Abstract

Eltrombopag is a small molecule oral agonist of the thrombopoietin receptor. Initially used for improving thrombocytopenia in chronic immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), it was later found to be efficacious in various other etiologies of thrombocytopenia as well as inherited marrow failure syndromes. Lately, it has been used for thrombocytopenia and poor graft function after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) without any severe adverse events. Although prospective evidence of the efficacy is limited, there are increasing reports on the safety and efficacy with Eltrombopag in post HSCT thrombocytopenia and poor graft function. This provides an exciting opportunity for further research to evaluate both efficacy and cost-effectiveness of the use of Eltrombopag in this scenario. Here we review the current evidence on the indications for the use of Eltrombopag in the post allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant setting.

Keywords: Eltrombopag, Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, Thrombocytopenia, Poor graft function, Cytopenias

Background

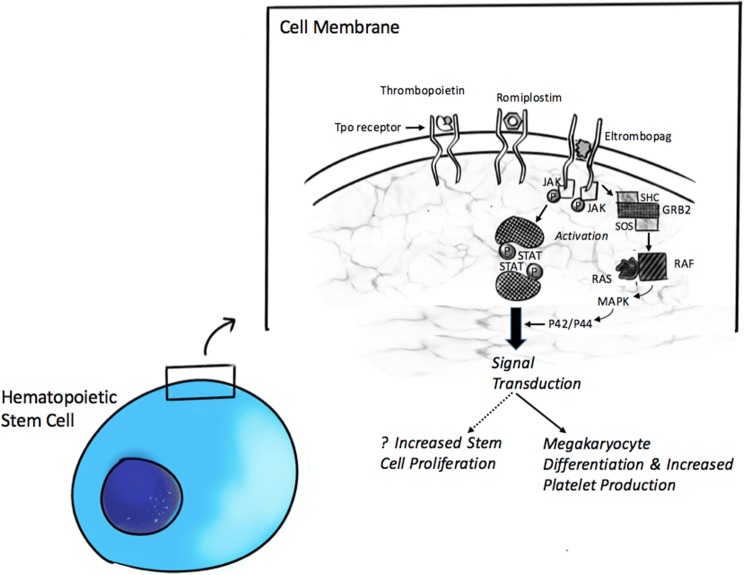

Eltrombopag (SB-497115) is a small molecule, non-peptide, oral agonist of the thrombopoietin receptor moiety (TpoR, also called CD110 or c-Mpl) [1, 2]. The drug interacts with the transmembrane domain of the receptor protein complex, initiating downstream signal transduction pathways involving both the Janus kinase/Signalling transducers and activators of transcription (JAK/STAT) and Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAP-K) signal transduction pathways (Fig. 1) [3]. These pathways ultimately result in involved cell differentiation and proliferation [4]. Pre-clinical studies, as well as healthy volunteer studies, showed an increase in platelet counts [5, 6]. This led in it being studied in chronic ITP [7] and thrombocytopenia in chronic hepatitis C related cirrhosis [8], ultimately resulting in its FDA approval in 2008 [9]. Eltrombopag was well tolerated with no reported dose-related severe adverse events [5]. Common side effects were upper respiratory infections, fever, musculoskeletal pain and elevation of liver function enzymes [1, 7].

Fig. 1.

Mechanism of action of Eltrombopag on hematopoietic stem cell. As shown, Eltrombopag binds to the thrombopoietin receptor's transmembrane domain (while TPO and Romiplostim bind to extracellular domains), activating signaling that leads to increased platelet production and possibly stem cell proliferation. GRB2 growth factor receptor–binding protein 2, JAK janus kinase, MAPK mitogen-activated protein kinase, P phosphorylation, RAF rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma kinase, RAS rat sarcoma GTPase, SHC Src homology collagen protein, STAT signal transducer and activator of transcription

Eltrombopag in Aplastic Anemia

The discovery of the efficacy of Eltrombopag in severe aplastic anemia was almost serendipitous. The phase 1/2 study on the efficacy of Eltrombopag in relapsed-refractory SAA, was initially designed (NCT00922883 www.clinicaltrials.gov) to test the safety and potential efficacy of Eltrombopag in patients with refractory thrombocytopenia for aplastic anemia. Interestingly, results of the trial showed a total of 44% of patients had a hematologic response of at least one lineage of cells with single-agent treatment [10].

The reason for the efficacy of Eltrombopag in bone marrow failure syndromes is still unclear and is postulated to be due to the following reasons.

The expression of c-Mpl in CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells and progenitor cells and stimulation of the same causing tri-lineage hematopoiesis [11]—acting as a stem cell stimulant.

c-Mpl gene knockout in mice was shown to reduce progenitor cells and induce pancytopenia [12].

