Abstract

G6PD deficiency is a monogenic, X-linked genetic defect with a worldwide prevalence of around 400 million people and an overall prevalence of 8.5% in India. Hemolytic anemia is encountered in only a small proportion of patients with G6PD variants and is usually triggered by some exogenous agent. Although G6PD deficiency was reported in India more than 50 years ago, there are very few studies on molecular characterization and phenotypic correlation in G6PD deficient patients. We aimed to study the epidemiology and correlate the phenotypic expression with molecular genotypes in symptomatic G6PD deficient patients. All symptomatic hemolytic anaemia patients with a possible etiology of G6PD deficiency based on the clinical, hematological and biochemical parameters and reduced G6PD enzyme levels were included in this study. Molecular analysis of the G6PD gene was done by direct Sanger sequencing. From a total of 38 patients with hemolytic anemia suspected for G6PD deficiency, 24 patients had reduced G6PD enzyme levels and were included for the molecular analysis and mutations in the G6PD gene were identified in 21 of them (83.3%). The different mutations identified in our study include 6 patients with c.131C > G (G6PD Orissa), 3 patients with c.563C > T (G6PD Mediterranean), two patients with c.825G > T (G6PD Bangkok), one patient each with c.208T > C (G6PD Namouru), c.487G > A (G6PD Mahidol), c.949G > A (G6PD Kerala-Kalyan), c.100 G > A (G6PD Chatham), c.1178C > G (G6PD Nashville), c.1361 G > A (G6PD Andalus) and 4 patients with novel mutations (2 patients with c.1186C > T and 1 patient each with c.1288-2A > T and c.1372C > T. No disease causing genetic variants were identified in the other three cases. Co-inheritance of other red cell and hemoglobin disorders can modify the clinical phenotype of G6PD patients and the diagnostic accuracy can be improved by molecular characterization of the variant.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12288-019-01205-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: G6PD, Mutations, De novo, Lyonisation

Introduction

G6PD catalyses the conversion of glucose 6-phosphate (G6P) to 6-phosphogluconolactone in the pentose phosphate pathway, with concomitant reduction of NADP to NADPH. NADPH is required for the synthesis of glutathione (GSH), a key enzyme which protects the red blood cells from the oxygen radicals [1]. The gene encoding G6PD maps to the telomeric region of the long arm of X-chromosome (Xq28), close to the genes for hemophilia A, colour blindness and dyskeratosis congenita [2]. The G6PD gene consists of 13 exons (12 coding exons), 515 amino-acids and spans 15.63 kb in length (ENST00000393562.9).

G6PD deficiency is the most common human enzymopathy. It is often asymptomatic, however, it can cause neonatal jaundice, acute hemolytic episodes or present as chronic non-spherocytic hemolytic anemia [3]. Although the genetic abnormality is distributed worldwide, areas of high prevalence include Africa, the Middle East, South-East Asia and Southern Europe. At least 400 million people carry a G6PD deficiency gene, while the population-specific prevalence of G6PD deficiency in India is as high as 8.5% [4]. The vast majority of the patients with G6PD variants remain clinically asymptomatic throughout their lifetime [2]. They are, however prone to develop hemolysis when they are exposed to hemolytic stress like infections, drugs and ingestion of fava beans [5]. Around 186 genetic variants in the G6PD gene have been reported in the database, the majority of which are missense mutations with a single base substitution [6]. The clinical phenotype and the degree of hemolysis are related to the underlying genetic defect. While G6PD Mediterranean is the most common variant reported in the Middle East, variants like G6PD Orissa and G6PD Mahidol are commonly encountered in the Indian population [7, 8]. We aimed to study the epidemiology of symptomatic G6PD deficiency in patients from our centre and delineate the relationship between the underlying genetic defect and phenotypic expression in G6PD deficiency.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective study includes 38 consecutive patients who were evaluated for hemolytic anemia in the Department of Hematology, CMC Vellore. Among them, 24 patients had reduced G6PD enzyme levels (quantitative spectrophotometric assay using commercially procured G6PDH Randox reagent) who were subsequently screened for mutations in the G6PD gene. Clinical history, including presenting complaints, physical examination findings and biochemical investigation results were collected from the patient’s clinical records.

