The gastrointestinal (GI) tract and liver represent common target organs of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).1 A recent meta-analysis showed that 17.6% of patients with COVID-19 had gastrointestinal symptoms.2 Digestive system involvement is associated with a poor disease course.3

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) are commonly used in patients with hypertension. A recent landmark study including 1128 patients with COVID-19 with hypertension showed that inpatient use of ACEI/ARB was associated with lower risk of mortality compared with ACEI/ARB nonusers.4 We aimed to determine the impact of ACEI/ARB use on the digestive system in patients with COVID-19 with hypertension.

Methods

A retrospective study investigating the clinical and virologic characteristics of COVID-19 between January 28, 2020, and April 8, 2020 was performed. All patients with COVID-19 cared for by the rescue medical team of the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University were recruited consecutively from the West Campus of Wuhan Union Hospital.

The primary outcome was to compare the rates of GI symptoms and abnormal liver function in COVID-19 hypertensive patients who used vs who did not use ACEI/ARB during the disease course. The secondary outcome was the prognosis of these patients, including complications, mortality, and length of hospital stay.

The definition of GI symptoms included abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting.3 The definition of abnormal liver function was alanine aminotransferase level of >40 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase level of >40 U/L, or total bilirubin level of >20 μmol/L.

The cumulative probabilities of GI involvement and abnormal liver function were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Statistical significance was set at P < .05.

Results

Participants

This study cohort included 204 consecutive patients with COVID-19. Among the 100 participants with hypertension, 31 were classified as the ACEI/ARB group, and the remaining 69 were classified as the non-ACEI/ARB group. The characteristics of the ACEI/ARB group vs the non-ACEI/ARB group on admission are provided in Supplementary Table 1. Comorbidities, including GI disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary heart disease, diabetes, and chronic renal disease, were comparable between the 2 groups (all P > .05). The rate of the critical/severe type was comparable between the ACEI/ARB group and the non-ACEI/ARB group (87.1% vs 87.0%; P > .05).

Compared to the ACEI/ARB group, the non-ACEI/ARB group had a higher prevalence of dyspnea and bilateral lung lesion at presentation. In terms of in-hospital treatment, the ACEI/ARB group had a higher percentage of using a beta-blocker (32.3% vs 4.3%; P < .001) and a lower percentage of systemic corticosteroid use (9.7% vs 37.7%; P < .01) than patients in the non-ACEI/ARB group (Supplementary Table 1).

Primary Outcome

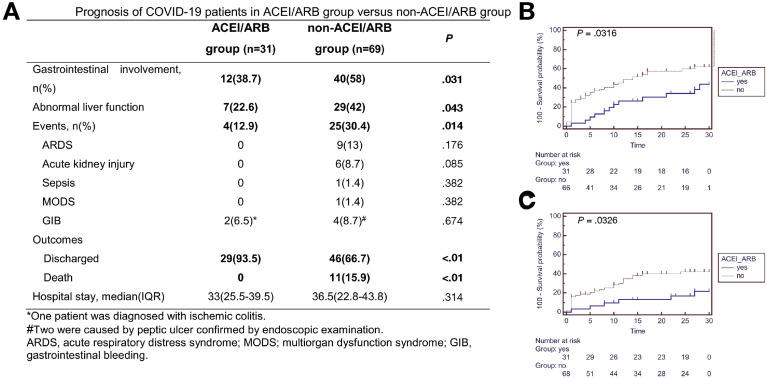

As shown in Figure 1 A, patients taking ACEI/ARB had a significantly lower risk of GI symptoms (38.7% vs 58%; P = .031) and abnormal liver function (22.6% vs 42%; P = .043) throughout the disease course. On admission, there was a trend toward, although not significantly, a lower rate of GI symptoms in the ACEI/ARB group compared to the non-ACEI/ARB group (12.9% [4/31] vs 29% [20/69]; P = .082). The spectrum of GI symptoms includes diarrhea (6.5% vs 14.5%), nausea and vomiting (9.7% vs 11.6%), and abdominal pain (2.9% vs 6.5%) in the ACEI/ARB group vs non-ACEI/ARB group, respectively.

Figure 1.

(A) Prognosis of patients with COVID-19 with hypertension in the ACEI/ARB and non-ACEI/ARB groups. (B, C) Kaplan-Meier curves for the cumulative probability of (B) gastrointestinal involvement and (C) abnormal liver function during 30-day follow-up in the ACEI/ARB or non-ACEI/ARB groups among 100 patients with COVID-19 with hypertension.