Recombinant thrombopoietin was used in-vitro for expanding pools of hematopoietic stem cells in culture [11, 13].

Marrow failure eventually occurs in patients with congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia (with a hereditary mutation in the c-Mpl gene) [14, 15].

An immunomodulatory effect of Eltrombopag by preventing the release of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interferon (IFN-), increasing the population of T- regulatory cells and increasing secretion of transforming growth factor (TGF) [16, 17].

Overriding of the inhibitory effect of IFN- on c-Mpl receptors and thus delaying macrophage activation and inhibiting maturation of dendritic cells in SAA [18].

Eltrombopag also provides additional benefit in patients with relapsed refractory transfusion-dependent bone marrow failure through its action as an iron chelator along with intracellular iron mobilization [19, 20].

Eltrombopag was studied for frontline use in combination with conventional IST in non-transplant eligible SAA. An overall response rate of 94% was seen when all three drugs were used simultaneously [21] and this led to the FDA approval of Eltrombopag in frontline use in SAA along with standard immunosuppressive therapy in 2018 [22].

The stimulus of proliferation and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells by Eltrombopag lead to concerns of it inducing clonal evolution in patients with SAA. This concern was accentuated with early appearance (within 6 months) of cytogenetic abnormalities in some reports [23]. A recent review of data from two trials by Winkler et al. on Eltrombopag use in refractory SAA revealed concerning clonal evolution in 19% patients, mostly within 6 months of the start of Eltrombopag. They concluded that rapid cytogenetic evolution after initiation of Eltrombopag in a subset of patients with SAA is concerning as it may promote the expansion of dormant pre-existing clones of abnormal karyotype albeit without an increase in mutated allele fractions of myeloid cancer genes [24]. The role of Eltrombopag in increasing the risk of transformation to myeloid malignancies in aplastic anemia can only be addressed by a prospective randomized trial. The multicentre randomized control study (RACE study; NCT02099747) by the European group of Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) comparing horse anti-thymocyte globulin and cyclosporineA with or without Eltrombopag in SAA has finished accrual and will provide more definitive information on the efficacy and adverse effects of upfront use of Eltrombopag in combination with IST in SAA. The efficacy of Eltrombopag in improving cytopenias in aplastic anemia, where the bone marrow is hypo-cellular, has resulted in it being tried in the management of cytopenias post HSCT. A review of the mechanisms in aplastic anemia may help in understanding possible pathways by which Eltrombopag improves post-transplant cytopenias.

Eltrombopag in Thrombocytopenia After Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

Thrombocytopenia after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) can be due to many etiologies and may even be multifactorial and its incidence has been reported as high as 20% in various studies [25, 26]. For clinical purposes, thrombocytopenia after HSCT have been classified as.

Prolonged isolated thrombocytopenia defined as dependence on platelet transfusion ≥ 90 days after HSCT [26] and

Secondary failure of platelet recovery(SFPR) defined as decline in platelet counts to less than 20 × 109 L or requiring transfusion support after achieving a stable platelet engraftment [27].

Drugs, infections, the persistence of basic disease, sepsis, thrombotic microangiopathy, and liver dysfunction are the important causes to be ruled out in patients with thrombocytopenia after HSCT [27, 28]. Once these secondary causes are ruled out, immune thrombocytopenia and poor graft function are the two important reasons for thrombocytopenia after HSCT. Steroids and intravenous immunoglobulins are the commonly tried remedies for thrombocytopenia in this setting.

Yamazaki et al. [29] postulated that prolonged isolated thrombocytopenia was associated both with an impaired platelet production as well as increased platelet turnover, while Zhang et al. [30] showed that patients with prolonged thrombocytopenia after HSCT had a significant reduction in ploidy and immaturity of megakaryocytes. These mechanisms provided an ideal pathophysiological setting for the use of Eltrombopag recruiting hematopoietic stem cells from quiescent state [31].