DNA Sequencing and Analysis

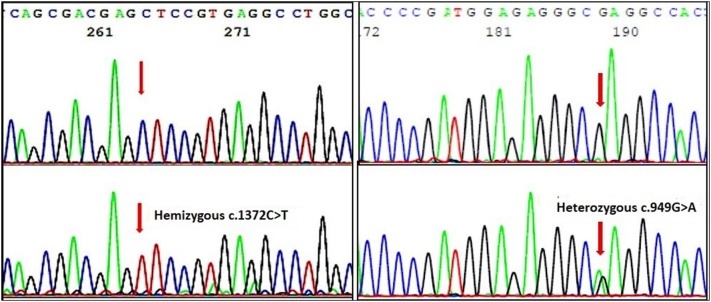

From the patients’ peripheral blood sample in EDTA tubes, Genomic DNA was extracted using a commercial kit (Gentra Puregene Blood kit, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Mutation analysis was performed with bidirectional Sanger sequencing using BigDye Terminator v3.1 chemistry and the analyses were carried out in ABI 3130 DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) (Fig. 2). Primers were designed to cover all the coding exons and the splice regions of the introns (20 bases on either side of the exons). A total of 10 primer pairs were used to simultaneously sequence the 12 coding exons and exon–intron junctions (supplement file S1). The sequences were read both manually and using bioinformatics software Geneious [9]. The reference sequence (ENSG00000160211) and transcript (ENST00000393562.9) were obtained from ENSEMBL (http://asia.ensembl.org/). Mutations identified were compared with the Leiden Open Variation Database for G6PD (https://databases.lovd.nl/shared/genes/G6PD). Designation of the mutations was done based on the guidelines given by the human genome variation society (http://www.hgvs.org/mutnomen/).

Fig. 2.

Representative electropherograms showing some of the mutations identified in our study. Forward sequences showing b hemizygous c.1372 C > T and d heterozygous c.949 G > A (G6PD Kerala Kalyan) mutations. Corresponding normal sequences are shown in (a) and (c)

Causality to Novel Mutations

For the novel mutations identified in the study, computational algorithms, namely SIFT, PROVEAN, PolyPhen2, PredictSNP2 and MutationTaster were used to predict their phenotypic effect [10–12]. Also, the protein sequences involving these mutation sites (for exonic mutations) were compared across different species to determine its functional importance. Based on the predictions from different scores and the degree of conservation of the protein sequence around the mutation site across species, the likely outcome (deleterious/benign) is reported for the novel mutations.