As shown in Figure 1 B and C, the cumulative rate of GI involvement was significantly lower in the ACEI/ARB group vs non-ACEI/ARB group (P = .032; hazard ratio, 1.95; 95% confidence interval, 1.11–3.42). Furthermore, the risk of abnormal liver function was also significantly lower in the ACEI/ARB group vs the non-ACEI/ARB group (P = .033; HR, 2.15; 95% CI, 1.07–4.27).

Secondary Outcome

As shown in Figure 1 A, during the follow-up period, 11 of the included 100 patients with hypertension died. The risk of all-cause mortality was significantly lower in the ACEI/ARB group vs non-ACEI/ARB group (0% [0/31] vs 15.9% [11/69]; P < .01).

Among patients using ACEI/ARB, only 2 (6.4%) patients used invasive ventilation; 2 (6.4%) patients had GI bleeding; and no patient had sepsis, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) or need for intensive care. All but 2 patients were discharged within a median of 33 (25.5–39.5) days of hospital stay. On the contrary, in the non-ACEI/ARB group, 11 (16.4%) patients were on mechanical ventilation (2 on noninvasive and 9 on invasive ventilation), 1 (1.5%) patient had sepsis, 1 (1.5%) patient had MODS, 4 (9%) patients had GI bleeding, and 3 (4.5%) patients needed intensive care. Forty-six (66.7%) patients were discharged with a median of 36.5 (22.8–43.8) days of hospital stay.

Discussion

The present study explored GI system involvement with the use of ACEI/ARB among patients with COVID-19 with hypertension. Our result showed that inpatient treatment with ACEI/ARB was associated with lower risk of GI system involvement compared with ACEI/ARB nonusers. Recently, it was reported that the serum level of angiotensin II is significantly elevated in patients with COVID-19 and exhibits a linear positive correlation to viral load and abnormal liver function.5 Activation of the RAS can cause widespread endothelial dysfunction and varying degrees of multiple organ (heart, kidney, lung, and digestive system) injuries. Thus, intake of ACEI/ARB might relieve organ damage, including GI and liver injury resulting from RAS activation.

Consistent with a previous study from Zhang et al,4 our study also showed that use of ACEI/ARB was associated with lower risk of all-cause mortality. Theoretically, ACEI/ARB could up-regulate ACE2 expression, which might increase severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 entry into cells.4 Alternatively, increased ACE2 activity could increase conversion of ACE2 to angiotensin, a peptide with potentially protective anti-inflammatory properties. Several hypotheses have been proposed to date regarding the net effect of ACEI/ARB on COVID-19 infections, without a firm conclusion.6 The recent statement from cardiovascular societies recommended the continuation of ACEI or ARB among patients with coexisting hypertension and COVID-19.7

This study has certain limitations. First, because of the small sample-size, we could not detect if there was a differential effect between ACEI and ARB. Second, the differences in proportions of patients using beta-blocker and systematic corticosteroids between the ACEI/ARB and non-ACEI/ARB groups might have had an unappreciated confounding effect.

Our study showed that inpatient treatment with ACEI/ARB was associated with lower risk of digestive system involvement and lower mortality compared with ACEI/ARB nonusers in patients with COVID-19 with hypertension. Large-scale prospective cohort studies and randomized controlled trials are needed to validate the preliminary findings of our study.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the members of the COVID-19 medical team of the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University who worked at the West Campus of Wuhan Union Hospital.

CRediT Authorship Contributions

Nian-Di Tan, MD (Conceptualization: Equal; Data curation: Lead; Formal analysis: Lead); Yun Qiu, MD (Conceptualization: Equal; Data curation: Equal; Formal analysis: Equal; Writing – original draft: Equal); Xiang-Bin Xing, MD (Formal analysis: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal); Subrata Ghosh, MD (Supervision: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Equal); Min-Hu Chen, MD (Conceptualization: Equal; Supervision: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal); Ren Mao, MD (Conceptualization: Lead; Supervision: Lead; Writing – review & editing: Lead).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authorship.