Reid et al. in 2012 reported 2 cases of prolonged isolated thrombocytopenia after allogeneic HSCT who responded to Eltrombopag (50 mg) with the recovery of platelet counts to transfusion independent levels, eventually permitting tapering and stopping the drug [32]. Both the patients had a decreased megakaryocyte population prior to starting the drug. A phase 1 clinical study used varying doses (up to 300 mg) of Eltrombopag from the day of stem cell infusion [33]. They had a median time to platelet engraftment of 15 days and showed that Eltrombopag was well tolerated with no dose-related serious adverse events. However, in this study 2 patients developed thrombotic manifestations (one event of pulmonary embolism and one of catheter-related thrombosis). Thrombotic manifestations were, however, not seen in any of the follow-up studies of Eltrombopag [10, 21]. In a cohort predominantly composed of patients undergoing autologous stem cell transplant, Raut et al. [34], demonstrated a 100% response to Eltrombopag (25–50 mg) in patients with primary isolated thrombocytopenia post HSCT. Tanaka et al. [35] followed this up with a single centre experience of 12 patients of isolated thrombocytopenia (PIT = 5; SFPR = 7) and showed that 8/12 (66.7%) patients became transfusion independent on Eltrombopag (12.5–50 mg). All 8 patients who responded remained transfusion independent after stopping drug after a median duration of 116 (range 49–273) days of treatment. The only prospective randomized trial, till date, on use of Eltrombopag in post HSCT thrombocytopenia was by Popat et al. [36] and showed an overall response of 36% in the Eltrombopag arm (50–150 mg) and a significant difference in the number of patients achieved platelet counts more than 50 × 108 L (21.4% vs. 0%). The largest retrospective series till date on the use of Eltrombopag in thrombocytopenia post-HSCT was presented by the Grupo Español De Trasplante Hematopoyético (GETH) in their multi-center study and showed a 72% overall response to thrombopoietin receptor agonists (Eltrombopag-59% [25–150 mg]; Romiplostim-41%) [37]. Eltrombopag could be successfully discontinued in 62% of patients, without loss of response. They also demonstrated a significantly prolonged time for platelet recovery (43 vs. 23 days; P– 0.018) in patients with decreased megakaryocytes prior to starting thrombopoietin receptor agonists. A recent publication from the University of Florida showed a 62% response of Eltrombopag (25–50 mg) in 13 patients of thrombocytopenia after HSCT without a significant difference between patients with adequate and inadequate megakaryocytes in baseline bone marrow [38]. Existing literature on the use of Eltrombopag in thrombocytopenia post-HSCT (including case reports, abstracts, and original articles) are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Existing literature on Eltrombopag in thrombocytopenia after hematopoeitic stem cell transplantation

| References | No. of patients (n) | Patient population | Median day of starting Eltrombopag | Median duration of treatment | Dose of Eltrombopag (mg) | Outcomes (%) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raut et al. [34] | 12 | PIT; 2 Allo HSCT, 10 Auto HSCT | D + 21 | 29 days | 25–50 | 100 | Eltrombopag more cost effective than transfusions |

| Tanaka et al. [35] | 12 | 5 PIT, 7 SFPR; All Allo HSCT | D + 168 | 116 days | 12.5–50 | 67 | No difference in response between PIT and SFPR |

| Popat et al. [36] | 42 | Auto HSCT and Allo HSCT | NA | NA | 50–150 | 36 | Prospective study; RCT; Not published |

| Bento et al. [37] | 86 | PIT and SFPR; Allo HSCT; Eltrombopag 59%; Romiplostim 41% | D + 127 | 62 | 25–150 | 72 | Decreased megs a/w longer platelet recovery |

| Mori et. al [51] | 19 | Auto HSCT and allo HSCT; PIT and SFPR | D + 57 | NA | 25–50 | 74 | 100% response in Auto HSCT; In Allo HSCT, no difference in response b/w adequate and inadequate megs |

| Wang et al. [52] | 17 | PIT and SFPR; Not isolated thrombocytopenia | NA | NA | NA | 41 | Abstract-unpublished |

| Yuan et al. [38] | 13 | PIT and SFPR; allo HSCT | D + 81 | NA | 25–50 | 62 | No difference in response b/w adequate and inadequate megs |

PIT prolonged isolated thrombocytopenia, Allo HSCT allogeneic hematopoietic bone marrow transplantation, Auto HSCT autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, SFPR secondary failure of platelet recovery, RCT randomized control trial, megs megakaryocytes, a/w associated with, b/w between

Eltrombopag in Poor Graft Function After Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

While lack of engraftment or primary graft failure is a rare complication of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (occurring in 2–3% cases) [39], persistent cytopenias after HSCT, termed poor graft function (PGF) may occur in as many as 20% of the patients [40]. The exact definition of PGF is not standardized, but a definition used across studies is persistent thrombocytopenia (platelet count ≤ 20 × 109 L) with neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count ≤ 0.5 × 109 L) and/or anemia (hemoglobin ≤ 70 g/L) for at least 3 consecutive days after day 28 of HSCT. This should be associated with hypoplastic–aplastic bone marrow and complete donor chimerism without concurrent graft versus host disease (GVHD) or disease relapse [41]. The etiopathogenesis of PGF is postulated to be due to an immune and inflammatory milieu triggered by one or more factors such as infection, sepsis, GVHD, viral reactivation, drug therapy and contributed by the degree of HLA mismatch, stem cell dose and intensity of conditioning [42, 43]. The treatment options for PGF which persists despite correction of the reversible causes are limited, with hematopoietic stem cell boost from the same donor being the only therapy of proven benefit [44]. However, the pathophysiology of PGF is quite similar to acquired bone marrow failure syndromes like aplastic anemia and this has opened up a possibility of use of Eltrombopag for the same.