Results

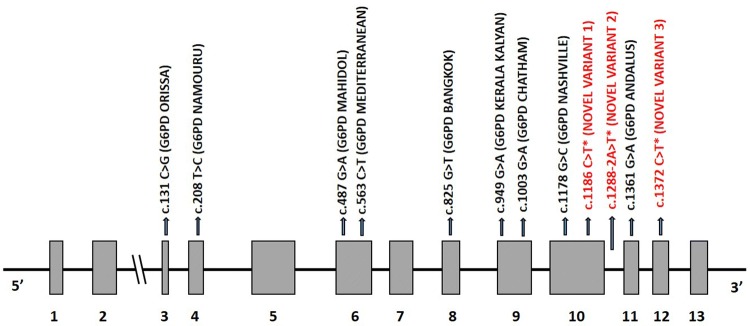

The study cohort had 24 patients (19 males and 5 females) with reduced G6PD enzyme levels (biological reference range > 6.5 U/g Hb) including 2 members from the same family. The median age of the patients at diagnosis was 3.5 years [range 7 months to 42 years]. All except three male patients presented in the first decade of life with hemolytic anemia while only one of the 5 female patients presented before the age of 10 years (Table 1 and supplement table S2). As this is a tertiary care referral hospital, there was a varied representation of patients from different populations (Table S2); however, majority of the patients were from Tamil Nadu, Kerala, West Bengal and Bangladesh. The clinical, biochemical and hematological findings in the study cohort are summarized in Table 1 (and Table S2). No mutation was detected in three patients (2 males and 1 female) who had borderline low G6PD enzyme levels. These three patients were later diagnosed with Parvovirus B19 induced pure red cell aplasia, hereditary spherocytosis and autoimmune hemolytic anemia respectively (Table 1). Patients with G6PD mutations had reduced Hb (Mean 6.7 gm/dL. Range 2.8–11.2 g/dL), increased reticulocyte count (Mean 8.82%. Range 1.33–16.68%) and LDH (Mean 2297.2 gm/dL. Range 340–7156 gm/dL) along with hyperbilirubinemia (Mean 4.81 gm/dL. Range 0.2–20.3 gm/dL) which was predominantly indirect. The various mutations identified in the study are summarized in Table 2, Fig. 1 and the representative electropherograms are shown in Fig. 2. G6PD Orissa was the most common mutation identified in six patients from five different families. We identified three novel variants in our study namely c.1186C > T, c.1288-2A > T and c.1372C > T. The variants identified in this study including the three novel variants have been uploaded in the Leiden Open Variation Database for G6PD https://databases.lovd.nl/shared/genes/G6PD. (We did not upload the common variants in our population like G6PD Orissa, G6PD Kerala-Kalyan and G6PD Mediterranean in the database).

Table 1.

Clinical and laboratory parameters in the study cohort

| S.No. | Age (in years) At diagnosis | Sex | Hb (g/dL) | Retic count (%) | G6PD Values$ (U/g Hb) | LDH (U/L) | History of Hematuria | Coexisting clinical condition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1* | 6 | Male | 7.6 | 16.68 | 1.1 | 3900 | Present | None |

| 2* | 2 | Male | TX | TX | 3.0 | 942 | Present | None |

| 3* | 1 | Male | 7.9 | 16.25 | < 0.2 | 7156 | NA | None |

| 4 | 3 | Female | 5 | NA | 5.1 | 5620 | Present | Cold Agglutinin Disease |

| 5 | 16 | Male | 8.9 | 3.53 | < 2.0 | 340 | Present | Beta Thalassemia Trait |

| 6 | 10 | Female | 11.2 | NA | < 2.1 | NA | Absent | Beta Thalassemia Trait |

| 7 | 1.5 | Male | 3.5 | NA | 1.7 | 2221 | NA | None |

| 8 | 0.8 | Male | 5.3 | 12 | < 2.1 | 752 | NA | Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia |

| 9 | 2 | Male | 3.7 | NA | < 2.1 | NA | Present | None |

| 10 | 0.8 | Male | 5.6 | 12.9 | < 2.1 | 648 | NA | Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia |

| 11 | 2 | Male | 2.8 | NA | 4.7 | NA | Present | Chemical Ingestion (Naphthalene Balls) |

| 12 | 29 | Female | 10.1 | 1.33 | < 2.1 | 650 | NA | Iron Deficiency Anemia + Ectopic gestation |

| 13 | 7 | Male | TX | 10.79 | NA | TX | Present | None |

| 14 | 2 | Male | 8.9 | 4.16 | < 2.1 | 743 | NA | Homozygous Sickle Cell Disease |

| 15 | 3 | Male | NA | NA | < 2.1 | NA | NA | NA |

| 16 | 13 | Female | NA | NA | < 2.1 | NA | NA | NA |

| 17 | 4 | Male | NA | NA | 0.5 | NA | Absent | Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia |

| 18* | 10 | Male | 8 | NA | 0.3 | NA | Absent | None |

| 19 | 42 | Male | NA | NA | 0.23 | NA | NA | Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia |