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Gastroenterology at www.gastrojournal.org, and at https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.034.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients With COVID-19 With Hypertension in the ACEI/ARB and Non-ACEI/ARB Groups

| Characteristics | ACEI/ARB group (n = 31) | Non-ACEI/ARB group (n = 69) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male: female) | 14:17 | 37:32 | .285 |

| Age, median (IQR) | 67 (62–70) | 67.5 (57–71) | .479 |

| Duration, median (IQR) | 10(7–16.5) | 12 (8.8–16) | .041 |

| Respiratory symptoms, n (%) | 20 (64.5) | 48 (69.6) | .359 |

| Fever | 24 (77.4) | 53 (76.8) | .850 |

| Cough/expectoration | 15 (48.4) | 37 (53.6) | .528 |

| Shortness of breath | 5 (16.1) | 24 (34.8) | .047 |

| Chest distress | 3 (9.7) | 5 (7.2) | .710 |

| GI symptoms, n (%) | 4 (12.9) | 20 (29) | .082 |

| Diarrhea | 2 (6.5) | 10 (14.5) | .211 |

| Vomiting | 3 (9.7) | 8 (11.6) | .738 |

| Abdominal pain | 2 (2.9) | 2 (6.5) | .436 |

| Comorbidities on admission, n (%) | |||

| Diabetes | 8 (25.8) | 20 (29) | .616 |

| GI comorbidities | 6 (19.4) | 17 (24.6) | .513 |

| Chronic renal diseases | 4 (12.9) | 5 (7.2) | .398 |

| Coronary heart disease | 5 (16.1) | 13 (18.8) | .697 |

| COPD | 2 (6.5) | 7 (10.1) | .524 |

| Tumor | 1(3.2) | 4(5.8) | .566 |

| Laboratory examination on admission, median (IQR) | |||

| AST | 27.5 (24-30.75) | 31.5 (22-49) | .103 |

| ALT | 34 (20-48) | 32 (18-59.7) | .409 |

| TBIL | 11.6 (7.8-13.9) | 11.4 (7.4-17.1) | .153 |

| CRP | 23.97 (4-43) | 24 (6.7-62.5) | .406 |

| Lymphocyte | 1.16 (0.8-1.6) | 1.01 (0.73-1.3) | .109 |

| D-dimer | 0.76 (0.26-2.39) | 0.96 (0.58-2.1) | .609 |

| Severity, n (%) | .613 | ||

| Mild | 0 (0) | 2 (2.9) | |

| Moderate | 4 (12.9) | 7 (10.1) | |

| Severe | 24 (77.4) | 38 (55.1) | |

| Critical | 3 (9.7) | 22 (31.9) | |

| In-hospital management, n (%) | |||

| Antiviral drug | 19 (61.3) | 52 (75.4) | .093 |

| Antibiotic drug | 17 (54.8) | 40 (58) | .650 |

| Antifungal medications | 0 | 4 (5.8) | .077 |

| Systemic corticosteroids | 3 (9.7) | 26 (37.7) | .003 |

| Lipid-lowering drug | 8 (25.8) | 10 (14.5) | .196 |

| CCB | 15 (48.4) | 24 (34.8) | .237 |

| Beta-blocker | 10 (32.3) | 3 (4.3) | <.001 |

| Alpha-blocker | 1 (3.2) | 1 (1.4) | .573 |

| ACEI | 4 (12.9) | 0 | |

| ARB | 27 (87.1) | 0 | |

| Renal replacement therapy | 1 (3.2) | 5 (7.2) | .416 |

| Noninvasive ventilation | 0 | 5 (7.2) | .048 |

| Invasive ventilation | 2 (6.5) | 9 (13) | .287 |

NOTE. Bold values are time from onset to admission, days, median (IQR).

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate transaminase; CCB, calcium channel blockers; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRP, C-reactive protein; IQR, Interquartile range; TBIL, total bilirubin.

References

- 1.Qi F. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020;526:135–140. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheung K.S., Hung I.F. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:81–95. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.03.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mao R., Qiu Y., He J.S., Tan J.Y., Li X.H. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:667–678. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30126-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang P., Zhu L., Cai J., Lei F., Qin J. Circ Res. 2020;126:1671–1681. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Y., Yang Y., Zhang C., Huang F. Sci China Life Sci. 2020;63:364–374. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1643-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rico-Mesa J. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2020;22:31. doi: 10.1007/s11886-020-01291-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bavishi C. JAMA Cardiol. 2020 Apr 3 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1282. [DOI] [Google Scholar]