The evidence for the use of Eltrombopag in PGF came initially in the form of isolated case reports. Dyba et al. [45] and Master et al. [46] both described one case each of Eltrombopag (50 mg) being successfully used for complete count recovery in poor graft function after allogeneic HSCT. Tang et al. [47] from China published their experience of Eltrombopag (50–75 mg) in 12 patients with poor graft function post HSCT. Eltrombopag was given for a median of 8 weeks and showed an overall response in 10/12 patients (83.3%) and complete resolution of counts in 8 patients in whom the responses were sustained even after tapering and stopping the drug. Marotta et al. [41] published their experience from Italy, of Eltrombopag treatment (50–150 mg) in 12 patients with PGF (including haploidentical HSCT). This study included prolonged isolated thrombocytopenia in their inclusion criteria for poor graft function and had an overall response of 58.3%(7/12) with complete resolution of counts in 50% (n = 6) patients. All patients who achieved complete resolution were able to taper and stop the drug.

The largest data till date on the use of Eltrombopag in haploidentical HSCT was from Fu et al. [48], where Eltrombopag (25–100 mg) was used in a cohort of patients post haploidentical HSCT (n = 38) for variety of indications [PIT(n = 8), SFPR (n = 15) and PGF (n = 15)]. They showed an overall response of 63.2% (n = 24) among all patients and a 60% overall response in PGF. Of the responders, 79% (n = 19) were able to taper and stop Eltrombopag. Multivariate analysis showed that the type of cytopenia (PIT, SFPR or PGF) did not predict response to Eltrombopag. However, the presence of adequate megakaryocytes in bone marrow prior to starting predicted the response. Existing literature on the use of Eltrombopag in poor graft function post-HSCT (including abstracts and original articles) are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Existing literature on Eltrombopag in poor graft function with or without isolated cytopenias after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

| References | No. of patients (n) | Patient population and characteristics | Median day of starting Eltrombopag | Median duration of treatment | Dose of Eltrombopag (mg) | Outcomes (%) | Comments/additional findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tang et al. [47] | 12 | PGF; ALL-4; AML-3; SAA-3 | D + 175 | 8 weeks | 25–50 | 83.3 | 66% sustained complete resolution after stopping drug |

| Milovic et al. [53] | 4 | PGF; AML-3; ALL-1 | D + 83 | NA | 12.5–50 | 75 | 50% had sustained complete resolution; 1 patient had skin toxicity; |

| Giammarco et al. [54] | 10 | PGF + Isolated cytopenia; AML-4; ALL-3; MDS-2 | D + 134 | 164 days | 50–150 | 100 | Patients also supported with G-CSF and EPO; |

| Marotta et al. [41] | 12 | PGF + PIT + SFPR; AML-5; ALL-1; MDS-2; SAA-1 | D + 79 | 107 days | 25–150 | 58.3 | 50% had sustained complete resolution; All patients MAC; 75% Haplo-identical patients |

| Fu et al. [48] | 38 | PGF + PIT + SFPR; AML-14; ALL-17; MDS-1; SAA-6 | D + 179 | 64 days | 25–50 | 63.2 | Adequate megs prior to treatment favours response |

PGF poor graft function, NA not available, ALL acute lymphoblastic leukemia, AML acute myeloid leukemia, MDS myelodysplastic syndrome, SAA severe aplastic anemia, G-CSF granulocyte colony stimulating factor, EPO erythropoietin, MAC myeloablative conditioning, PIT persistent isolated thrombocytopenia, SFPR secondary failure of platelet recovery, megs megakaryocytes, EBMT European group of blood and marrow transplantation

Summary and Future Directions

Eltrombopag, although designed as a stimulator for Tpo receptor in megakaryocytes, has subsequently been found to have tri-lineage hematopoietic stimulatory and immune-modulatory properties. Multiple studies have shown its safety in the post HSCT setting with adverse events limited to self-limiting rash and asymptomatic elevation of transaminases, not requiring discontinuation of the drug. The concerns of Eltrombopag inducing bone marrow fibrosis, arterial thrombosis or malignant clonal hematopoiesis has not been supported across various studies, with Will et al. demonstrating the safety of Eltrombopag on bone marrow cells in patients with AML/MDS [49]. The same was validated in the more recent ASPIRE trial [50]. The efficacy of Eltrombopag in post HSCT setting was also demonstrated across studies, both in post HSCT thrombocytopenia (ORR range 40–100%) and in poor graft function (ORR 60–100%) (Tables 1, 2). All the trials to date except one (Popat et al. [36]—unpublished) have retrospectively evaluated the efficacy of Eltrombopag for thrombocytopenia and poor graft function after HSCT.