| 20 | 6 | Male | NA | NA | 1.3 | NA | NA | None |

| 21 | 18 | Male | 10.7 | NA | 0.6 | NA | NA | None |

| 22# | 8 | Male | 9.2 | 0.16 | 6.3 | 2614 | NA | Parvo virus B19 induced pure red cell aplasia |

| 23# | 0.6 | Male | 6.1 | 8.86 | 5.5 | 1142 | Absent | Hereditary spherocytosis |

| 24# | 23 | Female | 5.4 | 13.59 | 5.8 | 1085 | Present | Autoimmune hemolytic anemia |

*Patients with Novel variants

#Patients negative for G6PD mutations

$Biological Reference Range for G6PD is > 6.5 U/g Hb. TX transfused recently

NA not available, Hb Haemoglobin, LDH lactate dehydrogenase. Patients 1 and 3 were from the same family

Table 2.

Summary of the different G6PD mutations identified in our study

| S. No | Mutation | Exon/Intron number | HGVS nomenclature* | Amino acid change | Mutation Class(17) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | G6PD Orissa | Exon 3 | c.131C > G | p.Ala44Gly | Class III |

| 2 | G6PD Namouru | Exon 4 | c.208T > C | p.Tyr70His | Class II |

| 3 | G6PD Mahidol | Exon 6 | c.487G > A | p.Gly163Ser | Class III |

| 4 | G6PD Mediterranean | Exon 6 | c.563C > T | p.Ser188Phe | Class II |

| 5 | G6PD Bangkok | Exon 8 | c.825G > T | p.Lys275Asn | Class I |

| 6 | G6PD Kerala-Kalyan | Exon 9 | c.949G > A | p.Glu317Lys | Class III |

| 7 | G6PD Chatham | Exon 9 | c.1003G > A | p.Ala335Thr | Class II |

| 8 | G6PD Nashville | Exon 10 | c.1178C > G | p.Arg363His | Class I |

| 9 | Novel variant 1 | Exon10 | c.1186C > T | p.Pro396Ala | Class I |

| 10 | Novel variant 2 | Intron 10 | c.1288-2A > T | Splice variant | Not known |

| 11 | G6PD Andalus | Exon 11 | c.1361G > A | p.Arg454is | Class II |

| 12 | Novel variant 3 | Exon 12 | c.1372C > T | p.Leu458Phe | Class III |

*The variants are named in accordance with the reference transcript ENST00000393562.9 (http://asia.ensembl.org/). The variants have been uploaded in the Leiden Open Variation Database for G6PD https://databases.lovd.nl/shared/genes/G6PD

Fig. 1.

Structure of G6PD gene (Ensembl transcript ID: ENST00000393562.9 which has 13 exons coding for 515 amino acids) showing the spectrum of G6PD mutations identified in our study. *Novel variants

Interestingly, we had four female patients with G6PD mutations—two homozygous and two heterozygous variants. Both the female patients with homozygous variants had G6PD enzyme levels less than the Limit of Detection (LOD), presented with mild anemia (Hb 10.1 gm/dL and 11.2 gm/dL) and had no history of hematuria, organomegaly or transfusions in the past (Table 1). On the other hand, one female patient with heterozygous variant (c.949G > A) had a higher G6PD (5.1 U/gm Hb) and presented with severe anemia (Hb 5 gm/dL, severe hematuria, hepatosplenomegaly and history of transfusion. The severe phenotype correlated with the fact that she had cold agglutinin disease co-existing with G6PD deficiency (Table 1). The clinical details of the other female patient with a heterozygous variant (c.1451G > A) were not known.

