorlova O, Rueda B, et al. Genome-wide association study of systemic sclerosis identifies CD247 as a new susceptibility locus. Nat Genet 2010;42:426–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayes MD, Bossini-Castillo L, Gorlova O, et al. Immunochip analysis identifies multiple susceptibility Loci for systemic sclerosis. Am J Hum Genet 2014;94:47–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin JE, Bossini-Castillo L, Martin J. Unraveling the genetic component of systemic sclerosis. Hum Genet 2012;131:1023–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Assassi S, Radstake TR, Mayes MD, et al. Genetics of scleroderma: implications for personalized medicine? BMC Med 2013;11:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diogo D, Bastarache L, Liao KP, et al. TYK2 protein-coding variants protect against rheumatoid arthritis and autoimmunity, with no evidence of major pleiotropic effects on non-autoimmune complex traits. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0122271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parkes M, Cortes A, van Heel DA, et al. Genetic insights into common pathways and complex relationships among immune-mediated diseases. Nat Rev Genet 2013;14:661–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lopez-Isac E, Bossini-Castillo L, Guerra SG, et al. Identification of IL12RB1 as a novel systemic sclerosis susceptibility locus. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66:3521–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bossini-Castillo L, Martin JE, Broen J, et al. A GWAS follow-up study reveals the association of the IL12RB2 gene with systemic sclerosis in Caucasian populations. Hum Mol Genet 2012;21:926–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anon MC. Preliminary criteria for the classification of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). Subcommittee for scleroderma criteria of the American Rheumatism Association Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum 1980;23:581–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LeRoy EC, Medsger TA Jr. Criteria for the classification of early systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol 2001;28:1573–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LeRoy EC, Black C, Fleischmajer R, et al. Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis): classification, subsets and pathogenesis. J Rheumatol 1988;15:202–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howie BN, Donnelly P, Marchini J. A flexible and accurate genotype imputation method for the next generation of genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet 2009;5:e1000529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abecasis GR, Altshuler D, Auton A, et al. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature 2010;467:1061–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trynka G, Hunt KA, Bockett NA, et al. Dense genotyping identifies and localizes multiple common and rare variant association signals in celiac disease. Nat Genet 2011;43:1193–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eyre S, Bowes J, Diogo D, et al. High-density genetic mapping identifies new susceptibility loci for rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Genet 2012;44:1336–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper JD, Simmonds MJ, Walker NM, et al. Seven newly identified loci for autoimmune thyroid disease. Hum Mol Genet 2012;21:5202–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu JZ, Almarri MA, Gaffney DJ, et al. Dense fine-mapping study identifies new susceptibility loci for primary biliary cirrhosis. Nat Genet 2012;44:1137–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsoi LC, Spain SL, Knight J, et al. Identification of 15 new psoriasis susceptibility loci highlights the role of innate immunity. Nat Genet 2012;44:1341–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hinks A, Cobb J, Marion MC, et al. Dense genotyping of immune-related disease regions identifies 14 new susceptibility loci for juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Nat Genet 2013;45:664–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu JZ, Hov JR, Folseraas T, et al. Dense genotyping of immune-related disease regions identifies nine new risk loci for primary sclerosing cholangitis. Nat Genet 2013;45:670–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cortes A, Hadler J, Pointon JP, et al. Identification of multiple risk variants for ankylosing spondylitis through high-density genotyping of immune-related loci. Nat Genet 2013;45:730–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saruhan-Direskeneli G, Hughes T, Aksu K, et al. Identification of multiple genetic susceptibility loci in Takayasu arteritis. Am J Hum Genet 2013;93:298–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet 2007;81:559–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pruim RJ, Welch RP, Sanna S, et al. LocusZoom: regional visualization of genome-wide association scan results. Bioinformatics 2010;26:2336–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skol AD, Scott LJ, Abecasis GR, et al. Joint analysis is more efficient than replication-based analysis for two-stage genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet 2006;38:209–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cunninghame Graham DS, Morris DL, Bhangale TR, et al. Association of NCF2, IKZF1, IRF8, IFIH1, and TYK2 with systemic lupus erythematosus. PLoS Genet 2011;7:e1002341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hellquist A, Jarvinen TM, Koskenmies S, et al. Evidence for genetic association and interaction between the TYK2 and IRF5 genes in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 2009;36:1631–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sigurdsson S, Nordmark G, Goring HH, et al. Polymorphisms in the tyrosine kinase 2 and interferon regulatory factor 5 genes are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Hum Genet 2005;76:528–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods 2010;7:248–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar P, Henikoff S, Ng PC. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat Protoc 2009;4:1073–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Couturier N, Bucciarelli F, Nurtdinov RN, et al. Tyrosine kinase 2 variant influences T lymphocyte polarization and multiple sclerosis susceptibility. Brain 2011;134:693–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Z, Gakovic M, Ragimbeau J, et al. Two rare disease-associated Tyk2 variants are catalytically impaired but signaling competent. J Immunol 2013;190:2335–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vignali DA, Kuchroo VK. IL-12 family cytokines: immunological playmakers. Nat Immunol 2012;13:722–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sato S, Hanakawa H, Hasegawa M, et al. Levels of interleukin 12, a cytokine of type 1 helper T cells, are elevated in sera from patients with systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol 2000;27:2838–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leonardi CL, Kimball AB, Papp KA, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab, a human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriasis: 76-week results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (PHOENIX 1). Lancet 2008;371:1665–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Papp KA, Langley RG, Lebwohl M, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab, a human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriasis: 52-week results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (PHOENIX 2). Lancet 2008;371:1675–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Griffiths CE, Strober BE, van de Kerkhof P, et al. Comparison of ustekinumab and etanercept for moderate-to-severe psoriasis. N Engl J Med 2010;362:118–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garber K Pfizer’s first-in-class JAK inhibitor pricey for rheumatoid arthritis market. Nat Biotechnol 2013;31:3–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liang Y, Zhu Y, Xia Y, et al. Therapeutic potential of tyrosine kinase 2 in autoimmunity. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2014;18:571–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.