The post-transplant period is complex with multiple complications including bacterial infections, viral reactivations, organ toxicities, immunosuppression, graft versus host disease, and drug toxicities. In the setting of all the above confounding factors, it may be impractical to design a prospective randomized control trial with adequate power to assess the response of Eltrombopag in thrombocytopenia and poor graft function. However, this provides an exciting opportunity in resource-constrained settings where a CD34+ augmented stem cell boost treatment for poor graft function post-HSCT may not be practical. Hence, the authors recommend prospective reporting of all cases, possibly as a collaborative multi-centre effort, in which Eltrombopag has been used for cytopenias post-HSCT, which would be needed to draw definitive conclusions about the efficacy of the drug in this setting. Ongoing prospective studies (registered on ClinicalTrials.gov) on use of Eltrombopag in post HSCT thrombocytopenia, will hopefully provide us with a definitive idea about the drug efficacy in this setting. The study from MD Anderson Centre Centre (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01000051) has completed recruitment, while prospective studies from Sochow University in China (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03437603), Lilly University in France (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03948529) and multicentre studies from Spain (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03718533) and Italy (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01791101) have not completed/started patient recruitment.

The only study to have compared the cost of the use of Eltrombopag against that of continued supportive care is from India. Raut et al. [34] used Eltrombopag in patients having thrombocytopenia post-HSCT (both autologous and allogeneic) and observed that the cost of the drug was less than the total cost of irradiated platelet transfusions and extended hospitalization. More literature is needed to evaluate the cost and efficacy of Eltrombopag when compared to alternatives in patients with thrombocytopenia or poor graft function post-HSCT. This is an important aspect for research in countries where predominant health care spending is from the individual rather than from insurance coverage or state-sponsored treatment.

Given the pathophysiological background for the increased efficacy of Eltrombopag, and the anecdotal evidence of efficacy and safety of Eltrombopag in retrospective studies, many centres are using the drug in the post-transplant setting. At our center, if a patient post-allogeneic HSCT has new-onset persistent cytopenias not related to infections, drugs, relapse, dropping chimerism or GVHD, we prefer to give a trial of Eltrombopag if there are no contraindications. The starting dose is 50 mg daily for a week, which is increased to 100–150 mg a day if there are no toxicities. If there is no response in 8 weeks, or if not tolerated, the drug is discontinued. During this period, arrangements for alternative therapies, like donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI) or second HSCT, to be initiated if there is a suboptimal response to Eltrombopag. Our limited experience shows that Eltrombopag in post HSCT cytopenias is well tolerated with promising efficacy (unpublished data).

The available data on the use of Eltrombopag is limited and authors are mindful of the publication bias where non-response to Eltrombopag is under-reported. It is important that more trials are needed and that centers should report outcomes on the use of Eltrombopag in post-transplant cytopenias, to draw definitive conclusions. In view of the reported tolerability, efficacy and potential cost-saving compared to alternative therapies, the use of Eltrombopag for thrombocytopenia and poor graft function post-HSCT needs consideration.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Dr. Jeeno Jayan MS for his contribution towards creating the Illustration associated with this manuscript.