Discussion

Hemolytic anemia due to G6PD deficiency occurs due to the interplay between intra-corpuscular enzyme deficiency and an extra-corpuscular cause which triggers hemolysis [2]. The common inducers of hemolysis include fava beans, infections and drugs [13]. Hematuria and jaundice are the most common clinical indications of hemolytic episodes. Hyperbilirubinemia and hemolysis resulting from G6PD deficiency are well documented in the newborn period, usually seen between days 2 and 3 [14, 15]. In our cohort, there were five patients who had neonatal hyperbilirubinemia: two patients from the same family with G6PD Bangkok, two patients with G6PD Mediterranean and one patient with G6PD Orissa. Close monitoring of serum bilirubin levels in infants known to be G6PD-deficient is warranted [16].

The World Health Organization (WHO) has classified G6PD variants based on the magnitude of the enzyme deficiency and the severity of hemolysis [17]. Mutations causing Class I variants associated with chronic hemolysis are clustered around exon 10, an area that governs the formation of the active G6PD dimer [18, 19]. G6PD genotype varies with the population. While G6PD Mediterranean is the commonest variant in the Middle East, G6PD Canton, G6PD Kaiping, and G6PD Gaohe are the common variants identified in the South East Asian population [20, 21]. The spectrum of mutations causing G6PD deficiency in Indian population is less clear with only two studies reporting the common genotypic variants in G6PD deficiency in India [7, 22]. G6PD Orissa was the commonest variant in our study identified in 6 patients from different families. We also identified three novel mutations in our study which were confirmed by various computational algorithms as described above. The first mutation, c.1186C > T, which we had reported earlier as a case report, resulted in chronic non-spherocytic anemia [Class I] in two members of the same family [23]. The second mutation, c.1288-2A > T was a splice site variant identified in a 11 year old Bengali child with G6PD level of 0.3 U/G Hb. While c.1288-2A > G [G6PD Zurich] has been reported earlier in the literature in the Swiss population, there is no record of c.1288-2A > T in the database [6]. The third novel mutation, c.1372 C > T was seen in a patient with G6PD level of 3.0 U/G Hb [Class III] who had a history of hematuria and occasional transfusion requirement.

Although the G6PD gene is located on the X chromosome, normal males and females have the same enzyme activity in their red cells. This is explained by Lyon’s hypothesis which states that one of two X chromosomes in each cell of the female embryo is inactivate and it persistently remains inactive throughout all subsequent cell divisions [24]. In fact, it was the studies by Beutler on females with G6PD deficiency which were used in the proof of the concept of Lyon hypothesis [25]. In our study, there were four female patients with class II/III G6PD variants. The patients with homozygous variants and markedly reduced G6PD enzyme levels had only mild anemia [Hb 10.1 gm/dL & 11.2 gm/dL] and were clinically asymptomatic while the female patient with heterozygous variant and G6PD enzyme level of 5.1 U/gm Hb presented with severe anemia, hematuria and hepatosplenomegaly with requirement of blood transfusions [Complete clinical details were not available for the other female patient as mentioned earlier]. The underlying genetic change determines the stability and half-life of the G6PD enzyme; shorter the half-life more severe the hemolysis [26].

This disparity in the clinical phenotype of the female G6PD deficient patients in our cohort highlights the fact that the clinical phenotype is not determined by the enzyme activity alone. Studies have shown that there could be a variation in the degree of hemolysis and anemia among family members with same G6PD variants, suggesting that additional factors [genetic or environmental] may influence the clinical outcome of G6PD deficiency [27, 28]. Co-inheritance of unrelated erythrocyte or hemoglobin disorders, like hereditary spherocytosis, thalassaemia, pyruvate kinase deficiency and congenital dyserythropoietic anaemia can influence the final clinical outcome in patients with G6PD deficiency [29–31]. Identification of the G6PD genetic variant can help in understanding the exact clinical phenotype in such cases. In our study, the severe phenotype in a female with heterozygous G6PD class III variant [Kerala Kalyan] and > 50% G6PD enzyme levels could be attributed to the co-existing cold agglutinin disease. Also, the biochemical assays to determine the G6PD enzyme levels is largely influenced by the percentage of circulating reticulocytes. Selective destruction of the older red cells along with the entry of numerous reticulocytes in the circulation can cause a transient, yet substantial increase in G6PD activity producing falsely normal enzyme values [32]. Although this variation is not as significant as seen with pyruvate kinase or hexokinase enzymes, a high reticulocyte count can still lead to elevated G6PD levels [33]. Molecular diagnosis can give a clearer picture in such cases where the enzyme level is disproportionate to the patient’s clinical phenotype. Although the prenatal diagnosis can be done in families with the more severe G6PD variants like G6PD Mediterranean, it’s role in routine patient care like beta thalassemia is controversial [34].

Conclusion

The wide spectrum of mutations in the G6PD gene, co-existence of other hemolytic disorders and the triggering etiology contribute to the heterogeneity in the pathophysiology of G6PD deficiency. Molecular characterization helps in better genotype–phenotype correlation and confirmation of the results where the enzyme levels are equivocal.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgement

The study was presented in the 58th Annual Conference of Indian Society of Hematology & Blood Transfusion (ISHBT) November 2017, Guwahati, India.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interest.

Human and Animal Rights

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee.

Informed Consent

This is a retrospective analysis using DNA extracted from EDTA blood sample that has been collected for routine molecular diagnostic procedures in patients suspected with G6PD deficiency in our institution. No additional sample was collected from any patient for this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Arun Kumar Arunachalam, Email: arun88@cmcvellore.ac.in.

S. Sumithra, Email: sumithra61@gmail.com

Madhavi Maddali, Email: madhavi.maddali@cmcvellore.ac.in.

N. A. Fouzia, Email: fouzian@cmcvellore.ac.in

Aby Abraham, Email: aby@cmcvellore.ac.in.

Biju George, Email: biju@cmcvellore.ac.in.

Eunice S. Edison, Email: eunice@cmcvellore.ac.in

References

- 1.Vulliamy T, Mason P, Luzzatto L. The molecular basis of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. Trends Genet. 1992;8(4):138–143. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(92)90372-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luzzatto L. Glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency: from genotype to phenotype. Haematologica. 2006;91(10):1303–1306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luzzatto L, Testa U. Human erythrocyte glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase: structure and function in normal and mutant subjects. Curr Top Hematol. 1978;1:1–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar P, Yadav U, Rai V. Prevalence of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency in India: an updated meta-analysis. Egypt J Med Hum Genet. 2016;17(3):295–302. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beutler E. G6PD: population genetics and clinical manifestations. Blood Rev. 1996;10(1):45–52. doi: 10.1016/s0268-960x(96)90019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minucci A, Moradkhani K, Hwang MJ, Zuppi C, Giardina B, Capoluongo E. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) mutations database: review of the “old” and update of the new mutations. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2012;48(3):154–165. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaeda JS, Chhotray GP, Ranjit MR, Bautista JM, Reddy PH, Stevens D, et al. A new glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase variant, G6PD Orissa (44 Ala → Gly), is the major polymorphic variant in tribal populations in India. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;57(6):1335–1341. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Jaouni SK, Jarullah J, Azhar E, Moradkhani K. Molecular characterization of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency in Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:436. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, et al. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(12):1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ng PC, Henikoff S. SIFT: predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(13):3812–3814. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7(4):248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwarz JM, Rödelsperger C, Schuelke M, Seelow D. MutationTaster evaluates disease-causing potential of sequence alterations. Nat Methods. 2010;7(8):575–576. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0810-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beutler E. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency: a historical perspective. Blood. 2008;111(1):16–24. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-077412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valaes T. Severe neonatal jaundice associated with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency: pathogenesis and global epidemiology. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 1994;394:58–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb13216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaplan M, Hammerman C. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency: a hidden risk for kernicterus. Semin Perinatol. 2004;28(5):356–364. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaplan M, Hammerman C, Beutler E. Hyperbilirubinaemia, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency and Gilbert syndrome. Eur J Pediatr. 