Funding

There is no funding source to declare.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Erhardt J, Erickson-Miller CL, Tapley P. SB 497115-GR, a low molecular weight TPOR agonist, does not induce platelet activation or enhance agonist-induced platelet aggregation in vitro. Blood. 2004;104:3888. doi: 10.1182/blood.V104.11.3888.3888. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jenkins JM, Williams DF, Deng Y, Deng YF, Uhl J, Uhl JF, Kitchen V, Kitchen VF, Collins D, Collins DF, Erickson-Miller CL, et al. Phase 1 clinical study of Eltrombopag, an oral, nonpeptide thrombopoietin receptor agonist. Blood. 2007;109(11):4739–4741. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-057968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Imbach P, Crowther M. Thrombopoietin-receptor agonists for primary immune thrombocytopenia. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(8):734–741. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct1014202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalota A, Brennan K, Erickson-Miller CL, Danet G, Carroll M, Gewirtz AM. Effects of SB559457, a novel small molecule thrombopoietin receptor (TpoR) agonist, on human hematopoietic cell growth and differentiation. Blood. 2004;104:2913. doi: 10.1182/blood.V104.11.2913.2913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Provan D, Saleh M, Goodison S, Rafi R, Stone N, Hamilton JM, et al. The safety profile of Eltrombopag, a novel oral platelet growth factor, in thrombocytopenic patients and healthy subjects. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(18_suppl):18596. doi: 10.1200/jco.2006.24.18_suppl.18596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sellers T, Hart T, Semanik M, Murthy K. Pharmacology and safety of SB-497115-GR, an orally active small molecular weight TPO receptor agonist, in chimpanzees, rats and dogs. Blood. 2004;104:2063. doi: 10.1182/blood.V104.11.2063.2063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bussel JB, Cheng GF, Saleh MN, Saleh MF, Psaila B, Psaila BF, Kovaleva L, Kovaleva LF, Meddeb B, Meddeb BF, Kloczko J, et al. Eltrombopag for the treatment of chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(22):2237–2247. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McHutchison JG, Dusheiko GF, Shiffman ML, Shiffman MF, Rodriguez-Torres M, Rodriguez-Torres MF, Sigal S, Sigal SF, Bourliere M, Bourliere MF, Berg T, et al. Eltrombopag for thrombocytopenia in patients with cirrhosis associated with hepatitis C. New Engl J Med. 2007;357:2227–2236. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eltrombopag FDA approval Letter for Chronic ITP Reference ID 4162520 FDA.pdf

- 10.Olnes MJ, Scheinberg PF, Calvo KR, Calvo KF, Desmond R, Desmond RF, Tang Y, Tang YF, Dumitriu B, Dumitriu BF, Parikh AR, et al. Eltrombopag and improved hematopoiesis in refractory aplastic anemia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(1):11–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshihara H, Arai FF, Hosokawa K, Hosokawa KF, Hagiwara T, Hagiwara TF, Takubo K, Takubo KF, Nakamura Y, Nakamura YF, Gomei Y, et al. Thrombopoietin/MPL signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cell quiescence and interaction with the osteoblastic niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(6):685–697. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alexander WS, Roberts AF, Nicola NA, Nicola NF, Li R, Li RF, Metcalf D, Metcalf D. Deficiencies in progenitor cells of multiple hematopoietic lineages and defective megakaryocytopoiesis in mice lacking the thrombopoietic receptor c-Mpl. Blood. 1996;87(6):2162–2170. doi: 10.1182/blood.V87.6.2162.bloodjournal8762162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeigler FC, de Sauvage FF, Widmer HR, Widmer HF, Keller GA, Keller GF, Donahue C, Donahue CF, Schreiber RD, Schreiber RF, Malloy B, et al. In vitro megakaryocytopoietic and thrombopoietic activity of c-mpl ligand (TPO) on purified murine hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 1994;84(12):4045–4052. doi: 10.1182/blood.V84.12.4045.bloodjournal84124045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ballmaier M, Germeshausen MF, Krukemeier S, Krukemeier SF, Welte K, Welte K. Thrombopoietin is essential for the maintenance of normal hematopoiesis in humans: development of aplastic anemia in patients with congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;996:17–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb03228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tonelli R, Scardovi AF, Pession A, Pession AF, Strippoli P, Strippoli PF, Bonsi L, Bonsi LF, Vitale L, Vitale LF, Prete A, et al. Compound heterozygosity for two different amino-acid substitution mutations in the thrombopoietin receptor (c-mpl gene) in congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia (CAMT) Hum Genet. 2000;107(3):225–233. doi: 10.1007/s004390000357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bao W, Bussel JF, Heck S, Heck SF, He W, He WF, Karpoff M, Karpoff MF, Boulad N, Boulad NF, Yazdanbakhsh K, et al. Improved regulatory T-cell activity in patients with chronic immune thrombocytopenia treated with thrombopoietic agents. Blood. 2010;116(22):4639–4645. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-281717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schifferli A, Kuhne T. Thrombopoietin receptor agonists: a new immune modulatory strategy in immune thrombocytopenia? Semin Hematol. 2016;53(Suppl 1):S31–S34. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2016.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alvarado LJAO, Huntsman HD, Cheng H, Townsley DM, Winkler T, Feng X, et al. Eltrombopag maintains human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells under inflammatory conditions mediated by IFN-γ. Blood. 2019;133(19):2043–2055. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-11-884486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vlachodimitropoulou E, Chen YL, Garbowski M, Koonyosying P, Psaila B, Sola-Visner M, et al. Eltrombopag: a powerful chelator of cellular or extracellular iron(III) alone or combined with a second chelator. Blood. 2017;130(17):1923–1933. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-10-740241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao Z, Sun Q, Sokoll LJ, Streiff M, Cheng Z, Grasmeder S, et al. Eltrombopag mobilizes iron in patients with aplastic anemia. Blood. 2018;131:2399–2402. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-01-826784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Townsley DM, Scheinberg P, Winkler T, Desmond R, Dumitriu B, Rios O, et al. Eltrombopag added to standard immunosuppression for aplastic anemia. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(16):1540–1550. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1613878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.https://www.novartis.com/news/media-releases/fda-approves-novartis-drug-promacta-first-line-saa-and-grants-breakthrough-therapy-designation-additional-new-indication

- 23.Desmond R, Townsley DF, Dumitriu B, Dumitriu BF, Olnes MJ, Olnes MF, Scheinberg P, Scheinberg PF, Bevans M, Bevans MF, Parikh AR, et al. Eltrombopag restores trilineage hematopoiesis in refractory severe aplastic anemia that can be sustained on discontinuation of drug. Blood. 2014;123(12):1818–1825. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-10-534743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winkler T, Fan X, Cooper J, Desmond R, Young DJ, Townsley DM, et al. Treatment optimization and genomic outcomes in refractory severe aplastic anemia treated with eltrombopag. Blood. 2019;133(24):2575–2585. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019000478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akahoshi Y, Kanda J, Gomyo A, Hayakawa J, Komiya Y, Harada N, et al. Risk factors and impact of secondary failure of platelet recovery after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(9):1678–1683. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nash RA, Gooley TF, Davis C, Davis CF, Appelbaum FR, Appelbaum FR. The problem of thrombocytopenia after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Stem Cells. 1996;14(Suppl 1):261–273. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530140734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bruno B, Gooley TF, Sullivan KM, Sullivan KF, Davis C, Davis CF, Bensinger WI, Bensinger WF, Storb R, Storb RF, Nash RA, et al. Secondary failure of platelet recovery after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2001;7(3):154–162. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2001.v7.pm11302549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.First LF, Smith BR, Smith BF, Lipton J, Lipton JF, Nathan DG, Nathan DF, Parkman R, Parkman RF, Rappeport JM, Rappeport JM. Isolated thrombocytopenia after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation: existence of transient and chronic thrombocytopenic syndromes. Blood. 1985;65(2):368–374. doi: 10.1182/blood.V65.2.368.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamazaki R, Kuwana MF, Mori T, Mori TF, Okazaki Y, Okazaki YF, Kawakami Y, Kawakami YF, Ikeda Y, Ikeda YF, Okamoto S, et al. Prolonged thrombocytopenia after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: associations with impaired platelet production and increased platelet turnover. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38(5):377–384. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang X, Fu HF, Xu L, Xu LF, Liu D, Liu DF, Wang J, Wang JF, Liu K, Liu KF, Huang X, et al. Prolonged thrombocytopenia following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and its association with a reduction in ploidy and an immaturation of megakaryocytes. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17(2):274–280. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marsh JC, Mufti GJ. Eltrombopag: a stem cell cookie? Blood. 2014;123(12):1774–1775. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-02-553404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reid R, Bennett JF, Becker M, Becker MF, Chen Y, Chen YF, Milner L, Milner LF, Phillips GL, 2nd, Phillips GL, 2nd, Liesveld J, et al. Use of Eltrombopag, a thrombopoietin receptor agonist, in post-transplantation thrombocytopenia. Am J Hematol. 2012;87(7):743–745. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liesveld JL, Phillips GL, 2nd, Becker M, Becker MF, Constine LS, Constine LF, Friedberg J, Friedberg JF, Andolina JR, Andolina F, Jr, Milner LA, et al. A phase 1 trial of Eltrombopag in patients undergoing stem cell transplantation after total body irradiation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19(12):1745–1752. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raut SS, Shah SA, Sharanangat VV, Shah KM, Patel KA, Anand AS, et al. Safety and efficacy of Eltrombopag in post-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) thrombocytopenia. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2015;31(4):413–415. doi: 10.1007/s12288-014-0491-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanaka T, Inamoto Y, Yamashita T, Fuji S, Okinaka K, Kurosawa S, et al. Eltrombopag for treatment of thrombocytopenia after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(5):919–924. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Popat UR, Ray G, Bassett RL, Poon M-YC, Valdez BC, Konoplev S, et al. Eltrombopag for post-transplant thrombocytopenia: results of phase II randomized double blind placebo controlled trial. Blood. 2015;126(23):738. doi: 10.1182/blood.V126.23.738.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bento L, Bastida JM, García-Cadenas I, García-Torres E, Rivera D, Bosch A, et al. Thrombopoietin receptor agonists for severe thrombocytopenia after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: experience of a multicenter study from the Grupo Español De Trasplante Hematopoyético (GETH) Blood. 2018;132(Suppl 1):200. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yuan C, Boyd AM, Nelson J, Patel RD, Varela JC, Goldstein SC, et al. Eltrombopag for treating thrombocytopenia after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2019.