2001;160(3):195. doi: 10.1007/pl00008422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.WHO Working Group Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. Bull World Health Organ. 1989;67(6):601–611. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehta A, Mason PJ, Vulliamy TJ. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2000;13(1):21–38. doi: 10.1053/beha.1999.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fiorelli G, Martinez di Montemuros F, Cappellini MD. Chronic non-spherocytic haemolytic disorders associated with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase variants. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2000;13(1):39–55. doi: 10.1053/beha.1999.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang W, Yu G, Liu P, Geng Q, Chen L, Lin Q, et al. Structure and function of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase-deficient variants in Chinese population. Hum Genet. 2006;119(5):463–478. doi: 10.1007/s00439-005-0126-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiu DT, Zuo L, Chao L, Chen E, Louie E, Lubin B, et al. Molecular characterization of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency in patients of Chinese descent and identification of new base substitutions in the human G6PD gene. Blood. 1993;81(8):2150–2154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohanty D, Mukherjee MB, Colah RB. Glucose–6–phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency in India. Indian J Pediatr. 2004;71(6):525–529. doi: 10.1007/BF02724295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edison ES, Melinkeri SR, Chandy M. A novel missense mutation in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase gene causing chronic nonspherocytic hemolytic anemia in an Indian family. Ann Hematol. 2006;85(12):879–880. doi: 10.1007/s00277-006-0156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lyon MF. Gene action in the X-chromosome of the mouse (Mus musculus L.) Nature. 1961;190:372–373. doi: 10.1038/190372a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beutler E, Yeh M, Fairbanks VF. The normal human female as a mosaic of x-chromosome activity: studies using the gene for g-6-pd-deficiency as a marker. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1962;48(1):9–16. doi: 10.1073/pnas.48.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chinevere TD, Murray CK, Grant E, Johnson GA, Duelm F, Hospenthal DR. Prevalence of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency in U.S. Army personnel. Military Medicine. 2006;171(9):905–907. doi: 10.7205/milmed.171.9.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Filosa S, Calabrò V, Vallone D, Poggi V, Mason P, Pagnini D, et al. Molecular basis of chronic non-spherocytic haemolytic anaemia: a new G6PD variant (393 Arg-His) with abnormal KmG6P and marked in vivo instability. Br J Haematol. 1992;80(1):111–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1992.tb06409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karadsheh NS, Awidi AS, Tarawneh MS. Two new glucose-6 phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) variants associated with hemolytic anemia: G6PD amman-1 and G6PD amman-2. Am J Hematol. 1986;22(2):185–192. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830220209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alfinito F, Calabro V, Cappellini MD, Fiorelli G, Filosa S, Iolascon A, et al. Glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency and red cell membrane defects: additive or synergistic interaction in producing chronic haemolytic anaemia. Br J Haematol. 1994;87(1):148–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1994.tb04885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ventura A, Panizon F, Soranzo MR, Veneziano G, Sansone G, Testa U, et al. Congenital dyserythropoietic anaemia type II associated with a new type of G6PD deficiency (G6PD Gabrovizza) Acta Haematol. 1984;71(4):227–234. doi: 10.1159/000206592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pyruvate kinase deficiency Association with G6PD deficiency. BMJ. 1992;305(6856):760–762. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6856.760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luzzatto L, Seneca E. G6PD deficiency: a classic example of pharmacogenetics with on-going clinical implications. Br J Haematol. 2014;164(4):469–480. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koralkova P, van Solinge WW, van Wijk R. Rare hereditary red blood cell enzymopathies associated with hemolytic anemia—pathophysiology, clinical aspects, and laboratory diagnosis. Int J Lab Hematol. 2014;36(3):388–397. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.12223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beutler E, Kuhl W, Fox M, Tabsh K, Crandall BF. Prenatal diagnosis of glucose-6-phosphate-dehydrogenase deficiency. AHA. 1992;87(1–2):103–104. doi: 10.1159/000204729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.