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olsson R, Remberger MF, Schaffer M, Schaffer MF, Berggren DM, Berggren DF, Svahn BM, Svahn BF, Mattsson J, Mattsson JF, Ringden O, et al. Graft failure in the modern era of allogeneic hematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48(4):537–543. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee KH, Lee JF, Choi SJ, Choi SF, Lee JH, Lee JF, Kim S, Kim SF, Seol M, Seol MF, Lee YS, et al. Failure of trilineage blood cell reconstitution after initial neutrophil engraftment in patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation–frequency and outcomes. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;33(7):729–734. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marotta S, Marano L, Ricci P, Cacace F, Frieri C, Simeone L, et al. Eltrombopag for post-transplant cytopenias due to poor graft function. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2019 doi: 10.1038/s41409-019-0442-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davies SM, Kollman CF, Anasetti C, Anasetti CF, Antin JH, Antin JF, Gajewski J, Gajewski JF, Casper JT, Casper JF, Nademanee A, et al. Engraftment and survival after unrelated-donor bone marrow transplantation: a report from the national marrow donor program. Blood. 2000;96(13):4096–4102. doi: 10.1182/blood.V96.13.4096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dominietto A, Raiola AF, van Lint MT, van Lint MF, Lamparelli T, Lamparelli TF, Gualandi F, Gualandi FF, Berisso G, Berisso GF, Bregante S, et al. Factors influencing haematological recovery after allogeneic haemopoietic stem cell transplants: graft‐versus‐host disease, donor type, cytomegalovirus infections and cell dose. Br J Haematol. 2001;112(1):219–227. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stasia A, Ghiso A, Galaverna F, Raiola AM, Gualandi F, Luchetti S, et al. CD34 selected cells for the treatment of poor graft function after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20(9):1440–1443. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dyba J, Tinmouth A, Bredeson C, Matthews J, Allan DS. Eltrombopag after allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation in a case of poor graft function and systematic review of the literature. Transfus Med. 2016;26(3):202–207. doi: 10.1111/tme.12300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Master S, Dwary A, Mansour R, Mills GM, Koshy N. Use of Eltrombopag in improving poor graft function after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Case Rep Oncol. 2018;11(1):191–195. doi: 10.1159/000487229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tang C, Chen F, Kong D, Ma Q, Dai H, Yin J, et al. Successful treatment of secondary poor graft function post allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with eltrombopag. J Hematol Oncol. 2018;11(1):103. doi: 10.1186/s13045-018-0649-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fu H, Zhang X, Han T, Mo X, Wang Y, Chen H, et al. Eltrombopag is an effective and safe therapy for refractory thrombocytopenia after haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2019 doi: 10.1038/s41409-019-0435-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Will B, Kawahara M, Luciano JP, Bruns I, Parekh S, Erickson-Miller CL, et al. Effect of the nonpeptide thrombopoietin receptor agonist Eltrombopag on bone marrow cells from patients with acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood. 2009;114(18):3899. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-219493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mittelman M, Platzbecker U, Afanasyev B, Grosicki S, Wong RSM, Anagnostopoulos A, et al. Eltrombopag for advanced myelodysplastic syndromes or acute myeloid leukaemia and severe thrombocytopenia (ASPIRE): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2018;5(1):e34–e43. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(17)-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mori S, Patel RD, Boyd A, Simon S, Nelson J, Goldstein SC. Eltrombopag treatment for primary and secondary thrombocytopenia post allogeneic and autologous stem cell transplantation is effective and safe. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24(3):S343–S344. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.12.408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang TP, Alencar MC, Ramirez J, Oliva MV, Cisneros S, Jean P, et al. Clinical characteristics and response rates to Eltrombopag for primary and secondary thrombocytopenia after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HCT) Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25(3):S135–S136. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.12.423. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vera Milovic AR, Nonaka C, Martinez G, Drelichman G, Feldman L, Real J (2018) Treatment of poor graft function after allogeneic SCT with Eltrombopag. Bone marrow transplantation with a booster of CD34-selected cells infused without conditioning. In: The 44th annual meeting of the european society for blood and marrow transplantation: physicians poster sessions, p 309

- 54.Giammarco S, Sica S, Chiusolo P, Laurenti L, Sorá F, Martino M, et al. Eltrombopag for the treatment of late cytopenia following allogeneic stem cell transplants. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2019;54:144–619. doi: 10.1038/s41409-019-0559-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]